Ancient Greece, tetradrachm. These early coins circulated from about 449 to 413 BCE and featured an owl representing the goddess Athena and the power of Athens. (National Currency Collection)

Fraud has been called the second-oldest profession. While the assertion is hard to substantiate, there is little doubt that swindles have been part of life since humankind first engaged in economic transactions. According to ancient Greek mythology, the Titan Prometheus divided a sacrificed animal into two parts: one for the gods and one for humans. In the first pile, he hid the valuable meat under a heap of offal. In the second, he wrapped the bones and skin in rich-looking fat. Asked to choose between the two offerings, Zeus, king of the gods, took the second pile. Having defrauded the gods, Prometheus earned the enmity of Zeus and the gratitude of humanity.

Counterfeiting is a particular type of fraud: an attempt to make a copy of something with the intent to deceive and pass it off as genuine. The counterfeiting of coins began within a few decades of their emergence during the seventh century BCE in Lydia, in what is now Turkey.1 Portable and of a consistent weight and purity, gold and silver coins were an ideal medium of exchange, as well as an efficient store of value—key requirements for an effective currency. However, swindlers quickly took advantage of the ignorant and unwary by manufacturing cheap imitations. After making a mould from a genuine coin, they replaced some or all of the gold or silver with base metals. Sometimes, a base metal core was plated with precious metal to give the appearance of a genuine coin. Such was the ease and financial attraction of counterfeiting that fraudulent coins became a major problem, sometimes reaching “epidemic proportions,” throughout the ancient world.2

Ancient Greece, tetradrachm. These early coins circulated from about 449 to 413 BCE and featured an owl representing the goddess Athena and the power of Athens. (National Currency Collection)

England, Charles I shillings (1625–49). On the left is an original coin, while the coin on the right is a shilling after it has been clipped. (National Currency Collection)

Since coins were made from hammered blanks, it was difficult to ensure a standard coin diameter. Consequently, they were also susceptible to “clipping,” in which metal was trimmed or filed off the edges, leaving the coins underweight. To help deter this practice, the Romans invented the “collar,” which surrounded the die used to manufacture coins. When the heated blank of precious metal was hit with a sledgehammer, the collar stopped the metal from extruding beyond the die.3 While fraudsters could still clip coins made in this fashion, the public could detect the resulting underweight coins more easily. Nonetheless, the clipping of coins remained a significant problem into modern times. Fraudsters also “sweated” coins made of precious metals. Silver or gold coins were put in a bag and vigorously shaken. The resulting dust could later be extracted from the bag.

These two Roman coins illustrate how successive Roman emperors increased the money supply by debasing the coinage. On the left is the 2-denarii piece issued about 216 CE and weighing 5 gm.; on the right is the same coin issued between 260 and 268 CE and weighing 3.5 gm. (National Currency Collection)

Added to the challenges facing money handlers was financial “fraud” perpetrated by the authorities, who were even more capable of debasing the currency and undermining confidence in money than private forgers. In what amounted to legalized counterfeiting, governments surreptitiously reduced the precious-metal content of their coins when times were tough in an effort to stretch their financial resources. In his Natural History, the Roman author Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE) writes: “The Triumvir Antonius [Mark Anthony] alloyed the silver denarius with iron: and in spurious coin there is an alloy of copper employed. Some again curtail the proper weight of our denarii, the legitimate proportions being eighty-four denarii to a pound of silver.”4

Such practices were seldom successful for long. People quickly became adept at assaying the precious metal content of coins by biting them or, more scientifically, by using a touchstone. The money handler would rub a suspect coin on a black stone—usually basalt or jasper—and compare the colour of the rubbing with that of the genuine article.

During the third century CE, as the Roman Empire faced barbarian invasions and civil war, the silver content of the antoninianus (a coin worth two denarii) fell from more than 50 per cent, when it was introduced in 215 CE by the emperor Caracalla, to 2.5 per cent less than fifty years later during the reign of the emperor Gallienus.5 The outcome was rampant inflation.

Medieval kings were equally adept at debasing their currency and defrauding their subjects. To finance his costly wars with Scotland and France, Henry VIII of England debased the English coinage in 1544, contributing to inflation and to the marked decline of the English economy during the last years of his reign. So coppery were Henry’s supposed silver shillings (called testons or testoons) that people wryly joked, “These testons look red: how like you the same? ’Tis a token of grace: they blush for shame!”6

Although little could be done to prevent the sovereign from debasing the coin of the realm, technological advances in the manufacture of coins helped to reduce clipping. During the mid-sixteenth century, “milled” coins were first produced in England. Made using a screw press powered by a horse-driven mill, these coins had a more regular shape than hand-hammered coins, and the “reeded,” or grooved, edge around their perimeter discouraged clipping.7 Many modern coins continue this tradition even though their intrinsic value is usually much less than their face value, and they are consequently unlikely to be clipped. Made from base metals, they are also less likely to be counterfeited than in the past, although bogus large-value coins surface from time to time.

Paper money—invented in China more than one thousand years ago—is more convenient to use and more cost-effective to produce than metallic currency. Introduced to Western countries during the seventeenth century, European paper money initially represented the gold or silver held in vaults by the issuer, typically a goldsmith or, later, a bank. Such “bearer notes” readily changed hands because holders were confident that they could be redeemed in gold “on demand.”8 Today, most money is “fiat” money. In other words, it has no intrinsic value, but is backed solely by a government decree that it is legal tender and, hence, approved for paying debts or settling commercial transactions.9 Like metallic money before it, paper money has been abused by its official issuers. The excessive issuance of paper currency has frequently led to rapid inflation and, in some cases, hyperinflation and economic chaos. Today, in most Western countries, confidence in paper money is sustained through a commitment of the issuing central bank or government to maintain its domestic purchasing power.

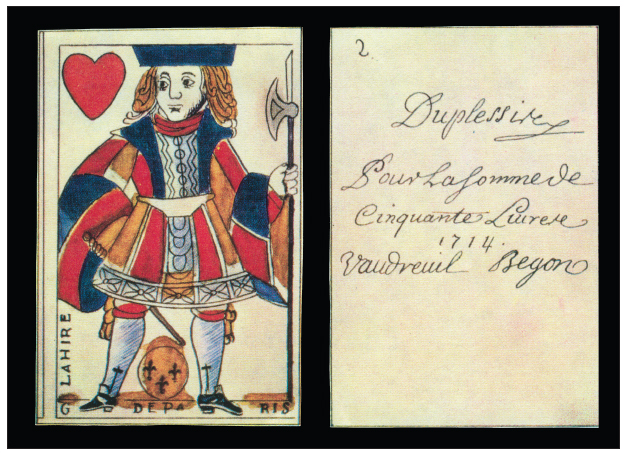

Playing card money, 50 livres, 1714 (reproduction). Canada’s first paper currency circulated from 1685 to 1714. No genuine examples are known to exist.

(National Currency Collection)

The same factors that made paper an efficient and effective form of money also made it attractive to counterfeiters. Early forms of paper money were crudely made, and it was relatively easy for fraudsters to literally “make a quick buck.” Any competent engraver and printer could produce bank notes that would fool the general public. The practice was also very profitable. Forgers could make high-denomination notes as easily and as quickly as small-value notes, and the counterfeiting of paper money quickly became a serious problem everywhere bank notes were widely used.

In North America, the first paper money was issued in New France in 1685 by Intendant de Meulles. Short of coins to pay his troops, de Meulles wrote his name and a value on the back of playing cards and promised to redeem the cards in gold once supplies arrived from France. The cards were well received and circulated freely in the colony. The authorities in Paris, worried about the risk of counterfeiting, were aghast at de Meulles’s actions. In a letter they wrote:

He [King Louis XIV] strongly disapproved of the expedient which he [de Meulles] has employed of circulating card notes, instead of money [gold and silver coins], that being extremely dangerous, nothing being easier to counterfeit than this sort of money.10

The French authorities were right. Bogus card money quickly surfaced, requiring the colonial authorities in Quebec to introduce increasingly severe penalties in a futile effort to stamp out counterfeiting. Nonetheless, card money, as well as other forms of paper money, continued to be readily accepted until the cash-strapped colonial administration began to issue excessive amounts prior to the British Conquest in 1763.

The first paper money in North America’s English colonies was issued by the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1690. As was the case in New France five years earlier, the notes, formally called “bills of exchange,” were issued to pay troops. The other English colonies followed suit during the first part of the eighteenth century. Again, counterfeiters were not far behind. One notorious master counterfeiter was Mary Peck Butterworth (1686–1775), wife of a builder and mother of seven, who lived in Rehobeth, Massachusetts. Around 1715, Butterworth started a family counterfeiting business, employing a number of her relatives. Instead of using engraved metal plates, she apparently transferred the image of a genuine bill using a damp muslin cloth placed over the note and pressed with a hand iron. She then ironed the image onto blank paper, tracing the letters and design by hand.11 It is believed that she counterfeited at least eight different notes issued by neighbouring colonies, which she sold at a 50 per cent discount.

New Jersey, 1 shilling, 1776. Early colonial note, similar to those forged by Butterworth.

(National Currency Collection)

Her operation went undetected until 1723, when the authorities finally grew suspicious. Arrested and her house searched, she was subsequently tried for counterfeiting. Despite testimony from gang members, including members of her own family, Butterworth was found innocent for lack of evidence. She reputedly retired from the counterfeiting business and lived to the ripe old age of eighty-nine. Nevertheless, her activities contributed to a loss of confidence in paper money and may have been a factor behind Rhode Island’s recalling its £5 note in 1727.

Issuers of money have relied on complementary approaches to deter counterfeiting—stiff penalties, including the death penalty, buttressed by robust law enforcement and rigorous note-security measures. During the Song Dynasty (960–1279) in China, private transactions involving mulberry bark were prohibited to forestall counterfeiters obtaining the material used by the government to make paper money.12 In 1666, Sweden’s Stockholms Banco, the first European bank to issue bank notes, began to use watermarked paper in the manufacture of its notes in an effort to foil potential counterfeiters. The Bank of England, which began issuing notes in 1695, followed suit.13 Eschewing portraits or pictures on its notes, which were printed on only one side, the Bank of England relied on the distinctive quality of its white watermarked paper to thwart counterfeiting well into the twentieth century.

Many European countries initially restricted the issuance of paper money to high-denomination notes to ensure that gold and silver coins remained in circulation and out of a concern that small-value notes were most likely to be forged and passed among the uneducated.14 It wasn’t until 1793, owing to a shortage of gold caused by Britain’s conflict with revolutionary France, that the Bank of England began to issue notes smaller than £10, a very considerable sum at that time. Until 1847, the smallest note issued by the Banque du France was FF500, while the smallest German denomination until 1876 was 100 Reichmarks.15 These amounts were far larger than what was needed in most routine day-to-day transactions.

Note issuers in Canada and the United States came to rely primarily on complicated, hard-to-duplicate note designs to prevent counterfeiting. Portraits were particularly popular, since a faithful reproduction of face and hair was extremely difficult for counterfeiters to achieve. Later, complicated geometric designs were routinely added to notes as a further security device. Intaglio printing, which produced raised lines of ink that could be sensed at the touch of a finger, was also extensively used. Intaglio printing presses, which were expensive to build and required highly skilled operators, were thought to be beyond the reach of most potential counterfeiters. As another precaution, notes were also hand signed by senior bank officials.

Despite such measures, pressure from counterfeiters forced issuers to constantly upgrade the security devices on their notes. In 1825, Michael Wallace, the provincial treasurer for Nova Scotia, wrote that although the province had up to then “escaped much loss due to counterfeiting,” it was now necessary to procure “some kind of stamp” to put on provincial notes to help deter imitation. He also inquired whether bankers in England had “discovered any improvements in the manufacture of paper for notes that is not liable to be imitated.”16

Technological change left its mark on both the bank-note industry and counterfeiting, with new discoveries favouring either the issuer or the forger for a time. In the early nineteenth century, the shift from copper to more durable steel plates permitted the production of more uniform notes, which facilitated the detection of forgeries. A few decades later, however, the invention of photography gave the upper hand to counterfeiters, until issuers regained the advantage with the introduction of multicoloured notes.

Nova Scotia treasury note, 1821. The crudity of the elements of this early note makes Wallace’s concerns about counterfeiting easy to understand.

(National Currency Collection)

The arms race between the issuers of money and counterfeiters continues. Issuers regularly release new series of bank notes with ever more sophisticated security devices either in response to an existing counterfeiting problem, or pre-emptively to head off a potential counterfeiting threat. The introduction of widely accessible, cheap colour photocopying machines in the 1980s prompted note issuers to take defensive measures, including the addition of microprinting, metallic threads, and optical security devices that shift colour as light hits the note. Recently, the threat has come from high-quality digital imaging and printing. Issuers have responded with holographic stripes, fluorescent inks, and other advanced techniques to protect their notes. Working with central banks, the makers of photocopiers and scanners have installed note detectors in their equipment to forestall their use in counterfeiting. Some countries have also replaced paper with a plastic substrate. Very durable, the new plastic substrate is more difficult to counterfeit. In 2011, Canada introduced a new series of bank notes using a plastic substrate, beginning with the $100 note. The other denominations will be issued by the end of 2013.

Through the ages, counterfeiting has attracted small-time crooks, as well as organized professional gangs. For the most part, the former have had limited impact on the economy, given the small scale of their activities. Today, such counterfeiters typically turn out low-quality, easily detected copies using desktop scanning equipment and inkjet printers. Of far greater concern are gangs that fabricate and distribute counterfeit notes on a large scale, using state-of-the-art computer imaging and other equipment. These criminal gangs are often involved in other serious illegal activities. Given the scope of such operations and the quality of the bogus notes produced, the impact on public confidence in currency can be large and lasting. State-sponsored counterfeiters also pose a particular concern and challenge for countries such as the United States, whose currencies are widely used internationally. Such counterfeiters have at their disposal the same specialist tools used by legitimate bank-note issuers. Their product is therefore of the highest quality and can fool even experienced note handlers.

It is now generally agreed that the best defence against counterfeiting is a knowledgeable public, and central banks and law enforcement agencies devote considerable resources to educating note handlers in the banking and retail sectors, as well as the general public, about the features of genuine notes and how to detect forgeries. Staying alert and being aware of the security features of your bank notes will go a long way in ensuring that you don’t become a counterfeiting victim. Counterfeiters do not respect national frontiers, and national law enforcement agencies actively co-operate at the international level. Bank-note printers and central banks also work closely together to suppress counterfeiting.

You might think that with the declining use of paper money and coins in favour of debit and credit cards, and even electronic cash, counterfeiting would be decreasing in importance. This is far from the truth; counterfeiting remains a major public policy issue. In Canada, more than $61 billion in bank notes were in circulation in 2012, equivalent to roughly $1,800 per person. A 2004 survey also revealed that 13 per cent of Canadians have been offered or received a counterfeit note, at one time or other.17 Consequently, we all have a stake in ensuring that counterfeiting of our currency is limited to the extent possible.

Weapons seized in “Project Ophir,” which shut down Canada’s largest counterfeiting operation (see chapter 10). These are dangerous people!

(Courtesy RCMP)

Improved note security, combined with rigorous law enforcement and extensive public education on how to identify false bills, has reduced direct losses from passed counterfeit Canadian notes to $1.6 million in 2012, down from $13 million in 2004.18 However, the total cost to society of counterfeiting paper currency is far higher, given the expenses associated with the development and the manufacture of high-security bank notes, as well as the cost of law enforcement.

Moreover, the debit and credit cards that have generally replaced cash in large-value transactions are also subject to illegal duplication. In 2011, losses in Canada from counterfeit debit and credit cards alone totalled more than $190 million—many times the losses associated with counterfeit bank notes.19 These losses and the expense of security measures taken to protect users from fraud are passed on to the consumers of financial services in the form of higher service charges. The growing use of Internet banking and electronic money also present new opportunities for high-tech fraudsters and new challenges for law enforcement agencies and the financial institutions and other corporations that provide payment services.

THE STRANGE STORY OF THE MARIA THERESA THALER

The ubiquitous Maria Theresa thaler.

(National Currency Collection)

When is a copy of a coin not a counterfeit—when it’s a Maria Theresa thaler. This silver coin, dated 1780 and bearing the likeness of the Hapsburg Empress Maria Theresa (1717–80) of Austria and Hungary, has been produced in many countries, including Austria, Britain, Belgium, the Netherlands, Italy, and India.20 It is still produced by the Austrian mint even though it ceased to be legal tender in Austria in 1858.21 Popularized by European merchants, the Maria Theresa thaler became widely used as a trade currency throughout the Middle East and the Horn of Africa during the late eighteenth century, giving rise to the improbable situation of a buxom, elderly woman gracing the coinage of Muslim Africa and Arabia. Known by many names, including the Levantine thaler, the riyal nimsawi in Arabic, or la grosse madame in French,22 the coin was legal tender in Saudi Arabia until 1928, in Ethiopia until 1945, in Yemen until 1962, and in Muscat and Oman until 1970.23 In a region often beset by political and economic turmoil, the thaler’s sustained popularity as a medium of exchange and a store of value lay in its unvarying nature, particularly its silver content, something to which all thaler manufacturers assiduously adhered.

Before Britain’s Royal Mint began producing the coins in the mid-1930s, it sought a legal opinion as to whether doing so would constitute counterfeiting. The opinion argued that “because the coins bore the portrait of a 200-year-old monarch of a state that no longer existed and were of a denomination long superseded, the Maria Theresa thalers were simple metallic disks with a design, despite the custom of referring to them as money.”24

Coin or disc, counterfeit or genuine, the Maria Theresa thaler has become the stuff of legend. Thalers helped finance a pilgrimage to Mecca by the famous nineteenth-century explorer Sir Richard Burton disguised as a Pashtun tribesman.25 They were also used by the Anglo-Egyptian Expeditionary Force in its failed attempt to relieve Khartoum and General “Chinese” Gordon besieged by the Madhi in 1885.26 Most recently, it was reported that Yemeni workers expelled from Saudi Arabia during the first Gulf War in 1991 took home much of their savings in the form of—you guessed it—Maria Theresa thalers.27

NUMISMATIC FORGERIES

When we think of counterfeiting, we typically think of forgers defrauding the public by copying notes or coins that are currently circulating and passing them off as genuine. But there is also a thriving trade in numismatic forgeries: copies of currency that is no longer in circulation. Numismatic forgers prey on the unwary collector, reproducing old money that is in high demand, such as ancient or medieval coins.

Such fraud has a long pedigree. Carl Wilhelm Becker (1772–1830), who learned his trade at the Royal Bavarian Mint in Munich at the end of the eighteenth century, made copies of at least 360 different Greek, Roman, and medieval coins. While he apparently counterfeited for fun rather than profit, many coin collectors, including royalty, were defrauded. In 1911, the Kaiser Friedrich Museum in Berlin, which had obtained the dies that Becker used to make his coins, sent warnings to prominent numismatists to closely examine their collections and remove Becker imitations. So good are Becker’s fakes that they have themselves become collectible!28

Replicas of old coins frequently turn up at coin shows and in online auctions. To help reduce the risk of fraud, the U.S. government passed the Hobby Protection Act in 1973, forbidding the importation of replica coins that did not prominently carry the word “COPY.”29 There is no similar law in Canada, although anyone attempting to knowingly pass a replica as the genuine article would be guilty of fraud. In 2009, a number of good Chinese-made imitations of rare old Canadian coins appeared for sale on eBay. Following consultations with the RCMP, who considered them counterfeits, eBay removed all current listings of the coins from their North American sites. Nevertheless, a number of the bogus coins are believed to have been purchased by collectors.30

ENDNOTES FOR CHAPTER ONE

1K. Peters, The Counterfeit Coin Story: Two and a Half Thousand Years of Deception (Biggin Hill, Kent: Envoy Publicity, 2002), 1.

2Ibid.

3RCMP, Law and Order in Canadian Democracy: Crime and Police Work in Canada, rev. ed. (Ottawa: Edmond Cloutier, 1952), 203.

4Pliny the Elder, The Natural History [Naturalis Historia], trans. J. Bostock and H. T. Riley (London: Henry G. Bohn, 1857), Book XXXIII, Chapter 46, 128.

5Bank of Canada, Beads to Bytes: Canada’s National Currency Collection (Ottawa: Bank of Canada, 2008), 56.

6Peters, The Counterfeit Coin Story, 70.

7See Early Milled Coins at http://www.kenelks.co.uk/coins/earlymilled/earlymilled.htm.

8Current British bank notes continue to bear the words “I promise to pay the bearer on demand,” even though they are no longer backed by gold. Should someone try to redeem a note at the Bank of England, the individual would receive only a new crisp one in exchange, rather than gold. A similar phrase was dropped from Canadian bank notes, beginning in 1969 with the release of the Scenes of Canada series. It was replaced with “This note is legal tender.”

9Bank of Canada, Annual Report 2003 (Ottawa: Bank of Canada, 2004), 30.

10Letter to de Meulles, 20 May 1686, in A. Shortt, Documents Relating to Canadian Currency, Exchange and Finance during the French Period, vol. 1 (Ottawa: F. A. Acland, 1925a), 79.

11E. C. Rochette, Making Money: Rogues and Rascals Who Made Their Own (Frederick, CO: Renaissance House Publishers, 1986), 10. See also J. Rada, “Mary Peck Butterworth: A Master Counterfeiter in Colonial America,” 2008. http://suite101.com/article/mary-peck-butterworth-a67314.

12A. Heinonen, “Counterfeit Deterrence: Beating the Criminal Element,” Counting Currency, 2010, http://countingoncurrency.com/news-item/counterfeit-deterrence-beating-the-criminal-element.

13Ibid.

14V. Smith, The Rationale of Central Banking and the Free Banking Alternative (first published 1936, republished Library of Economics and Liberty, 1990), vii.8, http://www.econlib.org/library/LFBooks/SmithV/smvRCB1.html.

15K. W. Bender, Moneymakers: The Secret World of Banknote Printing (Weinheim: Wiley–VCH Verlag GmbH & Co., 2006), 22–24.

16V. Ross, The History of the Canadian Bank of Commerce, vol. 1 (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1920), 37.

17V. Taylor, “Trends in Retail Payments and Insights from Public Survey Results,” Bank of Canada Review (Spring 2006): 33.

18Bank of Canada, Bank of Canada Banking and Financial Statistics, Table B4: “Statistics Pertaining to Counterfeit Bank of Canada Notes,” February 2013.

19Canadian Bankers Association, “Credit Card Fraud Statistics—American Express Canada, Mastercard Canada and Visa Canada, year ending December 2011,” http://www.cba.ca/contents/files/statistics/stat_creditcardfraud_en.pdf. Credit and debt card fraud was much higher, totalling more than $500 million.

20A. E. Tschoegl, “Maria Theresa’s Thaler: A Case of International Money,” Eastern Economic Journal 27, no. 4 (2001): 443.

21Austrian Mint at http://www.austrian-mint.at/mariatheresienthaler?l=en.

22P. Harrigan, “Tales of a Thaler,” Saudi Aramco World 54, no. 1 (2003): 14–23, http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/200301/tales.of.a.thaler.htm.

23Tschoegl, “Maria Theresa’s Thaler,” 444.

24Ibid., 450.

25C. Semple, A Silver Legend: The Story of the Maria Theresa Thaler (London: Barzan Publishing, 2005), 59.

26Tschoegl, “Maria Theresa’s Thaler,” 447.

27Semple, A Silver Legend, 96.

28Rochette, Making Money, 2. See also Offenbach city portal, 28 February 2006, http://www.offenbach.de/offenbach/themen/unterwegs-in-offenbach/kultur/haus-der-stadtgeschichte-museum-und-archiv/schausammlung/neuzeit/article/Muenzen_-_Becker.html.

29R. Goldsborough, Ancient Coin Replicas, 2010, http://counterfeitcoins.reidgold.com/replicas.html.

30RCMP, Counterfeit Canadian Coins, 2011, http://www.bc.rcmp.ca/ViewPage.action?siteNodeId=912&languageId=1&contentId=-1.