Greenscapes & Gardens

Typically, yard renovation begins with taking a hard look at what you have in your yard and then clearing away the old to make way for the new. To that end, we walk you through clearing land, including the basics on how to remove the nuisance trees, invasive plants, and thorny brush that stand in the way.

Sometimes, clearing amounts to one tall task: taking down a tree. Perhaps removing the tree will open up a sightline and allow sunlight to brighten a gloomy corner of your yard. If the job qualifies as DIY, we show you how to fell a tree correctly. If your trees and shrubs just need judicious pruning to restore their ornamental shape, we’ll show you how to do that too.

Once the subtraction is complete in your yard, it’s time for addition. Planting trees is rewarding and benefits your property by providing shade, increasing property value and curb appeal, and blocking wind. You’ll learn how to plant a balled-and-burlapped tree and how to create a windbreak.

Finally, we explain how to plant and care for annuals and perennials. You’ll find out how to create landscaping and garden beds, how to use edging, and more. And to help you conserve water, we show you how to practice waterwise gardening.

In this chapter:

Clearing Brush

Nuisance trees, invasive plants, and thorny groundcovers latch on to your land and form a vegetative barrier, greatly limiting the usefulness of a space. Before you can even think of the patio plan or garden plot you wish to place in that space, you’ll need to clear the way. If the area is a sea of thorny brush or entirely wooded, you’ll probably want to hire an excavator, logger, or someone with heavy-duty bulldozing equipment to manage the job. But on suburban plots, brush can usually be cleared without the need for major machinery.

Dress for protection when taking on a brush-clearing job. You never know what mysteries and challenges reside on your property behind the masses of branches and bramble. Wear boots, long pants, gloves, long sleeves, and eye protection. Follow a logical workflow when clearing brush—generally, clean out the tripping hazards first so you can access the bigger targets more safely.

Cutting and removal tools used for brush clearing should be scaled for the job you’re asking them to do. Simple hand tools can handle much of the work, but for bigger jobs having the right power tools is a tremendous worksaver. Tools shown here include: electric lopper (cordless) (A); loppers (B); bow saw (C); garden (bow) rake (D); chainsaw (cordless) (E).

How to Clear Brush

How to Clear Brush

Begin by using a tree pruner to cut woody brush that has a diameter of less than 1 1/2". Cut the brush and/or small trees as close to the ground as possible, dragging brush out of the way and into a pile as you clear.

Next, clear out larger plants—brush and trees with a diameter of about 1 1/2" to 3 1/2". Use a bow saw or chain saw to cut through the growth, and place the debris in a pile. Trees larger than 4" diameter should be left to grow or removed under the supervision of a professional.

Use a heavy-duty string trimmer or a swing-blade style weed cutter to cut tangled shoots, weeds, and remaining underbrush from the area.

Clear the cut debris and dispose of it immediately. Curbside pickup of yardwaste usually requires that sticks or branches be tied up into bundles no more than 3 ft. long. If you plan to install a hardscape surface, make sure the brush does not grow back by using a nonselective herbicide to kill off remaining shoots or laying landscape fabric.

Tree Removal

Removing trees is often a necessary part of shaping a landscape. Diseased or dead trees need to be removed before they become a nuisance and to maintain the appearance of your landscape. Or, you may simply need to clear the area for any of a variety of reasons, including making a construction site, allowing sunshine to a planting bed, or opening up a sightline.

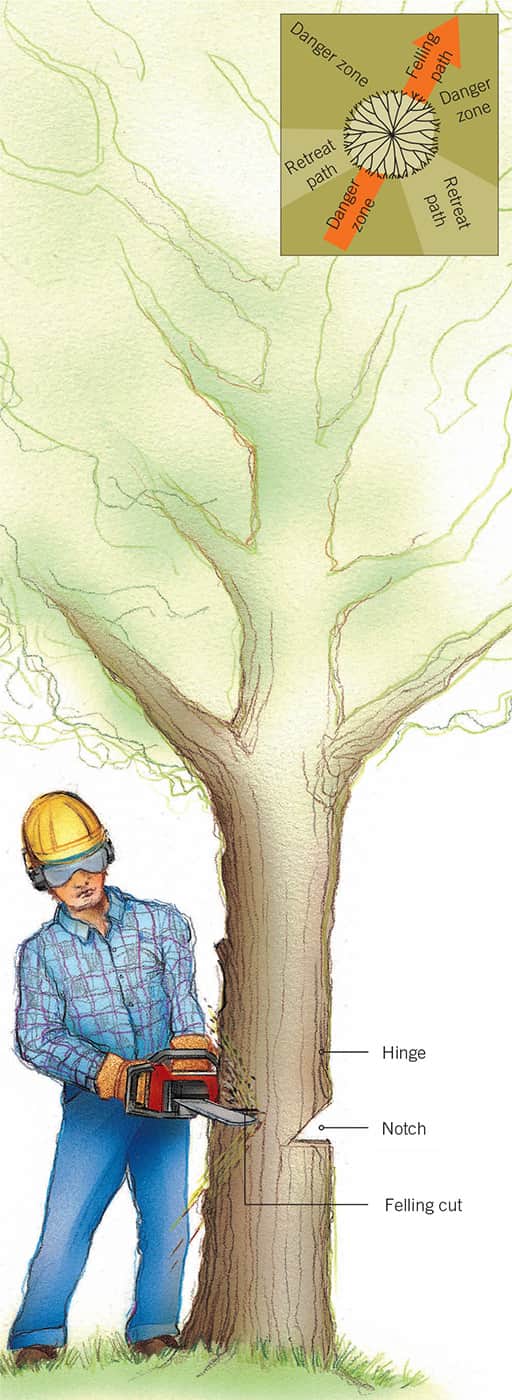

If you need to remove a mature tree from your yard, the best option is to have a licensed tree contractor cut it down and remove the debris. If you are ambitious and careful, small trees with a trunk diameter of less than 6 inches can present an opportunity for DIY treecutting. The first step in removing a tree is determining where you want it to fall. This area is called the felling path; you’ll also need to plan for two retreat paths. Retreat paths allow you to avoid a tree falling in the wrong direction. To guide the tree along a felling path, a series of cuts are made in the trunk. The first cut, called a notch, is made by removing a triangle-shaped section on the side of the tree facing the felling path. A felling cut is then made on the opposite side, forming a wide hinge that guides the fall of the tree.

Always follow manufacturer’s safety precautions when operating a chainsaw. The following sequence outlines the steps professionals use to fell a tree and cut it into sections. Always wear protective clothing, including gloves, hardhat, safety glasses, and hearing protection when felling or trimming trees. And make certain no children or pets are in the area.

How to Fell a Tree

How to Fell a Tree

Remove limbs below head level. Start at the bottom of the branch, making a shallow up-cut. Then cut down from the top until the branch falls.

NOTE: Hire a tree service to cut down and remove trees with a trunk diameter of more than 6".

Use a chain saw to make a notch cut one-third of the way through the tree, approximately at waist level. Do not cut to the center of the trunk. Make a straight felling cut about 2" above the base of the notch cut, on the opposite side of the trunk. Leave a 3"-thick “hinge” at the center.

Drive a wedge into the felling cut. Push the tree toward the felling path to start its fall, and move into a retreat path to avoid possible injury.

Standing on the opposite side of the trunk from the branch, remove each branch by cutting from the top of the saw, until the branch separates from the tree. Adopt a balanced stance, grasp the handles firmly with both hands, and be cautious with the saw.

To cut the trunk into sections, cut down two-thirds of the way and roll the trunk over. Finish the cut from the top, cutting down until the section breaks away.

Pruning Trees

Pruning trees and shrubs can inspire new growth and prolong the life of the plant. It may surprise you that the entire plant benefits when you remove select portions. Regular pruning also discourages disease and improves the plant’s overall appearance.

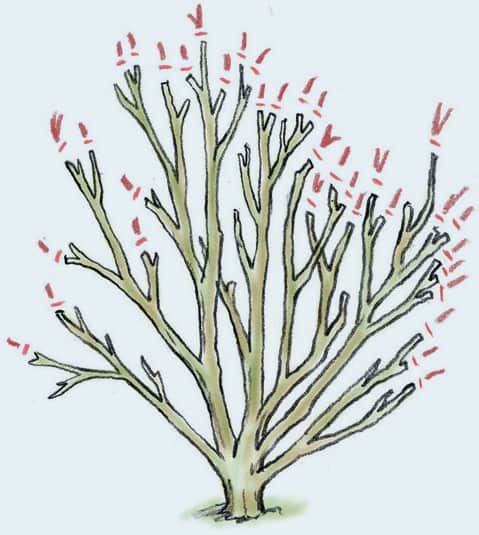

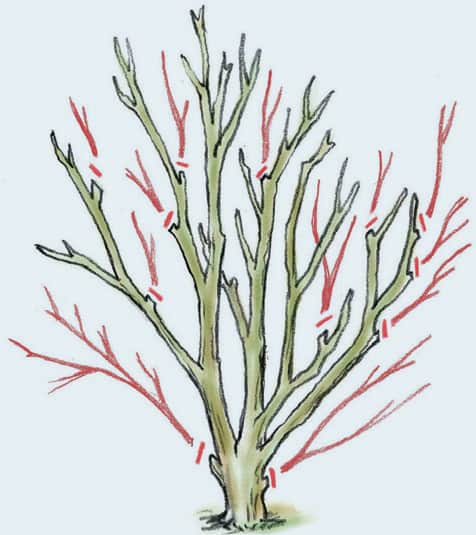

Timing and technique when pruning will, quite literally, mold the future of the shrub or tree. The trick to properly pruning trees and shrubs is to remember that less is more. Instances that warrant pruning include: pinching off the ends of plants (to maintain a bushy look); restoring an ornamental’s shape with clean-up cuts; and removing rubbing tree branches, where abrasion is an open wound for disease to enter.

Light, corrective pruning means removing less than 10 percent of the tree or shrub canopy. This can be performed at any time during the year. However, when making more severe cuts, such as heading back, thinning, or rejuvenating, prune when plants are under the least amount of stress. That way, trees and shrubs will have time to heal successfully before the flowering and growing season. The best time to perform heavy pruning/trimming on most woody plants, flower trees, and shrubs is during late winter and early spring.

Regular pruning of trees and shrubs not only keeps the plants looking neat and tidy, it makes them healthier.

How to Prune a Tree

How to Prune a Tree

Start by undercutting from beneath the limb with your bow saw or chain saw.

Finish the cut from above. This keeps the bark from tearing when the limb breaks loose.

Trim the stub from the limb so it’s flush with the branch collar.

Planting Trees

Trees and shrubs are structural elements that provide many benefits to any property. Aside from adding structural interest to a landscape, they work hard to provide shade, block wind, and form walls and ceilings of outdoor living areas. Whether your landscape is a blank canvas or you plan to add trees and shrubs to enhance what’s already there, you’ll want to take great care when selecting what type of tree you plant, and how you plant it.

A substantially sized tree might be your greatest investment in plant stock, which is more reason to be sure you give that tree a healthy start by planting it correctly. Timing and transportation are the first issues you’ll consider. The best time to plant is in spring or fall, when the soil is usually at maximum moistness and the temperature is moderate enough to allow roots to establish. When you choose a tree or shrub, protect the branches, foliage, and roots from wind and sun damage during transport. When loading and unloading, lift by the container or rootball, not the trunk. You may decide to pay a nursery to deliver specimens if they are too large for you to manage, or if you are concerned about damaging them en route to your property.

Trees and shrubs are packaged three different ways for sale: with a bare root, container-grown, and balled-and-burlapped. Bare root specimens (left) are the most wallet-friendly, but you must plant them during the dormant season, before growing begins. Container-grown plants (center) are smaller and take years to achieve maturity, but you can plant them any time—preferably during spring or fall. Balled-and-burlapped specimens (right) are mature and immediately fill out a landscape. They are also the most expensive.

How to Plant a Balled-and-Burlapped Tree

How to Plant a Balled-and-Burlapped Tree

Use a garden hose to mark the outline for a hole that is at least two or three times the diameter of the rootball. If you are planting trees with shallow, spreading roots (such as most evergreens) rather than a deep taproot, make the hole wider. Dig no deeper than the height of the rootball.

Amend some of the removed soil with hydrated peat moss and return the mixture to build up the sides of the hole, creating a medium that is easy for surface roots to establish in. If necessary (meaning, you dug too deep) add and compact soil at the bottom of the hole so the top of the rootball will be slightly above grade when placed.

Place the tree in the hole so the top of rootball is slightly above grade and the branches are oriented in a pleasing manner. Cut back the twine and burlap from around the trunk and let it fall back into the hole. Burlap may be left in the hole—it will degrade quickly. Non-degradable rootball wrappings should be removed.

Backfill amended soil around the rootball until the soil mixture crowns the hole slightly. Compress the soil lightly with your hands. Create a shallow well around the edge of the fresh soil to help prevent water from running off. Water deeply initially and continue watering very frequently for several weeks. Staking the tree is wise, but make sure the stake is not damaging the roots.

Planting Windbreaks

Wind saps heat from homes, forces snow into burdensome drifts, and can damage more tender plants in a landscape. To protect your outdoor living space, build an aesthetically pleasing wall—a “green” wall of tress and shrubs—that will cut the wind and keep those energy bills down. Windbreaks are commonly used in rural areas where sweeping acres of land are a runway for wind gusts. But even those on small, suburban lots will benefit from strategically placing plants to block the wind.

Essentially, windbreaks are plantings or screens that slow, direct, and block wind from protected areas. Natural windbreaks are comprised of shrubs, conifers, and deciduous trees. The keys to a successful windbreak are: height, width, density, and orientation. Height and width come with age. Density depends on the number of rows, type of foliage, and gaps. Ideally, a windbreak should be 60 to 80 percent dense. (No windbreak is 100 percent dense.) Orientation involves placing rows of plants at right angles to the wind. A rule of thumb is to plant a windbreak that is ten times longer than its greatest height. And keep in mind that wind changes direction, so you may need a multiple-leg windbreak.

A stand of fast-growing trees, like these aspens, will create an effective windbreak for your property just a few years after saplings are planted.

How to Plant a Windbreak

How to Plant a Windbreak

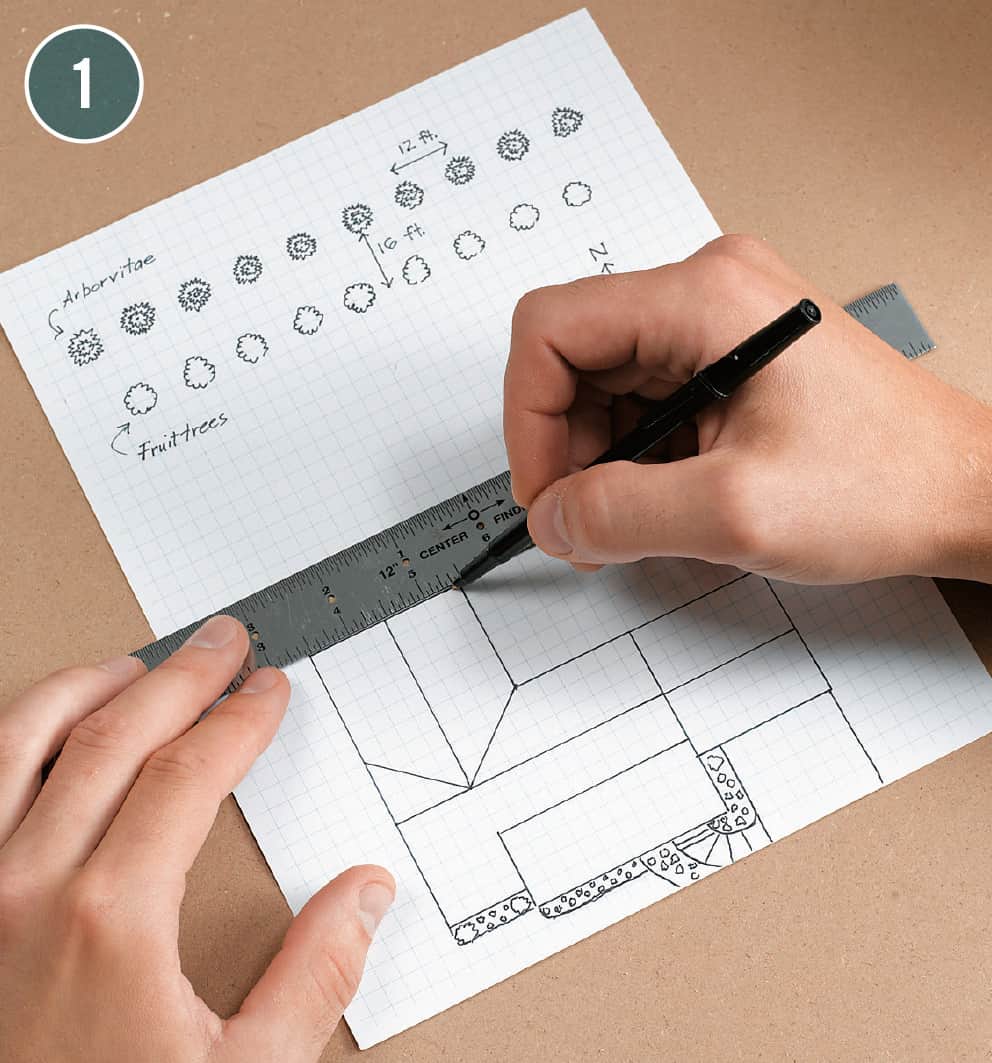

Before you pick up a shovel, draw a plan of your windbreak, taking into consideration the direction of the wind and location of nearby structures. Windbreaks can be straight lines of trees or curved formations. They may be several rows thick, or just a single row. If you only have room for one row, choose lush evergreens for the best density. Make a plan.

Once you decide on the best alignment of trees and shrubs, stake out reference lines for the rows. For a three-row windbreak, the inside row should be at least 75 ft. from buildings or structures, with the outside row 100 to 150 ft. away. Within this 25 to 75 ft. area, plant rows 16 to 20 ft. apart for shrubs and conifers and no closer than 14 ft. for deciduous trees. Within rows, space trees so their foliage can mature and eventually improve the density.

Dig holes for tree rootballs to the recommended depth (see page 37). Your plan should arrange short trees or shrubs upwind and taller trees downwind. If your windbreak borders your home, choose attractive plants for the inside row and buffer them with evergreens or dense shrubs in the second row. If you only have room for two rows of plants, be sure to stagger the specimens so there are no gaps.

Plant the trees in the formation created in your plan. Follow the tree and shrub planting techniques on page 37. Here, a row of dwarf fruit trees is being planted in front of a row of denser, taller evergreens (Techny Arborvitae).

Planting Annuals

An annual is any plant that completes its life cycle in one growing season. The term “annual” is usually used to refer to long-blooming flowering plants, many of which hail from tropical areas. These flowers have the ability to bring instant gratification anywhere they are placed—from your doorstep to the mailbox at the end of the driveway. They are often used as exclamation points in a landscape.

Annuals come in almost any color imaginable, and most of their impact comes from their showy flowers. But this group of plants also offers a wide range of leaf colors, growth habits, and textures. You can use them in mixed plantings for a bouquet effect or in mass groupings where you want a large area of a single color. They make great container plants and are good anywhere you want an instant show. You will often see annuals named as part of a “series.” Annuals that are part of a series all have similar growth characteristics but tend to have different flower colors.

Like vegetables, annuals can be classified as cool-season or warm-season plants based on their tolerance of cool air and soil temperatures. Cool-season annuals, which include pansies, snapdragons, and calendulas, do better in mild temperatures and can quickly deteriorate in hot weather. Warm-season annuals such as marigolds, zinnias, and impatiens grow and flower best in warm weather and do not tolerate any frost.

Planting a full bed of colorful annuals takes a bit of effort every spring, but the blossoms will delight you for most of the growing season. Interspersing the annual flowers with shrubs or even perennials gives a nice contrast and sense of composition.

Growing Annuals

Most annuals prefer well-drained soil that is rich in organic matter. Add a 2- to 4-inch layer of compost and mix it into the top 8- to 12-inches of soil the first year, adding a 1- to 2-inch layer of compost before planting in subsequent years. You can cover the bed with organic mulch, such as shredded bark, pine straw, or cocoa bean hulls, to reduce moisture evaporation and suppress weed growth. Just make sure the mulch doesn’t overwhelm the small plants and adds to their beauty rather than detracting from it.

Some larger-seeded annuals are easy to start from direct seeding. These include cosmos, marigold, morning glory, nasturtium, sunflower, and zinnia. Smaller-seeded annuals such as petunia, impatiens, and lobelia are more difficult to sow and require longer growing times before they flower. They need to be started indoors or purchased as plants in spring in order to get flowers by midsummer.

Most warm-season annuals should be seeded indoors 6 to 8 weeks before the last spring frost, but some require 10 to 12 weeks or more. Tender annuals should not be planted outdoors until all danger of spring frost has passed. Even if they are not injured by low temperatures, they will not grow well until the soil warms. Cool-season annuals will tolerate lower temperatures, but even they don’t like a hard frost. They can usually be planted outdoors about a week or two before the last expected spring frost date.

Plants started inside or purchased from a garden center need to be hardened off before planting them outdoors. Move the plants outside to a sheltered spot for a few hours, taking them back inside at night. Increase the outside time a little each day. After about a week, the plants should be tough enough to plant outdoors.

Tips for Planting Annuals

To remove annual seedlings, gently pop the young plants from their cell-packs by squeezing the bottoms and pushing up. Do not grab plants by their tender stems or leaves.

Plants growing in peat pots can be planted pot and all, but remove the upper edges of peat pots so that the pot will not act as a wick, pulling water away from the roots.

When planting annuals, plant at the same depth they were growing in the containers. If your growing medium is properly prepared, it will be loose enough that you can easily dig shallow planting holes with your fingers. For gallon pots, use a trowel, spade, or cultivator.

Pinch off any flowers or buds so the plant can focus its energy on getting its roots established rather than flowering, then water well.

Care of Annuals

Weeding. Weeding is probably the biggest maintenance chore with annuals; these plants do not compete well with weeds. Keep garden beds weed free by pulling regularly or covering the soil with organic mulch. Remember to keep the mulch away from the plants’ stems.

Watering. Most annuals need at least 1 to 1 1/2 inches of water per week from rain or irrigation. More may be needed during very hot weather and as the plants get larger. Water thoroughly and deeply to promote strong root growth. Allow the soil surface to dry before watering again. Soaker hoses and drip irrigation that apply water directly to the soil are best. Overhead irrigation destroys delicate blooms and can contribute to many fungi and molds. Watering is best when completed in the morning hours, so foliage has a chance to dry before cooler evening temperatures set in.

Feeding. Annuals put a lot of energy into blooming and require regular applications of nutrients. An easy way to provide annuals with the nutrients they need is to use a slow-release, or time-released, fertilizer at planting time. One application will slowly release nutrients with every watering. Although these fertilizers cost more than other types, they are usually worth the investment to save yourself from having to apply biweekly liquid fertilizer applications. The newer annuals require high soil fertility to do their best. Apply a slow-release fertilizer at planting time, mixing it in with the soil, and plan to follow up with biweekly applications of a water-soluble fertilizer.

Grooming. Because they are only around for a few months, most annuals don’t require a lot of grooming. Some of the taller types may need staking or support systems of some type. Staking is best done at planting time to avoid damaging roots. Some annuals benefit from pinching to promote bushiness. This list includes petunias and chrysanthemums. In general, pinching any plant that has become too leggy or too tall will make it bushier and more compact. One grooming task almost all annuals will benefit from is deadheading.

Planting Perennials

A plant that is perennial will survive more than one year, and technically can include trees, shrubs, grasses, bulbs, and even some vegetables. In gardening, the term “perennial” is usually used to describe herbaceous flowering plants that are grown specifically for their ornamental beauty. Typical perennials include daylilies, hostas, delphiniums, and yarrow.

Unlike annuals, perennials do not bloom throughout the growing season. Their bloom period can range anywhere from a week to a month or more. Many people shy away from perennials because of their higher initial cost. The extensive choices can also be overwhelming. But the fact that perennials live on from year to year provides several advantages. You will save the labor, time, and expense involved in replanting every year. Your garden will have continuity and a framework to work within. But the most appealing thing about using perennials is the astonishing array of colors, shapes, sizes, and textures available.

The tops of herbaceous perennials often die in the fall, but the roots survive the winter and send up new growth during the spring. Some herbaceous perennials grow a rosette of foliage (small leaves that grow along the base of the plant, similar to what biennials grow) after the stems die off.

For home landscaping, the term perennial is typically used to mean flowering plants that return anew every growing season after dying back at the end of the previous growing period.

Perennials can be divided into evergreen and deciduous. Perennials that keep their foliage all year-round are evergreen perennials. Deciduous perennials lose their foliage during the fall or winter and produce new top growth in spring.

Perennials are a very diverse and versatile group of plants. There are perennials that will thrive in every soil type, from full sun to full shade. This sunny border includes daylilies, chrysanthemums, and coneflowers.

Creating a Perennial Border

As versatile as perennials are, the spot where they really shine is in a perennial border. A perennial border is a wonderful way to bring beauty to your landscape and enjoy these fascinating plants throughout the year. The goal with a perennial border is to create a garden with interest from early spring through fall, and even into the winter. A border is usually more interesting if it contains a wide variety of heights, colors, and textures, but some beautiful borders can be created with all one-color plants or with a target peak bloom time, such as spring.

The trick to designing a beautiful perennial border is to select plants that bloom at different times so you have something blooming throughout the growing season. This may take you a few seasons to master, but it is quite gratifying when it all comes together. Select a mix of early, mid-, and late bloomers that match your soil and sunlight conditions.

With a little planning, your perennial border can have something going on from early spring through fall, as in this garden, which includes coneflower, rudbeckia, astilbe, and violas.

Comprising common but beautiful perennial plants, the border garden seen here frames the relaxing lawn nicely. Included in the garden are iris, hosta, daylily, and daisy.

Planting Perennials

Most perennials are best planted in spring so they have an entire growing season to develop roots and become established before they have to face winter. Rainfall is also usually more abundant in spring. But container-grown plants can be planted almost any time during the growing season, as long as you can provide them with adequate moisture. If you plant in the heat of summer, you may need to provide some type of shading until the plants become established. Fall planting should be finished at least 6 weeks before hard-freezing weather occurs. Early spring is a good time to plant perennials in colder climates.

Plant spacing depends on each individual species and how long you want to wait for your garden to fill in, but generally about 12 inches is good for most herbaceous perennial plants. Obviously the more plants you can afford the sooner your garden will be more attractive and the fewer weed problems you will have. However, planting too densely can be a waste of money and effort.

Good soil preparation is extremely important for perennials, since they may be in place for many years. Dig the bed to a depth of 8 to 10 inches and work in at least 2 inches of organic matter before planting.

A cottage garden is a charming way to incorporate perennials into a landscape. It typically has a looser, more relaxed style and usually includes a lot of old-fashioned and fragrant flowers. It is a good style for people who like to have a lot of different plants.

Select a variety of perennials with varying bloom times, flower colors, and plant heights, as well as a few plants with interesting foliage to fill in.

How to Plant Perennials

How to Plant Perennials

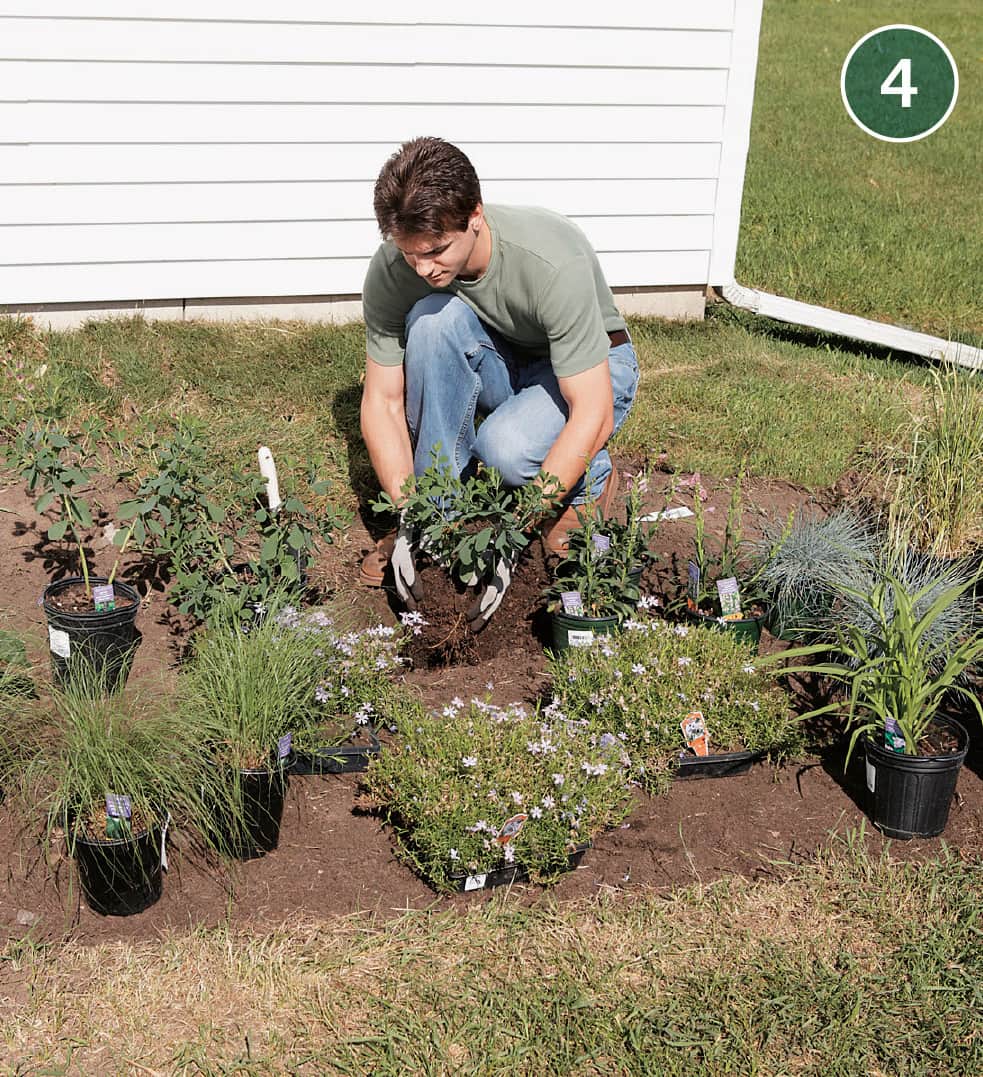

Before removing plants from their containers, place them in the prepared garden to see how they will look together. Experiment with different groupings until you find an arrangement that pleases you.

Dig a hole about twice as wide as each container and deep enough so the plant is just a little higher than it was in the container, to allow for soil settling. Dig holes one at a time to make it easier to maintain the arrangement.

Gently remove the plant from its container and pull apart any circling roots. Fill in with soil and tamp it around the plant.

Water the entire garden thoroughly to settle the soil around the roots. Make sure the plants get plenty of water until they are established.

TIP: Create a shallow well ringing around the base of the stem to trap water so it doesn’t run off as quickly.

Creating a New Garden Bed

Chances are there is already something growing where you want to install your new garden. And chances are it’s not desirable vegetation. As tempting as it is, do not just jump right in and start planting, figuring it will be easy to just pull the weeds as you go. Proper site preparation is the key to success. Take the time to get rid of existing vegetation and improve the soil before you start putting plants in the ground. This preparation will pay significant dividends.

How to Create a New Garden Bed

How to Create a New Garden Bed

Use a sun-warmed garden hose to lay out your proposed garden, following the topography of the site. Most gardens look best with gentle curves rather than straight lines.

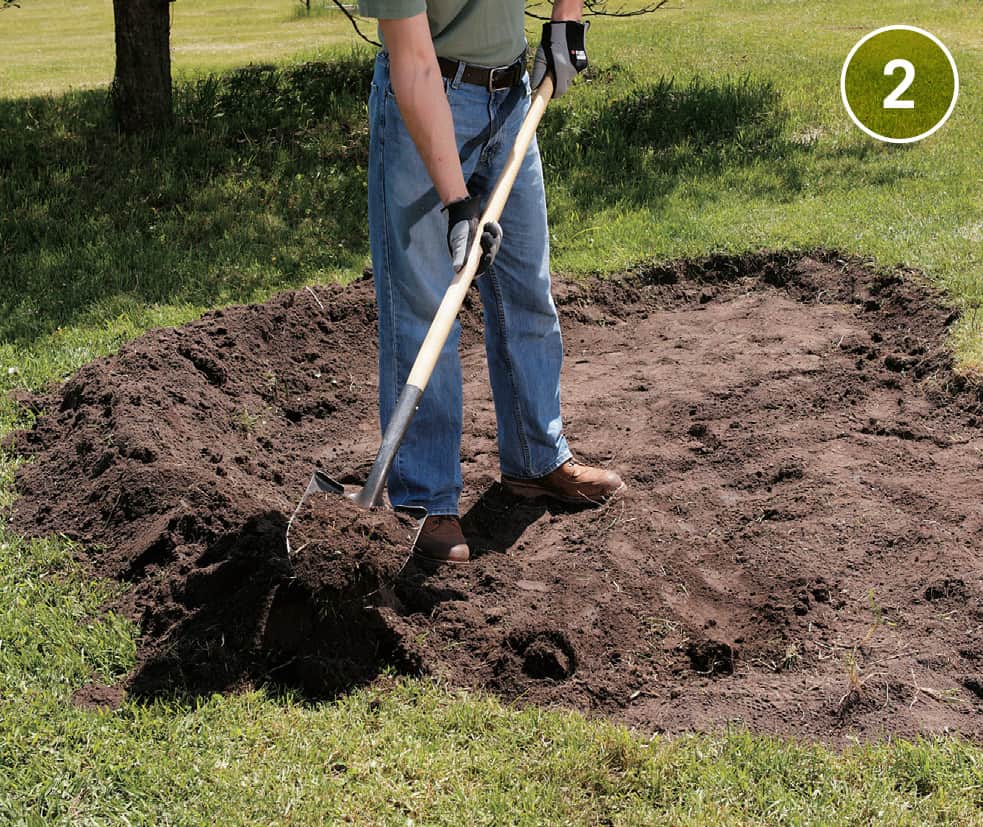

Remove existing vegetation. There are several ways to get rid of existing vegetation. Which way you choose depends on how much time you have and how you feel about using herbicides. The most natural way to create a new garden bed is to dig it up manually. Just be sure to get rid of all the existing plant roots. Even tiny pieces of tough perennial-weed roots can grow into big bad weeds in no time. A major disadvantage with this method is that you lose substantial amounts of topsoil. To avoid this, if you have the time, you can simply turn the sod over and allow it to decay on site. This will take at least one growing season.

Once the existing vegetation is dead or removed, turn the soil by hand or with a tiller, and add soil amendments. Do not use a tiller without killing all existing vegetation first—it may look like you’ve created a bare planting area, but all you’ve done is ground the roots into smaller pieces that will sprout into more plants than you started with. Even after multiple tillings spaced weeks apart, you’ll be haunted by these root pieces.

Install landscape edging to keep lawn grasses from invading your garden. The best option is to install a barrier of some type. When it comes to barriers, it’s worth paying more for a quality material. Metal edging buried 4" or more into the soil effectively keeps turf from sneaking in. If you go with black plastic edging, use contractor grade to avoid having to replace it in a few years.

Cover the new garden with mulch. Mulching your new garden will not only help keep the weeds from settling in, it will also help maintain soil moisture and prevent the soil from washing away until you can get the plants established. Cover the entire prepared garden bed with 2" to 3" of an organic mulch such as shredded bark, pine bark nuggets, cocoa bean hulls, or shredded leaves. Avoid using grass clippings; they tend to mat down and become smelly.

Concrete Curb Edging

Poured concrete edging is perfect for curves and custom shapes, especially when you want a continuous border at a consistent height. Keeping the edging low to the ground (about 1 inch above grade) makes it work well as a mowing strip, in addition to a patio or walkway border. Use fiber-reinforced concrete mix, and cut control joints into the edging to help control cracking.

Concrete edging draws a sleek, smooth line between surfaces in your yard and is especially effective for curving paths and walkways.

How to Install Concrete Curb Edging

How to Install Concrete Curb Edging

Lay out the contours of the edging using a rope or garden hose. For straight runs, use stakes and mason’s string to mark the layout. Make the curb at least 5" wide.

Dig a trench between the layout lines 8" wide (or 3" wider than the finished curb width) at a depth that allows for a 4"-thick (minimum) curb at the desired height above grade. Compact the soil to form a flat, solid base.

Stake along the edges of the trench, using 1" × 1" × 12" wood stakes. Drive a stake every 18" along each side edge.

Build the form sides by fastening 4"-wide strips of 1/4" hardboard to the insides of the stakes using 1" wood screws. Bend the strips to follow the desired contours.

Add spacers inside the form to maintain a consistent width. Cut the spacers from 1 × 1 to fit snugly inside the form. Set the spacers along the bottom edges of the form at 3-ft. intervals.

Fill the form with concrete mixed to a firm, workable consistency. Use a margin trowel to spread and consolidate the concrete.

Tool the concrete: once the bleed water disappears, smooth the surface with a wood float. Using a margin trowel, cut 1"-deep control joints across the width of the curb at 3-ft. intervals. Tool the side edges of the curb with an edger. Allow to cure. Seal the concrete, as directed, with an acrylic concrete sealer, and let it cure for 3 to 5 days before removing the form.

Mulching Beds

Mulch is the dressing on a landscape bed, but its benefits run deeper than surface appeal. Mulch protects plant and tree roots, prevents soil erosion, discourages weed growth, and helps the ground retain moisture. You can purchase a variety of mulches for different purposes. Synthetic mulches and stones are long-lasting, colorful, and resist erosion. They’ll never break down. Organic mulches, such as compost and wood chips, enrich soil and double as “dressing” and healthy soil amendments.

No matter what type of mulch you choose, application technique is critical. If you spread it too thick it may become matted down and can trap too much moisture. Too thin, it can wash away to reveal bare spots. If it is unevenly applied, it will appear spotty.

Consider timing before you apply mulch. The best time to mulch is mid- to late-spring, after the ground warms up. If you apply mulch too soon, the ground will take longer to warm up and your plants will suffer for it. You may add more mulch during the summer to retain water, and in the winter to insulate soil. (As weather warms, lift some of the mulch to allow new growth to sprout.) Spring is prime mulching time.

Mulch comes in many varieties, but most is made from shredded wood and bark. Because it is an organic material, it breaks down and requires regular refreshing.

How to Landscape with Mulch

How to Landscape with Mulch

Remove weeds from the bed and water plants thoroughly before applying mulch. For ornamental planting beds it often is a good idea to lay strips of landscape fabric over the soil before mulching.

Working in sections, scoop a pile of material from the load (wheelbarrow or bag) and place the piles around the landscape bed.

Spread mulch material to a uniform 1" thickness to start. Do not allow mulch to touch tree trunks or stems of woody ornamentals. Compost can double as mulch and a soil amendment that provides soil with nutrients. If you don’t make your own compost, you can purchase all-natural products such as Sweet Peet.

Rain Garden

A rain garden collects and filters water runoff, which prevents flooding and protects the environment from pollutants carried by urban stormwater. Rain gardens provide a valuable habitat for birds and wildlife, and these purposeful landscape features also enhance the appearance of your yard. In fact, when a rain garden is installed and planted properly, it looks like any other landscape bed on a property. (There are no ponds or puddles involved.) The difference is, a rain garden can allow about 30 percent more water to soak into the ground than a conventional lawn.

Though a rain garden may seem like a small environmental contribution toward a mammoth effort to clean up our water supply and preserve aquifers, collectively they can produce significant community benefits. For instance, if homeowners in a subdivision each decide to build a rain garden, the neighborhood could avoid installing an unsightly retention pond to collect stormwater runoff. So you see, the little steps you take at home can make a big difference.

Most of the work of building a rain garden is planning and digging. If you recruit some helpers for the manual labor, you can easily accomplish this project in a weekend. As for the planning, give yourself good time to establish a well-thought-out design that considers the variables mentioned here. And as always, before breaking ground, you should contact your local utility company or digging hotline to be sure your site is safe.

Preparing the Land

Soil is a key factor in the success of your rain garden because it acts as a sponge to soak up water that would otherwise run off and contribute to flooding, or cause puddling in a landscape. Soil is either sandy, silty, or clay based, so check your yard to determine what category describes your property. Sandy soil is ideal for drainage, while clay soils are sticky and clumpy. Water doesn’t easily penetrate thick, compacted clay soils, so these soils need to be amended to aerate the soil body and give it a porous texture that’s more welcoming to water runoff. Silty soils are smooth but not sticky and absorb water relatively well, though they also require amending. Really, no soil is perfect, so you can plan on boosting its rain garden potential with soil amendments. The ideal soil amendment is comprised of: washed sharp sand (50 percent); double-shredded hardwood mulch (15 percent); topsoil (30 percent); and peat moss (5 percent). Compost can be substituted for peat moss.

While planning your rain garden, give careful consideration to its position, depth, and shape. Build it at least 10 feet from the house, and not directly over a septic system. Avoid wet patches where infiltration is low. Shoot for areas with full or partial sun that will help dry up the land, and stay away from large trees. The flatter the ground, the better. Ideally, the slope should be less than a 12 percent grade.

Residential rain gardens can range from 100 to 300 square feet in size, and they can be much smaller, though you will have less of an opportunity to embellish the garden with a variety of plants. Rain gardens function well when shaped like a crescent, kidney, or teardrop. The slope of the area where you’re installing the rain garden will determine how deep you need to dig. Ideally, dig 4 to 8 inches deep. If the garden is too shallow, you’ll need more square footage to capture the water runoff, or risk overflow. If the garden is too deep, water may collect and look like a pond. That’s not the goal.

Finally, as you consider the ideal spot for your rain garden—and you may find that you need more than one—think about areas of your yard that you want to enhance with landscaping. Rain gardens are aesthetically pleasing, and you’ll want to enjoy all the hard work you put into preparing the land and planting annuals and perennials.

How to Build a Rain Garden

How to Build a Rain Garden

Choose a site, size, and shape for the rain garden, following the design standards outlined on the previous two pages. Use rope or a hose to outline the rain garden excavation area. Avoid trees and be sure to stay at least 10 ft. away from permanent structures. Try to choose one of the recommended shapes: crescent, kidney, or teardrop.

Dig around the perimeter of the rain garden and then excavate the central area to a depth of 4" to 8". Heap excavated soil around the garden edges to create a berm on the three sides that are not at the entry point. This allows the rain garden to hold water in during a storm.

Dig and fill sections of the rain garden that are lower, working to create a level foundation. Tamp the top of the berm so it will stand up to water flow. The berm eventually can be planted with grasses or covered with mulch.

Level the center of the rain garden and check with a long board with a carpenter’s level on top. Fill in low areas with soil and dig out high areas. Move the board to different places to check the entire garden for level.

NOTE: If the terrain demands, a slope of up to 12 percent is okay. Then, rake the soil smooth.

Plant specimens that are native to your region and have a well-established root system. Contact a local university extension or nursery to learn which plants can survive in a saturated environment (inside the rain garden). Group together bunches of three to seven plants of like variety for visual impact. Mix plants of different heights, shapes, and textures to give the garden dimension. Mix sedges, rushes, and native grasses with flowering varieties. The plants and soil cleanse stormwater that runs into the garden, leaving pure water to soak slowly back into the earth.

Apply double-shredded mulch over the bed, avoiding crowns of new transplants. Mulching is not necessary after the second growing season. Complement the design with natural stone, a garden bench with a path leading to it, or an ornamental fence or garden wall. Water a newly established rain garden during drought times—as a general rule, plants need 1" of water per week. After plants are established, you should not have to water the garden. Maintenance requirements include minor weeding and cutting back dead or unruly plant material annually.

Xeriscape

Xeriscaping, in a nutshell, is waterwise gardening. It is a form of landscaping using drought-tolerant plants and grasses. How a property is designed, planted, and maintained can drastically reduce water usage if xeriscape is put into practice. Some think that xeriscaping will become a new standard in gardening as water becomes a more precious commodity and as homeowners’ concern for the environment elevates.

Several misconceptions about xeriscaping still exist. Many people associate it with desert cactus and dirt, sparsely placed succulents and rocks. They are convinced that turf is a four-letter word and grass is far too thirsty for xeriscaping. This is not true. You can certainly include grass in a xeriscape plan, but the key is to incorporate turf where it makes the most sense: children’s play areas or front yards protected from foot traffic. Also, your choice of plants expands far beyond prickly cactus. The plant list, depending on where you live, is long and varied.

Xeriscaping is associated with sand, cacti, and arid climates, but the basic idea of planting flora that withstands dry conditions and makes few demands on water resources is a valid goal in any area.

The Seven Principles of Xeriscape

Keep in mind these foundational principles of xeriscape as you plan a landscape design. First begin by finding out what the annual rainfall is in your area. What time of year does it usually rain? Answering these questions will help guide plant selection. Now look at the mirco-environment: your property. Where are there spots of sun and shade? Are there places where water naturally collects and the ground is boggy? What about dry spots where plant life can’t survive? Where are trees, structures (your home), patios, walkways, and play areas placed? Sketch your property and figure these variables into your xeriscape design.

Also, carefully study these seven principles and work them into your plan.

1. Water conservation: Group plants with similar watering needs together for the most efficient water use. Incorporate larger plantings that provide natural heating and cooling opportunities for adjacent buildings. If erosion is a problem, build terraces to control water runoff. Before making any decision, ask yourself: how will this impact water consumption?

2. Soil improvement: By increasing organic matter in your soil and keeping it well aerated, you provide a hardy growing environment for plants, reducing the need for excess watering. Aim for soil that drains well and maintains moisture effectively. Find out your soil pH level by sending a sample away to a university extension or purchasing a home kit. This way, you can properly amend soil that is too acidic or alkaline.

3. Limited turf areas: Grass isn’t a no-no, but planting green acres with no purpose is a waste. The typical American lawn is not water-friendly—just think how many people struggle to keep their lawns green during hot summers. If you choose turf, ask a nursery for water-saving species adapted to your area.

4. Appropriate plants: Native plants take less work and less water to thrive. In general, drought-resistant plants have leaves that are small, thick, glossy, silver-gray, or fuzzy. These attributes help plants retain water. As a rule, hot, dry areas with south and west exposure like drought-tolerant plants; while north- and east-facing slopes and walls provide moisture for plants that need a drink more regularly. Always consider a plant’s water requirements and place those with similar needs together.

5. Mulch: Soil maintains moisture more effectively when its surface is covered with mulch such as leaves, coarse compost, pine needles, wood chips, bark, or gravel. Mulch will prevent weed growth and reduce watering needs when it is spread 3 inches thick.

6. Smart irrigation: If you must irrigate, use soaker hoses or drip irrigation (see page 43). These systems deposit water directly at plants’ roots, minimizing runoff and waste. The best time to water is early morning.

7. Maintenance: Sorry, there’s no such thing as a no-maintenance lawn. But you can drastically cut your outdoor labor hours with xeriscape. Just stick to these principles and consider these additional tips: 1) plant windbreaks to keep soil from drying out (see page 38); 2) if possible, install mature plants that require less water than young ones; 3) try “cycle” irrigation where you water to the point of seeing runoff, then pause so the soil can soak up the moisture before beginning to water again.

How to Xeriscape Your Yard

How to Xeriscape Your Yard

Plan the landscape with minimal turf, grouping together plants with similar water requirements. Refer to the Seven Principles of Xeriscape as you sketch (see page 59). Always consider your region’s climate and your property’s microclimate: rainfall, sunny areas, shady spots, wind exposure, slopes (causing run-off), and high foot-traffic zones.

Divide your xeriscape landscape plan into three zones. The oasis is closest to a large structure (your home) and can benefit from rain runoff and shade. The transition areas is a buffer between the oasis and arid zones. Arid zones are farthest away from structures and get the most sunlight. These conditions will dictate the native plants you choose.

Plant in receding layers by installing focal-point plants closest to the home (or any other structure), choosing species that are native to the area. As you get farther away from the home, plant more subtle varieties that are more drought tolerant.

As you plant beds, be sure to group together plants that require more water so you can efficiently water these spaces.

Incorporate groundcover on slopes, narrow strips that are difficult to irrigate and mow, and shady areas where turf does not thrive. Install hardscape such as walkways, patios, and steppingstone paths in high foot-traffic zones.

Mulch will help retain moisture, reduce erosion, and serves as a pesticide-free weed control. Use it to protect plant beds and fill in areas where turf will not grow.

Plant turf sparingly in areas that are easy to maintain and will not require extra watering. Choose low-water-use grasses adapted for your region. These may include Kentucky Bluegrass, Zoysia, St. Augustine, and Buffalo grass.

Zen Garden

What’s commonly called a Zen garden in the West is actually a Japanese dry garden, with little historical connection to Zen Buddhism. The form typically consists of sparse, carefully positioned stones in a meticulously raked bed of coarse sand or fine gravel. Japanese dry gardens can be immensely satisfying. Proponents find the uncluttered space calming and the act of raking out waterlike ripples in the gravel soothing and perhaps even healing. The fact that they are low maintenance and drought resistant is another advantage.

Site your garden on flat or barely sloped ground away from messy trees and shrubs (and cats), as gravel and sand are eventually spoiled by the accumulation of organic matter. There are many materials you can use as the rakable medium for the garden. Generally, lighter-colored, very coarse sand is preferred—it needs to be small enough to be raked into rills yet large enough that the rake lines don’t settle out immediately. Crushed granite is a viable medium. Another option that is used occasionally is turkey grit, a fine gravel available from farm supply outlets. In this project, we show you how to edge your garden with cast pavers set on edge, although you may prefer to use natural stone blocks or even smooth stones in a range of 4 to 6 inches.

A Zen garden is a small rock garden, typically featuring a few large specimen stones inset into a bed of gravel. It gets its name from the meditative benefits of raking the gravel.

How to Make a Zen Garden

How to Make a Zen Garden

Lay out the garden location using stakes and string or hoses and then mark the outline directly onto the ground with landscape paint.

Excavate the site and install any large specimen stones that require burial more than 1/2 ft. below grade.

Dig a trench around the border for the border stones, and lay down landscape fabric.

Pour a 3" thick layer of compactable gravel into the border trench and tamp down with a post or a hand tamper.

Place border blocks into the trench and adjust them so the tops are even.

Test different configurations of rocks in the garden to find an arrangement you like. If it’s a larger garden, strategically place a few flat rocks so you can reach the entire garden with a rake without stepping in the raking medium.

Set the stones in position on individual beds of sand about 1" thick. Pour in pebbles.

Rake the medium into pleasing patterns with a special rake (see next page).

TOOLS & MATERIALS

TOOLS & MATERIALS SHRUB PRUNING

SHRUB PRUNING

HEDGE TRIMMERS

HEDGE TRIMMERS