8 ~ Vere Foster and A.N. Palmer

One of the most successful of these better ideas in the UK was inspired by Lord Palmerston, the great Foreign Secretary and Prime Minister.* Palmerston, in the course of a busy life, found time to concern himself with handwriting, and said once very strongly that ‘Children should be taught to write a large hand and to form each letter well, instead of using fine upstrokes and firm downstrokes that looked like an area railing, a little lying on one side.’† The object of Palmerston’s theory was a friend called Vere Foster, who took the instruction seriously. He produced a series of copybooks which were put into immediate circulation, and survived in British schools for the best part of a century.

Vere Foster firmly believed that traditional copperplate, as specified by penmasters like George Bickham, was pursuing an impossible aim. Foster preferred to take ‘real free writing’ as his model. His copybooks look very artificial to us now, but there was a strong, idealistic, simplifying spirit behind them, which took public service as its goal, and the furthering of the carrière ouverte aux talents as a good beyond questioning.

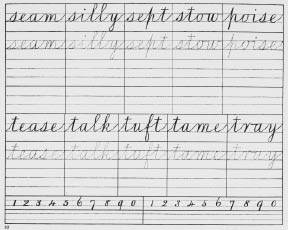

A page of exercises from a Vere Foster copybook.

The age that produced Vere Foster also produced the Northcote Trevelyan reform of the Civil Service. In 1857, Dickens had published a novel, Little Dorrit, which contained a savage satire on the conduct of public life – the Circumlocution Office, staffed, it appears, solely by offshoots of the Tite Barnacle family. Unexpectedly, Little Dorrit was the best-selling of all Dickens’s novels in his lifetime: there was clearly something in the air.

Vere Foster’s copybooks are a minor, but very interesting, contribution to the vast reform and opening up of public service, and the slow movement towards universal education, from where a boy from the humblest background could (ideally) become a responsible public servant. Northcote Trevelyan utterly transformed the British civil service, away from the values of patronage and idleness which Little Dorrit so powerfully portrays. The system that would serve the values of competitive examinations and the reward of merit, regardless of connections, was slower to emerge. But one of the key components of this was a system that would teach children how to write legibly and competently. Vere Foster was ideally placed to deliver this. By 1870, written tests for copy boys and clerks were introduced into the civil service. Before long, the requirements of Vere Foster were being identified as ‘civil service hands’, a term which seems, as late as Reginald Piggott’s Survey of 1958, to need no explanation.

In America, the next stage of handwriting to emerge came from a very similar place to Spencer’s chain of franchised disciples. In some ways, the appearance of the results is similar. But the originators of the style of writing thought of themselves as modernistic, simplifying, clarifiers. They regarded the copperplate style as ornate and outdated. Away with it!

Unlike Vere Foster, whose aim became identified as the public service, his American counterparts focussed on the practice of business, commerce, and independent-minded moneymaking. From the 1890s onwards, the American penman A.N. Palmer worked through the well-established methods of business colleges, lectures, and correspondence courses. It was the golden age of salesmanship, of aspiration, of getting by and getting on, and one thinks of Herbie in the Jule Styne musical Gypsy, going from town to town with a pocket full of badges attesting membership of various business societies, declaring himself an Elk or an Oddfellow, as opportunity presented itself.

Civil Service hand, by a writer aged six.

Between the 1890s, when Palmer published his first manual, Palmer’s Guide to Business Writing,* and the 1910s, Palmer’s simplified and rapid methods took over American handwriting schooling, and produced a completely new style. In some respects, the style remains in place to this day, despite the last Palmer school having gone bankrupt in the 1980s. If the Spencer style remains the admired ancestor of American handwriting, the Palmer manner and its direct offshoots remain a living presence as an idea of good handwriting for many Americans. When we English think of an American handwriting, with the loops and efficient forward dynamism – like the example shown opposite – it’s Palmer we’re thinking of.

Palmer’s aim, like Spencer’s, was efficiency in a business world. The demands of business had increased enormously since Spencer’s day, which now seemed the product of a more leisured age. It is the story of handwriting since the dawn of time. Florentine scribes in the Medici counting houses in the sixteenth century had no time to be writing uncial hands, and took to what we call italic; copperplate was a more efficient way of writing than before; and we don’t have time to be writing in taught hands, so we’ve given up altogether. In Palmer’s case, he assured his readers that an elaborate copperplate hand takes time to produce, and cannot be speeded up. Whatever its legibility for the reader, it does not enable the writer to work with rapidity. The new writing style would be plain and legible, and also rapid. Its proponents liked the idea of ‘real, live, usable, legible and salable penmanship’ which would be ‘no more beautiful than is consistent with utility.’1

The 1950s notebook of LAPD Sergeant Con Keeler. The names and addresses of notorious gangsters – including Mickey Cohen – can be seen.

The new style aimed to get it down quickly. It was a handwriting for the Gilded Age, when elevators were enabling the construction of buildings in Kansas City fifteen storeys high and the full potential of speed was being realized in all sorts of ways. As Palmer’s potential for speed was being realized, the first automobiles would be seen on the roads; during the rise of the style, ‘Jacky’ Fisher, the British First Sea Lord, would be commissioning and building a whole new fleet of warships of incredible velocity and ferocity; before Palmer’s principles triumphed, men would take to the skies.* Efficiency, speed, ugly clarity and consistency: that was the future of writing.

With the same clarity of application that he expected from his pupils, Palmer produced some pseudo-scientific truths and some truly gruelling exercises to enable the student to enter into his prescribed style. Far more than any previous handwriting entrepreneur, he examined the movements necessary to writing. He concluded that handwriting was an athletic activity, which involved much more than the hand.

It became an item of faith with Palmer that good handwriting was produced with movements of the whole arm. The use of the whole arm would avoid writers’ cramp, and enable us all to go on working late into the evening tirelessly. Palmer talked in terms of blood and muscle, rather than pebbles and petals and waves, seeming to think of a physical movement – from the brain, down the neck, across the muscles of the shoulder, down the muscles of the arm, and then through the hand (basically unmoving) and fingers, and down the pen, as if the ink reservoir were just a continuation of the body’s arteries. He spoke of handwriting, not emerging from the nib, but ‘operating along the muscles of the arm.’2

Posture was dictated in extraordinary detail by Palmer and his successors. As late as 2000, we hear of an elementary school teacher in Detroit saying, ‘Where do your feet go when we do D’Nealian?* Flat on the floor, that’s right.’3 Probably you write as I do, with the movements of the body not extending much further up the arm than the wrist. Palmer was certainly correct, that the small movements of the hand are tiring, and, much repeated, might even be damaging. Such grim effects as carpal tunnel syndrome hit inefficient handwriters, pianists and those who write on laptops, with the characteristic tiny movements of the hand – old-fashioned typewriters are much better for you, demanding much larger hand movements. I’ve written the last three pages by hand, and I can feel an ominous tightening and ache on the inside of the wrist, and at the bottom joint of my little finger where it curls under and makes a cushion for the pen.

Try Palmer’s whole arm movement, and it does feel refreshing to write from the shoulder, even without trying to imitate his letterforms. It has some curious effects on your writing, however. I immediately find that my handwriting gets bigger, for instance. I press much less hard on the paper, and the tip of the pen glides across the page. Interestingly, it becomes much less natural to lift the pen in the middle of words, or even between them. If I write the word ‘unimportantly’ in my usual handwriting, it comes out like this – U ni mpor tant ly – four breaks in one word:

![]()

If I try to write it from the shoulder, my whole arm moving, it comes out very readily in one movement, every letter joined together. Weirdly, without attempting to imitate Palmer’s letterforms at all, my handwriting has, in an independent-minded way, developed some of the same characteristics. There is suddenly a bold loop under the p, where it normally just drops and stops. The y at the end, amazingly, just seems to find it perfectly natural to loop and close, in rather an extravagant way. Those loops and joins in Palmer’s style of writing which seem so anti-functional to us, so at odds with Palmer’s message of pared-down efficiency, are in fact serving an efficient end. The name of that end is whole-arm movement.

Palmer’s teaching methods seem decidedly strange to us, but hundreds of schools stuck with it for decades. There was the devotion to pre-writing shape-making – students were meant to sit for hours making repeated ovals, looping and looping, and to devote as much energy as they could spare to what Palmer called ‘push-pull’ exercises, confronting the fundamental problem of handwriting, that sometimes the writer has to pull the pen across the page, and sometimes laboriously push it. The idea was that after you had done this for long enough, your arm would possess a sort of memory of its own. It would be basically impossible to make anything but the correct shape when you wrote, and impossible to grow tired while writing. We have the word of a large number of Palmer students, however, that as soon as the teacher turned his back, it was much more natural to produce a sort of stab at the Palmer letter shapes without moving anything higher than the wrist. Once Palmer’s methods had started to decline in popularity, the faults of the system started to become obvious. One 1940s graphologist, who perhaps had his own professional reasons for disliking a system which suppressed personality and imposed a military-style correctness on handwriting, wrote that ‘Adults still remember [Palmer’s] penmanship lessons as a source of acute discomfort and frustration. Even with such drills, Palmer’s remains a tiring and slow method of writing. It is tiring and slow because it does not permit the writing hand to relax its muscles … And this slowness is furthered through an abundance of superfluous and left-tending strokes, of sudden changes in direction, of counterstrokes, and of elaborate, though useless and time-consuming finals.’4*

From our perspective, there is one thing extremely odd about every one of these proposals to shape the handwriting. They start from the very first day, insisting that children should learn to write by joining up the letters and writing whole words. Cursive handwriting is not only the goal for Palmer, Vere Foster, Bickham and Spencer: it is the only way anyone could ever be permitted to begin to write. Change was brewing.