Thankfully, mass incarceration emerged as a high-profile issue in our national conversation during the 2015-2016 presidential nominating season. The discussion took place among the candidates pursuing the Democratic nomination more so than those seeking the Republican nod, but the fact that mass incarceration was mentioned at all—and identified as a wrongheaded policy—was an important marker of progress in the ongoing struggle to upend the Prison Industrial Complex. Perhaps we are entering an era in which the “tough on crime” mandate across the two-party system is waning. And if that is happening, we can begin to imagine a future in which the PIC is dismantled. We can certainly hope that this is the case and demand that our political leaders take notice of the data that expose the problems in our criminal justice system.

In February 2016, a Black Lives Matter (BLM) activist named Ashley Williams disrupted a $500/person fundraising event being hosted by the Hillary Clinton campaign. All Williams did to make her point was hold up a sign with words from a speech given by then First Lady Hillary Clinton in 1996, during the reelection campaign for her husband, President Bill Clinton. “We have to bring them to heel,” the sign read.

Hillary's speech had come two years after the signing of President Bill Clinton's infamous 1994 Crime Bill, or the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act. The most sweeping federal crime legislation in U.S. history, his initiative directly fed the monster that the PIC was already on its way to becoming. In support of those policies and her husband's candidacy for reelection, the First Lady referred to certain American youth gangs as “superpredators” and suggested, “[w]e can talk about why they ended up that way, but first we have to bring them to heel.”

The historical context of the quote is important to remember. It was the mid-1990s, and the national perception of crime and crime rates had not caught up with data clearly showing a decline in violent crime—even among urban youth associated with gang culture. But facts about crime don't always matter as much as perceptions of crime do; nor do the facts always matter in a presidential campaign. In short, First Lady Clinton was playing into a well-worn script in American politics—that being tough on crime was essential for political leaders to earn the trust of the electorate. Despite evidence to the contrary, the American mainstream harbored irrational fears of an imminent future in which nihilistic young predators—inevitably young Black men—would control urban communities through violence and drug dealing. Hillary Clinton's speech that day was designed to shore up President Bill Clinton's bona fides as a tough-on-crime Democrat poised to bring animalistic predators “to heel.”

The fact that Ashley Williams and the Black Lives Matter movement would seize upon this language ten years later, and use it to push presidential candidates to wrestle with the problems of the Prison Industrial Complex, is perhaps as significant as the context in which the comments were originally made. While some of the national news media did not cover the disruption, and others tried to explain away Williams' sign based on the critical context of the moment, activists engaged in revealing the problems of the American criminal justice system were fully aware of the role that language plays in supporting the policies that exact justice unequally in terms of race, class, and gender.

The First Lady's comments still rankled. Her refusal to understand or discuss why young people turn to crime in the first place remained a telling reflection of the problematic ways in which crime policy too often is made. In the absence of real information about eroding public schools, the outsourcing of manufacturing and service jobs, the impact of regional trade agreements on the American worker, and a host of other factors, the notion that hordes of young people are predisposed to committing violent crimes reinforces the shallow thinking that some young people—young Black people—are just naturally criminal. Without any recognition of social and economic context, the notion that “We can talk about these things if we want to but . . .” simply suggests that the only way to address the problem is through punishment and incarceration.

In some ways, the dismissal of (or failure to understand) the facts is more damning than the dehumanizing language of the statement itself. It reduces policy formation to reactionary platitudes that ignore the structural realities that cultivate and produce certain behaviors. No one—not then and not now—can argue with the fact that concentrated poverty and high crime rates go hand in hand. Not acknowledging that fact honestly and upfront is a disingenuous play into people's fears about crime in society.

Obviously it does not address the social problems associated with criminality and the PIC in a civilized, humane way to think of bringing young people “to heel.” The phrase typically refers to the discipline, training, and control of animals, not human beings. Dogs and horses are “brought to heel.” BLM activists understand that this is precisely the type of language that facilitates the inhumane treatment of the incarcerated—especially young people. Moreover, the thinking that underlies this kind of language is a direct reflection of the racial biases that contaminate the entire system and have done so since the earliest iterations of the American prison system.

Clinton was not speaking off the cuff. She took the term “superpredator” from a political scientist who became nationally recognized in the 1990s for his theory of juvenile violent crime. The scholar, named John DiIulio, distanced himself from his own research in 2001, just as he was appointed to direct the George W. Bush White House Office of Faith-Based and Community Initiatives. In the meantime, DiIulio argued that a combination of demographic shifts in the population (i.e., a surge in Black male youth) and the socialization of many of these youths by older, more violent Black people in their neighborhoods was, in effect, producing what he called “a new generation of street criminals—the youngest, biggest and baddest generation any society has ever known.”55

The vision of a future dominated by marauding superpredators soon took hold in the American political imagination, with terrifying political consequences. Support for tough-on-crime policies continued unabated. Funding for the War on Drugs and the outsourcing of private prisons likewise continued to thrive into the next decade. Whether or not political leaders and policymakers are willing to admit it, once again the claims of an academic—purportedly supported by sound research—set in motion a series of policy recommendations, laws, and practices that put an inordinate, inequitable number of poor people of color into the Prison Industrial Complex. Fear and prejudice prevailed.

This superpredator theory was, in the end, soundly debunked. The juvenile crime rate dropped by more than half over the period that DiIulio predicted it would skyrocket. In the meantime, however, the popularity of the concept was one of several factors that facilitated a national movement to try youthful offenders as adults for violent crimes. Legislators heeded the call. Between 1992 and 1999, 49 states and the District of Columbia made it easier to try juveniles as adults.

Some states removed consideration of youth altogether, replacing discretion with compulsory triggers. By 2012, there were 28 states across the nation that were handing out mandatory life-without-parole sentences to juveniles.56

Nowhere was this theory adopted into policy more pervasively than in the states of Pennsylvania and Louisiana. Pennsylvania, according to information collected in 2015 by the Phillips Black Project, a nonprofit law organization, had the most prisoners serving juvenile life sentences—376. Louisiana followed closely behind with 247, representing the highest per-capita rate in the nation. Nearly 200 of the 247 juvenile life sentences in Louisiana were given to African Americans.

The superpredator theory has remained stuck in the collective consciousness of the American criminal justice system. Only recently, in 2012 and 2016, has the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of juvenile humanity and the possibility of rehabilitation by banning life-without-parole sentences for juveniles. Still, young people of color—especially the poor—have continued to be vulnerable to the policies that power the PIC. In the end, it comes to down to one simple fact: It is easiest to demonize those who don't yet vote and who, because of our criminal justice policies, may never get the chance.

Perhaps the best way to sum up the pervasive consensus for this kind of PIC rhetoric and practice in American politics is that Clinton's rival for the Democratic nomination in 2016—the “democratic Socialist” Bernie Sanders—voted for the crime bill in 1994 and, like Hillary and Bill Clinton, came to regret his support.

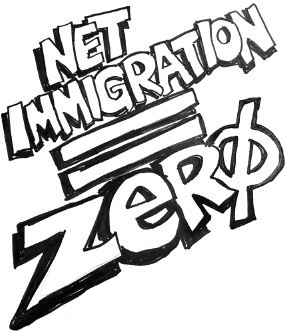

Another realm of federal policy that tends to have a disparate impact on young people is immigration. Like the superpredator theory and its legislative consequences, American immigration policy in the late 20th and early 21st centuries relies more on fear and racism than it does on the actual facts of immigration.

In the 2010s, net immigration into the United States has been close to zero; and there has been no net immigration from Mexico. Yet the rhetoric of building walls and deporting “illegals” continues to be the order of the day in the national discourses on immigration policy. From the nation's earliest immigration policies through the 1980s, crossing the U.S. border illegally was considered a minor civil offense. In the 1990s, however, shadows of the Prison Industrial Complex began creeping into ideas about immigration. The policies that followed contributed significantly both to the prison population and to the role of private corporations in the American penal system.

Without any evidence that increased penalties would reduce unauthorized entry into the United States, federal policy makers in the mid-1990s made illegal border crossing a criminal offense. Prosecutions for illegally crossing the border rose from less than 4,000 annually at the beginning of the Clinton administration to more than 31,000 per year during the George W. Bush administration, skyrocketing to 91,000 in 2013 under President Barack Obama.57 The rush of new prosecutions contributed in no small measure to the expansion of the Prison Industrial Complex into its grotesque current form and has had a direct impact on the lives and families of undocumented youth.

Most immigrant families, documented or not, enter the United States for work-related reasons. Many of those who enter the country for economic advantage are lured by the promise of jobs with large corporations that deliberately circumvent labor law and hiring practices. Once again, the facts of the situation are often left out of the discourse. And so, true to form for the Prison Industrial Complex, the policies thatmade the criminal justice system more aggressive toward immigrant communities of color was soon producing conviction rates that outstripped the capacity of federal prisons and detention centers to accommodate the influx of newly minted convicts. The Federal Bureau of Prisons responded by outsourcing the problem to private corporations. Today, the Corrections Corporation of America (CCA) and The GEO Group (formerly Wackenhut) own and operate nine of the 11 private detention centers where the population of convicted undocumented immigrants is housed.

The Bureau of Prisons thus relies on private corporations to manage a problem of the government's own policymaking. The government spends in excess of $600 million annually to outsource the consequences of a broken federal immigration policy to private corporations with a track record of cutting corners rather than cutting costs. One of the recurring problems in the immigrant-only private prison system is an abysmal record on health care for inmates. Reporters and activists have uncovered incidents and conditions best described as atrocities that are endemic to the privatized sector of the PIC. While politicians make hay over the need for walls, the lack of humane levels of health care has been left out of the debate about the nation's immigration policy. And, as in the case of most of unforeseen consequences of the PIC, it is children who suffer most from the deficiency.

Like our broken immigration policy and the political rhetoric of toughness on crime, another aspect of the PIC with a disparate impact on American youth is the tortuous practice of solitary confinement. Solitary confinement is the practice of incarcerating inmates in a small cell for up to 24 hours per day, with limited or no contact with other human beings. It bars family and conjugal visits, reading materials, educational programming, and medical treatment. Prisoners forced into solitary confinement are often physically abused, tortured, or mistreated in other ways. Some are subjected to sensory deprivation, various forms of restraint or physical confinement, and the periodic use of stun guns and stun grenades.58

Like most of the worst aspects of the Prison Industrial Complex, the widespread use of solitary confinement began in the 1970s and continued to expand through the “heyday” of the PIC from 1985 to 1994. Today, the American prison population includes more than 80,000 inmates in solitary confinement.

A number of side effects, both physical and mental, are derived from ongoing isolation and physical punishment over the course of days, months, and sometimes years. Among the psychological consequences are paranoia, hallucinations, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicidal inclinations.59 Most of the mental effects have a greater impact on young inmates because their brains are still developing and because of their youthful vulnerability.

In certain systems and in some regions of the country, officials of the PIC acknowledge the inhumane treatment endemic to all forms of solitary confinement. Some of this recognition came to the state of New York after the tragic case of Kalief Browder. In 2010, at the age of 16, Browder was arrested for allegedly stealing a backpack. Charged with second-degree robbery, he refused to plea bargain and was unable to make bail. As a result, he was incarcerated for three years without ever being convicted of a crime. Held at the Rikers Island Prison Complex in New York City, a group of jails notorious for their draconian conditions, Browder spent two thirds of his time there in solitary confinement. It was later reported that Rikers guards starved him as punishment for repeated suicide attempts. Videotapes showed officers and other inmates pummeling and kicking him.

As brought to light by journalist Jennifer Gonnerman in the pages of The New Yorker magazine, Browder's plight dramatized the devastating long-term effects of solitary confinement and became a symbol of the broken criminal justice system. Released in May 2013, Browder tried to get his life back on track but never fully recovered from his prison experiences. In June 2015, he committed suicide by hanging himself at his parents' home.

Kalief Browder remains a living symbol of the ways our Prison Industrial Complex treats young people and the brutality of solitary confinement. That a teenager could be confined for three years—most of them in solitary—without even being convicted of a crime begins to tell us how broken the system is, to demonstrate the inordinate backlog of cases in a criminal justice system the size of New York's, and to underscore the inherent bias in bail levels for poor and working-class citizens. While Browder's story drew national attention and put pressure on political leaders to initiate change, his experiences should serve as an ongoing reminder of just how horrific the Prison Industrial Complex can be to our children.