Shifting silently through the bitter December cold like eerie portents on the battlements of Elsinore, the shadowy figures set off the dogs. They in turn roused the occupant of the house near the intersection of the Pennington road and the highway connecting Trenton to Princeton to the north. Out he came, “violent and determined in his manner, and very profane,” according to a young revolutionary soldier.1 Convinced he was confronting soldiers of the British army before dawn on this day following Christmas, the resident ordered them off.

The young lieutenant, merely eighteen years of age, who earlier that year had been a sophomore at the College of William and Mary, assured the furious local that he and his men were Continentals, an advance detachment of the Third Virginia Regiment under the command of Captain William Washington; whereupon the good, though still sleepy, man insisted that the lieutenant and freezing platoon come inside for food and warmth. Citing their duty to protect the road into Trenton, the soldiers reluctantly declined. Now suddenly alert, the resident identified himself as Dr. John Riker, brought welcome food out to the hungry soldiers, and insisted on joining them. “I may be of some help to some poor fellow,” he said, and immediately enlisted as a surgeon-volunteer in the Continental army of America. It was about seven-thirty in the morning, December 26, 1776.

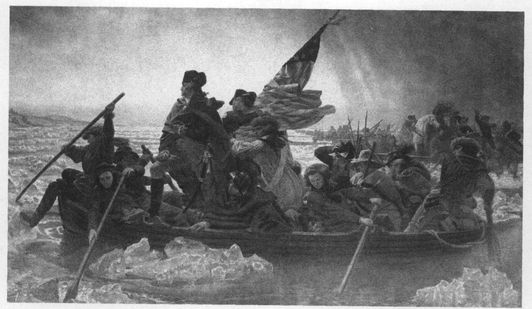

Leutze’s famous painting Washington Crossing the Delaware showsWashington’s lieutenant, the future president James Monroe, holdingthe American flag.

Led by General George Washington who, with an army of about 2,400 men, had just crossed the Delaware River on his flat-bottom Durham boat, the main American columns arrived shortly down the main highways from the north. Within minutes, the Continental army set upon the Hessian forces at Trenton, still abed, and fierce fighting ensued. On King Street in the center of town, the Hessians unlimbered artillery pieces aimed at the American regiments pouring down the streets from the north.

Joined by New Englanders led by Sergeant Joseph White, Captain Washington and the Third Virginians charged the guns. At the head of his troops Captain Washington attacked, ran off the enemy troops around the cannon, and took possession of them, going down with severe wounds to both hands. His lieutenant assumed command of the company and continued the assault. Very soon he took a musket ball high in the shoulder, severing an artery. But Dr. John Riker, the New Jersey physician who had volunteered only an hour or two before, clamped off the artery and saved his life.

There is no evidence to establish that the young lieutenant had occupied General Washington’s barge earlier that morning, but he

would be immortalized some seventy-five years later by the painter Emanuel Leutze as a determined figure placed immediately behind Washington in his painting Washington Crossing the Delaware. That lieutenant, made captain for his bravery at Trenton later in the day, would become the fifth president of the United States and the last veteran of the American Revolution to serve in that capacity. His name was James Monroe.

From the spring of 1776, when he was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Third Virginia Regiment at the age of seventeen, until near the close of 1781, when as a twenty-three-year-old colonel his duties ended, James Monroe was a military man. For virtually the entire first five years of his early adulthood, Monroe saw military service in the cause of the American Revolution.

Like Washington, but unlike John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, or James Madison, Monroe was a military man before he was a diplomat or politician. And like Andrew Jackson and other military veterans to follow, Monroe viewed the future of the young republic through the lens of what today we would call defense or national security. The faint but lingering smell of gunpowder would cause him to be concerned with defining the nation’s southern and western boundaries and its position in the Western Hemisphere.

Monroe lacked Jefferson’s eclectic didacticism and Madison’s conceptual grasp of political theory. But like Washington, he knew how to mount a warrior horse, ford an icy river, and lead men in combat. If the world, or at least the Revolutionary American world, could be divided between men of thought and men of action, Monroe and his commander in chief, George Washington, were very much men of action.

Action for James Monroe began even before his lieutenant’s commission. Even before the battles at Lexington and Concord, William and Mary students were organizing militia companies and conducting drills on the Palace Green in Williamsburg in full view of Lord Dunmore, the Crown’s governor in the Virginia colony. Within days of Lexington and Concord and before fleeing his governor’s mansion,

Dunmore had prudently ordered ashore the crew of His Majesty’s ship Magdalen in the dead of night to empty the local powder magazine, fearing, he told the suddenly alerted townspeople, a slave uprising. This patent subterfuge, when coupled with news of the dead Massachusetts minutemen received on April 29, 1775, caused Dunmore to flee for his life within days. His departure was hastened, no doubt, by the growing number of student militia companies and frontier units, one of which was led by a young John Marshall, arriving in Williamsburg.

No record confirms James Monroe’s participation in these militias, but given his early physical maturity, familiarity with military drill, and participation in a youthful band that liberated the arsenal stashed in the abandoned governor’s mansion, it is difficult to imagine him in absentia from the militarized hothouse of revolutionary Williamsburg. Upon receiving his second lieutenant’s commission, he was not yet eighteen, but, in the words of one biographer, “he was tall and strong, an excellent horseman and a fine shot.”2

The Third Virginians, commanded by Colonel George Weedon of Fredericksburg, joined Washington’s Continental army at Harlem Heights, north of New York City, in mid-September 1776. For Monroe’s immediate commander in the regiment’s seventh company, Captain William Washington, it was a reunion with his more famous distant cousin. The British under Lord Richard Howe, having landed in Manhattan at Kip’s Bay (now the foot of East Thirty-fourth Street), had moved northward, and a skirmish that came to be known as the Battle of Harlem Heights ensued. It was Monroe’s first experience under enemy guns.

By the end of October, Washington, whose forces were outnumbered by at least two to one, with desertions widening the odds constantly, withdrew to New Rochelle, then to White Plains, where, on the twenty-fifth, Monroe participated in a “brief, bloody battle.”3 Washington then divided his forces, and shortly thereafter the Continental detachments sent to defend Fort Washington and Fort Lee were defeated. Uncertain of Lord Howe’s movements, the main body of Washington’s army crossed the Hudson River to

Hackensack, New Jersey, and, closely pursued, thence to Newark. Washington’s retreat continued southward to Brunswick, then to Princeton, then to Trenton, where, in early December, he had all Delaware River boats on that stretch of the river collected across from the city. On the night of December 7, as the Hessian grenadiers under the command of Colonel Johann Rall closed in, the ragged, barefoot Continentals crossed to the Pennsylvania side of the Delaware on the grab-bag riverboat flotilla.

Young Lieutenant Monroe’s regiment was centrally involved in this historic strategic retreat, a retreat described by another of its participants, Thomas Paine, in this fashion:

With a handful of men, we sustained an orderly retreat for nearly a hundred miles, brought off our ammunition, all our fieldpieces, the greatest part of our stores, and had four rivers to pass. None can say that our retreat was precipitate, for we were three weeks in performing it, that the country might have time to come.4

Despite the fact that the Hessians had now dug in at Trenton and waited for warmer weather to cross over and take Philadelphia, Washington recognized what he called “the perplexity of my situation” and that “no man … ever had a greater choice of difficulties, and less means to extricate himself from them.”5

The means by which Washington chose to extricate himself from these difficulties was notable for its audacity and was, to some, the turning point of the Revolutionary War. He would choose Christmas night to recross the ice-choked river and attack the enemy: “Necessity, dire necessity, will, nay must, justify an attempt,” he claimed by way of explanation. As each regiment mustered on that bitter Christmas night, Washington had read to them Thomas Paine’s exhortation written (in words reminiscent of Shakespeare’s Henry V) days before: “These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country. But he that stands it now

deserves the love and thanks of man and woman.” Early the next morning as they poised before the sleeping city of Trenton, the watchword was “Victory or death.”

James Monroe’s regiment was among the first to cross the Delaware on December 26. Captain William Washington’s company was quickly dispatched, between three and four in the sleet-driven morning, southward from the ford at McKinley’s Ferry to seal off the intersection of the Pennington and Lawrenceville roads north of Trenton against any early morning traveler inclined to alert the slumbering Hessians. When artillery pieces were finally offloaded from the Durham boats, two columns, one under General John Sullivan, down the River road, and another under General Nathanael Greene, down the Pennington road (including an artillery battery under Captain Alexander Hamilton), moved on Trenton shortly after dawn.

Sullivan’s cannon were the first to open up. Hessians poured from their barracks and manned two brass three-pound guns pointed up King Street at William Washington’s rapidly advancing company. It was in this action that Washington’s hands were badly injured in the successful and necessary assault on the guns and Lieutenant Monroe took the musket ball to the shoulder that could have ended his life had the severed artery not been tied off by his new patriot friend Dr. Riker. Made captain by George Washington for his bravery, and after two months’ recuperation, the eighteen-year-old Monroe returned to Virginia on a recruitment trip to raise more troops for the Continental army.

By August 1777, with no company of his own to command, Captain Monroe returned to the Continental army and became an aide to Lord Stirling (Major General William Alexander), a colorful soldier with an ancient Scottish title. Monroe saw action at Brandywine Creek on September 11, where he tended to a wounded Marquis de Lafayette—who became a lifelong friend—and participated in a failed surprise attack on British forces at Germantown on October 4. Though Monroe does not appear in dispatches from subsequent battles around Philadelphia for control of the Delaware,

by November 20 he had been promoted to major and made Stirling’s official aide-de-camp.

The historic, miserable, and courageous winter at Valley Forge ensued. The winter and its misery were finally lifted in March 1778 by the announcement of an alliance with France. Then, in mid-June, with the British evacuation of Philadelphia and Washington’s pursuit, once again across the Delaware northward into New Jersey, Major Monroe reported to General Washington that he was within four hundred yards of the British encampment at Monmouth Court House with seventy fatigued men: “If I had six horsemen I think If I co’d serve you in no other way I sho’d in the course of the night procure good intelligence.” Appointed adjutant general to Stirling during the battle at Monmouth, Monroe helped repel the British attack on his division.

Monroe continued to serve under Washington through the summer and fall of 1778, as his army moved back up to White Plains, New York, near where Monroe had first joined up. After spending the winter in Philadelphia and possibly strapped by his self-financed service, Monroe made his way back to Virginia. In the spring of 1779, Monroe received a commission as lieutenant colonel from the Virginia Assembly, but once again the assembly did not have sufficient revenues to raise a militia regiment for him to command. Instead, he was appointed aide to Governor Thomas Jefferson while he began his study of the law. Then in June 1780, he was appointed military commissioner by Governor Jefferson’s council with the mandate to establish a communications link between Baron de Kalb’s southern army, which was facing Cornwallis and Tarleton in North Carolina, and the government of Virginia, thus making Monroe an early military intelligence officer.

By late 1780, Virginia itself had come under attack from advancing British forces and Monroe, now made a colonel, commanded an “emergency regiment,” though it seems to have contributed little to the defense of the Old Dominion. Monroe continued to lobby in various quarters for further militia commands, largely to no avail. With Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown, in November 1781,

Colonel James Monroe, now twenty-three years of age, attended a Peace Ball at Fredericksburg together with senior military officers from the Continental army. Thus officially ended his almost six-year military career.

When Colonel Monroe had departed George Washington’s army in White Plains on May 30, 1779, Washington addressed a letter concerning Monroe to an associate in Virginia. “I take occasion to express to you the high opinion I have of his worth,” he wrote. “He has, in every instance, maintained the reputation of a brave, active, and sensible officer. [I]t were to be wished that the State [Virginia] could do something for him, to enable him to follow the bent of his military inclination, and render service to his country.”6

Admittedly, assessing James Monroe through the prism of his formative military experience and consistent concern for the security of the nation is contrary to convention. For the traditional thumbnail sketch of Monroe comes to something like this: he was the last of the Virginia dynasty, less colorful and probably less intelligent than his predecessors, and he promulgated the Monroe Doctrine (which, the conventional wisdom holds, was really the invention of his secretary of state, John Quincy Adams).

This assessment takes a different course. It seeks, above all, to provide a broader view of the man, especially as patriot and public servant. It explores Monroe’s relationships with three of the dominant figures in his life, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison, all Virginians and all predecessors in the presidency, and suggests that through his diplomatic service to each he was a much stronger and more independent figure than is generally recognized. It also considers the key relationship between Monroe and his secretary of state, John Quincy Adams, especially to determine who actually was the dominant figure. This account positions Monroe as the first “national security” president, whose consistent underlying motivation was to expand and establish the borders of the United States and to make it the dominant power in the Western Hemisphere, free of European interference. In this connection,

there is a detailed discussion of the circumstances leading up to the announcement of the Principles of 1823, later known as the Monroe Doctrine.

By the end of the narrative, it is hoped that readers will have a better understanding of James Monroe—as a more complicated, more nuanced figure than the one traditionally depicted in history books.