’That the inhabitants of this kingdom have of late years changed their way of living in a very remarkable manner, and greatly increased in luxury, is a truth of which every person, who has lived any time in it, must be sensible,’ wrote the economist Adam Dickson in 1773.1 By then the age of ‘heroic’ sectarian Protestantism had long passed; Quaker Friends no longer interrupted sermons or went naked in the street while they were busy making their fortunes. Borrowing a phrase from John Bunyan, the old Dissenters were crossing ‘the plaine of Ease’, at the edge of which lay ‘a little hill called Lucre, and in that hill a silver mine’, beyond which stood ‘Doubting Castle’. The new United Kingdom’s population rose steeply from c.10.5 million in 1750 to 15.5 million in 1801. There were only four new bodies of English local civic Improvement Commissioners set up between 1700 and 1749; over the next fifty years, by 1800, there were 567.2

The hygienic changes during the first fifty years of the eighteenth century were still mainly personal and economic ones—most of them occurring in people’s minds and inside private homes. The result was a new market for health care. The thriving eighteenth-century health and leisure industries were blatantly connected to the fast-accelerating ‘wheel of fashion’—a new vortex of consumerism that had emerged from unprecedented European mercantile expansion and surplus wealth.3 But life was still harsh, brutal, and short if you were born at the bottom of the heap; and there was only the germ of an idea, around 1750, that these immemorial conditions could be ‘improved’. In the second half of the century, in England, France, and Germany especially, there was renewed interest in the utility of public hygiene, coupled with the first tentative moves towards hygienic public health policies, based on statistics and natural science. Just to keep these wider social developments in perspective, however, the leap of the imagination required to make a connection between the old idea of private hygiene and new idea of public hygiene is reflected in this footnote from the amateur health bibliophile and reformer Sir John Sinclair, uncertainly attempting to redefine personal hygiene as a social science in 1802:

Good health and longevity depends much upon personal cleanliness, and a variety of habits and customs, or minute attentions that it is impossible here to discuss. It were much to be wished, that some author would undertake the trouble of collecting the results of general experience upon that subject, and would point out to those habits, which, when taken singly, appear very trifling, yet when combined, there is every reason to believe, that much additional health and comfort would arise from their observance.4

Only five years later, however, he was confidently advocating the new European philosophy of ‘medical police’, namely,

1. Police of Climate. 2. Police of Physical Education. 3. Police of Diet. Police of Public Amusements. 4. Police of Habits and Customs. Police of Public Institutions. 7. Police for the Health of Soldiers and Sailors. 8. Police to Prevent Contagious Disorders. And, 10. Police of Medicine and the means of promoting its improvement.5

The overriding image of eighteenth-century Europe is one of supreme elegance: the perfect ‘Quality’ lifestyle of the aristocracy, gentry, and educated middle classes, for whom personal cleanliness and orderliness were now very visible marks of being ‘genteel’. The large personal fortunes made in eighteenth-century Europe were discreetly covered by the cloak of fashionable French politesse. In France a new style of ‘liberal’ or ‘open’ manners had slowly replaced the more rigid formal manners of the seventeenth century, and smoothed the way for wealthy upper-rank aspirants: the social formalities were to be entered into easily and naturally, in leisurely informal gatherings. In England liberal French manners sat easily with liberal English politics, and spread out from London into the provinces via the bustling English presses. Anxious queries about correct social manners peppered the pages of the Spectator magazine, where old-style courtiers were mocked as old-fashioned, since ‘our Manners sit more loose upon us’; and in the 1714 issue the editor, Joseph Addison, tackled the subject of Cleanliness. He quoted the classics and called cleanliness a Half-Virtue, lying somewhere halfway between duty to God and duty to society:

It is evident that Cleanliness, if it cannot be called one of the Virtues, must ever rank very near them: from age to age it has ever been admitted that ‘Cleanliness is next to Godliness’; it is the mark of politeness; it produced love; and it bears analogy to purity of mind; Aristotle calls it one of the Half-Virtues. No-one, unadorned with this virtue, can go into company without giving manifest offence; and the easier or higher anyone’s fortune, this duty rises proportionately. The more any country is civilised, the more they consult this part of politeness.6

The early eighteenth-century founder of Methodism, John Wesley, in turn quoted Addison, in a sermon on dress: cleanliness was, firstly, ‘the mark of Politeness’, secondly, the ‘Foster-mother of Love’, thirdly, indicated ‘Purity of Mind’, and fourthly, was a ‘preserver of Health’. He was known to be personally fastidious, and was insistent on cleanliness among his followers: ‘Be cleanly. In this let the Methodists take pattern from the Quakers. Avoid all nastiness, dirt, slovenliness, both in your person, clothes, house, and all about you. Do not stink above ground. This is a bad front of laziness; use all diligence to be clean…’.7 In Addison’s and Wesley’s definitions, cleanliness was still very much cast in its traditional courtly mode, predominantly a social virtue, a sign of good breeding, and a sine qua non of beauty and elegance. Clean linen, clean hands, and precision grooming marked the gentleman, as well as good manners; this Ovidian model is recalled in one of Lord Chesterfield’s famous letters to his son, in 1750:

My Dear Friend. You will possibly think that this letter turns upon strange, little, trifling objects; and you will think right, if you think of them separately; but if you take them aggregately you will be convinced that as parts, which conspire to form the whole, called the exterior of the man of fashion, they are of importance. I shall not now dwell upon those personal graces, that liberal air, and that engaging address, which I have so often recommended to you, but descend still lower, to your dress, cleanliness, and care of your person… Take care to have your stockings well gartered up, and your shoes well buckled; for nothing gives a more slovenly air to a man than ill-dressed legs. In your person you must be accurately clean; and your teeth, hands, and nails should be superlatively so…. The lowest peasant speaks, moves, dresses, eats, and drinks, as much as a man of the first fashion, but does them all quite differently; so that by doing and saying most things in a manner opposite to that of the vulgar, you have a great chance of doing and saying them right. There are gradations in awkwardness and vulgarism, as there are in everything else.8

But how could you tell what these subtle ‘gradations in awkwardness’ were? Eighteenth-century English fiction was full of nuanced and didactic examples of good manners, which were certainly used as an aid to self-education. Meanwhile, the slow seepage of ‘polished’ manners down the social scale opened up an even greater gulf between the literate ‘polite’ and those without these new manners, the illiterate vulgar.

’The cleanliness of the rest of your person, which, by the way, will conduce greatly to your health, I refer from time to time to the bagnio,’ remarked Chesterfield casually, but not urgently.9 He might have known better than to send his son to France with that advice—or perhaps he assumed that French aristocratic males merely looked on while their womenfolk bathed and sluiced. In France the aristocratic tendre for cosmetic cleanliness that had developed during the seventeenth century had reached a new peak of perfection by the eighteenth century. It had virtually become a symbol of their class. The cultic aspects of the boudoir came from the French royal ritual of the levée, the morning toilette conducted in the royal bedroom suite with an audience of kin, intimate friends, and favoured counsellors, an old custom of monarchs that had been perfected by Louis XIV, and which spread throughout the French nobility—a new and highly favoured grooming pleasure zone, full of objets d’art.10 Toilet sets were increasingly given as wedding gifts, individual items came as love gifts, and visitors were meant to be impressed by the immense profusion of silver, gold, and glassware on the toilet table:

And now, unveiled, the Toilet stands displayed,

Each Silver Vase in Mystic Order laid.

First, rob’d in White, the Nymph intent adores

With Head uncovered, the Cosmetic Powrs …

This Casket India’s glowing Gems unlock,

All Arabia breathes from yonder Box.

The Tortoise here and Elephant unite,

Transformed to Combs the speckled and the white.

Here Files of Pins extend their shining Rows,

Puffs, Powders, Patches, Bibies, Billet Doux…11

Well-made French cosmetics and perfumes were all highly desirable; they were imported (even smuggled), and then flaunted, by aristocracies all over Europe.

Perfumes, powders, and paints now arrived in easy-to-use luxury packaging; intrinsically they remained largely unchanged, but their application had become a high art form. Needless to say, strong perfume accompanied every possible item of the toilette, including scented mouth pastilles, toilet waters, and moisturizing creams. Clutching their white, red, and yellow greasepaints—their pomades á la baton—women designed the precise colouring of their faces—their maquillage—like artists in front of a canvas. Body depilation, eyebrow-plucking, eye black, rouge lip salves, and innumerable shades of rouge powder for the cheeks were de rigueur; and the new fashion for powdering the hair with scented powders and greasing it to form sculptural piles over inserted padding started early in the century. The infamous ‘high’ hairstyle, however, was only fashionable for a short-lived decade during the 1770s; women soon reverted to the more comfortable and easily maintained ‘low’ styles that had been normal between 1715 and 1770.

Underneath the façade things were not always so glamorous—we know enough about the fleas, lice, smeared paintwork, and powerful body odours to be sure of that. Some at least of the heavy painting can be attributed to the ravages of smallpox, then an endemic childhood disease, or to syphilitic disfigurement. There were certainly hygiene problems connected with wear and storage of clothes and wigs; although when well kept, with cropped hair underneath, wigs would have reduced nits and lice considerably. Although the parasite load was obviously still relatively high, multiplying with every increase in population and only held in check by constant manual grooming, it was now beginning to be deterred by regular domestic bathing. Among the female French aristocracy the bath had become an indispensable part of the toilette, and was constructed from the choicest materials: marble, bronze, painted and lacquered metal, or even crystal glass. Very select visitors were received in the luxurious surroundings of the cabinet de bain, which, as the ever-growing genre of titillating French bath paintings show, was an arena of unabashed sexual display. The profusion of new bathing furniture and toilet articles, however, indicated a more serious grooming intent. French cabinet-makers designed new and convenient washstands, holding a large jug and basin, with little drawers, mirrors, and other contrivances underneath, which were then copied by local manufacturers; they became an indispensable item for shaving and grooming in male quarters. The newly invented French bidet, a chairlike washstand for sluicing the private parts, was used by men and women alike; it was often taken on travels and military campaigns, and became a mark of supreme cleanliness among the French upper ranks.12

The other supremely private part was the mouth. Paris was the centre of advanced dentistry in the mid-eighteenth century, with patients arriving from all over Europe to get their teeth mended and their dental hygiene improved. A new vogue for le sourire (the smile) began to affect French manners; in 1787 the artist Elizabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun broke with formal tradition and painted the first romantic open smile, with gleaming white teeth, in European art history.13 Rotting teeth and bad breath were an extremely common and painful problem, made worse by rising imports of sugar, and sticky fruits and sweetmeats, which the older methods of soft leaves, sticks, or cloths could scarcely deal with; and a lot of damage was done by using coarse or badly ground powders, ashes, and whiteners (chalk, salt, soda), which wore the enamel or irritated the gums. Chesterfield (and many others) badly damaged his teeth through the over-energetic use of ‘sticks, irons, etc., which totally destroyed them, so that I have not now above six or seven left’. If a whole family suffered from poor teeth, the dentist’s bills could be a minor financial disaster. Towards the end of the century standards of dental hygiene were improving among the upper classes, even outside France. English gentry-folk would have been aware of the surgeon John Hunter’s handbook on the teeth The Natural History of the Human Teeth: Explaining their Structure, Use, Formation, Growth, and Diseases, after 1771; and new soft toothbrushes and purer pastes arrived slowly, in the last third of the century—William Cowper in rural retreat had to send for his new toothbrushes from London, commenting ‘people do not brush their teeth at Olney’.14

The bidet may have been a step too far for many foreign consumers. Advanced cosmetic lore was still clearly absent in Protestant England, where heavy or excessive painting (including lip- or eye-painting) was generally frowned on, and more exotic cosmetic techniques (nail paint, depilation) were virtually unknown among the virtuous. All the exposed parts were expected to be kept as clean as possible, and there were plenty of washes, lotions, and whiteners available in the old receipt books that did just that; but the more intimate demands of the body were apparently often simply ignored, in chaste Christian fashion. On the regular female menstruation, ‘the curse’, and its personal hygiene problems and difficulties, there was (it seems) a general silence, according to the liberal physician William Buchan:

there are no women in the world so inattentive to this discharge as the English; and they suffer accordingly, as a very great number of them are obstructed, and many prove barren in consequence… False modesty, inattention, and ignorance of what is beneficial or hurtful at this time, are the sources of many diseases and misfortunes in life, which a few sensible lessons from an experienced matron might have prevented.

The normal method of dealing with menstrual flow was to cut out and sew a pad of rag, which was then pinned onto the underpetticoat and washed daily, a method which persisted well into the early twentieth century.15

But even in these small matters, things were improving. An imported Indian technology—lighter cotton cloth—was beginning to make ‘shifting’ far easier in Europe, at the same time as increasing the amount of underwear required to be frequently laundered. Cheaper cotton in the second half of the century was a godsend for the middling classes. Raw cotton imports to Britain soared as mass production took off: printed cotton, using engraved copper plates, arrived in the 1750s, and mechanized roller-printing started another boom in the 1780s, paving the way for mechanized spinning forty years later.16 It was also during the 1780s, that the infamous chemise à la reine—a white muslin undergarment shockingly turned into a peasant-style outer garment—served as the precursor of all the lighter, softer, sprigged muslin fashions to come. Perhaps not uncoincidentally, cotton ‘drawers’ or underbreeches (pantaloons) for women first appeared at the end of the century—a usage previously confined to men.17 During the seventeenth century the quantity of laundering per household had doubled, and had gradually developed into two forms: the Great Wash for larger items, and the Small or ‘slop’ Wash for small items of body linen, usually done by the month or the season. By the mid-eighteenth century town households would be regularly doing at least one of these washes once a week.18

In Britain the lessons of the plague had been learnt; and a passion for science had translated into a passion for ‘improved’ domestic architecture. Domestic engineering was reassessed hygienically in the Greek manner (the Palladian Greek style went down particularly well in the brand-new houses built by affluent eighteenth-century colonists in North America) resulting not only in many thousands of Greek frontal pediments but in the redesigning of gardens (for outdoor exercise); of larger windows and rooms (for light and air); of kitchen stoves and smaller fireplaces (for cleaner and more controllable heat); and of plumbing and laundries (for washing and sanitation). ‘Convenience’ was the word most often used to describe these new domestic changes: when something was convenient, it meant it was neater, cleaner, and easier to use or maintain. The large rise in the servant population reflected the quantities of new goods to clean and look after: acres of polished flooring, marquetry, ormolu, marble, glass, mirror, silver, porcelain, chandeliers, books, tableware, and musical instruments.19 So much ellu everywhere: gold-leaf glinted throughout these domestic temples. And as each modern convenience or objet d’art arrived, it became a minor luxury that could shortly without too much difficulty be copied, redesigned, and installed to fit the demands of the rather smaller houses and tighter pockets of the increasing numbers of moderately prosperous gentlefolk—a market that Josiah Wedgwood and hundreds of other small domestic manufacturers quickly discovered and supplied. By 1861 in Britain, one in three women between the ages of 15 and 24 was a household servant.20

For most of the English (and colonial American) upper classes the bidet was probably regarded with stupefaction (they were still not thought convenable in Anglo-Saxon homes until the second half of the twentieth century). But the influence of rationalism and natural philosophy was nonetheless making itself felt. Even in early eighteenth-century England puritanical attacks on the Art of Beauty were beginning to seem old-fashioned, irrational, and irrelevant, and the dogmatic Christian doctrine on cosmetics was fading fast.21 By the mid-century quite a lot of English prejudice about warm bathing was starting to be laid to rest as new ‘foreign’ habits and practices of balneology took hold. Queen Caroline had brought her German bathing habits with her from Ansbach when she came to the throne in 1727, and immediately ordered a full set of tubs for the whole royal family so that they could bathe regularly: footbaths, small or half-baths, body baths, and even double tubs—the ‘very large body bath’. But there was still a long way to go in converting the English gentry, and the warm bath was still a novelty in 1741:

I have suffered great disappointment about the warm bath, which I was advised to try, for the bathing tubs are so out of order we have not been able to make them hold water, but I hope this week they will serve the purpose … I pray Ivole for my bathing dress, tell her I must go in in chemise and jupon,

wrote the gentry traveller Elizabeth Montague, obviously taking her warm bath very modestly in loose clothing, sitting on a stool inside the normal draped and filled bath, with her handmaiden sluicing her with more hot water (how bathing-dresses and caps helped or hindered these arrangements is a moot point).22 At the beginning of the century many English gentry country houses had successfully begun to tackle the problems of water engineering and plumbing, and by the 1730s many of them could, in theory, have had running water on all floors and as many baths and water closets as required; but apparently most owners did not fully avail themselves of this technology until the 1780s. Clearly the older methods, and more limited water sources, still sufficed; at least until a far more efficient type of ball-valve water closet latrine was invented by Joseph Bramah in 1778, which was definitely a spur to reform: by 1797 Bramah claimed to have made 6,000 closets. Flushed water closets, being an English invention, were joyfully called les lieux à l’anglaise in France (roughly translatable as the ‘English shit place’); but the built-in plumbing they required was not considered a necessity in France until the later nineteenth century.23

Further interesting balneological experiences occurred when West met East in British colonial India. British travellers and residents in early eighteenth-century India were at first overwhelmed by its culture; they lived in their houses in the Indian manner, wore Indian muslins, copied the umbrellas, and were fascinated by Indian vegetarianism, medicine, botany, and philosophy. It was an open window that was to close quite quickly at the end of the century as the British Raj got under way. European colonialists had rapidly discovered that perfect bodily cleanliness was expected of them in accordance with the caste system, and was essential to the authority of their rule. Among other things they were fascinated by the deft and rapid daily Indian strip wash, the expert Indian champu, or ‘shampoo’ massage, and the ease of the Indian shower-bath, all of which became widely adopted in Indian colonial circles—habits which they then later brought back home.24 Elsewhere, diplomatic wives discovered the hot-vapour Turkish baths of Constantinople or northern Africa when they were invited into aristocratic female harems (like Lady Mary Wortley Montagu) and wrote about them in their correspondence.

Attitudes towards personal hygiene had thus changed dramatically during the course of the century, under French influence. Luxurious boudoir bathing was at its height in France under Napoleon in the 1790s, by which time baths (or showers) had become essential items in most aristocratic dressing rooms. The period 1792–1815 was the era of the famous Directoire or empire line, where the confining ribbon emphasized the breasts, and the lines of the naked body were shown sensuously beneath light muslin. Being ineffably hygienic and classical, the mode came complete with Grecian drapes and light Grecian sandals—open sandals on bare feet with which nailpolish was worn, and shorter, cleaner, haircuts—the Grecian tomboy look, or the Grecian diadem-and-topknot. For men, the heavy brocaded cloth, wigs, hair powder, and facepaint of the aristocracy were abandoned, replaced by the plain, sober, but well-tailored English morning suit (originally a sporting riding suit), immaculate linen, no powder, and windswept, romantic hairstyles.25 The fashion for hair powder thus slowly disappeared (the British Army abandoned hair powder after hygienists pointed out that it tended to turn to paste in the rain).26 In the 1790s, even in London, ‘revolutionary’ standards of French hygiene were deemed fashionable: ‘This simple and delightful affair of bathing the private parts and the fundament everymorning, summer and winter—is of more importance to the bodily health, youthful beauty and sweet desirableness of men and WOMEN, than anything I can possibly mention or inculcate.’27 But up until the end of the century it seems quite likely that the water that mostly touched British (and Anglo-American) bodies ‘all over at once’, during most of the eighteenth century, was probably cold; and that the personal hygiene that they knew most about was the one that came from books.

Travellers to eighteenth-century England constantly pointed out—with a certain wonderment—how excessively fond of strenuous physical exercise the English were. The romantic English parkscape that developed in the first half of the century had long informal paths that rambled around the estate towards newly built plunge pools, cricket pitches, stables, and carriage rides, fishing lakes, archery butts, boatsheds, and carefully placed picnic pavilions. The aristocracy spent their time royally feasting and sporting and then recovering from it: ‘The Pretty Duchess of Devonshire… has hysteric fits in the morning and dances in the evening; she bathes, rides, and dances for ten days, and lies in bed the next ten.’28 What foreigners were seeing, in part, were the older forms of pleasure reinforced and given cachet by Locke’s hygienic regimen.

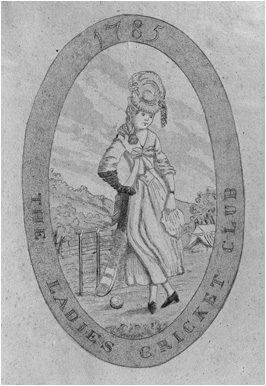

14 An unknown Ladies Cricket Club, 1785, showing the hygienic revival of women’s sports in later eighteenth-century England. Note the short skirts and sensible shoes.

The events of the seventeenth century had left the British upper classes well primed in science. Isaac Newton and John Locke had enshrined the status of science in Britain—Newton had had a state funeral, which profoundly impressed Voltaire. Between 1700 and 1770 the medical advice book market expanded intermittently but steadily, especially for works that took apart one or other of the non-naturals in detail—a style first explored in Richard Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621–38).29 Readers were evidently sufficiently well versed in regimen to appreciate the growing debates on the Air, Diet, Exercise, Sleep, Evacuations, and Passions of the Mind, a trend picked up by the physician-author John Arbuthnot, who wrote two influential digests for general readers, An Essay concerning the Nature of Aliments (1731), and An Essay concerning the Effects of Air on Human Bodies (1733). An early best-seller was George Cheyne’s Essay on Health and Long Life (1724), a semi-vegetarian Cornaroian text that explored diet, exercise, and weight loss using a quantity-controlled ‘low’ diet of milk, white meat, vegetables, and fruit. He told patients to monitor their weight using a Sanctorian chair, and to ‘make exercise a part of their religion’.30

Francis Fuller’s Medicina Gymnastica (1705; six editions by 1750) set the tone when he announced the arrival of modern Rational mechanical doctrines and denounced old humoral methods—‘our too partial Consideration of the Body of Man, by attributing too much to the Fluids, and too little to the Solids’. The Cartesian-Newtonian Rational physiology emerging from the new northern Protestant universities recently opened in Leiden, Edinburgh, and elsewhere now saw the solid body in mechanical terms of pumps, ducts, and vessels, mass and flow, contraction and relaxation, entrances and exits. The pores of the skin, for example, were now likened to little valves, opening and closing on the surface; or smoky chimneys exhaling the hot vaporous excrements.31 Muscular vigour was essential: a vigorous circulation carried off the poisons quicker and ‘braced’ the solids to perform their proper actions. Although Galenic bleeding and dieting was still a prop which many physicians (and patients) were loath to abandon, anything ‘bracing’ was considered excellent for stimulating the evacuations of the insensible perspiration—given off in a healthy, sweaty ‘glow’. Fuller was greatly in favour of cold bathing for this purpose, ‘a severe Method of Cure taken up lately among us … yet we see now the tenderest of the Fair Sex dares commit herself to that terrible element’. According to the bibliographer Charles Mullet, British bathing book lists reflect the influence of John Floyer from the 1720s, followed by a mid-century burst of scientific activity, after which ‘the tide of balneological literature flows ever higher’.32

In the most widely read and quoted health poem of the century, John Armstrong’s The Art of Preserving Health (1744), Hygieia was a stern and chilly goddess, and hardiness was her second name:

’Tis not for those, whom gelid skys embrace …to cultivate a skin

Too soft; or to teach the recremental fume

Too fast to croud through such precarious ways …

Study then your sky, form to its manners your obsequious frame,

And learn to suffer what you cannot shun.

Hardiness in a cold climate appeared to make perfect sense. Eighteenth-century Britain was the golden age of commercial freelance medicine (university-trained or otherwise), unrestrained by legislation or strict codes of professional ethics; and faced with a bewildering array of medical operators many people preferred to put their trust in the new hardy preventive regimen.33 Personal regimen had now become a constant topic of conversation, like the weather, when there was little else to say; some eighteenth-century diaries and journals often recorded little else but their owner’s non-natural health regime. It was often accompanied by the culture of invalidism, or the habit of constant ‘complaining’ about infirmities (probably the best-known regimen bore in literature is Jane Austen’s valetudinarian Mr Woodhouse, with his very accommodating surgeon, Perry).34 Though the sources have yet to be thoroughly combed for devotees of the Lockean or Spartan lifestyle, it can emerge offhandedly in letters. Thus we find out that the indefatigable Horace Walpole was indeed indefatigable, and had trained himself to be so, since the 1730s. Writing in 1777 at the age of 60 to a friend who was obviously urging him to take things easy, he replied:

I know my own constitution exactly, and have formed my way of life accordingly. No weather, nothing gives me cold; because, for these nine and thirty years, I have hardened myself so, by braving all weathers and taking no precautions against cold, that the extremest and most sudden changes do not affect me in that respect. Yet damp, without giving me cold, affects my nerves; and, the moment I feel it, I go to town … I am preached to about taking no care against catching cold, and am told that I shall one day or other be caught—possibly: but I must die of something; why should not what has done to sixty, be right? My regimen and practice have been formed on experience and success … everything cold, inwardly and outwardly, suits me. Cold water and air are my specifics, and I shall die when I am not master of myself to employ them …

And to another friend, still at it at the age of 65:

A hat you know I never wear, my breast I never button, nor wear great-coats, &c. I have often the gout in my face (as last week) and eyes, and instantly dip my head into a pail of cold water, which always cures it, and does not send it anywhere else. All this I dare do, because I have so for these forty years, weak as I look…

Christ! Can I ever stoop to the regimen of old age? …to sit in one’s room, clothed warmly, expecting visits from folks I don’t wish to see.35

He died, alas, an incapacitated valetudinarian who had to be carried from room to room—but no doubt on his own terms.

Cold water was now being copiously applied as a universal cure-all. In his famous work Primitive Physic (1747), which is known to have reached a very wide sectarian audience, especially among the rural puritan colonies of North America, John Wesley believed in drinking cold water for almost anything and prescribed the cold bath continuously, for example, ‘Cancer. Use the Cold Bath. This has cured many. This cured Miss Bates of Leicestershire of a Cancer in her breasts, a Consumption, a Sciatica, and Rheumatism, which she had had near 20 years. She bathed daily for a month, and drank only Water.’ The book praised Cheyne and ‘the great and good Dr Sydenham’ but also promoted radical Protestant health beliefs, railing against the doctors with their abstruse science (‘abundance of Technical Terms, utterly unintelligible to Plain Men’), their evil compound medicines (‘scarce possible for Common people to know’), and their wicked slander of wise ‘Empiricks’ and the simple folk remedies formerly used in an Arcadian state of grace and health.36 In Wesley cold water was being lauded as a folk remedy; and its contemporary revival may well have resurrected certain deep-seated water beliefs. By the mid-century in Britain the cold bathing of children and infants had apparently reached the fetish stage in the well-staffed nurseries of the rich at least, where, according to one critic, cold water had attained a semi-mystic value, and become almost a rite:

I have known some [nurses] who would not dry a child’s skin after bathing it, lest it should destroy the effect of the water. Others will even put clothes dipt in the water upon the child, and either put it to bed, or suffer it to go about in that condition. Some believe, that the whole virtue of the water depends upon it being dedicated to a particular saint; while others place their confidence in a certain number of dips, as three, seven, nine, or the like; and the world could not persuade them, if these do not succeed, to try it a little longer… We ought not, however, entirely to set aside the cold bath, because the nurses make a wrong use of it. Every child, when in health, should at least have its extremities daily washed in cold water. This is a partial use of the cold bath, and is better than none. In winter this may suffice; but, in the warm season, if a child be relaxed, or seem to have the tendency of rickets or scrofula, its whole body ought to be frequently immersed in cold water.37

See that body glow. Being rubbed raw after a freezing morning bath, every day, year after year—possibly even for life—was the lot of many British infants and adults, from the eighteenth century onwards.

The other main barometer of eighteenth-century British cold-water balneology is the existence of the baths themselves. The equipment for cold-water therapy was either very simple—like Walpole’s bucket—or very elaborate. Stone-built cold plunge baths were either put in small bathing pavilions near the house (as at Kenwood House in Hampstead), or built as small rectangular swimming pools in sylvan settings overlooking the countryside, with or without charming shell-encrusted grottoes and waterfalls.38 Commercial outdoor facilities were quickly provided for the carriage trade: the river baths run by an apothecary, John King from Bungay in Suffolk, were advertised to the ‘Physicians and Gentry in our neighbourhood’ with all the necessary conveniences: changing and eating pavilions, carriage access, bridges, gardens, plantations, boats, and bathing platforms. He had already added ‘a warm Bath, together with a Bagnio or Hummumms … accommodation rarely to be met with unless in the Metropolis or very popular places’. Surely a day out with a difference in 1737. Over on the other side of the country, the Salop Infirmary near Shrewsbury, in Shropshire, began opening its baths to the paying public from 1748; as had the mid-eighteenth-century Liverpool Infirmary, with its suite of cold baths on the ground floor, both paid for by public subscriptions. The Salop baths were opened at 1s. per person (later reduced to 6d. for adults and 3d. for children) with an extra 6d. for a hot bath: middle-class prices. The inclusion of hot baths must have seemed wonderfully practical, as well as delightfully exotic and novel, explaining the mid-century success of Bartolomeo Dominicetti’s suites of urban commercial Turkish baths for the gentry in Chelsea and Knightsbridge, and ‘particularly at York, Manchester, Newcastle upon Tyne, Bristol, and et cetera’.39

The fact that the various balneological routines were described so carefully suggests that full-body immersion did not necessarily come naturally, and was a technique that had to be learnt by the general public (or so the doctors certainly thought). The cold ‘dip’ was just as exhaustively described for the upper and middle classes in the eighteenth century, as shower-baths and the strip wash were in popular working-class advice books in the nineteenth century. Cold bathing, of course, was tremulously associated with the frightful ‘shock of the cold’. In 1771 the Delaware resident Elizabeth Drinker screwed up her courage to take the cold plunge—and hated it: ‘S. Merriot Snr., Molly Hall, Anna Humber, and Self went this Afternoon into the Bath, I found the shock much greater than I expected…. took a ride this morning to the Bath, had not courage to go in … went into the Bath; with fear and trembling, but felt cleaver after it.’ She soon gave up her attempts at cold bathing, and did not try again for twenty-eight years. She was not alone: in 1796 young Henry Tucker in Williamsburg wrote, ‘Mama has taken a bath and enjoyed it very much though at first she was quite frightened.’40 But more and more it was the lure of the sea, and the seaside, that gave cold bathing that extra zest. The main reason why fearful people forced themselves to be braced and battered by cold water was that it had become a social event, as firmly attached to communal pleasures and merrymaking as the hot stoves had ever been.

Unlike the mineral-water spa, sea-bathing resorts were not confined to certain geographical areas, and the history of British resort development is above all one of steady geographical spread. People were already cold-dipping in the sea in Lancashire and Wales at the beginning of the eighteenth century, in what seems to have been an entirely local custom. While walking the Welsh coastline in the 1790s, the poet, swimmer, and philosopher Samuel Taylor Coleridge came upon an unusual scene which he greatly admired for its innocence:

At Holywell I bathed in the famous St Winifred’s Well—it is an excellent cold bath. At Rudland is a fine ruined castle. Abergeley is a large village on the sea coast. Walking on the sea sands, I was surprized to see a number of fine women bathing promiscuously with men and boys—perfectly naked! Doubtless, the citadels of their chastity are so impregnably strong, that they need not the ornamental outworks of modesty. But seriously speaking, where sexual distinctions are least observed, men and women live together in the greatest purity. Concealments set the imagination a’working, and, as it were, canthardizes our desires.41

By the 1730s Scarborough and Margate on the east coasts were developing recognizable sea-bathing seasons, while Brighton on the south coast took the fashionable lead after Dr Richard Russell eulogized it in 1752, and became the hub of a coastal growth that spread lengthways east and west.42 In the second half of the century the seaside became closely associated with the new European Romanticism, making it even more appealing and ‘sublime’. In the 1790s a second wave of seaside resorts and inland ‘watering places’ was developed for a mass urban clientele, each successive village inexorably swallowed up in turn, as gentry health-seekers sought ever quieter or more exclusive scenery. Partly in response to British travellers’ demands, in the early nineteenth century seaside resorts began to spread steadily along the northern coasts of France and Germany, and rapidly extended to fashionable health resort developments on the southern Mediterranean French coast, the French and German Alps, the Italian coastline, and the Italian Lakes. But the most popular beaches of all were near the larger cities. In America the early inland spas and river baths were dramatically eclipsed by sea-bathing resorts springing up on the east coast: in 1794 the crowds coming out from New York to sea bathe, drink tea, and admire the views in the coastal resort at Long Island were so great ‘as to keep four large ferry boats, holding twenty persons each, in constant employ’. There were similar crowds on the coast near Liverpool during a hot August in 1791:

For a week past, upon the most moderate calculation, here has not been less than five thousand persons out of the country, for the express purpose of bathing in the sea. If to these we add five thousand of the inhabitants … ten thousand persons have daily been immersed in the briny element; and that on an extent of shore not much exceeding half a mile.43

Nothing stimulated the economy like health resorts. George Carey’s famous resort guidebook The Balnea: or, An Impartial Description of All the Popular Watering Places in England (1801) was a lively (and sarcastic) progress report on the genteel state of each of these thriving new settlements. Jane Austen’s last, half-finished novel about a mythical coastal resort, Sanditon, written during the renewed resort boom in Britain after the Napoleonic Wars in 1816–17, would undoubtedly have been a satiric masterpiece on the subject of coastal resorts and health-faddery in general. In what is left of it, it still is. Austen’s tongue-in-cheek descriptions gently but unerringly undermine all the pretensions of late eighteenth-century British balneological tourism:

’But Sanditon itself—everybody has heard of Sanditon. The favourite—for a young and rising bathing place—certainly the favourite spot of all that are to be found along the coast of Sussex…’… Mr Parker’s character and history were soon unfolded… he was perceived to be an enthusiast, a complete enthusiast. Sanditon, the success of Sanditon as a small fashionable bathing place, was the object for which he seemed to live. A very few years ago it had been a quiet village of no pretension… circumstances having suggested to himself and the other principal landowner the probability of its becoming a profitable speculation, they had engaged in it, and planned and built, and praised and puffed, and raised it to something of young renown; and Mr Parker could now think of very little besides…. ‘Civilization, civilization indeed!’ cried Mr Parker, delighted. ‘Look, my dear Mary, look at William Heeley’s windows. Blue shoes, and nankin boots! Who would have expected such a sight at a shoemaker’s in old Sanditon! This is new within a month. There was no blue shoe when we passed this way a month ago. Glorious indeed! Well, I think I have done something in my day. Now for our hill, our health-breathing hill’ …

Trafalgar House, on the most elevated spot on the down, was a light elegant building, standing in a small lawn with a very young plantation around it, about a hundred yards from the brow of a steep but not very lofty cliff… Charlotte, having received possession of her apartment, found amusement enough in standing in her ample Venetian window and looking over the miscellaneous foreground of unfinished buildings, waving linen and tops of houses, to the sea, dancing and sparkling in sunshine and freshness.44

In the second half of the century two particular scientific developments had greatly strengthened the impact of hygiene, and given the European—and American—public a whole new set of medical words to play with. Firstly, physiology took a turn towards the social sciences, towards seeing the human body en masse, observing the effects of personal hygiene from a distance. Secondly, a new phase of physiology opened up through the mid-century discovery of the nervous system, which ultimately led to the softening of the ‘heroic’ form of cold hygienic regimen. The first development opened up the public mind; the other appealed to more private sensibilities.

In the new ‘Westernized’ world that was now so closely interconnected by science on both sides of the Atlantic, health advice book publications rose steeply from c.1770 to 1800. Most of them were now written by university-trained medical professionals.45 During the first half of the century, hundreds of university graduate theses had begun to focus on the Hippocratic relationship between human disease and the physical environment, including the social environment. While some were attempting to systematize the classification of diseases through theory, others were empirically searching for disease causus elsewhere. Study of the air had led to study of the climate and ‘emanations’ from foul waters and places, without dislodging earlier theories of direct contagion through touch, bites, or poisons.46 Epidemic quarantine had long been imposed for leprosy and plague, but the full political apparatus of quarantine in Europe is generally held to have emerged with the mercantile plague regulations of the early modern Italian city-states; and for similar commercial reasons, increasingly elaborate pan-European quarantine regulations were gradually adopted during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.47 But the hardest-hitting proofs of environmental impact in the eighteenth century, and which ultimately led to the revision of European quarantine legislation in the nineteenth century, came from the neoclassical revival of military hygiene—the old Roman classical category of ‘ships, camps, and armies’.

The key experiments were those of the Scottish physician Dr John Pringle (1707–82), physician-general of the British Army from 1742 to 1758, who used his position to study the effects of mass crowding on disease and fevers and, especially, the means of ‘antisepsis’ (as elsewhere, Dr James Lind was experimenting with ‘antiscorbutic’ fruit—limes—to stem appalling naval losses due to scurvy). Pringle’s influential Observations on the Diseases of the Army (1752) described how he had applied Sydenham’s cooling regime to his soldiers, and found that it worked, including bathing them in the sea. Mortality fell, and rates of casual infection fell. He also found that a systematic regime of cleanliness was of utmost importance in preserving the gains. His subsequent chemical and mechanical analysis of putrefaction, infection, and contagious particles was also persuasive: ‘It was never imagined, until Dr Pringle shewed it, that the Antiseptic Power is so extensive.’48 Specific antiseptic matter could be found, according to Pringle, in mineral salts and in the fluids of most vegetables, which could be used in the form of good antiseptic odours or fumes (sulphur), or astringent washes (vinegar). More generally, coolness on its own could retard and prevent putrescence: cold water and cold air both had antiseptic properties, but the air was most antiseptic because it also dried. The diseases that responded to hygiene best were the ‘low’ enteric diseases, and diseases of the skin, all of which were prevalent in overcrowded conditions. The remedies were the ancient ones: personal cleanliness and clean clothes, exercise and fresh air, and constant vigilance to eradicate all sources of dirt.

The next generation carried on testing, and took Pringle’s ‘gospel of cleanliness’ into all sorts of places. Captain James Cook used full hygienic principles on board his zealously scrubbed ship, with its equally scoured crew (taking Lind’s fruit with him as an extra onboard experiment) in his first voyage round the globe in 1770, returning triumphantly with only one man lost and all the rest in good health. Other naval officers followed suit, and late eighteenth-century British naval hygiene became a thorough exercise in the health management of men and resources—carrying antiscorbutic oranges, lemons and limes, and fresh vegetables; enforcing drill, swimming, and athletics; cleaning linen and inspecting quarters, and detecting early signs of fevers, all of which revolutionized morale on board ship. By the end of the century the army officers were demanding full-scale hygienic reforms too. The civilian hospital movement was also spurred on by naval hygiene; mainly by Pringle’s reformed naval hospitals, but also by the success of Dr John Haygarth’s antiseptic regime at his fever hospital at Chester in the 1770s—especially his investigations into actively infectious ‘zones’ around the patient (which he concluded was roughly one yard).49 In the 1780s the long campaign to hygienically reform the British and European prison systems began, started by the philanthropist John Howard and the Quaker reformer Elizabeth Fry.

The ‘animal’ nervous system was first clearly described by Albrecht von Haller in 1752, and turned into the central physiological problem of the eighteenth century. By the second half of the century it was widely assumed that ‘nervous’ energy was one of the key agencies through which the human animal interpreted the environment, via the nerves connected to the senses: it was what made humans ‘sensible’—or ‘sensate’, as we would now call it. Moral feeling ran high over potential implications. A whole new nervous pathology was required, and with it a new sensate interpretation of personal hygiene and regimen. As always, excess was blamed. Overwrought nerves, or nervous ‘sensibilities’, were now the cause of a new range of ‘diseases of civilization’—nervous havoc caused by over-sensuous, luxurious, and ‘artificial’ modes of urban life (later called ‘asthenia’).50 In 1780s London, quack ‘sensualist’ doctors adroitly took money off sensitive well-off ‘New Age’ readers whose health interests included the occult, herbalism, primitive diet, balneology, pneumatics, magnetism, and electricity. The medical showman James Graham, ‘the Hygienist’, treated the sexual disorders of the aristocracy on, and in, his famous electric ‘galvanized’ bed (surrounded by flashing lights) in his Electrical Temple of Health and Hymen in London’s fashionable West End. He also guaranteed total cure for nervous prostration from a hectic, overheated social life with other elemental purifications, such as vegetarian foods, water bathing, sun and air bathing—and his unique therapy of earth bathing (being buried up to the neck in earth to absorb its goodness).51 Deep below this urban health faddery, however, lay the many different ‘proofs’ and debates that had originally encouraged Jean-Jacques Rousseau to dream of a new relationship with nature.

Rousseau’s famous Émile, ou, L’Éducation (1762), a health book in the form of a novel, can be credited with the invention of the vis medica naturae at the heart of the Romantic movement. His determination to restore natural medicine sprang, he said, from his own unhappy and confined childhood; and John Locke gave him the physiological framework of nervous and innate sensation that he built on. His concise opinion of nature and nurture was contained in the opening paragraph: ‘The inner growth of our organs and faculties is the education of nature; the use we make of this growth is the education of men; what we gain by our experience of our surroundings is the education of things.’52 Emile and Sophy, his girl partner and ‘helpmeet’, were to be given back all their natural sensations, in full. They were breastfed, never swaddled, lived hardily mainly outdoors, and were allowed to run, jump, shout, laugh, and question freely and instinctively, learning through play—Rousseau’s axiom was that ‘children learn nothing from books that experience cannot teach them’. Even regimen was another of those rigid conventions that bound men hand and foot in society; over-careful habits were artificial, and ‘the only habit the child should be allowed to contract is that of having no habits’. Rousseauian experiments throughout Europe later inspired the Pestalozzian school of educational philosophy, for which Émile was considered to be ‘the children’s charter’.

Rousseau was certainly a wake-up call to newly conscience-stricken mothers in the eighteenth century. The role of the ‘Devoted Mother’ was strengthened: she was a new partner in the education of the child. Old nurses who fussed and fretted and knew nothing of higher scientific, moral, or educational motives were out. Rational mothers, fathers, tutors, and doctors were in:

We write to Reason: Hence ye doating train

Of Midwives and of Nurses ignorant! … Thine is the nursery’s

charge; Important trust ! …

To this then bend thy care, O parent Mind;

Array thy Child in Health. Wouldst thou thy children blest?

The sacred voice of Nature calls thee; Where she points the way,

Tread confident…53

Large numbers of mothers apparently followed Rousseau’s programme to the letter, taking to breastfeeding and vegetarianism along with everything else.54 The French Romantic poet Lamartine, for example, was a vegetarian, having been brought up by a Rousseauian vegetarian mother:

[I had] a philosophical education corrected and softened down by motherly feelings. Physically, this education flowed in a great measure from Pythagoras and Émile. Consequently the greatest simplicity in dress and the most rigorous frugality in food formed its basis … Mother was convinced that killing animals to feed on their flesh was wrong and barbarous, and implanted hard-heartedness.55

Like Émile, she took him to a slaughterhouse at an early age, in order to disgust him (which it did). A whole new generation of Rousseauian-educated children became young men and women in late eighteenth-century Europe, deeply inspired by personal freedom, political liberty, democracy, poetry, science, and a love of ‘sublime’ nature. In England vegetarianism reappeared on the revolutionary agenda at the end of the century, as ‘a necessary step in the moral perfection of humanity’, part of a utopian New Age in which animal rights were to be fully equal with human democratic rights.56 John Oswald’s Jacobin-inspired text The Cry of Nature; or, An Appeal to Mercy and Justice, on Behalf of the Persecuted Animals (1791) stimulated a new group of English vegetarian radicals such as Thomas Young (An Essay on Humanity to Animals, 1798), Joseph Ritson (Essay on Abstinence from Animal Foods as a Moral Duty, 1802), John Frank Newton (The Return to Nature, or, A Defence of the Vegetable Regimen, 1811), and, not least, the hardy and unconventional nature poets enrapturing the London ton at the turn of the century: notably Coleridge (1772–1834), Lord George Byron (1788–1824), and Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822). Shelley was the author of the influential vegetarian essay Vindication of a Natural Diet (1813), the atheistic poem Queen Mab, and the pacifist poem The Revolt of Islam (which influenced George Bernard Shaw and Mahatma Ghandi), all of which made him a famously romantic vegetarian, especially after his early death.57

Thanks to the influence of John Locke, children’s health and medicine (paediatrics) had become a strong clinical speciality in Britain. William Cadogan’s famous Essay upon Nursing, and the Management of Children, which urged natural breastfeeding and was against unnatural swaddling, was published in 1748, some fourteen years before Rousseau; while William Buchan’s Domestic Medicine (1769), written by an enlightened and sensitive Edinburgh children’s doctor, became the best-selling British practical health manual of the second half of the century. Domestic Medicine was translated into many European languages, republished successfully in America, and lasted well into the nineteenth century. If anyone had doubted the importance of a good regimen, or found it difficult to understand medicine, or to talk about their health problems, after 1769 they had their private help and ever-present consultant in Buchan. Buchan and all the other professional authors who wrote in the great surge of health publications in the last thirty years of the century (including, in France, Simon Tissot’s Avis au peuple sur la santé, 1761) were already determined that the hygiene-and-cleanliness message hitherto given to those under parental or state care should reach far into the middling classes, and become a general social habit.

Buchan thought instinctively in public health terms, and in a strongly journalistic style. The first page of Domestic Medicine had a heart-stopper in the second paragraph: ‘It appears from the annual registers of the dead, that almost one half of the children born in Great Britain die under twelve years of age. To many, indeed, this may appear to be a natural evil; but on due examination it will be found to be one of our own creating.’ Buchan combined Rousseauian hygienic sensibilities with brisk, pragmatic common sense, and was yet another Celsus. His elegantly written instructions and discussions on the hygienic vis medicatrix naturae showed him to be a moderate regimenist, a cautious prescriber, and a reluctant bloodletter. Liberal advice on personal cleanliness, good diet, proper sleep patterns, and plenty of exercise sent children out to romp in fresh air away from their books, and kept girls out of tight-fitting stays—‘that wretched custom which prevailed some years ago of squeezing every girl into as small a size in the middle as possible’. Menstruation was approached hygienically and practically, banishing secrecy, urging cleanliness, good diet, and exercise; he even talked openly about the menopause, calling it a difficult and dangerous period of life: ‘Hence it comes to pass, that so many women either fall into chronic disorders, or die about this time’; continuing, a little more reassuringly, ‘Such of them as survive it, however, often become more healthy and hardy than they were before, and enjoy strength and vigour to a very great age.’58

Three special chapters on ‘Intemperance’, ‘Cleanliness’, and ‘Infection’ enlarged on three themes dear to Edinburgh medicine: Buchan reverently visited and interviewed the ageing Sir John Pringle, and enshrined his theories throughout Domestic Medicine. Human slovenliness and ignorance were the main culprits behind disease: ‘the peasants in most countries seem to hold cleanliness in a sort of contempt … everybody may be clean, even in rags, or in the meanest abode’. Of streets and towns: ‘We are sorry to say, that the importance of cleanliness does not seem to be sufficiently understood by the magistrates of most great towns in Britain; though health, pleasure, and delicacy, all conspire to recommend it.’ In true patrician style, the all-important question of urban water supply that was to feature so largely in the nineteenth century was politely mentioned, while the idle poor were crushingly accused:

Most great towns in Britain are so situated as to be easily supplied with water; and those persons who will not make a proper use of it after it is brought to their hand, certainly deserve to be severely punished… It is not sufficient that I be clean myself, while the want of it in my neighbour affects my health as well as his. If dirty people cannot be removed as a common nuisance, they ought at least to be avoided as infectious. All who regard their health should keep a distance even from their habitations.

But the Buchanite poor were to have good done unto them, whether they liked it or not. Buchan regarded nursing as a Christian mission:

There cannot be a more noble, or more god-like action, than to minister to the wants of our fellow creatures in distress … to instil into their minds some just ideas of the importance of proper food, fresh air, cleanliness, and other pieces of regimen necessary in diseases, would be a work of great merit, and productive of many happy consequences.

This was a direct appeal from the pious Nonconformist Buchan to the many thousands of godly women and men with time on their hands and zeal in their hearts, and certainly helped to educate and support the generation of social reformers who became active towards the end of the century. Buchan ended his chapter on cleanliness with a rousing (and very much quoted) appeal to enlightened civility and common sense:

Cleanliness is certainly agreeable to our nature … It sooner attracts our regard than finery itself, and often gains esteem where that fails. It is an ornament to the highest as well as the lowest in station, and cannot be dispensed with in either. Few virtues are of more importance than general cleanliness. It ought to be carefully cultivated everywhere; but in populous cities it should be almost revered.59

After 1789 the French Revolution gave hygiene a new political status. Revolutionary French hygienists enthusiastically followed the plan of rational medicine set by the philosophes, and used hygiene and preventive medicine as a stick with which to beat the forces of conservatism. Revolutionary hygiene progressed from being a lengthy article in the Encyclopédie méthodique in the 1780s to becoming officially adopted as one of the rights of the healthy citizen, and one of the duties of the state, by the National Convention’s Committee on Salubrity in 1793. Behind the scenes public hygiene had been a long time maturing. Plague deaths (and commercial life insurance tables) had stimulated the first studies of ‘political arithmetic’ in seventeenth-century England, and a similar trend towards population quantification emerged in the pious economic ‘cameralism’, or benevolent despotism, of the early eighteenth-century Protestant German states, who began to devise pious political policies (medical police) to encourage ‘vigorous growth …virtuous conduct… praiseworthy education … [and] abundance of necessary, useful and superfluous means of life’ for their populations.

In 1732 Peter Sussmilch produced the first demographic study using population statistics; in 1738 Friedrich Hoffman published Medicus Politicus (‘The State Doctor’); in 1749 first Sweden and then Finland completed the first European censuses, which formed the basis of their early and comprehensive national health systems, and the rest of Europe followed during the course of the century. At the time of the French Revolution, Johann-Peter Frank was halfway through his six-volume System einer vollständigen medizinischen Polizei (‘A System of Complete Medical Police’, 1779–1821), which was to form the basis of a newly established public health university course for trainee Habsburg imperial administrators. In it he discussed the hygienic necessity for the public regulation of marriage, pregnancy, and lying-in services, personal hygiene, clothing, nutrition, food control, drainage, pure water supplies, street cleaning, venereal disease, prostitution, orphans, housing, and the sanitary regulations of hospitals. Frank became the hero of the partie d’hygiène in France, based at the new Department of Hygiene at the Royal Academy of Medicine, which put French hygiene on a solidly professional footing after the Napoleonic Wars.60

But at the heart of European hygiene in the revolutionary period c.1790–1820 was a ‘transcendent’ or ‘vitalist’ Naturphilosophie that galvanized the natural sciences and inspired the Romantic concept of ‘sublime nature’. German Naturphilosophie—nature philosophy—laid the foundations of nineteenth-century eugenics and naturopathy, and (incidentally) finally legitimized the warm bath. Vitalism was the old seventeenth-century scientific philosophy that argued for the material existence of the divine or supernatural, against the prevailing Cartesian, or mechanistic, scientific paradigm; and in the eighteenth century it had become deeply engaged with the contemporary discoveries of ‘universal forces’ in physics (such as chemistry, pneumatics, electricity, and magnetism). Vitalism was reinvigorated by the philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), a fervent admirer of Rousseau, in his seminal work, the Critique of Pure Reason (1781). Kant seemed to provide a rational solution to the problem of material-immaterial existence by defining ‘pure reason’ (or pure science) as a priori: pure reason was not contingent, it existed of itself, and was ‘absolute’ in itself, like pure mathematics or logic, and humans used natural rationalism and intuition to comprehend a priori truths about the invisible forces of the universe (which Kant saw as consisting of eternal motions of attraction and repulsion). Many of Kant’s followers (including the philosopher Hegel and the great physical geographer Alexander von Humboldt, who wrote a massive five-volume work on the integrated ecology of the cosmos) therefore dedicated their lives to the rational progress of a priori knowledge in the modern era; or (like the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, or the painter Joseph Turner) found inspiration in ‘sublime’ visions of nature.

The most speculative form of pure Naturphilosophie, however, was developed by Friedrich Schelling in his System of Transcendental Idealism (1800), which involved devising a complete theoretical model of the synthetic macrobiological universe, infused with the ‘pure spirit of nature’, governed by harmonious principles of logic and universal polarities (‘antinomies’)—often demonstrated by followers in the form of complex tables, diagrams, and flow charts.61 Transcendental Naturphilosophie saw the whole world as an endless cycle of matter, or, as one health book author put it,

we find [Nature] moves in a circle; that the smallest particle, though invisible to our eyes, is usefully employed by her restless activity; and that death itself, or the destruction of forms and figures, is no more than a careful decomposition, and a designed regeneration of individual parts, in order to produce new substances, in a manner no less skilful than surprising… all Nature is united by indissoluble ties, [hence] we justly conclude, that man himself is not an insulated being, but that he is a necessary link in the great chain which connects the universe.62

Subsequently airbrushed out of materialist history, ‘pure reason’ Naturphilosophie became an almost forgotten scientific episode until the more complex questions it raised concerning holistic, balanced, or ‘organized’ systems quietly re-emerged in early twentieth-century biology.63 But its vitalist health practices and nature philosophies lived on; for the spiritual and philosophical holism that so disgusted the nineteenth-century professional materialists had a much greater and more long-lasting appeal for lay men and women.

The medical bible of the end-of-century European Naturphilosophie vitalists was the health book by Goethe’s friend Christian Wilhelm Hufeland (1762–1836), called Makrobiotik, oder, Die Kunst, das menschliche Leben zu Verlängern (1794), translated into English as The Art of Prolonging Life in 1797 (thus taking the strange foreign word Makrobiotik out of the title).64 Makrobiotik was a handbook on how to control the ‘rapid or slow vital consumption’ of the life force, and how to regulate the ‘vital operations’ and ‘vital organization’ of the body. It held out the hope not only of personally prolonging life, but of being able to perfect it universally, in the future, through physical culture: ‘by culture alone, [man] becomes even physically perfect … physical and moral health are as nearly related as body and soul. They flow from the same sources; become blended together; and when united, the result is, HUMAN NATURE ENNOBLED AND RAISED TO PERFECTION.’65 There was a new emphasis, in vitalist health care, on what we might call the regimen of future genetics—the guiding and regulation of the conditions of birth as well as life. Hufeland’s basic ‘Means of Prolonging Life’, for example, started with: ‘Good physical descent’. The British vitalist author A. F. M. Willich spelt out these ‘Means’ more clearly:

A certain bodily and mental disposition to longevity. A sort of hereditary disposition. A perfect birth of child, and proper conduct in the mother. A gradual culture of the physical and mental faculties. A constant habit of brooking and resisting the various impressions of external agency. A steady and equal progress of life. A sound state of digestion. Equanimity of mind—avoiding violent exertions.

In the highly symmetrical style of vitalist physiology, the exact opposite regimen, of course, spelt doom:

Bad descent, debilitating education, impure air, bad nourishment, sedentary mode of life, immoderate or deficient sleep, immoderate activity, care of skin neglected, passions and excessive sensibility, venereal dissipation, pain, unnecessary and superfluous use of medicines, poisons, infectious poisons …

The vitalists were constantly lamenting the loss of ‘national debility—the debility of the age’ in which man was ‘no longer the son of nature’ and ‘nothing remains except affected sensations’. The poor had ‘immoral habits and relaxed principles’, while the upper classes were cultivated but supine. ‘I hope I may be forgiven’, said Willich, ‘when I assert that the present age appears to labour under a certain mental and corporeal imbecility.’66

The vitalists were great enthusiasts for all types of bath, cold, warm, and hot—especially the new vapour baths and shower-baths. The science of dermatology was riding high at the turn of the century, as a newly revived subspecialism of physiology focused on the still-virulent skin diseases of the poor. Through vitalist dermatology the warm bath at last reappeared in public, medically reinstated in full.67 The skin, readers were now told, was one of the most important organs of the body: ‘the greatest medium for purifying our bodies’—‘the seat of feeling, the most general of all our senses, or that which in an essential manner connects us with surrounding nature’. Willich even pointed out the natural connection between human and animal grooming.68 He gave the warm bath an unqualified seal of approval, in the now standard chapter ‘Cleanliness in General’:

Cleanliness … claims our attention in every place which we occupy, and wherein we breathe … Let the body, and particularly the joints, be frequently washed with pure water… The face, neck and hands … the ears … the whole head … the mouth … the nose… the tongue… the feet… the beard and nails …it would be of great service, if the use of baths were more general and frequent, and this beneficial practice not confined to particular places or seasons, as a mere matter of fashion. Considered as a species of domestic remedy, as one which forms the basis of cleanliness, bathing, in its different forms, may be pronounced one of the most extensive and beneficial restorers of health… The warm, that is the tepid, or luke-warm state, being about the temperature of blood, between 96 and 93 of Fahrenheit, has usually been considered as apt to weaken and relax the body; but this is certainly an ill-founded notion …On the contrary, the lukewarm or tepid bath from 85 to 96 is always safe; and so far from relaxing the tone of the solids it may be justly considered as one of the most powerful and universal restoratives with which we are acquainted.

15 An early nineteenth-century neoclassical nude with a classical hairstyle and a crystal bath—but the lion-head taps are attached to a modern hot-and-cold plumbing system.

Children should be washed in warm water daily, adults once a week, ‘and it will be of considerable service to add to it three or four ounces of soap’. Precisely accurate temperatures were essential in maintaining exactly the right mean body temperature, along a supposed sliding scale of nervous or ‘sthenic’ irritability (hence the new diagnosis of ‘asthenia’). The ‘vital signs’ of the human body were also thought to react to air temperature, barometric pressure, and air quality, which led some vitalists to start experimenting with the improvement of domestic ventilation, and even with outdoor air baths: ‘By exposing the naked body for a short time to an agreeable cool or even cold air, we perceive effects somewhat similar to those produced by the cold bath…[It is] a species of bath that certainly deserves a fair trial.’69

With such high standards, the general public’s personal hygiene was inevitably assessed and found wanting: ‘among the greater part of men, the pores of the skin are half-closed and unfit for use’. Virtually all commentators were now agreed that the general levels of personal cleanliness among the ‘mass of the people’ were unacceptably low; and together with the clinical dermatologists, vitalist doctors reopened the debate on public baths.70 In an unmistakable reference to German traditions of stoving, both Willich and Hufeland called for re-establishment of public warm baths, ‘that poor people might enjoy this benefit, and thereby be rendered strong and sound, as was the case some centuries ago’. But in the absence of public hot baths, most people had to tackle these problems on their own; and even the middle-class Drinker family in America found increased bathing and washing an educational challenge, as they took up each successive craze. Henry and the children swam in outdoor public locations in the 1770s and 1780s; and in 1798 they bought a new ‘shower box’ for the back yard (eliciting Elizabeth’s comment: ‘I bore it better than I expected, not having been wett all over at once, for 28 years past’). Then came the ‘portable bath’ in 1803, which could be used with warm water, indoors. This was an instant success: ‘It is very good I believe for young and old,’ announced Elizabeth, and from then on the family used it constantly.71 It would seem that the respectable reappearance of the domestic warm bath was greeted with great relief by the middling classes, especially those who were neither young nor fit, and was the obvious solution to all their personal cleanliness problems. All that remained in the nineteenth century was to extend these benefits to the lower classes.

From c.1500 onwards public health education had transmuted and transmitted successive waves of thought and eloquence—humanism, puritanism, neoclassicism, romanticism—catching many people in its wake. The eighteenth-century Enlightenment, however, had produced a public health education movement and a gospel of cleanliness and hygiene that still only really affected the middling and aristocratic groups in society. Radical hygienists knew that the next stage was to reach the poor ‘in every one of our considerable towns’. In Hygëia: or, Essays Moral and Medical (1802) the democrat and experimenter Dr Thomas Beddoes stated:

It should now be possible to provide each individual with a set of ideas, exhibiting how the precise relation in which his system, and the several organs of which it is compounded, stand to external agents … and that these set of ideas be so placed in his head, that he may refer to them with as little difficulty as to the watch he wears in his pocket.72

A little optimistic perhaps. Possibly the simplest and original Regimen Sanitatis Salerni had provided just that, once upon a time. Instead a nascent public health and hygiene movement evolved into a general ‘sanitarian’ movement during the course of the next century, working pragmatically towards the goal of a complete medical police or ‘welfare state’, while most of the population were still absorbing the personal hygiene lessons of the previous century.