[145] Ladies and Gentlemen, it is my privilege to be the Chairman at Professor Jung’s lecture at this evening’s meeting. It was my privilege twenty-one years ago to meet Professor Jung when he came over to London to give a series of addresses,1 but there was then a very small group of psychologically minded physicians. I remember very well how after the meetings we used to go to a little restaurant in Soho and talk until we were turned out. Naturally we were trying to pump Professor Jung as hard as we could. “When I said goodbye to Professor Jung he said to me—he did not say it very seriously—”I think you are an extravert who has become an introvert.” Frankly, I have been brooding about that ever since!

[146] Now, ladies and gentlemen, just a word about last night. I think Professor Jung gave us a very good illustration of his views and of his work when he talked about the value of the telescope. A man with a telescope naturally can see a good deal more than anybody with unaided sight. That is exactly Professor Jung’s position. With his particular spectacles, with his very specialized research, he has acquired a knowledge, a vision of the depth of the human psyche, which for many of us is very difficult to grasp. Of course, it will be impossible for him in the space of a few lectures to give us more than a very short outline of the vision he has gained. Therefore, in my opinion anything which might seem blurred or dark is not a question of obscurantism, it is a question of spectacles. My own difficulty is that, with my muscles of accommodation already hardening, it might be impossible for me ever to see that vision clearly, even if for the moment Professor Jung could lend me his spectacles. But however this may be, I know that we are all thrilled with everything he can tell us, and we know how stimulating it is to our own thinking, especially in a domain where speculation is so easy and where proof is so difficult.

[147] Ladies and Gentlemen, I ought to have finished my lecture on the association tests yesterday, but I would have had to overstep my time. So you must pardon me for coming back to the same thing once more. It is not that I am particularly in love with the association tests. I use them only when I must, but they are really the foundation of certain conceptions. I told you last time about the characteristic disturbances, and I think it would be a good thing, perhaps, if I were briefly to sum up all there is to say about the results of the experiment, namely about the complexes.

[148] A complex is an agglomeration of associations—a sort of picture of a more or less complicated psychological nature—sometimes of traumatic character, sometimes simply of a painful and highly toned character. Everything that is highly toned is rather difficult to handle. If, for instance, something is very important to me, I begin to hesitate when I attempt to do it, and you have probably observed that when you ask me difficult questions I cannot answer them immediately because the subject is important and I have a long reaction time. I begin to stammer, and my memory does not supply the necessary material. Such disturbances are complex disturbances—even if what I say does not come from a personal complex of mine. It is simply an important affair, and whatever has an intense feeling-tone is difficult to handle because such contents are somehow associated with physiological reactions, with the processes of the heart, the tonus of the blood vessels, the condition of the intestines, the breathing, and the innervation of the skin. Whenever there is a high tonus it is just as if that particular complex had a body of its own, as if it were localized in my body to a certain extent, and that makes it unwieldy, because something that irritates my body cannot be easily pushed away because it has its roots in my body and begins to pull at my nerves. Something that has little tonus and little emotional value can be easily brushed aside because it has no roots. It is not adherent or adhesive.

[149] Ladies and Gentlemen, that leads me to something very important—the fact that a complex with its given tension or energy has the tendency to form a little personality of itself. It has a sort of body, a certain amount of its own physiology. It can upset the stomach. It upsets the breathing, it disturbs the heart—in short, it behaves like a partial personality. For instance, when you want to say or do something and unfortunately a complex interferes with this intention, then you say or do something different from what you intended. You are simply interrupted, and your best intention gets upset by the complex, exactly as if you had been interfered with by a human being or by circumstances from outside. Under those conditions we really are forced to speak of the tendencies of complexes to act as if they were characterized by a certain amount of will-power. When you speak of will-power you naturally ask about the ego. Where then is the ego that belongs to the will-power of the complexes? We know our own ego-complex, which is supposed to be in full possession of the body. It is not, but let us assume that it is a centre in full possession of the body, that there is a focus which we call the ego, and that the ego has a will and can do something with its components. The ego also is an agglomeration of highly toned contents, so that in principle there is no difference between the ego-complex and any other complex.

[150] Because complexes have a certain will-power, a sort of ego, we find that in a schizophrenic condition they emancipate themselves from conscious control to such an extent that they become visible and audible. They appear as visions, they speak in voices which are like the voices of definite people. This personification of complexes is not in itself necessarily a pathological condition. In dreams, for instance, our complexes often appear in a personified form. And one can train oneself to such an extent that they become visible or audible also in a waking condition. It is part of a certain yoga training to split up consciousness into its components, each of which appears as a specific personality. In the psychology of our unconscious there are typical figures that have a definite life of their own.2

[151] All this is explained by the fact that the so-called unity of consciousness is an illusion. It is really a wish-dream. We like to think that we are one; but we are not, most decidedly not. We are not really masters in our house. We like to believe in our will-power and in our energy and in what we can do; but when it comes to a real show-down we find that we can do it only to a certain extent, because we are hampered by those little devils the complexes. Complexes are autonomous groups of associations that have a tendency to move by themselves, to live their own life apart from our intentions. I hold that our personal unconscious, as well as the collective unconscious, consists of an indefinite, because unknown, number of complexes or fragmentary personalities.

[152] This idea explains a lot. It explains, for instance, the simple fact that a poet has the capacity to dramatize and personify his mental contents. When he creates a character on the stage, or in his poem or drama or novel, he thinks it is merely a product of his imagination; but that character in a certain secret way has made itself. Any novelist or writer will deny that these characters have a psychological meaning, but as a matter of fact you know as well as I do that they have one. Therefore you can read a writer’s mind when you study the characters he creates.

[153] The complexes, then, are partial or fragmentary personalities. When we speak of the ego-complex, we naturally assume that it has a consciousness, because the relationship of the various contents to the centre, in other words to the ego, is called consciousness. But we also have a grouping of contents about a centre, a sort of nucleus, in other complexes. So we may ask the question: Do complexes have a consciousness of their own? If you study spiritualism, you must admit that the so-called spirits manifested in automatic writing or through the voice of a medium do indeed have a sort of consciousness of their own. Therefore unprejudiced people are inclined to believe that the spirits are the ghosts of a deceased aunt or grandfather or something of the kind, just on account of the more or less distinct personality which can be traced in these manifestations. Of course, when we are dealing with a case of insanity we are less inclined to assume that we have to do with ghosts. We call it pathological then.

[154] So much about the complexes. I insist on that particular point of consciousness within complexes only because complexes play a large role in dream-analysis. You remember my diagram (Figure 4) showing the different spheres of the mind and the dark centre of the unconscious in the middle. The closer you approach that centre, the more you experience what Janet calls an abaissement du niveau mental: your conscious autonomy begins to disappear, and you get more and more under the fascination of unconscious contents. Conscious autonomy loses its tension and its energy, and that energy reappears in the increased activity of unconscious contents. You can observe this process in an extreme form when you carefully study a case of insanity. The fascination of unconscious contents gradually grows stronger and conscious control vanishes in proportion until finally the patient sinks into the unconscious altogether and becomes completely victimized by it. He is the victim of a new autonomous activity that does not start from his ego but starts from the dark sphere.

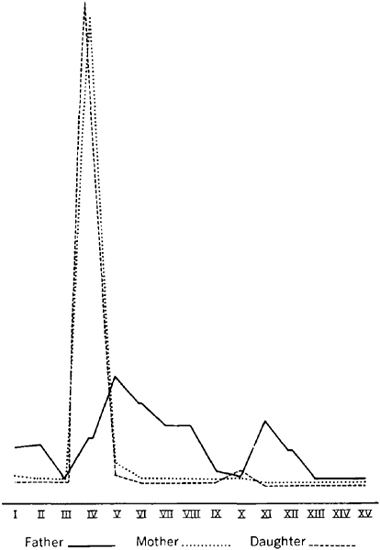

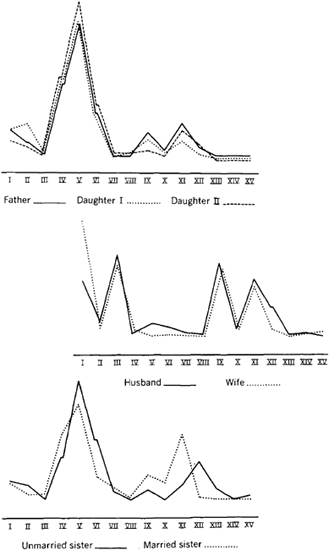

[155] In order to deal with the association test thoroughly, I must mention an entirely different experiment. You will forgive me if for the sake of economizing time I do not go into the details of the researches, but these diagrams (Figs. 8, 9, 10, 11) illustrate the results of very voluminous researches into families.3 They represent the quality of associations. For instance, the little summit in Figure 8 designated as number XI is a special class or category of association. The principle of classification is logical and linguistic. I am not going into this, and you will simply have to accept the fact that I have made fifteen categories into which I divide associations. We made tests with a great number of families, all for certain reasons uneducated people, and we found that the type of association and reaction is peculiarly parallel among certain members of the family; for instance, father and mother, or two brothers, or mother and child are almost identical in their type of reaction.

[156] I shall explain this by Figure 8. The dotted line (.....) represents the mother, the broken line (-----) her sixteen-year-old daughter, and the unbroken line (-) the father. This was a very unfortunate marriage. The father was an alcoholic and the mother was a very peculiar type. You see that the sixteen-year-old daughter follows her mother’s type closely. As much as thirty per cent of all associations are identical words. This is a striking case of participation, of mental contagion. If you think about this case you can draw certain conclusions. The mother was forty-five years old, married to an alcoholic. Her life was therefore a failure. Now the daughter has exactly the same reactions as the mother. If such a girl comes out into the world as though she were forty-five years old and married to an alcoholic, think what a mess she will get into! This participation explains why the daughter of an alcoholic who has had a hell of a youth will seek a man who is an alcoholic and marry him; and if by chance he should not be one, she will make him into one on account of that peculiar identity with one member of the family.

FIG. 8. Association Test of a Family

FIGS. 9–11. Association Tests of Families

[157] Figure 9 is a very striking case, too. The father, who was a widower, had two daughters who lived with him in complete identity. Of course, that also is most unnatural, because either he reacts like a girl or the two girls react like a man, even in the way they speak. The whole mental make-up is poisoned through the admixture of an alien element, because a young daughter is not in actual fact her father.

[158] Figure 10 is the case of a husband and wife. This diagram gives an optimistic tone to my very pessimistic demonstrations. You see there is perfect harmony here; but do not make the mistake of thinking that this harmony is a paradise, for these people will kick against each other after a while because they are just too harmonious. A very good harmony in a family based on participation soon leads to frantic attempts on the part of the spouses to kick loose from each other, to liberate themselves, and then they invent irritating topics of discussion in order to have a reason for feeling misunderstood. If you study the ordinary psychology of marriage, you discover that most of the troubles consist in this cunning invention of irritating topics which have absolutely no foundation.

[159] Figure 11 is also interesting. These two women are sisters living together; one is single and the other married. Their summit is found at number V. The wife in Figure 10 is the sister of these two women in Figure 11, and while most probably they were all of the same type originally, she married a man of another type. Their summit is at number III in Figure 10. The condition of identity or participation which is demonstrated in the association test can be substantiated by entirely different experiences, for instance, by graphology. The handwriting of many wives, particularly young wives, often resembles that of the husband. I do not know whether it is so in these days, but I assume that human nature remains very much the same. Occasionally it is the other way round because the so-called feeble sex has its strength sometimes.

[160] Ladies and Gentlemen, we are now going to step over the border into dreams. I do not want to give you any particular introduction to dream-analysis.4 I think the best way is just to show you how I proceed with a dream, and then it does not need much explanation of a theoretical kind, because you can see what are my underlying ideas. Of course, I make great use of dreams, because dreams are an objective source of information in psychotherapeutic treatment. When a doctor has a case, he can hardly refrain from having ideas about it. But the more one knows about cases, the more one should make an heroic effort not to know in order to give the patient a fair chance. I always try not to know and not to see. It is much better to say you are stupid, or play what is apparently a stupid role, in order to give the patient a chance to come out with his own material. That does not mean that you should hide altogether.

[161] This is a case of a man forty years old, a married man who has not been ill before. He looks quite all right; he is the director of a great public school, a very intelligent fellow who has studied an old-fashioned kind of psychology, Wundt psychology,5 that has nothing to do with details of human life but moves in the stratosphere of abstract ideas. Recently he had been badly troubled by neurotic symptoms. He suffered from a peculiar kind of vertigo that seized upon him from time to time, palpitation, nausea, and peculiar attacks of feebleness and a sort of exhaustion. This syndrome presents the picture of a sickness which is well known in Switzerland. It is mountain sickness, a malady to which people who are not used to great heights are easily subject when climbing. So I asked, “Is it not mountain sickness you are suffering from?” He said, “Yes, you are right. It feels exactly like mountain sickness.” I asked him if he had dreams, and he said that recently he had had three dreams.

[162] I do not like to analyse one dream alone, because a single dream can be interpreted arbitrarily. You can speculate anything about an isolated dream; but if you compare a series of, say, twenty or a hundred dreams, then you can see interesting things. You see the process that is going on in the unconscious from night to night, and the continuity of the unconscious psyche extending through day and night. Presumably we are dreaming all the time, although we are not aware of it by day because consciousness is much too clear. But at night, when there is that abaissement du niveau mental, the dreams can break through and become visible.

[163] In the first dream the patient finds himself in a small village in Switzerland. He is a very solemn black figure in a long coat; under his arm he carries several thick books. There is a group of young boys whom he recognizes as having been his classmates. They are looking at him and they say: “That fellow does not often make his appearance here.”

[164] In order to understand this dream you have to remember that the patient is in a very fine position and has had a very good scientific education. But he started really from the bottom and is a self-made man. His parents were very poor peasants, and he worked his way up to his present position. He is very ambitious and is filled with the hope that he will rise still higher. He is like a man who has climbed in one day from sea-level to a level of 6,000 feet, and there he sees peaks 12,000 feet high towering above him. He finds himself in the place from which one climbs these higher mountains, and because of this he forgets all about the fact that he has already climbed 6,000 feet and immediately he starts to attack the higher peaks. But as a matter of fact though he does not realize it he is tired from his climbing and quite incapable of going any further at this time. This lack of realization is the reason for his symptoms of mountain sickness. The dream brings home to him the actual psychological situation. The contrast of himself as the solemn figure in the long black coat with thick books under his arm appearing in his native village, and of the village boys remarking that he does not often appear there, means that he does not often remember where he came from. On the contrary he thinks of his future career and hopes to get a chair as professor. Therefore the dream puts him back into his early surroundings. He ought to realize how much he has achieved considering who he was originally and that there are natural limitations to human effort.

[165] The beginning of the second dream is a typical instance of the kind of dream that occurs when the conscious attitude is like his. He knows that he ought to go to an important conference, and he is taking his portfolio. But he notices that the hour is rather advanced and that the train will leave soon, and so he gets into that well-known state of haste and of fear of being too late. He tries to get his clothes together, his hat is nowhere, his coat is mislaid, and he runs about in search of them and shouts up and down the house, “Where are my things?” Finally he gets everything together, and runs out of the house only to find that he has forgotten his portfolio. He rushes back for it, and looking at his watch finds how late it is getting; then he runs to the station, but the road is quite soft so that it is like walking on a bog and his feet can hardly move any more. Pantingly he arrives at the station only to see that the train is just leaving. His attention is called to the railway track, and it looks like this:

FIG. 12. Dream of the Train

[166] He is at A, the tail-end of the train is already at B and the engine is at C. He watches the train, a long one, winding round the curve, and he thinks, “If only the engine-driver, when he reaches point D, has sufficient intelligence not to rush full steam ahead; for if he does, the long train behind him which will still be rounding the curve will be derailed.” Now the engine-driver arrives at D and he opens the steam throttle fully, the engine begins to pull, and the train rushes ahead. The dreamer sees the catastrophe coming, the train goes off the rails, and he shouts, and then he wakes up with the fear characteristic of nightmare.

[167] Whenever one has this kind of dream of being late, of a hundred obstacles interfering, it is exactly the same as when one is in such a situation in reality, when one is nervous about something. One is nervous because there is an unconscious resistance to the conscious intention. The most irritating thing is that consciously you want something very much, and an unseen devil is always working against it, and of course you are that devil too. You are working against this devil and do it in a nervous way and with nervous haste. In the case of this dreamer, that rushing ahead is also against his will. He does not want to leave home, yet he wants it very much, and all the resistance and difficulties in his way are his own doing. He is that engine-driver who thinks, “Now we are out of our trouble; we have a straight line ahead, and now we can rush along like anything.” The straight line beyond the curve would correspond to the peaks 12,000 feet high, and he thinks these peaks are accessible to him.

[168] Naturally, nobody seeing such a chance ahead would refrain from making the utmost use of it, so his reason says to him, “Why not go on, you have every chance in the world.” He does not see why something in him should work against it. But this dream gives him a warning that he should not be as stupid as this engine-driver who goes full steam ahead when the tail-end of the train is not yet out of the curve. That is what we always forget; we always forget that our consciousness is only a surface, our consciousness is the avant-garde of our psychological existence. Our head is only one end, but behind our consciousness is a long historical “tail” of hesitations and weaknesses and complexes and prejudices and inheritances, and we always make our reckoning without them. We always think we can make a straight line in spite of our shortcomings, but they will weigh very heavily and often we derail before we have reached our goal because we have neglected our tail-ends.

[169] I always say that our psychology has a long saurian’s tail behind it, namely the whole history of our family, of our nation, of Europe, and of the world in general. We are always human, and we should never forget that we carry the whole burden of being only human. If we were heads only we should be like little angels that have heads and wings, and of course they can do what they please because they are not hindered by a body that can walk only on the earth. I must not omit to point out, not necessarily to the patient but to myself, that this peculiar movement of the train is like a snake. Presently we shall see why.

[170] The next dream is the crucial dream, and I shall have to give certain explanations. In this dream we have to do with a peculiar animal which is half lizard and half crab. Before we go into the details of the dream, I want to make a few remarks about the method of working out the meaning of a dream. You know that there are many views and many misunderstandings as to the way in which you get at dreams.

[171] You know, for instance, what is understood by free association. This method is a very doubtful one as far as my experience goes. Free association means that you open yourself to any amount and kind of associations and they naturally lead to your complexes. But then, you see, I do not want to know the complexes of my patients. That is uninteresting to me. I want to know what the dreams have to say about complexes, not what the complexes are. I want to know what a man’s unconscious is doing with his complexes, I want to know what he is preparing himself for. That is what I read out of the dreams. If I wanted to apply the method of free association I would not need dreams. I could put up a signboard, for instance “Footpath to So-and-So,” and simply let people meditate on that and add free associations, and they would invariably arrive at their complexes. If you are riding in a Hungarian or Russian train and look at the strange signs in the strange language, you can associate all your complexes. You have only to let yourself go and you naturally drift into your complexes.

[172] I do not apply the method of free association because my goal is not to know the complexes; I want to know what the dream is. Therefore I handle the dream as if it were a text which I do not understand properly, say a Latin or a Greek or a Sanskrit text, where certain words are unknown to me or the text is fragmentary, and I merely apply the ordinary method any philologist would apply in reading such a text. My idea is that the dream does not conceal: we simply do not understand its language. For instance, if I quote to you a Latin or a Greek passage some of you will not understand it, but that is not because the text dissimulates or conceals; it is because you do not know Greek or Latin. Likewise, when a patient seems confused, it does not necessarily mean that he is confused, but that the doctor does not understand his material. The assumption that the dream wants to conceal is a mere anthropomorphic idea. No philologist would ever think that a difficult Sanskrit or cuneiform inscription conceals. There is a very wise word of the Talmud which says that the dream is its own interpretation. The dream is the whole thing, and if you think there is something behind it, or that the dream has concealed something, there is no question but that you simply do not understand it.

[173] Therefore, first of all, when you handle a dream you say, “I do not understand a word of that dream.” I always welcome that feeling of incompetence because then I know I shall put some good work into my attempt to understand the dream. What I do is this. I adopt the method of the philologist, which is far from being free association, and apply a logical principle which is called amplification. It is simply that of seeking the parallels. For instance, in the case of a very rare word which you have never come across before, you try to find parallel text passages, parallel applications perhaps, where that word also occurs, and then you try to put the formula you have established from the knowledge of other texts into the new text. If you make the new text a readable whole, you say, “Now we can read it.” That is how we learned to read hieroglyphics and cuneiform inscriptions and that is how we can read dreams.

[174] Now, how do I find the context? Here I simply follow the principle of the association experiment. Let us assume a man dreams about a simple sort of peasant’s house. Now, do I know what a simple peasant’s house conveys to that man’s mind? Of course not; how could I? Do I know what a simple peasant’s house means to him in general? Of course not. So I simply ask, “How does that thing appear to you?”—in other words, what is your context, what is the mental tissue in which that term “simple peasant’s house” is embedded? He will tell you something quite astonishing. For instance, somebody says “water.” Do I know what he means by “water”? Not at all. When I put that test word or a similar word to somebody, he will say “green.” Another one will say “H2O,” which is something quite different. Another one will say “quicksilver,” or “suicide.” In each case I know what tissue that word or image is embedded in. That is amplification. It is a well-known logical procedure which we apply here and which formulates exactly the technique of finding the context.

[175] Of course. I ought to mention here the merit of Freud, who brought up the whole question of dreams and who has enabled us to approach the problem of dreams at all. You know his idea is that a dream is a distorted representation of a secret incompatible wish which does not agree with the conscious attitude and therefore is censored, that is, distorted, in order to become unrecognizable to the conscious and yet in a way to show itself and live. Freud logically says then: Let us redress that whole distortion: now be natural, give up your distorted tendencies and let your associations flow freely, then we will come to your natural facts, namely, your complexes. This is an entirely different point of view from mine. Freud is seeking the complexes, I am not. That is just the difference. I am looking for what the unconscious is doing with the complexes, because that interests me very much more than the fact that people have complexes. We all have complexes: it is a highly banal and uninteresting fact. Even the incest complex which you can find anywhere if you look for it is terribly banal and therefore uninteresting. It is only interesting to know what people do with their complexes; that is the practical question which matters. Freud applies the method of free association and makes use of an entirely different logical principle, a principle which in logic is called reductio in primam figuram. reduction to the first figure. The reductio in primam figuram is a so-called syllogism, a complicated sequence of logical conclusions, whose characteristic is that you start from a perfectly reasonable statement, and, through surreptitious assumptions and insinuations, you gradually change the reasonable nature of your first simple or prime figure until you reach a complete distortion which is utterly unreasonable. That complete distortion, in Freud’s idea, characterizes the dream; the dream is a clever distortion that disguises the original figure, and you have only to undo the web in order to return to the first reasonable statement, which may be “I wish to commit this or that: I have such and such an incompatible wish.” We start, for instance, with a perfectly reasonable assumption, such as “No unreasonable being is free”—in other words, has free will. This is an example which is used in logic. It is a fairly reasonable statement. Now we come to the first fallacy, “Therefore, no free being is unreasonable.” You cannot quite agree because there is already a trick. Then you continue, “All human beings are free”—they all have free will. Now you triumphantly finish up, “Therefore no human being is unreasonable.” That is complete nonsense.

[176] Let us assume that the dream is such an utterly nonsensical statement. This is perfectly plausible because obviously the dream is something like a nonsensical statement; otherwise you could understand it. As a rule you cannot understand it; you hardly ever come across dreams which are clear from beginning to end. The ordinary dream seems absolute nonsense and therefore one depreciates it. Even primitives, who make a great fuss about dreams, say that ordinary dreams mean nothing. But there are “big” dreams; medicine men and chiefs have big dreams, but ordinary men have no dreams. They talk exactly like people in Europe. Now you are confronted with that dream-nonsense, and you say, “This nonsense must be an insinuating distortion or fallacy which derives from an originally reasonable statement.” You undo the whole thing and you apply the reductio in primam figuram and then you come to the initial undisturbed statement. So you see that the procedure of Freud’s dream-interpretation is perfectly logical, if you assume that the statement of the dream is really nonsensical.

[177] But do not forget when you make the statement that a thing is unreasonable that perhaps you do not understand because you are not God; on the contrary, you are a fallible human being with a very limited mind. When an insane patient tells me something, I may think: “What that fellow is talking about is all nonsense.” As a matter of fact, if I am scientific, I say “I do not understand,” but if I am unscientific, I say “That fellow is just crazy and I am intelligent.” This argumentation is the reason why men with somewhat unbalanced minds often like to become alienists. It is humanly understandable because it gives you a tremendous satisfaction, when you are not quite sure of yourself, to be able to say “Oh, the others are much worse.”

[178] But the question remains: Can we safely say that a dream is nonsense? Are we quite sure that we know? Are we sure that the dream is a distortion? Are you absolutely certain when you discover something quite against your expectation that it is a mere distortion? Nature commits no errors. Right and wrong are human categories. The natural process is just what it is and nothing else—it is not nonsense and it is not unreasonable. We do not understand: that is the fact. Since I am not God and since I am a man of very limited intellectual capacities, I had better assume that I do not understand dreams. With that assumption I reject the prejudiced view that the dream is a distortion, and I say that if I do not understand a dream, it is my mind which is distorted, I am not taking the right view of it.

[179] So I adopted the method which philologists apply to difficult texts, and I handle dreams in the same way. It is, of course, a bit more circumstantial and more difficult; but I can assure you that the results are far more interesting when you arrive at things that are human than when you apply a most dreadful monotonous interpretation. I hate to be bored. Above all we should avoid speculations and theories when we have to deal with such mysterious processes as dreams. We should never forget that for thousands of years very intelligent men of great knowledge and vast experience held very different views about them. It is only quite recently that we invented the theory that a dream is nothing. All other civilizations have had very different ideas about dreams.

[180] Now I will tell you the big dream of my patient: “I am in the country, in a simple peasant’s house, with an elderly, motherly peasant woman. I talk to her about a great journey I am planning: I am going to walk from Switzerland to Leipzig. She is enormously impressed, at which I am very pleased. At this moment I look through the window at a meadow where there are peasants gathering hay. Then the scene changes. In the background appears a monstrously big crab-lizard. It moves first to the left and then to the right so that I find myself standing in the angle between them as if in an open pair of scissors. Then I have a little rod or a wand in my hand, and I lightly touch the monster’s head with the rod and kill it. Then for a long time I stand there contemplating that monster.”

[181] Before I go into such a dream I always try to establish a sequence, because this dream has a history before and will have a history afterwards. It is part of the psychic tissue that is continuous, for we have no reason to assume that there is no continuity in the psychological processes, just as we have no reason to think that there is any gap in the processes of nature. Nature is a continuum, and so our psyche is very probably a continuum. This dream is just one flash or one observation of psychic continuity that became visible for a moment. As a continuity it is connected with the preceding dreams. In the previous dream we have already seen that peculiar snake-like movement of the train. This comparison is merely a hypothesis, but I have to establish such connections.

[182] After the train-dream the dreamer is back in the surroundings of his early childhood; he is with a motherly peasant woman—a slight allusion to the mother, as you notice. In the very first dream, he impresses the village boys by his magnificent appearance in the long coat of the Herr Professor. In this present dream too he impresses the harmless woman with his greatness and the greatness of his ambitious plan to walk to Leipzig—an allusion to his hope of getting a chair there. The monster crab-lizard is outside our empirical experience; it is obviously a creation of the unconscious. So much we can see without any particular effort.

[183] Now we come to the actual context. I ask him, “What are your associations to ‘simple peasant’s house’?” and to my enormous astonishment he says, “It is the lazar-house of St. Jacob near Basel.” This house was a very old leprosery, and the building still exists. The place is also famous for a big battle fought there in 1444 by the Swiss against the troops of the Duke of Burgundy. His army tried to break into Switzerland but was beaten back by the avant-garde of the Swiss army, a body of 1,300 men who fought the Burgundian army consisting of 30,000 men at the lazar-house of St. Jacob. The 1,300 Swiss fell to the very last man, but by their sacrifice they stopped the further advance of the enemy. The heroic death of these 1,300 men is a notable incident in Swiss history, and no Swiss is able to talk of it without patriotic feeling.

[184] Whenever the dreamer brings such a piece of information, you have to put it into the context of the dream. In this case it means that the dreamer is in a leprosery. The lazar-house is called “Siechenhaus,” sick-house, in German, the “sick” meaning the lepers. So he has, as it were, a revolting contagious disease; he is an outcast from human society, he is in the sick-house. And that sick-house is characterized, moreover, by that desperate fight which was a catastrophe for the 1,300 men and which was brought about by the fact that they did not obey orders. The avant-garde had strict instructions not to attack but to wait until the whole of the Swiss army had joined up with them. But as soon as they saw the enemy they could not hold back and, against the commands of their leaders, made a headlong rush and attacked, and of course they were all killed. Here again we come to the idea of this rushing ahead without establishing a connection with the bulk of the tail-end, and again the action is fatal. This gave me a rather uncanny feeling, and I thought, “Now what is the fellow after, what danger is he coming to?” The danger is not just his ambition, or that he wishes to be with the mother and commit incest, or something of the kind. You remember, the engine-driver is a foolish fellow too; he runs ahead in spite of the fact that the tail-end of the train is not yet out of the curve; he does not wait for it, but rushes along without thinking of the whole. That means that the dreamer has the tendency to rush ahead, not thinking of his tail; he behaves as if he were his head only, just as the avant-garde behaved as if it were the whole army, forgetting that it had to wait; and because it did not wait, every man was killed. This attitude of the patient is the reason for his symptoms of mountain sickness. He went too high, he is not prepared for the altitude, he forgets where he started from.

[185] You know perhaps the novel by Paul Bourget, L’Étape. Its motif is the problem that a man’s low origin always clings to him, and therefore there are very definite limitations to his climbing the social ladder. That is what the dream tries to remind the patient of. That house and that elderly peasant woman bring him back to his childhood. It looks, then, as if the woman might refer to the mother. But one must be careful with assumptions. His answer to my question about the woman was “That is my landlady.” His landlady is an elderly widow, uneducated and old-fashioned, living naturally in a milieu inferior to his. He is too high up, and he forgets that the next part of his invisible self is the family in himself. Because he is a very intellectual man, feeling is his inferior function. His feeling is not at all differentiated, and therefore it is still in the form of the landlady, and in trying to impose upon that landlady he tries to impose upon himself with his enormous plan to walk to Leipzig.

[186] Now what does he say about the trip to Leipzig? He says, “Oh, that is my ambition. I want to go far, I wish to get a Chair.” Here is the headlong rush, here is the foolish attempt, here is the mountain sickness; he wants to climb too high. This dream was before the war, and at that time to be a professor in Leipzig was something marvellous. His feeling was deeply repressed; therefore it does not have right values and is much too naïve. It is still the peasant woman; it is still identical with his own mother. There are many capable and intelligent men who have no differentiation of feeling, and therefore their feeling is still contaminated with the mother, is still in the mother, identical with the mother, and they have mothers’ feelings; they have wonderful feelings for babies, for the interiors of houses and nice rooms and for a very orderly home. It sometimes happens that these individuals, when they have turned forty, discover a masculine feeling and then there is trouble.

[187] The feelings of a man are so to speak a woman’s and appear as such in dreams. I designate this figure by the term anima, because she is the personification of the inferior functions which relate a man to the collective unconscious. The collective unconscious as a whole presents itself to a man in feminine form. To a woman it appears in masculine form, and then I call it the animus. I chose the term anima because it has always been used for that very same psychological fact. The anima as a personification of the collective unconscious occurs in dreams over and over again.6 I have made long statistics about the anima figure in dreams. In this way one establishes these figures empirically.

[188] When I ask my dreamer what he means when he says that the peasant woman is impressed by his plan, he answers, “Oh, well, that refers to my boasting. I like to boast before an inferior person to show who I am; when I am talking to uneducated people I like to put myself very much in the foreground. Unfortunately I have always to live in an inferior milieu.” When a man resents the inferiority of his milieu and feels that he is too good for his surroundings, it is because the inferiority of the milieu in himself is projected into the outer milieu and therefore he begins to mind those things which he should mind in himself. When he says, “I mind my inferior milieu,” he ought to say, “I mind the fact that my own inner milieu is below the mark.” He has no right values, he is inferior in his feeling-life. That is his problem.

[189] At this moment he looks out of the window and sees the peasants gathering hay. That, of course, again is a vision of something he has done in the past. It brings back to him memories of similar pictures and situations; it was in summer and it was pretty hard work to get up early in the morning to turn the hay during the day and gather it in the evening. Of course, it is the simple honest work of such folk. He forgets that only the decent simple work gets him somewhere and not a big mouth. He also asserts, which I must mention, that in his present home he has a picture on the wall of peasants gathering hay, and he says, “Oh, that is the origin of the picture in my dream.” It is as though he said, “The dream is nothing but a picture on the wall, it has no importance, I will pay no attention to it.” At that moment the scene changes. When the scene changes you can always safely conclude that a representation of an unconscious thought has come to a climax, and it becomes impossible to continue that motif.

[190] Now in the next part of the dream things are getting dark; the crab-lizard appears, apparently an enormous thing. I asked, “What about the crab, how on earth do you come to that?” He said, “That is a mythological monster which walks backwards. The crab walks backwards. I do not understand how I get to this thing—probably through some fairytale or something of that sort.” What he had mentioned before were all things which you could meet with in real life, things which do actually exist. But the crab is not a personal experience, it is an archetype. When an analyst has to deal with an archetype he may begin to think. In dealing with the personal unconscious you are not allowed to think too much and to add anything to the associations of the patient. Can you add something to the personality of somebody else? You are a personality yourself. The other individual has a life of his own and a mind of his own inasmuch as he is a person. But inasmuch as he is not a person, inasmuch as he is also myself, he has the same basic structure of mind, and there I can begin to think, I can associate for him. I can even provide him with the necessary context because he will have none, he does not know where that crab-lizard comes from and has no idea what it means, but I know and can provide the material for him.

[191] I point out to him that the hero motif appears throughout the dreams. He has a hero fantasy about himself which comes to the surface in the last dream. He is the hero as the great man with the long coat and with the great plan; he is the hero who dies on the field of honour at St. Jacob; he is going to show the world who he is; and he is quite obviously the hero who overcomes the monster. The hero motif is invariably accompanied by the dragon motif; the dragon and the hero who fights him are two figures of the same myth.

[192] The dragon appears in his dream as the crab-lizard. This statement does not, of course, explain what the dragon represents as an image of his psychological situation. So the next associations are directed round the monster. When it moves first to the left and then to the right the dreamer has the feeling that he is standing in an angle which could shut on him like open scissors. That would be fatal. He has read Freud, and accordingly he interprets the situation as an incest wish, the monster being the mother, the angle of the open scissors the legs of the mother, and he himself, standing in between, being just born or just going back into the mother.

[193] Strangely enough, in mythology, the dragon is the mother. You meet that motif all over the world, and the monster is called the mother dragon.7 The mother dragon eats the child again, she sucks him in after having given birth to him. The “terrible mother,” as she is also called, is waiting with wide-open mouth on the Western Seas, and when a man approaches that mouth it closes on him and he is finished. That monstrous figure is the mother sarcophaga, the flesh-eater; it is, in another form, Matuta, the mother of the dead. It is the goddess of death.

[194] But these parallels still do not explain why the dream chooses the particular image of the crab. I hold—and when I say I hold I have certain reasons for saying so—that representations of psychic facts in images like the snake or the lizard or the crab or the mastodon or analogous animals also represent organic facts. For instance, the serpent very often represents the cerebro-spinal system, especially the lower centres of the brain, and particularly the medulla oblongata and spinal cord. The crab, on the other hand, having a sympathetic system only, represents chiefly the sympathicus and para-sympathicus of the abdomen; it is an abdominal thing. So if you translate the text of the dream it would read: if you go on like this your cerebro-spinal system and your sympathetic system will come up against you and snap you up. That is in fact what is happening. The symptoms of his neurosis express the rebellion of the sympathetic functions and of the cerebro-spinal system against his conscious attitude.

[195] The crab-lizard brings up the archetypal idea of the hero and the dragon as deadly enemies. But in certain myths you find the interesting fact that the hero is not connected with the dragon only by his fight. There are, on the contrary, indications that the hero is himself the dragon. In Scandinavian mythology the hero is recognized by the fact that he has snake’s eyes. He has snake’s eyes because he is a snake. There are many other myths and legends which contain the same idea. Cecrops, the founder of Athens, was a man above and a serpent below. The souls of heroes often appear after death in the form of serpents.

[196] Now in our dream the monstrous crab-lizard moves first to the left, and I ask him about this left side. He says, “The crab apparently does not know the way. Left is the unfavourable side, left is sinister.” Sinister does indeed mean left and unfavourable. But the right side is also not good for the monster, because when it goes to the right it is touched by the wand and is killed. Now we come to his standing in between the angle of the monster’s movement, a situation which at first glance he interpreted as incest. He says, “As a matter of fact, I felt surrounded on either side like a hero who is going to fight a dragon.” So he himself realizes the hero motif.

[197] But unlike the mythical hero he does not fight the dragon with a weapon, but with a wand. He says, “From its effect on the monster it seems that it is a magical wand.” He certainly does dispose of the crab in a magical way. The wand is another mythological symbol. It often contains a sexual allusion, and sexual magic is a means of protection against danger. You may remember, too, how during the earthquake at Messina8 nature produced certain instinctive reactions against the overwhelming destruction.

[198] The wand is an instrument, and instruments in dreams mean what they actually are, the devices of man to concretize his will. For instance, a knife is my will to cut; when I use a spear I prolong my arm, with a rifle I can project my action and my influence to a great distance; with a telescope I do the same as regards my sight. An instrument is a mechanism which represents my will, my intelligence, my capability, and my cunning. Instruments in dreams symbolize an analogous psychological mechanism. Now this dreamer’s instrument is a magic wand. He uses a marvellous thing by which he can spirit away the monster, that is, his lower nervous system. He can dispose of such nonsense in no time, and with no effort at all.

[199] What does this actually mean? It means that he simply thinks that the danger does not exist. That is what is usually done. You simply think that a thing is not and then it is no more. That is how people behave who consist of the head only. They use their intellect in order to think things away; they reason them away. They say, “This is nonsense, therefore it cannot be and therefore it is not.” That is what he also does. He simply reasons the monster away. He says, “There is no such thing as a crab-lizard, there is no such thing as an opposing will; I get rid of it, I simply think it away. I think it is the mother with whom I want to commit incest, and that settles the whole thing, for I shall not do it.” I said, “You have killed the animal—what do you think is the reason why you contemplate the animal for such a long time?” He said, “Oh, well, yes, naturally it is marvellous how you can dispose of such a creature with such ease.” I said, “Yes, indeed it is very marvellous!”

[200] Then I told him what I thought of the situation. I said, “Look here, the best way to deal with a dream is to think of yourself as a sort of ignorant child or ignorant youth, and to come to a two-million-year-old man or to the old mother of days and ask, ‘Now, what do you think of me?’ She would say to you, ‘You have an ambitious plan, and that is foolish, because you run up against your own instincts. Your own restricted capabilities block the way. You want to abolish the obstacle by the magic of your thinking. You believe you can think it away by the artifices of your intellect, but it will be, believe me, matter for some afterthought.’ “And I also told him this: “Your dreams contain a warning. You behave exactly like the engine-driver or like the Swiss who were foolhardy enough to run up against the enemy without any support behind them, and if you behave in the same way you will meet with a catastrophe.”

[201] He was sure that such a point of view was much too serious. He was convinced that it is much more probable that dreams come from incompatible wishes and that he really had an unrealized incestuous wish which was at the bottom of this dream; that he was conscious now of this incestuous wish and had got rid of it and now could go to Leipzig. I said, “Well then, bon voyage.” He did not return, he went on with his plans, and it took him just about three months to lose his position and go to the dogs. That was the end of him. He ran up against the fatal danger of that crab-lizard and would not understand the warning. But I do not want to make you too pessimistic. Sometimes there are people who really understand their dreams and draw conclusions which lead to a more favourable solution of their problems.