United States, Columbia Bank, $1, 1852. A typical note from the free banking period in the United States.

(National Currency Collection)

During much of the nineteenth century, counterfeiting was rampant throughout North America, especially in the United States. Its prevalence reflected both social and economic factors, including the development of a more anonymous and complex society, the nature of the financial system, as well as weak legal and regulatory systems, especially in lawless frontier regions.

As long as the population remained largely rural, and communities were small, the scope for counterfeiting was limited. Shopkeepers and merchants knew their customers and their reputations, and accepted payment largely in coin. But as immigration intensified, towns and cities expanded rapidly. Roads, canals, and railway networks connected previously isolated communities, making it increasingly difficult for merchants and shopkeepers to know with whom they were dealing. Shortages of gold and silver coins also encouraged the introduction and acceptance of paper money, first issued by colonial authorities and later by private banks. Although paper notes were a more efficient form of money than coins, the potential for counterfeiting was much greater.

The establishment of private banks, which underwrote the burgeoning North American economy, also ironically provided new opportunities for counterfeiters. In the nineteenth century, a key function of banks was the circulation of bank notes.1 Banks did this by issuing their own notes to borrowers as well as to depositors withdrawing money from their accounts. These notes then passed from hand to hand, with people’s willingness to accept them contingent on their confidence in the issuing bank and its readiness to redeem the notes into gold “on demand.” Confidence in bank notes was sustained by the reputation of the bank and by banking laws that obliged banks to maintain adequate reserves of gold in the event that their notes were presented for redemption. Failure of a bank to convert its notes into gold on demand would typically result in its closure.

The first banks in North America were chartered in the United States at the end of the American Revolutionary War. The Bank of Pennsylvania was started by a group of Philadelphia merchants in 1780, followed by the Bank of North America in 1781 and the first Bank of the United States ten years later. Others quickly followed, virtually all of which were state-licensed institutions. Banking was viewed by the general population as a kind of financial alchemy—a “form of secular witchcraft”—that led to increased prosperity by converting bits of paper into tangible assets.2 More banks meant the issue of more paper money to fund both sound and speculative activities. Lax banking laws had the support of potential borrowers and politicians, as well as entrepreneurs, both honest and unscrupulous. During what is known as the “free banking” period (1837–62), there was an explosion of new banks in the United States, as states issued licences to anyone who could satisfy (low) minimum standards regarding capital and other requirements. These banks operated on a unit basis: branch networks were not permitted. Many banks failed but were quickly replaced by others. By 1840, more than 700 banks were operating in the United States, and by the early 1860s, the number had almost doubled.3

During the late eighteenth century, counterfeiters shifted their attention from the paper money issued by colonial authorities to notes issued by banks, which were gaining widespread popularity. By 1794, counterfeit bank notes were already posing a serious problem. That year, the Bank of North America and the Bank of the United States posted bills in taverns and other public places jointly offering a reward of up to $1,000 for the capture of counterfeiters.4

United States, Columbia Bank, $1, 1852. A typical note from the free banking period in the United States.

(National Currency Collection)

The growing number of banks, each issuing its own money, meant that the general public used a bewildering mixture of notes, issued in various designs, sizes, and denominations. There was no standardization.5 By one estimate, “more than 10,000 different kinds of paper” were circulating in the United States by the early 1860s.6 It became virtually impossible for the public to distinguish good notes from bad—a fertile environment for counterfeiting and the passing of other types of bogus money. An 1862 article in the New York Times stated that few banks had “escaped the attempts at imitation.”7 Commenting further, it noted:

There are very few persons, if any, in the United States, who can truthfully declare their ability to detect at a glance any fraudulent paper money. So numerous are our Banks, and so varied the tricks of the counterfeiter, that even professional detectors of bad bills, brokers, bank tellers and others in the constant habit of handling large sums of money, are frequently imposed upon.

Imitations of genuine bank notes were just one element—and not necessarily the most important—of a far broader problem of financial fraud involving bank notes in North America. Other types of worthless paper also circulated, including raised, or otherwise altered, notes and notes issued by spurious banks. Valueless notes of genuine but failed banks were also passed by the unscrupulous to the uninformed. In such a chaotic financial world, a well-made counterfeit of a note issued by a sound bank might be preferred to the legitimate note of a bad bank. What mattered was the holder’s degree of confidence that he could pass the note on to someone else.

Raised notes were genuine bank notes whose denominations had been “raised” from a low to a higher denomination. Counterfeiters would use a solvent to erase the original indications of value and then replace them. Counterfeiters would also obtain notes issued by defunct banks and alter them to resemble the notes of sound banks. In this case, forgers took advantage of the fact that many banks had similar names. In 1862, the New York Times commented that there were twenty-four “Union Banks” and twenty-three “City Banks” in operation.

Counterfeiters could legally acquire the plates and dies of genuine bank notes at “sheriff sales,” when the effects of failed banks or engraving firms were liquidated. The dies would be combined in different ways to simulate genuine bills, allowing bogus notes to be engraved to the highest standard of the day.8 In an 1852 letter to the editor of the New York Times, a bank-note expert recounted that of twenty-one counterfeit plates shown to him by the mayor of Philadelphia, “the largest number were the genuine productions of our largest bank-note engraving establishments” rather than of the counterfeiters themselves.9

$1 raised to $4, 1878. Here, the value of an authentic $1 note (shown above) has been “raised” to $4 in the note below.

(National Currency Collection)

Spurious banks, sometimes called “phantom” or “wildcat” banks, were also established with little or no capital for the sole purpose of defrauding the public by circulating near-worthless notes. Although offices were ostensibly established to permit the conversion of notes into gold on demand, they were located far from where the notes were circulated to discourage redemption. If large amounts were nonetheless presented for conversion into gold, the banks would close. During the late 1830s, a dozen or so spurious banks, reportedly operated by U.S. fraudsters, maintained “very modest and obscure offices” in Lower and Upper Canada. Their notes, engraved to resemble those of honest banks, were “pushed” in the United States.10

Such was the scale of financial fraud involving bank notes in the United States that as much as one-third to one-half of U.S. bank notes in circulation at the end of the U.S. Civil War (1861–65) were counterfeit.11 The proportion of bad notes was often higher in frontier areas than in cities, owing to weaker law enforcement.12 One observer wrote: “It may be safely stated that the art [counterfeiting], as pursued in the United States, is without parallel, and that without vaunt or hyperbole, we can ‘beat the world’ on this, our national speciality—counterfeiting.”13

Confederate States, $20, 1861. Issued just before the outbreak of the Civil War, Confederate notes were not backed by any assets. Instead, they carried the phrase “Six months after the ratification of a treaty of peace between the Confederate States and the United States the Confederate States of America will pay” [the amount of the bill] “to bearer.”

(National Currency Collection)

According to the 1862 New York Times report, altered notes accounted for more than 50 per cent of the almost 6,000 different types of bogus bills circulating in the United States. Notes issued by spurious banks represented roughly 30 per cent. Actual “bona fide” counterfeits of genuine bank notes accounted for less than 10 per cent of the total, with other forms of bad notes, including photographs of real notes and notes of failed banks, making up the difference.14 The report commented that the true counterfeits of real notes were typically poorly done, because of the skill and equipment required to duplicate genuine bank notes. It argued strenuously for currency reform, as well as tougher laws that would, among other things, make it illegal to purchase the engraved bank-note plates of failed institutions, to imitate the notes of another bank, and to establish banks of the same name. It also called for stricter enforcement of existing anti-counterfeiting laws.

Amazingly, the situation was worse in the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War. The breakaway states were flooded with counterfeit notes, many of which originated in the north, possibly with the tacit support of the Union Government.15 A Philadelphia printer, Samuel C. Upham, made excellent “souvenir” copies of Confederate bank notes on high-quality paper that were subsequently widely circulated. A Confederate congressman is reported to have said that Upham did more damage “than a whole Union army.”16 So widespread were the counterfeits and so perilous the state of affairs, that the Confederate government was obliged to legalize the use of counterfeit “greybacks.”17 This led to extraordinary price inflation.

Army Bill, $25, 1813. Printed in Quebec City and used to pay troops during the War of 1812, these notes restored confidence in paper currency when redeemed in full after the war.

(National Currency Collection)

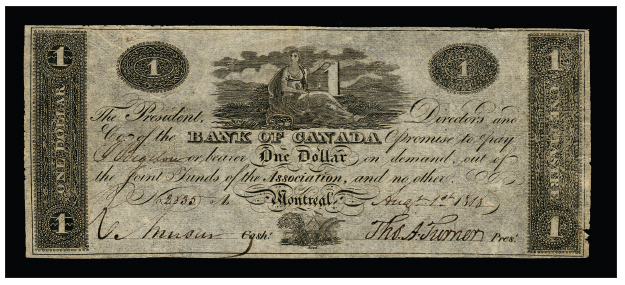

Counterfeit Bank of Canada, $1, 1818. A very early Canadian counterfeit note.

(National Currency Collection)

As was the case in the United States, banking began to flourish in Canada during the early nineteenth century. Previously, Canadians had been unwilling to put any faith in paper money, given their negative experience with card money issued by the earlier French regime. Those bills had become worthless as a result of massive over-issuance prior to the British Conquest. However, a more positive experience with “army bills,” issued by the Lower Canada government during the War of 1812, and subsequently repaid in full, re-established public confidence in paper money.18 With the ground so prepared, the general public was ready to accept notes issued by newly established Canadian banks. The Bank of Montreal, founded in 1817, was the first successful Canadian bank.19 Modelled on the first Bank of the United States, it received its government charter in 1822.20 Other banks quickly followed, including the Quebec Bank (Quebec City) and the Bank of Canada (Montreal) in 1818, the first Bank of Upper Canada (Kingston) in 1819, the Bank of New Brunswick (St. John) in 1820, the second Bank of Upper Canada (York) in 1821, and the Bank of Nova Scotia (Halifax) in 1832.21

Canadian banks differed significantly from those in the United States, however. They typically operated on the basis of a government charter that was comparatively difficult to obtain. They were also well capitalized and operated branch networks that spread their risks. Consequently, there were proportionately far fewer banks in Canada than in the United States and hardly any failures. Although an Act of Parliament in 1850 permitted free banking along U.S. lines, only a handful of such banks were established, owing to the extensive branch networks of the existing chartered banks that already served the public well, a lack of investor interest, and concerns about small banks issuing bank notes.22 The failures of small banks in the United States likely provided a cautionary example.

Note detectors, such as this one published in New York in 1934, supposedly helped merchants to spot “bad” notes.

(National Currency Collection)

As a result, only ten banks were in operation prior to the union of Upper and Lower Canada in 1841. This number rose to twenty-two by Confederation in 1867 and peaked at forty-one in 1885.23 The relatively small number of banks meant that Canadians were more familiar with the bank notes in circulation than residents south of the border, and were better able to spot bogus bills. Nonetheless, counterfeiting was an ongoing concern, heightened by the fact that U.S. bills, with which Canadians were less familiar, circulated freely across the border.

The prevalence of so many different types of bogus bank notes in North America led to a thriving industry in bank-note authentication. So-called note “detectors” were published regularly and sold to merchants in Canada and the United States. They provided detailed descriptions of the various forms of bad money in circulation, both U.S. and Canadian, including counterfeits of genuine notes, raised or otherwise altered notes, notes of spurious banks, as well as notes of “broken” or failed banks. Bank-note “experts,” preying on the public’s understandable fears, went from city to city peddling such books. Although consulted routinely by retailers and their customers, these detectors were of little use. They were seldom up to date and probably helped counterfeiters as much as law-abiding citizens.24

Home Bank of Canada, $10, 1917. Following the failure of the Home Bank of Canada in 1923, a Chicago police publication claimed that Home Bank notes were spurious and worthless and indicated that it was taking vigorous steps to combat them. In reality, the notes were worth more than their face value. Under the Bank Act, notes of failed chartered banks immediately began to earn 5 per cent interest until the date set by the Minister of Finance for their redemption. Upon redemption, holders of Home Bank notes received the face value of returned notes, plus accrued interest, from the bank’s liquidators. Canadian bank notes were secured by a first charge against the failed bank’s assets, buttressed by a circulation-redemption fund into which all banks contributed.

(National Currency Collection)

THE EXTRAORDINARY MRS. W. DAVIDSON

At the beginning of September 1859, a woman calling herself Mrs. Davidson arrived in Toronto, staying at Revere House, located on the current site of the Royal York Hotel. She appeared to be “flush with money,” dressed in a “handsome black silk dress, crepe bonnet, silk cloak, and black veil,” and wearing a considerable amount of valuable jewellery, including diamond rings and brooches. Supposedly from New York, she was “about thirty-four years of age, with sharp plain features.”25 She quickly became well known in the city, visiting both retail and wholesale stores and asking to inspect dry goods: typically fine silks, satins, and ribbons. She seldom purchased anything of value, however, claiming that the goods were either of inferior quality or too expensive.

Merchants became suspicious when items began to disappear about the time of her visits. Detectives were called in, and a warrant for her arrest was issued after a case of ties stolen from the wholesaler W. McMaster and Nephews of Yonge St. was found close to where she had been seen standing in a neighbouring store. Arrested at Revere House, Mrs. Davidson was taken into custody. Brought to City Hall and questioned by the Mayor, she was released on lack of evidence but not before a police search uncovered suspicious U.S. bank notes—a $1,000 bill on the Bank of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; a $100 bill and a $50 bill, both on the Exchange Bank of Pittsburgh; and a $10 note on the Bank of Weston, Virginia. The bills seemed well worn, although the police could not tell whether this was legitimate wear and tear or was the result of artificial “rumpling” or “sanding.” The detectives confiscated the bills to have them assessed by currency brokers.

The next day, Mrs. Davidson was again picked up by police following a complaint that she had tried to steal a piece of silk from Mr. W. B. Lyle’s store on Front Street. In the meantime, with three different brokers saying that all the notes except the $10 bill were forgeries, Mrs. Davidson was charged with possession of counterfeit notes—a serious crime. Despite her tears and denials, she was held in custody for trial the following day. Claiming that she had committed no offence, she refused to provide her first name, giving only the initial “W.”26

Her case was closely followed by the general public, and the court was crowded with spectators, “all anxious to get a peep of the lady who in a couple of days had attained so much notoriety.” They were disappointed when she remained heavily veiled. Nevertheless, she was reported to seem “a good deal dejected, and wearied, as if ‘nature’s sweet restorer’ had not visited her eyelids the previous night.” Claiming to be unwell, Mrs. Davidson demanded and received a chair. Two currency experts from the Colonial Bank and the International Bank, together with a King Street currency broker each testified that the suspicious bills found in her possession were forgeries.27 Asserting her rights in “true Yankee style,” Mrs. Davidson declared that the experts knew nothing about American money and demanded the opinion of other currency brokers. The magistrate agreed to her request and the prisoner was remanded to the following day.

The trial recommenced with the expert testimony of two new brokers. Mr. W. B. Phipps testified that he had never seen a $1,000 bill on the Bank of Pittsburgh and would hesitate to accept it owing to its “general appearance.”28 The signature of the bank’s president on the note was also suspicious, as it differed slightly from a facsimile of the true signature found in his “Thompson autographical counterfeit detector.” But while he didn’t think it was genuine, he could not say with certainty that it was counterfeit. On the other hand, he thought that the $100 and $50 bills on the Exchange Bank of Pittsburgh were genuine, mainly because the notes were not listed in the detector. However, “as there are many counterfeits afloat on American banks,” and since his note detector was seven years out of date, he couldn’t be sure. “I am no means a good judge of American money,” he told the judge.

Mr. Harrison R. Forbes, another Toronto currency broker, considered all three suspect notes to be photographic forgeries. But Mr. John Ellis, a professional engraver, contradicted this testimony, saying that in his opinion the notes were made from “genuine plates.” He maintained that the printing on the $1,000 bill was too sharp and its colour too black to be a photograph, while the $100 and $50 bills could not be photographic copies because of the red tint on the notes. He could not, however, attest to the authenticity of the signatures on the notes.

The investigation was then postponed in order to find some American gentlemen more familiar with U.S. money. The names of U.S. merchants, brokers, and steamboat agents were given to the presiding magistrate who issued them with subpoenas. Mrs. Davidson was held in jail over the weekend, a treatment that she vehemently protested, complaining of poor conditions and inadequate food. Appealing to the court, she said, “If you gentlemen were in the United States, you would not want to see a lady used in this manner. There they would subscribe to her bail, and they would do all they could to get her sent to a hotel until this investigation is finished.”29 Despite her plea, no one stepped forward to provide the $1,000 bail, and the magistrate returned her to jail. He promised, however, that he would “instruct the Governor of the gaol to make you as comfortable as his arrangement would permit.” He also advanced her $4 to buy better food, saying that she could repay him using the genuine $10 bill on the Bank of Weston, Virginia.

When the trial resumed, it became apparent that the case against Mrs. Davidson was too weak to stand. The Globe newspaper reported that the zeal of the police had outrun their discretion. “That there was something wrong about her there can be no doubt, but she had committed no wrong in Canada which could be proved against her . . . . The attempt to prove the bills [to be counterfeits] had turned out a failure.”30

Commercial Bank of the Midland District, $10, 1854.

(National Currency Collection)

With note detectors being of limited value, store owners also relied on the demeanour and social class of the person proffering a note. Notes from a well-dressed, middle-class woman or man were more likely to be accepted than those offered by someone who looked disreputable. Old notes were preferred over crisp, new-looking notes, on the grounds that worn notes must have been used by others and, thus, had satisfied their scrutiny. Counterfeiters naturally took advantage of these prejudices. They artificially aged bogus notes with tobacco juice and added pinholes to suggest prior handling by banks.31 Counterfeit notes were put into circulation by seemingly “respectable” people. In early 1858, The Globe newspaper warned that excellent lithograph counterfeit $10 notes on the Commercial Bank of the Midland District were being passed in Toronto “by a man of respectable appearance, who generally makes a small purchase, and then pretends he has no bills in his possession of a lesser amount.”32

Not surprisingly, counterfeiting prompted advances in security printing. In 1803, American inventor Jacob Perkins developed the steel plate siderography process for producing bank notes. Up until then, copper plates had been used in printing presses to produce bank notes. But copper plates began to wear after several hundred impressions, causing variations in the notes they produced. Steel plates were far more durable and produced more uniform notes. Perkins deemed the notes produced using his new system difficult, if not impossible, to duplicate. He is quoted as saying, “We believe that an exact uniformity of bills (excepting the name of the bank and town) is the only means by which individuals can be enabled to distinguish between spurious and genuine bills.”33

The new process was very complex. The plate itself was “made up of 57 case-hardened steel dies an inch thick and keyed together in a strong iron frame.” Such a plate took 800 days to produce. Therefore, the time, equipment, expertise, and money needed to duplicate the process were also seen as a huge deterrent to counterfeiters. While steel plates lasted longer than copper plates, they were still subject to wear. Perkins subsequently patented the roller transfer method in which an engraved steel plate became a master die and its image transferred in relief to a soft steel roller. The virtue of this improved method was that new steel plates could be made from the original master die.34

One critic, writing under the pseudonym Philotechnus, was skeptical about the ability of steel technology to eliminate counterfeiting. “I have not the same degree of faith in its infallibility that Mr. Perkins seems to have.” While Philotechnus thought the invention ingenious, he did not believe that note uniformity was achievable. Nor did he feel that, if achieved, it or the expense of the system would be a deterrent. Although bills printed using the system had not been counterfeited up to that point (1806), he argued that it was premature to declare victory against the counterfeiters. He also contended that it was only necessary for bogus notes to be good enough to fool the general public, not an expert printer. For his part, Philotechnus was “fully satisfied that the most perfect security against counterfeit bills, is for the banks, by employing the ablest artists, to have their plates executed in the highest style of excellence.”35

By the 1830s, most banks in North America had adopted Perkins’s siderography process. But Philotechnus proved to be correct: counterfeiting continued to flourish. Philotechnus’s faith in fine artistry was also misplaced, however. Although banks took great pains with the pictures (“vignettes”), portraits and scrollwork that decorated their notes, using the hard-to-master technique of line engraving, counterfeiting remained endemic in the United States and, to a lesser degree, in Canada. In what amounted to an arms race to stay ahead of counterfeiters, bank-note printers made successive improvements in note design and production. These included the “Ormsby” unit system, changes to paper quality, the use of multiple colours to thwart photographic copies, and the introduction of the geometric lathe.

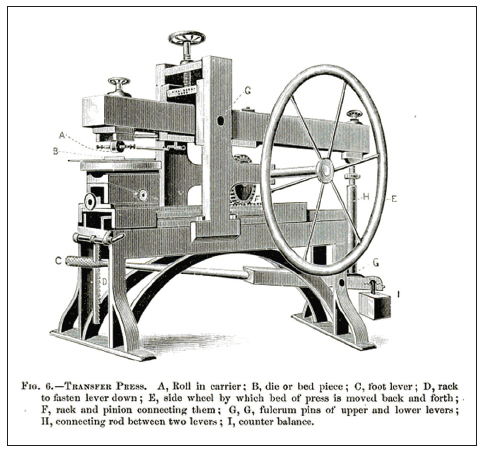

Transfer press. Once a soft steel die was engraved by hand, it was hardened in a bath of potassium cyanide. It could then be duplicated by means of a transfer press. Using the large wheel on the side of the press, the operator rolled a cylinder of soft steel back and forth over the die under intense pressure. The steel was forced into every groove on the die, making a perfect negative replica on the roller, which was then hardened. The hardened roller was then placed back into the transfer press and rolled over another soft steel plate, transferring the original design to the steel plate. Once hardened, this plate was used to make notes.

(Popular Science Monthly, March 1895)

In the Ormsby unit system, developed mid-century by W. L. Ormsby, another American inventor, the bank-note plate was crafted in one piece, rather than comprising many interchangeable dies. In a letter to newly elected U.S. President Franklin Pierce in 1853, which accompanied a copy of his 1852 book Ormsby’s Bank-Note Engraving, Ormsby writes,

Many of the counterfeit bills in circulation are absolutely the work of the original engravers. Counterfeiters obtained their work in spite of the utmost efforts to prevent it. This is owing to the patch work system of constructing the note and the use of dies in the engraving of plates. My plan is to have a Bank Note one design or picture, with all the lettering interwoven in it. The whole to be engraved on the plate by the hand of the artist without the use of dies. A counterfeiter then would be obliged to do the work himself instead of employing others who do not know for what purpose their work is to be used.36

While the unit system was very effective in deterring counterfeiting, it was prohibitively expensive, and apparently only one U.S. bank adopted it.37

The quality of the paper used to make bank notes was another means of foiling counterfeiters. A U.S. treatise on counterfeit, altered, and spurious notes published in 1865 claimed that genuine notes had a “fine glossy surface,” while counterfeit notes typically had a “light, greyish” colour, were “soft to touch,” and “fuzzy.”38 To protect its notes from illegal duplication during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Bank of England relied on high-quality paper that carried a watermark and was made from linen rag. The Bank of England also tried to ensure that its circulating notes were always new and clean: they were never reissued when returned to the Bank for redemption. Consequently, in the 1880s, the average street “life” of a £5 note, then a large-value denomination, was as short as five days.39

The invention of calotype photography by William Henry Fox Talbot prompted further defensive improvements in bank-note design. Patented in 1841, calotype photography was vastly superior to the earlier daguerreotype process. Not only was the required exposure time reduced from about an hour to one minute, calotype photography produced a negative from which any number of positive (black and white) copies could be made. In contrast, daguerreotype photography produced only a single positive image.

The new technology was quickly adopted by counterfeiters, although bogus bills made in this fashion were judged inferior to notes produced using other techniques, such as lithography. Photographs of real notes did not feel like the genuine article, having a “smooth or varnished” texture, while the colour black turned out brown, or “dingy.”40

The advent of calotype photography sent shock waves through the North American banking community.41 People were advised not to accept any note printed solely in black and white. To test their validity, suspect notes were sometimes treated with “a solution composed of sixty grains of cyanide potassium [a deadly poison], in an ounce of pure water.” The solution would apparently “remove the photographic impression almost instantaneously,” but would not affect “the carbon ink of the bank-note-plate printer.”42

To protect notes from photographic counterfeiting, banks began to produce them in multiple colours. In 1856, Henry Bradbury, a British printer, designed anti-photographic printing in which portions of the note design were printed in one colour with an overlay of a different colour.43 A design element in red or green, such as the denomination of the note, was applied on top of the black image. The additional colour thwarted the circulation of simple photographs of notes, since the colour would be reproduced as a muddy black when copied using black and white photography.

The added colour also prevented the copying of notes using anastatic printing. In this process, invented in 1834 by Charles d’Aiguebelle of France as a means of replicating old prints,44 any oily image on paper could be transferred onto a metal plate, etched with acid, and duplicated.45 Since the coloured parts of a bank note would be transferred along with the underlying black design, these parts would turn out black when copied and could not be subsequently disguised with the addition of colour.

Unfortunately, counterfeiters discovered that the coloured elements could be removed using chemicals, leaving behind the black ink base image, which could then be acid-etched onto a metal plate either directly or via photography. Once the base image had been copied, the colours could be added back using a different plate for each colour. As a consequence, the multicoloured bank notes soon became extremely vulnerable to counterfeiting.

In 1858, the magazine Scientific American reported that George Matthews, a chemist employed by the Montreal City Bank, had taken out patents in both Canada and the United States for a chemical process to help deter photographic counterfeiting. “The discovery is of a calcined green oxyd of chromium, which produces a green tint, and this being mixed with the black carbon ink, produces an impression which is unalterable.”46 Experts “all testified to the perfect security afforded by the ‘patent green tint and black carbon ink.’” The magazine claimed all chemical tests failed to remove the green tint without damaging the underlying black impression and even the paper itself. Immediately, the green tint, called the “Canada Bank Note Printing Tint,” was adopted by security printers and note issuers in both Canada and the United States. The famous U.S. “greenback,” issued during the 1860s was printed using this green tint.

City Bank of Montreal, $1, 1851 and $1, 1857. The note issued in 1851 carries the removable red protector “ONE,” while on the note issued in 1857 the protector appears in the indelible green tint.

(National Currency Collection)

Interestingly, George Matthews was not the person who came up with the idea of using the chromium oxide tint. That honour apparently belonged to the American Dr. Thomas Sperry Hunt, at the time a professor of chemistry at Laval University.47 He developed the indestructible tint ink in response to an appeal by the President of the Montreal City Bank whose notes were being counterfeited. Unfortunately, at the time, only British subjects resident in Canada were eligible to apply for a Canadian patent. As a U.S. citizen, Hunt needed a Canadian intermediary to file the patent. George Matthews, a Montreal-based lithographer and engraver who was also an agent for a U.S. firm that would later become part of the American Bank Note Company, acted as his front man. The patent for the tint was granted on 1 April 1857 under Matthews’s name with the royalties being passed on to Hunt. Hunt went on to develop new indestructible tints, the patent for which he took out in his own name in 1863, having become a Canadian citizen. The Province of Canada’s 1866 series of notes were printed by the British-American Bank Note Company in Ottawa using one of Hunt’s secure green tints.48

Invented during the early nineteenth century by Asa Spencer, the geometric lathe was advertised as “a most important security against counterfeiting; not exceeded in value even by the artistic perfection of the vignettes, or portraits, and lettering.”49 It permitted bank-note designers to include extremely complex geometric forms, called guilloche, on the steel plates. These patterns resembled those made by a modern “Spirograph.” The complexity of guilloche was very difficult, if not impossible, to replicate by hand. Moreover, the geometric lathe was extremely expensive. In the late nineteenth century, the lathe used by the American Bank Note Company was said to cost $10,000 (more than $200,000 in today’s money) and took three years to build.50

The U.S. Civil War marked a turning point for bank notes and counterfeiting in the United States. Short of cash to pay for the war effort, the federal government asserted its constitutional authority over monetary affairs in 1861 and introduced a national currency—the “greenback.” The federal government subsequently enacted the National Bank Act, which effectively taxed the notes of state-chartered banks out of existence. To continue to issue bank notes, state banks had to become federally regulated national banks. National bank notes were of a standard size, denomination, colour, and design (other than the name, town, state, and charter number of the issuing bank) and were backed by holdings of U.S. government securities.51 Starting in 1877, all national bank notes were printed by the U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing, thus ensuring consistent note quality.52 Unlike notes issued by state banks, national bank notes were accepted at par throughout the country.

Guilloche “button.” Known as “guilloche” because they resembled braided ribbons, the complex, symmetrical patterns of fine lines created on the geometric lathe were a common security feature on most bank notes until recently.

(National Currency Collection)

United States, $1, 1862. Known as the “greenback,” for obvious reasons these non-convertible government notes were issued during the American Civil War.

(National Currency Collection)

The new national U.S. currency was almost immediately counterfeited, but the federal government was equally quick to respond. With the Civil War in full swing, counterfeiting threatened the financial health of the Republic and could not be countenanced. With state and local law enforcement agencies unable or unwilling to take on the counterfeiters, the federal government took matters into its own hands. In 1865, it founded the Secret Service, whose main objective was “to restore public confidence in the money of the country.”53

Interestingly, in 1864, just before the formal establishment of the Secret Service, U.S. Treasury officials captured the head of the Johnson clan of Lawrence, Indiana, virtually all of whose members were involved in counterfeiting. After cutting a deal with the U.S. authorities by informing on other counterfeiters, Johnson avoided trial.54 The clan was later to resurface in Canada, where they again took up the “family business,” as we shall see in chapter 6.

The adoption of an easily recognizable national currency, combined with robust law enforcement, brought an end to the heyday of the American counterfeiters. Although the counterfeiting of U.S. notes never again occurred on the scale reached before the Civil War, it remained a recurring problem. In 1880, The Globe reported that it had “reached such a perfection that the Treasury authorities are in despair,” and that the $100 national bank note would have to be withdrawn because of the quality of the counterfeits in circulation.55

The situation was somewhat better in Canada. The counterfeiting of Canadian bank notes, while a persistent headache for merchants, banks, and law enforcement agencies, had never been as prevalent as the counterfeiting of U.S. bills. As already noted, this mainly reflected the relatively small number of issuing banks whose notes were well known throughout the country. Nevertheless, the failures of the International Bank and the Colonial Bank in late 1859 led to growing criticism of lax banking regulations. While these “wildcat” banks had offices in Canada, they circulated notes primarily in the United States. In his 1910 authoritative review of Canadian banking, Roeliff Breckenridge wrote, “No great loss was caused the Canadian public by their collapse, but the scandal and the ease of acquiring dangerous privileges which had led to the scandal, called forth bitter and general complaint.”56 In 1863, two more banks had their charters repealed for intending to defraud the public. The Bank of Clifton (formerly the Zimmerman Bank) “had pretended to redeem or to cash its notes in Chicago,” while the Bank of Western Canada, owned by a tavern keeper, “sought to float its issues in Wisconsin, Kansas, and Illinois.”57

Such banking scandals contributed to pressure for a national Canadian currency. In 1866, amid considerable controversy, the government passed the Provincial Notes Act, allowing for the issue of up to $8 million in legal tender notes. Following Confederation the next year, such Provincial notes became Dominion notes. In 1869, the new Dominion government attempted to introduce a National Bank Act, styled after similar U.S. legislation. As was the case in the United States, it proposed that Canadian banks would issue a standardized currency, backed by government bonds. Although the Bank of Montreal and the Bank of British North America supported the proposal, other banks were opposed. They favoured the prevailing system where each bank issued its own notes backed by the general assets of the bank. Opposition in Parliament to the draft legislation was overwhelming and included many government members. With the resignation of Finance Minister Sir John Rose, who had sponsored the proposed legislation, the act, which would have recast the Canadian financial system along U.S. lines, was dropped.58 The introduction of a standard Canadian currency would have to wait until the establishment of the Bank of Canada in 1935.

Bank of Clifton, $5, 1859. An early Canadian chartered Bank, the Bank of Clifton became a wildcat bank and failed in 1859. It issued large quantities of notes throughout the U.S. Midwest with no intention of redeeming them.

(National Currency Collection)

International Bank of Canada, $20, 1859. Another wildcat bank.

(National Currency Collection)

Province of Canada, $1, 1866. Canada’s first government note issue.

(National Currency Collection)

GREEN GOODS FOR SALE

Counterfeiting scams claimed many victims during the late nineteenth century. Circulars advertising counterfeit notes for sale were sent by mail, typically from the United States, to prospective buyers in Canada. In 1893, such a “confidential” circular sent from New York was widely distributed in Ontario. Its recipients included a leading Canadian cabinet minister, as well as Mr. E. B. Eddy, the millionaire lumberman.59 It invited people in Ontario to buy counterfeit U.S. bank notes and purported to offer $1,000 in bogus bills for $300. The Globe newspaper reported that one Toronto woman mortgaged her home to raise the minimum $300 needed.

She was not alone. There were many takers, despite the fact that replying to such circulars was a felony under the Criminal Code of Canada, incurring a penalty of up to five years in the Kingston Penitentiary. Unfortunately for prospective buyers, once the scam came to the attention of the authorities, the Post Office forwarded their letters to Major Sherwood, commissioner of the Dominion Police. Sherwood received scores of such letters and, according to The Globe, he “has in his keeping the liberty of every man who wrote one.”

Such scams apparently increased in frequency around events that might attract people to New York. The circulars would invite buyers to purchase the bogus notes in a face-to-face exchange. The scam’s victims would be shown genuine bills as examples of the counterfeits to be purchased, and an exchange would be made. However, the credulous buyers were duped, receiving a parcel of sawdust rather than the promised notes. Many had the temerity to complain, writing to the circular’s New York address. These letters also were redirected to Major Sherwood. One Canadian victim wrote, “The money you got from me I was saving for my motherless children, my poor orphans.” An angry woman called “down all the curses of heaven because she had not been able to swindle her neighbours by receiving counterfeit money.” One man complained of receiving worthless Confederate notes. The Globe concluded, “In reading the letters sent by scores of simpletons to the swindlers, who are growing rich on the credulity and avarice of their victims, one cannot help exclaiming, ‘What fools these mortals be.’”

Eight years later, the scam was still sucking in victims. Homer R. Harris, a young farmer from Kinloss Township, Ontario, was arrested in November 1901 for attempting to buy counterfeit money in response to a circular from New York advertising “green goods for sale.”60 His letter to the swindlers requesting their terms for the purchase of counterfeit fives and tens rather than the usual ones and twos, so that he could have a “quicker return,” was redirected to provincial detective J. E. Rogers. Impersonating the sender of the circular, Rogers arranged to meet Harris at the Queen’s Hotel in Palmerston, Ontario, where the hapless soul was arrested. It seems Harris wanted to make enough money to take a singing course. Since he didn’t like farming, he wanted a stage career!

COINING IT

“One of these dollars is a counterfeit, ma’am.”

“How can you tell?”

“Simply by sound. Just tap it and hear how clear the genuine sounds. That’s tenor. Notice when I tap the other one. That’s base.”61

Although the forging of bank notes stole the limelight during the nineteenth century, the counterfeiting of coins remained a popular choice for small-time fraudsters. Using moulds made from genuine coins, counterfeiters would make copies using various alloys of base metal. Alternatively, they might coat a base metal plug with a wash of precious metal. Some enterprising thieves split gold coins edgewise, replaced the precious core with a cheap substitute, and resealed them. The problem, however, was to replicate the feel and the heft of genuine coins. Counterfeits made from aluminum alloys were typically too light and felt oily or greasy. Some counterfeiters made full-weight coins using precious metals, profiting solely from the small difference in the value of the metal and the face value of the coin (seigniorage) that would have otherwise gone to the government.

Early in 1885, counterfeit Canadian and U.S. silver dollars, half dollars, and quarters appeared in Windsor and Essex County. Suspicion fell on a Mrs. Harris, “a well-preserved woman of forty,” who had known connections with area counterfeiters; her brother being in Kingston Penitentiary for “shoving the queer.” When Hattie, Mrs. Harris’s sixteen-year-old daughter, was caught trying to pass a fake half-dollar coin at Davenport House, a local tavern, she told police that she’d received it from a wealthy lumber dealer called Hall. Police arrested both mother and daughter after a search of their home revealed newly coined bogus American half dollars and quarters. Hall was also arrested when he was found to be carrying $3.50 in counterfeit coins; more was uncovered in his nearby hotel room. He was subsequently released on $300 bail.62 The outcome of their trial is not known.

Counterfeit of a 1929 fifty-cent piece and the moulds used to make it.

(National Currency Collection)

Two years later, David White was tried for passing a counterfeit fifty-cent piece. In court, White’s lawyer denounced the policeman for having “defaced the Queen’s money” in his attempt to ascertain its provenance. In an effort to determine whether the coin was genuine or bogus, the magistrate bounced it on his desk and then dropped it on the floor. Unable to decide, he dismissed the case against White, but the Court decided to keep the dubious coin.63

The counterfeiting of Canadian coins fell off significantly during the twentieth century as the use of precious metal was discontinued in the production of small change. The last coins minted for general circulation in Canada that contained silver were issued in the 1960s. Nevertheless, the incentive to counterfeit coins made of base metals emerges from time to time, particularly when metal prices are low. During the Great Depression, counterfeit one-cent pieces were reported to be circulating in Vancouver!64

ENDNOTES FOR CHAPTER FOUR

1C. S. Howard, “Canadian Banks and Bank-Notes: A Record,” The Canadian Banker, Canadian Bankers Association, 1950, 3.

2J. L. Brooke, The Refiner’s Fire: The Making of Mormon Cosmology, 1644–1844 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 115. See also Mihm, A Nation of Counterfeiters, 30.

3New York Times, “Counterfeiting, Statistics of Frauds on Our Paper Currency,” 30 July 1862. See also W. E. Weber, “Early State Banks in the United States: How Many Were There and Where Did They Exist?” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review 30, no. 2 (2006).

4J. T. Holdsworth, National Monetary Commission, vol. 4, The First Bank of the United States (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1910), 52.

5Bank notes also traded at a discount from face value, the size of which depended on how far the note was from the bank’s note-redemption office.

6New York Times, “Counterfeiting Statistics,” 30 July 1862.

7Ibid.

8E. J. Wilber and E. P. Eastman, A Treatise on Counterfeit, Altered, and Spurious Bank Notes (Poughkeepsie, NY: published by the authors, 1865), 22. See also Mihm, A Nation of Counterfeiters, 272.

9New York Times, “Startling Revelations in Counterfeiting,” 19 October 1852.

10Howard, “Canadian Banks and Bank-Notes,” 13.

11Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, “Fun Facts about Money, Counterfeit Currency,” 2011, http://www.frbsf.org/federalreserve/money/funfacts.html#A2.

12Mihm, A Nation of Counterfeiters, 8.

13A. M. Davis, National Monetary Commission, vol. 5, The Origins of the National Banking System (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1910), 25.

14New York Times, “Counterfeiting Statistics,” 30 July 1862.

15G. B. Tremmel, Counterfeit Currency of the Confederate States of America (Jefferson, NC; London: McFarland & Co., 2003), 37, 45.

16Cooley, Currency Wars, 128–29.

17Mihm, A Nation of Counterfeiters, 328.

18J. Powell, History of the Canadian Dollar (Ottawa: Bank of Canada, 2005), 14.

19The Canada Banking Corporation was established by a group of merchants in Montreal in 1792. However, it is unclear whether this bank ever opened for business.

20A. Shortt, “Currency and Banking 1760–1841,” In Canada and Its Provinces: A History of the Canadian People and Their Institutions by One Hundred Associates, ed. A. Shortt and A. Doughty, vol. 4, 599–636 (Toronto: Glasgow, Brook & Co., 1914), 610.

21The first Bank of Upper Canada, located in Kingston, operated without a government charter and was declared illegal. It closed in 1822.

22R. M. Breckenridge, “Free Banking in Canada,” Journal of the Canadian Bankers Association 1, no. 3 (1894): 154–66.

23Breckenridge, The History of Banking in Canada, Appendix IV.

24Mihm, A Nation of Counterfeiters, 211.

25The Globe, “Extraordinary Case,” 9 September 1859.

26The Globe, “The Counterfeit Bill Case,” 10 September 1859.

27Both the International Bank and the Colonial Bank failed just weeks later, owing to their own fraudulent banking practices.

28The Globe, “The Counterfeit Bill Case,” 12 September 1859.

29Ibid.

30The Globe, “The Counterfeit Bill Case,” 13 September 1859.

31Mihm. A Nation of Counterfeiters, 222.

32The Globe, 20 March 1858.

33Philotechnus, The Balance and Columbian Repository, vol. 5, An Examination of the Method of Making Bank Bills from the Stereotype Plate (Hudson, NY: Harry Croswell, 1806), 92.

34See R. G. Doty, Pictures from a Distant Country: Images on 19th Century U.S. Currency (Raleigh, NC: Boson Books, 2004), 13–14. See also W. H. Griffiths, Ninety Years of Security Printing: The Story of British-American Bank Note Company Ltd., 1866–1956 (Ottawa; Montreal: British American Bank Note Company, 1956).

35Philotechnus, An Examination, 92–93.

36W. L. Ormsby, Letter to Franklin Pierce, 31 January 1853, http://currency.ha.com/c/item.zx?saleNo=338&lotIdNo=81027.

37Mihm, A Nation of Counterfeiters, 299.

38Wilber and Eastman, A Treatise on Counterfeit, 19.

39de Fraine, Servant of This House, 5.

40New York Times, “Bank Note Counterfeiting,” 28 February 1856.

41Mihm, A Nation of Counterfeiters, 300.

42New York Times, “Photographic Counterfeiting,” 27 December 1856.

43Classic Encyclopedia, based on the 11th Edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1911, http://www.1911encyclopedia.org/Bank-notes.

44Anastatic Process of Lithography, Photo Conservation, 2012, http://www.photoconservation.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=101:anastatic-process-of-lithography&catid=35:printprocesses&Itemid=63.

45P. de la Motte, On the Various Applications of Anastatic Printing and Papyrography (London: David Bogue, 1849).

46Scientific American, “Important Improvement in Bank Note Printing,” 24 July 1858, 368.

47W. Jacobs, “Canada Land of the Greenbacks,” Mid-Island Coin Club Journal (September 2007), http://www.rightclickhome.com/Numis/micc/09Sep2007/Canada,%20Land%20of%20the%20Greenbacks.htm.

48Ibid.

49C. W. Dickenson, “Copper, Steel, and Bank-Note Engraving,” Popular Science Monthly (March 1895): 597–613.

50Ibid., 613.

51Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, History, 2011, http://www.occ.gov/about/what-we-do/history/OCC%20history%20final.pdf.

52Mihm, A Nation of Counterfeiters, 364.

53P. H. Melanson with P. F. Stevens, The Secret Service: The Hidden History of an Enigmatic Agency (New York: Carroll & Graf, Publishers, 2002), 3.

54Ibid., 10.

55The Globe, “Extensive Counterfeiting,” 28 June 1880.

56Breckenridge, The History of Banking in Canada, 71.

57Ibid., 71.

58Breckenridge, The History of Banking in Canada, 97–99. See also B. H. Beckhart, The Banking System of Canada (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1929), 376–78.

59The Globe, “Green Goods Sharks,” 26 April 1893.

60The Globe, “Tried to Buy Bad Money,” 26 November 1901.

61The Globe, 12 January 1884.

62The Globe, “Alleged Counterfeiters, a Wealthy Lumber Dealer Arrested at Windsor,” 22 January 1885.

63The Globe, “There Was a Jingle of Silver at the Police Court Yesterday,” 16 June 1887.

64The Globe, “The Strangest Story of the Depression,” 20 August 1935.