No one has more intelligence, aptitude, and talent for all kinds of work . . . She [Madame Lavoisier] has a masculine soul in the body of a woman.

Pierre Du Pont de Nemours, letter to Philippe Harmand, 1801

When Judy Chicago laid the table for her imaginary dinner party, she brought together guests from many cultures. But no essential quality of womanhood could have united these visitors. Even scientific women from the same period had very different experiences. Consider Marie Anne Pierrette Paulze Lavoisier and Caroline Herschel, who lived at almost the same time but had only one major characteristic in common. From their childhoods, the lives of both women revolved around one single man. Herschel dedicated herself to her brother, and Paulze Lavoisier to her husband, the famous French chemist Antoine Laurent Lavoisier. There the similarities between these two women end.

To start with, they were born into very different family circumstances and displayed different personalities. Herschel’s life was characterised by poverty and self-sacrifice, and she focused her attention inwards, towards the psychological and physical demands of her brother. Scientific gossip or local news did occasionally intrude into her family memoirs, but generally she insulated herself from world events. In comparison, Paulze Lavoisier was rich and outward-looking, deeply committed to social reform, and her fate was governed by the French Revolution. In addition, there were strong contrasts between French and English science. England’s prominence relied on private enterprise and individual initiative – the Herschels’ small royal salaries were unusual. But in France, both before and after the Revolution, the state supported scientific research financially. As a consequence, science developed differently in the two countries.

Caroline Herschel subsumed her existence beneath her brother’s, but Antoine Lavoisier’s wife did make a partial declaration of independence. Paulze was her maiden name, and even after she was married, she signed her published chemical drawings and business correspondence Paulze Lavoisier. In recognition of this semi-bid for a separate identity, that will be her name for this chapter.

Paulze Lavoisier (1758–1836) and her husband moved in the same radical circles in Paris as the artist Jacques-Louis David, who painted several of the huge canvases now hanging in the Louvre. Although history paintings of classical scenes later became unfashionable, during the Enlightenment they were regarded as the pinnacle of artistic achievement. By depicting well-known events or myths from the past, they provided object lessons in ethics and taught viewers how to make moral decisions. David proclaimed his revolutionary allegiance by painting huge canvases of Roman scenes that were imbued with modern political significance.

David was also a brilliant portrait artist, and he yielded to the persuasion of Paulze Lavoisier, who was one of his students, to paint her with her husband (Figure 24). This stunning work dominates the gallery where it is on display in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. The picture’s sheer size – around nine feet by seven – is immediately overwhelming, to say nothing of its shimmering light and colour. The vibrating reflections from the glass vessels, the luminous white cambric of her dress and the polished metal of his shoe buckles all set off the rich glow of the red velvet tablecloth. Even Lavoisier’s dark suit has a lustrous texture, accentuated by his white cuffs and jabot, which sparkle like the experimental flasks.1

Despite this picture’s radical credentials, it became a victim of revolutionary activity. As a wealthy landowner and tax collector, Lavoisier was inevitably a target of suspicion, and his financial activities ultimately led him to the guillotine during the Reign of Terror. He was also in charge of gunpowder production, and in 1789, three weeks after the storming of the Bastille, a riot erupted when Parisians accused him of shipping powder out of the city to prevent the people from using it. David’s picture, completed the previous year and overflowing with optimism for future reform, was diplomatically removed from display and replaced by a less contentious couple whom he also painted, the mythological Greek lovers Helen and Paris.

Fig. 24 Marie Paulze and her husband Antoine Lavoisier. Jacques-Louis David, 1788.

David intended this double portrait, like his history paintings, to tell several stories . . .

Most obviously, this picture is about success. When he commissioned this intimate scene of a fashionable Parisian couple, Lavoisier had paid David almost five times a professor’s annual salary, and the artist produced an appropriately sumptuous and exquisitely painted canvas. Wealthy by birth as well as through marriage, Lavoisier funded his comfortable life from his financial activities as a state tax collector. But his major interest was chemistry, and he is often said to have initiated a chemical revolution that overturned science as dramatically as the political Revolution in which he died. Painted in 1788, the year before the Revolution broke out, David’s picture is a dazzling display of bourgeois accomplishment.

Lavoisier’s elegant extended leg divides the scene diagonally, so that Paulze Lavoisier’s dominating central presence is balanced by her husband’s chemical equipment and papers, which are all on the right-hand side. The apparatus carefully arranged on the table refers to Lavoisier’s major achievement, the identification of oxygen. As well as being scientifically important, this discovery carried great national significance, because it symbolised how Lavoisier had overthrown the older system of his English rival, Joseph Priestley. At his feet, the large glass balloon nestling in its plaited horsehair collar was used for collecting and weighing air. Starting at the bottom right, the instruments have been ordered chronologically to represent the major stages in Lavoisier’s career.

Goose quill in his hand, Lavoisier is correcting the proofs of a book, probably his Elements of Chemistry, which came out the following year. This was his most important book, in which he persuasively laid out his revolutionary agenda to found a new chemistry. Taking his cue from algebra, Lavoisier introduced a systematic chemical language – essentially the names and symbols still in use today. Applying his financial acumen, he insisted on a balance-sheet approach, expressing reactions as equations and meticulously checking that weights and volumes always added up. Lavoisier’s new chemistry depended on precise measurements, for which he designed accurate instruments: hence their prominence in this portrait.

David and the Lavoisiers both moved in the same progressive groups, and here the politically sensitive artist is advertising the radical chemist’s forward-looking ideas. Even the portrait’s colours seem revolutionary. Lavoisier wears Third Estate black, and the canvas is dominated by red and white, laced with the suitably feminised blue of Paulze Lavoisier’s sash. And although it shows an elite couple, the workers have not been forgotten: by painting the experimental instruments with the loving attention of a Dutch still-life master, David celebrates not only Lavoisier’s ingenuity in conceiving them, but also the skill of the artisans whom he employed to execute them so beautifully.

David is pledging his conviction that future improvement lies in scientific research, a controversial commitment that still needed to be openly declared. Lavoisier boasted about revolutionising chemistry, and he was also an active social reformer. He instigated many administrative changes that made local government more democratic, and he used his scientific expertise to improve people’s lives – by renovating Paris’s decrepit drainage system, overhauling the dilapidated prisons and hospitals, rationalising the old-fashioned system of weights and measures into the metric system. He also wanted to revolutionise France’s agriculture and remedy the chronic food shortages. From his laboratory research, Lavoisier argued that physical labourers required more to eat than sedentary workers, and at his model farm in the country, he analysed his planting experiments with an economist’s precision, keeping accounts of the human energy expended as well as the crop yields and selling prices.

David and his colleagues were trying to revitalise the French arts. They turned to antiquity for inspiration, yet at the same time contrasted the old and the new; three classical pilasters dominate the bare back wall of this innovatory study-cum-laboratory. For this modern double portrait, David chose a very similar pose to his treatment of Helen and Paris, another devoted pair. In both pictures, the man looks adoringly up towards his female partner as though they were destined for one another. But whereas Helen submissively returns Paris’s captivating gaze, Paulze Lavoisier stares confidently out at the spectator. As foundations for a better society, David was prescribing not only science but also new concepts of love and liberty.

Or was he? David has bequeathed an ambiguous version of Paulze Lavoisier. Lavoisier seems to be beseeching her for guidance, and yet, draped decoratively on his shoulder, she could well be a devoted yet ordinary wife totally ignorant of chemistry. Her deceptively natural coiffure à l’anglaise, a powdered blonde wig concealing her own dark hair, suggests long hours dedicated to her appearance. In her simple white dress, the traditional colour symbolising female purity, Paulze Lavoisier might personify female nature. It is hard to tell whether Lavoisier is awestruck by his wife’s aura or by the subject he studies. On the other hand, she appears distracted, even irritated. Has she been interrupted in the course of advising her husband about a detail in his proofs? Is she the driving energy behind his fame, or is she merely a figurehead, a muse who provides a source of inspiration with no real knowledge or skills of her own? One of Paulze Lavoisier’s friends wrote a verse for her that neatly summarises some of the painting’s ambivalence:

For Lavoisier, subject to your laws

You fill the double role

Of muse and secretary.2

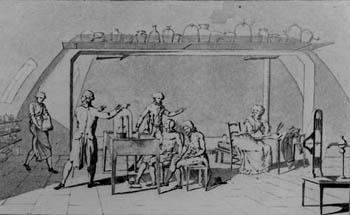

Still further stories lie concealed within this picture. Separated from the zone of scientific activity by Lavoisier’s outstretched leg, Paulze Lavoisier’s domain covers the left-hand half of the portrait. On the armchair in the back corner is a large folder, David’s tribute to her activities as his pupil. Inside this portfolio could be hidden some of her own pictures – the experimental sketches that document her participation in the research carried out in their own private laboratory at home (Figure 25), and the diagrams she drew for Lavoisier’s Elements of Chemistry (Figure 26). Paulze Lavoisier left behind firm evidence of the active part she played in building her husband’s career.

Marie Paulze was only thirteen when she rejected her first suitor – a man of fifty – and instead agreed to marry Lavoisier. This ambitious young lawyer, twenty-eight years old, was one of her father’s business colleagues. Fresh out of a convent, and with only a scanty education, she found herself in charge of a Parisian household, and the wife of a wealthy financier who was obsessed by chemistry and geology. Lavoisier followed a rigorous schedule: science from six to nine in the mornings, a full day of business meetings, then back into the laboratory for three hours after dinner. If she wanted to spend time with him, she had to work. Despite her youth, Paulze Lavoisier immediately embarked on intensive courses of self-instruction so that she could share her husband’s activities. For more than twenty years they worked and travelled together.

An English girl in her situation would have found herself automatically excluded from male intellectual circles, and might have idled away her time at parties or devoted herself to her children. But because she lived in Paris, Paulze Lavoisier could enter mixed conversational groups, which were often presided over by women. Although – like Émilie du Châtelet – she could not attend meetings at the Academy of Sciences, she soon found out what had happened there because Lavoisier brought his friends back to tea with her afterwards. Women, according to French Enlightenment ideology, were civilising agents whose intrinsic docility was valuable because it moderated male aggression. Their function was to eliminate brutality and oppression, and so help create a polite, intellectual nation. The eminent naturalist Georges Buffon argued: ‘It is only among the nations civilised to the point of politeness that women have obtained that equality of condition, which however is so natural and so necessary to the gentleness of society.’3

Women and men were different yet complementary – a condescending view by modern standards, but at least it gave women a central role. By placing Paulze Lavoisier in the centre foreground, close to her husband, David has painted an idealised picture of civilised collaboration. The pile of papers on the table is a product of their joint labour, the book to which they had both made their own individual contributions. Like Lavoisier’s own molecular model of chemical affinities, the couple have reached an equilibrium by balancing their opposing characteristics. They form a stable pair, the foundational unit recommended by Jean-Jacques Rousseau for a good society.4

At this time, before science had become professionalised, there were no established codes of behaviour for either men or women who were involved in experimental research. Many scientific couples worked together, enjoying marriages that seem to have gained their strength from intellectual companionship rather than from domesticity and parenthood. Like Paulze Lavoisier, the wives of eminent men at the Academy of Sciences often translated foreign scientific books; others wrote novels, plays, political tracts. Several French women of this period were responsible for introducing foreign texts into France. Marie d’Arconville commented on and translated a major English chemistry text, and Françoise Biot’s translation of a German physics book went through four editions. Paulze Lavoisier’s friend Claudine Picardet, who also ran an important scientific salon, could cope with German, Swedish, Italian and English.5

Typically in these couples, the husband was far older, they had relatively small families and both partners engaged in romantic affairs. Paulze Lavoisier and her husband fitted this pattern: they had no children, and Paulze Lavoisier took the opportunity of his frequent absences to become deeply involved with one of his close friends, Pierre Du Pont de Nemours. This was no passing intimacy. They were almost certainly lovers from 1781, and when she rejected his proposal of marriage after Lavoisier’s execution, he told his son that ‘she had all my heart and she has broken it’. He remained faithful, reminding her much later of ‘the inviolable and tender affection that I had vowed to you for thirty-four years’.6

French men’s lives depended on patronage. By marrying the daughter of a senior colleague, Lavoisier had promoted his legal career and improved his financial situation. Similarly, when the wealthy banker and politician Jacques Necker was entertaining a young relative from Geneva, Albertine de Saussure, Lavoisier consolidated his own position by inviting her round to his laboratory. The daughter of a famous geologist, she had started recording her scientific observations when she was ten years old, and her face was scarred by some early chemical research that had gone wrong. She sent her father excited letters detailing the chemical experiments that Lavoisier had performed especially for her. Later, married to a botanist, de Saussure ran her own salon, the scientific counterpart to the literary circle clustered round her cousin, Germaine de Staël.7 As Lavoisier gained prestige, he started to adopt his own younger protégés – when a junior chemistry teacher wanted to repay Lavoisier for his help, he gave private lessons to Paulze Lavoisier.

The key place for men to meet useful contacts and solicit support was in a woman’s salon. Like other powerful French wives, Paulze Lavoisier ran a weekly salon where men and women met together to discuss the latest gossip, plays and scientific experiments. At her father’s house, Paulze Lavoisier had learned how to act as hostess after her mother had died, and so she could rapidly take over this vital role. Within a few years she was leading one of Paris’s most important scientific conversation circles, entertaining Benjamin Franklin, Joseph Priestley, James Watt and many other distinguished visitors. Lavoisier’s scientific success depended on being able to gain the backing of influential people by inviting them to these successful salons, which displayed the intellectual wealth he could gather around him.

Paulze Lavoisier was no mere table decoration – ensuring that these discussion evenings went smoothly was essential for maintaining her husband’s position. An American visitor who arrived to negotiate a price with Lavoisier for his Virginia tobacco was surprised that a woman should be more interested in intellectual matters than in the latest fashions. ‘She is tolerably handsome,’ he remarked, ‘but from her Manner it would seem that she thinks her forte is the Understanding rather than the Person.’ Nevertheless, he went to the ballet with her, invited himself to tea when Lavoisier was out, and went along with Franklin to one of her evening salons.8 Franklin recognised how powerfully these scientific wives were cementing together a new intellectual community. ‘In your company,’ he remarked to one salon hostess, ‘we are not only pleased with you but better pleased with one another and with ourselves.’ The salons were effectively power bases where wives could arrange patronage for their husbands. They also acted as mother figures for younger men, and Paulze Lavoisier took an active, informed interest in the research of Lavoisier’s assistants.9

For Paulze Lavoisier, an enlightened French wife, being Lavoisier’s humble assistant would not have been enough. Instead, she regarded their union as a complementary partnership, one to which she could bring essential skills that he lacked. Even as a teenage bride, Paulze Lavoisier immediately identified one of Lavoisier’s limitations – some of Europe’s most important chemical research was being carried out in Britain, but he could not speak English. As soon as they were married, she started to learn English so that she could translate books and papers into French for him. She also engaged a Latin teacher, and begged her older brother to help her ‘decline and conjugate for my own pleasure and to make me worthy of my husband’.10

Drawing was another talent that Paulze Lavoisier developed. She had lessons with David, who took on an unusually high number of female students. Franklin was delighted with the portrait of himself that she sent him, and she probably sketched other friends as well. More importantly for chemistry, she learned the professional drafting techniques that she needed to make accurate scale drawings of chemical apparatus – drawings that were vital for promoting Lavoisier’s revolutionary chemical ideas.

She asked Lavoisier to teach her chemistry, and they also arranged private tuition for her at home. Later, she went out to lecture courses at one of Paris’s private colleges. A fellow student sneered that ‘she was young, but not pretty. Somewhat pedantic, she had an excessively high opinion of herself.’ He accused her of stinginess, reporting that she walked home at night instead of taking a private carriage. Was she, perhaps, taking a secret detour to meet her lover, Du Pont de Nemours, before returning to her husband and his constant business meetings?11 In any case, she became very proficient at chemistry. When the English agricultural economist Arthur Young came to tea, he was impressed by her knowledge: ‘Madame Lavoisier, a lively, sensible, scientific lady, had prepared a dejeuné Anglois of tea and coffee; but her conversation on Mr Kirwan’s Essay on Phlogiston . . . and on other subjects, which a woman of understanding, who works with her husband in his laboratory, knows how to adorn, was the best repast.’12

Who works with her husband in his laboratory: this was no empty flattery, but a visitor’s report about real life in the Lavoisier household. Perhaps Young had been invited to attend one of Lavoisier’s Saturday sessions with his students, the high point of his week. Saturday was for him ‘a day of happiness’, wrote Paulze Lavoisier, when ‘a few enlightened friends, a few young people . . . gathered in the laboratory from the morning: it was there that we ate lunch, discussed, and created the theory that immortalised its author’.13 Paulze Lavoisier’s sepia drawings provide unique and invaluable information about Lavoisier’s laboratories and research techniques. Figure 25 shows Lavoisier and his team carrying out experiments on respiration. Only two such pictures survive, and they provide unique evidence of the particular instruments he used and the laboratories where he worked.

In the centre sits the subject, dressed in an impermeable suit of rubber-coated taffeta and pumping a foot treadle. So that the amount of oxygen he consumes can be accurately measured, he breathes from a flask through a tube that is held in his mouth with putty. Paulze Lavoisier is at her usual place by the small side table, recording the observations as the experimenters call them out – many pages in Lavoisier’s laboratory notebooks are in her handwriting. She was evidently a systematic, organised woman, since her other scientific tasks included filing the notes that Lavoisier scribbled on the backs of envelopes and playing cards. She has produced a Davidean portrait of a laboratory, in which the high shelf of flasks provides a stage-like setting for dramatic action. With his back to the spectator, Lavoisier theatrically directs operations, while Paulze Lavoisier is holding the same pose as David gave Lavoisier in their double portrait. By composing the picture as though she were an external spectator, she emphasises her status as a detached observer both inside and outside the laboratory.

Fig. 25 Marie Paulze working in the laboratory. Marie Paulze Lavoisier, ‘Experiments on the respiration of a man carrying out work’, probably 1790–1.

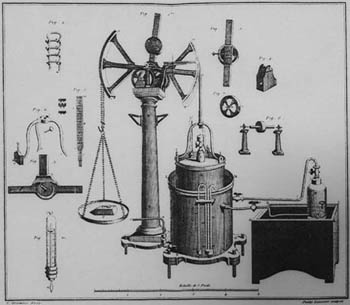

A century elapsed before these two sketches appeared in print, but thirteen of Paulze Lavoisier’s meticulously drawn plates were published in Lavoisier’s 1789 Elements of Chemistry (Figure 26). Precise instruments were central to Lavoisier’s chemical reforms, and Paulze Lavoisier’s illustrations made his pioneering text different in style and scope from previous ones. Instead of the rough impressionistic drawings that characterise older books, Paulze Lavoisier produced accurate scaled diagrams that would enable other chemists to build their own identical instruments and so reproduce Lavoisier’s results. As Young commented on the gasometer shown in Figure 26, ‘it is a splendid machine . . . too complex to describe without plates’. Paulze Lavoisier’s diagrams were a vital component of Lavoisier’s book, the propaganda piece for his new chemistry. She took great care over them. First she painted the instruments in watercolours, and then, using a pencil, she carefully copied these pictures on to squared grids that she had ruled out herself. After engraving her own copper plates, she supervised several proof stages, adding corrections until she was satisfied. Bonne (good) she finally wrote in approval, and signed the plates Paulze Lavoisier – the name she also used for business correspondence.14

Fig. 26 One of the thirteen plates by Marie Paulze in Lavoisier’s Elements of Chemistry.

Marie Paulze Lavoisier, 1789

By the time that Young arrived for tea, Paulze Lavoisier was corresponding with Europe’s leading chemists, attending their lectures and commenting on the latest scientific news. As Young remarked, she could converse so knowledgeably with him about Richard Kirwan’s An Essay on Phlogiston because she had translated it from English into French. She had worked on other British chemistry books and papers for Lavoisier’s personal benefit, but because her translation of Kirwan was published, it made a vital contribution to Lavoisier’s campaign of self-promotion. Kirwan, an Irish chemist, defended phlogiston, a theoretical substance that had been devised to interpret experiments on burning.

If Lavoisier wanted to revolutionise chemistry, it was essential for him to demolish the phlogistic views of Kirwan and his British allies. As part of their campaign, the couple even staged a theatrical mock-inquisition, in which Paulze Lavoisier played the part of a high priestess sacrificing phlogiston’s supporters on the altar of Lavoisier’s truth. For her French edition of the Kirwan book, she planned an elaborate allegorical frontispiece that would show the triumphant spirit of chemistry brandishing a flaming torch over the blindfolded, defeated figure of phlogiston. Although this was dropped, Paulze Lavoisier did provide the translation, the preface and some notes, while further criticisms were added by Lavoisier and his supporters.15

In any case, Paulze Lavoisier knew enough chemistry to pick holes in Kirwan’s work herself. In her French version of one of his articles, which was published in the prestigious Annales de Chimie, she added her own critical comments. Hiding behind the anonymity of a ‘Translator’s note’, Paulze Lavoisier formulated her denunciations – Kirwan’s forgotten to mention the water that was produced; the ammonia he used was obviously impure; he seems to have made a mistake here. In voicing such comments on Lavoisier’s behalf, she was, perhaps, transgressing the unwritten rules of French intellectual marriages, which were based not on equality, but on complementarity. He was the public man of reason; her role in their collaboration was to provide the skills that Lavoisier lacked – illustration, translation, formal entertainment, routine household and laboratory administration.

Twenty-three years of apparent stability and happiness: a long time, cut short only by Lavoisier’s arrest and execution. Like many relationships, theirs flourished because they spent time apart as well as together. In Paris, they worked with each other in their laboratory, and enjoyed entertaining their frequent guests as well as visiting other people. They were both deeply interested in music – Paulze Lavoisier probably played the piano – and went to the opera, ballet and art exhibitions. Yet Paulze Lavoisier also had long hours by herself to study, draw and see her lover Du Pont de Nemours. Three times a year, Lavoisier spent a few weeks at his model farm in the country, but Paulze Lavoisier was unenthusiastic about the conservative neighbours, and often found excuses for retreating back to Paris and Du Pont de Nemours. But she did not always stay behind. As Lavoisier threw himself into schemes for reforming chemistry, agriculture and government, Paulze Lavoisier travelled round France with him. Their itineraries were varied and intensive – a sugar refinery in Orléans, a chemical laboratory in Dijon (home of another chemical wife, Claudine Picardet), a glove factory in Vendôme . . . Lavoisier’s ideology of peaceful revolution involved hard work.

He was committed to improving the life of his peasant farmers, and he tried out new agricultural methods with the same precision as his laboratory experiments. Grain yields, milk production, craft supplies – everything increased under his methodical direction. Yet, as he constantly complained, the taxation system meant that he was earning virtually no income from the small fortune he poured into the land. The countryside was being starved, he protested, because the government provided no incentives for landowners to invest. Paulze Lavoisier shared his political idealism. At the farm, she kept production records and promoted local light industries to bring in money during the winter; together, the couple toured round factories in the hope of boosting the depressed economy. Paulze Lavoisier did her sums and made her recommendations. The profitability of a man-powered cotton mill was less than one using water power, she calculated; instead of spinning hemp, workers could earn more money by knitting Turkish hats – she suggested three a day selling at four sous each.

She also accompanied Lavoisier when he went to superintend another of his pet projects, a gunpowder factory where his reforms had more than doubled productivity in seven years. This was a sobering trip. During one round of experiments, another chemist and his sister were killed, and the Lavoisiers only escaped death because they had taken an hour off to have breakfast. They resolved to tighten the security precautions. ‘Only two minutes later,’ she wrote in shock, ‘and six of us would have been victims.’

When a reporter for the Journal de Paris described this fatal explosion, he remarked disparagingly that ‘discoveries of this sort are more harmful than advantageous to humanity’. Lavoisier and Paulze Lavoisier disagreed. They were both dedicated to achieving social reform through scientific research, and continued their heavy round of chemical experiments, agricultural innovations and factory visits.16

The accident had happened on 31 October 1788. Five years later, after a series of warnings as the Reign of Terror intensified, their lives changed far more abruptly.

4 frimaire An II: the Convention discusses tax collectors. By a show of hands, the revolutionaries agree ‘that those public bloodsuckers should be arrested and that, if their accounts are not presented within a month, then the Convention must hand them over to the sword of the law’.17 After a few days hiding with friends, Lavoisier gives himself up, and – accompanied by his father-in-law – joins the 200 inmates in the Port-Libre prison, where he remains for more than five months.

19 floréal An II: Lavoisier is searched, stripped of all his valuables, and brought before the Revolutionary Tribunal. That evening, hands tied behind his back, he stands behind his father-in-law in the place de la Révolution. Twenty-eight men are guillotined in thirty-five minutes – almost one a minute. ‘It took them only an instant to cut off that head,’ commented one of Lavoisier’s scientific colleagues, ‘but it is unlikely that a hundred years will suffice to reproduce a similar one.’18

The raw facts: undisputed, so straightforward to narrate. Motivations and allegiances remain less clear. Despite his radical ideals, Lavoisier was executed because his wealth made him a symbol of political oppression. Could he perhaps have saved himself? After all, many other wealthy men fled from Paris or bribed their way out of prison. And what was Paulze Lavoisier doing during the Reign of Terror? Surely she could have persuaded one of their influential friends to rescue him?

She visited Lavoisier regularly while he was in prison, liberally tipping her way round the warders to ensure that her husband and her father had enough food, clothes and firewood. She also helped Lavoisier to plan his defence, sending letters back and forth between the prisoners and their supporters on the outside. The furniture in their Paris flat was taken over by the revolutionaries, and thieves stole most of the livestock from their farm. They both knew that he was unlikely to survive. ‘My dear one,’ wrote Lavoisier, ‘you are . . . exhausting yourself both physically and emotionally, and, alas, I cannot share your burden.’ Be careful of your health, he continued; ‘my task is accomplished. But you, on the other hand, still have a long life ahead of you.’19

Both Paulze Lavoisier and Lavoisier seem to have spurned the possibilities of negotiating their way out of the situation. When a friend engineered an interview for her with Antoine Dupin, the official responsible for drawing up the charge sheet against Lavoisier, she stormed into his office, announcing that she refused to humble herself by begging for pity from a Jacobin. She sought justice not mercy, she declared: a noble attitude, but diplomacy or bribery might have been more appropriate.

Her life became still harsher after Lavoisier was guillotined. She wandered round the empty apartment. Furniture, instruments, ornaments – all gone, all confiscated. The only book remaining on the shelves was the catalogue of 560 vanished volumes, while the pale blocks on the panelling reminded her of the pictures that had disappeared. She knew that her own arrest was imminent, yet constantly put off taking refuge in the countryside with Du Pont de Nemours. Perhaps she was worried about becoming involved once again with a far older man. Or perhaps his attractiveness waned once he was available, no longer a forbidden fantasy. And there was also a financial complication: Du Pont de Nemours had borrowed money from Lavoisier to set up his printing plant, but was no longer able to keep up the debt repayments. Paulze Lavoisier procrastinated too long. On 22 messidor (10 July 1794) Du Pont de Nemours received a coded letter from his son: ‘Citizen Lavo,’ he learned, ‘has met with a very great tribulation . . . we hope that she will be happily extricated in a few days.’20 A few? She spent sixty-five days in prison, an ordeal she could have avoided by taking a less compromising attitude towards her accusers, as well as her friends.

Paulze Lavoisier was exonerated from suspicion of political activism by her scientific dedication. ‘It can be assumed,’ the surveillance committee reported, ‘that collaborating daily with her husband in his work, she was involved only with what related to their domestic occupations.’21 Paulze Lavoisier spent the next couple of years plotting retribution on Dupin and his allies. Du Pont de Nemours obligingly printed the brochure she wrote accusing Dupin of being a murderer, and he was eventually tried and demoted. Then she set about systematically searching for her confiscated possessions, pestering government departments for their return. Much of it came back – paintings, maps, furniture, even two bottles of mercury and twelve notebooks (six used, the inventory noted). After the farm and the Paris apartment were restored to her in April 1796, her financial security was assured.

As well as recovering her husband’s property, Paulze Lavoisier also wanted to rebuild his reputation. His former colleagues, worried about accusations of failing to protect him, were converting Lavoisier into a national hero. Modern chemistry was, they declared, a French creation, an enduring contribution to knowledge whose permanence was very different from the unseemly haste with which the former regime had removed his head. Lavoisier became doubly celebrated as a champion of experimental science and a martyr to Jacobin irrationality. A theatrical funeral ceremony attracted 3,000 visitors, but Paulze Lavoisier was not among them – she never forgave their friends for being unable (or unwilling?) to save her husband.

For her own tribute to his memory, she decided to publish his last manuscripts. While he was in prison, Lavoisier had been working on an edited collection of papers, but although Du Pont de Nemours started printing these Memoirs of Chemistry, he never completed the job, so Paulze Lavoisier resurrected the abandoned project. (The Du Pont de Nemours family emigrated to America and founded the successful chemical industry, even toying with the idea of naming their Delaware gunpowder factory Lavoisier’s Mills.)

Years slipped by as Paulze Lavoisier tried to persuade one of Lavoisier’s collaborators (the man inside the rubberised suit in Figure 25) to write a preface condemning Lavoisier’s persecutors. Since he refused, she provided her own short, unsigned preface, which was designed to reinforce Lavoisier’s arrogant boast that the new chemistry had been devised by him alone: ‘elle est la mienne,’ he had written – ‘it is mine’. She distributed copies to Paris’s leading men of science, and accolades poured in for France’s scientific icon. Even one of Lavoisier’s former opponents commented that ‘The name of Lavoisier is a greater recommendation for these new memoirs than all the praise that we could give them.’22

The Memoirs finally appeared in 1805. No coincidence, perhaps, that this was the year she married her second husband, the American Benjamin Thompson, an expert on the physics of heat and light. In Figure 29, he is the man with a bulbous nose standing by the door to the right of the stage. Like Lavoisier, Thompson was committed to finding practical applications for his scientific research; as a reward for his work to help the poor in Munich, he had been elevated to Count Rumford. Ostensibly the ideal bridegroom, he courted Paulze Lavoisier for four years, as they visited each other’s homes and toured round Europe together. At last he succeeded in defeating other suitors. ‘She appears to be most sincerely attached to me,’ Rumford wrote to his worried daughter, ‘and I esteem and love her very much.’23

But only months after the wedding this romantic relationship disintegrated, culminating in an explosive row when he locked out some of her friends and she took revenge by pouring boiling water over his carefully cultivated roses. What went wrong? Rumford called Paulze Lavoisier ‘a female dragon’, a ‘tyrannical, avaricious, unfeeling woman’; his last six months with her were, he moaned, ‘a purgatory sufficiently painful to do away the sins of a thousand years’.24 Her version of events has not survived, but was undoubtedly different. The evidence that does exist suggests that much of the blame lay with him. Even Paulze Lavoisier’s step-daughter – not the easiest of relationships – found her charming and easy to get on with. In contrast, several contemporaries criticised Rumford for being an arrogant, condescending and tactless man. Although he dispensed help to the needy, they sniped, he obviously despised them.

Money was definitely a source of strife. She owned a vast fortune, whereas he was struggling to survive on his Bavarian pension. Rumford eventually walked away with a divorce settlement equivalent to well over a million dollars – a gold-digger, sneered the satirists. Paulze Lavoisier’s intellectual prowess also came between them. Instead of the French concept of sexual complementarity, Rumford held an Anglo-American view of how women should behave. At first he boasted about his new wife’s cleverness and the magnificent soirées that she threw, but he rapidly became angered by her independence and her extravagance with her own money.

Once disentangled from Rumford’s oppressive regime, Paulze Lavoisier returned to Paris and a further twenty-seven years of scientific entertainment and discussion. She entertained two or three times a week: a small select dinner on Mondays, open house on Tuesdays, and frequent Friday evenings of music and conversation. Men of science, artists and poets, foreign visitors – all were invited to mingle at her salon, which was renowned not only for its diversity, but also for its freedom of thought.

‘You have to have lived under the vacuum pump to appreciate the luxury of breathing,’ reminisced one admirer. Well into her seventies, Paulze Lavoisier still supervised the food and the dancing, but also cross-examined her guests about their work. Except for Lavoisier’s absence, it was like re-entering the eighteenth-century world of polite conversation, almost as if the Revolution had never happened. But Lavoisier never fully left her – David’s double portrait (Figure 24) dominated the drawing-room where, curled up on a love-seat, she welcomed her visitors with a disarming mixture of rudeness and politeness.25