DIGGING DEEPER 3

HOW OLD IS THIS AND WHY IS IT PRESERVED?

A journalist once asked me during an interview, “All of what you excavate, study, and write about took place so long ago. How can you be so certain of your dates?” My short answer to him was “radiocarbon, Egyptian texts and other written records, synchronisms, dendrochronology, pottery typology, a plus/minus factor, and a willingness to acknowledge that none of it is fixed in stone.” I was a bit surprised at his question, which was asked in a rather aggressive manner, but then it occurred to me that maybe this is something that a lot of other people wonder about as well but are afraid to ask.

In fact, one of the questions that I am asked most often at dinner parties and other social gatherings is simply a variation of the question that the journalist asked me: “How do you know how old your finds are?” People also want to know how it is possible that things which are so old are still preserved. “Why haven’t they crumbled to dust?” they ask. So here, let’s address the topics of how archaeologists date ancient artifacts and what kinds of conditions it takes for such things to be preserved.1

The first question is probably the easiest to answer: How do we know how old something is? As I said to the journalist, it can be as simple as reading an Egyptian text, especially if it says something like “year 8” of a particular pharaoh’s reign and we know from other sources what the dates of his rule were. Other times we have synchronisms between cultures or civilizations that interacted, so that we know, for example, from a letter found in the Amarna archive in Egypt that Amenhotep III lived at the same time as Tushratta of the kingdom of Mitanni (in northern Syria) because they were writing letters back and forth … and we know from other evidence that Amenhotep lived during the early fourteenth century BCE, so Tushratta must have as well. And in that manner, we can often put together chronological lists of rulers, events, and so on, often using the king lists and astronomical observations left to us by the ancient peoples themselves in Babylonia, Egypt, Assyria, and elsewhere.

A variety of scientific dating methods are also now available to the archaeologist. Common methods used to date ancient objects are radiocarbon dating, thermoluminescence, and potassium-argon analysis.2 They are what we use to determine the “absolute date” of an object—in other words, its date in calendar years, like 2015 CE or 1350 BCE, as mentioned in a previous chapter. It’s not always possible to do this, and so sometimes we have to settle for a relative date—for example, saying that Level 3 lies below Level 2 at the site and is therefore older. The archaeologist might not yet know the absolute date for either level, especially at an early stage in the excavations, but he or she already knows where they are relative to each other.

Probably the most commonly used dating method is radiocarbon dating, otherwise known as carbon-14 dating (C-14 for short).3 This, like all the chemical methods, has a “plus-minus” factor, as in “1450 BCE plus or minus twenty years,” and a statistical probability that the date will fall into the suggested range. Because of this, C-14 dating isn’t particularly useful for relatively recent items, but it is good for dating objects that are at least several hundred years old; several thousand years is even better.

The basic idea, discovered by a scientist named Willard Libby who won a Nobel Prize for his work, is that all living things ingest, either through breathing or through eating, a small amount of a radioactive isotope of carbon while they are alive, along with all the normal carbon. C-14 is constantly being created from radiation in the atmosphere. It combines with oxygen to form a radioactive version of carbon dioxide.

Plants incorporate this C-14 into their system during photosynthesis; animals and humans then ingest it by eating the plants. Since it is radioactive, C-14 decays, as do all radioactive materials. It has a known half-life of a bit more than 5,700 years—that is, half of the original amount will have decayed and disappeared in a bit more than 5,700 years. Since it is fairly easy to determine how much carbon would have originally been in a particular sample, and since the ratio of C-14 atoms to normal C-12 atoms is fairly constant, one can measure the amount of C-14 that is still left in a sample and thereby figure out the date when that organism died (in the case of a human or animal) or was chopped down (in the case of a tree that became a piece of wood) or otherwise ceased to exist (as in short-lived plants and weeds).4

Organic materials like human skeletons, animal bones, pieces of wood, and burnt seeds can be C-14-dated. Burnt seeds are especially good, because they usually had a very short shelf life before essentially ceasing to exist. Similarly, short-lived brushwood is good.5 Radiocarbon dating is relatively cheap to do, at least compared to other dating procedures.

The technique can’t be used to directly date stone tools or pottery, since those items never ingested C-14. It can, however, be used to date organic items that might have been found in the same context as such stone tools or pottery, thereby helping to date stone and pottery by association.

There are also some known difficulties and problems associated with the technique, including the fact that it requires the destruction of at least part of the object in order to sample it, and that the amount of C-14 in the atmosphere has not always been constant but has fluctuated. Calibration curves accounting for such fluctuations have been created, as have other means of correction, and so radiocarbon dating has been one of the most frequently used methods to date ancient sites. We use it at both Kabri and Megiddo, the sites where I have worked most recently.6

In addition, if a large fragment of wood is discovered, like a beam that was once used in a ceiling or wall or even as part of a ship, another technique can be applied besides C-14 dating. This is dendrochronology, or tree-ring dating, which involves counting the rings that can be seen in the wood.7 This technique may be familiar to those who have visited places like Yosemite or Sequoia National Park, where often a very large stump of a tree is on display, with little markers attached to some of the rings, saying things like “1620: Pilgrims land at Plymouth Rock” and “1861: Start of the Civil War.” The rings in those trees have been interpreted in terms of a master sequence that has been constructed painstakingly by scientists over the years. If a piece of wood with visible rings is discovered during an excavation, it is sometimes possible to fit it into such a sequence and determine its probable date, but even such master sequences do not extend back in time more than ten thousand or twelve thousand years.

The same basic principles can be used to date other materials with various chemical methods, if the age of the site being excavated is appropriate for them. For instance, when one is trying to date a stone tool from Olduvai Gorge in Africa, which is a crucial site for understanding human origins, potassium-argon dating can be useful. This method measures the difference between the amount of potassium in the rock and the amount of argon in it, because potassium decays and becomes argon over time. But it takes a very long time for the decay to happen, and so this method is best used when something is between two hundred thousand and five million years old. In such cases, it would be impossible to use radiocarbon dating, which works on organic remains but not stone tools and is useful only for dating things within the last fifty thousand years.

Thermoluminescence might be used on certain objects found at “younger” sites. This technique can determine the absolute age of something made from clay, like a storage pot, by measuring the amount of electromagnetic or ionizing radiation still in it. Specifically, it can indicate how long it has been since the object was baked or fired in a kiln. Researchers have found that the object has to have been heated up above 450 degrees centigrade or the technique won’t work.

A similar, but newer and still experimental, method is rehydroxylation, which measures the amount of water in a piece of pottery. I first heard about it in 2010, at a miniconference held at Megiddo during our summer excavations that year, and I thought it was a really interesting—and promising—procedure. It seems that when a piece of pottery is fired in a kiln, all the water in the clay evaporates during the process. As soon as the piece of pottery is taken out of the kiln and cools off, it begins to absorb water from the atmosphere again at a constant, slow rate, regardless of the vessel’s environment.8 Thus, by measuring the amount of water in a sherd, we can determine the last time that it was fired … and thus probably its age.

There can be problems with measuring rehydroxylation. We were told about how the original researchers were given a medieval brick from Canterbury; when they tried this method on it, repeatedly, the rehydroxylation analysis dated the brick as only about sixty-six years old, although they knew it had to be much older than that. It eventually turned out that the brick had been in an area of Canterbury that had been bombed during World War II and was caught in the ensuing incendiary fire. The fire had reset the water content of the brick back to zero as of the 1940s, and so the dating method clearly worked, but it no longer measured the date of the brick’s original firing back in the medieval period.9

It is possible to do something similar with a piece of obsidian, a technique called obsidian hydration. Obsidian is volcanic glass that was highly prized in antiquity for its sharpness and in fact is still used in some surgical scalpels today. It also absorbs water at a constant and well-defined rate once it is exposed to air, and so measuring the amount of water in a particular piece of obsidian can be used to date obsidian tools.

Stratigraphy, pottery seriation, and object association can also all be used as relative dating methods, especially if it is not possible to generate a precise absolute date otherwise. We have discussed all these in a previous chapter, and so here it is simply worth remembering that one way to date something can be as simple as seeing what was found with it—in other words, in association with it or in the same context, like a stone tool found with a datable organic object.

For example, if an excavator finds a coin minted by the Roman emperor Vespasian in a grave, clearly the grave cannot date from before Vespasian’s time. Thus everything in the grave along with the coin should be from about the same period, unless it was an heirloom at the time that it was buried, which does happen. Similarly, if an Egyptian scarab with the cartouche of the pharaoh Amenhotep III is found on the floor of the room in an ancient house or palace that is being excavated, then everything else on the floor probably dates to the fourteenth century BCE, when Amenhotep III was ruling Egypt.

At Tel Kabri, for instance, on the floor of one of our rooms in the palace, we found a type of scarab that dates specifically to the Hyksos period, that is, the seventeenth to sixteenth century BCE. This gave us an indication of the date for that room, which was then confirmed by the radiocarbon dates that we got from some of the charcoal samples that we submitted for analysis.

At the Uluburun shipwreck, found off the coast of Turkey in 1982 and excavated for the next fourteen years, the excavators were able to use no fewer than four techniques to date the ship: radiocarbon dating, dendrochronology, the type of Minoan and Mycenaean pottery on board, and the fact that they found a scarab of Nefertiti. All these combined to point to a relative date in the Late Bronze Age and an absolute date of about 1300 BCE for the time that the boat sank.10 Each dating method has its own limitations and uncertainties, and so when four separate methods point to the same approximate date, the archaeologist can offer that date with a great degree of certainty.

The other questions are a bit more complicated to answer—“How can things that old still be preserved? Why haven’t they crumbled to dust?” The answer is that a lot of ancient things have crumbled to dust or have been otherwise destroyed and have not been preserved. In fact, only a small percentage of what once existed has survived to the present. Inorganic materials like stone and metal frequently survive, though silver will turn purple in the ground, bronze will turn green, and so on. It’s only gold that stays the exact same color. I’ve found gold only a few times in my career, but I’ve found a lot of bronze, which is probably to be expected since my particular period of interest is the Late Bronze Age.

Other items that are made of organic or perishable goods are not as durable, and it can be rare to find things like textiles or leather sandals at most archaeological sites. Happily, though, sometimes such items, and human bodies, are preserved. Usually this happens in conditions of moisture and temperature extremes—in other words, places that are very dry, very cold, very wet, or without oxygen.11 A few interesting examples from each such location can be readily discussed.

For example, perishable objects have survived in the very dry conditions within King Tut’s tomb in Egypt, where all the wooden furniture and boxes and chariots were found still completely intact. The wooden boats buried near the pyramids have survived for the same reason, as have so many mummy coffins and pieces of papyrus from ancient Egypt.

Other mummies preserved by dry conditions in a desert come from much farther away, in China. These, some as much as four thousand years old, were first reported to the rest of the world by a professor of Chinese studies at the University of Pennsylvania named Victor Mair. He spotted them in a museum in the city of Ürümqi, in a remote part of China north of Tibet, known as the Tarim Basin. He began to study them, as did Professor Elizabeth Barber of Occidental College in California. Mair and Barber have both published books about the mummies, which were extremely well preserved because of the very dry conditions of the desert environment where they were buried.12

What is unique about some of the mummies is that, even though they are found in China, they have Causcasoid or European features, including brown hair and long noses. They were buried with textiles and cloth that looks a lot like plaid. Furthermore, their DNA suggests that they may be of western origin, with links to Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, and possibly even Europe.13

Studies of these mummies are still ongoing, but perhaps we should not be particularly surprised by these initial findings. The Silk Route, which connected China in the east to the Mediterranean in the west from the second century BCE on, is known to have run through the Tarim Basin. In fact some of the mummies were brought to the United States in 2010, as part of a traveling exhibition on the Silk Route.14

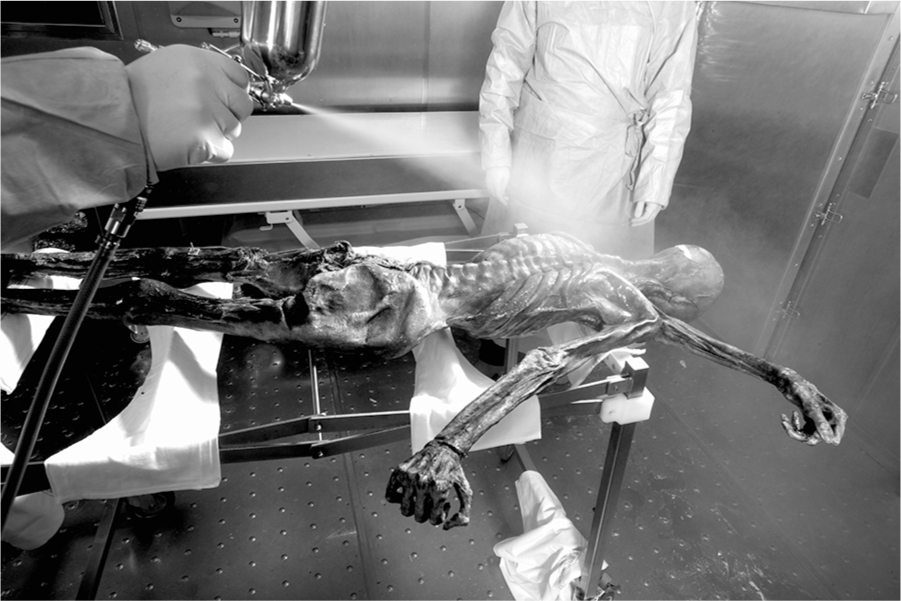

In contrast, the bodies of Ötzi the Iceman, the Siberian Princess, and Juanita the Ice Maiden, discovered in 1991, 1993, and 1995, respectively, were all found preserved in extremely cold conditions. Ötzi especially has been the subject of much analysis and discussion since he was accidentally discovered by hikers in the Alps, on the border between Austria and Italy.15 He spawned a worldwide craze, especially in the region where he was found, where one can now purchase Ötzi wine, Ötzi chocolate (think chocolate Easter bunnies, but in the shape of Ötzi), and, perhaps most relevant of all, Ötzi ice cream.

At first it was thought that Ötzi was a recent murder victim, and so the police were called in. This was most definitely a cold case, though, since not only was Ötzi encased in ice, but it turns out that he had been lying there for more than five thousand years. In fact, it now looks as though Ötzi died in about 3200 BCE, which is more than six hundred years before the pyramids in Egypt were built.16

FIG. 13. Ötzi the Iceman, after discovery (photo by Robert Clark, courtesy of National Geographic)

Ötzi’s body lay wedged in a hollow formed by some rocks. A glacier creeping down the slope swept right over the rocks and his body, so that he was preserved under many feet of ice and snow for thousands of years. In 1991, a sandstorm in faraway North Africa sent sand up into the atmosphere that eventually settled on the ice above Ötzi. The sand, absorbing the sun’s rays, melted the ice and exposed Ötzi’s head, shoulders, and upper body.

The police, unaware that this was an ancient body, hacked Ötzi out of the ice, damaging his body as well as his belongings, which were scattered around him. Once scientists realized this was not a modern-day wayward hiker but far more ancient, scientific archaeological excavations were carried out in 1992. These retrieved additional artifacts, including his bearskin cap. Ever since then, detailed studies have been made of Ötzi and his belongings, including a complete workup of his DNA.

It turned out that Ötzi had indeed been murdered, as the police who were called to the scene had first thought, though the killing had taken place several thousand years earlier. It was ten years before murder could be proven, but the evidence was eventually quite obvious. Though it hadn’t been noticed before, in 2001 an alert radiologist examining X-rays and CT scans that had been taken of Ötzi saw a foreign object embedded in his back, just below his left shoulder. It turned out to be an arrowhead, with a corresponding entry wound several inches below, which means that whoever shot him was standing below Ötzi and shooting upward.17

It was subsequently determined that the arrowhead had severed an artery, meaning that Ötzi had probably bled to death. It also means that he was shot in the back, which implies murder rather than an accident. The fact that he has a defensive cut on his hand as well indicates that some sort of fight had taken place, and that he may have been fleeing from the battle when he was fatally shot.18

However, as mentioned, Ötzi is not the only ancient person to have been found on ice. In 1993, a mummified body known as the Siberian Princess or Ice Maiden was found on the Ukok Plateau in southern Siberia, near the border with China. Dating to the fifth century BCE, she was about twenty-five years old when she died, perhaps from breast cancer. She was buried with six horses, all saddled and bridled, probably meant to accompany her into the afterlife. This perhaps makes a great deal of sense, because it is thought that the princess was a member of the Pazyryk people—a nomadic group described by the Greek historian Herodotus in the fifth century BCE—who spent most of their lives on horseback.19

She is also known for her numerous tattoos. These, primarily on her left shoulder and arm, include a mythological animal, which looks like a deer with a griffin’s head and antlers that also have griffin’s heads at the ends. Other bodies buried nearby, of men identified as warriors—some of whom were dug up decades earlier—have similar tattoos; one has them on both arms, his back, and his lower leg.20

Two years later, in 1995, anthropologist Johan Reinhard found a mummy of a twelve- to fourteen-year-old Inca female on Mount Ampato in Peru. She too is occasionally called the Ice Maiden, but since that causes confusion with the mummy from Siberia, more usually she is simply Juanita.21

Reinhard found her near the peak of the mountain, at a height of more than six thousand meters (eighteen thousand feet) above sea level, where she had been buried more than five hundred years ago. He had climbed the mountain to photograph a nearby volcano that was erupting, thinking he could get a good picture from that vantage point. It didn’t seem to be a likely place for an Inca sacrifice, and yet there she was, exposed to the elements because the ash from the volcano had melted some of the ice that had protected her. In his book The Ice Maiden, Reinhard describes carrying her down the mountain in his backpack: she weighed only eighty pounds.22

She is not the only such Inca mummy. Others include two more that Reinhard also found on Mount Ampato, a boy and a girl located a thousand feet below the summit, when he returned with a full team to explore the mountain systematically. One television show, broadcast by PBS, estimated that there may be hundreds more such Inca children encased in what are now ice tombs on top of peaks in the Andes, where more than 115 Inca sacred ceremonial sites have been found.23 The question of who these children were and why they were left to die on mountaintops still engages anthropologists and archaeologists working in the region today.

As for finding objects and bodies that have been preserved in waterlogged conditions, a small wooden writing tablet that dates back to the eighth century BCE was found submerged in a well at the site of Nimrud in Iraq. Pieces of two more were found in the Uluburun shipwreck, where they had been preserved 140–70 feet below the surface of the Mediterranean Sea for more than three thousand years. However, it is the so-called bog bodies, which have been found in places like Denmark and England, that are among the best-known examples of organic material to have been preserved in a waterlogged environment.

These bog bodies have been so well preserved that it is possible to see individual whiskers in a beard and the strands of the rope around a victim’s neck. Several hundred such bodies have been uncovered in a variety of places in England and Europe within once-swampy areas, called bogs or fens.24 Bogs contain peat: a deposit of dead and decayed plant material, usually moss. Peat can be used as fuel or as insulation on cottage roofs. The workers who dig in these bogs occasionally find human remains, of which the soft tissues have been almost completely preserved because of the acidic conditions and the lack of oxygen in the bogs, even though the bones themselves are long gone.

FIG. 14. Tollund Man (photo by Robert Clark, courtesy of National Geographic)

One such body, known as Lindow Man, was found in northwestern England in 1984, in the Lindow Moss bog.25 The autopsy indicates that he was about twenty-five years old when he died. He had been hit twice on the head with a heavy object, then strangled with a thin cord, which also broke his neck, and finally had his throat cut for good measure. It is not clear whether he was murdered or ritually sacrificed. This is definitely what we would consider a cold case, because he was killed about two thousand years ago, sometime during the first or early second century CE.

A similarly preserved body was found in 1950 by two workers cutting peat in a bog in Denmark, not far from the town of Silkeborg. Known as the Tollund Man, he dates to the fourth century BCE, and so he is about five hundred years older than Lindow Man. In his case, we can see every detail of the leather cap that is still on his head and the belt around his waist, as well as the stubble on his face and the rope around his neck that was used to hang him.26

The two workers who found him thought that he was a murder victim, and he may well have been, but his death occurred nearly twenty-five hundred years ago, and it is unclear why he was killed. He was probably about forty years old at the time of his death.

As for examples of artifacts and bodies preserved in areas with little or no oxygen, obviously such places are pretty rare in the world, but they do exist—for instance, deep in the Black Sea, below two hundred meters (650 feet), where the water is very still and oxygen doesn’t circulate to the bottom.27 Since there’s no oxygen, there’s no reason for anything to disintegrate, because there’s nothing alive there even at the microscopic level that could damage the artifacts. This is why Bob Ballard found amazing things when he sent a remotely operated vehicle down into the depths of the Black Sea in 1999 and again in 2007.28

Ballard may be best known as the discoverer of the Titanic, but in archaeology he is perhaps better known for his discoveries in the Black Sea. He found a Neolithic settlement, an ancient shoreline, and a beach that are now far below the surface of the sea—meaning that the whole area probably flooded sometime in antiquity; two Columbia University professors suggest that such a cataclysmic event may have taken place about seventy-five hundred years ago, around 5500 BCE. Ballard has also found several shipwrecks from the Roman and Byzantine periods, dating from between one thousand and fifteen hundred or more years ago. In at least one of them, the wood of the boat is so well preserved that the tool marks of the original shipbuilders on the individual pieces of wood are still visible. And one of the jars that they brought up had the original beeswax still sealing the top closed.29

Not all ships have been as well preserved as the one that Ballard found in the Black Sea or the Egyptian ships near the pyramids. Other ships have left only their imprints in the soil. Their poor state of preservation is far more typical of artifacts that have been found simply buried in the earth rather than in extreme environmental conditions, but these examples also show how even those badly preserved remains can be interpreted by savvy archaeologists working from the pattern of what has been left behind.

Take, for instance, the Sutton Hoo ship in Suffolk, England. It is twenty-seven meters long and was found in 1939 by an archaeologist named Basil Brown. The owner of the property had invited Brown to excavate a large mound, one of many on her land, in southeastern England. Within the mound, he found the remains of this ship.30

The ship, which is of interest for many reasons, probably dates to sometime between 620 and 650 CE.31 This was during the Anglo-Saxon period, which began about 450 CE—after the end of Roman occupation, when new immigrants arrived from continental Europe—and lasted until the Norman Conquest in 1066 CE.

Perhaps most interesting is that the ship isn’t actually there anymore, and yet its components can still be seen perfectly well: although the wood of the ship is completely gone, it is very clear where it once was. The dirt had stains where the wood has disintegrated; there are raised ridges in the soil running the width of the ship, spaced just a few feet apart for its entire length; and there are rusted iron nails that once held the pieces of wood together.32 What Brown discovered is the shadow of the boat, rather than the boat itself.

So why bury a boat on land? Most archaeologists think that the boat was buried with its owner; that is, it served as a final resting place for a warrior, or a king, or some other notable deserving of such an honor. But no remains of the body have been found in the boat or anywhere near it. That seems strange: If this was a burial, where is the body? One possibility is that the body and the bones have decomposed so much that they have simply vanished, just like the wood of the ship.33 If so, they left no mark at all. That’s the scenario that most people believe.

Another possibility is that there never was a body. If that’s the case, then this is what is known as a cenotaph—that is, a monument to someone who is buried elsewhere. A lot of war monuments today are basically cenotaphs, and it might be that the Sutton Hoo ship is an ancient war monument—perhaps a commemoration of a battle fought by the Anglo-Saxons in this part of England.34

But even though it didn’t yield a body, the Sutton Hoo ship proved to be a treasure trove in other respects. The center of the boat held a number of objects: shoulder clasps made of gold and with enamel inlays, which were probably attached to a cloth tunic or shirt that has perished; a solid gold belt buckle with an intricate design and a metal lid with enamel inlays, which is all that remains of what was once probably a purse, with the cloth or leather part now gone; and drinking horns inlaid with fancy designs. These artifacts again indicate that this is no ordinary burial; one can only imagine the celebrations at which they were once used.35

FIG. 15. Iron helmet from Sutton Hoo (courtesy of the British Museum)

Among the objects that have stirred the most interest is an iron helmet, complete with a faceplate with holes for the eyes and both a nose and a mouth made of metal.36 Parts of it are overlaid with decorative gold. It must have been very expensive back in the day and probably belonged to someone either wealthy or powerful or both.

In 2011 a similar discovery of a phantom ship was made on the western coast of Scotland, on the Ardnamurchan Peninsula. Here, in a burial that dates to the tenth century CE, is what appears to be a Viking warrior buried in his boat.37 At that time, this region was located along a primary north–south sea route between Ireland and Norway, and Viking houses have been found on the nearby Hebrides Islands.

The grave is five feet wide and about seventeen feet long, which is just large enough to hold the entire boat. As with the Sutton Hoo boat, the wood of this boat has decayed and is now completely missing, apart from a few remnants here and there. Again, the archaeologists found the iron rivets that had once held the boat together—about two hundred of them—and they could easily see the shape of the boat because of the impression it left in the earth.38

In this case, we do know for certain that there once was a body here, because the archaeologists found a few teeth and some fragments from an arm bone. They also found the remains of an iron sword and parts of a shield—which had been placed on top of the body chest. The boat contained the Viking’s spear, a bronze pin, and a bronze piece from what may have been a drinking horn.39

In this chapter, I have elaborated upon my answer to the journalist who asked how we archaeologists can be so certain of our dates. I hope it is now a bit clearer how we date things, but it should also be clear that we aren’t always able to pin something down to a specific year, and why there is frequently some wiggle room, especially in radiocarbon dating, in which dates are always given with a plus-or-minus factor and a statistical probability. New techniques are being invented and applied fairly often, and so I suspect that our ability to date things from the past will continue to get more accurate in the future.

I have also touched briefly upon how some things have been preserved for us to find, especially in the case of organic materials that may require extreme conditions in order to survive. It will almost certainly also be possible to improve our methods in the excavation of organic objects or materials, including those that do not take kindly to being exposed by archaeologists after centuries or millennia of burial.