— 8 —

THE DOPE ON DOPAMINE

I refer to my time as a purse junkie as a mistake, but I don’t regret it. What I learned completely changed my approach to money—and happiness.

I meticulously researched my first bag, spending hours on YouTube. When I made my purchase (a lime-green Penelope shopper), my heart was bursting with excitement. This was the first fancy thing I had ever owned, officially marking my entry into the middle class. I stayed up all night smelling the fabric and caressing the leather, whispering, “My precious” . . . You know what? When I write it out, it sounds nuts, so let’s move on.

That first purchase made me legitimately happy. But my second bag (a gold Ashley carryall) didn’t. I was so confused. I had spent just as much time researching it and spent just as much money, but it wasn’t the same. I didn’t get that same high. By the time I was on to bag five, it was such a nonevent I don’t even remember it. Soon, I got so bored of my purses I sold or gave away all but one.

I had inadvertently gotten on the Hedonic Treadmill.

When we buy something special or get a raise, we’re happy because we perceive a positive change in our life. Similarly, when something bad happens, like a blown tire or a health issue, that negative change bums us out. But over time, we get used to the new normal and return to our baseline level of happiness. Psychologists Philip Brickman, Dan Coates, and Ronnie Janoff-Bulman first noticed this phenomenon in a 1978 study in which they tracked the happiness levels of two groups: lottery winners and recently injured paraplegics. As expected, the lottery winners reported a much higher level of happiness than the control group, and the paraplegics a much lower level. But over time, both groups adapted to their circumstances, and after a year their self-reported happiness returned to the levels at which they were before their lives had changed.1

Happiness is relative. Understanding that not only explains the diminishing returns of luxury purse buying, it applies in all areas of your life. In the 1970s, Vicki Robin, author of the New York Times bestseller Your Money or Your Life, began running the finance seminars that made her a household name. She would ask the audience to write down how much they earned and how much they thought they needed to earn to be happy. On average, people thought they needed double what they earned. It didn’t matter if they made $30,000 or $100,000; the threshold was relative to their current salary.

So, are we simply incapable of being satisfied with our lot? On the surface, it seems so, but as I dug deeper, I realized that the Hedonic Treadmill—on which no matter how much we run, we always stay in place—is more than a psychological phenomenon. It’s biochemical.

BLAME YOUR BRAIN

Your brain is a complex machine and neuroscientists are only beginning to understand it. What neuroscientists do understand pretty well is the mesolimbic pathway, which is part of the reward system in the brain. It contains pathways that trigger feelings like cravings, hunger, desire, and pleasure. The mesolimbic pathway incentivizes us to seek food when we’re hungry and water when we’re thirsty. It’s also responsible for the positive reinforcement we feel when we get them.

Which brings us to dopamine. Dopamine, the “pleasure chemical,” is the main neurotransmitter coursing through the mesolimbic pathway. When something good happens, dopamine gets released and we feel pleasure. At least, that’s what we’ve been led to believe. In reality, it’s a bit more complicated. The mesolimbic pathway also contains a structure responsible for processing dopamine called the nucleus accumbens, which houses neural pathways sensitive to dopamine. These are the real gateways to pleasure and happiness. This distinction is why the narrative of “more dopamine = more happiness” isn’t actually true.

In 2006, neurologists in Germany conducted an experiment on the nucleus accumbens. What they found explained the Hedonic Treadmill. Subjects were asked to play a game of identifying simple objects like circles and triangles. If they won, they’d get one euro. If they lost, they got nothing. Before starting they were given a percentage likelihood of winning.

You would think that people would be pumped if they won money no matter what, right? Wrong. Turns out, if people were given a high chance (like 100 percent) of winning, when they did, an fMRI showed no additional activity in the nucleus accumbens’s dopaminergic receptors. Conversely, if they had a low chance of winning (like 25 percent) and they did, the fMRI showed a spike of activity in those same dopaminergic receptors. Conversely, if the person was given a high probability of winning (like 75 percent) and they didn’t, the fMRI showed a decrease in dopamine activity.

The nucleus accumbens reacts to both the presence of a positive stimulus and also the expectation of that stimulus. In other words, pleasure isn’t based on an absolute level of dopamine in the brain, but rather on the relative level versus the expected level of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens.

Relative, not absolute.

Yay for Cocaine!

The results were published in an academic paper titled “Prediction Error as a Linear Function of Reward Probability Is Coded in Human Nucleus Accumbens.”2 This title both amuses and nauseates me, as a former engineer and current writer, in its complete inaccessibility. Anyway, as boring as all the scientific terms are, this is one of the few attempts to study the brain’s reward system as it relates to finances.

In fact, we only know as much as we do about the human mesolimbic pathway because of research done in the context of addiction studies. Specifically, cocaine studies, funded by the DEA, CDC, and WHO, to understand and treat drug addicts.

So . . . yay for cocaine?

Cocaine, amphetamines, and other drugs operate by disrupting dopamine reuptake and reabsorption, causing the chemical to overwhelm the mesolimbic pathway and overstimulate its pleasure centers to the point of madness. But because the nucleus accumbens is involved, your brain resets to the new normal. That’s why the next time a cocaine user takes a hit, the high isn’t as strong. Their baseline has recalibrated; they need more cocaine to get the same high. Two things can happen next. Either the user gets bored by the decreasing effectiveness of the drugs and stops using—or they double down. Every addict knows that experience as “chasing their first high.”

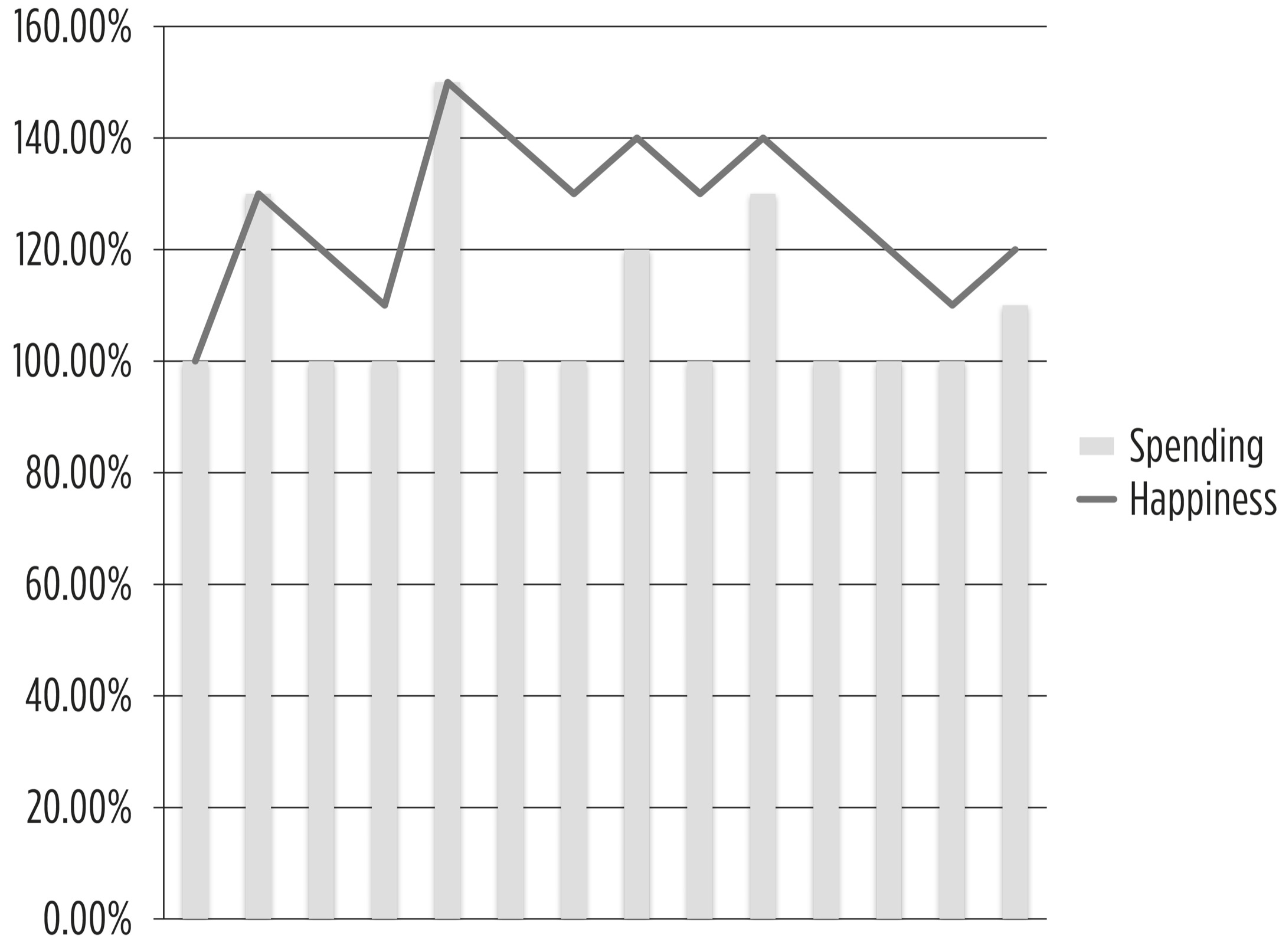

The Hedonic Treadmill works the same way. Each time you spend money on a big-ticket item, you get a little high, because your nucleus accumbens is detecting a change for the better. But after you buy that purse, or that TV, or that Xbox, it acclimatizes. Your level of pleasure steadily declines with each new purchase of a similar item; while the stimulus remains the same, your brain’s expectations have increased.

Not All Spending Is Created Equal

Here’s the part where I’m supposed to scold people who spend too much money. Sorry to disappoint. The lesson here isn’t exactly what you may think.

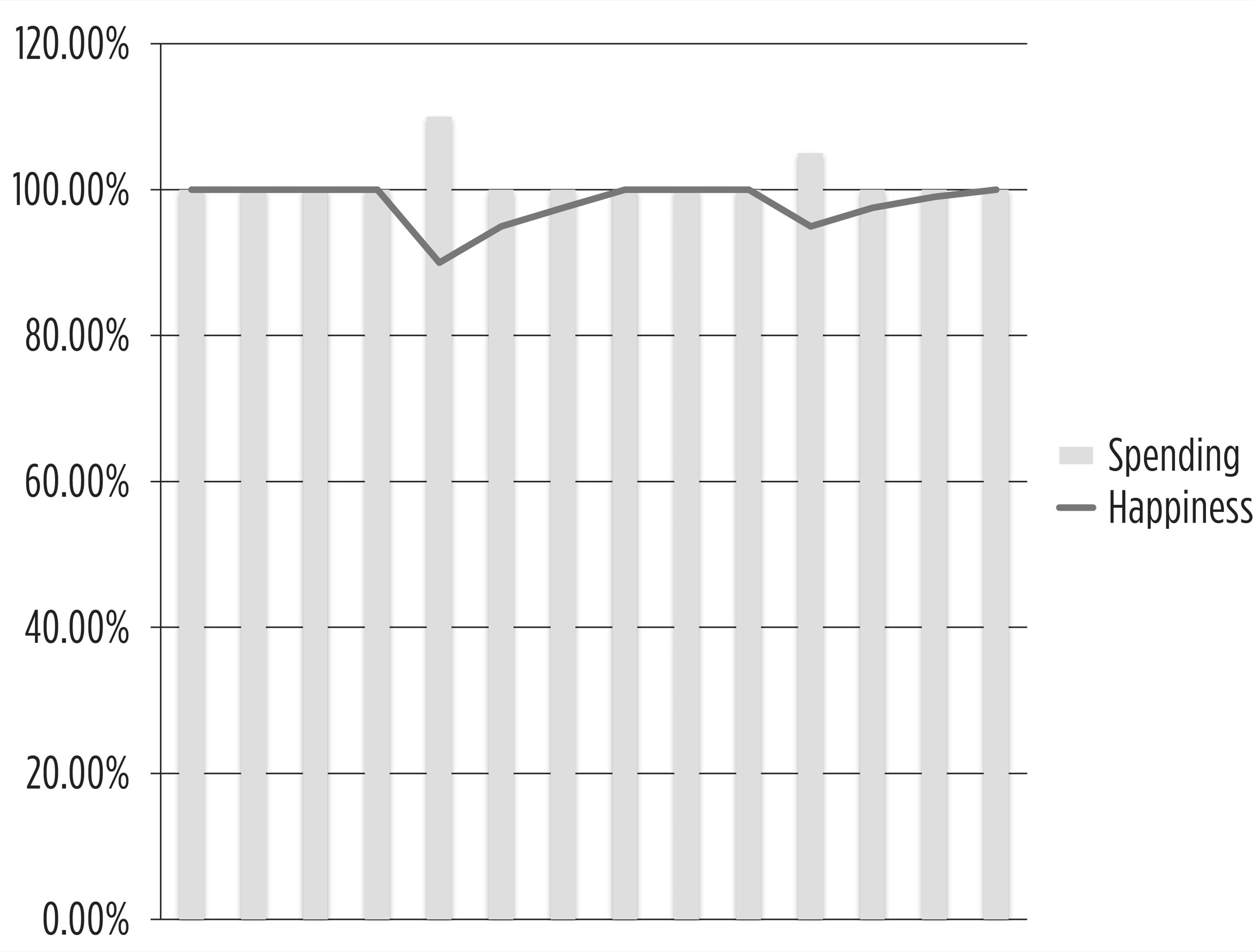

Once I figured out what was happening, I realized that this diminishing-happiness effect only applied to possessions—not to experiences. Maybe it’s because I spent most of my childhood stuck in small towns, but I’ve always loved to travel. When we were working, Bryce and I would plan two vacations a year to Europe or the Caribbean, with the bill for each averaging $2,500—not chump change, by any means. And I had a great time, every time. We looked forward to our next vacation, reading travel guides and watching No Reservations. And then the day would come and we’d be like, “Wow! We’re in Rome!” Afterward, we’d go through our photos over and over and compare notes of our warm, fuzzy memories. The point is, it always felt worth it. That spending didn’t have the same drop-off that spending on stuff did, so we kept doing it.

Around that time, I started to notice a strange pattern among my friends and family (which was later reinforced when I started my blog and readers emailed me their financial situation to analyze). The more stuff people owned, the unhappier and more stressed they tended to be. Conversely, the less stuff people owned and the more they spent on experiences like travel or learning new skills, the happier and more content they were. Possessions give you an initial burst of dopamine that fades as your nucleus accumbens acclimatizes, causing you to continuously chase that high. People who spend on experiences get way more bang for their buck.

Stuff tends to snowball, too. I have a friend who collects art, but it’s never just about the piece; he also has to pay for it to be framed, reinforce a wall in his condo so it’s strong enough to support it, buy special lights to display it the way the artist intended, insure it . . . The list goes on and on. And every time he finds out about a new expense, he flies into a rage about the scuzzy vendors “taking advantage” of him!

Not all spending is created equal. Unless you are in true dire straits, day-to-day expenses like rent, groceries, heating, electricity, etc. don’t tend to bring you great happiness or unhappiness. At a certain point, they blend into the background. These are baseline costs.

Spending increases your happiness when it brings something new to your life, whether that’s a possession or an experience. These are splurges. However, that happiness is temporary for possessions but not for experiences.

Some spending decreases your happiness. These expenses—like insurance and maintenance—are necessary when you own things. Nobody enjoys spending money on a flooded basement or a flat tire. They are unexpected costs.

When I was growing up, I thought the key to happiness was more stuff. If one Coke could make me so happy, then thirty Cokes should make me thirty times as happy! But the truth is, if someone had given me thirty Cokes, I would have panicked and started digging a hole under our chicken coop to hide my fortune from my neighbors. Then I would have sat on my porch, forever on guard for anyone who looked suspicious to keep them from murdering me and my family to steal my reserves.

That’s the problem with possessions. You get the initial bump, but then it fades, and if that possession is expensive, you worry about it. If it breaks, you have to spend money to fix it. If, for example, one of the chickens pecked open one of the Coke cans, I would have had to kill that chicken. Then I’d have been down one can of Coke and one chicken, which we would have had to pay money to replace. Possessions convert splurges into unexpected costs.

Think of my friend the art collector. His initial purchase gave him a burst of happiness. But over time, that happiness faded because his nucleus accumbens acclimatized.

When the expensive purchase caused him to spend money to insure and maintain it, the spending didn’t make him happy. It had the exact opposite effect.

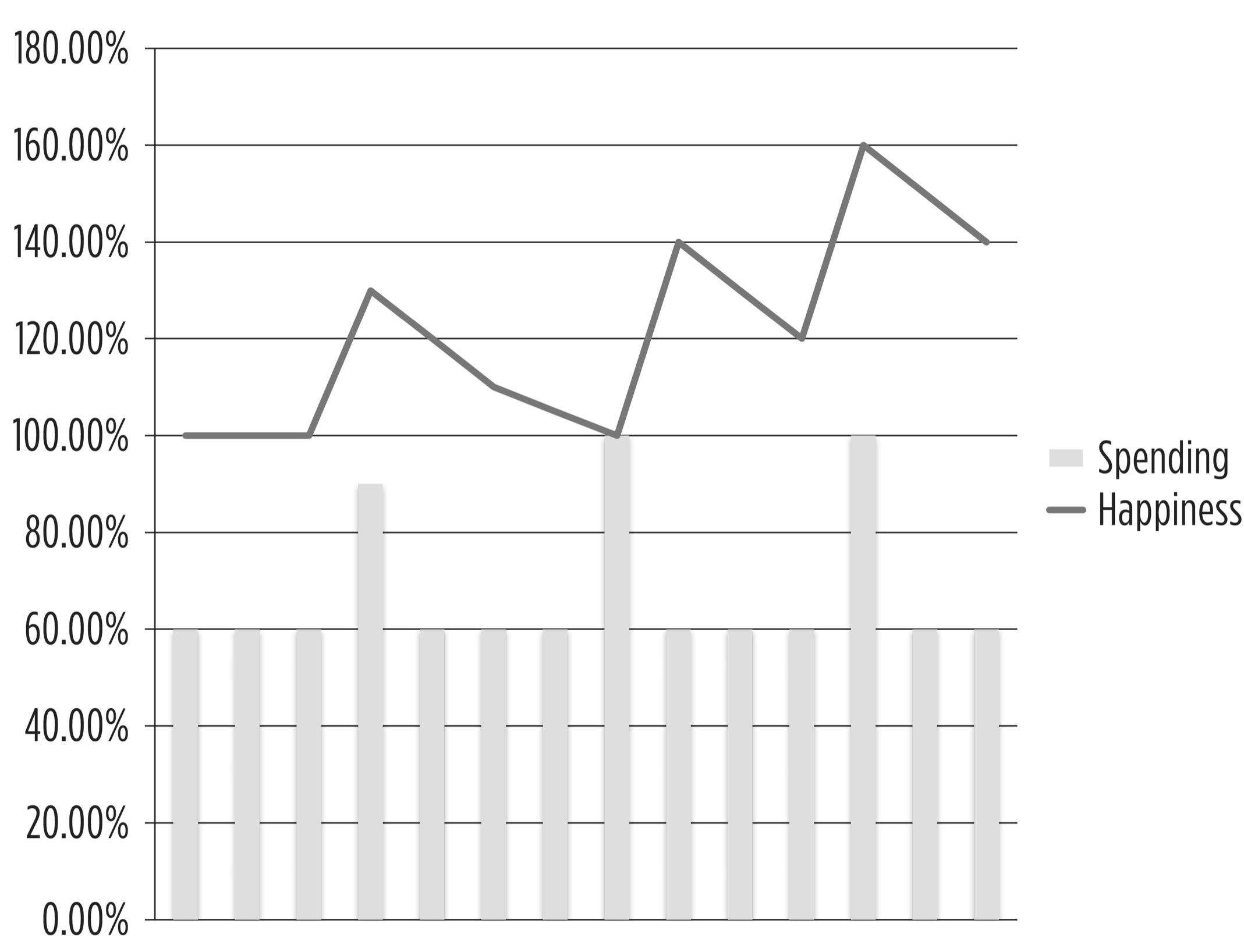

But now let’s look at someone who spends money on experiences. Since every experience is different, your happiness spikes each time. Not only that, once the experience is over, you don’t own anything, and as a result you don’t need to protect it. So, you don’t get that conversion of splurge–to–unexpected cost spending. Instead, your spending and happiness look like this:

Not All Cuts Hurt

This realization lit up my brain with possibilities. If all spending isn’t created equal, does that mean not all cuts in spending will hurt? If certain expenditures don’t increase your happiness, doesn’t that mean eliminating them won’t affect it one way or the other? If certain expenditures decrease your happiness, wouldn’t eliminating them make you happier?

Everyone thinks budgeting is like being on a diet. If you spend less, you’re less happy. But in actuality, certain spending doesn’t decrease your happiness. In other words, not all cuts hurt.

One summer in Toronto, the Transit Commission, which runs the subways, decided to go on strike. For weeks, the city’s subway system ground to a halt and TV stations filled with angry Canadians (it doesn’t happen often, but when it does, watch out!). Rather than pay for taxis daily, I decided to jog to work. To my surprise, it didn’t take as long, nor was it as difficult, as I’d imagined. I even lost weight and was able to cancel my gym membership. So, when the TTC got back online, I continued jogging to work, saving almost $200 every month that summer. I felt physically amazing and loved seeing those extra dollars in my bank account.

Remember the closet exercise from chapter 2? I asked you to track your clothing usage for a month to sort out what you’re actually wearing regularly. Now pretend that a fire started in your closet and destroyed your clothes. If you lost the stuff on the left, well, you barely wore them anyway. You might be bummed, but it wouldn’t really affect your day-to-day life. Conversely, if you lost all the clothes to the right, you would feel it. They were the pieces you wore every day. Whenever you picked an outfit, you’d miss the ones that got burned up.

Not all spending is created equal. And as a result, not all cuts are created equal. Some cuts hurt deeply. Others don’t hurt at all.

This Time It’s Personal

I have a confession to make. I find personal finance books annoying. They tend to make you feel bad about spending money, berating you for buying a cup of coffee every morning. If only you’d invest it, that $3.50 would be worth a hundred thousand in thirty years!

Bull. Shit. While I don’t doubt the math, universal advice like that is idiotic. Some people don’t care about coffee (like me). But other people love it—it truly makes their day better. I’m from Sichuan Province, where all our food is covered in chili oil. If someone told me that not eating spicy foods would extend my life expectancy, I’d respond, “Why would I want to live a longer life without my favorite food?”

The secret to budgeting is not to imitate some template but to find the budget that works for you.

Step 1: Eliminate Baseline Costs That Don’t Make You Happy

First, find the easy stuff. Pore over your monthly expenses and look for spending that can be easily eliminated without any real hit to your quality of life. Bank fees are a good example. By opening accounts at zero-fee online banks or credit unions, you can eliminate bank fees (which will make you feel awesome):

Give it a shot. Sometimes you’ll find spending you weren’t even aware of. I once had a friend discover she was still paying for hosting for a website she no longer owned!

Here are a few suggestions to get you started.

-

Bank fees

-

Subscriptions to things you no longer use

-

Cable packages for channels you don’t watch

-

Landline (who uses landlines anymore?)

Step 2: Eliminate Baseline Costs That Hurt but You’ll Get Used To

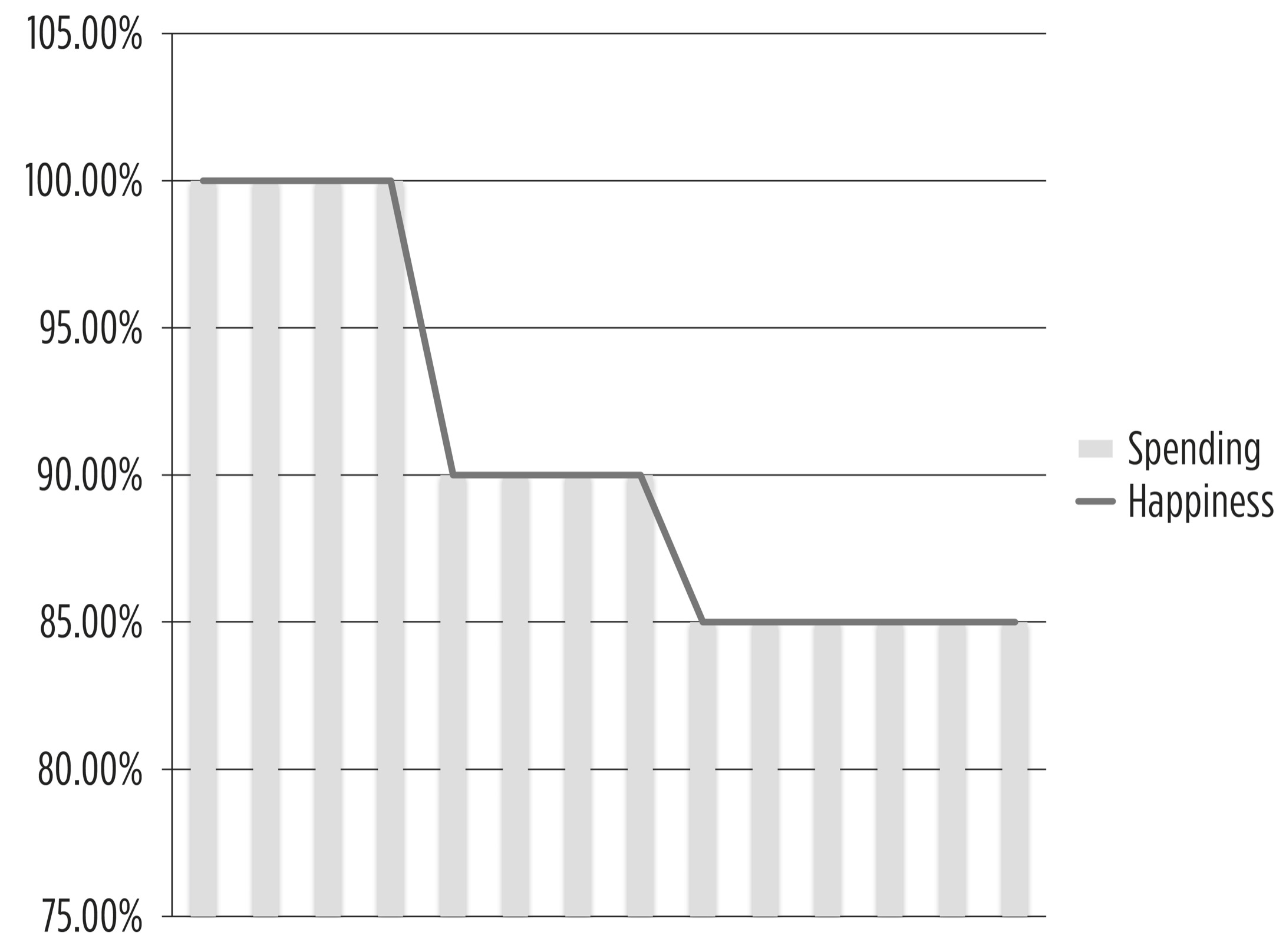

Next find ways to make expense cuts that may cause you some amount of discomfort but you’ll get used to. For me, it was jogging to work. For you, it may be cooking at home, biking to work, or buying used things instead of new. There will be an adjustment period, but once your nucleus accumbens kicks in, your happiness level will return to baseline.

There are some expenses that you’ll find simply can’t be cut without permanently affecting your general well-being. If for whatever reason I lost access to spicy Sichuan food, my happiness level would look like this:

Finding the appropriate expenses to cut for your personal situation is the key to successful budgeting. None of this “just quit buying coffee” crap. Your spending is personal and specific to you, and no book can tell you exactly what to do, no matter how hard they try to convince you. The only way to find out is to try it and give it some time. If you find yourself missing that thing too much, undo it!

Here are a few items that may fall under this category.

-

Buying lunch at work

-

Eating out

-

Going out with friends

-

Gym membership

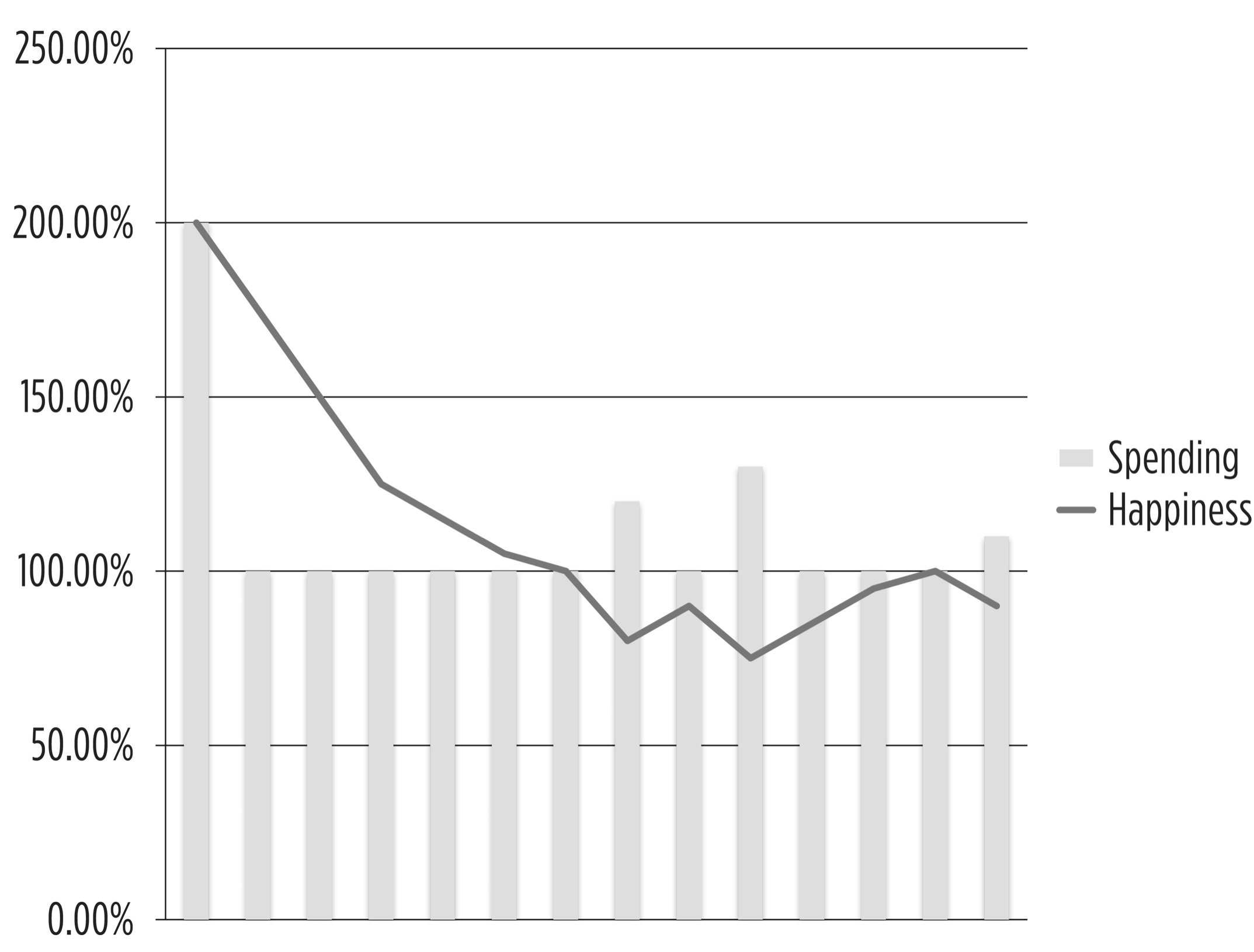

Step 3: Reduce the Expensive Things You Own That Cost You Money

In this step, we take a hard look at the expensive items you own. Specifically, things that cost you money to maintain, insure, repeatedly fill up with premium gas, etc. The goal is to reduce or eliminate unexpected costs as much as possible.

The two most common items people own that contribute to their unexpected costs are their car and their home.

Let’s talk about cars for a minute. Readers often write in to say how they try to save and be responsible, but bad things continue happening to keep them from getting ahead. Digging deeper, often it turns out that their overreliance on their cars is the cause of their bad luck. Not only do cars decrease in value the second you drive them off the lot, they are money sinks. One blown radiator can destroy months of diligent saving.

Sometimes, people misinterpret my advice as meaning they have to get rid of their cars. Not so. Remember, most of a car’s unexpected costs are dependent on miles driven rather than ownership of the car itself. Gas and maintenance costs go down the less you drive, and you can reduce your insurance premiums if you don’t drive every day. If you can find a way to use your car less by, say, biking to work or taking public transportation, you can keep your car while reducing most of its unexpected costs. Plus, it’s good for the environment and your waistline. The goal is to turn this . . .

. . . into this:

A house is the second major item in this category, but housing is such a big topic that we devoted an entire chapter to it (chapter 9). In short, people justify the unexpected costs of owning a house by pointing out that houses tend to appreciate in value, so the costs are always offset by this investment, while renting is throwing money away. We’ll debunk this myth in the next chapter.

Step 4: Add Splurges

By the time you’ve reached this step, you’ve gone through your spending and found what you can cut painlessly. You’ve also realized what you can’t live without and added it back. Finally, you’ve looked at your most expensive items (cars, mainly) and either reduced your reliance on them or eliminated them completely.

Now let’s have some fun! Add up all the spending you’ve cut. Then take a part of that and allocate it toward splurges. You don’t have to decide what you’re going to spend it on (in fact, it’s better if you don’t so you can make it spontaneous), but this is “fun money” you can do whatever you want with. For me, this usually means traveling, but it could be anything. Want to go to a concert? Go for it! Go scuba diving? Sure! Go to Vegas for a wild weekend? Well, clear it with your significant other first, but why the hell not? I would encourage you to splurge on experiences over possessions to get lasting happiness, but it’s up to you. As long as the amount allocated is less than the amount you saved by cutting, then you have successfully saved money while increasing happiness!

UNDERSTAND YOUR BRAIN, UNDERSTAND YOUR BUDGET

Budgeting does not have to be the soul-sucking chore that everyone thinks it is, because budgeting isn’t simply about cutting. You just need to understand two truths about the human brain, namely:

-

How you derive satisfaction from your spending is determined by your brain.

-

Everyone’s brain is different.

The process of finding your optimal budget is different for everyone. My budget will not work for you and vice versa. But by understanding the link between dopamine, happiness, and spending, and by following the steps outlined in this chapter, you will hopefully take a budget that looks like this, the budget of a typical consumer who owns too much and is perpetually unhappy because of high baseline costs and unexpected costs . . .

. . . and turn it into this, one with low baseline costs, no unexpected costs, and lots of happiness-producing splurges:

In the process, you will discover the most efficient way of turning dollars into dopamine that works for you and you alone. If you’re anything like me, you will find it incredibly liberating, and you’ll be happier and healthier, with more money than you ever thought possible.

Now on to something a bit controversial. It’s time to talk about why owning a home sucks.

CHAPTER 8 SUMMARY

-

Spending money is addictive because our brains reset our expectations and we no longer get the same amount of dopamine with repeated spending.

-

There are three different types of spending:

-

Baseline Costs: Day-to-day costs that you get used to, like rent or utilities. These don’t increase or decrease your happiness.

-

Splurges: An occasional purchase that makes you happier.

-

Unexpected Costs: Unexpected costs to fix something that’s gone wrong. These decrease your happiness.

-

-

How people budget varies per individual. You have to experiment and see for yourself which cuts hurt and which don’t.

-

To find a budget that works for you:

-

Step 1: Eliminate baseline costs that don’t make you happy.

-

Step 2: Eliminate baseline costs that may hurt to get rid of but that you’ll get used to living without.

-

Step 3: Eliminate as many unexpected costs as you can by reducing high-maintenance things you own.

-

Step 4: Add splurges back into your life.

-