The rates of recidivism for the Prison Industrial Complex reveal at least one unfortunate fact: American incarceration is no longer invested in rehabilitation. Recidivism—defined as the rate at which released prisoners return to prison, or the percentage of released prisoners that return to prison—represents a powerful referendum on why the PIC must be abolished and an important rationale for why the policies that shape and inform mass incarceration must be eradicated.

A 2014 study conducted by the U.S. Department of Justice found that two thirds of individuals released from U.S. prisons in 2005 were rearrested within three years; three fourths were rearrested within five years.60 If the majority of those who are imprisoned end up back in prison within five years, then perhaps the PIC should be recognized as a system that benefits from and promotes the warehousing of human bodies and that, in many cases, the facilities of incarceration are actually preparing prisoners for more criminal activity and an ongoing life of confinement and/or enslavement.

As discussed in earlier chapters, the origins of the American penitentiary—both in name and in social and institutional structuring—suggest that jails and prisons should serve as spaces of reflection for members of society who may have lost their way. Legal scholars and the social architects of the early United States believed in the possibility of redemption through silent reflection, labor, and isolation. It was not until well into the 20th century, with the advent of “law and order” ideology as a fixture of American politics and the growing sentiment that criminal behavior is irredeemable, that the social context for rampant recidivism began to be established. Robert Martinson's infamous 1974 article “What Works” actually suggested that nothing works in terms of rehabilitating prisoners. His impact on public policy and the public's perception of crime and the limits (or impossibility) of rehabilitation was profound and long-lasting. Indeed it could be argued that Martinson's work, in tandem with President Nixon's initiation of the War on Drugs, laid the ideological foundations for recidivism in the PIC—especially for drug offenders.

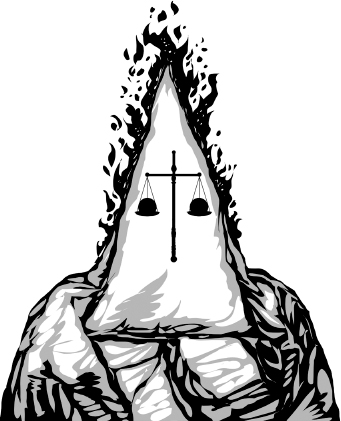

We can understand this unfortunate set of circumstances through the eyes of professionals on all sides of the legal process. In his book Let's Get Free (2009), former criminal prosecutor Paul Butler takes a searing look back at the profession of which he was once a part. His experiences as a prosecutor made him skeptical about the viability of prosecuting crimes that are socially perpetual, like prostitution and drug possession. Butler paints a picture of prosecution lawyers as being game-oriented, focused on winning by any means necessary. In his view, the overly aggressive nature of modern-day criminal prosecutions, the outrageously high plea rate, and the racial and class biases in the system all add up to one thing: The U.S. criminal justice system practices “legal hate.”

High recidivism rates reflect the legalized hate practices of the PIC—solitary confinement, forced labor, rape, and gang violence. There's no mistaking the truth. Conditions within prisons directly contribute to the high rates of return. Moreover, according to some studies, more than half of all recidivists are charged with more serious crimes than their initial cause of entry into the PIC. This intimates an awful possibility: that the PIC is not rehabilitating criminals, but it is training them to become even more hardened and more violent criminals. Intended or not, recidivism feeds the PIC and simultaneously reveals its most critical secret: the PIC feeds off of itself.

It is somewhat ironic that we rely on the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) for so much critical information on the Prison Industrial Complex. In this case, the data on recidivism is key to our understanding of the failures of the PIC and our withering social investment in the possibility of rehabilitation. In assessing these and other figures, it is important to remember the DOJ's role in the PIC has not always been constructive or objective. In the early 1990s, the department deliberately exaggerated the threat of violent crime in America, making an artificial case for more incarceration.61 And to make a case for the construction of more prisons, the DOJ cited a 1987 government study indicating that incarcerating just one prisoner saved society more than $400,000 per year. If this sounds too good to be true, that's because it is not true. The “study” in question was based on the fantastic claim that an alleged criminal left un-incarcerated would commit over 180 street crimes per year, at a cost of about $2000 per crime. The researchers eventually retracted their claims, but the damage may have already been done. The early 1990s brought the rapid expansion of the PIC, with the initial data on recidivism reflecting the nation's belief that locking up criminals was the only way to lower crimes rates.62

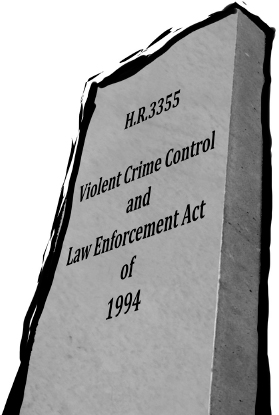

The entire history of the PIC has seen repeated, marked dissonance between research, research accuracy, and the policies of mass incarceration. One critical issue directly related to recidivism rates is that of education in prisons. Among the measures included in President Bill Clinton's 1994 Crime Bill—epitomizing and institutionalizing the “tough on crime,” law-and-order politics of the time—was the elimination of Pell Grants for federal prisoners. Pell Grant funding provided support for prisoners to take college courses. Individual states followed suit, and by 1995 only about 2% of college programs in American prisons were still in place.63

It hardly takes a government report or academic study to understand that educating prisoners can expand their options and improve their quality of life after release. But public sentiment toward criminals and prisoners during the 1990s was shaped completely by the law-and-order ideology that had triggered the War on Drugs. For too many Americans, providing educational support to incarcerated criminals was inconsistent with the principles of punishment and confinement. The Crime Bill of 1994 certainly seems archaic and inhumane in hindsight, as it exacerbated the worst aspects of the PIC by expanding privatization and diminishing the last vestiges of the possibility of rehabilitation. Yet the legislation was well-received by politicians and the public at the time, even though the inherent racial and class biases of the PIC were readily apparent.

Studies do indicate, of course, that education and access to education in prison reduce recidivism and produce more favorable reentry outcomes for former prisoners trying to make (or remake) a life outside the PIC. According to an Urban Institute study in the early 2000s, participants in vocational and educational programs in prison were, upon release, more employable, employed for longer periods of time, and committed fewer crimes than their counterparts who did not take part in such programs.64 There is little question that education in prison reduces recidivism rates and limits the PIC's cyclical processes of incarceration.

Since the early 2000s, public sentiment in the United States has started to shift with respect to the PIC. In addition, the exorbitant costs of the PIC in both human and monetary capital have forced many states to adopt more humane and economically sensible policies to address the problems of mass incarceration. Contemporary studies have contributed to a mounting body of data once again suggesting that programs within the prison system might help reduce recidivism. Many of the same studies also suggest that alternatives to incarceration might be more effective at rehabilitating nonviolent offenders—but that could be the subject of another entire book.

In 2008, the U.S. Congress passed the Second Chance Act (SCA), which supports state, local, and tribal governments and nonprofit organizations in their efforts to reduce recidivism and improve outcomes for people returning from state and federal prisons, local jails, and juvenile facilities. “Passed with bipartisan support and signed into law by President George W. Bush on April 9, 2008, the legislation authorized federal grants for vital programs and systems reform aimed at improving the reentry process.”65

The focus on reducing recidivism and providing more robust support for reentry programs are the cornerstones of what, by some accounts, is a fairly anemic prison reform program proffered at the federal and state levels. With respect to recidivism, a few final points are worth exploring here briefly.

For the most part, when people think about recidivism rates in the PIC, the general assumption is that re-incarceration is driven largely by criminals just being criminals—that they continue to commit crimes after being released because they are naturally and irreversibly criminal. Upon closer investigation of the PIC, however, one finds other factors within the system itself that drive recidivism rates.

Prior to the Reagan administration in the 1980s, there was still a small modicum of hope for rehabilitation and redemption in the PIC. But once President Reagan doubled down on the War on Drugs and once the ideology of law and order was invigorated with new rhetoric and policy initiatives, the shift to a purely punishment-driven PIC was cemented. The transition was clearly reflected in changes to the approach to parole and probation. Under the rehabilitation ethic of the penitentiary system, and throughout the early history of parole and probation in America, parole and/or probation officers were committed to keeping their clients out of jail. Believe it or not, mandatory drug testing was not an original feature of probation. But the law-and-order crowd sincerely believed that parole boards were too lenient and that too many “hardened criminals” were not serving long enough sentences.

Reagan's War on Drugs changed the fundamental approaches to both the parole and probationary processes. In the 1980s, law enforcement institutions enhanced the role of what was referred to as “technical violations,” making it easier to re-incarcerate paroled prisoners and those on probation for various offenses. Technical violations are exactly what they sound like—violations of a rule or regulation that should be considered technical or petty depending upon perspective. In the present context,

[t]echnical violations can include missing a scheduled meeting with a parole officer, failing to tell the parole officer of a change in employment or residence, failing to disclose parole status to an employer or landlord, being out of your county without permission, and(or) getting a positive drug test.66

Under the new approach, a positive drug test even for a former prisoner previously convicted of a drug-related offense might still constitute grounds for re-incarceration in some parole cases. In effect, parole and probation tactics during the 1980s became much more aggressive, contributing to mass incarceration rather than serving the original purposes of facilitating rehabilitation and reentry into society.

As of 1980, only about 17% of prisoners in the United States were serving time for parole violations. By the end of the 1990s, fully one third of prisoners had been re-incarcerated for parole violations; two-thirds of those had been re-incarcerated for technical violations.67

Of the many failures of the PIC briefly catalogued in this book, the shift in the administration of parole and probation ranks as one of the most profound. It underscores yet again the abandonment of rehabilitation as a guiding principle of the criminal justice system, and it highlights the incapacity of the system to act fairly and to treat humans with patience and dignity. This is especially devastating given the inherent class biases in our criminal justice system and the inextricable links between lack of educational opportunity, mental health challenges, and mass incarceration.

Most studies show that the number of people released from prison who wind up returning within three years typically hovers around 40%. This tends to be a statement more about the scarce opportunities these former offenders find on the outside than their predilection for crime.68

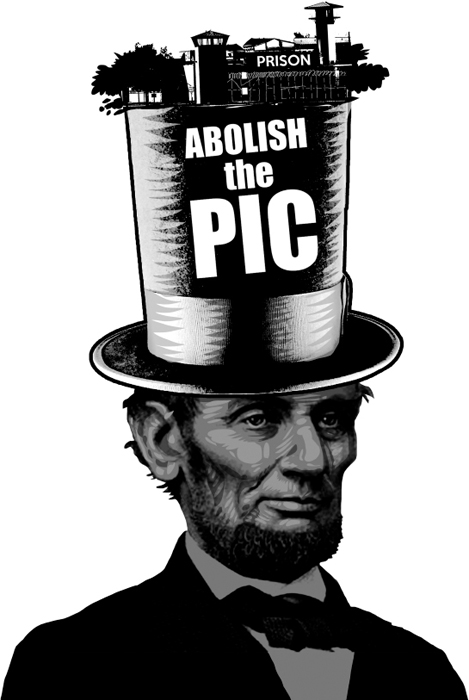

The data on recidivism make a powerful and compelling case for radical reformation of mass incarceration policies and the dismantling of the constitutive components of the Prison Industrial Complex. Reform versus revolution is a longstanding debate among progressive grassroots activists. Whether to reform or abolish the policies of mass incarceration and the Prison Industrial Complex has been discussed for decades. A powerful case can be made for the wholesale abolition of the PIC—some of the arguments are laid out in this volume. But abolishing incarceration itself is a much more complex issue, given the conventional assumption that some form of prison system is required in modern society.

Longtime activist and scholar Angela Davis is one of the leaders of the prison abolition movement in the United States. In her book Are Prisons Obsolete?, she argues that prisons

relieve us of the responsibility of seriously engaging with the problems of our society, especially those produced by racism and, increasingly, global capitalism.69

Professor Davis, who has actively fought the PIC since her own incarceration as a political prisoner in the early 1970s, personally understands the racialized history of the criminal justice system and the sociopolitical consequences of not working toward the abolition of the PIC. The obvious model for the prison abolition movement is the movement to abolish slavery itself. Nineteenth-century abolitionists believed in the basic humanity of enslaved Africans and understood the diminishing effects on the humanity of slave “owners” who worked systemically to dehumanize their “property.” The antislavery movement at its peak was a coalition of Quakers, white Northerners, free Blacks, American Indians, and the enslaved who worked together by nonviolent and violent means to bring about the destruction of the “peculiar institution.” So enmeshed was human bondage with the Southern economy that many at the time believed that abolition was impossible—but of course it wasn't.

A number of contemporary scholars, including Michelle Alexander, Douglas Blackmon, and others mentioned in this book, have brilliantly demonstrated the interconnectedness of the policies of mass incarceration, the partnerships in the Prison Industrial Complex, and the legacy of institutional transatlantic slavery. All have been inextricably linked through a complex history in the United States—a nation that built a global capitalist economic system literally on the backs of enslaved Africans, whose descendants have been systematically overrepresented in a prison system that has expanded tremendously in just the last half-century.

So it seems fitting that a new abolition movement is underway, calling for a complete end to the Prison Industrial Complex. The success of this very important movement depends on our capacity to understand the deep histories that inform the construction of the PIC and the deleterious consequences of our failure to dismantle it as soon as possible.

That said, real reform can be a path to abolition, too. In the absence of a collective political will to rethink the role of prisons in our society and to dismantle the components of the Prison industrial Complex, real reform may be a productive option for undoing some of the damage. According to Michael Jacobson, the author of Downsizing Prisons (2006), one of the ironies about real reformation of the PIC is that both privatization and recidivism offer real opportunities to begin shrinking the complex. States that contract with private prisons can cancel, refuse to renew, or resist signing future contracts with private prison corporations like Corrections Corporation of American. They can make it policy not to engage private entities to replace the protections that the criminal justice system is supposed to provide. By eliminating private contracts with corporations that build, own, and manage prisons, a state can also save money. In 2002, Mississippi closed a CCA prison and realized an almost immediate savings of $4 million.70

Directly addressing the challenges of high recidivism offers another opportunity for real reform. Policies rewritten to diminish recidivism rates would eliminate the “technical violation” regulations that make the PIC cyclical for so many paroled inmates. What's called for here is a complete rethinking and overhaul of the parole system. Parole should be administered in reasonable, productive ways based on the tenets of reform and redemption from the early days of the penitentiary. So long as the parole system functions like other aggressive components of the criminal justice system (racial profiling, stop and frisk tactics, no-knock warrants, mandatory minimums, and the like), then it will continue to be a tool of recidivism rather than a process through which prisoners reenter society.

Sentencing reform is critical to any real reformation of the PIC. Advocates and activists must continue to push legislators toward more and more revision of sentencing policy. The goal here is to reform sentencing in a way that funnels nonviolent, lower-level offenders into prison alternatives—giving serious consideration to correctional facilities focused on rehabilitation and community-based practices. Real reform efforts must be organic, emerging in local contexts in ways that address local issues and local concerns. This is especially important for sentencing reform and the challenges of reentry, which are particular to specific communities.

Reasonable sentencing should be another important feature of the prison reform effort. Mandatory minimums should be abolished, as they create overly aggressive, overly empowered prosecutors. They give the prosecution too much leverage in the criminal justice system and, in too many ways, eliminate the power of judges to make smarter judicial decisions. Lastly, sentencing disparities that are either inherently or consequently biased by race, class, or gender must be eradicated.

Long before criminal court proceedings, the tentacles of the Prison Industrial Complex reach deep into poor communities of color through government policies like the War on Drugs and a wide range of aggressive tactics by local law enforcement. Real reform requires an end to racial profiling, the “broken windows” strategy, stop and frisk tactics, and greater diversity within the ranks of police themselves. Militarizing local law enforcement with combat weapons and the equipment of war will also have to be curtailed if the PIC is ever to be reformed. Policing cannot look like warfare if it is to achieve its purpose—to protect and serve—in actuality or in perception.

Indeed there are a great many other considerations for reforming the Prison Industrial Complex, some of them not readily apparent given the overwhelming quantity of data on the prison system itself. Clearly, however, some of the broader societal remedies include a radical reinvestment in public education; ending homelessness and developing more comprehensive affordable housing policies; and decriminalizing certain controlled substances. Given what we know about the War on Drugs, any real reform of the PIC must include the END of the drug war. The War on Drugs is a war on poor people of color, and it has been an abject failure.

Most scholars, reformers, abolitionists, and activists engaged in the struggle to change America's prison addiction also understand that for, all of the possibilities that policy changes represent, real reform must begin with a change in the nation's perception of criminal justice and incarceration. Unless and until the citizenry is ready to wean itself from the abiding sense that punishment is the central purpose of incarceration, the United States will not be able to alter its status as the world's leading incarcerator.

Finally we have to be prepared to humanize criminals, and not just the nonviolent ones. Given the scope of the Prison Industrial Complex—its size (2.2 million inmates), its complexity, and the vast economic investments and profits in the system—only a radical revision of how we view crime, criminals, and criminality can move the needle in the right direction. As antidrug advocates often maintain, a harm-reduction approach to drug abuse—or in this case, mass incarceration—is more likely to yield constructive results.