THE SIX chapters of

group 3, “Regulatory Principles,” prescribe regulations that the ruler should implement in governing his realm and managing his bureaucracy, specifically the changes that the founding ruler of a new dynasty should make to show that he has been invested with the Mandate of Heaven. They cover a wide range of issues, from ritual matters such as the proper day for the start of the civil calendar year and the color of court vestments, to administrative issues such as determining (on numerological grounds) the number of officials in various positions and how they should be selected, to hierarchical considerations such as regulations for the appropriate clothing for people of different ranks of society and how much wealth each rank should enjoy.

GROUP 3: REGULATORY PRINCIPLES, CHAPTERS 23–28

23. 三代改制質文 San dai gai zhi zhi wen The Three Dynasties’ Alternating Regulations of Simplicity and Refinement

24. 官制象天 Guan zhi xiang tian Regulations on Officialdom Reflect Heaven

25. 堯舜不擅移湯武不專殺 Yao Shun bu shan yi; Tang Wu bu zhuan sha Yao and Shun Did Not Presumptuously Transfer [the Throne]; Tang and Wu Did Not Rebelliously Murder [Their Rulers]

26. 服制 Fu zhi Regulations on Dress

27. 制度 Zhi du Regulating Limits

28. 爵國 Jue guo Ranking States

Description of Individual Chapters

Chapter 23, “The Three Dynasties’ Alternating Regulations of Simplicity and Refinement,” is extremely long.

1 It contains the

Chunqiu fanlu’s most elaborate and complex discussions of the regulations that a dynastic founder should follow at the beginning of his reign. Adopting a question-and-answer format—a literary device commonly found in Western Han writings—it describes a series of specific ritual regulations to be observed by the ruler upon receiving the Mandate of Heaven. The regulations are determined by correlating the current dynasty with a number of different historical cycles and numerological schemes identified as the “Three Sequences” (

san tong 三統), “Three Rectifications” (

san zheng 三正), “Five Inceptions” (

wu duan 五端), and “Four Models” (

si fa 四法). We have divided the chapter into sixteen sections, each either containing one question and its response or following some other perceptible break in the chapter’s content.

The chapter begins in section 23.1 on an ostensibly simple note, with a canonical reference to the first entry in the

Spring and Autumn and its corresponding

Gongyang explanation: “The

Spring and Autumn states: ‘The king’s first month.’ The [

Gongyang]

Commentary states: ‘To whom does “the king” refer? It refers to King Wen. Why [does the

Spring and Autumn] first mention “the king” and then mention “the first month”?’ The king rectified the month.”

2 The sense of this passage depends on a play on words. As a noun phrase,

zheng yue 正月 means “the first month,” but as a verb–noun construction, it means “to rectify the month.” This introduces the main point of this whole long, multisectioned chapter: that the founding king of a new dynasty makes many ritual changes, including designating a new first month to begin the civil calendar, to demonstrate that he is the new holder of the Mandate of Heaven. In this case, we are told that the king is King Wen, founder of the Zhou dynasty, and that he “rectified” the month (that is, he designated a new first month of the civil calendar) at the beginning of his reign as the Son of Heaven.

In section 23.2, the simple formulaic expression “the king’s first month” canonically justifies the chapter’s subsequent prescriptions for a dynastic founder to change such symbolic hallmarks of his dynasty as the calendar, the color of the court dress, the music to be composed or performed at court, and the rituals to be observed. All these changes unite the empire and demonstrate that the surname of the ruling household has been changed and that the founder of the new dynasty has not displaced a legitimate sovereign but has received the Mandate of Heaven. The ruler thus creates specific categories to venerate Heaven.

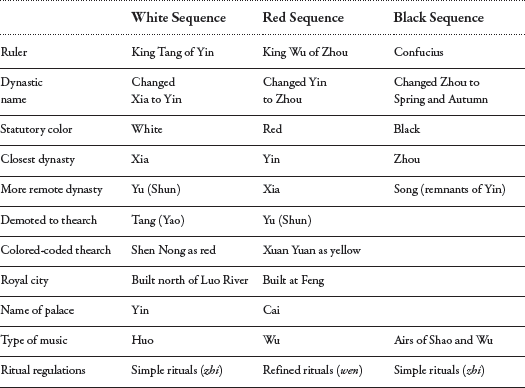

After this opening reference to the canon, section 23.3 raises a question that moves the discussion into more elaborate theoretical territory: How precisely does the ruler “revise regulations and create benchmarks”? He must look back to preceding dynasties to match his own regulations with the appropriate sequences, designated by cycles of three, four, and five. The Three Sequences are symbolized by the three colors white, red, and black and are exemplified by the three rulers King Tang of the Shang, King Wu of the Zhou, and the “New King” or “New Royal Dynasty” (

xin wang 新王) of the

Spring and Autumn. It is interesting that here the Zhou dynasty is considered to have become defunct at the end of what we know as the Western Zhou period and that the Spring and Autumn period is regarded as a new dynasty that, given the overall political-historical stance of the

Chunqiu fanlu, we may identify with Confucius, the “uncrowned king.” The reigns of these dynastic founders are correlated with colors, as shown in

table 1.

Section 23.4 summarizes and extends this discussion, emphasizing the Three Rectifications (which seems to be another name for the Three Sequences) to determine the first month of the civil calendar and the appropriate color and directional correlates following from that. The sequence begins with black, continues with white and then red, and then repeats the sequence. Black begins the year with the month

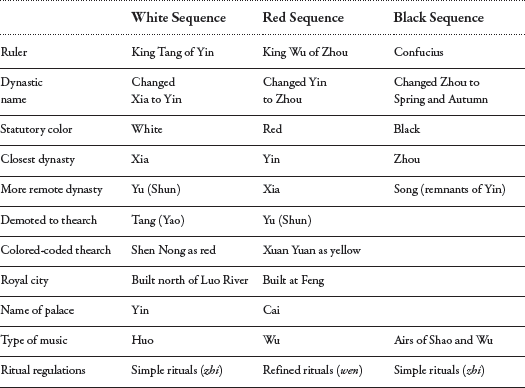

yin (the third astronomical month) in the east-northeast, to which the handle of the Northern Dipper points; the sun and the (new) moon are in the lunar lodge Encampment.

3 White begins the year with the month

chou (the second astronomical month) in the north-northeast, to which the handle of the Northern Dipper points; the sun and the (new) moon are in the lunar lodge Emptiness. Red begins the year with the month

zi (the first astronomical month) in the north, to which the handle of the Northern Dipper points; the sun and the (new) moon are in the lunar lodge Ox Leader. The relevant dynasties again are taken to be Shang, Zhou, and the “New Royal Dynasty” of the

Spring and Autumn; the regulations for each are shown in

table 2.

TABLE 1

The description of the Three Sequences and their respective Three Rectifications concludes with some interesting recommendations. It contends that the ancient rulers enacted these reforms at the beginning of their reigns upon receiving the Mandate and that they performed the Suburban Sacrifice with the express intention “to announce [the accession of the new dynasty] to Heaven, Earth, and the numerous spirits.” Having performed this sacrifice, they presented offerings to their distant and recent ancestors and then proclaimed their accession throughout the empire: “The Lords of the Land received [the proclamation of the new statutory color and beginning of the civil year] in their ancestral temples. They then announced it to their spirits of the land and grain, to the ancestors, and to the spirits of mountains and streams in their respective territories. Only then were the movements and responses of the various officials united.”

4TABLE 2

The next section, 23.5, begins by linking the Three Sequences to a concept designated as the Five Inceptions. The Five Inceptions are associated with the founders of the Three Dynasties (the Xia, Shang, and Zhou), in contrast to the Three Sequences, which are associated with the rulers of the Shang, Zhou, and the idealized dynasty of the uncrowned king envisioned in the Spring and Autumn. All are said to have unified the world by grasping the essentials of the Five Inceptions, which enabled them to rectify the regulations pertaining to court audiences so that each ranked participant, moving downward and outward from the center (Son of Heaven, Lords of the Land, great ministers and officials, neighboring tribes, and those from distant lands), donned clothing distinctive of their rank relative to that of the Son of Heaven.

Section 23.6 is a fragment that explores the implications of two meanings of the word zheng 正: “first” (as in “first month”) and “to rectify.” Section 23.7 then returns to the theme of 23.4, discussing in greater detail how the Spring and Autumn period corresponds to a “new royal dynasty” and thus requires the alteration of the (red) symbolic emblems of the preceding Zhou dynasty to correspond to the Black Sequence. This section also introduces more remote eras of dynastic history, specifying the proper titles of the predynastic rulers, dynastic kings, and their descendants, as well as the necessity of preserving their descendants by bestowing the appropriate territories on them.

The next few sections (23.8–23.14) consist of questions and answers on points raised earlier about how the

Spring and Autumn alters the titles of the preceding dynastic kings and predynastic thearchs so that each corresponds to a “new royal dynasty.” Returning to a point made in section 23.7, section 23.8 asks: If descendants of the former kings were called dukes, why does the

Spring and Autumn not follow this rule consistently, instead referring to the lord of Qii as a viscount in one instance and an earl in another? Section 23.9 explains why the Yellow Thearch stands at the head of the sequence of the Five Thearchs. Section 23.10 asks why, if “thearch” is an honorable designation, are the descendants of the “thearchs” given small states rather than large ones. This section introduces the principle guiding how descendants of the previous rulers are be treated. As they recede into the past, their noble titles move down the hierarchy (through seventeen steps: Three Royal Dynasties, Five Thearchs, and Nine Sovereigns), and their states grow smaller. Finally, they drop off the ladder of hierarchy altogether and revert to commoner status:

Therefore, even though they are eventually reduced to the status of commoner and are cut off from their territory, their positions in the ancestral temple and sacrificial offerings still are set forth in the liturgies of the Suburban Sacrifice, and they are honored at the sacrifice at Mount Tai. Thus it is said: “Reputation and name,

hun and

po, disperse into emptiness. Extreme longevity has no bounds.”

5

Section 23.10 also points out that in some cases, the Three Royal Dynasties leave unchanged the regulations of the preceding dynasty and, in others, revert to precedents from dynasties that are two, three, four, five, and nine cycles back. The next section, 23.11, asks why in certain respects the ruler should revert to the regulations of a previous dynasty after two cycles and in other respects he should revert after four. The answer to this question has been lost.

Section 23.12 explains that the “new royal dynasty” represented in the

Spring and Autumn had three grades of noble rank, in contrast to the Zhou, which had five grades. This section follows the

Gongyang Commentary in correlating the three grades with duke, marquis, and earl/viscount/baron. In contrast, section 23.13 associates the three grades with Heaven, Earth, and humankind.

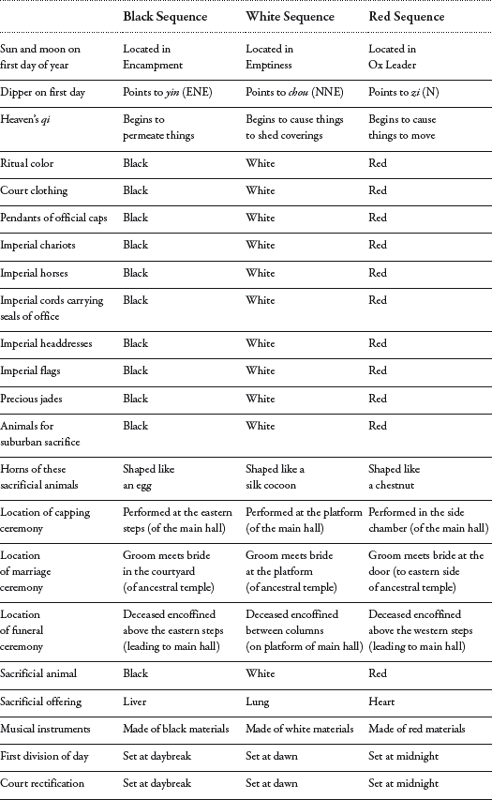

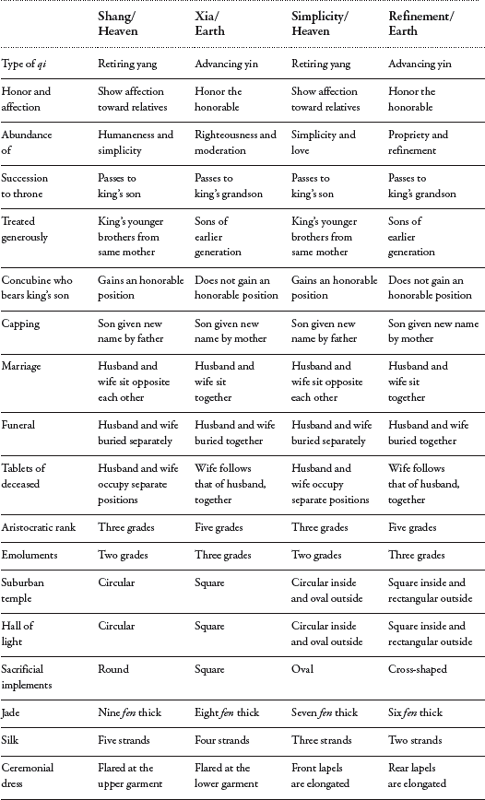

6Section 23.14 describes in great detail the correlation of the three grades with the Heaven, Earth, and humankind sequence. The resulting Four Models move through four archetypes of governance and then repeat.

1. Those who take Heaven as their support emulate Shang and rule as kings.

2. Those who take Earth as their support emulate Xia and rule as kings.

3. Those who take Heaven as their support emulate Simplicity and rule as kings.

4. Those who take Earth as their support emulate Refinement and rule as kings.

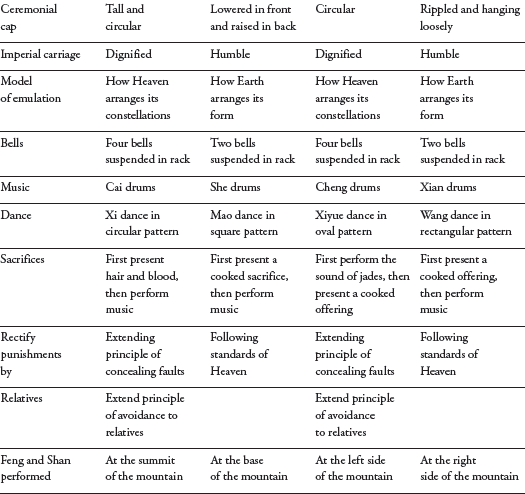

These four sequences correspond to the characteristics and regulations presented in

table 3.

Section 23.15 discusses the origins of the Four Models, tracing them to the era of the thearchs. This implies that they are more ancient than the Three Sequences observed by King Tang of the Shang and later exemplary rulers. In the Four Models scheme, Shun is identified with Heaven and Shang; Yu, with Earth and Xia; King Tang of the Shang, with Heaven and Simplicity; and King Wen of the Zhou, with Earth and Refinement. The attributes of each of these rulers are described to demonstrate how in turn they correlated with Heaven and Earth. Section 23.16 explains how the respective surnames of the ruling clans of these dynasties were selected.

Chapter 24, “Regulations on Officialdom Reflect Heaven,” contains five sections. We believe that the chapter originally consisted of the first section only and that the later sections originally were bits of commentary that at some point were erroneously incorporated into the chapter. We should point out that the text of section 24.1 in the

Chunqiu fanlu is identical to a passage in the “Kingly Regulations” of the

Classic of Rites.

7 It maintains that the bureaucracy of the Son of Heaven consisted of 120 offices, divided into four ranks, with each rank consisting of officials whose total number was a multiple of three: the three dukes, nine ministers, twenty-seven great officers, and eighty-one senior functionaries. It proposes that the former kings of antiquity employed regulations to ensure that the number and ranking of their offices and the selection of their officials accorded perfectly with the “great warp of Heaven.” Thus this ancient administration, with its numerology of fours and threes, was the perfect human image of Heaven’s annual course, mirroring Heaven’s four seasons, each consisting of three months: “According completely with Heaven’s numbers to assist in [the conduct of] human affairs signifies that government carefully attends to the Way. These 120 officials were the means by which the former kings conducted themselves in accordance with the correct Way.”

8 Just as the first, second, and third month of each of the four seasons has its distinctive characteristics, the upper, middle, and lower class of officials of each of the four tiers of officials has its distinctive qualities. Just as Heaven has its four permutations, human talent has its four selections: “The sagely person constitutes one selection; the noble person constitutes one selection; the good person constitutes one selection; [and] the upright person constitutes one selection.”

9 Section 24.1 concludes: “It is only the sage who can [similarly] fully utilize the permutations of humankind and harmonize them with those of Heaven, thereby establishing the affairs of the king.”

10 We believe that this concluding statement marks the end of the essay that originally constituted this chapter.

The next two sections, 24.2 and 24.3, are related commentarial intrusions that develop in new directions ideas put forth in the opening essay. Several features suggest that this is the case. First is the expression “What is meant by X (

he wei 何謂 X)?” This is a classic formulaic expression often used in commentaries to unpack a particularly recondite concept or develop a previously mentioned concept in new directions. Second, these sections contain repetitions, contradictions, and novelties not present in 24.1. Section 24.2 asks, “What is meant by ‘the great warp of Heaven’?” In 24.1, this expression was defined as a year of four seasons of three months apiece. In contrast, the expression here is defined as an elaborate numerology based on three and ten:

There are the three commencements [sunrise, noon, and sunset] that complete one day; the three days that complete a

gui [three-day period]; the three

xun [ten-day periods] that complete a month; the three months that complete a season; the three seasons that complete the achievements [of the year].

11 The cold, warm, and tepid are the three [types of temperature] that complete [the vitality of living] things. The sun, moon, and stars are the three [types of celestial bodies] that complete [the phenomenon of] light. Heaven, Earth, and humankind are the three [types of entities] that complete [the perfection of] virtue.

12

This list of examples demonstrates that “completing one with three” is emblematic of Heaven’s great warp. To create official regulations, then, the recommendation is to follow this one-to-three ratio for the four ranks of the bureaucracy. Accordingly, “three dukes constitute one selection; three ministers [for each duke] constitute one selection; three great officers [for each minister] constitute one selection; [and] three senior functionaries [for each great officer] constitute one selection.” Thus section 24.2 maintains the basic pattern of threes and fours seen in 24.1 but augments it with a numerology of three, four, twelve, and ten: “For this reason, taking three [men] to constitute a selection derives from Heaven’s warp; taking four to constitute a round [of selections] derives from Heaven’s seasons; taking twelve to constitute a cohort derives from the year’s measuring points; arriving at ten cohorts and stopping derives from Heaven’s starting points.”

13Building on this conclusion, section 24.3 asks, “What is meant by ‘Heaven’s starting points’?” The ten starting points of Heaven are Heaven, Earth, humankind, yin, yang, Fire, Metal, Wood, Water, and Earth. They constitute a cohort, and each cohort takes twelve officers at a time to correspond to the twelve months of the year. The text goes on to play with the numbers three, four, ten, and twelve, creating additional Heavenly correlations to arrive in various ways at the number 120. That this can be done in several different ways is taken as evidence for the correctness and numerological power of “Heaven’s numbers.”

Section 24.4 is a brief fragment of a numerological essay or passage of commentary that once again discusses Heaven’s numbers. Here the emphasis is on how human beings surpass all other living things in their ability to discover the significance of Heaven’s numbers. Using the kind of macrocosm/microcosm imagery found in many Han texts, it correlates three, four, and twelve, identified as the numbers of Heaven, with the human body and with the regulations of officialdom:

The body has four limbs, and each limb has three divisions. Three times four is twelve. When these twelve divisions support one another, the embodied form is established. Heaven has four seasons, and each season has three months. Three times four is twelve. When these twelve months receive one another, the yearly cycle is established. The officials have four selections, and each selection has its three men. Three times four is twelve. When these twelve officers support one another, the tasks of government are implemented.

14

This brief statement concludes by urging the reader to examine the many and subtle human correspondences with Heaven.

Section 24.5 continues the Heavenly numerology of the preceding sections, expressed in its own arcane terminology. It discusses the annual cycle of the four seasons of three months each, and here the year is identified as a “pattern of Heaven and Earth,” encompassing “Heaven’s four selection times”—that is, seasons. The four selection times of Heaven—spring for Lesser Yang, summer for Greater Yang, autumn for Lesser Yin, and winter for Greater Yin—are further divided into beginning, middle, and ending periods (months). In accordance with this Heavenly sequence, the former kings established their four selections of officials. Nothing in this section is particularly new except for the special terminology that it employs; otherwise, it is not much more than a restatement of points already made in sections 24.2 through 24.4.

The title of

chapter 25, “Yao and Shun Did Not Presumptuously Transfer [the Throne]; Tang and Wu Did Not Rebelliously Murder [Their Rulers],” refers to two short sections that were likely combined in this chapter by the

Chunqiu fanlu’s compiler because both address the topic of dynastic change. Moreover, dynastic change is relevant to all the chapters in this group, as it is the momentous historical event that triggers the various regulatory reforms discussed in other chapters in this group. Here two theoretical positions concerning how dynastic succession occurs—the abdication of good rulers and the violent overthrow of evil rulers—are challenged on the grounds that rulership is ultimately bestowed by Heaven and not determined by men.

Section 25.1 takes up the dynastic succession of the two exemplary sage-kings of legendary antiquity, Yao and Shun, revered for giving priority to virtue over blood. Each passed over his own sons to bequeath the throne to the most virtuous man in the kingdom. The first section of this chapter challenges this interpretation. Taking as its point of departure the opening lines of the Classic of Filial Piety that equate serving one’s father with serving Heaven, the essay argues that Yao and Shun did not presume to transfer the throne to other men, but instead it was the work of Heaven.

Section 25.2 also addresses dynastic succession but uses King Tang and King Wu as the subject of discussion. The question is whether they established the Shang and Zhou dynasties by legitimate means—receiving the Mandate of Heaven—or by illegitimate means—committing regicide. The topic is addressed in a dialogue or debate between two unnamed parties. The reader apparently enters the debate in medias res, as the opening lines are responding to an assumed prior challenge to the view—explicitly identified as “Confucian”—that Tang and Wu were “the utmost worthies and greatest sages” in history:

They hold that [these men] perfected the Way, [comprehensively] investigated righteousness, and epitomized [moral] beauty. Thus they rank them equal to Yao and Shun, designate them “sage-kings,” and take them as their models of emulation. Now if you consider Tang and Wu to have been unrighteous, then, sir, which kings of what generations, would you designate as “righteous”?

15

The respondent, apparently baffled by the question and unable to answer, is immediately barraged with a second question that challenges him to respond: “If you do not know, do you mean that [all] those who have ruled have been unrighteous? Or do you mean that there have been righteous rulers but that you are not familiar with them?”

16 The respondent replies with the example of the Divine Farmer (Shen Nong). This is immediately challenged. The commencement of the Divine Farmer’s reign, the interlocutor points out, did not coincide with the beginning of the world; therefore, his reception of the Mandate of Heaven, like that of Tang and Wu, must have involved replacing a prior ruler. This action is further justified by means of several interrelated principles of the Mandate of Heaven. Heaven establishes kings not on behalf of rulers but on behalf of the people; “Therefore if his virtue is sufficient to bring security and happiness to the people, Heaven bestows [the Mandate] on him; if his evil is sufficient to injure and harm the people, Heaven withdraws [the Mandate] from him.”

17 This clearly indicates that neither the bestowal nor the withdrawal of the Mandate is permanent. The performance of the Suburban Sacrifice and the change in dynastic surname mark the transfer of power from one dynastic house to another and underscore the critical fact that rulership is, as in the first argument of the chapter, ultimately a gift bestowed by Heaven, not a political prerogative transmitted from one man to another. Thus in every case Tang and Wu, and the seventy-two later kings who also chastised the unrighteous, simply punished those from whom Heaven had already withdrawn the Mandate. They did not commit regicide.

18These principles, the argument continues, have existed for eternity. If one condemns Tang and Wu for attacking Jie and Djou, then the Han conquest of Qin is to be condemned equally. Those who use these arguments do not understand Heaven’s principles or understand the

Gongyang principle of concealment: “It is a matter of propriety that a son conceals his father’s evil. Now if you were ordered to chastise others and you believed [the order] to be unrighteous, then you ought to conceal it for the sake of your state. How could it be appropriate [to use the order] to slander [your state]? This is what we call ‘With one statement, two errors.’”

19 Moreover, having lost the allegiance of their people, Jie and Djou no were longer kings in the true sense of the word. Thus executing them could not be regicide.

Chapter 26, “Regulations on Dress,” deals with sumptuary regulations: “Let clothing be regulated according to gradations in rank. Let wealth be spent according to gradations in salaries.”

20 The scope of the chapter is greater than that suggested by its title. Regulations are proposed not only for clothing but also for buildings, domesticated animals, retainers, boats and vehicles, and armor and weapons and not only for the living; mortuary items for the dead are included as well. The chapter concludes with a catalog of sumptuary regulations for various social ranks, from the Son of Heaven down to the lowest echelons of society: artisans, merchants, traders, and criminals.

Chapter 27, “ “Regulating Limits,” consists of five sections, all of which appear to have been included in this chapter because they embrace the notion that sage-rulers must establish regulations in order to maintain social order. Section 27.1 begins by quoting a well-known teaching attributed to Confucius: “Do not worry about poverty; worry about inequality.”

21 The text then explains that excesses of either poverty or wealth give rise to the most extreme of human emotions, desperation and haughtiness, which, in turn, give rise to two of the greatest social ills: thievery and violence. The sage consequently creates regulations to limit the extremes of wealth and poverty to enable rich and poor to live peacefully with each other and to enable the ruler to govern with ease. The current state of affairs is quite different, however:

The present age has abandoned regulations [that set] limits so that each person indulges his or her desires. When desires have no limits, then the vulgar act without restraint. When this tendency persists without end, the powerful people worry over insufficiencies above; the little people fear starvation below. Thus the wealthy increasingly covet profit and cannot act righteously; the poor daily disobey prohibitions and cannot be stopped. This is why the present age is difficult to govern.

22

The next section, 27.2, consists of a statement attributed to Confucius and two citations from the

Odes, all of which advocate setting limits on the material benefits enjoyed by the wealthy and powerful so that something is left for the weaker members of society, such as commoners and widows. This is the canonical basis for the conduct of the nobleman: “Therefore when the gentleman serves in office, he does not farm; when he farms, he does not fish; he eats what is in season and does not strive for delicacies.”

23 The section closes with a rebuttal by an unnamed person who maintains that this principle is not sufficient to restrain the common people; they still will risk their lives competing for material benefits.

While section 27.1 argues that the sage sets limits based on people’s emotional responses, and 27.2 justifies them on the basis of treating the common people fairly (backed by the authority of Confucius), section 27.3 argues that the sage looks to Heaven when creating regulations and limits. It quotes what may have been a popular proverb of the time: “Heaven does not bestow things in duplicate; what has horns is not permitted to have upper [incisor] teeth.

24 Therefore those who already possess what is great cannot possess what is small.”

25Section 27.4 observes that one characteristic of sages is their capacity for forethought. The sage eliminates deceptively insignificant and trivial affairs by guarding against them early on, in the same way that levees and dikes guard against floods. Thus he “promulgates regulations and limits; he promulgates ritual restrictions.” This claim is supported by a closing citation from the Documents proposing that if the ruler pays attention to the status markers of the nobility, they will respond with reverence.

Section 27.5 turns to the ways in which regulations that set limits affect sumptuary laws. Simple clothing was first created to satisfy the physical needs of humans, to protect their bodies from the elements. But once people began to dye and ornament clothing, it became a means to order society hierarchically. Different colors and types of decoration illuminated the distinction between superior and inferior so that social order could be maintained. But if sumptuary regulations are not promulgated and enforced, the text warns, chaos will ensue. The section concludes with a brief reference to the different garments worn by the various ranks of society in ancient times: the Son of Heaven, the Lords of the Land, the great officers, and the common folk.

Chapter 28, “Ranking States,” is a long chapter that we have divided into eight sections (the last of which is divided into five subsections). The chapter falls neatly into two parts: the first made up of sections 28.1 to 28.7, and the second, subsections 28.8A through 28.8E. Both parts outline idealized schemes of administrative organization, both of which differ markedly from those proposed in

chapter 24, “Regulations on Officialdom Reflect Heaven.”

26 The titles of officials, their numbers, and their ranks are not the same in these two chapters. In

chapter 24, the idealized bureaucracy derives its justification from Heaven, and the rank and number of its officials are patterned on Heaven’s annual cycle. But in

chapter 28, the idealized bureaucracy is based on the authority of the

Spring and Autumn read through the filter of the

Gongyang Commentary. It describes the bureaucracy of the Son of Heaven, as in

chapter 24, as well as the administrations of different types of states, described as large, small, and dependent. It also touches on a range of topics not addressed in

chapter 24.

Section 28.1 compares the Zhou dynasty and the era of the

Spring and Autumn. The five-grade ranking system of the Zhou (duke, marquis, earl, viscount, baron), with its three classes of officers, is seen as an expression of the emphasis on outer refinement that is said to have characterized the Zhou. The ranking system of the

Spring and Autumn is quite different. The three dukes of the Son of Heaven and the king’s descendants designated as dukes comprise one grade; rulers of large states designated as marquises comprise one grade; and rulers of small states designated as earls, viscounts, and barons combine to comprise one grade. The system thus has three grades and two classes of officers, which is seen as an expression of the Spring and Autumn “dynasty’s” emphasis on inner simplicity. This alternating scheme of inner simplicity and outer refinement is mentioned in Dong’s memorials, a point to which we will return in our discussion of issues of dating and attribution. Section 28.2 specifies the terminology used in the

Spring and Autumn to refer to the four grades of dependent states. Section 28.3 specifies the size of the territories controlled by the Son of Heaven, dukes and marquises, earls, viscounts and barons, and various ranks of dependent states. They range from a realm one thousand

li square for the Son of Heaven to a realm ten

li square for the least of the dependent states.

27Section 28.4 describes the ranking system employed in the

Spring and Autumn to refer to nobles of various grades. There are five ranks below the Son of Heaven: the three dukes, great officer, junior great officer, functionary, and junior functionary. Section 28.5, interestingly, contends that the reference to five ranks in the previous section was in fact a criticism because it departed from the ancient practice of observing four ranks: senior minister, junior minister, senior functionary, and junior functionary. This section also shows how the

Spring and Autumn refers in comparative terms to high officials of states of various sizes, so that, for example, a great officer of a small state is referred to in the same terms as a junior minister of a middling state. Finally, it specifies the categorical rankings for officials with outstanding merit and virtue. Section 28.6 uses a macrocosm/microcosm argument to show how the grades and numbers of officials of the Son of Heaven and the Lords of the Land are modeled on Heaven. Section 28.7 deals in numerological terms with the “Three Armies” (the conventional term for the armed forces of a state), describing the number of conscripts enlisted by various levels of nobility and how the armies were supported. Sections 28.8A through 28.8E describe the size of territories allocated to the five grades of rulers (the Son of Heaven, dukes and marquises, earls, viscounts and barons, and dependent states), their associated land usage, armies, and populations; and the numbers, ranks, and salaries of their bureaucracies. These subsections repeat one another exactly, differing only in the rank of the various rulers and the numbers and grades appropriate to the administrations of each rank.

The first half of the chapter, sections 28.1 through 28.7, depicts the ranking system of this idealized empire by marshaling copious references to specific entries in the

Spring and Autumn followed by their attendant

Gongyang explications. The second half of the chapter, sections 28.8A through 28.8E, does not refer to the

Spring and Autumn in making its arguments. Instead, its ranking system clearly parallels the

Mencius and the “Royal Regulations” chapter of the

Classic of Rites and introduces some details not included in those sources. The two halves of

chapter 28 deal with idealized schemes of administrative organization but differ in important ways and probably originally were separate essays by different authors.

Issues of Dating and Attribution

Like other groups of chapters in the

Chunqiu fanlu and of the text overall,

group 3, “Regulatory Principles,” assembles different materials of diverse origins. Several of its chapters or chapter sections are likely to date from around the lifetime of Dong Zhongshu and may be his work, but other chapters are almost certainly by others.

Chapter 23, “The Three Dynasties’ Alternating Regulations of Simplicity and Refinement,” contains very disparate materials. Some of the chapter’s sections are very unlikely to have been written by Dong Zhongshu or anyone in his immediate circle, but Dong could plausibly have been the author of some of the other sections. As can be seen from our summary description, section 23.10 is a complex discussion of historical cycles based on numerological calculations involving the numbers two, three, four, five, and nine. The cycles in this section do not correspond to those described in the first group of

Chunqiu fanlu chapters (

group 1, “Exegetical Principles”) or in Dong’s memorials. On the contrary, in Dong Zhongshu’s third memorial to Emperor Wu and in the first group of

Chunqiu fanlu chapters, which contains the materials most closely associated with the historical Dong Zhongshu, he lays out a different theory of historical cycles. True, the concept of altering regulations upon the reception of the Mandate is discussed in chapter 1.5 and in Dong’s third memorial, but the details of those discussions differ markedly from those described in

chapter 23. Furthermore, writings dating to the reigns of Emperors Jing and Wu (when Dong Zhongshu flourished) do not generally trace the rulers of remote antiquity back beyond the Three Kings and Five Thearchs. Instead, the chapter’s reference to the Nine Sovereigns reflects the rhetoric of the era of Wang Mang or the early Eastern Han. The elaborate Red, White, and Black Sequences described in sections 23.3 and 23.4 are unlike anything found in the authentic writings of Dong Zhongshu. Although to some extent they reflect principles already in the “Yue ling” (Monthly Ordinances) calendars of the late Warring States period and early Han, as presented here they seem more like a reflection of the concerns of the Wang Mang interregnum and the Eastern Han period. To that extent, we agree with the Japanese scholar Harada Masaota, who concluded that these sections of

chapter 23 were not written by Dong and could not have been written earlier than the Eastern Han, based on their affinities with the

Bohutong and

Chunqiu Gongyang zhuan Heshi jiegu.28

The references to the

Spring and Autumn in sections 23.1 and 23.2 seem superficially not to be out of character for the genuine writings of Dong Zhongshu. But section 23.2 clearly advises making comprehensive changes in regulations at the founding of a dynasty, whereas in one of his memorials to Emperor Wu, Dong quotes Confucius as saying, “ ‘Was it not Shun who ruled by taking no action?’ He simply altered the first month of the year and changed the color of court dress to comply with the Mandate of Heaven, that’s all. In the remaining matters of governance, he completely followed the Way of Yao. Why would he have changed anything else?” But then Dong points out that dynastic founders did in fact make some changes in their predecessors’ practices while retaining others.

29 The emphasis in 23.13 on “simplicity and refinement” (which we find also in chapter 28.1) is consistent with Dong’s known opinions. In addition, the idea of Confucius as the “uncrowned king” of the Spring and Autumn period, reflected in section 23.7, was dear to Dong’s heart, as seen in one of his memorials to Emperor Wu:

When Confucius was writing the

Spring and Autumn, he entered the terms

zheng and

wang at the beginning of the first entry and related them to the myriad affairs of governance, thus revealing the writings of an uncrowned king. Viewed from this perspective, there is indeed only one thread binding together the thearchs and kings, yet the difference between toiling away and remaining idle is due to the different ages that rulers happen to live in. And so Confucius also said: “The

wu is the ultimate in beauty but not quite in goodness.” This is what he meant.

30

Thus we conclude that

chapter 23, not surprisingly, contains diverse materials of strikingly different date and authorship, only some sections of which could plausibly be regarded as the work of Dong Zhongshu or his immediate circle of disciples.

Like the numerology of section 23.10, the numerological description of the ideal bureaucracy found in

chapter 24 is uncharacteristic of the known works of Dong Zhongshu, though it was not necessarily written much later than his own lifetime. Similarly, the content of

chapter 25 also is not characteristic of Dong’s writings. In his comments at the close of

chapter 25, Su Yu, the Qing scholar and commentator of the

Chunqiu fanlu, states that this chapter could not have been written by Dong Zhongshu. He gives several reasons for his position. For example, he argues that even though Dong deeply despised the Qin, this chapter accepts that the Zhou dynasty was appropriately replaced by the Qin. When discussing punitive expeditions, scholars of the

Spring and Autumn always held up King Wen’s punishment (of Djou) for veneration and paired it with King Tang’s punishment (of Jie). Here, however, Kings Tang and Wu are cited together and compared with the Qin conquest of Zhou and the Han conquest of Qin. The “Biography of the Confucian Scholars” in the

Shiji records that Yuan Gu and Master Huang had a debate in front of Emperor Jing on the subject. It is possible that

chapter 25 preserves a longer portion of that debate, of which the

Shiji quotes only a small part. Su Yu concludes that the evidence dates the chapter to the reign of Emperor Jing but does not link it to Dong Zhongshu. We concur with this assessment.

Chapter 26 probably predates Dong but is compatible with his views:

Your servant has heard that sumptuary regulations and the ornamental black and yellow insignia were the means to distinguish the lofty from the base [and to] differentiate the noble from the mean in order to encourage the Virtuous. Thus in the

Spring and Autumn, the first things to be regulated by those who received Heaven’s Mandate were the change in the first month of the year and the alteration of the color of court dress to respond to Heaven. Nonetheless, the regulations concerning palaces and dwellings and flags and banners were as they were because they were based on particular models. Thus Confucius said: “Extravagance leads to insubordination; frugality leads to stubbornness.”

31 Frugality is not the Mean when it comes to the regulations of a sage.

32

Chapter 27, which consists of five short sections, has many parallels in the “Fangji” chapter of the

Liji. The fragments in this chapter read as a pastiche that is not overtly at odds with Dong Zhongshu’s views but that might not be confidently ascribed to him without stronger evidence. A partial exception is that both sections 27.1 and 27.3 deal with the equitable distribution of resources. This shared theme links the two sections, each roughly echoing positions taken by Dong in his third memorial to Emperor Wu.

As we noted earlier,

chapter 28 has two distinct halves. The ideal bureaucracy and system of government organization described in the first half derives its authority from the

Spring and Autumn and so is linked, at least in that sense, with the

Gongyang Erudite Dong Zhongshu. The scheme proposed in the second half, sections 28.8A through 28.8E, is an elaboration of ideas found in

Mencius 5B.2 and in the “Royal Regulations” chapter of the

Liji. Except for a general Confucian orientation, there is nothing particular in that half of the chapter to evoke the views of Dong. We assume that the unknown compiler of the

Chunqiu fanlu included in his edition the materials that make up both halves of

chapter 28 because he thought that they were in some way linked to Dong or one of his followers or that at least they could be taken (contradictions and all) to represent Dong Zhongshu’s views on government organization.