What cruel Laws depress the female Kind,

To humble Cares and servile Tasks confin’d? . . .

That haughty Man, unrival’d and alone,

May boast the World of Science all his own:

As barb’rous Tyrants, to secure their Sway,

Conclude that Ignorance will best obey.

Elizabeth Tollet, ‘Hypatia’, 1724

In A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf wondered what would have happened if William Shakespeare had had an equally gifted sister. Empathetically, she envisaged her imaginary Judith following William’s example and running away to London, only to meet a very different destiny – mockery, pregnancy and a lonely suicide. Woolf explained that Judith was doubly shackled. Most obviously, she lacked her brother’s education, having been taught domestic skills to attract a wealthy husband while William went off to school. More insidiously, Judith had been conditioned from birth into accepting the confining norms of sixteenth-century society, so that the very act of trying to break free would have driven her mad.1

But suppose Newton or Descartes or Darwin had had a clever sister. What would be the fate of a scientific Judith who tried the equivalent of running away to London and knocking at the stage door? Perhaps, as Woolf conjectured, frustrated female geniuses became lonely, half-crazed recluses, mocked and feared as witches with extraordinary powers. But intelligent women could find ways to accommodate their intellectual interests within conventional lives. In wealthy families, some exceptional women employed impoverished scholars for private tuition. More commonly and more importantly, well into the nineteenth century most scientific activity took place in private homes, not in large laboratories or research institutions. This meant that although women were excluded from universities and academic societies, they did become involved in science.2

Most typically, women became engaged at a practical level when a male relative was carrying out research. Their domestic responsibilities already included managing the household, producing and caring for children, and providing the emotional and physical care that liberated their men from daily chores. Exhibiting varying degrees of meekness, they accepted being also co-opted as menial assistants who received no acknowledgement for their work. Using the organisational skills that they had acquired to run the household, sisters, wives and daughters administered the family’s experimental investigations – employing and supervising assistants, buying materials and equipment, marketing medicines and instruments to pay the bills.

Bathsua Makin, a seventeenth-century campaigner for educational reform, pointed out that a housewife’s work demanded expertise in areas that we would now call scientific: ‘To buy Wooll and Flax, to die Scarlet and Purple, requires skill in Natural Philosophy. To consider a Field, the quantity and quality, requires knowledge in Geometry. To plant a Vineyard, requires understanding in Husbandry: She could not Merchandise, without knowledge in Arithmetick: She could not Govern so great a Family well, without knowledge in Politicks and Oeconomicks: She could not look well to the wayes of her Houshold, except she understood Physick and Chirurgery.’3

Wives, sisters and patrons played indispensable parts in achieving the results for which their men became renowned. Some women taught themselves foreign languages, so that they could keep their husbands or brothers up-to-date with the latest scientific results from abroad. Others suggested new theoretical interpretations, collected botanical and geological specimens, or set up classification schemes. Women were often responsible for collating, editing, illustrating and publishing books that inevitably appeared under the male partner’s name. They also undertook the vital tasks of translating and interpreting complicated ideas. By writing lucid explanations, they ensured that scientific knowledge became accessible to everyone – future scientists as well as the general public.

Delving back through the centuries, feminist historians have rewritten women’s lives according to modern standards of equality and liberation. This anachronistic approach can involve much wishful thinking, because these women behaved and wrote in ways that simply do not conform with today’s ideals of independence and equality. Many women of the past seem almost to be colluding in their own oppression, themselves accepting that they could not fulfil the same functions as their husbands, sons and brothers. Even those who did rail against their limited opportunities generally believed that, physically and psychologically, they were suited to different work from men.

Aristotle’s ideas about bodies and minds prevailed well into the seventeenth century and even beyond. Women were regarded as inferior versions of men, placed beneath them on the great chain of being that stretched from the lowest organisms up towards the angels and God. Men were like the sun – hot and dry. But women resembled the cold, moist moon, so that their brains were less capable of rational thought. Long after these ancient models had been overturned, new physical criteria – anatomical differences, hormonal systems – provided new rationales for keeping women below men in the intellectual hierarchy.4

Time after time, people interested in maintaining the status quo spelt out the appropriate roles for men and women. In an eighteenth-century stage comedy, Lady Science confesses, ‘I am justly made a Fool of, for aiming to be a Philosopher – I ought to suffer like Phæton, for affecting to move into a Sphere that did not belong to me.’ The dastardly Gainlove rejects Lady Science and marries her daughter instead, because, he insists, ‘the Dressing-Room, not the Study, is the Lady’s Province – and a Woman makes as ridiculous a Figure, poring over Globes, or thro’ a Telescope, as a Man would with a Pair of Preservers mending Lace’.5

Lady Science and her erstwhile suitor bisected society into separate spheres: men studying science, women learning domestic skills; men exploring the outside world, women confined to hearth and home. This simplistic model – separate spheres – dominates how we perceive life in earlier centuries. In another satirical play about learned women, an angry father can hardly tolerate that he has ‘a Daughter run mad after Philosophy, I’ll ne’er suffer it in the Rage I am in; I’ll throw all the Books and Mathematical Instruments out of the Window’.6 This was, of course, a hollow threat – the audience was not expected to believe that he would really treat her things that way. Rhetorical claims are often exaggerated, and there was no shortage of frightened but dogmatic protests that women were incapable of engaging in such an unsuitable activity as natural philosophy.

Fig. 4 Margaret Cavendish (Duchess of Newcastle) and her family. Frontispiece of Margaret Cavendish, Natures Pictures Drawn by Fancies Pencil to the Life (London, for J. Martin and J. Allestyre, 1656); original by Abraham van Diepenbeke, engraved by Peter Clouwet.

This propaganda campaign still distorts how we view the past. But in fact women strongly affected the development of scientific ideas and their integration within society. If we peer behind the front door of scientific households, a different picture appears. Figure 4 shows the Newcastle family at dinner. Margaret Cavendish and her husband the Duke of Newcastle sit at the right, their heads crowned with laurel wreaths. This picture was doctored for publication. Here the Duke of Newcastle is speaking, while his wife listens mutely at his side. In the original version, Cavendish was holding up her hand for attention as she addressed the party. In private settings, women enjoyed far more power than in the outside world.7

In the middle of the seventeenth century, the Newcastle couple formed the nucleus of an important intellectual circle. Both strong royalists, their moves between Paris and London depended on the English political situation. They invited many famous scholars, including René Descartes and Thomas Hobbes, to share their meals and discuss the latest philosophical and scientific ideas. Unlike now, intellectual debates took place in people’s homes rather than in official institutions such as universities or societies. Margaret Cavendish could participate in the learned conversations that were taking place in the privacy of her dining-room, even though she did not always have the courage to venture her own opinions.

Cavendish dispensed useful advice to women who were frustrated by their conventional education: choose the right man. She had married into one of England’s richest families. In Figure 4, the fine wood panelling and armorial crest over the mantelpiece advertise that she lived in stately surroundings; a servant is opening the window to counteract the heat from the large fire. Her husband, like many seventeenth-century Cambridge graduates, knew far more about the rules of hunting than the laws of nature, but he enjoyed supporting gifted scholars. He encouraged his wife’s intellectual interests, financed the publication of her books, and conveniently had a well-educated brother who taught her natural philosophy.8

Some scientific women were born into rich families; others, like Cavendish, chose husbands whose interests meshed with their own, so that they could study natural philosophy and collaborate in experimental investigations. Unlike men, these women only rarely left published texts behind, but their letters and personal notebooks demonstrate how actively they engaged in scientific and philosophical controversies of the time. 9 Katherine Jones (Lady Ranelagh) lived with her brother, the famous chemist Robert Boyle, for thirty years. She shared her brother’s laboratory equipment and engaged in debates with their visitors, both men and women. She belonged to an intellectual network of wealthy women who experimented and wrote inside their own homes, women like Mary Evelyn who experimented alongside her husband John, the famous diarist, and gradually took over the record-keeping.10

These wealthy female aristocrats were generally banned from venturing out into the academic world, but some of them converted their homes and stately mansions into discussion centres. Here they could debate with Europe’s most distinguished intellectuals and participate in the extensive correspondence network that bonded together the Republic of Letters, the international intellectual community which transcended geographical boundaries. Some of them employed scholars as teachers or invited them as long-stay house guests; this meant that learned protégés relied on women’s patronage for survival. John Aubrey reported that the wealthy Countess of Pembroke made sure ‘Wilton house was like a College, there were so many learned and ingeniose persons. She was the greatest patronesse of witt and learning of any lady in her time. She was a great chemist and spent yearly a great deale in that study. She kept for her laborator in the house Adrian Gilbert . . . She also gave an honourable yearly pension to Dr Mouffett, who hath writt a booke De insectis. Also one Boston, a good chymist . . .’11

Just like their brothers and husbands, wealthy women could choose to support scholars financially. To return the debt, authors paid their patrons lavish compliments in printed books, and thus advertised this female contribution to the sciences. In the dedication for his book on comets, the musician Charles Burney wrote an obsequious tribute to the Countess of Pembroke (a later one than John Aubrey’s) praising her enthusiasm for astronomy. Another strategy was to publish texts in the form of letters between a learned natural philosopher and a distinguished woman. Leonhard Euler’s two volumes of simplified science were addressed to a German princess and sold exceptionally well throughout Europe; for his imaginary correspondent, the Swiss geological historian Jean de Luc chose his English patron, Queen Charlotte.

During the eighteenth century, it became more common for intellectual women to gather together in discussion groups, such as the bluestockings in London. Especially in France, women hosted weekly meetings that were also attended by men, and where the latest scientific results were often discussed along with new literature and political scandals. Although many of these women have been forgotten, they exerted considerable power. Elizabeth Ferrand is now unknown, yet her salon attracted Denis Diderot and other eminent Parisian men of letters, such as the well-known philosopher Étienne Bonnot de Condillac. According to malicious gossips, Ferrand was a dour humourless woman, yet they all paid tribute to her mathematical ability. Art connoisseurs singled out for praise her portrait, which was first displayed in the 1753 Louvre exhibition and pays tribute to her scientific expertise – momentarily distracted from her studies, she gazes out at the viewer, a large volume on Newtonian physics propped up like a Bible beside her. Condillac did have the grace to acknowledge that her ideas lay at the heart of his Treatise on the Sensations – but only his name appears on the title-page.12

Other wealthy women indulged their fascination with science by building up large collections of shells, minerals and pressed flowers. Sarah Sophia Banks was a collecting addict, and she possessed the same passion for natural history as her brother Joseph, who was President of the Royal Society for more than forty years. Perhaps they both inherited their enthusiasm from their mother Sarah – the botanical herbal she kept in her dressing-room was the first serious book ever read by Joseph, who was not a brilliant scholar. His younger sister Sarah Sophia, on the other hand, seems to have been a frustrated academic. As an adult, she was ridiculed for stuffing her pockets with books so that she would never be short of something to read. Had she been a man, her inelegant clothes and studious demeanour would have been praised as signs of her intellectual aptitude. Instead, she was mocked for lacking the appropriate feminine graces. Joseph Banks did marry, but he seems to have attached more importance to Sarah Sophia, who lived with the couple until she died. The brother and sister formed an inseparable scientific partnership. Although she could not participate in his life at the Royal Society and London’s gentlemanly clubs, she was intimately involved in the scientific meetings and discussions that took place in their central Soho home.13

These women’s activities were not just idiosyncratic pastimes – building up large collections of samples from all over the world was vital for classifying the exploding number of discoveries. The Duchess of Portland (as a later Margaret Cavendish is usually called) started her enormous collection of plants, minerals and fossils when James Cook gave her some shells after one of his voyages to Australia. The auction after her death lasted for thirty-eight days, when the curiosities she had accumulated were divided up between eminent bidders, including the surgeon William Hunter. Another important yet forgotten woman collector was Madame Dubois-Jourdain – even her Christian name seems to have disappeared from the records as her identity became subsumed into her husband’s. Her husband was attached to the French royal household, and Dubois-Jourdain studied physics and chemistry so that she could catalogue her large collection of minerals. She became linked in to an extensive correspondence network of mineralogists, and enthusiasts came to admire her cabinet in her Paris home so that they could exchange and discuss rare rocks with her. By the time that Dubois-Jourdain died, she had acquired many specimens that were scientifically as well as financially valuable.14

But these were the privileged few. Scholars have been able to reconstruct their lives – if only partially – by examining family records, diaries and letters. All over Europe, similar conversational scenes to Cavendish’s were taking place in less wealthy households, although it is even more difficult to learn about these women’s activities in any detail. Because experimental natural philosophy was a relatively new activity, men who worked at home not only relied on their womenfolk’s cooperation, but also had to negotiate ways of integrating scientific projects within the daily household routine. Arguments about the latest scientific ideas were thrashed out around the dinner table, in mixed groups that gave women the opportunity to listen and perhaps contribute their own ideas. Women were actively involved in the family’s experiments and could participate in discussions about their results.15

Very little information about these domestic situations has survived, so it is impossible to discover how many women collaborated in experimental research and took part in dinner-party debates. This female participation was undoubtedly far greater than old-fashioned accounts suggest. For one thing, experiments often require more than one participant: astronomers dictate their observations while looking through a telescope; chemists cannot simultaneously pour in reagents and record measurements; physiologists need several hands to hold down specimens and manipulate instruments.

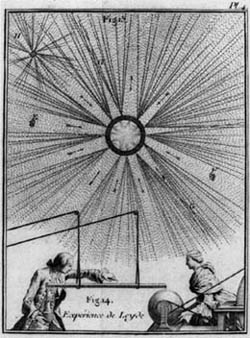

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, before being a scientist had become a professional career option, experimenters struggled to earn a living. The women in the household provided a free source of labour, and many brief – but solid – pieces of evidence testify to their involvement, such as passing references in letters or the occasional grateful tribute in a preface. Figure 5 is a rare illustration of a woman participating in an experiment. The French lecturer Jean Nollet earned money by performing demonstrations designed to enthral as well as instruct his audience. When electricity became the most fashionable scientific entertainment, Nollet advertised his new machine, which needed a helper to turn the handle. Rarely even mentioned, such assistants are normally unidentifiable, indicated only symbolically by a disembodied hand in a frilly white cuff. However, Nollet’s picture makes it clear that his invisible assistant was a woman (although she is not referred to in the text).

Fig. 5 Jean Nollet and his female assistant. J. A. Nollet, Essai sur l’Électricité des Corps (Paris, 1746).

Scientific experimenters, lecturers and entrepreneurs lived and worked in the same place. Modern laboratories and factories are now completely separated from people’s homes, but the whole family used to be involved in running businesses. When the engineer James Watt was away from home, he left his first wife Peggy in charge of their instrument trade, and later wrote technical letters to his second wife Annie, knowing that she had learned chemistry during her upbringing in a linen-bleaching family. Watt’s friend William Withering, a famous botanist and physician, instructed his children to collect plants while they were out walking, and then got the French governess to draw them for him – although his daughter reported sabotaging science by painting patterns on fungi to fool him. Withering set himself up as an expert who taught science to women through correspondence, yet he owed his fame as a heart specialist to an elderly and uneducated woman’s traditional herbal remedies.16

Many scientific experimenters expected the women around them to work. One of Newton’s enemies, the Royal Astronomer John Flamsteed, recruited his wife Margaret to study alongside his paid apprentices and help him make observations. Her own notebook reveals her mathematical proficiency and the range of tasks she had to cope with. After her husband’s death, Margaret Flamsteed superintended the publication of his star catalogue, which remained a major reference source for more than a hundred years.17

The French astronomer Joseph Lalande also relied on women mathematicians – including his own niece by marriage – and was especially close to Nicole-Reine Lepaute. She was married to the royal clock-maker, and had already computed detailed tables for his experiments on pendulums. Lalande enrolled Lepaute to help predict the precise date that Halley’s comet would return in the mid-eighteenth century, and for months on end she sat at a table with Lalande carrying out long and complicated calculations. Lepaute was constantly engaged in astronomical mathematics for around twenty-five years, but – like other female calculators – her work was not always acknowledged by the men who depended on it. Lalande himself did pay tribute to female astronomers, but excused the neglect of his colleagues by blaming the jealousy of other women who could not bear to be outclassed.18

John Desaguliers, Newton’s favoured assistant at the Royal Society, converted his home into a scientific school. Apparatus was stashed all over their Westminster house – instruments in various stages of completion, piles of unsold books, and bulky demonstration equipment including an eight-foot-wide bellows and a working steam-engine. When Desaguliers went on his frequent international lecturing tours, his wife Joanna was left behind to run the school as well as caring for the paying boarders. Small wonder that five of her seven children died in infancy – and who, one wonders, took over when he was laid up every winter with attacks of gout?19

As well as organising homes, children and businesses, women were involved in developing new techniques. When the factory owner Josiah Wedgwood tried out different methods of firing and colouring pottery, his wife Sally helped him record the results. He explained to his business partner how he enabled her to go on working with him, even though she was already overburdened with household affairs – including their three-month-old daughter: ‘Sally is my chief helpmate in this as well as other things, and that she may not be hurried by having too many Irons in the fire as the phrase is I have ordered the spinning wheel into the Lumber room.’20

During his trials of different types of gases, the chemist Joseph Priestley made his wife Mary responsible for keeping his experimental mice warm on the mantelpiece. There were, of course, hitches. Mary was disconcerted to discover chemical flasks and minerals stowed away in her travelling trunk of neatly packed clothes, and Joseph was furious when their daughter carefully washed out all his laboratory bottles.21 Tempting to laugh – but these intimate details of domestic disruption, so painfully familiar and imaginable, vividly convey the realities of early scientific research. Women are absent from the written reports, but in reality they were very much present.

Official accounts of Soviet Russia avoided mentioning Josef Stalin. In contrast, women have not been written out of the history of science: they have never been written in. This neglect is part of the large-scale omission of women from the historical record, but there is no simple way of rectifying the situation. Feminists have chosen several different routes to restore these vanished women to visibility. In the late 1970s, the artist Judy Chicago shocked conservative critics by exhibiting an imaginary dinner party between forgotten women from the past. She painted the floor with the names of 999 high-achieving women, and designed individual place settings around a triangular table, arranging her female guests in a chronological loop so that Virginia Woolf sat next to an ancient goddess.22

But celebrating people just because they are women suggests that they are bound together by some essential quality of womanhood which transcends the barriers of time and culture. How could a modern overworked doctor communicate with a refined Renaissance lady of leisure – how would she argue with a woman who believed that she possessed a cold, soft brain incapable of intellectual reasoning, and a womb that wandered round her body causing all sorts of mysterious disorders? How could a company director explain her professional pride to a wife whose whole upbringing had been dedicated towards preparation for marriage and financial security as she was transferred from father to husband? How could a university scientist discuss her research with a well-educated aristocrat who insisted that the Bible was the major source of knowledge about the universe, and that God had created the world at 9 am on 23 October 4004 BC?23

Too much sympathy for these neglected women can be counterproductive. Emphasising the difficulties faced by intelligent women can convert them into self-sacrificial martyrs. In well-intentioned pastiches of the past, scientific women emerge as cardboard cutouts – the selfless helpmate, the source of inspiration, the dedicated assistant who sacrifices everything for the sake of her man and the cause of science. On the other hand, overcompensation – glorifying women as lone pioneers, as unrecognised geniuses – also has its drawbacks. Despite having to struggle against huge disadvantages, such arguments run, some women did contribute to scientific progress. If only they had biologically been men, one can almost hear their biographers sigh, then their true brilliance would have been recognised. Prominent examples include Aspasia of Miletus, Hypatia of Alexandria and Hildegard of Bingen. All exceptional women, without doubt, but it is misleading to celebrate them as suppressed scientists. Modern science bears little resemblance to intellectual pursuits of ancient Greece, fifth-century Egypt or Benedictine monasteries. These women certainly deserve to be honoured, but only within the framework of their own contemporaries.24

There is no point in distorting women’s importance by exaggerating their activities. Singling women out as geniuses is as misleading as suppressing their existence. Standard caricatures of women – the docile assistant, the doting but ignorant source of inspiration – are certainly demeaning descriptions. But substituting yet another stereotype – the lonely, unappreciated pioneer – gets no nearer to understanding women’s status in science and the lives they led. Making women from the past into brilliant proto-scientists is just creating a female version of solitary male geniuses. More realistic models are needed for both the sexes.

Trying to squeeze women into conventional stereotypes makes it impossible to reconstruct how they felt about their own lives, what they themselves regarded as their significant achievements. Part of the problem is finding an appropriate style for telling women’s lives. As the famous clerihew quips: ‘Geography is about maps, / But Biography is about chaps.’ There is no established format for integrating a woman’s personal and professional experiences within the covers of a single book. Woolf complained that too much history is about wars, and too many biographies are about men. Her own father had narrated George Eliot’s career as though this female novelist were a purely intellectual being: through selective pruning, he effectively eliminated her tumultuous emotional existence. Old-fashioned biographical conventions force women’s lives to follow male scripts by emphasising publicly acclaimed successes, rather than inner feelings and personal relationships.25

This problem is even more acute in scientific biographies. Until recently, words like physicist, philosopher and mathematician automatically signified a man, so that scientific women were seen as freakish intruders into a male domain. Sympathetic biographers worry that including emotional aspects of a woman’s life will reinforce all those existing prejudices that women do not belong in the cold world of scientific research. Men as well as women are affected by their family and financial worries, their loves and losses, joys and despairs, yet the ethos of science demands that its practitioners perform with icy detachment. This ideal clashes with stereotypes of sensitive nurturing women and female scientists have been made to feel pariahs twice over – not only as invaders into a hard masculine world, but also as outlaws excluded from cosy feminine circles. They were parodied as atypical oddities who had renounced all claims to normal female interests, yet were unable to participate fully in scientific life.

Take the case of Marie Curie. Her daughter Eve portrayed her as a saintly mother, an exemplary martyr who dedicated herself to her family as well as to science. Like many other biographers, Eve glossed over the scandal of Marie’s affair with a married colleague. Female scientists are supposed to be asexual, abnormal women, and Marie Curie is always shown wearing plain clothes and a humourless expression. Marie and her husband Pierre were complementary scientific partners – she was a physicist and he was a chemist; she was outgoing and energetic, he was a nervous recluse whose behaviour would nowadays lead to a diagnosis of attention deficit disorder. Nevertheless, in the romanticised versions of their lives, it is Marie who appears as an obsessive chemist. Her success is attributed not to her intellectual originality but to a daily grind of methodically sifting through tons of pitchblende – the scientific equivalent of mundane cookery. Marie Curie has been converted into an icon for ambitious young women to emulate, yet this image of a badly dressed drudge warns female students that they must abandon all prospects of normality if they wish to compete in the scientific race.26

A better way of highlighting the significance of women in science is to tackle conventional history head-on and rewrite it. Science’s history is about far more than equations, instruments and great men – it is about understanding how a huge range of practical as well as scholarly activities became the foundations of our scientific and technological society. Women played vital roles in that transformation.

There is no right way to create the past. After the Second World War, optimistic campaigners seized on science as a replacement for Christianity, as a secular religion that would unite the nations to bring peace and progress. They rewrote European history, placing the birth of modern society not in the artistic Renaissance, but in a seventeenth-century Scientific Revolution – a term that had only been introduced in the 1930s. For these scientific historians, science meant ideas: they were interested in abstract theories about gravity and the structure of the universe. They divorced science from daily events and world affairs, and studied the scholarly debates between leisured academics and clerics. Concentrating on physics and astronomy, they told science as an epic success story, a triumphant march towards incontrovertible truth led by great heroes such as Galileo, Kepler and Newton.

Subsequent generations have brought new problems, new questions, new ways of writing science’s history. The Scientific Revolution, seen as so important for decades, is being ironed out of existence. Historians now emphasise continuity rather than change. They are challenging the story that science erupted suddenly in early modern Europe and are replacing it with different versions of the past. Many experts see a gradual transition around the turn of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when modern scientific disciplines were being created, the financial rewards of research were being recognised, and research was starting to move out of people’s private homes into laboratories, museums and hospitals. After all, it was only in the early nineteenth century (1833, to be precise) that the word ‘scientist’ was invented – a new term to identify a new social category. Before then, investigations that we would call scientific were carried out by skilled artisans and by a vanished group labelled natural philosophers, who were mostly wealthy gentlemen trying to learn more about God by studying the natural world.

Instead of focusing exclusively on great minds and great ideas, historians are now more interested in examining how science has entered everyday life. They are investigating the activities of people who did play vital roles in science’s history, but who worked outside learned societies or universities. These unrecognised experts included skilled artisans who made surveying instruments or calculated the trajectories of cannon balls, and practical people – navigators, herbalists, miners – who possessed valuable stores of knowledge unknown to closeted scholars. In romanticised versions of the past, science progresses in uneven leaps as solitary geniuses make momentous discoveries in their disinterested search for truth. Other accounts – aiming to be more realistic – recognise that scientific researchers are human beings prompted by mundane concerns, including money and fame as well as industrial, medical and military requirements. And some writers have introduced women into science’s past.27

In conventional versions of science’s history, women are either absent, or else feature as useful appendages of a famous man – the admiring wife, the helpful sister, the docile pupil. This is partly because stories about science have been written like schoolboy adventure novels. Bristling with the vocabulary of warfare and competitive sport, they feature scholarly gladiators triumphantly battling against the forces of nature. Heroic solitary explorers climb intellectual mountains, valiant discoverers race against one another to win a Nobel prize, intrepid teams celebrate advances and breakthroughs. Such glorified visions of the past are updated versions of classical myths. Stepping into the sandals of the gods, scientists have become the super-heroes of the modern age.28

When historians focus on famous individuals, they leave out many vital people who made science central to everyday life. Science’s intellectual class system rates the achievements of gentlemen far higher than those of artisans and women. What about the technicians and administrators who made instruments work, recorded observations, collected and prepared specimens, catalogued results, organised the laboratory? The reputations of many celebrated men were built on the dangerous exploits and patient searches of countless explorers, collectors and classifiers. And surely tribute should be paid to those who provided financial support, or were knowledgeable enough to make constructive criticisms, check experimental readings and proofread manuscripts? Retrieving these invisible assistants – male and female – gives a far more realistic picture of how science was actually carried out.29

Another problem with heroic histories is that they isolate scientific achievements from the rest of society. As well as intellectual shifts, vast social transformations were also crucial for establishing the foundations of modern science. Scientific knowledge now dominates popular media as well as educational syllabuses, but this has only happened because teachers, editors, museum curators, translators and illustrators enabled other people to learn about new results and theories. Without them, science would have remained an esoteric scholarly pursuit, reserved for the privileged few. Many of these forgotten people were women.

Traditional histories of science focus on discoveries and inventions, almost invariably made by men who are elevated to the status of great heroes. Such models of progress may be appealing, but they distort the past by leaving out important parts of the story. Science cannot advance without a shared fund of knowledge. It is essential to make specialised publications accessible to wider audiences, both at home and abroad. Scientific progress depends on the existence of solid education systems, so that new generations of researchers can build on the results of their predecessors. Understanding how science has become so important means looking not only at its successes, but at how its achievements are perceived and disseminated. Because women were excluded from universities, scholarly societies and laboratories, they could not make the same contributions towards science as men. However, their work in education was vital for science’s growth.

Science is not just a final product, such as a theorem, chemical or instrument, but is an integral component of society. Industry, business, warfare, government, medicine – they all depend on science and also affect how it develops. To understand how science came to form the backbone of our modern world, we need to describe not only what happened inside laboratories and studies, but also what happened outside.30 Women as well as men have participated in the collective endeavour that brought about science’s ubiquitous presence. Scientific history is not only about knowledge itself. It is also about how that knowledge was reached, taught and used. Broadening what counts as science’s history entails recognising and crediting women’s involvement.

Women made different contributions from men – but different need not mean insignificant. Women simply could not operate in the same way as men. They were educated separately, were seen as being physically and psychologically different, and were expected to assume domestic and educational responsibilities. In old-fashioned versions of science’s history, great men stride along the road to truth, their achievements along the way marked by milestones of famous discoveries. Like lower-class men, women are inevitably excluded from these models of the past – rather like all those manly Victorian explorers who supposedly climbed to the tops of mountain peaks or reached remote river sources without the assistance of local guides and porters. Too many people have been air-brushed out from our visions of the past. Understanding how and why science has become so important means learning about artisans and assistants as well as about wealthy gentlemen, about science’s integration into society as well as about esoteric theories and experiments – and about women as well as about men.

Without women, science would have developed very differently. For one thing, many important experiments would never have been started, let alone finished, without the unrecorded cooperation of wives, sisters and daughters. If women had not silently taken over the task, observations would have remained uncatalogued, collections would not have been classified, specimens would not have been illustrated. Without their female critics, many scientific books would be less polished, and some of them would not even have been written; others would have languished as piles of papers in a drawer, waiting for an editor to collate, organise and publish them. So many men must have presented collaborative endeavours as their own. As an English scientist wrote in a letter to his wife, ‘Had our friend Mrs Somerville [a nineteenth-century physicist] been married to La Place or some other mathematician, we would never have heard of her work. She would have merged it with her husband’s, and passed it off as his.’31

Just as significantly, women were vital for establishing effective channels of communication. To make science useful, ideas must travel in several directions, not just outwards from an elite core of specialists. Experimenters need to know which problems need solving, which lines of investigation meet public approval, which approaches would distinguish them from their competitors. Science is integral to modern society because a great deal of collective effort was involved in advertising its benefits and persuading governments and private investors to provide financial backing. Female educators often did far more than water down complicated ideas: they provided new interpretations, corrected mistakes, clarified obscure points and translated foreign books.

Without women, less would be known by far fewer people, and science would have eventually ground to a standstill. By translating important scientific texts into foreign languages, women enabled results to be rapidly transmitted between one country and another. They also engaged in an even more important type of translation – interpreting complex theories and translating them into straightforward explanations that could be understood not just by students, but also by the politicians and industrialists who direct the path of research through funding. Chauvinists still joke about women’s (alleged) inability to tackle mathematics and science. In reality, women were crucial for enabling the spread of science, technology and medicine into many different areas. Without their participation, our lives today would have been very different.

If the past is a foreign country, then Pandora’s Breeches is a new type of guide. Remapping the entire territory in a single trip – rewriting the whole of science’s history in one book – would be an impossible project. Rather than setting off immediately into the unknown, Pandora’s Breeches starts from the security of the familiar, but suggests different pathways to follow. Instead of completely abandoning the well-known landmarks of the past, those famous men and their heroic discoveries, this book examines some of them from other angles. By telling new stories about old characters, it reveals different ways in which women have affected the development of science.

One way of thinking about Pandora’s Breeches is to consider Figure 6, an imaginary man-woman scientific couple that symbolises the real-life pairs presented in this book. Writing under a pseudonym, the caricature publisher Samuel Fores produced this image as part of his invective against male midwives, who were much in demand by fashionable mothers at the end of the eighteenth century. Fores wrote a venomous booklet designed to expose ‘their cunning, indecent and cruel practices’ and encourage women to withstand these upstarts taking over their traditional area of expertise. (No accident that a man should be somewhat unexpectedly defending the rights of female experts – Fores also provided helpful hints for husbands who were worried about the intentions of these male invaders entering their wives’ boudoirs.)

First published in 1793, this print has been interpreted in several ways – much as Pandora’s Breeches rewrites the relationship between real scientific partners from the past. Most obviously, Fores’s picture compares two stereotypes. On one side stands the female midwife who points to the blazing fire heating up a pan of water. Her bright informal clothes and the flowered floor-covering send out comforting signals that birth is a natural event, when the mother will be eased through labour by experienced women clustered around her in the seclusion of her own room at home. The sharp dividing line sears down the page like a scalpel-cut. On its other side, the man’s dark tailored jacket radiates authority and his aggressive instruments signal the pain ahead, when cold metal will grab the fragile baby and wrench it out.32

Men who ventured into women’s traditional spheres were regarded with as much hostility as women who dared to engage in science. Over two centuries later, the medical management of childbirth is still being challenged. This bisected figure also symbolises angry conflicts between historians with different views about interpreting the past. For those with faith in scientific progress, male midwives represent the triumph of clinical experts over gin-swilling, ignorant women like Charles Dickens’s Sairey Gamp. Many feminists have disagreed. Far better, they insist, to encourage natural birth than artificial intervention, to rely on women’s innate instincts than on icy expertise and metallic instruments. In addition, they continue, these male intruders elbowed women out of their rightful domain – men excluded women from the new medical specialities and forced them into subordinate positions below male professionals.

Fig. 6 A Man-Mid-Wife. John Blunt (Samuel Fores), frontispiece of his Man-Midwifery Dissected (1783), hand-coloured etching.

The original hand-written caption reads:

‘A man-mid-wife or a newly discover’d animal, not Known in Buffon’s time; for a more full description of the Monster, see, an ingenious book, lately published price 3/6 entitled, Man-Midwifery dissected, containing a Variety of well authenticated cases elucidating this animals Propensities to crudity & indecency sold by the publisher of this Print who has presented the Author with the Above for a Frontispiece to his Book.’

All these arguments portray women as hapless victims with little control over their own fate. Yet another way of interpreting this picture restores women to a position of power. Midwifery services had to be paid for, and wealthy women preferred to employ trained men with their instruments, instead of traditional female attendants. Male midwives became popular through female choice. Reinterpreted, Fores’s dichotomous image proclaims the authority of women, not their subservience.33

There were many real-life pairs of scientific women and men – sisters and brothers, wives and husbands, patrons and protégés. Like reinterpreting Fores’s imaginary duo, redrawing their linked relationships gives women a powerful presence. At the most basic level, many men would simply have been unable to cope without the emotional support of a companion who was sufficiently educated and intelligent to discuss setbacks. It is too easy to denigrate these countless women by dismissing them with empty clichés – handmaidens of science, or the power behind the throne.

Even towards the end of the nineteenth century, some scientists brought their research right into the home, traditionally a female realm. This meant that even women with no scientific training inevitably became involved. Day after day Charles Darwin’s wife Emma nursed him through bouts of sickness, probably psychosomatic in origin, yet painfully disabling. She warded off unwelcome visitors, listened patiently through his moments of self-doubt, and inwardly sighed with relief when he found a new problem to consume his attention and hence calm his spirit. This fragile yet manipulative scientist converted Emma into a mother-figure, whimpering, ‘Oh Mammy I do long to be with you & under your protection for then I feel safe.’ In the evenings, they discussed his work together, and he recruited further women – other scientists’ wives, Emma’s friends – as his unofficial editorial team. Darwin’s great book on evolution was a collective effort whose success depended not only on contributions from countless collectors and naturalists, but also on the female workers who made his ideas comprehensible.34

Darwin’s science occupied the entire household. When one of their children visited a friend, he politely enquired where the barnacle dissecting room was – his father’s unusual obsession was this boy’s daily normality. There was no chance for Emma Darwin to retreat into private domesticity. In a typical project to investigate a carnivorous plant’s feeding habits, Darwin took over one of the kitchen shelves as a laboratory and scoured the house for flies, spiders and bits of bathroom sponge. He used their children and pets as research subjects, sketching their expressions and making scientific notes on their rate of development; and he enrolled the young mothers in his extended family as research assistants to report on their own babies’ behaviour.35

Despite this domination, Charles Darwin evidently saw himself as a liberated husband, comparing himself favourably with their friend Charles Lyell. Lyell, a lawyer who became famous as a geologist, effectively represented two people’s work as one by relying on his wife Mary for scientific as well as emotional support. Even during their engagement, he coerced her into studying geology and learning German so that she would be useful to him later. He converted their honeymoon into a scientific field trip, and throughout their childless married life exploited her skills so that he could pursue a successful and productive career. She compensated for his deficiencies in several areas: she read to him for hours on end because of his poor eyesight, she translated foreign articles that he could not understand, she illustrated his books because he could not draw, she edited his writing to ensure it was stylishly written and error-free, she became more expert than him on conchology, and she classified his specimens to save him the trouble. She even recruited her maid: ‘I have taught Antonia to kill snails and clean out the shells and she is very expert.’36

Information exists about women like Emma Darwin and Mary Lyell because their husbands were famous scientists and they were born into wealthy families. Many earlier women must have had similar experiences, although reconstructing their lives in any detail is much more difficult. The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were crucial for the explosive growth of science during the Victorian era, yet less evidence of these concealed women survives.

It is hard to get away from heroic versions of history. For one thing, our vision of the past, our internal map, is structured by celebrated names and events – Galileo, Newton, Darwin, Einstein. Simply throwing away an old map is not the best way of assessing the value of a new one. Rather than setting out with a totally blank sheet, it is easier to navigate by keeping some familiar landmarks. In addition, writing new stories demands reassessing the evidence, and since historical records are generally clustered around prominent people, that means starting with those eminent men about whom we have more information.

So as a first step in rewriting scientific history, Pandora’s Breeches concentrates on a small selection of women who were linked to famous men in different ways. These were unusual women, to be sure. But in traditional versions of science’s past, even their attainments have been eclipsed by the auras radiating from men. Retelling the stories of selected man–woman partnerships does more than just restore these unusual women’s lives to visibility. Breaking away from conventional history to give women more prominence reveals the activities, opinions and aspirations of other individuals about whom we have little specific information. For all the women who left behind tangible traces, there must have been many more who have disappeared from the archives. Evidence about women’s lives is hard to retrieve, but their ghostly presence in the surviving records yields tantalising hints of their very substantial real-life existence.37