LARISSA BONFANTE

Around 630 B.C.E. an ambitious Etruscan couple arrived in Rome in a covered wagon. As the man and his highborn wife looked down on the city that was to be their new home, an eagle came down and plucked off the husband’s hat and flew back into the sky above the covered wagon; then swooping back down to put the hat back on the man’s head, the eagle disappeared into the heavens. The wife, who, like most Etruscans, was skilled at reading omens, joyfully embraced her husband, explaining this event as a sign from the gods that their highest ambitions would be fulfilled. The prophecy came true. Lucius Tarquin became king of Rome and founder of the Tarquin dynasty. His wife was the powerful Etruscan queen, Tanaquil.

Half a century later, another Tarquin became king after killing his royal father-in-law, urged on by his wife, who drove her carriage over her own father’s corpse. As the Roman historian Livy tells the story (1.48.5–7),

All agree that she drove into the forum in an open carriage in the most brazen manner, and calling her husband from the Senate House, was the first to hail him as king. Tarquin told her to go home, as the crowd might be dangerous. [On the way the driver] pulled up short in sudden terror and pointed to [her father’s corpse] lying mutilated on the road. There followed an act of bestial inhumanity—history preserves the memory of it in the name of the street, the Street of Crime. The story goes that the crazed woman … drove the carriage over her father’s body. Blood from the corpse stained her clothes and spattered the carriage, so that a grim relic of the murdered man was brought by those gory wheels to the house where she and her husband lived. The guardian gods of that house did not forget; they were to see to it, in their anger at the bad beginning of the reign, that as bad an end should follow.

(Sélincourt 1960)

This last king of Rome, Tarquin the Proud, ruled by fear. His son’s rape of the Roman matron Lucretia put an end to the monarchy at Rome. It all started when a drinking party among inactive officers culminated in a contest of wives, for which the men all rode out into the night. They found Lucretia busily directing the women of her household in wool-working. The Etruscan princesses, in contrast, were attending a luxurious dinner party, together with other “beautiful people” of their rank. At the house of Lucretia, Sextus Tarquinius, intrigued and then obsessed by Lucretia’s beauty and chastity, returned later to threaten her life and to violate the laws of hospitality as her guest by raping her. The Etruscan tyrants were, as a consequence, driven from Rome, and the Roman Republic was established.

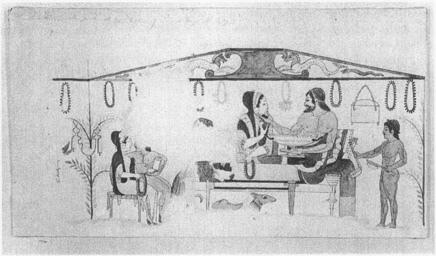

The traditional tales of the Etruscan dynasty at Rome and the events leading up to the rape of Lucretia emphasize the importance of the Tarquins’ wives in acquiring the kingship for their husbands, and, along with the stated contrast with the Roman matron Lucretia—who killed herself to preserve her honor and that of her family—dramatically illustrate the different social roles of Etruscan and Roman women. Handed down by tradition and vividly related by Livy, these Roman stories of Etruscan queens seem to reflect elements of local Etruscan customs, many of which agree with what we learn about the Etruscans from the considerable evidence of archaeology. Wall paintings from Tarquinia show luxurious banquets attended by beautifully dressed nobles, men and women together. On a wall painting (Fig. 8.1) from the Tomb of the Painted Vases in Tarquinia, for example, we see a couple served by a small slave, while the husband fondly touches his wife’s chin. On the wall hang the lady’s necklaces and toilet box (cista) along with the usual flower wreaths. Here and elsewhere, women take their places by the men, equal in family lineage. The importance of the married couple, rather than the adult male citizen as in Athens or the paterfamilias in Rome, is clearly shown in the monuments (see Fig. 8.7). This reflects the aristocratic society of the Etruscans, a society in which public and private life were much less differentiated than in contemporary classical societies. All the evidence points to the fact that the lives of upper class Etruscan women, in the Archaic period—especially seventh to fifth centuries—had an element of autonomy and privilege surprising in comparison to that of other women in the ancient Mediterranean world.

Figure 8.1. Drawing of a wall painting showing a couple banqueting on the same couch, from the Tomb of the Painted Vases in Tarquinia (ca. 500 B.C.E.). Her light skin and his dark color, as in Greece, depict gender difference, but here, unlike Greece, where women shown in symposia are prostitutes, the woman is a properly dressed wife: a married couple are shown attending a banquet together.

Perhaps no feature of Etruscan society differed so much from that of Greece and Rome as the position of women. Recently, much serious study of Etruscan women has been done, stimulated in part by the attention paid to Greek and Roman women. Scholars no longer focus on Bachofen’s nineteenth century thesis of an Etruscan matriarchy, nor even on the figure of Tanaquil, recently explained in a historical and religious context. New fields of study include an examination of the religious titles of women, of the types of objects typically found in women’s tombs, of women’s chariots, of women’s jobs. Women’s graves of the ninth and eighth centuries B.C.E., for example, contained spinning and weaving equipment, special shapes of tableware, jewelry, belts, and other objects of personal adornment, maybe even including perfume. There were large quantities of amber, prized for its beauty and magic properties: women apparently best knew how to handle the magic powers of amber, just as Tanaquil could read the meaning of bird signs and, in the North, women could read the magic signs of the runes (so the name Gudrun, “good at reading runes”). (Rallo 1989; Bonfante 1985: 287).

In judging this aspect of Etruscan life, as in others, we are limited by the lack of any Etruscan literature. What we have are the accounts of Greek and Roman historians, all of them extremely biased against what they perceived to be Etruscan immorality and self-indulgence. The evidence of inscriptions—some 13,000 inscriptions have come down to us—must be interpreted, and so must the monuments. Modern scholars tend to be more comfortable with literary evidence than with the monuments, but the monuments in fact speak to us more directly than does the literature.

For example, the bronze women’s mirrors decorated with engraved designs demonstrate that literacy, considerably more widespread in Etruria than elsewhere, and important for religious reasons in all of central Italy, was not confined to men; out of some 3000 mirrors, more than 300 (or 10 percent) are provided with inscriptions, mostly identifying mythological scenes. The example illustrated (Fig. 8.2) shows a loving couple, Turan (Aphrodite) and Atunis (Adonis), a typically Etruscan scene involving an older woman and a younger man. The fringes on the shoulders of Turan and her attendant are a sign of divine status or of the high rank of a mortal. The inscription on Athena’s shield says that Tite Cale gave the mirror to his mother as a gift. These mirrors, like the richly decorated tombs of women and men, were for the elite; only 2 percent of the tombs at Tarquinia had painted decoration.

Figure 8.2. Bronze mirror engraved with a scene of Turan (Aphrodite) and Atunis (Adonis) as lovers. The classical, solemn style is typical of Etruscan art in the second half of the fourth century B.C.E.

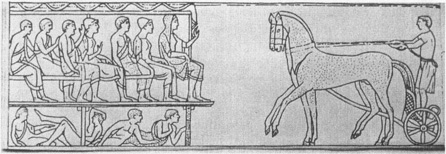

Women’s tombs were as richly furnished as those of the men; in the early period a few even had chariots buried with them. In the Tomb of the Five Chairs, enthroned male and female ancestors protected the family with their divine status. A tomb painting from Chiusi (Fig. 8.3) shows funeral games and entertainments being performed in honor of a deceased woman, seated, with footstool and parasol—a close parallel to a scene of honors paid to a dead man in the Tomb of the Juggler at Tarquinia. In the tombs the houses of the living were reproduced for the dead, with all the equipment for eating, drinking, and dancing, as well as wall paintings depicting these feasts. Etruscan married couples took part in banquets, in contrast with the men’s symposia or drinking parties so popular in Greek life and vase painting; at those Athenian parties only female entertainers and prostitutes were welcome (Fig. 10.1). The rock-cut tombs at Cerveteri reproduce the rooms of an Etruscan house, with doors, windows, chairs, and beds. In the bedrooms the men’s and women’s beds have different shapes. Jacques Heurgon (1961) pointed out that both types of beds are in fact shaped like normal banquet couches, but that those of the women are encased in house-shaped containers, with pointed “pediments” at the head and foot of the beds. Outside, stone markers showed who was buried in the chamber tombs: phallusshaped for men, house-shaped for women. Gifts left with dead women consisted of spindle whorls, spools and other wool-working equipment, mirrors and toilet boxes and jewelry, including amber and other “magic” items to ward off the evil eye, and special shapes of jugs and banquet equipment. The splendid dresses in which the women were buried have, of course, been lost to us, but the symbolic and precious nature of their possessions showed their status. Men took with them their armor and their bronze bowls, imported Greek vases and black cups they had used to entertain their numerous guests and show off their status in their lifetime. Later, Hellenistic funerary reliefs show the couple renewing their vows, each spouse followed by attendants. Throughout, the archaeological record seems to express women’s high social status along with the distinction in function between them and their men.

Figure 8.3. Painting from the tomb of the Monkey at Chiusi, late sixth century B.C.E., with the deceased woman watching funeral games in her honor.

Etruscan monuments and the evidence of language and inscriptions thus confirm many of the claims of Greek and Roman authors, though obviously their accounts also contain contemporary clichés concerning barbarians and their luxurious lusty lives, as well as hostility toward an Etruscan way of life that differed so much from their own. Experiencing their difference as a conflict in civilization, Greek and Roman authors expressed it in terms of attitudes to sex and relations between women and men.

The longest ancient literary passage we have about Etruscan customs comes from Theopompus, a Greek historian of the fourth century B.C.E. He was startled by them and drew the worst possible conclusion from what he saw and heard about Etruscan women (the passage is quoted in a work by Athenaeus, a later Greek author).

Among the Etruscans, who were extraordinarily pleasure-loving, Timaeus says … that the slave girls wait on the men naked. Theopompos, in the forty-third book of his Histories, also says that it is normal for the Etruscans to share their women in common. These women take great care of their bodies and exercise bare, exposing their bodies even before men and among themselves: for it is not shameful for them to appear almost naked. He also says they dine not with their husbands, but with any man who happens to be present; and they toast anyone they want to.

And the Etruscans raise all the children that are born, not knowing who the father is of each one. The children also eventually live like those who brought them up, and have many drinking parties, and they too make love with all the women.

It is no shame for the Etruscans to be seen having sexual experiences … for this too is normal: it is the local custom there. And so far are they from considering it shameful that they even say, when the master of the house is making love, and someone asks for him, that he is “involved in such and such,” shamelessly calling out the thing by name.

When they come together in parties with their relations, this is what they do: first, when they stop drinking and are ready to go to bed, the servants bring in to them—with the lights left on!—either hetairai, party girls, or very beautiful boys, or even their wives.

When they have enjoyed these, they then bring in young boys in bloom, who in turn consort with themselves. And they make love sometimes within sight of each other, but mostly with screens set up around the beds; these screens are made of woven reeds, and they throw blankets over them. And indeed they like to keep company with women: but they enjoy the company of boys and young men even more.

And their own appearance is also very good-looking, because they live luxuriously and smooth their bodies; for all the barbarians living in the West shave their bodies smooth.… They have many barber shops.

(Gulick 1927–41: 12.517–18)

Athenaeus also quotes the remark of Aristotle (Gulick 1927–41: vol 1, p. 103) that Etruscans eat with their wives, reclining at table with them under the same blanket; and that Etruscan slaves are very beautiful and dress better than is the custom of slaves.

Theopompus’s picture is put together in part from a literary cliché about the luxurious life of the barbarians, in this case the Etruscans; but it is perhaps also based on reports of Greek travelers in Etruria. All the standard charges of luxurious living (Greek, truphe) are present: the lust, the nudity, the homosexuality, the parties, the fancy barbers. How much of his account was true? Certainly the extraordinary freedom of the women, emphasized by the implied contrast with Greek women of the time, was more than simply the expression of the author’s hostility to a way of life vastly different from his own. So, for example, in a Greek trial in Athens, ca. 400 B.C.E., the orator Isaeus could prove in defense of his client that a woman was a courtesan who gave herself to anyone, rather than the man’s wife, by citing the evidence of neighbors who testified to the quarrels, serenades, and frequent scenes of disorder that took place when the woman was at the man’s house. These were proofs that she was a mistress and not a wife. For, he says, “no one, I presume, would dare to serenade a married woman, nor do married women accompany their husbands to banquets or think of feasting in the company of strangers, especially mere chance comers,” (Isaeus 3.14; Forster 1983)

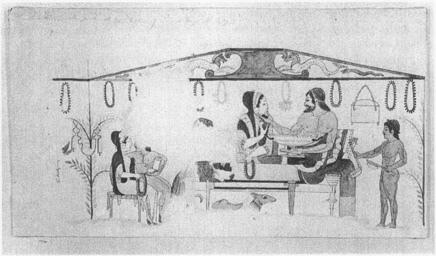

A Greek of Theopompus’ time felt a deep distaste for the Etruscan custom of the mingling of the sexes at dinner in a respectable context. Seeing husbands and wives so unexpectedly together was such a serious breach of Greek culture and good manners that it must have led Theopompus to imagine that women joined men in another traditionally male place, the gymnasium, where Greek men exercised naked. In fact, Etruscan women did attend games, as we see in paintings and reliefs from Tarquinia from the fifth century, B.C.E. (Fig. 8.4), showing bleachers with spectators, male and female, watching games and contests. But there is no evidence that they were particularly fond of such strenuous physical exercise as Spartan women are said to have practiced—like their husbands, they seem to have preferred spectator sports, though images of women athletes do occur in their art.

Etruscan women may well have raised their own children; here we can only guess at the reality behind Theopompus’s statement. Perhaps the ancient custom of infanticide, prevalent in both Greek and Roman societies (but not among the Hebrews and later forbidden by the Christians), was not present among the Etruscans. Their wealth may have made it less necessary, of course, though economic reasons are not necessarily in the foreground in such decisions. Another possible interpretation is that the women were said by Theopompus to raise their own children because legally they could decide what babies were to be brought up and which exposed—unlike Greece and Rome where legally it was the father who “raised up” the baby, acknowledging it as his own and therefore legitimate and a citizen. Etruscan art, in fact, much more than Greek art, and even before the Hellenistic period, focused on scenes of children, often with their mothers or their families.

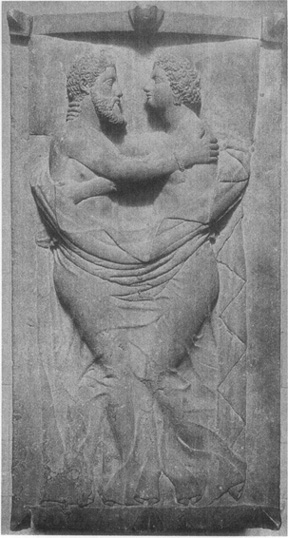

Much more easily confirmed is Aristotle’s remark that the Etruscans eat with their wives, reclining at table with them under the same blanket, and that their house servants, who were very beautiful, dressed better than was the custom of slaves elsewhere in the Classical world. Sarcophagi and tomb paintings often represent deceased couples joined together on their funeral beds as on their banquet couches during their lives. Best known, perhaps, are the terra-cotta sarcophagi from Cerveteri (in Rome and Paris) with figures of husband and wife, with archaic smiles, tenderly embracing (Fig. 8.5): the sarcophagi of “Bride and Groom,” as they are usually called in English (they actually represent a married couple, sposi in Italian), and the many couples at the happy feasts painted on the walls of tombs at Tarquinia. The blanket mentioned by Aristotle was, like a bridal veil today, long a symbol of the bride as well as of marriage. On the well-known sarcophagus of the Bride and Groom from Cerveteri, now in Rome, the mantle of the husband that covers the legs of the wife is not visible in our illustration. A depiction of a wedding on a relief from Chiusi (Fig. 8.6) shows the bridal pair under a fringed canopy, together with the priest, in a ritual remarkably like a traditional Jewish ceremony in modern America. And the typical gesture of the wife in Etruscan, as in Greek art, shows her holding the veil or mantle away from her face. Two other Etruscan couples are shown in bed together under the same blanket on sarcophagi from a later period. One shows husband and wife, idealized as classically young and beautiful and naked (Fig. 8.7). To have them both naked would have been a most unusual situation in Greece, where nudity was customary for men, but identified women as prostitutes; it is understandable in an Etruscan context, where the women enjoyed great privilege, perhaps even comparable to that of men.

Figure 8.4. Copy of a wall painting from the Tomb of the Chariots (Tomba delle Bighe) at Tarquinia, fifth century B.C.E., with men and women seated together on bleachers, watching games and contests.

Figure 8.5. Terra-cotta sarcophagus of a husband and wife from Cerveteri of the sixth century B.C.E., showing the couple on their couch. The Archaic Ionic style of the figures shows the Etruscans’ skillful use of this international style in this influential period of their history, when they provided important models for Roman art, religion, and culture.

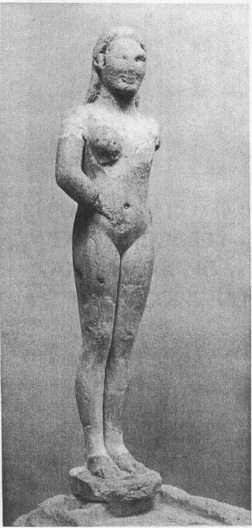

Similarly, the Etruscans had commissioned a naked cult statue of a goddess in the sixth century B.C.E. for a sanctuary at Orvieto (Fig. 8.8); the naked statue of the so-called Cannicella Venus was found in a sacred area within the necropolis of Cannicella at Orvieto, the ancient sanctuary of Volsinii. This highly unusual commission had gone to a Greek sculptor used to making naked statues of kouroi, male youths, around 530 B.C.E.—the statue was made of island marble and carefully repaired in antiquity. Several centuries earlier than Greek representations of nude goddesses in monumental form, the Etruscan goddess suggests again a different attitude to gender and the body.

Figure 8.6. Limestone relief from Chiusi, ca. 500 B.C.E., showing a wedding, the couple with a priest under a canopy and musicians playing in celebration. Again, the theme of the married couple shows how important this subject was in aristocratic Etruscan society.

Etruscans, even slaves according to Aristotle, dressed luxuriously by Greek and Roman standards. Athenians called certain luxurious ladies’ sandals with gold laces “Etruscan.” (Ehrenberg 1943: 278, citing Kratinus 131.) The Romans adopted Etruscan rounded mantles as their citizen’s normal toga, as well as their purple and bordered garments for triumphal garb, and for children, priests and magistrates. Etruscan women were usually represented with mantles and shoes, indicating that they went outdoors as much as the men—in contrast to the women of Athens, usually shown on vases of the Archaic and Classical periods at home, wearing the chiton (or, if courtesans “on the job” at drinking parties, naked).

The women we have been discussing were, of course, all of them members of the elite, the aristocracy. But the wealth of archaeological evidence from pre-Roman Italy allows us to see something of the religion and beliefs of the more humble. Votive figures from Italian sanctuaries reflect the private cults of the modest and poor. Healing sanctuaries with thousands of votive terra-cotta and bronze figurines have been found, testifying to the devotion of those who came there. In the seventh and sixth centuries, votive offerings consisting of a group of these bronze statuettes—a male figure, often a warrior, a female figure, and an animal statuette—are probably not divinities but a family unit, a household: the married couple accompanied by an animal representing their property. This type of votive offering was popular in north Etruria and was widely exported around Europe. Some sanctuaries, evidently the ancient equivalent of fertility clinics, specializing in women and children, received thousands of votive statuettes from worshipers asking for the procreation or protection of children or thanking the divinity for favors received. Many of the faithful gave so-called anatomical ex-votos, tiny models of uteri or breasts. But the majority of ex-votos consisted of swaddled babies or mothers and children, including mothers nursing their babies. This theme of the nursing mother (or kourotrophos) is all but completely absent from Classical art of mainland Greece and the world of the Greek islands and Asia Minor. This remarkable contrast reflects profound differences between Greek art and thought and that of the Etruscans and other peoples of ancient Italy, since figures of nursing mothers were popular all over Italy in Etruscan, south Italian, and Sicilian art, in regions where the concept of mother goddesses ruling over fertility and the birth of children had never ceased to be important.

Figure 8.7. Lid of a limestone sarcophagus of the mid-fourth century B.C.E., from Vulci, a couple recline together as if on their marriage bed. Their nudity and the idealization of the bodies suggests their closeness in the marriage bond.

Figure 8.8. The “Cannicella Venus,” (ca. 530 B.C.E.) cult statue of a nude goddess, the Etruscan Venus, from the Cannicella necropolis Orvieto (ancient Volsinii).

Images of nursing mothers were particularly frequent in the art of the fourth to the first centuries B.C.E.; they were votive gifts in sanctuaries where different languages were spoken, but geographical proximity, religious customs, and cultural influences formed a common bond among different peoples in central and southern Italy. While the image of the mother (often seated) was adopted from Greek art, the baby was a purely Etruscan addition (Fig. 8.9).

Figure 8.9. Votive terra-cotta figurines of mothers with infants and young children on their laps, a subject almost nonexistent in Greek art but common in the art of Italy from early times. There are numerous examples of these mold-made figures, the ones illustrated here come from the fourth century B.C.E., Satricum.

Was a religious reason enough to account for the importance of the motif of mother and child in the art of ancient Italy, or did the culture include a special affection for children, as was apparently the case in ancient Egyptian society? Historical changes in attitudes and family feelings, as well as family structure, are currently debated by scholars. Certainly affection between husband and wife was shown openly in Etruscan art (we are reminded of Theopompus’s shocked description of the servant reporting that the master is in bed, presumably with his wife), much more openly than in Greece or other Mediterranean societies where it is still considered improper to exhibit conjugal love in public, or even to speak of it. Several loving couples are shown in which one of the partners is affectionately chucking the other under the chin (Fig. 8.1), and we could suggest that the nursing-mother images also signify special familial bonds as well as religious symbolism.

At the beginning of this chapter, we saw some formidable Etruscan women at home and abroad, together with their husbands and with their families. There is also tantalizing evidence about Etruscan women’s relations with one another. We see women working together at textile production on a seventh-century object decorated in Etruscan style, a bronze axe-shaped pendant from a rich woman’s tomb in Bologna (Fig. 8.10); its relief decoration shows women at work carding, spinning, and weaving. Sixth-century wine-jugs of black bucchero, a typically Etruscan pottery fabric, show groups of running naked girls, perhaps reflecting some ritual initiations of young girls into adulthood. Elsewhere, two women are shown traveling together in a carriage on sarcophagus reliefs as well as, apparently, on a sixth-century terra-cotta relief plaque from a building at Murlo, near Siena. Two women are represented enthusiastically (romantically?) embracing in a scene on an engraved mirror.

Figure 8.10 Drawing of the front and back of a seventh-century B.C.E. bronze pendant found in the tomb of a woman in Bologna. The reliefs include important women seated on thronelike chairs working wool in the same demonstration of feminine domesticity seen in Greek and Roman art.

Like art, language preserves traces of women’s lives and their importance in Etruscan society. Funerary inscriptions give evidence of women’s names. Roman women had no names of their own; they were known first as their fathers’ daughters and later as their husbands’ wives, when they came into the husband’s manus, or legal power, as in the legal formula of marriage, ubi tu Gaius, ego Gaia (as you are Gaius, I am Gaia). Etruscan women had their own names—Tanaquil, Seianti. They apparently passed their rank to their children; the frequent use of both the father’s name and the mother’s name in Etruscan inscriptions attests to the mother’s importance. The name of Seianti Hanunia Tlesnasa is inscribed on a brightly painted sarcophagus in the British Museum (Fig. 8.11). The dowager herself appears on the cover, mirror in hand, holding out her veil and wearing all her precious jewelry. That she lived to be more than eighty years old is shown by an analysis of her bones, still inside the casket after all these years. Scientists have reconstructed her face, so we can see what one of the last of the great Etruscan ladies looked like. Soon after her death, the sophisticated, luxurious, aristocratic Etruscan culture, in which women enjoyed the kind of status associated elsewhere only with men, disappeared into that of the victorious Romans.

Figure 8.11. Painted terracotta sarcophagus (ca. 150 B.C.E.) of a woman named Seianti Hanunia Tlesnasa, showing the richly bejeweled figure of the deceased reclining on the lid as on her banqueting couch. Her gesture, pulling the veil from her face, is common for brides and wives.

Cary, E. 1937. Dionysius of Halicarnassus: Roman Antiquities. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Mass.

Forster, E. S. 1983. Isaeus. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Mass.

Gulick, C. B. 1927–41. Athenaeus: Deipnosophistae. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Mass. vol 6 (rev. 1955)

Sélincourt, A. de. 1960. Livy: The Early History of Rome. Books 1–5. Harmondsworth, Middlesex.

Bachofen, J. J. 1967. Myth, Religion and Mother Right. Princeton, N.J. (Originally published 1861 and 1870)

Bartoloni, G. 1989. “Marriage, Sale and Gift. A proposito di alcuni corredi femminili dalle necropoli populoniesi della prima età del ferro,” 35–54 in Le Donne in Etruria ed. A. Rallo, Rome.

Bianchi Bandinelli, R. 1982. L’arte etrusca. Rome.

Bonfante, L. “Etruscan Couples and their Aristocratic Society.” in Reflections of Women in Antiquity, edited by Helene P. Foley, 323–43. New York.

Bonfante, L. 1984. “Dedicated Mothers.” In Visible Religion, 3: 1–17. Leiden.

———. 1985a. “Amber, Women and Situla Art.” Special issue of Journal of Baltic Studies, edited by Joan Todd, 16: 276–91.

———. 1985b. “Votive Terracotta Figures of Mothers and Children.” In Italian Iron Age Artefacts in the British Museum, edited by J. Swaddling, 195–201. Papers of the Sixth British Museum Classical Colloquium. London.

Briguet, M-F. 1988 Le sarcophage des époux de Cerveteri du Musée du Louvre. Paris. (Enlarged version, Florence, 1969)

Ehrenberg, V. 1943. The People of Aristophanes: A Sociology of Old Attic Comedy. Oxford.

Grottanelli, C. 1987. “Servio Tullio, Fortuna e l’Oriente.” Dialoghi di Archeologia, 3d ser., 5: 71–110.

Haynes, S. 1989. “Muliebris certaminis laus.” In Atti II Congresso Internazionale di Studi Etruschi 1985, 1385–1405. Rome.

Heurgon, J. 1961. “Valeurs féminines et masculines dans la civilisation étrusque.” Mélanges de I’Ecole française à Rome: Antiquité 73: 142–43.

———. 1964. The Daily Life of the Etruscans. New York.

Kaimio, J. 1975. “The Ousting of Etruscan by Latin in Etruria.” In Studies in the Romanization of Etruria. Acta Instituti Romani Finlandiae, 5: 85–245. Rome.

Kajanto, I. 1972. “Women’s Praenomina Reconsidered.” Arctos 7: 13–30.

Nielsen, M. 1989. “Women and Family in a Changing Society: A Quantitative Approach to Late Etruscan Burials.” Analecta Romana Instituti Danici 17–18: 53–98.

———. 1990. “Sacerdotesse e associazioni cultuali femminili in Etruria: testimonianze epigrafiche ed iconografiche.” Analecta Romana Instituti Danici 19–20: 45–67.

Peruzzi, E. 1970. “Il nome femminile,” Tabu onomastici,” and “La donna nella società.” In Origini di Roma, 1: 49–86. Florence.

Pfiffig, A. J. 1975. Religio Etrusca. Graz.

Rallo, A., ed. 1989. Le donne in Etruria. Studia Archeologica 52. Rome.

Torelli, M. 1975. Elogia Tarquiniensia. Florence.

Webster, T. B. L. 1972. Potter and Patron in Classical Athens. London.

Bonfante, L. 1986. Etruscan Life and Afterlife. 232–78. Detroit.

———, and G. Bonfante. 1983. The Etruscan Language: An Introduction. New York.

Brendel, O. J. 1978. Etruscan Art. Harmondsworth, Middlesex.

Haynes, S., The Augur’s Daughter (London 1987).

Macnamara, E. 1973. Everyday Life of the Etruscans. London.

———. 1990. Etruscans. British Museum Blue Books. London.

Pallottino, M. 1975. The Etruscans. Harmondsworth, Middlesex.

Sprenger, M., and G. Bartoloni. 1986. The Etruscans. New York.

Steingräber, S. 1986. Etruscan Painting. New York.