TO THE PRESENT AND FUTURE AGES, GREETINGS.

… For it is my hope and my desire that [this work] will contribute to the common good; that through it the higher physicians will somewhat raise their thoughts, and not devote all their time to common cures, nor be honoured for necessity only; but that they will become instruments and dispensers of God’s power and mercy in prolonging and renewing the life of man, the rather because it is effected by safe, convenient, and civil, though hitherto unattempted methods. For although we Christians ever arrive and pant after the land of promise, yet meanwhile it will be a mark of God’s favour if in our pilgrimage through the wilderness of this world, these our shoes and garments (I mean our frail bodies) are as little worn out as possible.1

Thus in 1623 Francis Bacon opened his ‘History of Life and Death’, Part III of his famous Instauratio Magna, a rallying cry for the reform of European science. Three hundred years later Europeans would be stripping off their heavy clothes and exposing their naked skin to water, exercise, light, and air, and often living until they were 80, all in the name of prolongevity hygiene—truly a triumph for ‘safe, convenient and civil’ methods. The early modern period starts the final countdown to modernity, c.AD 1500–2007. From now on the scene shifts to northern Europe and the interrelationships between the British Isles, France, and Germany (in particular), and their many long-lasting contributions to the modern European hygienic renaissance; and more especially to the story of English Protestantism, with its enthusiastic adherence to ideologies of health and purity.

Throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the classical discipline of hygiene was the subject of intense speculation and equally intense beliefs, in which humanism played a significant role. The idea of political cleansing or ‘purging’ entered European discourse with a vengeance between 1500 and 1700, brilliantly and viscerally heralded by the ascetic Dutch scholar Desiderius Erasmus (1466–1536), the godfather of humanism. His extraordinary burlesque on the excesses of late medieval life Folly’s Praise of Folly (1511) was an instant hit throughout Europe (with forty-three editions in his lifetime); his next manifesto, Antibarbari (1514), railed against a corrupt Church, and corrupted Church scholars writing corrupted barbaric texts: ‘what disaster it was that had swept away the rich, flourishing, joyful fruits of the finest culture, and why a tragic and terrible deluge had shamefully overwhelmed all the literature of the ancients that used to be so pure’.2 Reform of the Catholic Church was Erasmus’ aim; but the Protestant Reformation in northern Europe became a massive and irreversible social revolution.

In England the break from Rome created a new national identity permeated and defined by both Protestantism and humanism. When Bacon wrote in the 1620s, there was already an army of English Protestant readers and authors ready and willing to accept the Baconian challenge to go out and ‘experiment’ on the natural world. These efforts created a distinctive school of English science and hygiene, which later evolved into a full-blown scientific project. Following the upheavals of the Civil War and the Restoration, a peaceful religious settlement after 1688 gave English scientists a renewed opportunity to cleanse learning and deliver it from the obscure ‘Rubbish of the Schools’. Open experimentation and transparent proof was to provide the new ‘clear gaze’ of natural science—the light that was to illuminate the next century’s Enlightenment. Protestantism itself was thoroughly caught up in the triangular philosophical relationship between Reason, Flesh, and the Soul that we have seen before, in Greece and Late Antiquity—and it was set firmly against the Flesh.3 The Flesh, however, remained naturally of the most immediate concern to most populations, most of the time. Throughout both of these centuries Flesh was privately pampered, and everywhere on display.

The Renaissance continued the love affair with domestic bodily delights begun in the ancient courts and continued throughout the Middle Ages. Between 1500 and 1750 the European population doubled to around 127.5 million, most of this growth occurring before 1625. There was an explosion of ostentatious fine art and architecture as kings, noblemen, and merchant princes spent fortunes in a tidal wave of brick and stone—palaces, town and suburban mansions, with parks furnished with elegant knot gardens, water features, and little pavilions set by lakes. In 1500 only four cities (Paris, Milan, Naples, and Venice) had populations of more than 100,000 inhabitants; by 1700 there were twelve, with London and Paris containing over 500,000 inhabitants.4 Over the next two centuries in Europe, urban fresh-water and riverine sources were extended, and water-carrying became an important service industry; the public fountain (‘conduit’ in English) was the basic and most popular public facility, often equipped with large laundering tanks. But the public pipes were also being tapped by increasing numbers of private pipes; in England the medieval prohibition on private tapping of this scarce communal resource had gradually eroded from the thirteenth century onwards, although generally for privileged persons only.5

By the mid-1500s the grander European palaces were installing plumbed water supplies with full drainage, in the neoclassical style. The built-in bath or grooming suite was a luxury many princes and nobility were eager to acquire, as in Duke Frederico da Montefeltro’s palace at Urbino, which had a fixed stone bath, latrine, and a small reading closet set in an external tower adjoining his large bedroom and public antechambers. Francis I of France had a full suite of baths installed in his ground floor suite, leading out into the garden, at his new palace at Fontainebleau; and there is no doubt that bathtubs held a special place in the sixteenth-century artistic School of Fontainebleau.6 Not to be outdone, Henry VIII of England also built to modern Renaissance standards of convenience at his new palace at Hampton Court, and in renovations at Whitehall and other palaces. At Hampton Court he built an extra tower—the Bayne Tower—with a bath, drop-latrine, and private suite; he also had cold-water cisterns installed on the roof above the upper-level suites to give them piped-water facilities, for fixed stone hand-basins if not fixed baths (though well supplied with the usual portable, upholstered, hooped bathtub). Another of his sanitary innovations at Hampton Court was the Great House of Easement, a four-tier, twenty-eight-seater communal latrine block set over the west arm of the moat. He also laid out two tennis courts, two bowling alleys, and a tilt-yard, having a great humanist passion for sporting exercise.7

Italy was the epicentre of the court life until the rise of Paris in the mid-seventeenth century, and Baldesar Castiglione’s famous etiquette manual The Book of the Courtier (1528) was a courtesie for its time—a new type of Ovidian self-cultivation using classical authors instead of Christian ones, foreshadowing the rise of what historians have called ‘affective individualism’, or a new psychology of ‘intimacy’.8 Elizabeth I of England, educated as a humanist princess, was a perfect exemplar of this new Italian civility (and almost a royal ganika).9 Elizabeth was known to be fussy about her health—she hated being ill. She preserved her health and lived to old age by apparently following a sensible humanist health regimen; she ate and drank abstemiously, took plenty of exercise, and undoubtedly owned a copy of Sir Thomas Elyot’s hugely successful Castel of Helth (1539; five editions by 1560), dedicated to her father’s chief minister Thomas Cromwell. She always travelled with her bed and hip bath, and had bathing facilities in all of her palaces, including a sweat bath—her ‘warm box’ or ‘warm nest’—inherited from her father at Richmond, her favourite palace. At Richmond she also installed a prototype of the water closet, the invention of her godson ‘Boy Jack’, Sir John Harington (translator of the Salerno Regimen). At Whitehall, Elizabeth also had a hot room with a ceramic tiled stove, as well as a large bath and grooming suite, both inherited from her father, in which to spend time with her intimate companions. This suite was effectively her Cabinet of the Morning. It contained her bedroom, and next to it ‘a fine bathroom … [where] the water pours from oyster shells and different kinds of rock’. Next to the bathroom was a room with an organ ‘on which two people can play duets, also a large chest completely covered in silk, and a clock which plays times by striking a bell’. Next to this was a room ‘where the Queen keeps her books’.10 Indeed royal baths were so à la mode that a bathhouse was specially built for Mary, Queen of Scots, at Holyrood Palace in the late 1560s; so there is no reason to think that Queen Elizabeth I did not thoroughly enjoy her monthly bath ‘whether she needed it or no’ (probably at the time of the menses) and was certainly likely to have taken them more often than that, when returning to Richmond or Whitehall after a long cold journey or a dusty ride on a hot afternoon.

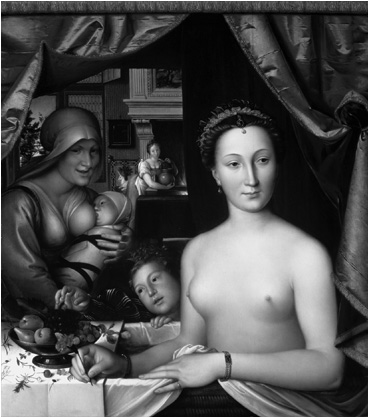

12 The royal courtesan Diane de Poitiers disrobed and relaxing in her bath annexe and living quarters, by the sixteenth-century French court painter François Clouet, of the School of Fontainebleau, where bathing was held in high esteem.

In any case she would have known all about baths, being well versed in the ‘arts of adornment’ and having a passionate interest in Italian cosmetics. The whole edifice of practical therapeutics stood firm during this very late phase of medieval culture. Galenic traditions were firmly built into domestic medicine—as seen especially in early modern descriptions of childbirth, where the mother was supplied with a battery of hot relaxing foods, drinks, washes, and anointments, in a heated chamber, by her family, female neighbours, and friends.11 ‘Social’ grooming affected rich and poor alike. At the lower end of society, the political hierarchy of a village was as complex as any court, and it imposed its own rules and festivities on its participants on all important occasions—at birth, marriage, and death—when grooming would have been lengthy, giving great attention to all the parts (hair, face, hands, feet) and using whatever simple cosmetics could be made, gathered, or borrowed. Daily grooming with basins, combs, and cloths may have been more limited, and was probably non-existent among vagrants or the lowest ranks of the ‘shame-faced poor’ (except for the most ancient basic manual actions); but family sickness would have been the time when such old cosmetic and herbal skills of ‘kitchen physik’ as the household had were brought into play. The symbolic division between long periods of work and short periods of play was marked by the now near-universal habit of having (wherever possible, and certainly among the godly) two sets of clothing: dirty work clothing, and Sunday or festive best.

But it was the luxury trades that set the pace of popular consumerism, and aristocratic fashions were again the driving force in creating markets. At the beginning of Elizabeth’s reign in 1558, the Venetian ambassador noted the court ladies’ ‘fresh’ complexions and general lack of paint, at a time when Venetian beauty boxes were large and elaborate affairs, with waters, paints, patches, and ‘even preparations for tinting the teeth and eyelids’. Fifty years later the whole of the English court and aristocracy were ‘very Italianate’ and cosmetics-mad, with paints, beauty patches, wigs (blonde and henna-auburn), and bejewelled hair. The trade of the barbers themselves was now situated well beyond the professional ramparts; but despite this the barbers and apothecaries were doing a flourishing trade in this period, servicing a needy population from their small street shops. Down at street level, customers were not looking for moral judgements, but were involved in a more ‘desperate or cynical search for the means of personal definition and social acceptability’. In London generally, it was ‘a rare face if it be not painted’, according to one satirical broadside:

Waters she hath to make her face to shine,

Confections, eke, to clarify her skin;

Lip salve and cloths of a rich scarlet dye …

Ointment, wherewith she sprinkles oe’r her face,

And lustrifies her beauty’s dying grace…

Storax and spikenard, she burns in her chamber,

And daubs herself with civet, musk, and amber.12

More careful skin care went into the later sixteenth-century fashion for low-cut necklines, and even bared breasts, a throwback to the fashions of the late fifteenth century: ‘Your garments must be so worne always, that your white pappes may be seene …’. But male fashion was equally sensuous. Young Elizabethan courtiers were peacocking dandies like their medieval counterparts; the courtly English ‘Cavalier’ of the seventeenth century (albeit often armed for battle) has been described as an ‘ornament of conversation, personal beauty and erotic attraction’, and his loose flowing locks mirrored the curls and tresses of the courtly women.13 Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century European male and female fashions were ornamented with ribbons and lace and garnished with quantities of important accessories such as fans, pomanders, gloves, and handkerchiefs. These fashion accessories were all objects of refinement (like forks): they defended the user against external dirt. Gloves kept the hands white, clean, and soft, handkerchiefs wiped away dirt; fans and pomanders wafted away bad air. (Interestingly, some of these accessories also defended against extremes of heat and cold; another refinement—or retraining—of the senses.)

Fortunes were made by barbers, apothecaries, wig-makers, perfumiers, clothiers, and stay-makers—and soap-boilers. High-quality hard-soap imports began to rise steadily in England from the late sixteenth century, and increasingly wealthy local manufacturers such as the London wholesaler Henry Bradstreet manufactured perfumed toilet soaps as well as soft soap for clothes and household cleaning. By 1643 English soap production and consumption had risen so steadily that soap was designated one of the eight staple domestic ‘necessities’ (namely, soap, beer, spirits, cloth, salt, glass, leather, and candles) that were to be taxed under a new Commonwealth Excise system borrowed from the Dutch Republic; this marked the start of an extensive and long-running ‘black market’ soap-smuggling trade between England and the northern coast of France.14

Linen was the hallmark of the courtier and the man of distinction: ‘It is enough if he always has fine linen, and very white.’ According to the historian Georges Vigarello, a daily change of shirt had become normal for men in French court circles by the late sixteenth century, while French probate inventories show a steep rise in numbers of gentlemen’s shirts (up to an average of thirty) by the end of the seventeenth century. French court correspondence from women in the seventeenth century show an almost nunlike attention to clean linen, and the word ‘clean’ (propre) became a significant term of praise: Mme de Maintenon had a ‘noble and clean’ appearance; Mme de Contie had ‘extreme cleanliness’; Mme Seguier ‘was never beautiful, but she was clean’ (the modest epitaph of many a gentlewoman for centuries to come).

White underlinen displayed every trace of dirt, absorbed the waste juices from the pores, protected the skin, and was increasingly seen as a cleansing agent in its own right. So far had the theory of underlinen progressed by 1626 that a fashionable French architect could confidently denounce the necessity for building domestic baths: ‘We can more easily do without them than the ancients, because of our use of linen, which today serves to keep the body clean, more conveniently than could the steam-baths and baths of the ancients, who were denied the use and convenience of linen.’15 This was to some extent a self-fulfilling prophecy, as French architects stopped building the old palatial appartements de bains in towers, but replaced them by much smaller and more intimate cabinets de bains next to the bedchamber.16 Two marble-built bath suites went into Louis XIV’s own and his mistress’s chambers at Versailles, and six cabinets de bains were built in other bedroom suites; but Louis did not like bathing, and rarely took one: ‘The King was never pleased to become accustomed to bathing in his chamber.’ On the other hand, he was kept perfectly clean by his attendants, who continually rubbed him down with scented linen cloths, changed sweaty shirts at night, and changed his complete costume two or three times a day at least—‘the consequence of the king’s love of comfort, and fear of being uncomfortable’.17

It is worth noting, however, in comparison to all this courtly daintiness, that for much of the population, one or two rough hemp (rather than soft linen) undershirts or shifts were enough to get by with, for bare necessity. But the peasant economy was also expanding. Linen wares sold by pedlars and packmen to English rural farming households showed a steady rise ‘from at least the 1680s’; while the French and German peasantry, too, were beginning to accumulate household linen (if not much underwear) for their marriage trousseaus. Linen was a major European commodity, and new cloth industries such as lacemaking, or weaving fustian (a new linen-wool mix) brought vital work to many villages, as well as cloth for their backs. But it was the people in the towns who bought most of the mercer’s wares.18

Compared to Paris, Venice, or Florence, up until the sixteenth century London had been a European cultural backwater; all this was to change over the next hundred years, during the course of the English Reformation, as London slowly became a major European port—especially after the East India Company was founded in 1600. Money talked to money, and the City and the court literally grew towards each other along the north bank of the Thames; both joined in grief when the London Stock Exchange burned down in the Great Fire of London in 1666 (it was quickly rebuilt on an even larger and grander scale). The English population was roughly 3 million in 1541, and 5 million by 1700. As trade and manufacturing grew, the rural population flocked to a new life in the market towns, provincial capitals, and above all London, an upwardly mobile emigration which sharpened their ‘horizontal’ sense of rank and respectability while increasing the social distance they set between themselves and the poor—an ongoing ‘civilizing process’ now extending into the middle ranks.19 In late seventeenth-century London the middling classes formed an estimated 25 per cent of the population—less than half of the 70 per cent of the labouring classes, but far more numerous than the 5 per cent of the nobility; and far more numerous than in any rural parish. The elite squires, doctors, lawyers, or merchants at the top of their trade—the ‘plums’ (those earning over £10,000 a year)—had everything that money could buy. In their new tall urban houses they had spacious saloons for public display and private parlours for conversation, while the old bedroom-cum-meeting-place was transferred upstairs to new private suites of bed and dressing chambers. But the majority of the English middling classes were not rich. As the decades went by they could increasingly afford little luxuries here and there—a new clock, a piece of new furniture, a few books, more clothes, white bread instead of brown, candles instead of oil, bought soap instead of homemade. ‘An income of £50 was some three, four, or even five times the annual income of a labourer, and would allow a family to eat well, employ a servant and live comfortably.’20

The real social stresses occurred towards the bottom of the social scale, where any population increase battled with scarce local resources, seasonal employment, and subsistence wages—all traditional causes of peasant revolt and urban disorder. It was in these groups that radical English Protestantism took deep root and later supplied the muscle and the democratic fervour of the Commonwealth Revolution. But the real revolution among the English middling classes had already occurred when John Wyclif (1329–84) translated the Bible into vernacular English for the common reader, opening up all the endless possibilities of the Word.21 Wyclif’s English followers, the Lollards, were early precursors of the flood of religious protestation in Europe that led to Calvin in Geneva, Zwingli in Zurich, and the Lutherans in Saxony; and eventually to a solidly Protestant ‘rim’ emerging around the North Sea—in Scandinavia, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, England, and Scotland—which later extended across the North Atlantic to the east coast of North America.22 The map of Protestantism within the British Isles shows reform and radicalism strong among the lower-middle classes in towns and semi-industrial rural areas, among independent craftsmen, textile workers, smallholders, and provincial retailers. They found a secure footing at local level, forming small cells of local Saints, congregations, magistrates, and preaching ministers. They took their new ‘seriousness’ into all walks of professional life, including law, medicine, trade, and the universities; in London they inhabited the coffee-houses, scoured the newspapers, and formed the bedrock of a new breed of industrious civil servants (of whom Samuel Pepys was one).23

English Protestant puritans led a fierce spiritual and intellectual life. Above all (and this was a strong appeal for migrant families who had left old social ties behind them) their religion promised an entirely new start: ‘New minds, new memories, new judgements, new affects… new love, new joy… new food, new raiment, new language, new company… new ends and aims… [This is] the Excellence, Amiableness, Comfort and Content which is to be found in the ways of Purity and Holiness.’24 Yet again there were profound historical consequences from the revival of asceticism, especially one that was noted long ago in the monasteries, and which had worked well for the Catholic Church: if you worked hard and lived soberly, you were almost bound to accumulate money. You could also give that money away, in good works. Money obviously had its attractions for fellow-travellers, backsliders, and the disillusioned; but for the moment, English puritan movements relished their attacks on filthy Lucre and the privileges of the rich, in their attempt to capture and purify society and the state.

They also embraced the healing mission. The democratic political content of the early Protestant health message was a particularly powerful one: God made everyone equal, and the means of cure were apparently open to all. This message liberated individuals, and put the care of their health firmly in their own hands. Many English sectarians were staunch popular empiricists who (like Gerrard Winstanley) asserted the moral right to judge the world and see things ‘by the material eyes of this flesh’; and also, increasingly, the right to experiment on their own bodies.

The renewed sixteenth- and seventeenth-century plague outbreaks, unlike syphilis, struck the innocents of all classes and terrified everyone equally. They concentrated everybody’s mind on self-help and self-preservation. Daniel Defoe later described the ravaged silence of empty London streets, with green grass growing between the cobbles outside, and people locked indoors living quietly and soberly like himself, sticking rigidly to all the health instructions they could find. In the early days of an attack the quacks were out in force selling magical elixirs, amulets, charms, potions, pamphlets, and broadsides, but public disillusion soon set in.25 The deeply rooted belief in internal potions and purges continued, but as the severity of the plague visitations increased, there must have been many people who heard recommendations on regimen, or opened a printed advice book or pamphlet for the first time during an epidemic, and thereafter found a way to order not only their health, but their whole life: ‘This boke techyng al people to governe them in helthe… is as profitable as needeful to be had … ‘ announced the title page of the printed Regimen Sanitatis Salerni, translated by Thomas Paynell (first edition 1528; five more editions by 1617). The very first printed English medical advice book, The Gouernayle [Governor] of Helthe, was taken from an older manuscript and published by William Caxton in 1489. The early printed medical advice market in England was not large (possibly 3 per cent of all titles, reaching roughly one in twenty book owners), but it grew steadily and was mostly in readable English; the number of English medical works actually published in Latin between c.1500 and 1640, remarks one historian, ‘was paltry’.26 Thomas Phayre’s The Book of Children (1544), Thomas Moulton’s The Myrrour or Glasse of Helth (1545), and Andrew Boorde’s Compendious Regiment or a Dyetary of Helth (1562), to name but a few, were sold alongside the growing numbers of do-it-yourself herbals, almanacs, receipt books, and surgical manuals.

Many early small books and pamphlets for poor, defenceless, and suffering households were written out of Christian charity and fellow feeling. Charitable Protestant authors found themselves not only grappling with ‘barbarous’ medical terminology, but having to defend themselves against their abuse of medical privileges—laying open all those craft ‘secrets’ and breaking the conventional monopolies of medical knowledge. It was a difficult task they managed with some aplomb, as in Humphrey Lloyd’s The Treasuri of Helth contayning Many Profitable Medicines (c.1556):

[I do not do this] to maintayne thru filthy lucre and blind boldness … but …I hold that it should be for the use and profyte of such honeste persons as might modestly and discreetly (either in tyme of necessitye when no lerned physicion is at hande, or els conferring wyth some lerned man and usynge hys councel) mynister the thynges herein conteyned to go about the practyse thereof, and upon these most honest and godly consideracions, I take upon me this heavy burthen and hard province… [Do not] despise this symple work because it is not garnished wyth colours of rhetoricke and fine polished termes, but rather consider that physicke is an arte certaine only to be plainly and distinctly taught… Wherefore I, trusting to the sincere and indifferent judgement of the reader, do entirely desire him to pray wyth me and to him that created the physicks of the earth, and commended that we should honour the Physician, to preserve this Realme of England in most prosperous and contiynuall health, and to endow the inhabitants thereof, with perfect understanding and the most desired knowledge of his holy word. Amen.27

Temperance and moderation—‘how to govern and preserve thyself’—were godly virtues that came into their own in these desperate times, and was popularly known as ‘the Sober Life’. The increased emphasis on the absolutely correct balance of the bodily humours, and a greater emphasis on the environmental rules of the non-naturals (newly rediscovered from the Greek texts), suggest that full hygienic regimen was considered to be the latest, most modern, weapon against the plague. The doctors were unswerving in their recommendation of hygienic temperance and moderation during plague outbreaks—the body should not be pushed to any extremes whatsoever: ‘[neither] all manner of excess and outrage of meat and drink …no hot foods …no lechery…Also use no baths or stoves; nor swet not too much, for all openeth the pores of a manne’s body and maketh the venemous ayre to enter and for to infecte the bloude …’.28 Covering up and keeping clean in every other way but that was considered safer. The plague regimens were insistent on clean streets and clean rooms, fresh air and sweet odours, a sober diet, good grooming and clean skin, and well-kept clothing.

Many English authors embraced the idea of a reformed ‘humane’ classical medicine with enthusiasm, and Thomas Elyot’s Castel of Helth was their benchmark for over a century. His conversational prose was modelled on Celsus (whom he cites constantly) and Galen’s De Sanitate Tuenda, ‘newly translated’ from corrupted texts. In the true style of humanist intimacy he pours out his autobiography onto the page, to explain why he ‘is become a physician, and writeth in publick, which beseemeth not a knight, he mought have been much better occupied’, and then describing his four-year health crisis (his diacrasie) in detail, concluding he had been ‘long in error’ with an over-hot Galenic regimen—‘wherefore first I did throw away my quilted cappe, & my other close bonnets, & only did lye in a thinne capes, which I have after used both winter and summer’.29 In Elyot each section on the six ‘Thynges not Natural’ is carefully laid out according to the correct complexions, seasons, diet, and evacuations—but with a scattering of new moral prohibitions. The artificial evacuations, for example (vomit, letting of blood, scarifying or cupping, and purging) are dealt with at length; whereas the natural evacuations (sweating, provocation of urine, spitting, and ‘naturall purgations’—the bowels, the menses) are considered too shameful to mention: ‘I do purposely omit to write of them in this place, for as much as in this realme it has been accompted not honest, to declare them in the vulgar tongue, but only secretly.’ Baths are briefly mentioned, as a good evacuation, but only if they are temperate; whereas exercise is enthused about at length—exercise ‘for them that desire to remayne long in helthe, is most diligently, and as I must say, most scrupulously to be observed’.

Exercise was to become a strong ‘localized’ feature of English hygienic regimen over the next few centuries, in part because the customary sports and older Church festivities (known as ‘Church ales’) had been early targets for sober ascetic reformers—‘some Puritaines and precise people’, as King James I described them. Humanist princes had augmented their hunting and dancing with new courtly sports, such as indoor tennis and outdoor bowling, which could be played in their new pleasure parks, and Everard Digby’s famous manual and treatise on swimming, De Arte Natande, was published in 1587.30 Elyot’s exercise regimen was taken directly from the Greek texts—including even some of the old Methodist ‘passive’ exercise therapies such as being carried by chair, sitting in a boat or barge, or riding on an ambling horse. In the morning there should if possible be vigorous rubbing of the limbs and loud ‘vociferous’ singing; and in the afternoon, outdoor games and sports.31 The popular sporting revival of the sixteenth century was only temporarily crushed by Commonwealth decree in the mid-seventeenth century, and was enthusiastically revived after the Restoration.

One major effect of the humanist neoclassical hygiene revival was the spur it gave to empirical experimentation—and the widespread publicity these efforts now received through mass printing. The first and most famous European experimenter in hygienic health care was Luigi Cornaro, whose Discorsi della Vita Sobria (‘Discourses on the Sober Life’, 1558) seemed to provide proof that a disciplined regimen actually worked. The Discourses were published in sections over a number of years, translated into many European languages, and were effectively health diaries describing Cornaro’s many years of moderate diet and simple regimen, up to the age of 83. A eulogy of Cornaro translated into English in a work entitled Hygiasticon: or, The Right Cause of Preserving Life and Health unto Extream Old Age (1636)—an early and rare use of the Greek word ‘hygiene’ in English—described

a sober Life or diet, [as that] which sets stint not only in drink but also in meat; so that a man must neither eat not drink any more, than the constitution of his bodie allows, with reference to the services of his mind … It expells diseases, preserves the body agil, healthful, pure and clean from noysomeness and filthinesse, causeth long life, breeds quiet sleep, makes ordinary fare equall in sweetness to the greatest dainties and moreover keeps the senses sound, and the memories fresh, quiets the passions, drives away Wrath and Melancholie, and breaks the fire of Lust; in a word, replenesheth both soul and body with exceeding good things, so that it may well be termed, the mother of Health, of cheerfulnesse, of Wisdom, and in summe, of all Vertues …32

The self-experiments of Cornaro were the inspiration for another landmark hygienist author, the early seventeenth-century Italian experimenter and friend of Galileo, Sanctorius Sanctorius (1561–1636), whose deeply mathematical and atomistic work Medicina Statica (1614) was an early contribution to iatro-mechanism in European physiology. In the cause of purified classicism, Sanctorius set out to revive the neglected philosophy of Asclepiades, in particular the mechanical Methodist theory of strictum et laxum— the relaxing or tightening of the atoms, corpuscles, pores, or ducts—which was also attracting interest in other quarters. Sanctorius tested the Sober Diet by gradually reducing his food (and his excrement) to exact and minute portions, and then weighing himself daily in his famous ‘balance chair’ (always illustrated on the frontispiece).33 By measuring the shortfall between his intake and outgo, Sanctorius thought he had experimentally exposed the action of something classical authors had called the ‘insensible perspiration’, an involuntary evacuation which apparently wafted waste products away through the pores of the skin; and thus he concluded that it was vital that the pores were not closed up or ‘obstructed’, in order to let the poisonous waste matter vaporize freely. This was certainly modern mechanical science to seventeenth-century eyes, and set off a popular craze for weighing and measuring one’s own body—forerunner to the precise ‘weight-watching’ regimes of the modern slimming diet. Thanks to Sanctorius, the doctrine of cleansing ‘insensible perspiration’ became one of the earliest popularly known hard facts of the physiological sciences, and did not lose its persuasive hold on the European public mind until the late nineteenth century; in the eighteenth century it played a particularly large part in all hygienic rhetoric.34

13 The weighing-scales, or balance-chair, from Sanctorius’ Medicina Statica (1614).

In 1553 yet another trickle of humanist medical thought joined the main flow when a Venetian publisher, Thomas Junta, took it upon himself to compile a definitive description of all the major European mineral and thermal waters, De Balneis Omnia (1553), which primed yet another revival of European mineral-water balneology.35 Disciples of the iconoclastic Protestant chemist Paracelsus (1493–1542) turned up at mineral springs everywhere, with all their equipment, eagerly checking the mineral content and its supposed effects, carrying on the classification process started by the Romans. The doctors were given a professional springboard via Paracelsian chemistry, and their enthusiasm transmitted itself both to their clients and to baths builders. The English medical author Dr William Turner visited Italy, translated Junta, and produced England’s first spa guide, A Book of the Natures and properties as well as of the Bathes in England as of Other Bathes in Germanye and Italye—very necessary for all those persons that can not be healed without the help of natural bathes (1562, 1568). As the Anglican dean of Wells Cathedral, he devoutly deplored the still-prevalent custom of mixed bathing, and still more the lack of Christian charity towards ‘the poure sicke and diseased people that resort thither… There is money enough spent upon cockfightings, tennys playces, parkes, banquetings, pageants, plays … but I have not heard tell of a rich man hath spent upon these notable Bathes… one grote in [many] years.’36 He carefully gave directions for cheap and homely domestic medical baths—‘certayne rules how that everye man maye make artificiall bathes at home’—with the learned physician supplying the correct brimstone, alum, saltpetre, salt, or copper according to the disease of his patient.

But the new mineral waters were mostly taken internally, as a purge. ‘Spa’ became the generic word for a new crop of lesser cold mineral springs, after the success of the fashionable late sixteenth-century water resort at Spa in the Ardennes. European spa illustrations from the seventeenth century show stone-built neoclassical-style town squares, with richly and fully clad figures gathered around tall fountains and basins with cups in their hands, testifying to the new craze for drinking the water. The three main categories of chalybeate, sulphurous, and saline (‘tart, stinking, and salt’) were used as diuretics to ‘provoke’ the evacuation of very large quantities of stools and urine—‘as Soap put to Foul Linnen with Water Pirgeth and Cleanseth all Filth and maketh them to become White again; so these Waters with their Saponary and Detersive Quality clean well the whole Microcosm or Body of Man from all Feculency and Impurities’.37

Exposing the external skin to watery ablution and purification, however, was quite another matter. In Germany the period of hot-bath decline coincided with a rise of increasingly hysterical river-bathing regulations, suggesting that artisanal, merchant, and courtly youth had taken to brothels and cold river-bathing—naked bathing—the old German custom from pre-bathhouse days; while in France, river-bathing became not only popular but fashionable at court.38 As far as hot water is concerned, there is (so far) little evidence of small local artisanal stews or public baths ever existing, in England, to the same extent as in other parts of Europe. For the wealthy few in seventeenth-century London there were private ‘bagnios’ based on Italian models, but also owing much to the influence of the Turkish ‘hummums’ imported into Europe from the flourishing Turkish Empire. These later bagnios were discreet private club-like establishments serving an exclusive (usually aristocratic) male and female clientele.39 We have a rare description of a real but rather special English Royal Bagnio at Charing Cross, London, built into the back of the palace gardens in Charles II’s reign, which in 1795 was still a substantial brick-built complex, with a ‘large and noble cold bath’, sweating rooms, and a suite of upstairs entertaining rooms, with columns, mouldings, and wide staircases, all guarded by a ‘massive gate nearly four inches thick [with] a strong iron grating, and in the middle of it a very small iron grating as all such houses had to peep through’.40 Samuel Pepys’s wife famously went once to some public baths ‘intending to be very clean’ and then reportedly never went again—was she scared of getting into deep water?

In seventeenth-century London public baths were evidently deeply mistrusted. When Dr Peter Chamberlen attempted to open a set of ‘Publick Artificiall Baths and Bath-Stoves’ in London in 1648, similar to those in ‘Germany, Poland, Denmark and Muscovia’, and arguing that public hot baths could ‘save above 10,000 lives a year’, he was firmly rebuffed. The Civil War Parliamentary Committee told him that his baths would be ‘hurtful to the Commonwealth’ since it was well known that public baths had often been the cause of ‘much Physical Prejudice, effeminating bodies and procuring infirmities, and morall in debauching the manners of the people’. There were already enough ‘divers Cradles, Tubbs, Boxes, Chairs, Baths and bath-stoves’ in private houses.41 In their eyes, the plague and pox had taught everyone to be vigilant about their health, and to stay sober and clean in every way. Public baths were no longer necessary. The godly could clean themselves at home. The hot bath represented the bad old days and ways, and in England moral prejudice against hot baths continued well into the nineteenth century.

Each Reformed body was the temple of the soul, kept pure by the familiar practices of asceticism: diet, dress, voice, gait, demeanour, and religious duties. Ascetic doctrines effectively threw a cordon between the true Saints and the rest of the population, so that even the houses of the ungodly were like ‘so many filthy cages of unclean Birds, so many styes of all manner of abominations’.42 Protestant housewifery reached its culmination in Geneva, and particularly in the Netherlands, where even the streets were swept and washed, and domestic manuals were proudly decorated with symbolic brooms and mops; Dutch artists also painted tender scenes of domestic nitpicking, unequalled before or since. The English Protestant housewifery genre, by comparison, was discreetly vague and ladylike, composed mainly of recipes, and largely untouched by Calvinist household cleansing propaganda.43

The ascetic discipline was underlined by an austere dress code and a perfectly clean and neat appearance, described by Bacon as ‘a civil cleanliness ever esteemed to proceed from a due reverence to God, to society, and to ourselves’. Erasmus had put his faith in early training in his influential humanist educational handbook On Civility in Children (1532); and the Czech Protestant Comenius’ School of Infancy (1633) likewise instructed parents to teach temperance, cleanliness, and decorum from the very beginning of life:

Immediately, in the first year, the foundations of cleanliness may be laid, by nursing the infant in as cleanly and neat a way as possible, which the bearers ought to know how to do, if they are not destitute of sense. In the second, third, and following years it is proper to teach children to take their food decorously, not to soil their fingers with fat, and not, by scattering their food, to stain themselves … Similar cleanliness and neatness may be exacted in their dress; not to sweep the ground with their clothes, and not designedly to stain and soil them; which is usual in children by reason of their want of providence; and yet parents, through a remarkable supineness, connive at such things.44

The low-cut medieval gown disappeared very early in some European Protestant areas; in some northern German towns it was ordered that no female citizen could go around with a neckline any lower than the width of one finger below the collarbone. Plainer and purer Protestant sectarians had real moral objections to colour and pattern: ‘Washing our garments to keep them sweet is cleanly, but it is the opposite to real cleanliness to hide dirt in them … Real cleanliness becometh a holy people; but hiding that which is not clean by colouring our garments seems contrary to the sweetness of sincerity.’ Black and white became the dress code of Reformed asceticism; but where buttoning up was required, fine linen compensated. Sober black cloth had long been favoured by the clerically minded Catholic Spanish court; and the wealthy Dutch Protestant bourgeoisie who favoured the clerical style have since become famous through their portraiture—all rustling black silk, dark velvet, and covered-up modesty, strikingly set off by magnificent lace and linen cuffs, collars, and caps.45

There were no regular lustral baths to perform in Protestantism, but the act of washing was self-consciously symbolic, metaphysical, and erudite. Baptism was a key theme. Edward Topsell admonished the faithful to ‘the outward cleansing and washing away of the filth of our bodies, being the saviour of sinne raigning in us’.46 The zealous puritan Philip Stubbes urged washing because ‘as the filthinesse and pollution of my bodie is washed and made clean by the element of water; so is my bodie and soule purified and washed from the spots and blemishes of sin, by the precious blood of Jesus Christ… This washing putteth me in rememberance of my baptism.’ The metaphysical Protestant poet George Herbert wrote that on Sunday especially:

Affect in all things about thee cleanliness,

Let thy minde’s sweetness have his operation

Upon thy body, clothes and habitation…

That all may gladly boarde thee, as a flowre…47

At a somewhat less exalted social level, the surgeon William Bullein seems to have found it necessary to defend and promote washing (but only with cold water) and put an unusually full and earnest section on cleanly grooming into the morning regimen of his small handbook The Government of Health (1558), aimed at the student or the busy man of affairs about town:

Plaine people in the countrie, as carters, threshers, ditchers, colliers, and plowmen, use seldom times to wash their hands, as appeareth by their filthynes, and verie few times combe their heads, as is seen by floxes, nittes, grease, feathers, straw, and such like, which hangeth in their haires. Whether is washing or combing things to decorate or garnish the body, or else to bring health to the same?

Thou seest that the deere, horse, or cow, will use friction or rubbing themselves against trees both for their ease and health. Birdes and hawkes, after their bathing will prune and rowse themselves upon their branches and perches, and all for health. What should man do, which is reasonable but to keep himself cleane, and often to wash the handes, which is a thyng most comfortable… If it be done often, the hands be also the instruments to the mouth and the eies, with many other thinges commonly to serve the bodie… Kembing of the head is good in the mornings, and doth comfort memories, it is evil at night and openeth the pores. The cutting of toes, haire, and the paring of nailes, cleane keeping of eares, and teeth, be not only things comely and honest, but also holesome rules of Physicke for the superfluous things of the excrements.48

The English Puritans were no ragged dusty ascetic hermits, nor were they sleek priests. They often kept their beards, in imitation of the Jewish prophets; but they despised ornamental (long) hairstyles and were ostentatiously short-haired (or round-headed): ‘Off with those deformed locks, those badges of pride and vanity which you have been so warned of…hate not to be reformed [and] become your Barber, as he has been to some amongst us…’.49 In Comenius’ catechism, baths were approved to ‘wash off sluttishnesse and filth …[and] cleanse and scour away all dustinesse, sweat and foulness’, but any other artificial cosmetics—curled hair, wigs, or perfume—were entirely banished. In the Calvinist world, sexual uncleanness was far more important than mere bodily cleanliness, and English anti-cosmetic tirades were worthy of the Church Fathers themselves, and were highly biblical. ‘Plain Man’ Arthur Dent was no doubt one of many puritan masters of their households who tended to quote Isaiah:

And what say you of our artificial women, which will be better than God made them? They like not his handiwork, they will rend it, and have other complexions, other faces, other hair, other bones, other breasts, and other bellies than God made them … But they will humbled by the Lord … instead of sweet savours there shall be a stink, and instead of a girdle, a rent, and instead of dyeing the hair, baldness …50

Other English puritans were even more foul-mouthed about cosmetic waters and unctions ‘wherewith they besmear their faces’, musk perfume ‘stinkyng before the face of God’, linen starch for ruffs—‘the Devil’s liquor’—and earrings ‘for which they are not ashamed to make holes in their ears’.51

It might seem as if Puritans had abandoned the sensuous body altogether by treating it largely as an asexual object in which all lusts and vanities could be controlled; but this was not entirely so. Many had a surprisingly primitive passion for the God of nature, and his natural works.52 The European Protestant sects who did not accept the spiritual and theological authority of Lutheran Calvinism (notably the Anabaptists, Baptists, Diggers, Seekers, Ranters, Quakers, Pietists, Adamites, the Family of Love, and many others) were idealists who refused to accept the doctrine that the Christian soul was predestined to be sinful at birth: they valued individual experience, questioned the Scriptures as they saw fit, disagreed with infant baptism, and tended to be more millenarian or utopian, believing in the ‘simple plainheartedness or innocency’ of the human soul before the Fall of Adam and Eve, and in the redemptive virtues of Love and communal brotherhood. The radical democrat leader of the English Diggers’ sect, Winstanley, insisted that the supposedly heavenly Age of the Spirit existed, now, in all people:

We may see Adam every day before our eyes walking up and down the street… This innocency or plain-heartedness in man was not an estate 6,000 years ago only, but every branch of mankind passes through it…. Oh ye hearsay preachers, deceive not the people any longer by telling them that this glory shall not be known and seen till the body is laid in the dust. I tell you, this great mystery has begun to appear, and it must be seen by the material eyes of this flesh…53

It was a fight over the soul and the body with some unexpected consequences for the later history of hygiene—the development of Christian naturism (if we can call it that). If he or she wanted, a pure-spirited Adam or Eve could even go naked, testifying their innocence, ‘and live above sin and shame’. According to the historian Christopher Hill, there were many recorded occasions ‘on which very respectable Quakers “went naked for a sign”, with only a loin-cloth about their middles for decency…. In 1652 a lady stripped naked during a church service [in the chapel at Whitehall], crying “Welcome the resurrection!”… such occurrences were less rare at Ranter and Quaker weddings.’54

As Hill discovered, many English sectarians systematically proclaimed the right of natural man to live naturally, and to worship the God of nature; and nothing shows this more than the passionate debates over the hygiene and morality of pure food, cool air, and cold water. Confirming a general moralthermal shift that seems to have begun in the later sixteenth century, English sectarians joined in the general Protestant attack on medieval (Catholic) Galenism, and loudly repudiated the old so-called ‘Hot Regimen’ in favour of a new and ascetic ‘Cold Regimen’.

Diet had long been linked to catharsis and purgation, and easily became a locus for puritanism. The seventeenth century was the time when many (if not most) of the Western world’s ‘Rich Restoratives’ were introduced via the flourishing international trade routes. These new food drugs were cane sugar, tea, coffee, chocolate, and tobacco, and the new drinks made from the chemist’s recent discovery of pure ‘neat’ alcohol—brandy, gin, fortified wines such as port or sherry, and herbal and fruit liqueurs such as aquavit and cherry brandy. All these items went down extremely well with the public, but were regarded by ascetics as excessively corrupting foods that produced overheated brains and venal ‘Hot, fantastick passions of love’. One seventeenth-century English physiologist’s internalized moral hatred of the supine, sickly, effeminate, and above all Foreign ‘Hot Regimen from Hot Climates’ had very clear targets:

Brandy, spirits, strong wines, smoking Tobacco, Hot Baths, wearing flannel and many clothes, keeping in the House, warming of beds, sitting by great fires, drinking continually of Tea and Coffee, want of due exercise of body, by too much study or passion of the mind, by marrying too young, or by too much Venery (which injures Eyes, Digestion, Perspiration, and breeds Winds and Crudities): and for all the effeminacy, Niceness, and weakness of spirits that is produced in the Hysterical and Hypochondriacal…55

Uncompromising temperance and vegetarianism became the badge of English radicalism in the seventeenth century. Pure food or ‘vegetable’ beliefs either came through individual revelation or (increasingly as time wore on) through intellectual persuasion and reference to the natural ‘common sense’ of ‘our forefathers’—‘yea the most of them fed upon graine, corne, roots, pulse, hearbes, weedes and such other baggage, and yet lived longer than wee, were healthfuller than wee’. The ascetic works of classical Pythagoreanism and Indian Vedic vegetarianism were beginning to be rediscovered and admired. The Familists and Adamites had vegetarian followers, mirroring the sects and believers in Cromwell’s Model Army who thought meat-eating unlawful, and cold-water drinkers who abstained from alcohol.56 The famous radical Protestant hermit Roger Crab, after a near-death experience while soldiering during the Civil War, conducted the experiment of living alone on ‘a smalle Roode of ground… at Ickham near Uxbridge… in obedience to the command of Christ’, wearing sackcloth and eating nothing but garden produce:

if naturall Adam had kept to his single naturall fruits of God’s appearance, namely fruits and herbs, we had not been corrupted. Thus we see that by eating and drinking we are swallowed up in corruption… [and] the flesh-destroying Spirits and Angels draweth near us…

By praying, fasting, and suffering the pangs given to him by his ‘Old Man’ (his body), Crab became something of a celebrity healer, preaching against meat and alcohol:

if my patients were any of them wounded or feaverish, I sayd, eating flesh or drinking strong beer would inflame the blood, venom their wounds, and encrease their disease, so there is no proof like experience: so the eating of flesh is an absolute enemy to pure nature; pure nature being the workmanship of a pure God, and corrupt nature under the custody of the devil.57

Fasting was a particular sign of grace. There were many Protestant women who also felt the call of personal prophecy, and embarked on a severe ascetic regime of virginal celibacy, isolation, and, above all, fasting. Anne Wentworth embraced virginity and public preaching; Martha Taylor carried out a ‘Prodigious Abstinence occasioned by twelve months fasting’ and was exhibited publicly in her home; the prophet Sarah Wight starved herself as a penance, lost her sight and hearing, went into a catatonic state, and spoke ‘extempore in soliliquies’.58 Oxford and Cambridge universities were monastic and celibate institutions steeped in the traditions of fasting and the philosophical or ‘Mean Diet’. Protestant Cambridge was the centre of a core group of ascetic Protestant natural philosophers later known as the Neoplatonists, who strenuously opposed the ‘clockwork’ mechanism of Descartes, and argued for the material existence of a transcendent spirit world (including angels): ‘The Platonists doe chiefly take notice of Three kindes of Vehicles, Aetherial, Aerial, and Terrestrial, in every one whereof there may be several degrees of purity and impurity… ‘. Platonism and Pythagoreanism were closely aligned in Cambridge; one leading member of the Neoplatonists, Henry More, was known to be a strict vegetarian who considered it his bodily duty to ‘endeavour after the Highest Purity’.59

In the later seventeenth century, however, the main living prophet of English vegetarianism was the self-taught shepherd, hatter, and popular author Thomas Tryon (1634–1703), who wrote dozens of books on Cleanness and Innocency for all occasions:

There is no other way to obtain the great mystery and Knowledge of God, his Law, and our Selves, but by Self-Denial, Cleanness, Temperance, and Sobriety; in Words, Imployments, Meats and Drinks; all which… [keep] our bodies in Health, and our minds in serenity; rendering us unpolluted Temples, for the Holy Spirit of God to communicate with.60

Condemning all hot ‘Gluttenous and intoxicating Liquors [and] fumes as those of Tobacco, Opium, and the like Poysons’, he followed Crab and preached an Adamite, hermetic, country life, living on vegetables, grains, pulses, and cold water: ‘he that lives as he ought needs but a few things, and those easie to be procured, a small cottage, a little Garden, a Spade, Corn, and Water, white garments, a little wood, a straw-bed, will support Nature to the highest degree’.61 His Pythagorean philosophy led him to abhor the violence and pollution of towns, with their noise, smoke, and nauseous trades (including butchery), and to become a pacifist. In Pythagoras his Mystick Philosophy Reviv’d (1691), Tryon explained that this primarily meant living without killing anything:

Let none of your food be attended with the groans of the innocent Creatures… endeavour and with equal constancy and earnestness to pursue after purity…to eschew things derived from violence; and therefore be considerate in the eating of Flesh or Fish, or any thing not procured but by the death of some of our fellow creatures; rather let them content themselves with the Delicacy of the Vegetables, which are full as nourishing, much more wholesome, and indisputably innocent…62

He once produced a plan for a Society of Clean and Innocent Livers based on ‘Rules of Cleanness, Self-Denial, and Separation’ and a Sublime merciful diet, but it was never put into practice; though famous, and even fashionable (the poet Aphra Behn was an admirer), he undoubtedly suffered some social derision on account of his vegetarianism—not least because his wife, though sober in other things, refused to give up meat.63 But Tryon was certainly a proponent of Cold Regimen, and alert to the experimental work of the Moderns. His campaign against hot drinks, hot feather beds, and hot-coddling children and swaddlingbabies—‘lapping of them up in several Double Clothes and Swathes, so tight, that a Man may write on them’—was firmly in tune with the medical teaching of his fellow Londoner Thomas Sydenham.

With the work of Galileo and the Italian anatomists, William Harvey’s discovery of the blood circulation in 1628, René Descartes’s philosophical work on mechanical physics in the 1640s, the work of the chemists, and the appearance of the practical microscope, seventeenth-century European science was more austerely rational, practical, and certainly more ‘mechanical’ than the speculative Paracelsianism of the sixteenth century. During the Civil War in England (1642–60) much serious and lengthy experimental work had gone into the Baconian project of capturing the power of nature, through agricultural reform, engineering, and statistical demography; but although Commonwealth debate had ranged widely over a number of idealistic, administrative plans for the health of the people, no parliamentary action was taken. It was a scientifically inclined prince, Charles II, who established a neo-Baconian research institute, the Royal Society, in 1662. One of the key experimental sites of seventeenth-century European science was the observation and testing of the qualities of the ‘Element of Air’. Ordinary, simple, clean cool Air—the breath of heaven—is where English ascetic physiology finally made its mark.

The Greek model of good odours and bad miasmas was, in the seventeenth century, held to be true beyond doubt, a cornerstone of science, but one whose essential arcana and mechanisms had yet to be found. Sanctorius had proved that the body breathed out a miasma of perspiration; the chemists had discovered gases but had not yet discovered oxygen, and were in the processing of discovering that plants breathed too. In addition to pure science, there were pressing medical and social reasons for investigating air, namely the controversial medieval plague policy of ‘aerial quarantine’—barricading the air into the house by closing the door on it, purifying it with good odours, and sealing it away from the contagions raging outside (or inside). Yet was it not also seen that air was worst when it was shut up and confined? Seventeenth-century writers on plague were highly concerned about the movement of wholesome air: ‘oftentimes it is seene, that sick folks doe recover their former health onely by a change of air’.64

Thomas Sydenham (1624–89), the so-called Father of English Medicine, was a fever doctor and follower of Hippocrates who spent years measuring the epidemics of London and carefully observing his patients. Like the Methodists, he thought that the patient should not be trampled on by ‘Physic’, and that a doctor’s aim should be to ‘Assist Nature’ through therapeutic nihilism: ‘truly I sometimes thought, that we can scarcely proceed too slowly in driving away diseases, and that we should proceed slowly, more being often to be left to Nature, than is now generally imagined’.65 By ignoring the medical rules and trusting to natural instinct Sydenham successfully dispensed with the conventional fever regimen, and obtained a huge reputation. The mistake of earlier physicians, he said, had been to have ‘prescribed the hottest remedies and method for those Diseases, which required above others the coldest remedies and Regimen, [as] is evident enough both in the smallpox (which is one of the hottest diseases in Nature) and in the cure of Fevers’. The fever should not be stoked up with great fires, sealed rooms, hot drinks, thick odours, and loads of blankets: for ‘how can we certainly tell that we may not kill the Man, while we endeavour to dispose the Humours to Sweat by a Hot Regimen, and hot cordials… it is clear to me, that the Fever alone has heat enough itself; not needs it any greater heat from abroad, by a Hot Regimen’. The patient only needed cool beds, plenty of cool drinks, cool air, and no bloodletting: ‘the sick must keep up a days, at least some hours, or at least lie outside the Bed… forbidding the use of Broth of any kind, permitting in the meanwhile the accustomed exercise, and free Air, without so much as once using any Evacuations’.66

Sydenham’s methods meant that the sickroom, or bedroom, became a very different place to the traditional sealed and heated chamber. We can imagine that many ‘modern’ householders threw open their windows with relief to let the fumes escape, especially in the summer. They may even have started aerating their old feather beds, for the cogent reasons given by Thomas Tryon in his domestic manual A Treatise of Cleanness in Meats and Drinks, of the Preparation of Food, the Excellency of Good Airs, and the Benefits of Clean Sweet Beds. Also of the Generation of Bugs, and their Cure (1682):

Now Beds for the most part stand in Corners of Chambers, and being ponderous close substances, the refreshing Influences of the Air have no power to penetrate or destroy the gross humidity that all such Places contract… Not that everyone’s Bed does smell indifferent well to himself; but when he lies in a strange Bed, let a Man but put his Nose into the Bed when he is thoroughly hot, and hardly any Common Vault is like it… You are to set your other sorts of Beds as near as you can to the most Airie Places of your Rooms, exposing them to the Air the most part of the day, with your Chamber-Windows open, that the Air may freely pass, which is a most excellent Element, that does sweeten all things and prevent Putrefaction. In the Night also you ought not to have your Window-Curtains drawn, nor your Curtains that are about your Beds; for it hinders the sweet refreshing Influences of the Air…67

According to one early eighteenth-century cold bather, John Hancocke, it was Sydenham and Richard Mead together ‘who, so far as I know, broke the Ice, as to the cool Regimen’.68 Cold Water joined naturally with cool beds, cool vegetables, and cool air, and rounded off the total commitment to ‘cold’ hygiene. Hancocke’s own mentor was Sir John Floyer, the highly influential author of An Enquiry into the Right Use and Abuse of Hot, Cold, and Temperate Baths in England (1697) who had made it his mission to exhort ‘The Present Age’ to ‘leave off the imprudent use of Hot Baths, and to regain their ancient natural vigour, strength, and hardiness by a frequent Use of Cold Bathing’. A stern mechanist and Sanctorian, he demonstrated how Cold Baths beneficially ‘stopped the pores’, compressed ‘the juices and the internal rarefy’d Vapours’, and gave a pleasurable after-glow—‘a great warmth all over’—with the body becoming ‘much more nimble, and [the] Joints more pliant’. The stimulating Cold Bath was excellent for the jaded appetite, and physical weakness, whereas hot baths made ‘the body weaker, the Spirits exhausted’.69

The indications are that hardy cold bathing was already on the increase as Floyer wrote, partly owing to the increased European interest in river-swimming. In England, William Pearcy’s The Compleat Swimmer, or, The Arte of Swimming appeared in 1658; and Melchisedech Thevenot’s The Art of Swimming …Done out of French, in 1699. The Cambridge natural philosophers were keen swimmers in the 1680s. The rectangular stone-lined sunken pool in the Fellows’ garden at Christ’s College (adorned with busts of John Milton and the famous Platonist Master, Ralph Cudworth) was the first swimming pool in Cambridge; there was a swimming pool of similar date at Emmanuel College. As well as using the river ‘backs’, the students frequented a stone bath built at the Moor Barns cold spring a mile from the town.70 In his next book, The History of Cold Bathing: Both Ancient and Modern (1706), Floyer gave the classical antecedents—‘I publish no new doctrine, but only design to revive the Ancient practice of Physick in using Cold Baths’—and reported that the swimming pool building craze was well under way:

There are a great many Cold Baths lately erected in England, and next to Mr Baynard’s, is that at Bathessen. ‘Tis in the grounds of Dr Parton, and by him built… The Honourable Charles Stanley Esq, brother to the present Earl of Derby, has made a Noble Cold Bath in Gripping Wood, near Ormskirk in Lancashire. I am told he had made it a very compleat Bath, with all the usual conveniences.71

The cooling doctrine in English physiology spread steadily through the wider public from its first beginnings in the fever literature. When Richard Mead published his Short Discourse concerning Pestilential Contagion in 1720, advising a reversal of the policy of confining people (and their air) during the plague, it rushed through five editions in one year, bought by a grateful public.72 Tryon’s bed campaign was also successful. During the eighteenth century the free-standing bed, with a straw or horsehair mattress, a padded quilt, and without curtains, began to come into general use. But the Stoic regime of physical ‘hardiness’ from cold bathing and cold air would not have progressed quite so far in the next two centuries, had it not been for the philosophy of John Locke.

In Some Thoughts concerning Education (1693) John Locke commented: ‘Everyone is now full of the miracles done by cold Baths on decayed and weak constitutions, for the recovery of health and strength; and therefore they cannot be impracticable or intolerable for the improving and hardening the bodies of those who are in better circumstances.’73 It was Locke (1632–1704) who gave final weight and gravitas to the Cold Regimen, and prepared the ground for its general dispersal. His Essay concerning Human Understanding (1690) was a treatise on the philosophy and psychology of ideas which led not only to a new European physiology of sensation, but to the first stirrings of European ethnography. Locke’s early career as a tutor and teacher was summarized in his next book, Some Thoughts concerning Education, which gave the English gentry advice on how to bring up their children in a bracing but humane Roman style. Although the physiological details have often been treated as harmless eccentricities, they were integral to the Lockean project of physically training the senses, in the classic traditions of gymnosophy. Like Erasmus, Locke believed in the concept of the tabula rasa—the clean, innocent, empty page of the child’s mind. In Locke’s view, the mind was gradually filled with whatever moral ideas society chose to impart; but whatever was first impressed on the human mind stayed for ever; and therefore careful training of the primary and secondary senses was essential. In classical gymnastics strength of mind went with strength of body: Locke liked to quote Juvenal’s aphorism ‘a healthy mind in a healthy body’ (mens sana in corpore sano), calling it ‘a short but full description of the most desirable state we are capable of in this life. He who has these two has little more to wish; and he that wants either of them will be but little better for anything else.’74

Many of Locke’s ideas would have already been familiar to the humanist-trained, reform-minded, patriotic, late seventeenth-century English reader. His educational programme was designed to turn their sons into Stoic young warriors with ‘strong constitutions, able to endure hardships and fatigue’—unlike ‘most children [whose] constitutions are either spoiled, or at least harmed, by cockering and tenderness’. The boys should mostly play in the open air, ‘and as little as may be by the fire…thus the body may be brought to bear almost anything’.75 The whole plan was set out in a few easily observable rules: ‘Plenty of open air, exercise and sleep, plain diet, no wine or strong drink, very little or no physick, not too warm or straight clothing, especially the head and feet kept cold, and the feet often used to cold water, and exposed to wet.’76 The girls, too, were included in this regime: ‘The nearer they come to the hardship of their brothers in their education, the greater advantage they will receive from it.’ He was particularly disapproving of girls’ strait-lacing and stays, stopping the circulation and compressing the stomach: ‘That way of making slender wastes, and fine shapes, serves but the more effectually to spoil them.’77

The change in English children’s fashion towards looser cotton clothing, for boys and for girls, dates from this period. Boy’s clothing should be thin and light, with no cap, and open shoes—‘with holes in his shoes so that they leak’—in other words, sandals. The stockings should be changed and the feet washed every day in cold water (a custom that may have led to the invention of boys’ ankle socks): ‘I fear, I shall have the mistress and maids too, against me… It is recommendable for its cleanliness; but that which I aim at in it, is health.’ Locke approvingly quoted Seneca on cold baths in midwinter, on the cold-bathing of infants by the Germans, Irish, and Scots ‘of old’, and thought learning to swim was essential: ‘It is that saves many a man’s life, and the Romans thought it so necessary that they ranked it with letters… the advantages to health, by often bathing, in cold water during the heat of the summer, are so many, that I think nothing need be said to encourage it.’78 Locke’s Roman hardiness, his Greek athleticism, and his Protestant naturalism clearly appealed to large numbers of the English upper classes; it was a fitness regime that many English public schoolboys endured until quite recently, including daily morning plunges into cold water (even the sea), deep winter only excluded.79

There was an obvious transformation in the idea of cleanness in England in the seventeenth century. The association of coolness, cleanness, and innocence appears to have emerged directly from Protestant sectarianism, blended into a formal, neoclassical framework that had reincorporated the Greek regimen of the non-naturals. The more extreme health or hygiene beliefs (whether it was the Sanctorian Sober Diet, the Mean Diet, the Vegetable Diet, or the Cold Bath) were undoubtedly held only by a rather small constituency of ascetic self-experimenters, people of independent thought and means, or invalids who needed to mend their health. But the sheer numbers of references to the actual words ‘Cleanliness’ or ‘Cleanness’ had grown extraordinarily and were much more portentous than before, certainly when highlighted (as they so often were) with a capital letter. In the following century Cleanliness was to become far more Rational. Religious mysticism gave way to a strong presumption in favour of its usefulness in disease prevention as many further scientific ‘proofs’ of the utility of hygiene were presented, confirming the truth of Mead’s dictum: ‘as Nastiness is a great source of Infection, so Cleanliness is the greatest preservative: which is the true reason, why the Poor are most obnoxious to Disasters of this kind’. The general public in eighteenth-century England were to be targeted yet again by health educationalists, for the general good of an extremely affluent new commonwealth.