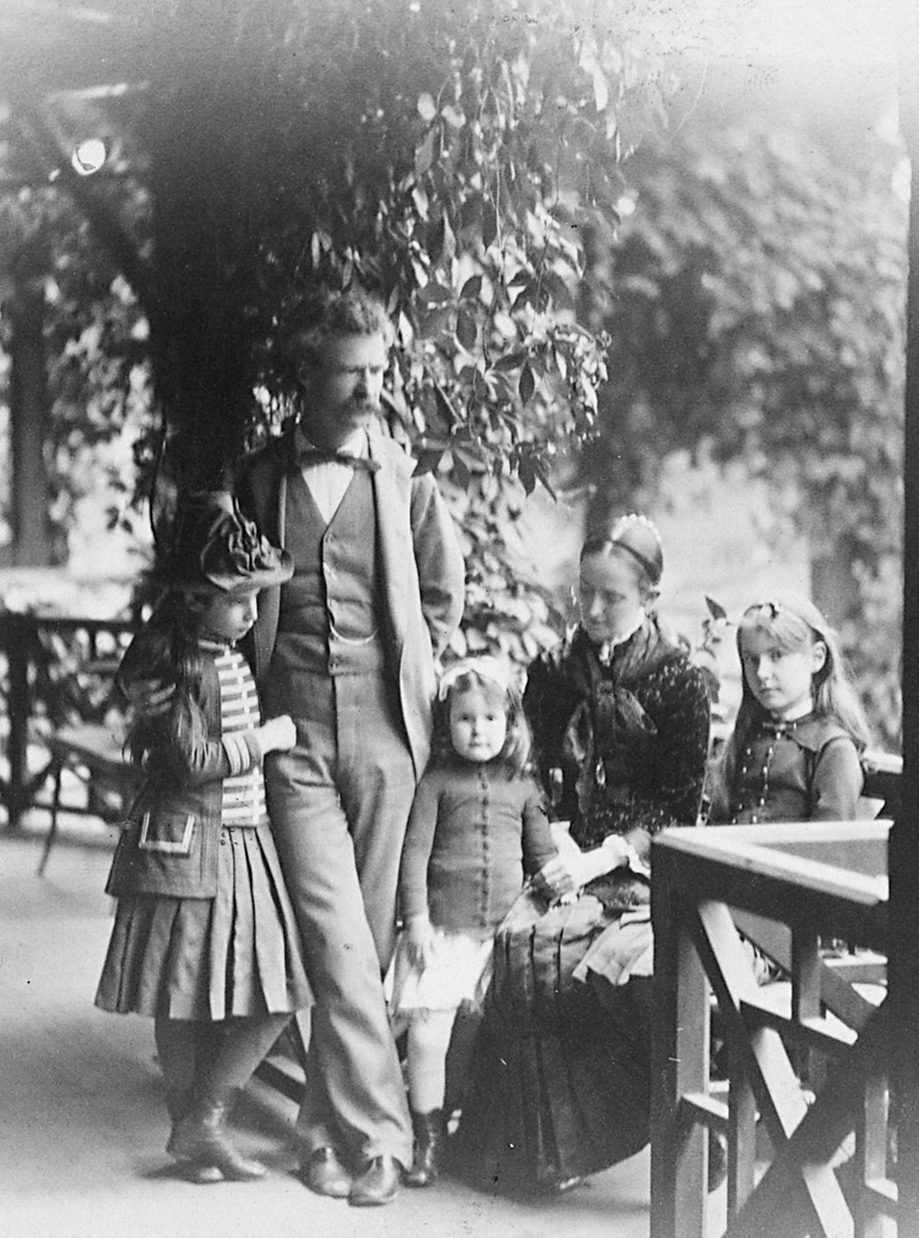

MARK TWAIN

A Family Sketch

Susy was born in Elmira, New York, in the house of her grandmother, Mrs. Olivia Langdon, on the 19th of March, 1872, and after tasting and testing life and its problems and mysteries under various conditions and in various lands, was buried from that house the 20th of August, 1896, in the twenty-fifth year of her age.

She was a magazine of feelings, and they were of all kinds and of all shades of force; and she was so volatile, as a little child, that sometimes the whole battery came into play in the short compass of a day. She was full of life, full of activity, full of fire, her waking hours were a crowding and hurrying procession of enthusiasms, with each one in its turn differing from the others in origin, subject and aspect. Joy, sorrow, anger, remorse, storm, sunshine, rain, darkness—they were all there: they came in a moment, and were gone as quickly. Her approval was passionate, her disapproval the same, and both were prompt. Her affections were strong, and toward some her love was of the nature of worship. Especially was this her attitude toward her mother. In all things she was intense: in her this characteristic was not a mere glow, dispensing warmth, but a consuming fire.

Her mother was able to govern her, but any others that attempted it failed. Her mother governed her through her affections, and by the aids of tact, truthfulness barren of trick or deception, a steady and steadying firmness, and an even-handed fairness and justice which compelled the child’s confidence. Susy learned in the beginning that there was one who would not say to her the thing which was not so, and whose promises, whether of reward or punishment, would be strictly kept; that there was one whom she must always obey, but whose commands would not come in a rude form or with show of temper.

As a result of this training, Susy’s obediences were almost always instant and willing, seldom reluctant and half-hearted. As a rule they were automatic, through habit, and cost no noticeable effort. In the nursery—even so early—Susy and her mother became friends, comrades, intimates, confidants, and remained so to the end.

While Susy’s nursery-training was safeguarding her from off ending other people’s dignity, it was also qualifying her to take care of her own. She was accustomed to courteous speech from her mother, but in a Record which we kept for a few years of the children’s small sayings and doings I find note—in my handwriting—of an exception to this rule:

One day Livy and Mrs. George Warner were talking earnestly in the library. Susy, who was playing about the floor, interrupted them several times; finally Livy said, rather sharply, “Susy, if you interrupt again, I will send you to the nursery.” A little later Livy saw Mrs. W. to the door; on the way back she saw Susy on the stairs, laboring her way up on all fours, a step at a time, and asked—

“Where are you going, Susy?”

“To the nursery, mamma.”

“What are you going up there for, dear—don’t you want to stay with me in the library?”

Susy was tempted—but only for a moment. Then she said with a gentle dignity which carried its own reproach—

“You didn’t speak to me right, mamma.”

She had been humiliated in the presence of one not by right entitled to witness it. Livy recognised that the charge was substantially just, and that a consideration of the matter was due—and possibly reparation. She carried Susy to the library and took her on her lap and reasoned the case with her, pointing out that there had been provocation. But Susy’s mind was clear, and her position definite: she conceded the provocation, she conceded the justice of the rebuke, she had no fault to find with those details; her whole case rested upon a single point—the manner of the reproof—a point from which she was not to be diverted by ingenuities of argument, but stuck patiently to it, listening reverently and regard fully, but returning to it in the pauses and saying gently, once or twice, “But you didn’t speak to me right, mamma.” Her position was not merely well selected and strong—by the laws of conduct governing the house it was impregnable; and she won her case, her mother finally giving the verdict in her favor and confessing that she had not “spoken to her right.”

Certain qualities of Susy’s mind are revealed in this little incident—qualities which were born to it and were permanent. It was not an accident that she perceived the several points involved in the case and was able to separate those which made for her mother from the point which made for herself, it was an exercise of a natural mental endowment which grew with her growth and remained an abiding possession.

Clara Langdon Clemens was born June 8th, 1874, and this circumstance set a new influence at work upon Susy’s development. Mother and father are but two—to be accurate, they are but one and a tenth—and they do their share as developers: but along a number of lines certain other developers do more work than they, their number being larger and their opportunities more abundant—i.e. brothers and sisters and servants. Susy was a blonde, Clara a brunette, and they were born with characters to match. As time wore along, the ideals of each modified the ideals and affected the character of the other; not in a large degree of course, but by shades.

Both children had good heads, but not equipped in the same way; Susy, when her spirit was at rest, was reflective, dreamy, spiritual, Clara was at all times alert, enterprising, business-like, earthy, orderly, practical. Some one said Susy was made of mind, Clara of matter—a generalization justified by appearances, at the time, but unjust to Clara, as the years by and by proved. In her early years Clara quite successfully concealed some of the most creditable elements of her make-up. Susy was sensitive, shrinking; and in danger timid; Clara was not shrinking, not timid, and she had a liking for risky ventures. Susy had an abundance of moral courage, and kept it up to standard by exercising it.

In going over the Record which we kept of the children’s remarks, it would seem that we set down Susy’s because they were wise, Clara’s because they were robustly practical, and Jean’s because they happened to be quaintly phrased.a

In Susy’s and Clara’s early days, nine months of the year were spent in the house which we built in Hartford, Connecticut. It was begun the year that Susy was born—1872—and finished and occupied in Clara’s birth year—1874.

In those long-past days we were diligent in the chase, and the library was the hunting-ground—“jungle,” by fiction of fancy—and there we hunted the tiger and the lion. I was the elephant, and bore Susy or Clara on my back—and sometimes both—and they carried the guns and shot the game. George, the colored ex-slave, was with us then; first and last he was in our service 18 years, and was as good as he was black—servant, in the matter of work, member of the family in the closer ties and larger enthusiasms of play. He was the lion—also the tiger; but preferably tiger, because as lion his roaring was over-robust, and embarrassed the hunt by scaring Susy. The elephant is left, and one of the hunters; but the other is at rest, and the tiger; and the hunting days are over.

The Clemenses’ Hartford house, 351 Farmington Avenue; today the Mark Twain House and Museum.

In the early days Patrick McAleer, the coachman, was with us—and had been with us from our wedding day, February 2, 1870. He was with us twenty-two years, marrying soon after he came to us, and rearing eight children while in our service, and educating them well.

Rosa, the German nurse, was a part of the household in the early years, and remained twelve.

Katy was a cotemporary of hers and George’s and Patrick’s; was with us in Europe twice, and is with us now. To the majority of our old personal friends these names will be familiar; they will remember their possessors ,and they will remember, also, that each was an interesting character, and not commonplace.

They would not be able to forget George, the colored man. I can speak of him at some length, without impropriety, he being no longer of this world nor caring for the things which concern it.

George was an accident. He came to wash some windows, and remained half a generation. He was a Maryland slave by birth; the Proclamation set him free, and as a young fellow he saw his fair share of the Civil War as body servant to General Devens. He was handsome, well built, shrewd, wise, polite, always good-natured, cheerful to gaiety, honest, religious, a cautious truth-speaker, devoted friend to the family, champion of its interests, a sort of idol to the children and a trial to Mrs. Clemens—not in all ways but in several. For he was as serenely and dispassionately slow about his work as he was thorough in parts of it; he was phenomenally forgetful; he would postpone work any time to join the children in their play if invited, and he was always being invited, for he was very strong, and always ready for service as horse, camel, elephant or any other kind of transportation required; he was fond of talking, and always willing to do it in the intervals of work—also willing to create the intervals; and finally, if a lie could be useful to Mrs. Clemens he would tell it. That was his worst fault, and of it he could not be cured. He placidly and courteously disposed of objections with the remark—

“Why, Mrs. Clemens, if I was to stop lying you couldn’t keep house a week.”

He was invaluable; for his large wisdoms and his good nature made up for his defects. He was the peace-maker in the kitchen—in fact the peace keeper, for by his good sense and right spirit and mollifying tongue he adjusted disputes in that quarter before they reached the quarrel-point. The materials for war were all there. There was a time when we had a colored cook—Presbyterian; George—Methodist; Rosa, German nurse— Lutheran; Katy, American-Irish—Roman Catholic; Kosloffska, Pole, wet-nurse—Greek Catholic; “English Mary,” some kind of a non-conformist; yet under George’s benignant influence and capable diplomacy it was a Barnum’s Happy Family, and remained so.

There was nothing commonplace about George. He had a remarkably good head; his promise was good, his note was good; he could be trusted to any extent with money or other valuables; his word was worth par, when he was not protecting Mrs. Clemens or the family interests or furnishing information about a horse to a person he was purposing to get a bet out of; he was strenuously religious, he was deacon and autocrat of the African Methodist Church; no dirt, no profanity, ever soiled his speech, and he neither drank nor smoked; he was thrifty, he had an acute financial eye, he acquired a house and a wife not very long after he came with us, and at any time after his first five years’ service with us his check was good for $10,000. He ruled his race in the town, he was its trusted political leader, and (barring election-eve accidents) he could tell the Republican Committee how its vote would go, to a man, before the polls opened on election day. His people sought his advice in their troubles, and he kept many a case of theirs out of court by settling it himself. He was well and creditably known to the best whites in the town, and he had the respect and I may say the warm friendly regard of every visiting intimate of our house. Added to all this, he could put a lighted candle in his mouth and close his lips upon it. Consider the influence of a glory like that upon our little kids in the nursery. To them he was something more than mortal; and to their affection for him they added an awed and reverent admiration.

Moreover, he had a mysterious influence over animals—so the children believed. He conferred a human intelligence upon Abner the tomcat—so he made them believe. He told them he had instructed Abner that four pressures of the button was his ring, and he said Abner would obey that call. The children marveled, and wanted it tried. George went to the kitchen to set the door open, so that Abner could enter the dining room; then we rang for him, and sure enough he appeared. The children were lost in astonishment at Abner’s promptness and willingness, for they had not noticed that there was something about the humping plunge of his entrance that was suggestive of assistance from behind. Then they wondered how he could tell his ring from the other rings—could he count? Probably. We could try experiments and draw conclusions. Abner was removed. Two pressures brought no Abner, it brought Rosa; three brought some one else; five got no response, there being no such ring in the list; then, under great excitement No. 4 was tried once more, and once more Abner plunged in with his suspicious humping impulse. That settled it: Abner could count, and George was the magician that had expanded his intelligence.

“How did you do it, George!”

That was the question; but George reserved the secret of his occult powers. His reputation was enlarged; Abner’s, too, and Abner’s needed it; if any one had gone around, before that, selecting bright cats by evidence of personal aspect, Abner would not have been elected. He was grave, but it was the gravity of dulness, of mental vacancy, his face was quite expressionless, and even had an arid look.

It will not be imagined that George became a moneyed man on his wages of thirty dollars a month. No, his money came from betting. His first speculations in that field were upon horses. It was not chance-work; he did not lay a bet until he knew all that a smart and diligent person could learn about the horses that were to run and the jockeys that were to ride them; then he laid his bets fearlessly. Every day, in the Hartford racing-season, he made large winnings; and while he waited at breakfast next morning he allowed the fact and the amount to escape him casually. Mainly for Susy’s benefit, who had been made to believe that betting was immoral, and she was always trying to wean George from it, and was constantly being beguiled, by his arts, into thinking his reform was imminent, and likely to happen at any moment. Then he would fall—and report a “pile” at break fast; reform again, and fall again before night; and so on, enjoying her irritations and reproaches, and her solemn warnings that disaster would overtake him yet. If he made a particularly rich haul, we knew it by the ostentatious profundity of his sadnesses and depressions as he served at break fast next morning,—a trap set for Susy. She would notice his sadness, presently, and say, eagerly and hopefully, “It has happened, George, I told you it would, and you are served just right—how much did you lose?—I hope ever so much; nothing else can teach you.” George’s sigh would be ready, and also his confession, along with a properly repentant look—

“Yes, Miss Susy, I had hard luck—something was wrong, I can’t make out what it was, but I hope and believe it will learn me. I only won eight hundred dollars.”

George reported all his victories to us, but if he ever suffered a loss on a horse-race we never found it out; if he had a secret of the kind it was not allowed to escape him, by either his tongue or his countenance.

By and by he added elections to his sources of income. Again he was methodical, systematic, pains-taking, thorough. Before he risked a dollar on a candidate or against him, he knew all about the man and his chances. He searched diligently, he allowed no source of information to escape a levy. For many years several chief citizens arrived at our house every Friday evening in the home-season, to play billiards—Governor Robinson, Mr. Edward M. Bunce, Mr. Charles E. Perkins, Mr. Sam. Dunham, and Mr. Whitmore. As a rule, one or two of the team brought their wives, who spent the evening with Mrs. Clemens in the library. These ladies were sure to arrive in that room without their husbands: because they and the rest of the gentlemen were in George’s clutches in the front hall, getting milked of political information. Mrs. Clemens was never able to break up this scandalous business, for the men liked George, they admired him, too, so they abetted him in his misconduct and were quite willing to help him the best they could.

He was as successful with his election bets as he was with his turf ventures. In both cases his idea was that a bet was not won until it was won; therefore it required watching, down to the last moment. This principle saved him from financial shipwreck, on at least one occasion. He had placed a deal of money on Mr. Blaine, and considered it perfectly safe, provided nothing happened. But things could happen, and he kept a watchful eye out, all the time. By and by came that thunderclap out of the blue, “Rum, Romanism, and Rebellion,” and Mr. Blaine fell, fatally smitten by the friendly tongue of a clerical idiot. From one of his subsidized information sources George learned of it three hours before it had gotten currency in Hartford, and he allowed no grass to grow under his feet. Within that time he had covered his Blaine bets out of sight with bets at one to two against him. He came out of that close place a heavy winner.

He was an earnest Republican, but that was a matter to itself; he did not allow politics to intrude itself into his business.

George found that in order to be able to bet intelligently upon State and National elections it was necessary to be exhaustively posted in a wide array of details competent to affect results. Experience presently wrung from him this tardy justice toward me—

“Mrs. Clemens, when I used to see Mr. Clemens setting around with a pen and talking about his ‘work,’ I never said anything, it warn’t my place, but I had my opinions about that kind of language, jist the same. But since I’ve took up with the election business I reconnize ’t I was ignorant and foolish. I’ve found out, now, that when a man uses these” (holding out his big hands), “it’s—well, it’s any po’ thing you’ve a mind to call it; but when he uses these” (tapping his forehead), “it’s work, sho’s you bawn, and even that ain’t hardly any name for it!”

As an instance of what George could do on the turf, I offer this. Once in the summer vacation I arrived without notice in Hartford, entered the house by the front door without help of a latch-key, and found the place silent and the servants absent. Toward sunset George came in the back way, and I was a surprise for him. I reproached him for leaving the house unprotected, and said that at least one sentinel should have been left on duty. He was not troubled, not crushed. He said the burglar alarm would scare any one away who tried to get in. I said—

“It wasn’t on. Moreover, any one could enter that wanted to, for the front door was not even on the latch. I just turned the knob and came in.”

He paled to the tint of new leather, and reeled in his tracks. Then, without a word he flew up the stairs three steps at a jump, and presently came panting down, with a fat bundle in his hand. It was money—greenbacks.

“Goodness, what a start you did give me, Mr. Clemens!” he said. “I had fifteen hundred dollars betwixt my mattresses. But she’s all right.”

He had been away six days at Rochester, and had won it at the races.

In Hartford he did a thriving banking business in a private way among his people—for a healthy commission. And he lost nothing, for he did not lend on doubtful securities.

I was back, for a moment, in 1893, when we had been away two years in Europe; George called at the hotel, faultlessly dressed, as was his wont, and we walked up town together, talking about “the Madam” and the children, and incidentally about his own affairs. He had been serving as a waiter a couple of years, at the Union League Club, and acting as banker for the other waiters, forty in number, of his own race. He lent money to them by the month, at rather high interest, and as security he took their written orders on the cashier for their maturing wages, the orders including interest and principal.

Also, he was lending to white men outside; and on no kinds of security but two—gold watches and diamonds. He had about a hatful of these trifles in the Club safe. The times were desperate, failure and ruin were everywhere, woe sat upon every countenance, I had seen nothing like it before, I have seen nothing like it since. But George’s ark floated serene upon the troubled waters, his white teeth shone through his pleasant smile in the old way, he was a prosperous and happy person, and about the only one thus conditioned I met in New York.

To save ciphering, he was keeping deposits in three banks. He kept his capital in one, his interest-accumulations in another, and in the third he daily placed every copper, every nickel and every piece of silver received by him between getting up and going to bed, from whatever source it might come, whether as tips, or in making change, or even as capital resulting from the paying back of small loans. This third deposit was a sacred thing, the sacredest George had. It was for the education of his sole child, a little daughter nine months old.

It had been accumulating since the child’s birth. George said—

“It’ll be a humping lot by and by, Mr. Clemens, when she begins to need it. I’ve had to pull along the best I could without any learning but what little I could pick up as I had a chance; but I know the power an education is, and when I used to see little Miss Susy and Miss Clara and Miss Jean pegging away in the schoolroom, and Miss Foote learning them everything in the world, I made up my mind that if ever I had a little daughter I’d educate her up to the eye-lids if I starved for it!”

As I have suggested before, mamma and papa and the governess do their share—such as it is—in moulding a child, and the servants and other unconsidered circumstances do their share; and a potent share it is. George had unwittingly helped to train our little people, and now it appeared that in the meantime they had been as unwittingly helping to train him. We—one and all—are merely what our training makes us; and in it all our world takes a hand.

I am reminded that I, also, contributed a trifle once to George’s training in the early days there at home in Hartford. One morning he appeared in my study in a high state of excitement, and wanted to borrow my revolver. He had had a rupture with a colored man, and was going to kill him on sight. I was surprised; for George was the best-natured man in the world, and the humanest; and now here was this bad streak in him and I had never suspected it. Presently, as he talked along, I got new light. The bad streak was bogus. I saw that at bottom he didn’t want to kill any one—he only wanted some person of known wisdom and high authority to persuade him out of it; it would save his character with his people; they would see that he was properly bloodthirsty, but had been obliged to yield to wise and righteous counsel. So I reserved my counsel; I put new cartridges in the revolver, and handed it to him, saying—

“Keep cool, and don’t fire from a distance. Close in on him and make sure work. Hit him in the breast.”

He was visibly surprised—and disappointed. He began lamely to hedge, and I to misunderstand. Before long he was hunting for excuses to spare the man, and I was zealously urging him to kill him. In the end he was giving me an earnest sermon upon my depraved morals, and trying to lift me to a higher spiritual level. Finally he said—

“Would you kill him, Mr. Clemens? If you was in my place would you, really?”

“Certainly. Nothing is so sweet as revenge. Now here is an insulter who has no wife and no children—”

“Oh, no, Mr. Clemens, he’s got a wife and four little children.”

I was outraged, then—apparently—and turned upon him and said, indignantly—

“You-u-u—scoundrel! You knew that all the time? Do you mean to tell me that you actually had it in your hard nature to break the hearts and reduce to poverty and misery and despair those innocent creatures for something somebody else had done?”

It was George’s turn to be staggered, and he was. He said, remorsefully—

“Mr. Clemens, as I’m a standing here I never seen it in that light before! I was a going to take it out of the wrong ones, that hadn’t ever done me any harm—I never thought of that before! Now, sir, they can jist call me what they want to—I’ll stand it.”

On our way up town that day in New York I turned in at the Century building, and made George go up with me. The array of clerks in the great counting-room glanced up with curiosity—a white man and a negro walking together was a new spectacle to them. The glance embarrassed George, but not me, for the companionship was proper: in some ways he was my equal, in some others my superior; and besides, deep down in my interior I knew that the difference between any two of those poor transient things called human beings that have ever crawled about this world and then hid their little vanities in the compassionate shelter of the grave was but microscopic, trivial, a mere difference between worms. In the first editorial room I introduced “Mr. Griffin” to Mr. Buel and Mr. Johnson, and embarrassed all three. Conversation was difficult. I went into the main editorial room and found Mr. Gilder there. He said—

“You are just the man!” He handed me a type-written manuscript. “Read that first paragraph and tell me what you think of it.”

I looked around; George was decamping. I called him back, introduced him to Mr. Gilder, and said—

“Listen to this, George.” I read the paragraph and asked him how its literary quality struck him. He very modestly gave his opinion in a couple of sentences, and I returned the manuscript to Gilder with the remark that that was my opinion also. Conversation was difficult again—which was satisfactory to me, for I was there to make an impression. This accomplished, I left, and on my way was gratified to notice that many employes put in a casual appearance here and there and yonder and took a sight of George and me.

Passing the St. Nicholas editorial room Mr. Clarke hailed me and said—

“Come in, Mark, I’ve got something to show you.”

I made George come in, too. The thing to be shown was a design for a new cover for St. Nicholas. Mr. Clarke said—

“What do you think of it?”

I examined it a while, then handed it without comment to George, introduced him, and asked for his opinion. With diffidence, but honestly, he gave it; I endorsed it, and returned the design to Clarke. Conversation not fluent. Mr. Carey of the general business department appeared, and proposed refreshments. Down in Union Square George dropped behind, but I brought him forward, introduced him to Carey, and placed him between us. There had been a prize fight the night before, between a white man and a negro. Presently I said—

“George, what did you get out of that fight last night?”

“Six hundred dollars, sir.”

Carey glanced across me at him with interest, and said—

“Did you bet on the winner?”

“Yes, sir.”

“He was the white man. Was it quite patriotic to bet against your own color?”

“Betting is business, sir, patriotism is sentiment. They don’t belong together. In politics I’m colored; in a bet I put up on the best man, I ain’t particular about his paint. That white man had a record; so had the coon, but ’twas watered.”

Carey was evidently impressed. When we arrived at Carey’s refreshment place George politely excused himself and went his way. Presently Carey said—

“What’s the game? That’s no commonplace coon. Who is that?”

I said it was a long story—“wait till we get back to the Century.”

There the editorial people listened to the history of George Griffin, and were sorry they hadn’t been acquainted with it before he came—they would have “shaken hands, and been glad to; wouldn’t I bring him again?”

We sailed for Europe in 1891. Shortly afterward George, concluding that we were not coming back soon—knowing it, in fact—applied for a place at the Union League Club. He was a stranger. He was asked—

“Recommendation?”

He had a gilt-edged one in his pocket from us, but he kept it there, and answered simply—

“Sixteen years in the one family—in Hartford.”

“Sixteen years. Then you ought to be able to prove that. By the family, or some known person. Isn’t there someone who can speak for you?”

“Yes, sir—anybody in Hartford.”

“Meaning everybody?”

“Yes, sir—from Senator Hawley down.”

That was George’s style. He had a reputation, and he wanted the fact known. There were plenty of Hartford members of the Union League Club, and he knew what they would say. He served there until his death in 1897, faithfully corresponding with the family all the while, and returning with interest the children’s affection for him. Susy passed to her rest the year before George died. He was performing his duties in the Club until toward midnight of the 7th May, then complained of a pain at his heart and went to bed. He was found dead in his bed in the morning.

We were living in London at the time. I early learned what had happened, but I kept it from the family as long as I could, the midnight of Susy’s loss being still upon them and they being ill fitted to bear an added sorrow; but as the months wore on and no letter came from George in answer to theirs, they became uneasy, and were about to write him and ask what the matter was; then I spoke.

As I have already indicated, Mrs. Clemens and I, and Miss Foote the governess, were in our respective degrees of efficiency and opportunity trainers of the children—conscious and intentional ones—and we were reinforced in our work by the usual and formidable multitude of unconscious and unintentional trainers, such as servants, friends, visitors, books, dogs, cats, horses, cows, accidents, travel, joys, sorrows, lies, slanders, oppositions, persuasions, good and evil beguilements, treacheries, fidelities, the tireless and everlasting impact of character-forming exterior influences which begin their strenuous assault at the cradle and only end it at the grave. Books, home, the school and the pulpit may and must do the directing—it is their limited but lofty and powerful office—but the countless outside unconscious and unintentional trainers do the real work, and over them the responsible superintendents have no considerable supervision or authority.

Conscious teaching is good and necessary, and in a hundred instances it effects its purpose, while in a hundred others it fails and the purpose, if accomplished at all, is accomplished by some other agent or influence. I suppose that in most cases changes take place in us without our being aware of it at the time, and in after life we give the credit of it—if it be of a creditable nature—to mamma, or the school or the pulpit. But I know of one case where a change was wrought in me by an outside influence—where teaching had failed,—and I was profoundly aware of the change when it happened. And so I know that the fact that for more than fifty-five years I have not wantonly injured a dumb creature is not to be credited to home, school or pulpit, but to a momentary outside influence. When I was a boy my mother pleaded for the fishes and the birds and tried to persuade me to spare them, but I went on taking their lives unmoved, until at last I shot a bird that sat in a high tree, with its head tilted back, and pouring out a grateful song from an innocent heart. It toppled from its perch and came floating down limp and forlorn and fell at my feet, its song quenched and its unoffending life extinguished. I had not needed that harmless creature, I had destroyed it wantonly, and I felt all that an assassin feels, of grief and remorse when his deed comes home to him and he wishes he could undo it and have his hands and his soul clean again from accusing blood. One department of my education, theretofore long and diligently and fruitlessly labored upon, was closed by that single application of an outside and unsalaried influence, and could take down its sign and put away its books and its admonitions permanently.

In my turn I admonished the children not to hurt animals; also to protect weak animals from stronger ones. This teaching succeeded—and not only in the spirit but in the letter. When Clara was small—small enough to wear a shoe the size of a cowslip—she suddenly brought this shoe down with determined energy, one day, dragged it rearward with an emphatic rake, then stooped down to examine results. We inquired, and she explained—

“The naughty big ant was trying to kill the little one!”

Neither of them survived the generous interference.

Among the household’s board of auxiliary and unconscious trainers, four of the servants were especially influential—Patrick, George, Katy, and Rosa the German nurse; strong and definite characters, all, and all equipped with uncommonly good heads and hearts. Temporarily there was another influence—Clara’s wet nurses. No. 1 was a mulatto, No. 2 was half American half Irish, No. 3 was half German half Dutch, No. 4 was Irish, No. 5 was apparently Irish, with a powerful strain of Egyptian in her. This one ended the procession—and in great style, too. For some little time Clara was rich in given-names drawn from the surnames of these nurses, and was taught to string them together as well as her incompetent tongue would let her, as a show-off for the admiration of visitors, when required to “be nice and tell the ladies your name.” As she did it with proper gravity and earnestness, not knowing there was any joke in it, it went very well: “Clara Lewis O’Day Botheker McAleer McLaughlin Clemens.”

It has always been held that mother’s milk imparts to the child certain details of the mother’s make-up in permanency—such as character, disposition, tastes, inclinations, traces of nationality and so on. Supposably, then, Clara is a hybrid and a polyglot, a person of no particular country or breed, a General Member of the Human Race, a Cosmopolitan.

She got valuable details of construction out of those other contributors, no doubt; no doubt they laid the foundations of what she is now, but it was the mighty Egyptian that did the final work and reared upon it the imposing super structure. There was never any wet-nurse like that one—the unique, the sublime, the unapproachable! She stood six feet in her stockings, she was perfect in form and contour, raven-haired, dark as an Indian, stately, carrying her head like an empress, she had the martial port and stride of a grenadier, and the pluck and strength of a battalion of them. In professional capacity the cow was a poor thing compared to her, and not even the pump was qualified to take on airs where she was. She was as independent as the flag, she was indifferent to morals and principles, she disdained company, and marched in a procession by herself. She was as healthy as iron, she had the appetite of a crocodile, the stomach of a cellar, and the digestion of a quartz-mill. Scorning the adamantine law that a wet-nurse must par take of delicate things only, she devoured anything and everything she could get her hands on, shoveling into her person fiendish combinations of fresh pork, lemon pie, boiled cabbage, ice cream, green apples, pickled tripe, raw turnips, and washing the cargo down with freshets of coffee, tea, brandy, whisky, turpentine, kerosene—anything that was liquid; she smoked pipes, cigars, cigarettes, she whooped like a Pawnee and swore like a demon; and then she would go up stairs loaded as described and perfectly delight the baby with a banquet which ought to have killed it at thirty yards, but which only made it happy and fat and contented and boozy. No child but this one ever had such grand and wholesome service. The giantess raided my tobacco and cigar department every day; no drinkable thing was safe from her if you turned your back a moment; and in addition to the great quantities of strong liquors which she bought down town every day and consumed, she drank 256 pint bottles of beer in our house in one month, and that month the shortest one of the year. These things sound impossible, but they are facts. She was a wonder, a portent, that Egyptian.

Patrick the coachman was a part of our wedding outfit, therefore he had been with us two years already when Susy was born. He was Irish; young, slender, bright, quick as a cat, a master of his craft, and one of the only three persons I have had long acquaintance with who could be trusted to do their work well and faithfully without supervision. He was one of the three, I am not the other two—nor either of them. They are John the gardener and his wife—Irish; they were in our service about twenty years.

Patrick, from the earliest days, thirty-six years ago, when he was perhaps twenty-five, carried on his work systematically, competently, and without orders. He kept his horses and carriages and cows in good condition; he kept the bins and the hayloft full; if a horse or a cow was unsatisfactory he made a change; he filled the cellars with coal and wood in the summer while we were away; as soon as a snow-storm was ended he was out with his snow-plow; if a thing needed mending he attended to it at once. He had long foresight, and a memory which was so good that he never seemed to forget anything. In the house, supplies were constantly failing at critical moments, and George’s explanation never varied its form, “I declare, I forgotten it”—which was monstrous. This phrase was not in Patrick’s book, nor John’s.

Patrick rode horseback with the children in the forenoons; in the afternoons he drove them out, with their mother; Susy never on the box, Clara always there, holding the reins in the safe places and prattling a stream; and when she outgrew the situation Jean took it, and continued the din of talk—inquiries, of course; it is what a child deals in. The children had a deep admiration for Patrick, for he was a spanking driver, yet never had an accident; and besides, to them he seemed to know everything and how to do everything. They conferred their society upon him freely in the stable, and he protected them while they took risks in petting the horses in the stalls and in riding the reluctant calves. Also he allowed them, mornings, to help him drive the ducks down to the stream which lazily flowed through the grounds, and back to the stable at sunset. Furthermore, he allowed them to look on and shrink and shiver and compassionately exclaim, when he had a case of surgery on hand—which was rather frequent when the ducks were youthful. They would go to sleep on the water, and the mud-turtles would get them by the feet and chew until Patrick happened along and released them. Then he brought them up the slope and sat in the shade of the long quarter-deck called “the ombra” and bandaged the stumps of the feet with rags while the children helped the ducks do the suffering. He slaughtered a mess of the birds for the table pretty frequently, and this conduct got him protests and rebukes. Once Jean said—

“I wonder God lets us have so much ducks, Patrick kills them so.”

A proper attitude for one who was by and by, in her sixteenth year, to be the founder of a branch of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

Patrick was apt to be around when needed, and this happened once when he was sorely needed indeed. On the second floor of the stable there was a large oat-bin, whose lid shut with a spring. It had a couple of feet of oats in it. Susy, Clara, and Daisy Warner climbed into it, the lid fell and they were prisoners, there in the dark. They were not able to help themselves, their case was serious, they would soon exhaust the air in that box, then they would suffocate. Our house was not close by; Patrick’s house was a part of the stable, but between it and the stable were thick walls, muffled screams could not bore through them. We at home in the house were comfortable and serene, not suspecting that an awful tragedy was imminent on the premises. Patrick arrived from down town and happened to step into the carriage house instead of passing along to his own door, as had been his purpose. He noticed dull cries, but could not at once tell whence they proceeded—sounds are difficult things to locate. A stupider man would have gone outside, and lost his head, and hunted frantically everywhere but in the right place; a few minutes of this would have answered all tragic purposes. But Patrick was not stupid; he kept his head and listened, then moved when he had reached a conclusion.

It was not Susy that arranged that scrape, it was Clara; Susy was not an inventor of adventures, she was only an accommodating and persuadable follower of reckless inventors of such things, for in her gentle make-up were no nineteen second-hand nationalities and the evil energies of that Egyptian volcano. Susy took, in its turn, each step of the series that led up to the scrape, but she originated none of them, it was mainly Clara’s work, the outcome of her heredities. She was within a day or two of eight years old at the time. Miss Foote required of the children a weekly composition, and Clara utilized the episode in satisfaction of that law. It exhibits Clara’s literary gait of that day, and I will copy it here from the original document:

The barn by Clara Clemens.

Caught in the Oat Bin, Daisy, Susie and I went up in the barn to play in the hay, there was a great big Oat box up there and I said “Let’s get on it” and Daisy said “Yes,” so Susie and Daisy pushed me up, Then Susie tried to get up but she could not, I saw a big oil box, and I said “O, Susie take the oil box over there and put it on the steps and you can get on that,” and so she did, and they all got up; I began jumping off from it they all were afraid, I was too, at first, And then Daisy said “Let’s get in” so I jumped in and then Daisy did; Susie was afraid to get in because she thought there was no bottom to it, but we dug and dug and showed that there was a bottom. So pretty soon she jumped in; then we began to play and pretty soon the cover came down. Then it was roasting hot, in there. Daisy and Susie pushed and I screamed, Patrick thought he heard some one screaming, but he thought we were only playing, still as I kept screaming he thought he would come up and see what was the matter, He found the noise came from the oat box and he opened the lid and let us out, We could not see at all and we felt very hot in there, Patrick said we could have smothered in a little while.

The End.

It is pitiful, those frightened little prisoners struggling, pushing and screaming in the swelter and smother of that pitch-dark hole; I often see that picture and feel the pathos of it. And particularly I feel Susy’s fright; that of the others had limits, perhaps, but in such circumstances hers would have none. She was by nature timid; also, she had a forceful imagination. In time of peril this is a powerful combination. The dark closet was never put in Susy’s list of punishments; it would have been much too effective. It was tried with Clara, when she was four or five years old, but without adequate results. She was always able to entertain herself, and easily did it in this instance; she did not mind the darkness, and she was the only one that was sorry when the prison-term was up. The Egyptian was probably many times in places similar to that—by request of the State. Susy required much punishing while she was little, but not after she was six or seven years old. By that time she was become a wise and thoughtful small philosopher and able to shut the exits upon her fierce exuberances of temper and keep herself under control. But even Susy’s timidity had limits. She was not discomposed by runaways and cab-collisions, and she enjoyed storms and was not afraid of lightning; in a town of the Haute Savoie the night after the assassination of President Car not, when a mob assailed the hotel with stones and threatened to destroy it unless the Italian servants were delivered into its hands to be lynched, she kept her head. On the other hand sea-voyaging was a torture to her, and a large part of the torture was bred of a constant fear at night that the ship would burn.

Rosa, the German nurse, who was with us ten or twelve years, was a pleasant influence in the nursery and in the house. She had a smart sense of humor, an easy and cordial laugh which was catching, and a cheery spirit which pervaded the premises like an atmosphere. She had good sense, good courage, unusual presence of mind in seasons of danger, and a sound judgment in exercising it. In a hotel in Baden Baden once, when Clara was two years old, and sly and enterprising, and a difficult person to keep track of, an elderly German chambermaid burst into our quarters, pale and frightened, and tried to say something, but couldn’t. Rosa did not wait for the woman to find her tongue, but moved promptly out to see for herself what the trouble might be. We were on the third floor. Clara had squeezed her body through the balusters, and was making the trip along them, inch by inch, her body overhanging the vacancy which extended thence to the marble floor three stories below. Rosa did not fly to the child and scare it and bring on a tragedy, but stood at a distance and said in an ordinary voice,

“I have something pretty for thee, Kindchen—wait till I bring it.”

Then she walked forward and lifted Clara over the balusters without rousing any opposition, and the danger was over for that time. Four years later, at a seaside resort, Clara was drowning, in the midst of a crowd of women and children, who stood paralyzed and helpless and did nothing; Rosa had to run a matter of twenty yards, but she covered the distance in time and saved what was left of the child—a doubtful asset, to all appearances, but, as it turned out, less doubtful than the appearances promised.

Also, Rosa had a two-thirds share in “the Three Days;” the barber had the other third. We were living in the Hartford home at the time, and it was cold weather. Clara had diphtheria, and her crib was in our bedroom, which was on the second floor; over the crib was built a tent of blankets, into which projected the pipe of a steaming apparatus which stood upon the floor. Mrs. Clemens left the room for a little while, and presently Rosa entered on an errand, and found a conflagration; the alcohol lamp had set fire to the tent and the blankets were blazing. Rosa snatched the patient out and put her on the bed, then gathered up the burning mattrass and blankets and threw them out of the window. The crib itself had caught fire; she smothered that detail. Clara’s burns were very slight, and Rosa got no burns, except on her hands.

That was the First Day. The next morning Jean, the baby, was asleep in her crib in front of a vigorous wood fire in the nursery on the second floor. The crib had a tall lawn canopy over it. A spark was driven through the close-webbed fire-screen and it lit on the slant of the canopy, and presently the result was a blaze. After a little a Polish servant-woman entered the nursery, caught sight of the tall flame, and rushed out shrieking. That brought Rosa from somewhere, and she rescued the child and threw the burning mattrass and bedding out of the window. The baby was slightly burnt in several spots, and again Rosa’s hands suffered, but otherwise no harm was done. Nothing but instant perception of the right thing to do, and lightning promptness in doing it could save the children’s lives, a minute’s delay in either case would have been fatal; but Rosa had the quick eye, the sane mind and the prompt hand, and these great qualities made her mistress of the emergency.

The next day was the Third Day, and completed the series. The barber came out daily from town to shave me. His function was performed in a room on the first floor—it was the rule; but this time, by luck, he was sent up to the schoolroom, which adjoined the nursery, on the second floor. He knocked; there being no response, he entered. Susy’s back was visible at the far end of the room; she was deep in a piano lesson, and unconscious of other matters. A log had burned in two, the ends had fallen against the heavy woodwork which enclosed the fireplace and supported the mantel piece, and the conflagration was just beginning. Five minutes later the house would have been past saving. The barber did the requisite thing, and the danger was over. So ended what in the family history we call “the Three Days,” and aggrandize them with capital letters, as is proper.

Rosa was a good disciplinarian, and faithful to her orders. She was not allowed to talk to the children in any tongue but German. Susy was amenable to law and reason, but when Clara was a little chap she several times flew out against this arrangement, and once in Hesse Cassel, with grieved and resentful tears in her eyes, she said to Miss Spaulding,—

“Aunt Clara, I wish God hadn’t made Rosa in German.”

Rosa was with us until 1883, when she married a young farmer in the State of New York, and went to live with him on his farm. When the young corn began to sprout the crows took to pulling it up, and then an incident followed whose humor Rosa was quite competent to appreciate. She had spread out and stuck up an old umbrella to do service as a scarecrow, and was sitting on the porch waiting to see what the marauders would think of it. She had not long to wait; soon rain began to fall, and the crows pulled up corn and carried it in under the umbrella and ate it—with thanks to the provider of the shelter!

Katy was a potent influence, all over the premises. Fidelity, truthfulness, courage, magnanimity, personal dignity, a pole-star for steadiness—these were her equipment, along with a heart of Irish warmth, quick Irish wit, and a good store of that veiled and shimmering and half-surreptitious humor which is the best feature of the “American” brand—or of any brand, for that matter. The drift of the years has not spirited away any of these qualities; they are her possession still.

Of course there were birds of passage—servants who tarried a while, were dissatisfied with us or we with them, and presently vanished out of our life, making but slight impression upon it for good or bad, perhaps, and leaving it substantially unmodified by their contributions in the way of training. The Egyptian always excepted. And possibly Elise,—a temporary nurse-help for Jean. Elise was a pretty and plump and fresh young maiden of fifteen, right out of a village in the heart of Germany, speaking no language but her own, innocent as a bird, joyous as fifty birds, and as noisy as a million of them. She was sincerely and germanically religious, and it is possible that she did teach us some little something or other—to swear, perhaps. For she had that German gift; and had it in the German way, which does not offend, and is not meant to offend. Her speeches were well larded with harmless handlings of the sacred names. “Allmächtiger Gott!” “Gott im Himmel!” “Heilige Mutter Gottes!” “Nun, schönen Dank, dass ist fertig, bei Gott!” “Lieber wäre ich in der Hölle verloren als dass ich dasselbe wieder thun müssen!” “O, Herr Jesus, ja! ich komme gleich!” Apostrophe to the soup, which had burnt her mouth: “Oooh! die gottverdammte Suppe!”b

Jean, the baby, catching the sound of distant thunder rumbling and crashing down the sky one day, listened a moment to make sure, then nodded her head as one whose doubts are removed, and said musingly—

“That’s Elise, again.”

One is obliged to like the German profanity, after the ear has grown used to it, because it is so guileless and picturesque and alluring. As winning a swearer as we have known was a Baroness in Munich of blameless life, sweet and lovely in her nature, and deeply religious. During the four months we spent there in the winter of 1878–9, our traveling comrade, Miss Clara Spaulding, spent a good deal of time in her house, and the two became intimate friends. The Baroness was fond of believing that in many pleasant ways the Germans and the Americans were alike, and once she hit upon this happy resemblance:

“Why, if you notice, we even talk alike. We say Ach Gott, and you say goddam!”

The Hartford house stood upon the frontier where town and country met, the one side of the premises being in the town and the other side within the cover of the original forest. The nearest neighbor, in one direction—across the sward with no fence between—was Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe; and the nearest neighbors in another direction—through the chestnuts, with no fences—were the Warners (Charles Dudley and George). Further away were other intimates: John Hooker and Isabella Beecher Hooker, the Norman Smiths, the Perkinses, the Jewells and Whitmores, Rev. Francis Goodwin; Rev. Joseph Twichell (shepherd of our flock and uncle by adoption to the children); Rev. Dr. Burton, Rev. Dr. Parker, Gen. Hawley, Hammond Trumbull, the Robinsons, the Tafts, President Smith of Trinity, the Dunhams, the Hamersleys, the Colts, the Gays, the Cheneys, General Franklin, the Hillyers, the Bunces and so on; and in the very earliest days one had the momentary privilege of a word with the Rev. Horace Bushnell, whose body was failing and his step halting, but his great intellect had suffered no impairment, and in his wonderful eyes the deeps had not shoaled. Now and then the Howellses and the Aldriches and James T. Fields came down from Boston, and Stedman and Bayard Taylor up from New York, and Nasby from Toledo, and Stanley from Africa, and Charles Kingsley and Henry Irving from England, and Stepniak from Russia, and other bright lights from otherwheres. In their several ways, all trainers of the family, and rarely competent! When Susy was twelve years old General Grant described one or two of Sheridan’s achievements to her, and gave his reasons for regarding Sheridan as the first general of the age; and later, when she was fifteen or sixteen, Kipling called (at the summer-home near Elmira), and spoke with her and left his card in her hand; and she kept it, and was able to produce it by and by, when Kipling’s name shot up out of the unknown and filled the world with its fame.

From all these friends and acquaintances the children unconsciously gathered something, little or much, and it went to the sum of their training, for all impressions leave effects, none go wholly to waste.

“The Farm.”

Our summers were spent at “The Farm”—full name, “Quarry Farm”—the home of Theodore and Susan Crane, brother-in-law and sister of Mrs. Clemens. There the children’s training was continued by Katy and Rosa, strongly reinforced by John T. Lewis, colored, ex-slave (Mr. Crane’s farmer), Aunty Cord, colored, ex-slave (cook), David, colored, coachman, and the other Crane servants. Also, there were minor helps: Mr. and Mrs. Crane; Rev. Thomas and Mrs. Beecher, and the Gleasons, half-way down the hill; and the Langdon household at the homestead in Elmira, down in the valley—consisting of one grandmother, and her son Charles and his young family, which young family was of the same vintage as our own.

Mark Twain’s study in its original location at Quarry Farm, about 1874. Today the building is on the campus of Elmira College.

The house stood seven or eight hundred feet above the valley, and thirteen hundred above sea level, and the view commanded the sweep of the valley, with glimpses and flashes of the river winding through it, the wide-spread town, and the blue folds and billows of the receding Pennsylvanian hills beyond. My study stood (and still stands) on a little summit a hundred yards from the house and at a higher elevation. It was octagonal, glazed all around, like a pilot house, with a sun-protection of Venetian blinds; it had a fireplace, contained a table, a chair and a sofa, and was subject to invasions by the children, but was under quarantine against other wandering people. There was a higher summit, with a furnished tent for these. It was seldom uncomfortably warm at the farm, as it overlooked valleys both in front and behind, and the unobstructed breezes kept the air cool. Every summer we left home for The Farm with great enthusiasm as soon as Clara’s birthday solemnities were over. It was always a healthy place. Two of the carriage horses of the early days are hale and serviceable yet, and one of the children’s riding-horses, which they rode in almost primeval times is there still, although he was retired on pension years ago and has been a gentleman loafer ever since. This is “Vix,” named for Col. Waring’s war horse, whose pathetic and beautiful history, as told in the book bearing that title, won the children’s worship, and broke their hearts and made them cry; and two of them lived to mourn again when Waring, a finer hero than even his Vix, laid down his life in rescuing Cuba from her age-long scourge of yellow fever—victor and vanquished in one, for he died of the malady himself.

Aunty Cord was six feet high, and nearly twice as black. She was straight and brawny and strong, and had strong notions about things, and a vigorous eloquence in expressing them if the opposing force were “niggers;” for she had no great opinion of “niggers,” and was not backward about saying so. She spoke the plantation dialect of Maryland, where she had grown up and produced a little family of slaves before the war. For white folks she had flatteries, the common inheritance of servitude, but none for “niggers.” She called Mrs. Clemens “Queen o’ de Magazines,”—which was indefinite but sounded fine, and that was enough for Aunty Cord,—and she was even able to invent grand names for me—at half a dollar each. She was expensive, but then she was the only one I could depend upon for such attentions in that over-fastidious household. She petted the children, of course, and also of course she filled their heads with “nigger” superstitions and damaged their sleep, for she had ghosts and witches in stock, and these were a novelty to the children. According to her gospel, a spider in the heart of an apple must be killed, otherwise bad luck will follow; but spiders with cobwebs under the ceiling must be protected from the housemaid’s broom, it was bad luck to disturb them. Snakes must be killed on sight, even the harmless ones; and the discoverer of a sloughed snake-skin lying in the road was in for all kinds of calamities. The weather, the phases of the moon, uncanny noises, and certain eccentricities of insects, birds, cattle and other creatures all spoke to her in mystic warnings, and kept her in a fussy state of mind the most of the time. But no matter, she was cheerful, inexhaustibly cheerful, her heart was in her laugh and her laugh could shake the hills. Under emotion she had the best gift of strong and simple speech that I have known in any woman except my mother. She told me a striking tale out of her personal experience, once, and I will copy it here—and not in my words but her own. I wrote them down before they were cold.c

a[Mark Twain’s footnote:] One evening in the nursery, when Clara was four or five years old and she and Susy were still occupying cribs, Clara was told it was time to say her prayers. She asked if Susy had said hers, and was told she had. Clara said, “Oh, one’s enough,” and turned over and went to sleep.

By and by, after some months, it was found that Susy had ceased from praying. Upon inquiry it transpired that she had thought the matter out and arrived at the conclusion that it could not be well to trouble God about her small wants, since He knew what they were anyway and could be trusted to reach wise and right decisions concerning them without suggestions from her. She added, tranquilly, “And so I just leave it to Him—He knows.”

While Jean was still a little thing, Katy discovered that she was nightly doing some private praying on her own motion after the perfunctory supplications had been disposed of and the nursery vacated by the mamma and other outsiders. These voluntaries were of a practical sort, and covered several important desires: among them a prompt and permanent remedy for stomach-ache. Katy gave us timely notice, and we went up and listened at the door. Jean described the persecutions of her distemper, and added, with strong feeling: “It comes every day; and oh, dear Jesus, if you ever had it yourself you would reconnize what it is, and just stop it!” “Reconnize” was her largest word, and her favorite. She was the youngest of the children, and came late, comparatively—July 26, 1880.

b[Translations for German profanities: “Almighty God!” “God in Heaven!” “Holy Mother of God!” “Now, thank goodness that’s finished, by God!” “I’d rather be damned in Hell than do that over again!” “O, Lord Jesus, yes, I’ll be right there!” “Oooh, the goddamned soup!”]

c[Mark Twain’s rendering of Mary Ann Cord’s story follows, as “A True Story, Repeated Word for Word as I Heard It”—BG.]