20 ~ Reading Your Mind

Like most people, I have a set of unexamined prejudices about handwriting. It’s not so much a set of prejudices about the look or style of writing. It’s more about the ways in which characters reveal themselves through handwriting. Probably we all believe that we have some sense of what people are like through the way they write. That is one of the reasons why it was so disconcerting to realize that I didn’t know what the handwriting of a good friend of mine looked like. Because of the way we live and write now, I had been deprived of a crucial piece of evidence in the art of reading, interpreting, discovering the personalities of my friend. For all I knew, his handwriting slanted backwards at forty degrees.

We needn’t make a systematic study of character through handwriting to realize we have some firm principles. We’ve seen that Dickens already in the nineteenth century had views about what constituted a woman’s handwriting, a villain’s, perhaps (in Little Em’ly’s too-large and too-black handwriting) that of a woman with too-strong sexual desires. I don’t suppose he had thought about these matters precisely; all the same, he had made his mind up.

Here are some of the things which I believe can be inferred about a person from their handwriting. If I had a letter from a stranger, I would have a sense of what they were like almost before I started reading.

1. People who don’t join up their letters are often creative, and often visually imaginative. Alternatively, they may be a little bit slow.

2. People whose handwriting leans forward are often conventional in outlook; people whose handwriting leans backward are often withdrawn.

3. People who don’t close up their lower-case g’s are very bad at keeping secrets.*

4. People whose writing doesn’t have much in the way of ascenders or descenders – stubby f’s and y’s which just gesture downwards deadly – don’t have much of a sex life.

5. If someone’s handwriting leans to left and right and upright like a drunk sailor in a gale, and sometimes joins up and sometimes doesn’t, then they might one day murder someone for no reason at all.†

6. People whose handwriting is mainly round are generally nice. Generally, I said; generally.

7. Someone who uses the Greek E probably had an early homosexual experience.

8. People whose signature is wildly different from their normal writing may or may not be trustworthy, but they aren’t altogether satisfied with their existence.

9. People who underline their signature are convinced of their own significance in the world.

10. If you ever come across anyone who signs their name and then, instead of underlining it, runs a line through it, run a mile. Years of therapy await.

11. Anyone who writes a circle or a heart over their i’s is a moron.

12. A handwriting where the crossbar of the t doesn’t touch the upright, like Mrs Thatcher’s, is that of an impatient person. Hire them. They get stuff done.

13. Someone who has unexpected upper-case forms for lower-case letters, often R and Q, would jump out of an aeroplane, fuck a pig, steal and drink the homebrewed absinthe of a Serbian warlord, just to see what the experience was like. Go for a drink with them. Just not in Serbia.

14. Anyone who puts a loop on their ascenders in b, d, f, h, k, l, and t is either an American who went through the Palmer programme or someone who puts on their pyjamas and bunny-faced slippers to watch The X Factor with a nice cup of cocoa.

15. If there are big gaps between your words as you write, then you’re a little bit lonely. If your words come close together and even join up, then you’re more likely to be gregarious.

All this is not very systematic. It comes from decades of observation and mindless prejudice, and in some cases the single source of the observation is clear to me. But the skill of reading character through handwriting has been developed over hundreds of years. Its specific insights into aspects of handwriting have hardened into firm principles, and have been used for a number of purposes. Graphologists often make a good living through various applications of their skill. They may be called upon by the courts to pass judgement on the authenticity or otherwise of a handwriting or a signature. They may be employed by companies to examine the handwriting of candidates for a job, to explain what signs of strength and weakness they have discovered. Or they may be used to give a sort of mock-occult reading of someone’s handwriting for their personal interest and curiosity – a sort of palmistry with, it must be said, more reliable results.

It may seem peculiar that the legal/forensic and character-reading side of the graphologist’s trade are practised at the same time. It would be grossly improper, for instance, if a graphologist said that he discerned a criminal or a psychotic personality in the handwriting of the man in the dock. But these strands of graphology developed more or less at the same time. Graphology started as a means of distinguishing the extraordinary – the genius and the criminal. What you were like, and what people could be like, was the driving force behind graphology from the start.

Before the nineteenth century, handwriting was not thought of as something which was particularly individual. Now that we communicate almost entirely through typing, we may be in the process of stripping writing of those individual associations again. Before the very end of the eighteenth century, it didn’t seem at all desirable, or indeed probable, that handwriting was one of those things which separated men out from each other. People learnt to write in a particular school, and practised until they could execute the style of that school, more or less anonymously. They wanted to turn themselves into typewriters, or word processors, and different styles of handwriting were akin, as it were, to fonts, just as we now distinguish ourselves only by our choice of words and our choice of pre-prepared fonts. Of course, this avoidance of the individual style was not always completely executed, and people could always be distinguished by their writing. We know this, among other things, because of a dirty joke in Twelfth Night as Malvolio reads a forged letter from his mistress, Olivia: ‘These be her very c’s, her u’s and her t’s, and thus makes she her great P’s. It is in contempt of question her hand.’ It was not until much later, however, that this individuality began to be seen as important, and later still that it started to be interpreted as a clue to what people might be like as human beings.

The eighteenth century was interested in the ways in which the personality reveals itself through external means – the pseudo-science of physiognomy, in which a criminal or a noble character is shown in the face, and the even odder one of cranium-reading, or phrenology, according to which if you had a big bulge at a certain point, it showed you were musical. More productive was the study of gesture at the time. Previous ages had settled for a survey of how ladies and gentlemen moved, and presented the facade of gentlemanly behaviour as an ideal for study.* The end of the eighteenth century started to think of gesture as something which revealed thoughts and emotion, and, to a certain extent, character. When, in Maria Edgeworth’s Patronage, we are told of Lady Jane Granville that ‘in all her Ladyship said, in every look and motion, there was the same nervous hurry and inquietude’, we see a growing interest in the ways in which people’s outer crust gives away their inner concerns. That interest would soon spread to the ordinary person.

With regards to writing, it was not altogether clear that people wrote in individual ways. The principle that a person could be identified by their writing was established in English law in 1836.† It had been suggested as early as 1726, by Geoffrey Gilbert in The Law of Evidence, that the differences between men’s handwriting could serve to identify them. By 1836, the question was settled: a handwriting was individual, and possessed something called ‘the general character of writing, which is impressed on it as the involuntary and unconscious result of constitution, habit, or other permanent cause, and is therefore itself permanent.’1 The power of handwriting, thus impressed on the reader in a permanent way, had an awesome authority.

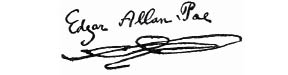

It was not just in the legal arena that a handwriting’s individuality was being examined. This was the age of the cult of personality, and of the autograph collector. The odd hobby of acquiring the signatures of famous, notorious or completely unknown figures rose to great heights in the nineteenth century. Some of the collections amounted to more than 100,000 individual signatures, and were sold for large sums of money. In an essay of 1840, Edgar Allan Poe examined some autographs of famous literary figures, and suggested that ‘a strong analogy does generally and naturally exist between every man’s chirography and character.’ He took the opportunity to talk about some celebrities of the day, in sometimes rather sharp terms: you feel that his view of their literary qualities preceded his analysis of their handwriting. The worst thing that can happen to a writer is that their hand shows no individuality. The genius, it seems, should reveal his character through the strokes of his pen. William Cullen Bryant had ‘one of the most commonplace clerk’s hands which we ever encountered.’ The forgotten poet Rebecca Nichols’s writing was ‘formed somewhat too much upon the ordinary boarding-school model to afford any indication of character’. Another writer, David Paul Brown, had trained as a lawyer, and this, Poe thought, had suppressed any kind of character other than that of the professional class. When Poe admires someone, you can’t but feel that he is not really describing the handwriting: William Ellery Channing, a clergyman, has writing with ‘a certain calm, broad deliberateness, which constitutes force in its highest character, and approaches to majesty’.

People like Poe might be on to something. The qualities which he identifies – boldness, conventionality, unpretending simplicity, deliberateness – are surely ones which we have privately identified ourselves in reading the handwriting of a stranger. It’s true that it is hard to see what led him to the conclusion in each case, but there is no reason to think that Poe was not sincere, or that his mass audience thought that what he had identified was implausible or random. But there was a gap between the handwriting and his impression of it. Now that many people thought that the individual character was manifest in handwriting – even if it was only a character impressive for its commonplace nature – and that many people might agree, in general terms, on the impression given by a man or a woman’s handwriting, the time had come to move beyond the general, and to produce a systematic, detailed guide to the elements of handwriting, and what they might mean.