The whole duty of the wife is referred to two heads. The first is to acknowledge her inferiority: the next, to carry her selfe as inferiour . . . If euer thou purpose to be a good wife, and to liue comfortably, set downe this with thy self. Mine husband is my superiour, my better; he hath authority and rule ouer mee: Nature hath giuen it him, hauing framed our bodies to tenderness, mens to more hardnesse. God hath giuen it him, saying to our first mother, Euah, Thy desire shall be subject to him, and hee shall rule ouer thee . . . Though my sinne hath made my place tedious, yet I will confesse the truth, Mine husband is my superiour, my better.

William Whately, The Bride Bush, 1617

Euphrosyne (Figure 18) was brought up in a world lit by candles and oil-lamps, so that the rhythms of her daily life were governed by the sun rather than by clocks. As the servant John turned the handle of her brother’s electrical machine, Euphrosyne was captivated by the mysterious lights that seemed to materialise out of thin air as if by magic. It is still exciting to sit like her in a darkened room and watch the globe of an electrical machine start to shimmer. For Euphrosyne, who had never before seen electrical sparks and glows, it must have been a quite extraordinary experience.

‘On my word, Cleonicus,’ she exclaimed, ‘if you were to shew these Experiments in some Countries, with a black Rod in your Hand, and a three-corner’d Cap, and a rusty furred Gown on, they would certainly take you for a Conjurer, and believe you had the Art of dealing with the Devil, beyond even Sydrophel himself; for they could not possibly believe such Things were to be done by the Power of Nature, as you now shew by this small machine.’1 Speaking through Euphrosyne, the teacher Benjamin Martin was hammering home the message that natural philosophers – especially English ones – relied on reason, not on magic, for their performances. Witchcraft and wizardry might, Euphrosyne marvelled, be good enough as explanations for ignorant people, but not for those illuminated by the electric light of Enlightenment rationality.

Euphrosyne’s Sydrophel was a well-known fictional sorcerer, but many of her readers would immediately have thought of John Dee, an Elizabethan natural philosopher with a notorious reputation. Modern scholars present him as an eminent mathematician, but he was vilified by his enemies as ‘Doctor Dee the great Conjurer’. This blackwashing process intensified during the following centuries, and in Euphrosyne’s time, Dee was renowned as an outrageous charlatan of a bygone age. By exaggerating some aspects of Dee’s life, propagandists for the power of reason cast him as an esoteric visionary, and so made their own arguments seem vastly preferable. Dee still symbolises the dark forces of arcane magic which have been swept away by scientific experiment and rationality. But magic sells well, and Dee’s story can be romanticised by emphasising appealing ingredients, especially his conversations with angels . . .

John Dee was Queen Elizabeth’s ‘angel conjuror’ who wore a black skullcap and ‘put a hex on the Spanish armada which is why there was bad weather and England won.’2 The early part of his life gave no clear indication of this extraordinary future. He read mathematics and astronomy at Cambridge, where he became one of the first Fellows of Trinity College; he also studied abroad, and lectured on Euclid and geometry at the Sorbonne in Paris. Dee even became a country clergyman – yet was this perhaps a cover for more arcane pursuits?

After turning down offers of university lectureships at Paris and Oxford, Dee embarked on an unorthodox way of earning his living – setting up a laboratory within his own home and relying on wealthy patrons for support. He openly rebelled against the traditional scholarship of the universities. Instead of studying Aristotle, Dee turned to mathematics and experiments and chose to investigate the natural world. Rather than remaining in the old-fashioned English university system, Dee preferred to explore the exciting subjects being taught by Europe’s leading learned men – astrology, numerology, alchemy and the Kabbalah. Mathematics, Dee learned from these magi, was a unique international language that operated on several levels. Most obviously, mathematics was a practical subject, vital for navigation, surveying and building. But more subtly, mathematics provided the key for entering the sphere of magic.

Dee’s reputation as a magician overshadowed his more conventional achievements. When things went wrong, it was only too easy for his critics to accuse him of summoning up evil spirits. Dee’s career depended on who sat on the throne. When Mary was queen, he was condemned for using his magic skills to plot against her and was made a prisoner at Hampton Court. In contrast, he flourished under Elizabeth I, who admired Dee enormously. Elizabeth employed him to work out the most propitious day for her coronation, and once she was queen, appointed him her court astrologer.

Under Elizabeth’s protection, Dee’s influence spread and his wealth grew. He converted his large, rambling house at Mortlake (about ten miles west of London) into the unofficial equivalent of a private research institute. Conveniently situated on the Thames near the royal palaces at Richmond and Hampton Court, Dee’s home attracted many distinguished visitors. To support his scholarly studies, Dee built up England’s largest private library, which was so splendid that Elizabeth rode over on horseback to admire it. (Many of his 4,000 books and 700 rare manuscripts are now in the British Museum.) As well as buying books and manuscripts, Dee poured money into instruments and hired assistants to help him in his research.

His tasks included reforming the calendar and giving navigational advice about voyages of exploration; he also became involved in some tricky political issues, such as deciding the legal basis for claiming Greenland and North America. Wealthy gentlemen paid Dee to calculate their astrological horoscopes, and he published learned Latin treatises on mathematics and astronomy. For practical tradesmen, he wrote in English, providing important instruction books on mathematics, navigation and geography. Dee’s skilled knowledge of navigation made him a valuable asset as England expanded her overseas trade. He had good connections at court and was well regarded in aristocratic circles. His future seemed secure.

By his mid-fifties, Dee was England’s most famous scholar, but he was dissatisfied. ‘All my life time I had spent in learning,’ he moaned. ‘And I found (at length) that neither any man living, nor any Book I could yet meet withal, was able to teach me those truths I desired, and longed for.’ Dee aspired not only to learn more about the world, but also to understand God. He prayed for help, and in 1581 he established contact with God’s angels. To make his records of these spiritual communications more reliable, he decided to operate through a medium. After rejecting some obvious frauds, he found the perfect intermediary, a man called Edward Kelly who claimed to have special powers of communication. At frequent intervals over the next eight years, Kelly gazed intently into a crystal globe and reported hearing hundreds of angelic pronouncements. Totally confident of Kelly’s authenticity, Dee faithfully recorded their conversations – he had successfully communicated with spirit beings from another plane of existence.3

After Kelly and the angels moved in, life in the Mortlake household was no longer the same. Long days were devoted to transcribing declarations from Raphael, Uriel and other holy messengers. Dee persevered, convinced that he was truly gaining access to the beneficial knowledge that he sought. However, the angels became less cooperative, perhaps because Kelly was worried about being arrested for an earlier crime. As tensions escalated, Dee was rescued by one of his many admiring visitors, a wealthy Polish nobleman, who invited the combined Dee and Kelly families to visit him in Poland. Unfortunately, the funding that he provided for their alchemical research soon ran out, and they were forced to go on the road displaying their skills.

Sick, old and short of money, Dee eventually became disillusioned by Kelly’s underhand activities and abandoned him in Prague. He returned to England, where Elizabeth protected him while she was still alive. Dee eventually died at Mortlake in 1608, by then so poor that he resorted to selling off his library books for food.

Angels and magic, navigation and astrology, success and disillusion: a sad and romantic story, but surely nothing to do with science? The answer depends on what sort of history you want to tell. One route into the foreign country of the past runs along well-known roads, singling out famous scholars like Isaac Newton or Robert Boyle who led comfortable lives, moved in prestigious academic circles and published books that seem to be direct precursors of modern science. But other tracks exist as well, which lead to men who are less well-known and who were involved in activities not now regarded as scientific. Dee railed against the smear campaign launched by his enemies. Why, he demanded, should I, an ‘honest Student, and Modest Christian Philosopher’, be vilified ‘as a Companion of the Helhoundes, a Caller, and Conjurer of wicked and damned Spirites?’ He made this bitter complaint in a learned disquisition on the mathematical sciences – hardly the publication one would expect from a wizardly magician. Modern historians have rewritten Dee’s story to include him within the history of modern science.4

Dee was an expert on navigation, and the practical mathematical information in his books was just as important for later sciences (such as geomagnetism and meteorology) as the theoretical debates of scholarly, sedentary natural philosophers. And the complicated astrological calculations he carried out for his clients were far closer to mathematical astronomy than to a newspaper columnist’s glib horoscope. At the time, astrology and certain kinds of magic were highly respected. It is unfair of us to sneer at them because they stemmed from a view of the universe that has now been rejected.

Although their activities were often misinterpreted, men like Dee called themselves natural magicians because they wanted to make it clear that they were not dealing in black magic, which was the art of communicating with supernatural demons and witches. Instead, they operated by tapping in to astral influences and they set themselves the highest aspirations – wisdom, virtue, closeness to God. According to their model of the universe, the spiritual and the material realms were intimately bonded together, so it made sense to seek guidance from angels. Especially in continental Europe, magic and the occult were legitimate topics to study, although there was a wide range of different approaches. With centuries of scholarship behind them, Renaissance magi constantly experimented to test how different substances and techniques could help them achieve the effects they sought. Not so differently from modern scientists, they were trying to harness nature’s hidden powers.

Dee has been vilified as an evil magician, yet he was Elizabethan England’s most eminent mathematical astrologer whose interest in spirits was shared by leading scholars. Even Newton gained many of his insights from poring over alchemical treatises which – like the books Dee studied and wrote – portrayed a harmonious, interconnected universe. Dee published important texts on mathematics, navigation, geography, subjects that directly influenced the new theories and instruments developed in the early Royal Society. As Sprat’s frontispiece (see Figure 8) implies, Fellows of the Royal Society later adapted practical implements of the type described by Dee and relabelled them as instruments of natural philosophy. Similarly, although alchemy and astrology have now been discredited, chemists and astronomers built on their traditional techniques that had been developed over centuries.

In addition to this intellectual significance, there are other reasons for reinstating Dee in science’s history. For one thing, unlike many of his contemporaries, he was a natural philosopher who carried out experiments as well as reading books. Furthermore, examining the origins of modern science means knowing not only what people were studying, but where they were doing it. Dee is important because he worked at home rather than in a monastery or a university.

Four hundred years ago, in Dee’s lifetime, there were no university courses on science, no large research laboratories, not even any scientific societies or institutions. In a sense, men like Dee were engaged in two types of experimental programme. Most obviously, they were using their new instruments to explore the natural world instead of relying on the authority of ancient texts such as Aristotle and the Bible. But in retrospect, we can see that they were also embarked on a second kind of experiment. By using their own homes as the place to pursue their investigations and earn some money, they were trying out a new style of living. Searching for scientific knowledge involved changing traditional social patterns. Understanding how science started entails examining how families coped with the demands of natural philosophy as the structure of society altered.

By the middle of the seventeenth century, there were several scientific partnerships in private houses, such as Robert Boyle and his sister Katherine Jones, John Evelyn and his wife Mary Browne, and Robert Hooke and his niece Grace Hooke.5 One way of thinking about these scientific households is to regard them as social experiments, attempts to forge a new type of small community. These trials in living had momentous outcomes. In some respects they failed, because by the end of the nineteenth century most scientific research was taking place outside private settings. Although some scientists – including Charles Darwin – were still carrying out research in their own family homes, men (and by then, a few women) had generally moved out to work in universities, industrial laboratories and scientific academies. But in the long term, these experiments were hugely successful, because natural philosophers flourished and found ways of making their investigations financially profitable. Initiatives like Dee’s provided the foundations of our modern technological society, in which professional science and financial interests are bonded together.

Inevitably, when science was happening at home, women were involved. Compared with women like Katherine Jones, Mary Browne and Grace Hooke, Jane Dee does not seem herself to have been involved in experimental research. Like many other wives, her existence is generally ignored. Yet John Dee’s livelihood, the new type of scientific career he was forging, depended on her cooperation. The integration of science within society, and the upheavals in domestic life that this entailed, only became possible because of these silent partners. So another way of telling John Dee’s story is to place more emphasis on his wife Jane.

But first, a comment on names. One way of restoring forgotten women is to dignify them with their own surname instead of their husband’s. All very well and politically correct, but there are objections to this strategy. For one thing, it is more historically sensitive to describe people as they and their contemporaries knew them, and this almost inevitably means referring to wives by their married name. However objectionable it may be to modern feminists, these women did derive part of their identity – psychologically as well as legally – from being married to a particular man. Reverting to their maiden name (which in any case, a woman inherited from another man, her father) would conceal a status that was important to them. There is also a practical problem of communication: does it really make sense to confuse readers by referring to Mary Godwin rather than Mary Shelley, or to Marie Sklowodska rather than Marie Curie? There are no easy answers to these problems. However, what does seem vital is to treat men and women symmetrically, and not condescendingly use first names only for women. So, at the risk of being cumbersome, in this book wives and husbands are generally called by both their names.

Virtually none of Jane Dee’s own words survive, but her experiences can be partially reconstructed by interpreting existing documents in new ways.

Jane Dee (née Fromond) (1555–1605) deeply resented Kelly and the angels. No doubt she often pointed out that Kelly had appeared bearing a false name but minus his ears, which had been cut off as a punishment for forgery. A couple of months after Kelly arrived, John Dee made a note (later scored through) that his wife was ‘in a marvellous rage at 8 of the clock at night till 11½ and all that night and next morning till 8 of the clock, melancholic and choleric terribly’.6 Ironically, it is only because of John Dee’s faith in the angelic exchanges mediated through Kelly that so much information about her feelings and activities survives. For thirty years, John Dee kept an intimate diary, in which he aimed to explore systematically how changes in the heavens affect life on Earth. Intermingled with dictated diagrams and speeches received through Kelly are details of births and journeys, illnesses and debts, visitors and quarrels – unique evidence about the daily life of a philosophical wife.

5 February 1578: ‘My marriage to Jane Fromonds’. A terse diary entry. Other comments hint at hidden resentments on both sides. When he became a father for the first time on his fifty-second birthday, John Dee recorded the astrological conditions of the conception and the birth. Similarly, in the interests of research, he observed her illnesses, meticulously noting any cramps or the colour of her vomit. According to him, she was often ‘testy and fretting’, impatient, or angry with the maids – but if only we could hear her side of the case, she could surely give reasons for her fits of temper. Many partnerships would have dissolved under such intense proximity, but Elizabethans took church marriage vows very seriously. Despite their rows, the couple stayed together until her death almost thirty years later, and their marriage generated a total of eight children (‘generated’ is a carefully chosen word: some of the babies died, and two of them were associated with a tumultuous period when the angels ordered John Dee and Kelly to swap wives).

Jane Dee, a gentleman’s daughter from the court of Elizabeth I, found herself in a strange position. Neither she nor her husband fitted into any existing category, and there were no established guidelines for how either of them should conduct themselves. They got married over eighty years before the foundation of the Royal Society, and no collective identity had yet been established for natural philosophers. Only later did this become a recognised term embracing a large variety of men who used experiments and instruments to study nature, often with the overarching goal of learning more about God. Moreover, at this time, most scholars were single. In England, many of them were secluded in monasteries or universities, neither of which allowed their inhabitants to marry. In contrast, European magi did have private accommodation, but they avoided marriage in order to keep their souls pure. John Dee broke away from all these conventions by living at home, marrying and trying to support his family from his scientific work. Both Jane and John Dee were involved in forging this new type of married existence, which later became very common amongst scientific researchers.

Jane Dee was torn between conflicting codes of behaviour. As a virtuous wife, she should submit to her husband’s wishes, especially as he was nearly thirty years older than her. For women, marriage often meant being transferred from a father’s authority to a husband’s. On the other hand, gentlemen were usually occupied at court or in outdoor activities, leaving their wives in charge of the household (Figure 19). Jane and John Dee were forced to negotiate the ground rules for a new kind of domestic experimental partnership, one that would become increasingly common during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

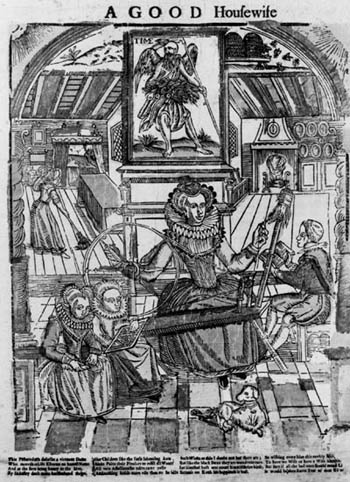

Elizabethan men prescribed separate roles for themselves and their wives: ‘Whatsoever is done without the house,’ intoned a guidebook to marriage (written by a man), ‘that belongs to the man, and the woman [is] to study for things within to be done.’ Confined at home while their husbands went out to work, women were forced into economic dependency, yet did exert authority inside their houses. Figure 19 shows a virtuous housewife who, resembling a less privileged version of Elizabeth I, is reigning over her domestic realm. The dog at her feet symbolises marital fidelity, while Father Time is preparing to crown her with a laurel wreath as a reward for good behaviour.7

As in many similar pictures and pronouncements, there is a certain amount of wishful thinking going on. Apprehensive about their women’s strength, Elizabethan men proclaimed their own power. The verses here include a facetious couplet pointing to women’s inherent Eve-like nature:

Fig. 19 An idealised Elizabethan housewife. A good housewife, c. 1600, hand-coloured woodcut, c. 1750.

Such Wives as this I doubt not but there are;

But like the black Swan they are wondrous rare.

This picture illustrates an idealised version of Elizabethan domesticity. Powerfully placed at the centre of her tidy, well-organised house, the woman is spinning wool, the cliché for feminine work. But she was also responsible for superintending the servants – hence the girl sweeping in the background – and for minding her children, here neatly divided into the appropriate gender skills: embroidery for the two girls, and book learning for the boy. Women also took charge of the family’s health, and exchanged recipes for medicines and tonics. When a baby was born, a network of women rallied protectively round the new mother for several weeks, creating a nurturing female environment from which men were excluded.8

Even Elizabeth I had been taught to cook and sew as a girl, but when she reached the throne she devised strategies for operating as a woman in a male world. Jane Dee, an exile from Elizabeth’s court, had to find her own ways of resolving the conflicts between ruling over her household and accommodating her husband’s research activities. The lines of authority were blurred. Inside their home, who was responsible for the experimental workers: the wife or the husband? Who was meant to cope when, as happened on several occasions, John Dee’s servant George fell off his ladder? The children were another source of contention. Unlike other Elizabethan gentlemen, John Dee was no absent father figure, but should he be involved in looking after them? He struggled to reconcile being the sole breadwinner with staying at home to work instead of going out. He must often have wondered whether he should choose a more orthodox, reliable way of supporting his family, one that would not involve constant worries about money and security. No wonder that Jane Dee scared her husband by flying into ‘mervaylous rages’. She was encountering problems that became more and more frequent as entrepreneurial philosophers converted their houses into schools, workshops and research centres.

* * *

As well as managing the domestic staff – eight of them at one stage – Jane Dee had to look after her husband’s live-in assistants and apprentices, supervising their food, health and accommodation. She must have been relieved that some of them experimented in the outhouses, which had been converted into alchemical workshops. However, Kelly was based in John Dee’s study, right in the middle of the house, as though he were an invader into her territory. Like Kelly, some of these assistants had dubious pasts, and John Dee deliberately picked moody men whose melancholic temperaments would make them more sensitive to astral influences. Sometimes they were accused of crimes, and magistrates visited the house to take them into custody. The domestic servants could also be troublesome: a couple of maids twice set their room on fire, and the children’s nurse explained away her erratic behaviour by claiming that she had been tempted by an evil spirit. Jane Dee found it difficult to discipline such a mixed household, and sometimes took out her rage on her own children – once she hit her eight-year-old daughter so hard that her face bled.

Money was a major issue. Sometimes Jane Dee pulled strings by going back to the court and pleading for help from Elizabeth I. The couple often settled wages and paid bills in arrears. John Dee had no regular income, yet Kelly threatened to leave without frequent salary rises, while the servants, staff and wet nurses were further steady drains on the family economy. John Dee kept buying expensive books and equipment and insisted that his wife lay on generous hospitality for the stream of important visitors. Jane Dee was in a Catch-22 situation: she had to convince potential patrons that her husband deserved sponsorship, yet at the same time conceal her limited budget by demonstrating that together she and her husband ran a flourishing, efficient household.

One time, in desperation, she overcame her loathing of Kelly to remind the angels (through him) of their poverty. Surely, she asked, she should not have to pawn their possessions in order to finance philosophical experiments? Kelly summoned up a handsome young man in a white coronet, who tartly reminded her to be faithful and obedient, and recommended that she go back to her sweeping. ‘Give ear unto me, thou woman,’ the spirit ordered her through Kelly, ‘is it not written that women come not into the synagogue?’9 The synagogue? Kelly and John Dee carried out their experiments behind double closed doors, making the study an inner sanctum reserved for men; even the outbuildings were the preserve of a gloomy assistant who operated the alchemical stills. Instead of ruling over her own house like other Elizabethan women, Jane Dee was being squeezed into restricted quarters. She had to organise her rooms not only to make domestic operations run smoothly, but also to give John Dee and Kelly privacy for their conversations with the angels.

Life must have been exceptionally chaotic when the entire household – around twenty assorted Dees, Kellys, children, servants and assistants – trailed round central Europe. Even at Mortlake, it had been hard to coordinate conflicting schedules and make John Dee’s experimental investigations fit in with the other family activities. During one exceptionally long session with the archangel Michael, John Dee ‘axed if I should not cease now, by reason of the folk tarrying for supper’. The scene is easy to envisage: hungry children, an angry wife, the food drying out . . . how many other wives have been left to entertain the children while their husbands finished off an experiment? But Kelly was adamant. Speaking through him, Michael instructed John Dee to ‘lay away the world, continue your work’ – the meal had to wait.10 Like the Good housewife of Figure 19, Jane Dee was trying to impose regularity in her own household, yet her routine domestic timetables were being overthrown by the demands of research.

Sex was another source of conflict. As a Renaissance magus, John Dee should have kept himself pure by abstaining, especially if he wanted to establish clear lines of communication with the angels. Sometimes he noted that she had initiated sex; was this perhaps to absolve himself from the responsibility of tainting his scholarly soul? On the other hand, Jane Dee knew that her obligation as an Elizabethan wife was to bear him many children and so help atone for Eve’s original sin by suffering the agonies of childbirth. But she was also required to be obedient to her husband, and sometimes his desires conflicted with her duty – especially when the angels, communicating their instructions via Kelly, insisted that John Dee and Kelly exchange wives. (One interpretation of this unusual order is that Kelly was desperate for children, but his wife was infertile.) Jane Dee was horrified. In a stormy session, she ‘fell a weeping and trembling’, her husband recorded, but ‘I pacified her as well as I could’. John Dee apparently did try to talk the angels out of the plan, but eventually resorted to persuading his wife that the virtuous path lay in accepting God’s command. Reluctantly she accepted, although she did insist that they all four share the same room so that her husband would be nearby.11

Jane Dee coped with the incompatibility of marital obedience and fidelity by praying ‘that God will turn me into a stone before he would suffer me, in my obedience, to receive any shame’. Her husband resolved the conflicts between natural philosophy and Elizabethan conventions by converting Jane Dee into the object of his astrological research. By recording her body’s behaviour, he could study her fertility and collect data for improving his horoscope techniques. He systematically recorded her periods, moods and illnesses; to indicate when they had intercourse, he devised a special symbol to represent the combination of Venus and Mars. Natural philosophers often experimented upon themselves, and many others must also have kept intimate diaries about their wives, trying to impose orderly patterns on female bodies (the relationships between menstruation, fertility and conception were unresolved at this time). Charles Darwin’s sons, for instance, kept a register of their own sexual experiences because they were interested in exploring eugenic methods of ‘improving’ the population.

When the wife-swapping agreement with Kelly came into effect, John Dee coolly noted the event in rhyming Latin: Pactum factum (the agreement has been carried out). But someone (Jane Dee, perhaps?) has cut out the rest of that page in his diary. Nine months later, John Dee recorded that ‘Theodorus Trebonianus Dee was born, with [Mercury] ascending in his horoscope.’ Although Theodore was presumably Kelly’s child, John Dee claimed paternity, perhaps because he felt that this youngest son represented the culminating achievement of the angelic seances.12

Soon after Kelly arrived at Mortlake, he dreamed – or was it the angels speaking to him? – that Jane Dee was killed when she fell over a gallery rail. Despite this evidence of Kelly’s hostility, she survived for more than twenty years, dying in Manchester a few years before her much older husband, probably from the plague. Several of her children may well have died with her, although this can only be inferred from the absence of their names in John Dee’s diary. He did, however, record the death of the angelically conceived Theodore at the age of thirteen.

* * *

Even by Elizabethan standards, Jane Dee’s life was extraordinary. Few wives had to tolerate a host of angels who excluded her from parts of her own home, dominated meal times and forced her into her rival’s bed. Yet instead of focusing on these exotic incidents, it is more rewarding to think about other aspects of the Dee ménage. John Dee’s diary shows his voyeuristic control over his wife’s body, yet it also reveals the daily experiences that would become increasingly common during the following two centuries, as scientific research moved inside women’s own homes.

John Dee’s interests seem bizarre to us because we have rejected Renaissance visions of a universe bound together with occult virtues. Many learned Elizabethans accepted the value of astrology and alchemy, but such knowledge became excluded from legitimate science. From our perspective, John Dee seems to be a late representative of vanished systems of belief. However, he could also be seen as a social pioneer, an entrepreneur who strove to integrate his philosophical activities with his domestic life. Viewed in that way, John Dee appears as an early example of the natural philosophers who helped to make science into a collaborative, public enterprise.

Renaissance scholars worked in private studies and only a select group of privileged men had access to their arcane knowledge. In contrast, modern scientists receive large sums of money to carry out research and publicise their results. Taking experimental philosophy into the public arena was a key move in this transformation. In the early eighteenth century, Mr Spectator – the essayist Joseph Addison – wrote that ‘I shall be ambitious to have it said of me, that I have brought Philosophy out of Closets and Libraries, Schools and Colleges, to dwell in Clubs and Assemblies, at Tea-Tables, and in Coffee-Houses.’13 He was continuing an initiative that had been launched more than a hundred years earlier by John Dee and his contemporaries.

Bringing experimental research into private homes meant that women became involved. Details about Jane Dee’s life have survived because her husband kept an unusually detailed diary, but many of her experiences illustrate the difficulties that other women must have encountered. Scientific wives often had to look after residential assistants and students, providing their food and coping with their misdemeanours. How many of them were, like Jane Dee, left to placate the children and keep the dinner warm while their husbands finished off a piece of work? How many of them watched the family finances being poured into new instruments, books and chemical supplies? How many of them, as Benjamin Franklin wrote, ‘threatend more than once to burn all my Books and Rattling-Traps (as she calls my Instruments) if I do not make some profitable Use of Them’?14

Every woman’s life is unique, and it is hardly likely that many families were governed by directions from angels. However, during the following three centuries, other wives, sisters and daughters invented their own ways of reconciling the conflicting demands of domestic duties and scientific investigations. If they had not done so, science as we know it would not exist and the technological world we live in would be very different.