From now on we move northwards into western and central Europe to investigate patterns of personal health and hygiene from the medieval period onwards through to what later Europeans triumphantly called the early modern and modern world—finally putting the economic and demographic disasters of the fall of Rome well behind them. The ‘civilizing process’ that seeped through cash-strapped Europe in these medieval and early modern centuries was in effect the slow escalation of domestic luxuries, spread thinly over more ancient ways of subsistence life—hut life—that endured well into the twentieth century. Apart from the economy, the Church, education, and baths, the greatest single difference in the physical regime of medieval personal hygiene (whether because of tribal history, northern geography, or Christianity) was probably the development of underlinen and the close-fitting tailored garment, either of which can trap the body’s evacuations in a layer above the skin, allowing fetid bacterial decomposition to take place; elsewhere in subtropical Eurasia robes and loose clothing remained the norm.

On the face of it, there is every justification for the old-style textbook descriptions of swarming lice and manure-like stenches in medieval life, but the closer you look, the more it seems an exaggeration. Like their biological ancestors medieval people certainly groomed themselves, and—so it seems—a great number of them tried to be as well groomed and clean as it was individually possible to be. They improved their houses and their manners, dressed well, knew their medical regimens, and used baths and cosmetic care. To say that medieval faces, hands, and bodies were always dirty, their clothes tattered and evil-smelling, or that the rushes on the floor were always greasy would be to condemn generations of careful and hardworking medieval housewives, and the honour and dignity of their households.

Using the many available sources from the highly visible European upper ranks to reconstruct post-Roman European domestic life is rather like trying to reconstruct a whole society from ‘society’ magazines in c.AD 2000—you miss 90 per cent of the population.1 But even if the very rich were the tip of the iceberg, what they did and had many others would have aspired to. So far as the rich were concerned in c.AD 800, the long ‘Romanesque’ party had only just begun.

The manners and customs of Charlemagne’s court were part-Frankish, part-Christian, and part-Roman. The strongest influence on the dress and manners of his courtiers was wealthy Christian Byzantium, where ceremonial dress and court etiquette held the eastern Empire together. Charlemagne himself liked to fight and feast with his bards and his family gathered around him, but also relaxed in Roman style. He wore Frankish costume with underlinen, bound leggings, a knee-length tunic, fur jerkin, a long military cloak, and was bearded and moustached; but definitely rejected any tattooing on his body ‘like the pagans who obey the notions of the Devil’. Nor did he wear gilded boots with laces ‘more than four feet long’, scarlet wrappings round his legs, floor-length embroidered tunics, or the new style of bright blue or white (or striped) short cloaks to the waist: ‘what is the use of these little napkins? I can’t cover myself with them in bed. When I am on horseback I can’t protect myself from the winds and the rain. When I go off to empty my bowels, I catch cold because my backside is frozen.’ When Charlemagne died in 816, his tutor and lifelong friend Einhard wrote an insider’s account of the reign. Among other things he especially noted his great fondness for thermal baths:

He took delight in steam-baths at the thermal springs, and loved to exercise himself in the water whenever he could. He was an extremely strong swimmer and in this sport no one could surpass him. It was for this reason that he built his palace at Aachen and remained continuously in residence there during the last years of his life and indeed until the moment of his death. He would invite not only his sons to bathe with him, but his nobles and friends as well, and occasionally even a crowd of his attendants and bodyguards, so that sometimes a hundred men or more would be in the water together.2

Einhard was the architect of Charlemagne’s new Romanesque villa palace in Aachen, built next to his Byzantine chapel, and had presumably engineered the link between the palace and the hot springs that archaeologists found later, providing the luxury of heating throughout the building.

A new courtly honour system known as courtesie (courtesy) spread rapidly via the Frankish courts throughout northern and southern Europe. Clerical courtly tutors had from the beginning used the Roman canon of educational self-discipline (notably Cicero) to persuade the young offspring of the nobility to curb their barbaric ways, and to inculcate propriety, decorum, temperance, and all the other noble virtues—listed in one medieval encyclopedia as: ‘shamefastnesse … trouth … confidence … suffereance…stablenesse…pacience…devotion…truthfulness… benignity… wisdom … chastity… faire speech’. Being‘suave of speech and manner, courtly in love-making’ (with the accompanying natty dress code) became the fashionable hallmark of medieval nobility and rank, especially among the young.3

Along with courtliness came physical refinement. Early manuscript books on household duties and manners, used for training table and body servants, covered every possible embarrassing social situation and breaches of social etiquette; this is where all the well-known ‘abominations’ of the medieval body—farting, sweating, spitting, gobbling, sneezing, slurping, burping, etc.—are listed.4 Guest honour rituals like handwashing (donner à laver, offering a wash) at all meals were scrupulously observed; also the washing of the feet of guests on arrival (practised in both abbeys and palaces). A whole raft of complex rituals of courteous etiquette (eating etiquette, linen tablecloths, and napkins) radiated out from the meal table—including the development and use of cutlery. For many centuries metal and glass was expensive and utensils were scarce or made of wood. The metal table fork was introduced into Europe by a Byzantine princess at her wedding in Venice in 955; everyone else ate with their hands. By the 1500s only peasants ate with their hands.5

The Roman Catholic Church’s homilies and exhortations on cleanness were constant throughout these centuries, treading a fine line between the virtue of civility and the vice of vanity. Officially, the Church stood as the defender of Roman civilitas, and encouraged civilized ablutions as an obeisance to God; but excessive grooming ‘in the Italian manner’ was condemned, as we see in Notker the Stammerer’s cautionary tale for wide-eyed novice monks of The Deacon Who Washed Too Much:

There was a certain deacon who followed the habits of the Italians in that he was perpetually trying to resist nature. He used to take baths, he had his head very closely shaved, he polished his skin, he cleaned his nails, he had his hair cut short as if it had been turned on a lathe, and he wore linen underclothes and a snow-white shirt … Just how unclean his heart was became apparent by what followed. As he was reading, a spider suddenly came down on its thread from the ceiling, touched the deacon’s head with its feeler and then ran quickly up again … when he came out of the cathedral he began to swell up. Within an hour he was dead.6

Nature, in clerical terms, meant your pious inner nature, not your lowly corporeal self. Baptism and lustral bathing were clerical duties; and since bathing and cleansing were known to be medically therapeutic, providing hot baths, grooming, and clothes for the poor was a righteous and pious act.7 Decent but not lavish clerical grooming regimens, at fixed hours and at fixed seasons, were included in all monastic Rules, and laundries were provided, even though the number of times allowed for ‘shifting’ the clothing was severely rationed. Most monks were clean-shaven and carefully tonsured: the wearing of beards was regarded as lowly or hermit-like. The Church tried very hard to curb public morals and ‘the habits of the Italians’, but only partially succeeded. The constant lure of the hot southern lands, and their wicked sensuous ways, was irresistible to the rest of Europe.

Around the Mediterranean, baths, dancing girls, and Romanstyle feasting had continued within Islamic culture. Few northern courts were as luxurious as the stronghold Norman raiders had wrested from Arab rulers in southern Italy and Sicily during the twelfth century, where the energetically self-cultivated Norman kings Roger I and Roger II spent much of their time enjoying their Arabic hunting lodges, pleasure pavilions, the hot springs in the north of the island, and at their new palace at Zisa (meaning ‘magnificent’ in Arabic). On Christmas Day in 1184 an Arab observer noted that ‘the Christian women all went forth in robes of gold-embroidered silk, concealed with coloured veils and shod with gilt slippers…bearing all the adornments of Muslim women, including jewellery, henna on the fingers, and perfumes’.8 When Roger II conquered Thebes and Corinth in the Peloponnese in 1147, he had carried off all their stock of silk cloth, along with all their craftsmen and looms, to strengthen his conquered Arab cloth industry (which included the silk workshops of the royal harem, the Tiraz, at Palermo—another custom which the Normans had ‘appropriated with enthusiasm’).9

Islam also undoubtedly influenced the twelfth-century courts of Anjou and Aquitaine across the Mediterranean in Provence—a hotbed of ‘courtly love’ and the sensuous clothing that was the badge of the new romantics. All tribal courts had their poets or bards to entertain them at the feast, and courtly romantic lais (lays) from the poets of southern Provence spread northwards and became part of the ideology of chivalry; including the court poets who blossomed in fourteenth-century Middle English.10 The Middle English poem Cleanness conjured up a courtly vision of the Lord of Heaven with his perfectly groomed heavenly hosts, in the form of a long sermon on sexual purity, the ‘pearl’ of virginity, and keeping the sabbath clean:

So clean in his court is that king who rules all,

So upright a householder, so honourably served

By angels of utter purity without and within,

Beautifully bright, in brilliant mantles …

But watch, if you will, that you wear clean clothes

To honour the holy day, lest harm come to you

When you approach the Prince of precious lineage,

He hates not even hell more hotly than the unclean …

They shall see in those shimmering mansions,

Who are burnished as beryl, bound to be pure,

Sound on every side, with no seams anywhere,

Immaculate and moteless like the margery-pearl …11

Beds, sex, baths—and nature—were constantly associated in the literature and imagery of romance. Some of the best-known and best-loved images of medieval art are probably the crimson-embroidered tapestries now at the Musée Cluny, Paris, showing a high-born lady with her unicorn (a symbol of virginal purity) experiensing all the delights of the senses, in a series of flowery woodland glades; and in the same collection, and in the same style, is another tapestry illustrating the sensuous outdoor romanticized courtly bath. Courtly baths frequently made their way into stories and poems in scenes of trickery, transgressions, and lover’s trysts. In one French courtly love poem the boiling hot bath prepared for the noble husband was given to the adulterers instead; in the early medieval German poem Parsival, the hero was attended by beautiful maidens strewing the floor with rose petals, and given a truly Homeric knightly bath.12 The twelfth-century Order of the Bath at the Anglo-Norman court was equally romantic and sumptuous: it was created as a lustral bath of purification, signifying their passage into adulthood, for the young elite warriors, the ‘companions of the king’, and lasted two days with the holy evening vigil, the bath, and the ceremonial knighting, followed by games, sports, and feasts. The English Royal Wardrobe bath accounts in the fourteenth century show large expenditures in which the chivalric bed and clothes cost as much as, if not more than, the chivalric bath. In 1327 King Edward III was knighted, crowned, and bathed at the same time:

cloth of gold diapered, to cover his Bath for his knighthood, sheets for the same, and washing his feet, a tunic and a cloak of Persian cloth for his vigil, and tunic, cloak, and mantle of purple velvet, with fur lining the same, and red curtains, with shields of his Arms on the corners for ornamenting his chamber on the night before he received the Order of Knighthood.13

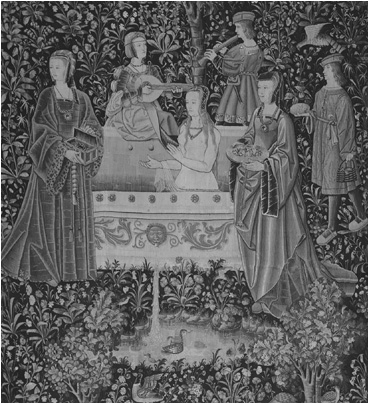

9 Tapestry depicting a heavily romanticized courtly bath in the early 1500s, set in a woodland glade, surrounded by sensuous delights (food, music, sweet smells).

Sicily was an earthly paradise for northerners that did not last. However, the concentration of luxury in the hands of the eager Norman arrivistes set off another chain of events that did last. Frankish Palermo had become the foremost centre of Hellenic and Arabic studies and the commercial and cultural clearing house of three continents, drawing traders from around the southern Mediterranean and scholars dispersed from Alexandria. Just across the water on mainland Italy was a small southern spatown called Salerno, one of Europe’s first medical centres of learning; and the health education that emerged from Salerno and later universities fully restored the old classical advice on how to ‘take care of yourself’.

Salerno was originally a Roman coastal health resort and spa, situated 35 miles south-east of Naples down the coast from Baiae. In 847 Salerno became the port capital of a new Lombard principality, and the first Benedictine medical monks arrived. Over 300 years nine monasteries were established, and Salerno’s three Roman aqueducts were rebuilt, serving a series of public fountains, the old public bathhouses, and private customers en route, some with their own private bathhouses; including the nunnery of San Giorgio, and the bathhouse of the male monastery of Santa Sofia, a large establishment with furnaces and bronze cauldrons and a cold pool, open to all monks, nuns, and visiting clergy that might need them.14 Salerno became renowned for its healing facilities, and, being a port town, treated many damaged, health-seeking travellers, traders, and passing soldiers. By the twelfth century the medical School of Salerno had reached a peak of literary activity, finding and translating into Latin the works of Hippocrates, Galen, and the Alexandrian and Arabic schools, and compiling a new canon of medical authorities known as the Articella (‘Little Art of Medicine’). In addition, the Salerno translation of the plantlore of Dioscorides provided the foundation for later European herbals; the Trotula corpus helped to preserve what remained of classical cosmetics; while the so-called Regimen Sanitatis Salernitanum became the most famous health text of the Middle Ages. But by the end of the thirteenth century Salerno had become a backwater. Islamic centres of learning such as those in Baghdad, Cairo, or Córdoba in Spain, along with university foundations in Padua, Bologna, Montpellier, Paris, and Oxford, had dispersed intellectual talent throughout Europe.15

The new universities fed the early medieval ‘Romanesque’ enthusiasm for literacy, culture, and self-improvement. The message of the health-conscious regimen was strongly promoted by the new university-trained medici, supported by Romano-Islamic classical scholarship such as that of the comprehensive, easy-to-memorize, four-volume Canon of Medicine by Ibn Sina (Avicenna; 980–1037). The physicians were eager to get classical preventive medicine on board alongside their other ‘cures’, and profited well from it: their personally tailored regimens and consilia (letters of advice) were available to anyone who could afford them. Throughout Europe there were growing numbers of manuscript tracts and volumes for general readers on all subjects religious and secular—and roughly 3 to 4 per cent of these were medical works.16 Evidently one had to be ‘wise in science’ at court. Encyclopedic ‘books of secrets’ (such as the famous Aristotle’s Secrets) could be read or memorized in short bursts, as well as being an invitation to further study:

Therefore it is worth that your mekeness have this present boke in the which of all science some profite is conteyned … and in parcell speke couertly [courtly], he made this boke spekying by apparances, examples and signes, techying outward, by littrature, philosophik and phisick doctrine, pertenying unto lordes for kepying of the helth of their bodies, and unto ineffabill profite in knowlechyng of the hevenly bodies.17

In England the earliest medical manuscripts, the old Anglo-Saxon ‘leech books’, were collections of folkloric receipts overlaid with traces of Graeco-Roman medicine; but from the eleventh century onwards the ancient courtly tradition of wise longevity and medical advice to rulers was revived and repackaged in a genre known to us as ‘Mirrors of Princes’, with titles such as ‘The Mirror of Health’ or ‘Regiment for Princes’, largely based on Galenic dietary advice. More rare and expensive were the hand-painted dietary tacuinums derived from Arabic humoral medicine—medical calendars on large vellum pages, similar to the well-known ‘Books of Hours’, painted with brightly coloured and gilded courtly pictures of the correct monthly regimes for food, drink, and ‘the six non-naturals: ‘the six things which are needed by every man for the preservation of his health, about their exact use and effects … we shall insert all these elements into simple tables because the discussions of sages and the discordances of many different books may bore the reader’.18

The Regimen Sanitatis Salernitanum typified the genre of small popular books that became simply known as ‘regimens’—the basis of public health education for the next eight centuries. With 240 different editions by 1846, the first ‘Salerno’ Regimen was written (or copied from Arab sources) in Spain in the late twelfth century, and was gradually extended into a jocular health poem, with up to 363 verses. It steadily progressed through the dietetic imbalances of each Galenic humour, matching them with their opposite therapies. These consisted almost entirely of endless varieties of foods (including herbs) and drinks, with their qualities enhanced by cooking and spicing: light foods versus heavy foods, hot foods to counter cold diseases, cold foods to counter hot diseases. All extremes of intake were condemned as gluttonous and weakening, and any humoral ‘plethora’ (excess) was relieved by bleeding, baths, and exercise.

It was via these regimens that the morning grooming session was institutionalized in medieval life. The morning regimen in the Salerno Regimen (and all other later regimens) was always the most elaborate: firstly, wake at the proper hour (not too much or too little sleep, with more sleep in the winter than in the summer); secondly, clear the evacuations by getting rid of the waste products (going to stool), by clearing the nose, throat, and mouth (sneezing, coughing, spitting, sighing, singing). Then cleanse the night residue from the eyes, face, hands, and limbs (by washing and sluicing, or dry-rubbing with cloths) and clean the residue from the teeth (by rubbing them with cloth, sage, or other aromatic leaves, or by picking them with resinous wood twigs). Applying scented fumigations and perfumed ointments could also stimulate the body and ‘gladden the spirit’—an important point, from the medieval perspective. It was correct to take a little light exercise in the morning until lethargy was dispersed, the heavy vapours released, and the stomach prepared to digest a moderate breakfast (the main meal being shortly after noon, with a second main meal at the end of the day). In the Salerno Regimen itself, ‘Grasse, Glasse, and Fountains’, seems to be a direct reference to spa therapy:

Rise early in the morne, and straight remember,

With water cold to wash your hands and eyes,

And to refresh your brain when as you rise,

In heat, in cold, in July and December.

Both comb your head and rub your teeth likewise:

If bled you have, keep coole, if bath keepe warm:

If din’d, to stand or walke will do no harm

Three things preserve the sight, Grasse, Glasse, & Fountains,

At eve’n springs, at morning visit mountains.19

But even in merrymaking temperance should always prevail: ‘wine, women, Baths, by Art of Nature warme, us’d or abus’d do men much good or harme’. After the Black Death in 1348, manuscript health advice poured onto the market, going well beyond the range of the Salerno prototype: ‘little books’ of health regimens for plague, pregnancy, childcare, travel, sea voyages, or army campaigns.20 In late medieval England at least six regimens or ‘dietaries’ were regularly copied out, including Lydgate’s Dietary and John of Burgundy’s Regimen, of which there are nearly fifty surviving copies.21

In the 700 years between c.800 and 1500 the urge for constant domestic improvement is visible in the steady separation and multiplication of spaces—something we now recognize as a sign of increased personal refinement. For families that had achieved that extra economic margin, rooms were added, others were divided, second storeys added, window-bays and chimneys invented, and ‘dirty’ service areas separated and put out of sight, usually in outdoor yards or courts. From the eighth century onwards water engineering had become an architectural essential for the wealthy and self-confident church foundations. Monasteries had rows of latrines, their lavatoria (washrooms) were large, and they often handed on their considerable expertise to the local nobility, or town councils.22 Where money and expensive stonework was no object, external drop-latrines with indoor seating were loved for their convenience and were installed in most new-built castles (even the most isolated knightly residence in Wales in the 1450s required an indoor latrine for its guest bedrooms); larger castles had up to twenty latrines, sometimes arranged as three-and four-seaters. England’s King Edward III (1327–77) had hot and cold running water installed in two of his palaces.23 For the rest of the population, stone-built conduits and drop-latrines were rare, and the old dry sewage system sufficed. In the country, cesspits and middens were relatively easy to manage; in town they had to be regularly emptied and scavenged by the local authority.24

Inside the medieval bedroom the ‘close-stool’ discreetly enclosed the evacuations, while the simple ‘jerry’ was pushed underneath the bed. It was also at this time that the fixed stone washbasin, or laver, with a can of water hanging above it and a cloth hanging by, reappeared as a common domestic fixture; along with the portable washstand; and the portable wooden bathtub made from a sawn half-cask, lined with linen cloth, possibly with a richer fabric draped over an iron hoop above, making a draught-free private enclosure, or private grooming zone. The new enclosed bed recesses, or personal garderobes (dressing closets), were like the new bay-window recesses that became popular in many chateaux—they both created a separated intimate space. Two chambers, a garderobe, a private oratory, a study closet, and a ‘generous provision of latrines’ was the ideal logis, or private suite, in late fourteenth-century France.25

Most grooming would have taken place on or near the bed, wherever it was situated. The bed was usually the focal point of the main living room on the ground floor; but if the household was really wealthy, it would be in a chamber above. The bed was easily the largest display piece in the medieval house, a major item of expenditure, and was usually lifted up on a dais, with heavy curtain drapes that were as much to display the cloth as for privacy or keeping out draughts. Following Roman precursors, many types of tall wooden furniture were developed in Europe—stools, benches, chairs, tables, sideboards, and cupboards, in a proliferation of styles—which lifted the body and other objects high off the floor and away from the dirty or dusty surfaces below.26 Wooden floors in upper storeys and bedchambers could be covered with straw matting or rugs; ground floors were kept strewn with hay, rushes, sand, or other absorbent materials—although with more funds, more resources, you could have a stone, wood, or tiled floor, as many wealthier households did.

Cloth was one of the great new staple trades of Europe, and medieval culture is inconceivable without it. More work now went into one piece of cloth, ornamented with deep dyes, precious stones, and minute embroidery, than ever before. For the housewife pure white linen was one of the most coveted luxury domestic products, requiring yet more careful preserving and cleaning. In Christine de Pizan’s sermon for laywomen The Treasure of the City of Ladies (1405), virtuous women should have

fine wide cloth, tablecloths, napkins and other linen made. She will be most painstaking about this, for it is the natural pleasure of women [to be] not odious and sluttish, but upright and proper… she will have very fine linen—delicate, generously embroidered and well-made … [and] will keep it white and sweet smelling, neatly folded in a chest; she will be most conscientious about this. She will use it to serve the important people that her husband brings home, by whom she will be greatly esteemed, honoured, and praised.27

Underlinen was now standard. During the Roman Empire, Tacitus had noted that the ‘wild tribes’ of Germania thought it ‘a mark of great wealth to wear undergarments’; only a few centuries later linen garments were worn more or less regardless of social rank—linen shirts, gowns (cottes), leggings, trousers (braises), caps (coifs), and veils—even if there was no expensive outer cloth to go over them. The only time linen was not worn was at night.28 If the grooming was good, and the underlinen regularly ‘shifted’, the vermin and dirt load would be significantly reduced, and could be controlled.

‘Shifting’ linen was obviously not a problem for anyone of high rank: Edward IV’s court accounts show regular money given for the ‘lavender-man’ (the launderer or washing-man) to obtain ‘sweet flowers and roots to make the king’s gowns and sheets brethe more wholesomely and delectable’. But shifting his shirt and picking out vermin from the seams of his clothes was a major chore for the poor student Thomas Platter, in Germany in 1499: ‘you cannot imagine how the scholars young and old, as well as some of the common people, crawled with vermin … Often, particularly in the summer, I used to go and wash my shirt on the banks of the Oder… whilst it dried I cleaned my clothes. I dug a hole, threw in a pile of vermin, filled it in, and planted a cross on top.’ Delousing was more usually done by wives, mothers, and intimates in the slow leisured hours—something that perhaps Platter, like other urban scholars and apprentices, had left behind with his faraway family. A rare description of delousing customs in the French village of Montaillou was fleetingly captured in a fourteenth-century Inquisition testimonial:

Pierre Clergue had himself deloused by his mistresses … the operation might take place in bed, or by the fire, at the window or on a shoemaker’s bench … Raymonde Guilhou also deloused the priest’s mother, wife of old Pons Clergue, in full view of everybody in the doorway of the ‘ostal’, retailing the latest gossip as she did so. The Clergues, as leading citizens, had no difficulty in finding women to relieve them of their insect life …29

Delousing was rarely recorded as minutely as that. A single fifteenth-century manuscript shows a well-dressed older woman brushing the downturned head of a young man outside in a garden with a large hand-brush, with the lice flying into a bowl he is holding. In one medieval romance a nobleman enters the damsel’s chamber and removes his shirt so that they can scratch him with combs made of wood, bone, and ivory ‘with two rows of teeth’, and brush his hair with their ‘small brooms’. It seems that the privacy of this sort of bedroom activity was well respected; a well-known passage from the fourteenth-century bourgeois classic The Menagier’s Wife gives some timeless advice:

Whereof cherish the person of your husband carefully, and, I pray you, keep him in clean linen, for ‘tis your business … and nothing harms him because he is upheld by the hope he has in his wife’s care of him on his return … to have his shoes removed before a good fire, his feet washed and to have fresh shoes and stockings, to be given good food and drink, to be well served and well looked after, well bedded in white sheets and nightcaps, well covered with good furs, and assuaged with other joys and amusements, privities, loves, and secrets, concerning which I am silent; and on the next day fresh shirts and garments. Certes, fair sister, such service maketh a man love and desire to return to his home and to see his goodwife and to be distant with other women.30

10 Bedbugs and head lice—a rare illustration of these ubiquitous bugs from the medieval encyclopedia Hortatus Sanitatis.

It has long been thought that Trotula was a woman physician working in Salerno who wrote a famous book on cosmetics; but recent detective work has proved that this was a myth perpetuated in the 1544 edition by a humanist doctor, Georg Kraut. Like so many medieval popular works, the corpus of work known as The Trotula was compiled by many different hands. During the twelfth century in Salerno two scholarly tracts, Treatise on the Diseases of Women and On the Conditions of Women, were bound together with a more practical and commercial compilation called Treatments for Women and what may have been a local Salernitan classic, a detailed tract called Cosmetics for Women. Just to clear up a confusion which has long existed, until 1544 the first two were called Trotula Major and the second two, Trotula Minor; but both were pillaged and adapted in various ways, with a surge of editions in the fourteenth century, including pocket-sized vernacular translations into almost all European languages. Two further treatises (De Ornatu Mulierum, and De Decorationibus Mulierum) were transformed into the highly popular Ornement des dames (‘Adornment of Women’).31

The Galenic, Alexandrian, Methodist, and Arab techniques found in European cosmetic literature were pale reflections of the knowledge available in the Arab Empire, where cosmetic treatments were well respected. Al-Razi (Rhazes; 841–924), Ibn Zuhr (Avenzoar; 1091–1161), Avicenna, and many others drew on a technical revolution in Arabic chemistry that included mastering the art of distillation, with obvious uses in perfumery and medicines, and the incorporation of exotic herbs, vegetables, minerals, and spices from the Middle East, India, China, and South-East Asian trade routes.32 Women had long practised practical medicine of the sort that kept men and women alive, without benefit of literacy; but from this time onwards, following the introduction of university-based medical licensing (and given the Christian injunction for women to ‘be silent’), practical domestic medicine goes to ground and the historical record does indeed fall silent—certainly when compared to the new socially stratified public world of the male medici.33 In fact ‘women’s medicine’ was neither particularly hidden nor ‘impenetrable’ to most people in the semi-literate medieval period; indeed it could be said to have been in its heyday. What we have in the Trotula manuscripts is a brief snapshot of the private domain of the bedroom, where women traditionally ruled, ministered, and suffered, and men submitted (a truth that Christian male authors were loath to admit). For any historian of dermatology and COBS grooming, they are a bright light shone on previously hidden practices, and the remains of classical cosmetic lore.

It is interesting to see just how thorough COBS practical medicine could be. All of the Trotula texts dealt with internal female gynaecological problems (the menses, childbirth obstetrics, womb disorders, infertility) as well as external skin disorders, and skin ‘adornments’. Slicing, picking, or abrading the skin to clean out ‘simple wounds and apostemes’ were part of the cosmetic art; while other, internal complaints were approached through the orifices requiring major and lengthy medical operations, but without any deep cutting through the skin into the body—which was obviously considered far more dangerous and not to be undertaken lightly, i.e. not without sufficient knowledge. One example from On the Conditions of Women, showing what could be done manually for the wandering or ‘dropped’ womb after childbirth, suggests fumigation of the nose and vagina with aromatic spices, giving warm bitter drinks, oiling and warming the navel prior to manipulating the womb ‘to the place from which it was shaken’, followed by baths and steam baths:

Afterward, let the woman enter water in which there have been cooked pomegranates, roses, oak apples, sumac, bilberries, the fruit, leaves and bark of oak, and juniper nuts, and lentils. Then let there be made a steambath, which works very well. For Dioscorides prescribes that there be made for them a steambath of boxwood placed in a pot upon live coals, and let the woman, covered on top, sit on it, and let her receive the smoke inside.34

A dropped womb was a medical emergency; but even begetting a child could be a severe personal problem, for which infertile women traditionally sought treatment at temples, holy wells, and spas. Enhanced attractiveness, using ‘beauty’ recipes for seduction, was a tried and test method; but intimate knowledge of the workings of the womb, vagina, and genitalia led naturally to treatment of the problems of intercourse—including sexual hygiene. One particular Trotula treatment (suppressed in later editions) dealt with severe and unpleasant vaginal odours: ‘There are some women who because of the magnitude of their instrument and its severe odour are sometimes found unpleasant and unsuitable for intercourse.’ The practical remedy was to constrict the vagina with a scented astringent wash, prior to intercourse, and to apply a sweet powder to her chest, breasts, and genitalia, as well as washing her partner’s genitals and drying them with a cloth sprinkled with the same powder.35 For women ‘in whom pieces of flesh hang from the womb… note that this happens to them from semen retained inside and congealed, because they do not clean themselves after intercourse. These women we always foment with a decoction of hot herbs.’ It is probable that this type of practical sex-medicine went into the barber’s (and surgeon’s) trade, but no higher; in the eighteenth century the treatment of sexual disease (venereology) was a hidden or ‘quack’ male medical specialism, albeit with a high-class clientele.36

Note the assumption that women should clean themselves after intercourse. Note too the application of complementary remedies to men. There was no apparent gender divide in the treatment of external skin disorders on the other, more neutral parts—the hair, face, hands, eyes, ears, feet, breath (‘stench of the mouth’), or underarms:

For lice which arise in the pubic area and armpits, we mix ashes with oil and anoint. And for lice which are around the eyes, we should make an ointment suitable for expelling them and for swelling of the eyes and soothing them … For scabies of the hips and other parts, a very good ointment. Take elecampane, vinegar, quicksilver, as much oil as you like, and animal grease….37

Bad breath, bad odours, lice, spots, swellings, or genital problems were of course never gender-specific; and skin salves were urgently required for the victims of the endemic and epidemic outbreaks of diseases that gathered pace from the twelfth century onwards. Vast quantities of herbs, oils, minerals, and spices were thrown at the very visible symptoms, making barbers and apothecaries rich in the process. A whole battery of cosmetic medicaments anointed King Edward I of England’s body the year before his death in 1307: ‘282 lbs of electuaries; 106 lbs of white powder; ointments, gums, oils, turpentine; aromatics for the bath; a special electuary containing ambergris, musk, pearls, gums. Gold and silver medicated wines; a plaster for the king’s neck; a drying ointment for his legs and more for anointing his body’.38

The Trotula texts made the basic assumption that women readers would wish to ‘cleanse themselves of all impurities’ and were repulsed by all sordidness, and gave large numbers of recipes for the ‘clarification’ of the skin, especially the face, neck, hands, and breasts. The ideal complexion was red and white, with healthy red gums and lips, white teeth and skin, and clear eyes; the hair could be dyed black or blonde, and was combed through frequently with perfumed powders or waters. But On Women’s Cosmetics, which had a very authentic southern classical Arab flavour, started with the old full-body makeover—total depilation:

In order that a woman might become very soft and smooth and without hairs from the head down, first of all let her go into the baths, and if she is accustomed to do so, let there be made for a steambath in this manner, [just like women beyond the Alps]. Take burning tiles and stones, and with these placed in the steambath, let the woman sit in it. Or…place them in a pit made in the earth. Then let hot water be poured in so that steam is produced, and let the woman sit upon it well covered with cloths so that she sweats. And when she has well sweated, let her enter hot water and wash herself very well, and thus let her exit from the bath and wipe herself off well with a linen cloth. Afterwards let her also anoint herself all over with this depilatory which is made from well-sifted quick-lime [a cooked recipe of ‘leaves of squirting cucumber’, almond milk, quicklime, orpiment, galbanum, oil, and quicksilver, perfumed with the powders of mastic, frankincense, cinnamon, nutmeg, and clove] … Take care, however, that it is not cooked too much, and that it not stay too long on the skin, because it causes intense heat. But if it happens that the skin is burned from this depilatory, take populeon with rose or violet oil or with the juice of houseleek, and mix them until the heat is sedated.

This was followed by a lukewarm bran bath, and another anointment with henna and whites of eggs: ‘This smoothes the flesh, and if any burn should happen from the depilatory, this removes it and renders it clear and smooth … Then let her rinse herself with warm water, and finally with a very whiten linen cloth wrapped around her, let her go to bed.’39

Body depilation was a day-long job; the facial depilatories were put on with a spatula for an hour; the facial compresses overnight. The face-whitening oils with white powders or white lead were for daytime use, with the rouging of lips and cheeks to ‘make red a whitened face’. Saracen women often ‘dyed their faces’ by mixing the two—‘a most beautiful colour appears, combining red and white’—to make a pink day cream. This particular tract continued with advice for stinking breath from putrid gums, fissures of the lips, facial abscesses; and a vaginal constrictor ‘so that a woman who has been corrupted might be thought to be a virgin’, in the form of a powder that also helped check nosebleeds and excessive menstrual flow.

It was a very short step indeed from medical treatment to beauty treatment; from infection to disfigurement—‘veins in the face’, or ‘freckles of the face’, or ‘removing redness of the face’. It was not one that any Arab (or indeed Indian) physician would have thought worth considering; but Christian Europe had brought its own particular ascetic philosophy to the study of the cosmetic art and craft. The French surgeon Henri de Mondeville (1260–1325) was one of the first to take a high moral tone, in print, about cosmetic care: ‘It goes against God and righteousness; it is not ordinarily the treatment of an illness, but something that goes outside of this with the intention of concealment or disguise.’ His pupil Guy de Chauliac (1300–68) went further and confined surgical cosmetic care only to serious disorders and defects of the skin, in his influential textbook Chirurgia Magna (1363).40 Post-Black Death medical licensing, followed by development of the medical guild system, formally drew the line between the university-educated surgeons and craft-trained barbers, and the cosmetic corpus itself underwent a subtle transformation. The professional aspects of gynaecology and cosmetics were emphasized—‘the address to female readers was one of the first elements to go’—and the later Trotula manuscripts, it seems, were more often owned by barber–surgeons, and noble households, than noble women. Gradually, barbering and cosmetic work was taken out of surgery. By the sixteenth century the detailed sections on cosmetics given by earlier medieval authorities were deemed ‘unnecessary’, and after Kraut no further editions of the Trotula were required.41 It was a long process. The ordinary general-purpose barber–surgeon would not willingly dispense with such a lucrative trade, especially one so close to the domestic hearth; for as even de Mondeville had admitted, ‘the favour of women cannot be overestimated. Without it one comes to nothing; without it no one can obtain the goodwill of the men …’.

Medical licensing could easily create public resentment if it too severely limited the supply of available healers, or did not reflect the true nature of public demand. Wherever licensing figures are available, it appears that it was the lower-rank practical medical crafts that were highest in public esteem. Licensed medical craftsmen not only had private clients, but could also open up street shops (as in many parts of the world today) that thrived as urban residency increased. In the region of Valencia between 1325 and 1334, just over a half of all practitioners were barbers and apothecaries, in equal numbers; in other cities, all-purpose barber–surgeons made up the bedrock of medical care, and university-trained (theoretical) physicians were always in a distinct minority.42 Even after the Christian conquest of Spain many Muslim doctors continued to practise, got their licences, and were used by Christian and Muslim families; and among them were the traditional Muslim metgesses, women doctors known to be expert at treating eyes, hands, feet, and other parts, presumably in the manner of the Trotula. The 1329 Valencian law excluding women from medical practice should have hit them hard; but because of their popularity (and possibly their rich clientele) they frequently appear to have escaped prosecution, at least at first.43 But the loss of professional prestige eventually affected European cosmetics more permanently. Many of the finer therapeutic details of the classical œuvre must have disappeared at street level—especially, perhaps, the care of the private parts, and the skilful use of massage. Cosmetic care (barbering) became a commercial male craft occupation supported by craft apprenticeship, oral tradition, and random sources of expert knowledge (often tucked at the back of surgeons’ handbooks). Women, who had no access to male barber’s shops or formal education, eventually resorted to collecting, and often publishing, their own books of receipts and sharing them around their friends and family circle. These became incorporated into the well-known receipt book genre that included all housewifery receipts, which lasted well into the late eighteenth century until it was superseded by mass-produced advice literature.

In practical terms the professional demotion of cosmetics may have had fewer repercussions in domestic medicine than we might think, certainly in the medieval period. For example, it hardly dented the popularity of baths; indeed the casual reference to the old Neolithic steam pit shows how easily such a sweat bath could be set up on a patch of land, and how ubiquitous they may have been. The great numbers of different references to baths throughout the medieval sources show they obviously held a special place in medieval life socially, medically, and spiritually. The public baths, in particular, show even more clearly how baths still represented all the old antique pleasures of water, and were genuine communal occasions. From the ninth to the sixteenth century the public hot bathhouses—the ‘stews’ and the thermae—were a large and well-run leisure industry.

We can view the medieval baths culture of northern Europe as being similar to the bathhouse culture of Japan or Finland: it was innocent of any shame. No one blushes for their nakedness in the communal baths and saunas of Japan or Finland. No one blushed in ancient Germany, where, as Julius Caesar noted, ‘both sexes bathe communally in rivers, and display the body mostly naked under small covers of animal hides’. Nor in medieval Europe, where communal naked bathing, and the segregation of the sexes, was only suppressed with difficulty, if at all. Some purity rules in Church law were apparently widely observed, but it evidently failed to change earlier tribal, or customary, laws concerning sexual rights over the body. Regular puritanical attacks on traditional spring carnivals, town brothel-keeping, and communal bathing—in other words against fornication, nakedness, lewd clothing, and baths—seem to have been largely ignored until the sixteenth century. The Church edict of Boniface in 745 forbade joint bathing between the sexes, and a later edict made it a sin to be confessed. An eleventh-century Church Correction Book states: ‘Hast thou washed thyself in the bath with thy wife and other women and seen them nude, and they thee? If thou hast, thou shouldst fast for three days on bread and water.’ But it was not a grievous sin. Much more common was the use of the Church fine; a typical fine for bathing infringements (such as coming into church straight from the bath improperly dressed ‘with naked legs’) could take the form of a pound of wax for the church candles.

Virtually all commentators, approving or disapproving, agreed on the essential innocence of the free manners of the public baths. Some even saw nakedness as a natural right. In one imaginary peasant utopia (bearing some resemblance to the painter Hieronymus Bosch’s visionary Garden of Delights) everyone would be ‘totally free’ of all restrictions, including clothes:

Neither skirts nor cloaks are needed there,

Nor shirts, nor pants at any time:

They all go naked, modest maids and stable boys.

There is neither heat nor cold at any time.

Everybody sees and touches the others as much as he desires:

Oh what a happy life, oh what a good time …44

Defending communal bathing later in the sixteenth century, Ulrich von Hutten said ‘Yes, they touch one another in friendly fashion [but] nowhere can you see women’s honour more clearly than with these people who don’t regulate it. Nowhere is honour stronger than here … They trust one another and live in good faith free and humbly without deception.’ Numerous prohibitive regulations in Germany about naked legs in the street were constantly resisted, according to Wilhelm Rudeck’s classic History of Public Morality in Germany (1905). There was a slow move towards the separation of the sexes in French baths during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, with some towns adopting it up to a century later than others, but even then ‘it was never in practice universal’.45

There were twenty-six guild-run bathhouses in Paris in 1292 (probably an underestimate, just as the supposedly 200 baths in the town of Ulm were probably an overestimate). In Finland, Sweden, Russia, and Germany every village had its bathhouse. The concentration of the old sweat hut tradition in the colder parts of Europe is explained (as in Japan) by their heating qualities: the colder the region, the more their extreme heat thawed out the body (and allowed the wearing of lighter clothes). And the heat that they got up and the fuel that they used (as the Romans also understood) was too valuable to waste on individuals. Family sweat rooms weren’t so difficult to achieve. The original bathhouse of central Europe was centred on the house’s stove, where the hot bread ovens were tapped by a tube that carried steam into an adjoining room; and in towns, the bakeries performed the same functions.46 The many sixteenth-century etchings we have of one-room communal baths in Germany seem to show not only a steam but a hot-tub culture, with many little tubs scattered across the floor, used for different purposes; but there must have been a good heat got up in one wood-panelled room illustrated by Dürer, with a tall ceramic stove, and bathers of all ages lounging naked except for their decorative jewellery and their ornate bath caps.47 Such communal scenes were replicated throughout northern Europe for centuries afterwards, as witnessed by the nineteenth-century French traveller Paul du Chaillu, at a ‘Saturday bath’ in an isolated village in Finland:

There was a crowd of visitors, neighbours of different ages, and among them three old fellows—a grandfather, father, and an uncle—who were sitting upon one of the benches minus a particle of clothing, shaving themselves without a looking-glass. Nobody seemed to mind them, for the women were knitting, weaving and chatting … When the men finished shaving, clean shirts were brought, and then they dressed themselves while seated. The men usually shave once a week, and always after the bath [every Saturday], for the beard then becomes soft … The custom described has come down from olden times; the Norsemen called Saturday, Laudag (washing day) …at present Loerdag, but it is now chiefly observed in the [northern] regions of Scandinavia …48

11 The Women’s Bathhouse (c.1496), by Albrecht Dürer, a companion-piece to his etching The Men’s Bathhouse—vividly realistic examples from the fifteenth–century German genre of public bathhouse scenes.

This customary Saturday bath that was so widespread in various regions of Europe cleaned off the sweat and grime once a week. It was something any respectable Christian citizen might care to do prior to a holy day, and also fitted the religious calendar of Jewish communities. A seventeenth-century (clerical) eyewitness account of the Saturday bath from Basel in Switzerland shows just how medieval villagers had brought their homely habits into the towns:

In the morning the bath-keeper gave a horn blow, that everything is ready. Then the members of the lower classes [and] polite citizens undressed in the house and walked naked across the public road to the bath-house … Yes, how often the father runs naked from the house with a single shirt together with his equally naked wife and naked children to the bath. How often I can see (that is why I do not go through the town) little girls of 10, 12, 14, 16, 18 years, completely undressed, except for a short linen bath-coat (badehr) often torn … They run along the roads at lunchtime, to the baths. And alongside them the totally naked 10, 12, 14, 16, and 18 year-old boys, accompanying these respectable young women.49

There were other family and kin celebrations that the Church also found it hard to control or outlaw, despite the fact that other ancient festivals had been incorporated into the festive Church ‘holidays’. The large numbers of accounts of lying-in baths, marriage baths, and spring carnival baths seem rather to fit earlier customs connected with the rites of Venus (or any other local fertility goddess). They were the bath feasts, the bath parties that slotted naturally into the bathing calendar.

Prenuptial marriage baths and feasts are a worldwide phenomenon, roughly equivalent to our hen nights and stag nights. In Europe they survived well into the twentieth century in Russia, Turkey, and elsewhere.50 In medieval Scandinavia the bridal party was given in the communal hot bathhouse, to which the bride and her female friends would walk in procession, preceded by men carrying jars of ale or wine, bread, sugar, and spices. The guests wore elaborate clothes and jewellery and received bathing hats and bathrobes from their hosts, but disrobing was common among ‘the young men who come with naked legs, and dance in that attire’. By the sixteenth century, European marriage baths had become so expensive that some local authorities imposed restrictions, saying that young couples could not afford them. The lying-in bath was supposed to be more modest and intimate—but not if the lying-in was expensive, like the one Christine de Pizan visited in a rich merchant’s house in Paris:

In this bed lay the woman who was going to give birth, dressed in crimson silk cloth and propped up on pillows of the same silk with big pearl buttons, adorned like a young lady. And God knows how much money was wasted on the amusements, bathing and various social gatherings, according to the customs of Paris for women in childbed (some more than others), at this lying-in!51

The lying-in bath (like the American ‘baby shower’) would have been hosted by the woman herself, for her female friends, her ‘gossips’: in fact her bath companions, since (judging from stories and woodcuts) women apparently did a great deal of socializing in the baths, and often held impromptu parties there, bringing their food and drink with them. The Italian, French, Portuguese, English, and Hungarian natural thermae were in full swing during this period, and in many if not most of them, the situation would have been similar to those described in the thermal town of Baden in 1416, with its two central public baths and twenty-eight private baths:

In some of the private baths, the men mix promiscuously with their female relatives and friends. They go into the water three or four times every day; and they spend the greater part of their time in the baths, where they amuse themselves with singing, drinking, and dancing. In the shallower part of the water, they also play upon the harp. It is a pleasant sight to see young lasses tuning their lyres, like nymphs, with their scanty robes floating on the surface of the waters. They look indeed like so many Venuses, emerging from the ocean … The men wear only a pair of drawers. The women are clad in linen vests, which are however slashed in the sides so that they neither cover the neck, the breast, nor the arms of the wearer… every one has free access to all the baths, to see the company, to talk and joke with them. As the ladies go in and out of the water, they expose to view a considerable portion of their persons; yet there are no doorkeepers, nor do they entertain the least idea of any thing approaching to indelicacy.52

The most expensive bath parties of all were held in royal or aristocratic circles, in private bath suites and thermae. Charlemagne had held court in the thermae at his palace at Aachen, with his advisers and kin sitting around him, up to their necks in hot water. He had deliberately rebuilt the spring for communal bathing; as local legend later had it: ‘At his sole expense immense basins were dug … these baths were open to the indiscriminate use of persons of all classes, and he himself frequently displayed his skill in swimming before his court and a numerous concourse of spectators.’53 Most European hot springs were probably never abandoned locally, regardless of whether or not they attracted the attention of the current rulers, and they began to be developed by local kings in this period, as at Bath, which was supposedly reopened by King Bladud around 800. In Budapest the hot baths were founded by the first king of Hungary, King Stephen, in 1015–27. Aachen (Aquisgranum, now Aix-la-Chapelle) had been developed by the Romans, who had found the hot springs of the area much in use by local tribes such as the Mattiaci, who also settled around the hot springs of Wiesbaden, a few hundred miles down the Rhine valley (a substantial Frankish villa was found in Wiesbaden). In Wiesbaden the hot-water rights were much fought over from 496 onwards, but were eventually claimed by the dukes of Austria. Overlords also of course owned the many cold mineral springs and local holy wells where people were ‘dipped’ rather than bathed; as overlords even the Church could be the proprietors of locally valued hot springs, as they were in Bad Kreuth in Switzerland, or at the Bagni de Vignoli in Italy, where a papal palace was built. Direct ownership of a town bathhouse was a valuable asset, handed down from father to son; wealthy highborn proprietors usually gave it over to another family to manage on franchise, charging them an annual rent, with strict regulations concerning cleanliness and orderliness.54

The overlords were clearly mixing pleasure with politics, and by the early fifteenth century, diplomatic bath feasts were in full swing. In 1446 the bathing arrangements in the Grand Palace of the duke of Burgundy, at Bruges, were overhauled and renewed for the wedding of Charles the Bold and Margaret of York. Steam rooms and barber’s shops were provided for the duke and his guests, but the star attraction was a great bathing basin (probably a cauldron made of metal, like the one in the Salerno monastery) brought to Bruges from Valenciennes by canal; this bath was so large that a hole had to be made in the wall of the palace to accommodate it.55 Essentially, many of these aristocratic bath feasts were used for political purposes, and for the ostentatious display that accompanied them. The accounts of Philip the Good show how he used them to give important guests a good time. Throughout December 1462 the duke gave several banquets in the baths at his palace for most of the local nobility, including one for the ambassadors of the wealthy duke of Bavaria and the count of Württemburg, where he ‘had five meat dishes prepared to regale himself at the baths’. Philippe de Bourgogne hired both the bathhouse and its prostitutes at Valenciennes, ‘in honour of the English ambassador who was paying him a visit’. Nor were noblewomen excluded: in 1476 a reception was given in Paris to Queen Charlotte of Savoy and her court, where ‘they were received and regaled most royally and lavishly, and four beautiful and richly adorned baths had been prepared’.56 The larger bath feasts also often took place outside in the open air; as they probably did at diplomatic parties in Baden in the 1480s, where the hot springs were now hosting a rather more select clientele, not just the townspeople:

From the year 1474 the [imperial] confederation held their great assemblies regularly every summer at Baden with many other visitors attending…. In the summer of 1474 the councillor of Halle, Hans von Waldheim, spent four weeks at the baths, and in his report, highly praised the good society of the place, and in the same year, Princess Eleonora of Scotland [attended], and her court.57

There were certain particular times of the year when the baths became the centre for openly erotic mass revelry: spring carnival time, the time of Fleshly Lust. It was also the Galenic time for bleeding and purging: ‘Spring (Ver) … good for all animals and for the products that germinate from the earth. Dangers: Bad for unclean bodies. Neutralisation of dangers: by cleaning the body.’58 The ‘bucolic’ spring festivals included the wearing of flower garlands and bringing flowers and leaves into the house, and (as in the English May Day) always involved a ritual excursion by youths and maidens into the surrounding countryside. All monthly calendars of scenes from the agricultural year, almost without exception, including the great Très Riches Heures du duc de Berri, show spring—the month of May—as a festive time of lovemaking, bathing, boating, swimming, picnicking, and music-making. The general theme is fertility and rejuvenation, and the rites of youth. The so-called ‘fountains of youth’ scenes, and the outdoor ‘love gardens’ (Liebesgarten) of the German bath houses were favourite etching subjects in fifteenth-century art. So common are these spring calendar scenes that we cannot see them only as scenes of knightly or aristocratic revelry: the local river did just as well if you could not afford the 10 pfennigs it might cost you to enter the most fashionable local baths. Or you might ‘bring out your baths’ in your own garden, or on the front porch. French carnival records—especially court records—show how the local bathhouse featured heavily as a destination for the procession, and as a base for the town or village party to come. It was a natural headquarters for the notorious société joyeuse—the groups of young men that organized the communal charivari.59

Most erotic spring bath evidence stood little chance of survival during the succeeding centuries—such as Count von Edelstein’s infamous painted fresco Of Fleshly Lust, which he enjoyed in his bathhouse at Wiesbaden in the 1390s, and which was apparently ‘shocking through its fleshliness, and soaked in sensual voluptuousness’. It showed scenes from the famous Wiesbaden Festival—which, in a reversal of the urban springtime exodus, was obviously the time when rural inhabitants came into town from the countryside to have some carnival fun. The festival itself was observed with pious horror and sadness by a visiting monk:

Everyone brings food, drink, money, strange dresses are worn along the way. In anticipation of enjoyment they are already playing, singing, gossiping, as people who would expect the absolute epitome of happiness to come. When they arrive at the baths, the food is spread out … In the baths they sit naked, with other naked people, they dance naked with naked people, and I shall keep quiet about what happens in the dark, because everything happens in public anyway…

Of course he made sure he stayed until the bitter end:

The coming and the going of this ridiculous festival is not the same. When, after everything has been eaten, the cupboards go back empty, the pouches empty of money, they regret having wasted so much money…. Meanwhile they return home, their bodies are washed white, their hearts are black through sin. Those who went there healthy, come back contaminated. Those who were strong through the virtues of chastity return home wounded by the arrows of Venus … And so they experience through such events, when they return, the truth of the sentence that the end of all fleshly lust ends sadness.60

The salacious bath picture that shows a king and a bishop holding the keys to ‘the stews’ was not far wide of the mark.61 Hot baths never lost the taint of the brothel pinned on them by puritans for the good reason that they were the favourite—indeed licensed—places for sexual seduction, sanctioned by the elders of the community. The medieval municipal bathhouse shared this job with the medieval municipal brothel (in Germany the Frauenhaus, in France the maison des fillettes), where the public women based their trade. The town authorities seemed to have regarded both the baths and the brothels as a necessary outlet for the energies of the town’s young men, and simply tried to control them. According to one recent history of prostitution: ‘Everywhere that their operation can be clearly ascertained, the étuves [stoves] served both the honest purpose of bathing and the more “dishonest” one of prostitution. This continued to be true in spite of innumerable regulations against receiving prostitutes in the bathhouses or specifying hours or days …’62 Bath prostitutes and bath-keepers were thus as firmly regulated as brothels. In medieval London the city’s main eighteen hot baths in Southwark were on land owned by the bishop of Winchester, instantly giving the prostitutes who traded there the name Winchester Geese. In 1161 the Southwark stews were newly regulated—not closed (for they were an ‘old custom used for times out of mind’), but reorganized to ensure fair trading and orderliness. The women were to be free to come and go; they were not to open on Sundays; no more than 14 shillings’ rent for each women’s chamber; no nuns; money to be paid for the full night; no women with venereal diseases—and no food on the premises. This last must have been a great blow, precisely calculated to send the party trade elsewhere, but was probably not observed for long.63

By the fifteenth century, bath feasting in the many town bathhouses seems to have been as common as going out to a restaurant was to become four centuries later. German bath etchings from the fifteenth century often feature the town bathhouse, with a long row of bathing couples eating a meal naked in bathtubs, often several to a tub, with other couples seen smiling in beds in the mid-distance. In one well-known version, the bathers sit in curtained-off, two-seater baths, being served their food on a cloth-covered table alongside the bath. Guests enter, and waiters scurry to and fro.64 The illustrations show the high-waisted, low-cut, breast-exposed styles for women that had become fashionable, with the men wearing very short doublets and hose, with buttocks and codpieces exposed. The medieval bathing party was then very nearly at its height. ‘Twenty five years ago, nothing was more fashionable in Brabant than the public baths,’ said Erasmus in 1526; ‘today there are none, the new plague has taught us to avoid them.’

The etchings and literature of the early 1500s captured a way of life that was just about to go into a steep decline. In England, Henry VIII closed the stews of Southwark and Bankside in 1546; the brothels and stews of Chester were closed in 1542. In France the four steam baths at Dijon were suppressed in 1556; in 1566 they were closed throughout the Duchy of Orléans, while those at Beauvais, Angers, and Sens were gone by the end of the century. In Paris there were ‘only a handful by the end of the seventeenth century’.65

No single cause is sufficient to account for the disappearance of such deep-rooted customs. Wilhelm Rudeck suggested reasons that were primarily material, and economic, citing syphilis and the rising cost of fuel as the two main factors that put bathhouses out of business in Germany.66 Recent historians have preferred to emphasize the fear of the plague, poisonously infiltrating steamed-open bodies, and this certainly fits with the reappearance of severe epidemic plague in the sixteenth century; but then why did the baths not disappear earlier, after the Black Death? Rudeck probably underestimated the effect of the general decline of rurally based peasant culture; and the popular urban roots of the moral Reformation, especially in certain areas of growing population. There were changes in the political climate that either put puritanical religious reformers, or activists of the Catholic Counter-Reformation into power, many of whom were ascetics who were likely to view the bathhouses as hotbeds of sexual uncleanness and political dissent.

Pressure from growing urban populations meant that, by the end of the fifteenth century, the bathhouses (like the bawdy houses) were increasingly seen as places of lawlessness and social disorder; they disturbed the regular inhabitants, breaking the fragile trust of the community, and the numbers of arrests and prosecutions grew.67 But arguably it was the arrival of acute epidemic syphilis in 1493 which achieved what endemic plague, rising costs, religion, or lawlessness had failed to do: it closed them immediately and peremptorily, and when or if they reopened, they were never the same again. The innocence was gone.

Syphilis hit at the heart of the body culture that featured so strongly in the baths and festivals. Grossly disfiguring to the face and private parts, and highly contagious, it created an unprecedented fear of sexuality, and also polluted the act. You had to check, now, that the vessel was ‘clean’. Rottenness could be hidden beneath superficial beauty. New ways and new avoidances had to be learnt, and learnt fast:

Take heed of the perils of lovemaking

And change your ways accordingly…

Avoid blotchy folk, and don’t despise those who are loyal partners,

Stick to sweethearts, who are not to be lightly dismissed.

But make sure you don’t start the job

Without a candle; don’t be afraid to

Take a good look, both high and low,

And then you may frolic to your heart’s content.68

Better still, remain chaste until marriage: ‘keep thee clene unto the tyme thou be maryed’. The only true surety of cleanness was prenuptial virginity, for both men and women. The printed broadsheet The Wedding of Youth and Cleanness (1509) showed how ‘Virtue conquers Sensuosity and is rewarded by Love.’ For those who had not yet got the disease, they should avoid infected people ‘as one avoids contact with a leper’. A good regimen, without Venus, was essential; or if with Venus, a meticulous hygiene of the genital areas was required at all times—bathing with hot water and wine (or vinegar), using herbal washes, dusting with mineral powders, and ‘above all, avoid using towels belonging to prostitutes’.69

The offspring of an ‘ancestral spirochete’ (treponematosis) that is now thought to have been endemic worldwide from ancient times, syphilis suddenly mutated into a far more virulent form in the Spanish Atlantic ports in 1492 and reached central Europe by 1502, before travelling on to India, the East Indies, Japan, and all colonial trading islands. Eventually it retreated, and over the succeeding five centuries became endemic, dwindling into a curiosity, then into ‘silence and contempt’, leaving a huge legacy of syphilitic wives and children throughout the world, before finally dropping off the list of scourges in the mid-twentieth century. In the worst cases, the syphilitic tubercles were followed by a tumour that bored into bone tissue and then liquefied, exposing the bones and eating away at the nose, the lips, the palate, the larynx, and the genitals.

Syphilis (unlike plague) was not a disease of poverty, but raged equally among the nobility, royalty, and clergy, partly due to the wide sexual licence given to aristocratic youth who visited brothels for their education—with the result, said Montaigne (1533–92), that ‘we are taught to live when life has already passed us by. A hundred schoolboys have caught the pox before they have studied Aristotle on Temperance.’70 But anyone was at risk; and syphilis was emotionally described in real-life patient experiences pouring out of the new printing presses, the start of a long tradition of popular self-help medical autobiographies. In 1498 a young canon, Josephus Grunpeck, wrote a most horrifying and graphic personal account in which he described how he worked his way downwards from fashionable physicians before finally, in desperation, seeking help from ‘louts and uneducated folk’—to whom with hindsight he gave due credit:

These uncouth men, whoever they were, cesspool emptiers, rubbish collectors, cobblers, reapers and mowers, had to lance the tubercles, those harbingers of countless horrible and incurable wounds, and thus drive away or suppress the consumption with pills, ointments, creams, or some other such medicine; and it is undoubtedly due to the zeal, industry, and application of these men … that I, afflicted for the second time, and very severely at that, with this illness, recovered my forces sufficiently to resume my usual activities.71

Syphilis had a profound effect on the trades of the barber–tonsors and barber–surgeons. In a tradition probably dating back to classical times, barbers’ back rooms and yards (if they had them) were used for minor surgery and baths; the front of the shop dealt with hair-cutting and shaving, and the jovial grooming atmosphere encouraged the sale of books, drinks, and pharmaceuticals on the side. To start with, as Grunpeck’s experience shows, long-term venereal treatment could be done by anyone, certainly by any barber; but it was later regulated on the grounds that it was too ‘perilous’ to keep the (clean) grooming and (unclean) curing activities together. The English 1540 Act that joined the Barbers’ and Surgeons’ companies gave the educated barber–surgeons (and of course the physicians) the lucrative monopoly on treating venereal disease, and excluded the older general handymen, the barber–tonsors (as also happened in France). But the English Parliament also made it quite clear that the ancient practices of mutual aid and empiric medicine should not be allowed to disappear, by promptly passing the so-called Quacks’ Charter in 1542–3 that legally enabled anyone to practise medicine, if they could ‘so help their neighbours and the poor’.72

Meanwhile the baths, bathsmen, and their guilds disappeared completely, along with the regulated stews. As was realized by many at the time, the closure of these licensed stews concentrated in the central parts of major towns was a public health disaster. In London old leper hospitals isolated some of the syphilitic poor, but the main means of transmission—the public prostitutes—were dispersed, and went ‘private’: ‘Since those common whores were quite put down, a damned crue of private whores are growne…’. The prostitutes of London served a town that had one of the fastest-growing populations in Europe, and the bawdy houses quickly spread to the suburbs outside the walls (St Giles, Blackheath, Stepney, Saffron Hill, Petticoat Lane).73 These were more secretive, and more furtive, establishments that found a new home in small lower-class alehouses, and in upper-class taverns. But the aristocracy did not forgo the illicit pleasures of water for long; a century later the steam bath reappeared in the luxurious upper-class establishments known as bagnios.

In most respects medieval society was not a ‘dirty’ society—far from it. Alongside intense religiosity, there was intense materialism. Socially speaking, personal freshness actually mattered, and was quite an accomplishment under the circumstances; though perhaps too difficult an accomplishment for many, at least on a regular basis. But the Catholic Church, which as a whole had fought so hard to impose intellectual refinement, physical cleanliness, and sexual cleanness over the centuries, adapting itself to various strategies to win over unwilling populations, suddenly found itself under a bruising attack for its own moral laxities. The Church had unwisely persecuted extreme ascetic Church reformers such as the Albigensian Cathars (Greek kathari, the pure ones); but the ascetic movements refused to die away, and asceticism split the Church once more. A renewed programme of ascetic austerity (and celibacy) was reimposed successfully on all Catholic clergy after the Counter-Reformation Council of Trent in 1562–3, but by then the damage had been done.74 The trend towards decentralized Christianity was irreversible in northern Europe at least, where many Protestant ascetics had come to believe that each sinner held his or her own conscience, and bodily welfare, entirely in his or her own hands.