19 ~ Marion Richardson

If this book has a hero, it’s the proponent of child-centred art and writing, Marion Richardson. She was primarily a teacher of art, and fascinated by children’s art years before the avant garde turned it into a cult object. She must have been a woman of extraordinary energy and originality of mind. Born in 1892, she brought Roger Fry a portfolio of work executed by her pupils at Dudley Girls’ High School in 1917. It was a remarkable collection. Only in her mid-twenties, she had removed her pupils from any notion of copying and rote imitation, going as far as to ask ‘her pupils to sit with closed eyes, perhaps listening to a description, and [waiting] for images to appear in “the mind’s eye”.’1

Across the world, traditional methods of teaching and perception were up for grabs. It’s interesting to speculate what Richardson would have made of Paul Klee’s teaching methods, just then about to be launched on an unsuspecting Bauhaus in Weimar. Klee’s teaching was based, in a revolutionary way, on theories of colour, patterning and many other abstract designs in ways that refer back to the pleasure of the moving body and idiosyncratic ideas of movement and form. In the same way, Richardson regarded movements not as things to be subdued and made to conform, but things to master and control for expressive purposes. I have a copy of the Teacher’s Book which went with Richardson’s unassumingly titled Writing and Writing Patterns, published in 1935, and it’s an object of strangely alluring physical beauty. It’s just the size of a floppy school exercise book, covered all over with five-pointed stars, a pleasure to handle and full of unexpected delights. A book full of a kind of spiritual beauty, too: Richardson’s love of children in all their weird variety and inventiveness, and her love of the presence and energy of simple shapes on paper just shine out of her work. She was a solid, plain-looking, intelligent woman: Klee would have loved her.

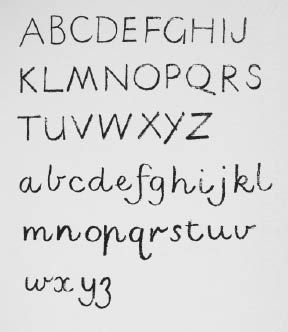

The Marion Richardson alphabet.

Richardson’s programme aims towards a free cursive handwriting, and she says, as A.N. Palmer was saying shortly before her, that it should use ‘only easy movements of the hand and arm’.2 Richardson’s wonderful insight was that these easy movements were to be found in children before they even thought of writing, ‘in primitive forms of decoration and in childish scribble’. Unlike Palmer, whose classes centred on the blackboard, and on grim unison drills, Richardson wanted the child to explore a range of patterns for themselves, playing with crayon on paper as a foundation of good handwriting. She warns against imposing an ‘adult sense of correctness’ on children. After reading of handwriting masters whose interest is in conformity, duty, and preparing for a job in commerce or the civil service, it is a pleasure to come across someone who really knows what it is to be a child, and sees that not as something to subdue in the interests of a professional future in an office, but something valuable in itself.

These pre-writing exercises are of very great importance. Not only are they a source of delight to the little child, being but a development of the spontaneous scribble that children make in imitation of ‘real’ writing, but by presenting the several writing rhythms in isolation one at a time, they make it possible for him to experience the essentially cursive nature of handwriting from the beginning, even before he has actually learnt to write.’3

For the first time ever, perhaps, a reforming figure has not only noticed that the child can have pleasure and even ‘delight’ in making marks on paper, but has made that absolutely central to the programme. I had to sneak off to make looping cursives that resembled handwriting before I could actually write anything in it. If Marion Richardson had been anywhere in the vicinity, I would have been actively encouraged to do it in the classroom as an important stage in learning to write.

Richardson sets out a series of patterns to inspire the child – she’s very clear that they should be allowed to invent their own patterns rather than slavishly copy these. They are a line of zigzags, a looped pattern ‘which is a great favourite with children … and goes well to the jingle “up curl, down curl”’, broken patterns, and still more. ‘A rich and almost endless variety of patterns will appear if the children’s powers of invention and visualization are encouraged, and if they are allowed to colour the shapes of their patterns after they have outlined them.’

You could have a small pause at this point to imagine what would happen if anyone suggested to A.N. Palmer, Vere Foster, Spencer or even Edward Johnston that students be ‘allowed to colour the shapes’ in handwriting practice. Even when we get to children up to the age of nine, when Palmer was no doubt starting to think they ought be sending their CVs out to the blacking warehouse, Richardson is still thinking of ways to make writing fun in this way – ‘it will of course add to the children’s pleasure in writing these copies if they use coloured ink as well as black’. Utterly true: it was a delight at Christmas to get a small box of Winsor & Newton coloured inks, with those interesting pictures on the side – canaries to indicate the yellow, and so on – and then to spend the patch between Christmas and New Year writing thank-you letters to all the rellies in one lurid shade after another.*

Trembling, not quite expressed, in Richardson’s argument is a sense that every stage in the learning of handwriting has its own value and beauty; they shouldn’t be rushed through in order to attain the perfect adult handwriting. And this is true. We certainly recognize, without any hesitation, the difference between a neat child’s handwriting and an adult’s. A mixture of cultural development and of educational accomplishment means that we can probably tell the difference in most cases between the hand of someone of twelve, twenty, forty and eighty. But should any of them be automatically regarded as inferior to any other? Aren’t the delighted discoveries of a new writer of seven as rewarding and satisfying as an old writer of thirty? These questions hover over Richardson; none of her predecessors would have found them the slightest bit comprehensible.

There are two photographs of classes at work that show the immense shift between the pseudo-militaristic approach which culminated in Palmer and Richardson’s ideas of starting with what the child can do, and what he will enjoy doing. If you look at one of Palmer’s classes the desks are arranged in rows; the students sit facing the same direction; their pens are poised at exactly the same angle, as, indeed, are their heads. Their own mothers couldn’t tell them, or their work, apart. And on the wall – it is quite hard to see, but it looks rather as if what hangs on the wall are photographs of Great Presidents of the USA, or possibly even Mr Palmer’s own face. In the photo of Richardson’s class, her pupils are standing up at easels – it was clever and observant of Richardson to know that very young children find it easier to wriggle than to sit still, and prefer to work where they can move about freely. Sitting still is a perfect torture to many small children, and it is much nicer to stand up. These ones are dressed in sensible, loose clothes that can bear an ink stain or two. They are making different patterns on their sheets of paper, and have reached different places. Their work is not lined up in rows, but positioned wherever they happen to be, and, working on either side of an easel, two children can happily talk to each other as they concentrate on their work. Best of all, on the walls, properly framed, are examples of the nicest of the children’s work, coloured in and there for everyone to enjoy. In other photographs, if children have to sit at a table, they face each other as they work, not the authority at the front; in another, they lie prone, the paper on the floor; in another, they have been encouraged to build pretend shops in the classroom. It must have been fantastic fun to have had Miss Richardson teaching you. She says, in her book, that ‘the [photographs of] classroom scenes are given as being the next best thing to seeing the children themselves at work’.

Richardson was an art teacher before she interested herself in handwriting teaching,* and her joy in pattern-making in small children is like a Mameluke master of decorative geometry, saying approvingly, ‘The movement is very light and swift’, ‘the added rings complete the pattern very successfully’, ‘the movement is swift and beautifully controlled’, ‘an ingenious variation’, ‘the contrast between the large pattern … and the small pattern made from ea is very happy’, ‘a fine swinging movement makes an interesting shape’.4 And they are beautiful; they look very much like the patterns that Paul Klee was introducing into his own painting at around the same time, and was to go on to encourage in Bauhaus students.

An exercise from a Marion Richardson textbook. The patterns on the left-hand page are meant to aid with the letters on the right.

The letterforms that Richardson encouraged students to work towards have a slightly italic quality to them – they are upright, and the students’ books progress towards the use of a broad-edged nib. But her style is generous and broad, and throughout stresses what is easy to write, and a pleasure, and what is easy to read. Unlike the masters of italic, Richardson felt that the number of lifts of the pen should be limited in the interests of speed and ease – some italic teachers have no particular objection to repeated lifts in the course of a word, and even in the middle of letters. As a model of teaching and learning, enabling the child to progress at his or her own pace, with pleasure at their own achievements at every stage, it could hardly be improved on. The basic style of Richardson’s letters were nearly ideal: stripped of obfuscating ornament, but still able to move at a smooth cursive pace. There are no loops in Richardson, though I know plenty of people who have chosen to introduce them subsequently, in the interests of ornament.* As I said earlier, though I admire Richardson’s style immensely, I did feel, at ten years old, that there must be more to life than her distinctly no-nonsense f’s.

By the 1930s, the principal schools of handwriting were established, and by the 1950s, the different schools were fighting for dominance. The old-style copperplate had its refined proponents; the Civil Service/Palmer hand was still claiming efficiency in the business world; educationalists were fighting over the different principles represented by print hands – even the fundamentalists who insisted that cursive should never become necessary – and Marion Richardson’s running cursive, child-centred at every stage; and somewhere, the italic obsessives were forming societies and pressure groups and writing each other letters beginning ‘I wonder if I might momentarily crave your distinguished attention.’