CHAPTER 3

EXPANDING THE EPIDEMIOLOGICAL LENS FROM PREVALENCE RATES TO CORRELATES

To understand the specific research on students with gifts and talents and suicide, we must first illustrate the current knowledge of suicide among the general population of children, adolescents, and young adults beyond mere prevalence rates. There has been considerable research focused on how to predict completed suicides. From this research, risk factors have been identified. Risk factors are established statistically by correlating different traits, qualities, and behaviors with completed or attempted suicides. Initial studies of risk factors were designed somewhat atheoretically, by analyzing relationships among any variables that could be found and correlated. Over time, the research was improved by including theories of suicide, which were to varying degrees empirically validated, complementing the epidemiological data. Two especially important theories will be discussed in Chapter 4. They represent two different, but powerful theories for making sense out of suicidal behavior. They are psychache (Shneidman, 1993) and the suicide trajectory model (Stillion & McDowell, 1996). Building on these theories, later in the book we will offer a theory for the suicidal mind and suicidal behavior among students with gifts and talents.

It is important to understand not only how many people of different categories are engaged in suicidal behavior, but also to know what is associated (statistically speaking, correlated) with suicide. These correlates are often presented as being risk factors, although, to be clear, correlation is not the same as causation. Quite a bit of research has been conducted to uncover correlates of suicidal behaviors. Rudd et al. (2006) attempted to more fully distinguish between the risk factors and warning signs of suicide. He concluded that risk factors tend to be stable characteristics such as age, suicide attempts, and comorbidity, while warning signs are more transitory states such as psychache and hopelessness. Warning signs will be discussed more fully in later chapters.

RISK FACTORS FOR ADOLESCENT SUICIDE

Gould, Greenberg, Velting, and Shaffer (2003) conducted a review of a decade’s worth of research on adolescent suicide and described the following as significant risk factors:

1. Psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety (referred to as comorbidity, which is very strongly associated with attempts and completions)

2. Substance abuse (can vary in type, but alcohol and other popular depressants are the more common types)

3. Cognitive and personality factors (e.g., hopelessness, coping skills, neuroticism)

4. Aggressive-impulsive behavior

5. Sexual orientation (homosexual, bisexual)

6. Friend or family member of someone with suicidal behavior

7. Parental psychopathology (e.g., depression, substance abuse)

8. Stressful life circumstances (e.g., interpersonal loss, legal/disciplinary)

9. Glamorization of suicide through media coverage

10. Access to lethal methods (e.g., firearms)

Because most of these are self-explanatory, we will only comment on three of them, beginning with sexual orientation (homosexual, bisexual). The risk does not arise from being homosexual or bisexual, per se. Rather, it derives from a person’s lived experience of having a nonnormative sexual orientation in a society that rejects that identity. LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning) youth are at risk for violence because of negative attitudes that permeate the society. These attitudes are the impetus for mistreatment, sometimes even from members of one’s own family (Ryan, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2009). Bullying rates are higher among LGBTQ youth, as well (Birkett, Espelage, & Koenig, 2009). These youth become homeless at a higher rate than their heterosexual peers and have a higher rate of sexual abuse (Coker, Austin, & Schuster, 2010). The compounding effect of rejection results in a higher risk of suicidal behavior among the LGBTQ population, a consistent finding in research (e.g., Grossman & D’Augelli, 2007; Russell & Joyner, 2001). To date, little research has focused on differences in suicidal behaviors or risk factors for the different subgroups, lumping all those together under the LGBTQ umbrella. More sophisticated research in this area is needed to identify how risk factors may differ for each group.

There has been evidence since the 18th century for the risk of number 9 on the list, glamorization of suicide through media coverage. The publication of Goethe’s popular book The Sorrows of Young Werther in 1774, about a young man who died by suicide in response to societal and romantic rejection, was followed by fears and some evidence of imitation suicides that led to a ban of the book in some European countries (Jack, 2014). Suicides that follow a media event, from the publication of a book to news reports of a celebrity suicide have been called the Werther effect. The contemporary television series 13 Reasons Why has been similarly prohibited in some schools and even countries out of fear that young people will imitate the suicide of the main character (Knapp, 2017; Roy, 2017).

Some research has borne out an increase in imitative suicides after such prominent sharing (e.g., Gould & Shaffer, 1986; Niederkrotenthaler et al., 2012). In the month after news reports of Marilyn Monroe’s death by suicide in 1962, there was a 12% increase in the number of suicides across the U.S. (Phillips, 1974). Following the suicide of musician Kurt Cobain, there was considerable attention in the media. For weeks, MTV and other news outlets aired programs about the life, death, and music of Kurt Cobain. This suicide was one of the major news events of 1994, and given the growing competition at the time among the increasing number of 24-hour news stations, the amount of coverage was quite substantial. Although there was not an increase in suicides in the Seattle area in the weeks immediately after his death, there was a significant increase in calls to crisis hotlines (Jobes, Berman, O’Carroll, Eastgard, & Knickmeyer, 1996). The authors attribute this relative success to great attention to responsible reporting, a community call for comforting one another, and a personalization of the suffering Cobain’s death had caused. Media outlets are increasingly being made aware of helpful and harmful practices in the reporting of suicides (John et al., 2017). The World Health Organization (WHO, 2008) offered guidelines for responsible reporting, such as avoiding sensationalizing the suicide and not publishing pictures or descriptions of the methods used.

The third risk factor to be noted is number 10 on the list: access to lethal methods (firearms). Of all of the 10 risk factors, this one draws the most concern from those who believe that it might have an effect on gun ownership. The issue is not about second amendment rights to own a gun, rather it is the fact that when a suicidal person has immediate access to lethal means of death, chances of a successful suicide increase. As noted in Chapter 2, where there are more firearms, rates of suicide are higher. Firearms are extremely effective in a suicide attempt. Based on emergency room statistics in 2001, the case fatality ratio (fatal:nonfatal injury) of successful efforts at self-harm with firearms was 85:15, for suffocation or hanging 69:31, but for poisoning or overdose it was only 2:98, and for cutting or piercing only 1:99 (Miller, Azrael, & Barber, 2012).

Gould et al.’s (2003) research is important because it brings together many previously conducted studies. The 10 risk factors of suicide become an important tool to help us understand variables associated with suicidal behavior. Although not causal per se, in some cases the correlations are quite strong. For example, it is very common for people who engage in suicidal behavior to also be experiencing depression or anxiety. This fact provides guidance about how to intervene to prevent suicide. Unfortunately, however, other correlates such as sexual orientation or whether a family member has completed suicide cannot be changed. Keep in mind that correlation is not causation. Even with the inherent limitations of relying on correlates as risk factors, knowing what these are greatly benefits our understanding and potential to intervene in positive ways to help prevent completed suicides. Note that suicide prevention will be discussed in Chapter 8.

The American Association of Suicidology (n.d.) offered the information presented in Table 9 as an easy-to-remember consensus of warning signs of suicide. Although not exactly the same as the previous list of factors associated with suicide offered by Gould et al. (2003), the “IS PATH WARM” acronym identifies variables that overlap considerably. It also uses language that is less technical, making it easier to read and share with others. It is important to note that millions of people live long lives with one or more of the risk factors we have described. Moreover, trying to predict actual suicide attempts from knowledge of an individual’s risk factors has not been very successful.

Table 9

Consensus Warning Signs of Suicide (American Association of Suicidology, n.d.)

A person at risk for suicidal behavior most often will exhibit warning signs such as:

| Letter |

Represents |

Description |

| I |

Ideation |

Expressed or communicated ideation

• Threatening to hurt or kill him- or herself, or talking of wanting to hurt or kill him- or herself

• Looking for ways to kill him- or herself by seeking access to firearms, available pills, or other means

• Talking or writing about death, dying, or suicide when these actions are out of the ordinary |

| S |

Substance Abuse |

Increased substance (alcohol or drug) use |

| P |

Purposelessness |

No reasons for living; no sense of purpose in life |

| A |

Anxiety |

Anxiety, agitation; unable to sleep or sleeping all of the time |

| T |

Trapped |

Feeling trapped—like there’s no way out |

| H |

Hopelessness |

Hopelessness |

| W |

Withdrawal |

Withdrawing from friends, family, and society |

| A |

Anger |

Rage, uncontrolled anger, seeking revenge |

| R |

Recklessness |

Acting reckless or engaging in risky activities, seemingly without thinking |

| M |

Mood Changes |

Dramatic mood changes |

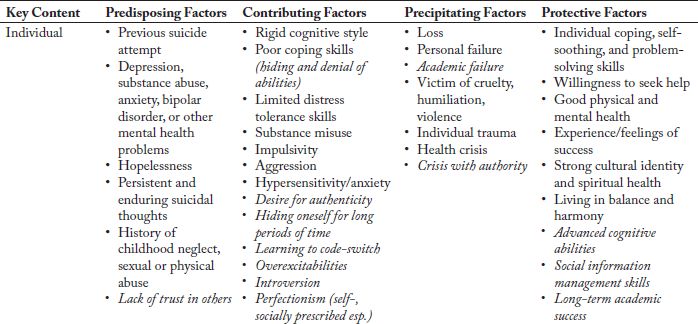

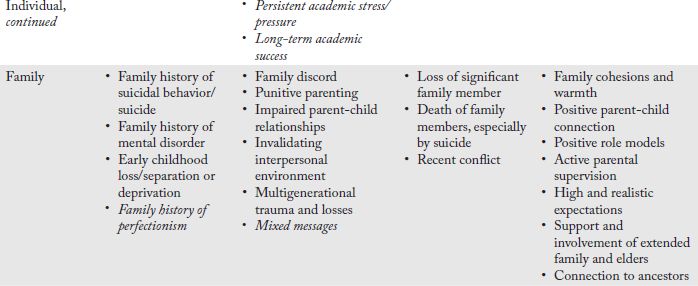

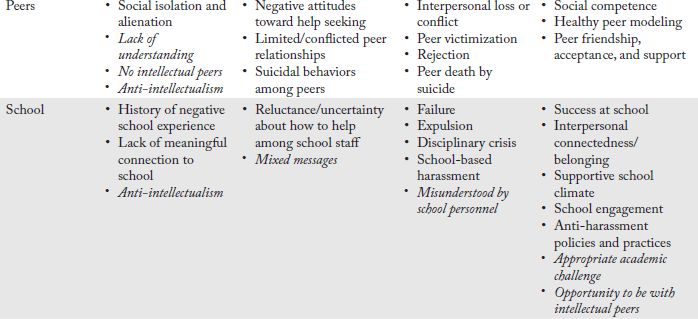

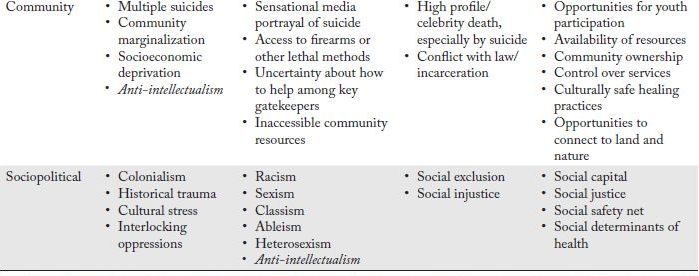

An excellent visual illustrating factors that both make people vulnerable to, and protected from, completed suicides is included in Table 10 (adapted from White, 2016), a quick guide for adults who want to familiarize themselves with predisposing, contributing, precipitating, and protective factors by key content as broken down into the categories of individual, family, peer, school, and community. Individuals may be predisposed to considering suicide due to their prior experience, family history, or events in their community. The influence of these predispositions may be multiplied by contributing factors at every level. Events or circumstances can become precipitating factors that make suicidal thinking more likely. These factors can be tempered by protective factors such as those listed. We have added items to White’s original table that are specific to students with gifts and talents. Table 10 provides the reader with information about ways that people are naturally protected from engaging in suicidal behavior and some ways to provide these protections. The big picture represents an optimistic and somewhat thorough overview of factors associated with suicidal behavior.

One can easily imagine a person grappling with some of the factors while benefitting from others. However, the degree of influence across the factors varies widely and some have not been empirically validated in a list like Gould et al.’s (2003) have been. However, once again, there is considerable overlap with other, more scientific lists. The gestalt of Table 10 is that it is more phenomenological than merely listing factors. Many of the terms and phrases in Table 10, such as humiliation, are powerful examples of human experience that can be quite motivating when combined with other factors, such as feeling trapped or hopeless. In essence, a person can become increasingly weighted down as the number and/or severity of the suicidal factors impacts him or her. This description of a phenomenological model of suicidal behavior is the image that we are moving the reader toward—away from a conception that is more associative or based on a list of factors.

Table 10 includes risk and protective factors from several perspectives, including the community. This particular perspective is usually outside the emphasis of any book that is more school-focused. It is included in this book, however, because schools are often situated within communities. Communities are also where media portrayals of suicide events of myriad famous people, such as the musician Chris Cornell or actor/comedian Robin Williams occur. It also supports the earliest contention of this book—that to understand suicides, one must understand the context in which they occur.

KEY POINTS

Suicide risk factors have been defined in order to predict completed suicides by correlating traits, qualities, and behaviors with completed or attempted suicides.

Suicide risk factors have been defined in order to predict completed suicides by correlating traits, qualities, and behaviors with completed or attempted suicides.

Two theories important for understanding suicidal behaviors are psychache (Shneidman, 1993) and the suicide trajectory model (Stillion & McDowell, 1996).

Two theories important for understanding suicidal behaviors are psychache (Shneidman, 1993) and the suicide trajectory model (Stillion & McDowell, 1996).

Significant risk factors for adolescent suicide, as defined by Gould et al. (2003), include psychiatric disorders, substance abuse, and cognitive and personality factors.

Significant risk factors for adolescent suicide, as defined by Gould et al. (2003), include psychiatric disorders, substance abuse, and cognitive and personality factors.

Sexual orientation becomes a risk factor depending upon the lived experience of a person or his or her treatment in society.

Sexual orientation becomes a risk factor depending upon the lived experience of a person or his or her treatment in society.

Another risk factor is glamorization of suicide through media coverage (e.g., celebrity suicide).

Another risk factor is glamorization of suicide through media coverage (e.g., celebrity suicide).

The access to lethal methods (e.g., firearms) risk factor is important because it increases chances of a successful suicide.

The access to lethal methods (e.g., firearms) risk factor is important because it increases chances of a successful suicide.

Knowledge of risk factors benefits our understanding and potential to intervene in positive ways to help prevent completed suicides.

Knowledge of risk factors benefits our understanding and potential to intervene in positive ways to help prevent completed suicides.

Table 9, featuring information offered by the American Association of Suicidology, is a comprehensive way to remember consensus of warning signs of suicide (IS PATH WARM?).

Table 9, featuring information offered by the American Association of Suicidology, is a comprehensive way to remember consensus of warning signs of suicide (IS PATH WARM?).

The suicide risk and protective factors table (Table 10; White, 2016) provides a phenomenological model of suicidal behavior.

The suicide risk and protective factors table (Table 10; White, 2016) provides a phenomenological model of suicidal behavior.