4 Disputed Salmon

OWNING AND CATCHING SALMON

‘Under Socialism: Who would get the salmon, and who would get the red-herrings?’, inquired Robert Blatchford in a best-selling tract credited with making a hundred converts to the socialist cause in 1890s Britain for every person who was persuaded by Karl Marx’s Das Kapital. More to the point, though, was Blatchford’s follow-up question: ‘Who gets the salmon and who gets the red-herrings now?’ Red herring was a very salty and strongly flavoured fish deemed an ‘indifferent kind of food’ by Charles Elme Francatelli, Queen Victoria’s former maitre d’hotel and chief cook, in his popular shilling’ cookbook for those of ‘comparatively slender means’ (1861).1 Not surprisingly, there were no salmon recipes to complement dishes such as ‘Stewed Sheep’s Trotters’, ‘Cow-heel Broth’ and ‘Baked Cod’s Head’. And the types of fish Francatelli recommended for fish pie were skate, dabs, flounders, mackerel and conger eel.

Is it not true’, Blatchford continued, ‘that the salmon and all other delicacies are monopolised by the idle, while the coarse food falls to the lot of the worker? Perhaps under Socialism the salmon might be eaten by those who catch it’.2 In his desire to make political capital, Blatchford overlooked the availability of delicious and nutritious tinned salmon from Alaska and British Columbia – a familiar sight on working-class supper plates within 20 years of Francatelli’s cookbook’s first appearance. By salmon, Blatchford meant fresh British salmon. (His reference to fishermen being deprived of the fruits of their labour also skated over the fact that the growing popularity of sports fishing meant that many of those eating salmon – however middle and upper class – were also doing the catching.) Nonetheless, Blatchford correctly identified the ownership of salmon as a time-honoured and monumental symbol of inequity.

In Scotland, all salmon fishing rights – whether in sea, estuary or river – originally belonged to the Crown. In many instances, though, the Crown had conveyed them on to individuals via written grants (King David I’s to the newly founded Priory of Urquhart on the Spey in 1124 appears to be the earliest). Ownership in England and Wales was also a royal prerogative frequently sold to favoured interests. This right was typically implemented by erecting a barrier across a river to deflect salmon into a kiddle (which later became ‘kettle’ – perhaps the origin of the expression, ‘kettle of fish’, a different or pretty kettle of fish being a kiddle damaged by weeds or raided and disabled by poachers). This arrogation of salmon was a particularly sore point in relations between nobility and monarchy during King John’s reign, demonstrating that disputes over salmon have not always aligned the haves against the have-nots. A clause in Magna Carta (1215) confronted obstacles to fish migration: ‘All kiddles for the future shall be removed altogether from Thames and Medway, and throughout all England, except upon the seashore’.3 Yet many hindrances remained in place. Richard the Lionheart eventually relinquished his prerogative to install kiddles on the Thames. Thereafter, royal decrees also specified that weirs, dams and dikes must have a gap in the middle big enough for a well-fed, year-old pig to be rotated without touching the weir with its nose or tail.

Religious folk squabbled over salmon as well as kings and barons. The Abbot of St Peter’s, Westminster, extracted a salmon tithe until at least 1382. According to the eleventh-century account of Sulcardus, this dates back to when St Peter (the patron saint of fishermen and fishmongers) came to consecrate the church of Thorney (the abbey’s forerunner). The apostle arrived on the opposite bank of the Thames one stormy night and asked a local fisherman, Edricus, to row him across and back again afterwards. In gratitude, St Peter repaid his services by a miraculous draught of salmon’, informing Edricus that he and his fellow fishermen would always enjoy an abundant supply ‘provided they made an offering of every tenth fish’ to the new church. During a bitter dispute in 1231 between themselves and the minister of Rotherhithe, Surrey, over payment of the tithe for the fish caught within the minister’s parish, the monks of Westminster successfully cited St Peter’s grant, claiming that it encompassed all salmon caught between Staines Bridge and Yenlade (Yantlet) Creek near Gravesend (effectively the Mayor of London’s jurisdiction).4

The early fourteenth century brought the first of many Scottish acts governing the use of a weir called a cruive, which, usually in an estuary, sought to catch fish heading upstream in traps set in its gaps (slaps). A meal (flour) mill serving the Burgh of Inverness in 1474 was shut by royal order because salmon were entering the lade and being killed by the wheel. Closed periods and seasons were another attempted means to secure salmon stocks. About 1220, Alexander I of Scotland enacted the ‘Saturday’s stoppe’ at Perth on the Tay, which decreed that salmon must be allowed free passage from Saturday night to Monday morning and made the taking of spawning fish or smolt a capital offence. Over the next two centuries, English and Scottish salmon streams became subject to various prohibitions on fishing between the Nativity of Our Lady (8 September) and St Martin’s Day on 12 November (extended to the Feast of St Andrew, 30 November, in 1424). Though the amount of enforcement is entirely another matter, this body of laws constitutes one of the earliest efforts to regulate the use of a natural resource.

Salmon may have been monopolized by those that Blatchford dismissed ‘as the idle’, but the privileged had to work pretty hard to protect their access to this delicacy – and sometimes from the predations of those of comparable status. Long simmering friction between the lairds of Ormidale and Glendaruel in Argyllshire boiled over on the Ruel in 1755. Ormidale, whose property was downstream from his rival’s, dammed the Ruel to drive his textile mill. Glendaruel issued an ultimatum for the dam’s removal. When Ormidale ignored his communication, Glendaruel sent a second missive protesting that the dam was interfering with salmon ascending to his estate. Failing to gain any satisfaction, Glendaruel sent his men to breach the dam, but Ormidale’s entourage promptly mended it. These actions were repeated. Glendaruel, at the end of his tether, duly informed his opponent that he planned to show up at the dam with a force of a hundred men the following morning, and invited him to turn up with an equal number. Ormidale’s forces duly appeared and faced Glendaruel’s army across the Ruel. The latter moved first, plunging into the river to destroy the dam. The warring parties met in mid-stream, brandishing their cudgels, and ‘in a twinkling a terrible struggle was in full swing’. Punches were traded, cudgel blows landed and those remaining on the banks hurled rocks. Loss of life was apparently prevented only by the timely intervention of the local minister. None, though, escaped some injury and the river allegedly ran red to the sea. The dispute was subsequently settled in court. To allow spawning salmon to reach his rival’s estate, Ormidale was ordered to erect a fish ladder (consisting of box steps) alongside his dam.5

In England and Wales, in contrast to Scotland, the public has the right to fish tidal estuaries and the sea except where the Crown or another party has specifically acquired the right. Spearing is the time-honoured method of catching salmon (legally and illegally) across the British Isles but a venerable form of inter-tidal fishing unique to the River Severn is fishing with putchers. The 1861 Report of the Royal Commission on Salmon Fisheries of England and Wales contained a detailed (if not entirely accurate) description of this ‘fixed engine’ method, modified little since Saxon times. A putcher is a trumpet-shaped wicker basket of hazel rods and willow hoops, 1.5 to 1.8 metres long, with a mouth 0.6 to 0.9 metres wide. Tapering virtually to a point at the other end to make escape impossible, a putcher resembles a giant ice cream cone. Putchers are arranged in parallel rows stacked up to four high (a rank) on the crossbars of a sturdy wooden frame sometimes 120 metres long and 4 metres high. This frame (which might consist of as many as 500 putchers) is set at a right angle to the shore, the landward end staked at the high water mark with a pole driven into a hole drilled into the flat rocky platforms of the river’s bed. (Construction of the second Severn bridge in the early 1990s disclosed traces of several of these stages, some pre-dating the Iron Age.) Many putchers face upstream to catch fish on the ebb tide; salmon swimming 60 centimetres below the surface pass over them at high tide.6

The outcome of the commission’s investigations, the salmon conservation act of 1861, barred the installation of new fixed engines and reprieved only those in place since ‘time immemorial’. Due to their antiquity, few putchers on the Severn were affected. By the 1970s, though their design remained prehistoric, on the west bank, they were increasingly made of wire and plastic and their frames from stainless steel. By century’s end, however, as salmon dwindled and anglers gained more clout, the once ubiquitous putcher fisherman had become as rare as the maker of the split cane fishing rod.7 The last putch-er rank on the Welsh bank worked at Goldcliff Point, Monmouthshire, where the Romans caught salmon to feed their garrisons at Caerleon and Caerwent. Eton College owned the fishing rights between 1451 and 1921 (though it let out the estate and received rent in kind in the form of oxen). Recently, the Wye and Usk Foundation bought out the Goldcliff fishery for five years as part of its efforts to restore these two rivers’ spawning populations.

At low tide, George Whitaker tugs a salmon from a putcher at Goldcliff Fisheries on the Welsh bank of the River Severn, 1923. |

The most ruthlessly efficient method of taking salmon, however, operated on the rivers of North America’s west coast in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: the fish wheel. This ‘infernal’ device, which resembled a fairground Ferris wheel, consisted of compartments of wire gauze that turned with the current and scooped out upstream heading salmon. During his trip up the Columbia, Rudyard Kipling saw many of these voracious contraptions in action. ‘Think of the black and bloody murder of it!’, he declared, but immediately implicated all his readers: ‘you out yonder insist on buying tinned salmon, and the canneries cannot live by letting down lines.’8

|

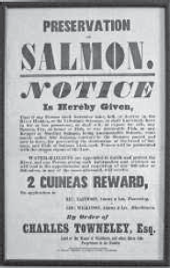

An early 19th-century warning to poachers posted by the owners of salmon fishing rights on the River Hodder in north Lancashire. |

POACHED SALMON

For those who enjoy legal ownership of the coveted salmon, the most ruthless predator, as already intimated, is often the excluded human. On the early nineteenth-century Tweed in southern Scotland, far from being a solitary and furtive act, poaching was a well-organized, largely overt activity attracting a wide cross-section of the non-gentlemanly community, from shepherds to publicans. Local police and magistrates more or less condoned a practice known as ‘burning the waters’ that was celebrated in poem, song and novel. Thomas Tod Stoddart of Kelso, one of the Tweed’s leading nineteenth-century gentleman anglers, was unwilling to condemn outright a ‘manly and vigorous’ activity with no commercial purpose that was legitimized by ‘immemorial usage’.9 His collections of angling songs and poems included ‘Sonnet – A Reminiscence of Leistering’, which was redolent with classical allusions.

A figure stood

Upon the prow with tall and threatening spear,

When suddenly in the stream he smote.

Methought of Charon and his leaky boat;

Of the torch’d Furies, and of Pluto drear,

Burning the Stygian tide for lamprey vile10

Stoddart also found room for ‘The Leisterer’s Song’, which opens and closes with these stanzas.

Flashes the blood-red gleam

Over the midnight slaughter,

Wild shadows haunt the stream,

Dark forms glance over the water.

It is the leisterer’s cry!

A salmon, ho! oho!

In scales of light the creature bright

Is glimmering below.

Rises the cheering shout,

Over the rapid slaughter;

The gleaming torches flout

The old, oak-shadow’d water.

It is the leisterer’s cry!

The salmon, ho! oho!

Calmly it lies, and gasps and dies,

Upon the moss bank low! 11

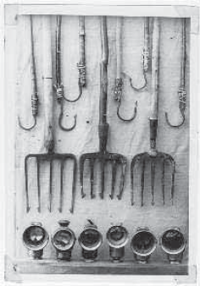

Salmon are attracted to bright objects; and a torch of burning heather or pine root held over a pool on a dark winter’s night revealed all to a considerable depth. The leister was an iron trident with five barbed prongs attached to a five-metre shaft.12 Parties usually consisted of an oarsman, leisterer and torchbearer/gaffer. By the end of the night’s exertions, their backs would be half-frozen and their fronts nearly scorched. Though some poachers wore masks of black crape, leistering was a spectator sport, with much merriment among the hangers on crowding the Tweed’s banks.13

Walter Scott, who resided on the upper Tweed at Abbotsford, and was an angler and local magistrate to boot, was particularly well qualified to report on this local custom. His historical novel, Guy Mannering (1815), contained a heavily romanticized description of the thrilling nocturnal pandemonium that burning the waters entailed.14 The voraciousness of poaching at the redds, Scott believed, could only be explained by a desire to retaliate upon those who engrossed all the fish during the open season, by destroying all such as the close-time throws within the mercy of the high country’.15 Scott proceeded to explain that landowners and the ‘better class of farmers’ regarded leistering ‘with perfect indifference’. Prosecutions were rare because ‘proof of delinquency’ was hard to secure in remote country. Officials often colluded too, with leistered salmon sometimes ended up on the dinner tables of unscrupulous water bailiffs. William Scrope, a wealthy landowner who was a friend and neighbour of Scott, related how a bailiff ‘sworn to tell of all he saw’ blindfolded his eyes before his wife served him an ‘illegal’ salmon, ‘nor was the napkin taken from his eyes till the fins and bones were removed from the room’.16

Despite the sporting fraternity’s denunciations of poaching and its demise as an organized activity in Scotland by the end of the nineteenth century, illegal fishing retained a fascination for eminent citizens. Inspired by an actual incident in 1897, John Buchan’s adventure novel, John Macnab (1925), features three middle-aged men from the upper social echelons. Sir Edward Leithen, Lord Lamancha and Mr John Palliser-Yeates are at the summit of their careers. But they feel strangely and inexplicably unfulfilled and ‘stale in mind’. ‘Try fishing’, Sir Edward’s doctor suggests, to which the former attorney general retorts: ‘I’ve killed all the salmon I mean to kill. I never want to look the ugly brutes in the face again.’ Exasperated, the doctor recommends the deliberate injection of a frisson of danger into his patient’s life. The barrister, budding cabinet minister and banker cook up a lark to restore the flavour to their lives. Signing collectively as ‘John Macnab’, they write to the owners of three Highland estates, informing them of their plans to poach a stag, a salmon and then another stag. If successful, they undertake to pay £50 to a charity of the estate owners’ choice. But if they fail, they agree to pay the proprietors £100. The estates accept the challenge. Sir Edward inevitably draws the lot for the salmon. Disguised as a tramp, the Old Etonian infiltrates his assigned estate and lands a modest eight-pounder. Next morning, a maid at Strathlarrig house discovers a wet parcel on the doorstep. (The other two Macnabs fail to avoid detection but all three are fully cured of their ennui and return to their London lives with renewed zest.)

‘Burning the waters’: L. Haghe’s colour lithograph of leistering by torchlight, the frontispiece to William Scrope’s Days and Nights of Salmon Fishing on the Tweed (1843).

In Welsh salmon country, tensions peaked on the fabled River Wye in the late 1870s and early 1880s. Armed poachers attacked water bailiffs at Crossgates and stormed the home of an official in Rhayadar. One January night in 1880, after police had failed to arrest a large gang disguised and armed with tridents, reinforcements (issued with cutlasses) were sent into Rhayadar but all they found was a salmon pinned to the door of the market hall; the attached note read: ‘Where was the river watchers when I was killed? Where were the police when I was hung there?’ On the Edw, a tributary of the Wye, as late as the 1930s, gleeful gangs with blackened faces proudly had their pictures taken with their illicit hauls to goad the local law enforcers.

These tools of the poacher’s trade – gaffs, barbed forks and lamps – were confiscated from poachers apprehended on the River Ithon in Mid Wales, c. 1910. |

In Scotland and Wales, poaching is mainly the stuff of legend. But it flourishes on the Kamchatka Peninsula, whose rivers host nearly a quarter of the world’s Pacific salmon. The Cold War, which effectively sealed off this area as a dedicated military site, keeping at bay for half a century the usual processes of economic development that bring dams, logging and oil and gas extraction, was wonderful for local salmon. Since the Soviet Union’s collapse, however, they have been targeted by poachers who supply caviar from chum roe (mainly to Japan). The local economy’s deepening dependence on ‘red gold’ as a way out of the post-Cold War slump was the subject of a TV documentary in November 2004. ‘Death Roe’ featured a paramilitary helicopter raid on a remote camp, where caviar worth $150,000 was seized from poachers who strip the roe and leave the rest of the fish to rot. (In 2004, Russia established the world’s first salmon refuge in southwest Kamchatka, which nominally protects the Kol River from source to sea.)

SALMON AND CIVIL DISOBEDIENCE

In North America, access to salmon has been far less restricted than in Britain. Yet resentments against elites rankled here too. Leistering by torchlight, for example, was also popular among mid-nineteenth-century settlers in Lower Canada (Quebec). President Theodore Roosevelt’s uncle, one of the growing clique of wealthy American sportsmen who relished salmon fishing in Quebec in the 1860s, believed that leistering ought to have been punishable by death or, at least, life imprisonment.17 The Pacific coast, though, is where the sparks really flew. If the entrenched interest in Britain was the Crown – entrenched, that is, in the sense of original ownership – here it was the native peoples. According to the Treaty of Neah Bay (1855), in exchange for relinquishing large areas of land, the Makah were guaranteed ‘the right of taking fish at all usual and accustomed grounds and stations in common with the citizens of the territory’. This was not so much a grant of rights as the guarantee of rights already possessed. And, at the time, this was not contentious as Euro-American settlers were primarily interested in terrestrial resources. But this changed once the canning industry got into full swing.

Flexing its muscles as a new state in the 1890s, Washington banned various customary means of Indian fishing (snagging, spearing, gaffing and snaring). Indian fishing was further restricted in the name of conservation; their catch might be small in comparison with commercial and sport fishermen’s takings, but Indians allegedly hit salmon disproportionately hard by taking spawning stock. Indians could thus be targeted without inconveniencing commercial outfits that harvested salmon before they entered rivers.18 Blaming Indians fishing with traps in rivers for falling stocks was more palatable politically than tackling the commercial purse seiners and trollers who fished in the sea beyond state jurisdiction, the logging companies that often blocked rivers with the logs they floated downstream or the effluent-discharging pulp and paper mills.

Matters came to a head in the turbulent 1960s, when the ‘red power’ protest movement added fish-ins to the decade’s better known sit-ins, love-ins and be-ins. As salmon runs faded, the state of Washington’s fish and game agents used guns, clubs, dogs and tear gas to break up Indian fishing that violated state law. Jane and Peter Fonda, two actors associated with radical causes, joined the fish-ins. But the best known supporter was Marlon Brando, who stood shoulder-to-shoulder with native fishermen on the waterfront. In March 1964, at the mouth of the Puyallup River in Tacoma, Washington, a traditional site closed to Indians since 1907, Brando and the Puyallup tribal leader, Bob Satiacum, were arrested for catching salmon with a driftnet in defiance of state law.

As tensions peaked in the autumn of 1970, the federal government finally intervened. After three years of fact-finding, testimony and deliberation, the senior US district court judge delivered his 203-page decision in February 1974. A sport fisherman with a solid conservative reputation, the elderly George Boldt shocked local white interests (as well as Indians) by not only sustaining treaty rights but defining ‘fair and equitable share’. Boldt ruled that Indians should have the opportunity to take up to half of the harvestable catch at their usual and accustomed places, non-treaty fishermen enjoying the same opportunity (using Webster’s dictionary of American English, 1828 edition, he ruled that the phrase ‘in common with’ meant ‘divided equally with’). This landmark ruling was informed by the ascendant notion of the Indian as proto-ecologist. ‘Religious attitudes and rites’, Boldt explained, ‘insured that salmon were never wantonly wasted and that water pollution was not permitted during the salmon season.’19 Outraged white commercial and sports fishermen burnt Boldt in effigy and a witty new bumper sticker appeared: ‘Can Judge Boldt’.

Boldt realized that fishing at sea by non-Indians prevented many salmon from reaching those usual and accustomed places (the Indian proportion of the Columbia’s catch in the early 1970s was only 5 per cent).20 Accordingly, he ordered state fish and game authorities to manage salmon populations so that Indians could catch half of the runs that they historically fished.21 Now that the Indian right to harvest half the available salmon has at last been generally accepted and is finally being enforced, not many salmon, unfortunately, are left for them to harvest.

The Indian fisherman doubtless derives as much pleasure from pursuing his salmon as any white angler. The next chapter takes a closer look, though, at the group with which these joys and thrills are most commonly associated: the sportsman (and sportswoman) for whom the quest for salmon was the most sublime of recreational pursuits.