5 Sporting Salmon

THE SEDUCTIVE SALMON

‘I have lived!’ exclaimed Rudyard Kipling; ‘The American Continent may now sink under the sea, for I have taken the best that it yields, and the best was neither dollars, love, nor real estate.’ The best that America had to offer was salmon. The day after he observed the Columbia’s frenetic canning operations in 1889, Kipling was taken salmon fishing on the Clackamas. Having tasted glory by landing a 5.5 kilogram salmon on a fly after a 37-minute tussle, he made this ecstatic pronouncement (despite his lacerated fingers).1

Kipling was not alone in picturing paradise with a salmon river running through it. The ranks of the equally besotted fly fishers include American presidents and British prime ministers, British royalty and American movie stars, industrialists, novelists and celebrities. And not all are male.2

Some authorities trace the origins of fly fishing to the River Astraeus in third-century Macedonia (where trout was the quarry). The first rods, made of hazel shoots, were relatively short at about two metres. The fixed lines, roughly the same length, were fashioned from knotted horsehair. This method spread across Europe and vied with the spear as the preferred implement of the common folk for catching pike and carp as well as salmon and trout.3 The longer rod (often jointed and perhaps extending to just over four metres) and line (though still fixed and hand-made from horsehair) appeared in late medieval times. This was probably the kind used by the author of what is generally considered to be the first celebration in English of fishing for salmon with rod, line and feathered hook: A Treatyse of Fysshynge wyth an Angle (published in 1496 as part of the second edition of The Boke of St Albans). The author’s identity has never been established definitively, but the most popular choice is Dame Juliana Berners (Barnes), prioress of the Benedictine nunnery of Sopwell, near St Albans. Hailing the ‘samon’ as a ‘more statelye fysshe that any man maye angle to in fresshe water’, she proceeded to give detailed instructions for catching one (no mean feat given the rudimentary state of the available equipment): ‘The Samon is a gentyll fysshe, but he is cumberous for to take. For commo[n]ly he is but in depe places of great ryuers, and for the moste part he holdeth him in the myddes of it, that a man may not come at hym’.4

|

The Marquise de los Agnes Valentia (Viscount Annesley) and his party display their catch from the River Wye in Builth Wells, Powys, in the summer of 1925. |

Major pre-industrial advances in fishing technology appeared in the mid-seventeenth century – the era of Izaak Walton (1593–1683).5 While some lines remained fixed, others were threaded through loops screwed into the tip of a rod. The end of the line was hand-held or, increasingly, wound around a reel clipped to the butt of the rod (usually made of bamboo cane). This permitted a superior and longer cast. Flies were also becoming more sophisticated, varied and colourful (and exotic in terms of the raw materials from which they were assembled – not least a staggering range of feathers from macaw to peacock). Running rings supplemented the tip ring on rods by the late 1600s (though they often popped off when the angler was playing a fish). Jointed rods with top sections of bamboo were generally available by the mid-eighteenth century. Industrialization brought ready-made flies, manufactured lines and tackle dealers to sell them.6

Selection of hand-tied Atlantic salmon flies (mostly hairwing type, including cossebooms, an undertaker, a copper killer, and a green machine). |

|

L. Haghe’s watercolour Ascertaining the Weight, shows retainers weighing up a gentleman’s catch; from William Scrope, Days and Nights of Salmon Fishing on the Tweed (1843).

Fly fishing by non-residents really took off on British rivers in the 1840s and 1850s, thanks to royal example and facilitated by the expanding railway network. Prince Albert and Queen Victoria started spending their summer holidays salmon fishing in the Scottish Highlands in the early 1840s and the landed aristocracy who followed their lead were, in turn, emulated by the new moneyed class of industrialists and financiers who adopted this leisure pursuit as part of their quest for social respectability. The most accessible Scottish river, the Tweed, was a particularly popular destination. By the 1850s, the locals who fished for a living or to supplement their protein supply could no longer afford the rents that English gentry and industrialists were prepared to pay.7 The visiting angler typically came armed with a five-metre jointed rod of ash, hickory, bamboo or greenheart with a whalebone tip and brass joints, a reel (American makes were the most swish) and a line more likely to have been braided silk than horsehair. (Fibre-glass rods, nylon line and rubber waders were still a long way off.)

These Victorian Britons were convinced that their relationship with the sport was special. ‘A plant – as it were – of pure English growth.’ This is how a guide to salmon fishing in Norway (1848) hailed the sportsman, who supplied further proof of British superiority over their French neighbours. For who ever heard of a Frenchman travelling some twelve or fifteen hundred miles for the avowed purpose of catching Salmon?’8 British anglers felt just as strongly that the salmon was peculiarly British in its rugged resolution and refusal to say die: ‘he will charge the fierce and boiling stream, he will rush at a cataract like a thorough-bred steeple-chase horse, returning to the charge over and over again, like a true British fish as he is’.9

The Victorian salmon angler’s world was unashamedly exclusive as well as chauvinistic. He oozed distain for the tourist angler as well as the French – the ‘Arrys’ who ‘leave unpleasant souvenirs of their visits in the shape of lunch papers and perhaps small heaps of broken bottles for good dogs to gallop over!’10 The monarch of the glen – as Sir Edwin Landseer dubbed the stag in his iconic painting (1851) for the labels of John Dewar’s whisky – thus had its aquatic counterpart in the ‘monarch of the loch’ and the ‘monarch of our rivers’.11 The king of fish was also the king’s fish. Balmoral in Aberdeenshire, the royal family’s Scottish seat that Albert acquired for Victoria in 1852, includes 24 kilometres of prime fishing on the Dee’s south bank. Victoria, Edward VII and George V were all keen salmon anglers. So is Prince Charles (‘You may not have fished yourself, to do so for salmon is immensely exciting’, he wrote from Balmoral to the tinned salmon-preferring Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, in September 1969.)12 The most famous royal fisher, though, was Elizabeth the Queen Mother (1900–2001). Fly fishing for salmon was her favourite pastime.

Entries by the Duke of Beaufort and others from the visitor’s book at the Severn Arms Hotel, Penybont, Powys, Spring 1881. |

Nineteenth-century paeans abound. The Scottish poem, ‘The Taking of the Salmon’, well-known on the Tweed, opens with these two stanzas:

A birr! A whirr! – a salmon’s on,

A goodly fish! a thumper!

Bring up, bring up, the ready gaff,

And if we land him, we shall quaff

Another glorious bumper!

Hark! ‘tis the music of the reel,

The strong, the quick, the steady;

The line darts from the active wheel,

Have all things right and ready.

and closes with these two:

No birr! No whir! The salmon’s ours,

The noble fish – the thumper;

Strike through his gill the ready gaff,

And bending homewards, we shall

quaff Another glorious bumper!

Hark! To the music of the reel

We listen with devotion,

There’s something in that circling wheel

That wakes the heart’s emotion.13

One of those whose emotions fly fishing never failed to awaken was Sir Humphry Davy (1778–1829). The English chemist who discovered the anaesthetic qualities of nitrous oxide (laughing gas) is best known as the inventor of the miner’s safety lamp. Yet he was also an inveterate angler. Writing a book about his consummate passion supplied a welcome diversion from pain and misery at a time when he was seriously ill and wholly incapable of attending to more useful studies’.14 Salmonia; or Days of Fly Fishing mimicked the format and conversational tone of Walton’s Compleat Angler (though his friend, Walter Scott, regarded it as more factually reliable and informed by broader experience). An ‘accomplished’ fly fisherman (Halieus) replies to and refutes a friend’s objections to angling – not least its cruelty (arguing that the nervous systems of cold-blooded creatures are less sensitive than those of mammals). Then, having converted him, Halieus instructs in the art. Walton, in Scott’s view, lacked vision and a sense of adventure, Compleat Angler giving the impression of ‘a most cockney-like character, and we no more expect Piscator to soar beyond it, and to kill, for example, a salmon of twenty pounds weight with a single hair, than we would look to see his brother linen-draper, John Gilpin, leading a charge of hussars’. In fact, Scott doubted that Walton had ever seen a live salmon.15 Whereas Walton had not ventured far beyond London, Davy struck as far north as the hallowed Tweed, where he reputedly landed a 19-kilogram salmon above Yair Bridge.

For Scott, nothing came close to this particular sport:

It requires a dexterous hand and an acute eye to raise and strike [the king of the fish], and when this is achieved the sport is only begun, at the point where, even in trout angling, unless in case of an unusually lively and strong fish, it is at once commenced and ended. Indeed, the most sprightly trout that ever was hooked shows mere child’s play in comparison to a fresh-run salmon . . . The pleasure and the suspense are of twenty times the duration – the address and strength required infinitely greater – the prize, when attained, not only more honourable, but more valuable.16

Salmon priest: the lead-headed cosh is so named because it was used to deliver the last rites to a fish that had been landed.

Alexander Russel, editor of The Scotsman, Scotland’s leading newspaper, acknowledged the ostensible foolishness of the exercise in his effort to explain its appeal in the 1860s. ‘Look at that otherwise sensible and respectable person, standing midway in the gelid Tweed . . . his shoulders aching, his teeth chittering, his coat-tails afloat, his basket empty. A few hours ago probably, he left a comfortable home, pressing business, waiting clients, and a dinner engagement.’ Why? Because, Russel continued, men ‘not ignorant of any of the delights to which flesh has served itself heir’ were convinced that ‘the thrill of joy, fear, and surprise . . . induced by the first tug of a salmon, is the most exquisite sensation of which this mortal frame is susceptible’.17

Given the intensity of these feelings, the urge to transplant these pleasures to Australia and New Zealand was irresistible. A newspaper in Melbourne, The Age (2 April 1858), placed the salmon at the centre of a grand acclimatization plan to render the province of Victoria more familiar to British settlers, hoping ‘to see the horse-chestnut and the oak add grandeur and variety to our woods . . . to hear the nightingale singing in our moonlight as in that of Devonshire, to behold the salmon leaping in our streams as in those of Connemara or Athol’.18 Sir James Arndell Youl, a prominent Tasmanian colonist, devised the method for successful transmission of ova; by placing the eggs on charcoal and living moss in perforated wooden boxes under ice, they could be kept alive for a hundred days. The clipper Norfolk left London in January 1864 with 18,000 salmon ova. The first successful shipment from Britain took place later that year (100,000 salmon ova that Buckland collected from the wild). California rivers were also a source of transplants. But the first shipment from the Country Club of San Francisco to Melbourne, Victoria, also in 1874, was a fiasco. The packing ice melted en route, the eggs hatched and the fish died in a ‘putrid mass’.19

THE NORWEGIAN ATTRACTION

Davy’s ‘Halieus’ had fished in Norway and Sweden but Scottish streams were good enough for him.20 By the 1830s, though, an English angler explained, salmon fishing had become such a popular sport that ‘the ancient haunts within the British dominions no longer suffice’. And even a piscatorial patriot like Halieus had noted that renowned Scottish rivers were not what they used to be. The intrepid angler’s new frontier was Scandinavia, which produced few of its own anglers. The pioneers were Lewis Lloyd and William Bilton (a.k.a. Belton). Captain Lloyd, who his editor hailed as ‘a fine specimen of the English gentleman’, spent two years roaming Scandinavia in the 1820s. He thrilled to the prowess of Norwegian spawning males, who apparently charged one another with such force that the weaker adversary was sometimes tossed out of the water. Some of the fish to be caught in Norwegian rivers, he insisted, were the size of porpoises.21 Two Summers in Norway, Bilton’s account of his exploits in 1837 and 1839, was the first to popularize Norway’s premier salmon river, the Namsen. Despite the rigours of the journey and the ‘unaccustomed frugality of Norwegian fare, and the want of usual comforts’, Bilton (a reverend) maintained it was well worth the effort.22 A clutch of guides followed the first, and most widely read, Jones’s Guide to Norway, and Salmon Fisher’s Pocket Companion (1848). Written for the ‘wandering Walton in a Foreign Land’, it hailed Norway as an ‘unrivalled’ ‘fluvial paradise’.23

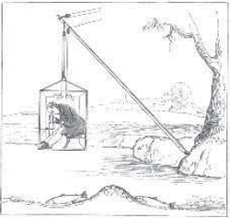

Alexander Keiller’s moveable observatory at Jonserud on the River Save, a tributary of the Swedish Gotha; from a drawing by Keiller. |

|

These guides were highly effective publicizing tools, but the likes of the Dukes of Marlborough, Roxburgh and Westminster did not want to rough it in the style of Lewis. So they built sumptuously outfitted and provisioned lodges. Colonel Frank Dugdale of Wroxall Abbey (Warwickshire), who fished on the Namsen at Moum between the early 1880s and 1900s, had one of the most substantial and attractive of these lodges built in an English style in 1891. The golden age of the so-called ‘lords’ rivers’ ended with World War I. After 1919, most aristocrats were too impoverished and/or heavily taxed to afford these excursions. Industrialists (especially munitions manufacturers) and bankers who had superseded them in wealth sometimes took over their leases. Reports that mixed nostalgia with grumbling were a frequent feature of post-war angling magazines. One disgruntled author, who first fished Norwegian rivers in 1870, complained that rents were now at ‘Scotch level’ and the fishing mostly ‘indifferent’.24

John Singer Sargent, On His Holidays, painted in 1901. Alexander, the 14-year old son of Singer’s American patron George McCulloch, relaxes after sal on fishing in Norway.

While British anglers were discovering Norwegian rivers, Canada’s had also started to teem with fly fishermen. Salmon angling was the chief recreational pursuit for British colonial officials and military officers in eastern Canada. They were soon joined by American industrialists who formed the backbone of prestigious clubs that sprouted up on the region’s rivers and secured exclusive fishing rights. The oldest and most exclusive, the Restigouche Salmon Club, was founded in Matapedia by nine Americans in 1880. These clubs were sufficiently affluent to snap up riverfront acreage adjacent to the best pools and to pay farmers not to fish in streams that ran through their farms. They also hired their own wardens. Nonetheless, organized poaching was a huge problem on some Canadian rivers and government officials struggled to maintain order. As in mid Wales, the homes and barns of wardens were burnt down in the 1890s. One particularly ugly confrontation in 1888 between leisterers and out-of-town anglers culminated in the death of an American sport fisher. In many rural areas where arable farming yielded a poor return – as in Scotland – convictions were hard to secure as magistrates often sided with their friends and neighbours against outsiders who were usurping their basic entitlement to take salmon for their immediate needs. In the case of the dead American, the jury returned a verdict of manslaughter.25

THE POLITICIAN’S RELEASE

One of the most obscure late nineteenth-century American presidents, Chester Arthur, held the record (23 kg) for a salmon caught on a fly along a stretch of Quebec’s Cascapedia River. So many presidents have been so enamoured of angling that Bill Maree has been able to write a 270-page book on the subject. As Maree explains, angling (for fish ranging from ‘lordly salmon to the lowly perch’) was a peerless way of escaping the pressures of the job.26 Harry Truman, Dwight Eisenhower, Jimmy Carter and George Bush, Sr were passionate salmon anglers. So was Calvin Coolidge – a decidedly cold fish in most other respects. Yet the most famous salmon fisherman to occupy the White House was Coolidge’s successor in the late 1920s, Herbert Hoover. As Secretary of Commerce in the two previous Republican administrations, he worked hard to protect Alaska’s salmon stocks from overfishing. He also served as honorary president of the newly formed Izaak Walton League of America (1922), an angler’s organization that campaigned for the conservation of fish habitat. For Hoover, angling was anything but exclusive. On the contrary, the inalienable right of all Americans to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness included – self-evidently, in his view – the pursuit of fish.27 Angling was also a supremely democratic pursuit because, before the fish, all anglers stood equal. And, no less importantly, there was nothing more ennobling than fishing.

Hoover was accustomed to receiving gifts of salmon. During his tenure at Commerce, canners regularly sent him fresh specimens from Alaska. But his favourite offering came from the Penobscot Salmon Club of Bangor, Maine, the nation’s first salmon fishing club. Since 1912, the club’s directors had traditionally delivered to the White House the first spring salmon that a club member caught in the Bangor Salmon Pool.28 The photographs taken on the White House lawns to mark these solemn occasions adorned the walls of the club headquarters, high above the Penobscot River overlooking the aforementioned Pool. There was a major hitch in the normally smooth running of this annual ritual during Hoover’s first year in office (1929). As Hoover explained, a ‘new and uninformed’ White House official sent the fish straight to the kitchen, where the cook immediately prepared it for the oven. In a bid to rescue the day, the cook sewed the head and tail back on and stuffed the fish with cotton. Still, there was something fishy about the photographs if you looked closely.29 In the late 1930s, this bipartisan tradition broke down, if temporarily, under the pressure of intense political polarization. In 1938, Penobscot club member Sylvia Ross, a Republican stalwart hostile to the New Deal and its chief architect, was so upset at the prospect of the first salmon landing on Franklin D. Roosevelt’s dinner table that she paid top dollar to ensure that it did not reach the White House that year.30

President Herbert Hoover is presented with his gift of the first salmon of the 1931 season caught in Bangor Pool on the Penobscot River, Maine. |

THE FEMALE TOUCH: WOMEN IN RUBBER31

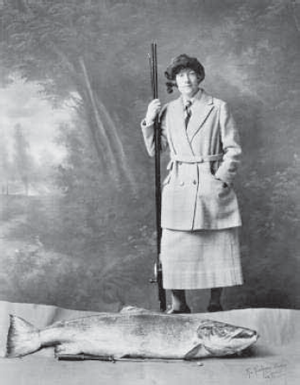

We have, indeed, often thought’, reflected Walter Scott in his review of Davy’s Salmonia, ‘that angling alone offers to man the degree of half-business, half-idleness, which the fair sex find in their needle-work or knitting, which, employing the hands, leaves the mind at liberty, and occupying the attention so far as is necessary to remove the painful sense of a vacuity, yet yields room for contemplation, whether upon things heavenly or earthly, cheerful or melancholy.’32 Yet women anglers were not unheard of in Victorian times, for, as another authority pointed out in 1871, ‘sex forms no barrier’.33 And in the early twentieth century, a woman who had traded her knitting needles for a rod and hook showered herself with glory. One of the most celebrated beats on the Tay is Glen Delvine. Here, on 7 October 1922, Miss Georgina Ballantine (using a spinner and rod from P. D. Malloch’s store) landed what remains the UK’s record for a rod-caught salmon (also the largest fish ever landed in British freshwater). The fish weighed over 29 kilograms and measured 1.37 metres; its girth was 72 centimetres, its head 30 centimetres long and its tail just under that at 28 centimetres.34 The cast is on display in Perth’s museum and art gallery. Underneath is Miss Ballantine’s own, understated account of her feat. She was not a member of the original fishing party that Saturday, joining only after someone dropped out. She had already caught three salmon of a respectable size (11, 9.5 and 7.7 kg) from the boat that her father was rowing when the light started to fade. At 6.15 p.m., as the sun was descending behind Birnham Hill, she made one last cast. What was clearly a very powerful fish seized her bait. After a contest that lasted two hours and five minutes – and left her with a cut forefinger as she tried to check the line – she landed the whopper half a mile downstream in pitch blackness. A reading of his scales indicated that he had spent two years in freshwater and three years at sea before returning to the Tay. After posing for pictures with her fish, and once Malloch had made a cast, she donated it to the Perth Royal Infirmary, where it was ‘relished by both patients and staff’.35

Miss Georgina Ballantine’s record salmon from the River Tay, 1922. |

In fact, women hold all the British records for rod-caught salmon.36 In the late 1930s, a male angler ventured an explanation. Women were far more patient and sometimes bested men in strength and stamina (many male anglers had refused to accept that Miss Ballantine’s father, despite his protestations, had not assisted her). Ultimately, though, the explanation was self-evident, consonant with a well-worn gender stereotype: ‘women may be presumed to be specially fitted to practice successfully all the arts and artifices necessary to lure, cajole, entice, cozen little and big fish to her hook’.37

The opportunities for women to demonstrate their so-called feminine wiles are shrinking, though. The White House received its last Penobscot salmon in 1994 and less than a thousand currently return to that river, compared to 70,000 two centuries ago. Yet the Penobscot is considered the last best chance for restoring a healthy run of Salmo salar to an American river. An encouraging sign, in 2003, was an agreement to remove a string of hydro-electric dams.

THE SALMON’S BEST FRIEND

Major Kenneth Dawson of Devon dedicated his 1928 book on local salmon and trout to the fish ‘which has given me many of the best days . . . of my life’.38 In return, anglers have tried to give the salmon something back: respect and a healthy future. Angling in Scotland remains steeped in ritual. At the village of Kenmore, where the Tay flows out of Loch Tay, a ceremony marks the first day of the season in January. A parade, led by a pipe band and celebrity anglers such as the broadcaster Fiona Armstrong, heads from the Kenmore Hotel to the river. When they get there, the salmon and the river are toasted by pouring a quaich of whisky over a boat. The season’s end is also marked ceremonially.39

Securing the Atlantic salmon’s future requires more than respectful ritual, however. Buying out the last drift netting operations may be the best bet for saving and restoring the salmon. Drift nets, which extend miles, are invisible and have tiny mesh. Salmon returning to their natal streams stand little chance of avoiding them. In 2003, the Atlantic Salmon Fund, an international organization founded by Orri Vigfusson, an Icelandic vodka magnate, bought out the last remaining drift netting operations in northeast England to revive the Dee’s and the Tweed’s stocks. Vigfusson’s goal is to restore salmon populations in great European rivers such as the Loire and Rhine to what they were two centuries ago.

Casting a fly on the River Wye, early 21st century.

In economic terms, a salmon caught by a sportsman (who often releases it unharmed) is worth umpteen times more than one caught in a drift net. In the meantime, though, the sport fishing business in regions such as Scotland’s west coast is virtually dead. Loch Maree, Wester Ross, was such a fabled destination for salmon (and sea trout) anglers that Davy’s alter ego, Halieus, gives a enraptured account of landing a hallowed fish in the River Ewe that connects the loch to the sea.40 Half a century later, the fishing was still so good that Queen Victoria spent a week of September 1877 at the Loch Maree Hotel. Now, there are more salmon on the walls in the Gillies Bar than in the water. In Connemara, Ireland, Ballynahinch Castle Hotel has also been badly hit. Local wild salmon (and sea trout) populations have disintegrated, due partly to lice infection from nearby farms (though drift netting doubtless aggravates the predicament). The salmon’s monetary value to a local economy is one thing. Its larger value is something else. Taking one of the noblest of creatures and converting it into livestock, claimed Patrick O’Flaherty, the hotel’s general manager in 2003, ‘goes against everything that is natural’.41 This begs a bigger question, not just for salmon history but for our relations with the rest of nature as a whole: what exactly does it mean to be natural? I shall revisit this question in the conclusion, after considering another aspect of the salmon’s value: its cultural currency – expressed in ceremony, myth, visual art, modern western literature and sculpture – for the peoples who co-inhabit its world.