Figure 3. Illustration of suicide theories and students with gifts and talents leading to spiral model.

CHAPTER 7

TOWARD A MODEL OF SUICIDAL BEHAVIOR FOR STUDENTS WITH GIFTS AND TALENTS

Over the years that Tracy has pondered the suicidal mind and behavior of students with gifts and talents, he has considered the traditional research about suicide of the general population. He has considered contextual and historical influences and, finally, the actual research on the suicide of students with gifts and talents. His research conducting psychological autopsies caused him to see developmental aspects of suicidal behavior and the need to investigate the essence of lived experience of the suicidal mind. Learning that Shneidman had come to a similar conclusion fairly late in his career, he gained the confidence to make these aspects foundational to a new model that applied to students with gifts and talents. Shneidman’s (1993) work was most compelling in its rich description of the primal experience of psychache.

This synthesis of information has led to the development of the spiral model of the suicidal mind of gifted children and adolescents. The model attempts to build on both Shneidman’s (1993) work and the STM by Stillion and McDowell (1996). Conceptually, combined with gifted-specific research and observations, these two theories provide a comprehensive foundation that has the benefits of both the empirically validated research reflecting the general population and the fine distinctions needed to anticipate and understand the suicidal mind of students with gifts and talents.

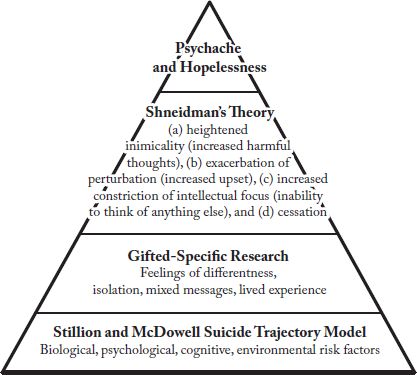

The spiral model of the suicidal mind of gifted children and adolescents will be described conceptually below and illustrated to assist with the explanations. It builds from the model categories and risk factors of the STM along with the more phenomenological aspects of Shneidman’s (1993) theory, to the more nuanced, empirically based ideas from the research on suicidal behavior of gifted students. For context, however, before presenting the spiral model, we will provide a two-dimensional illustration of a triangle (see Figure 3) based on the Stillion and McDowell (1996) and Shneidman (1993) theories, plus the research about gifted students and suicide. Subsequently, we present the spiral model, which attempts to provide a three-dimensional image of the interactions of all of the factors provided to date, including those specific to students who are gifted.

Figure 3. Illustration of suicide theories and students with gifts and talents leading to spiral model.

The bottom fourth of the triangle includes the four categories of the suicide trajectory model (see Table 11, p. 34, for a reminder of what those categories entail). The correlates and risk factors of suicidal behavior establish the foundation of the suicidal mind. However, many people function well, even with many of the suicidal correlates.

The STM establishes an excellent foundation of risk factors from which to look for and predict suicidal behavior. The four categories are comprehensive, including biological traits/characteristics (e.g., being male), psychological characteristics (e.g., mood states), negative cognitive patterns (e.g., self-talk), and environmental factors (e.g., social isolation and exposure to lethal weapons). These factors are at a level that educators could be trained to identify as a means to reduce the likelihood of suicidal behavior.

The next level of the triangle includes factors identified from research on the suicidal behavior of students with gifts and talents. Isolation, feeling different, lived experience, mixed messages, and others are layered on top of the factors of the STM.

The third tier of the triangle includes the elements within Shneidman’s (1993) theory. He described suicide as having four elements: (a) heightened inimicality, (b) exacerbation of perturbation, (c) increased constriction of intellectual focus, and (d) cessation. From the STM, we can now see how the process of the suicidal mind is becoming actively involved. As suicidal ideators increase their harmful thoughts and become more and more upset, they become less able to think about anything else. The only discernable solution is cessation: death. Factors associated with suicide can be considered kinetic, and Shneidman’s theory illustrated how the factors become activated or engaged.

As the person becomes increasingly involved in suicidal ideation, the factors noted in the STM, such as rigidity of thought, exacerbate the perturbation (increase the upset) that Shneidman (1993) described. This is where the two most important states can have the effect of preparing the person to die: psychache and hopelessness. As a person experiences increasing amounts of psychological and emotional pain, the variable of hopelessness becomes more and more important.

Risk factors can be considered distally related to suicide, while warning signs such as psychache and hopelessness are thought to be proximally associated with a suicidal behavior and related to imminent risk. Distal causes are believed to be the initial causative factors in the original environment, while proximal causes are current causative factors.

These proximal causes can be seen at the top of the triangle, in Shneidman’s (1993) psychache and the construct of hopelessness. The two states of mind are much closer to potential suicidal behavior than any of the correlates. However, the correlates provide fuel for the psychache that leads to hopelessness, which in turn leads to suicidal behavior.

SPIRAL MODEL OF THE SUICIDAL MIND OF GIFTED CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS

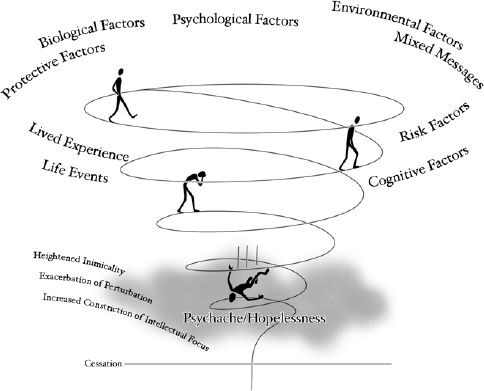

Building on the theories and research represented in the triangle in Figure 3, Tracy developed the spiral model of the suicidal mind of gifted children and adolescents, shown in Figure 4. The image of the spiral was chosen as a good metaphor for a person’s life and how differing events, circumstances, and protective factors battle to keep a person spiraling high above the destruction on the ground before one crashes through and dies. The image allows for important details to be shown as weights or protective factors.

Figure 4. Spiral model of the suicidal mind of gifted children and adolescents.

The swirling around at the top of the spiral illustrates the movement in one’s life in a relatively flat plane of positive mental health. This is where most people operate on a day-to-day basis, when their lives are in a positive state. An individual’s path dips with events and circumstances in life that cause high levels of upset, anxiety, or distress, but remains in a generally positive trajectory along the top. Negative effects on the mental health plane of the top spiral tend to be episodic for most people. Those people with bipolar disorder, for example, experience extreme emotional swings, and would reflect that in their image of the spiral, with many dips along the top plane. Others’ patterns, while idiosyncratic, would tend to reflect a relatively consistent plane, indicating the ability to deal effectively with life’s struggles.

Just as a tornado moves, a person is moving, developing over time. The height of the spiral is meant to reflect the distance one is from suicide, or, stated differently, a person’s level of mental well-being. The width of the body of the spiral reveals the speed of life as one experiences it.

A way to imagine this is to assume that this model of mental health represents the life of a person across his or her lifespan. For some, the spiral lasts 85 years or more, while others die at birth. For those who survive birth, many of the protective factors are present, such as good health, positive parent-child relationship, and so forth. The image of a newborn actually illustrates the early indicators of the importance of relationships with others to the mental health of a person as he or she grows into adulthood. More specifically, if the child is not fed, then he or she dies. If he or she is not changed regularly or is neglected, then he or she fails to resolve a psychosocial crisis and develops doubt about how much trust can be placed in others (Erikson, 1963)—a doubt that is carried through life. As the young person develops, increasing numbers and types of protective factors are also developing. For example, love for family and friends, a sense of identity, development of agency, belief in one’s competence, and many more are added to the biological predispositions that help keep a person safe. Belief systems that make suicide taboo can also be helpful in keeping people alive.

In sum, the spiral serves as a reasonable vehicle on which to place the numerous biological, psychological, cognitive, and environmental risk factors of Stillion and McDowell’s (1996) theory. The same is true for Shneidman’s (1993) psychological constructs of heightened inimicality, exacerbation of perturbation, increased constriction of intellectual focus, and cessation. Combined, these two theories establish a solid foundation to which we can add the gifted-specific issues, concerns, and phenomenological factors. In addition, Table 10 (see p. 27) provides a representation of both the factors associated with suicidal behavior and protections against it. If you consider it the backdrop for the spiral, it is easy to imagine how the person can be influenced over time.

The problem emerges when a person gets knocked out of his or her spiral that is parallel to the ground. Stillion and McDowell (1996) noted myriad life events that can cause this, such as divorce, moving, illness, death of family members, and relationship problems. Table 10 also includes some of the precipitating factors that can contribute to the drop off the top plane. In most cases, the protective factors such as those in Table 10 illustrate why we tend to bounce back, regaining our symmetrical orbit, parallel to and above the ground. Drugs and alcohol, depression, or other comorbid psychological issues are examples of factors associated with suicidal behavior. These can be seen in Stillion and McDowell’s (1996) and Gould et al.’s (2003) work. As illustrative as these correlates and risk factors are, it takes hopelessness and Shneidman’s (1993) psychache to break through the protective factors that keep us safe from suicide. The intense psychological pain and hopelessness make a person most susceptible to efforts at eliminating the overwhelming, inescapable pain. Suicide attempts are most likely to occur at this point.

The spiral, with the issues and factors from research on students with gifts and talents, provides a visual aid in understanding the suicidal mind of the child or adolescent. For example, we have learned that the factor structure of suicidal ideation among gifted adolescents is different from that of their nongifted peers (Cassady & Cross, 2006) and that gifted adolescents reveal some personality types (introversion and perceptive) that are more closely associated with suicidal ideation than the general population (Cross et al., 2006; Cross, Cross, Mammadov et al., 2017). Although these two examples are important, the research needs to be replicated with expanded samples of students with gifts and talents.

Research on the personal experience of giftedness suggests that gifted and talented students receive mixed messages abut their giftedness (Coleman & Cross, 1988), often grow up in anti-intellectual environments (Howley et al., 2017), believe that they are different from others (Cross et al., 1993), perceive a stigma of giftedness (Coleman, 1985), and engage in social coping behaviors (Coleman & Cross, 1988; Cross & Swiatek, 2009) to create a level of comfort within their schools. The internalization of these influences on the identity of gifted students adds to their negative self-images, inducing a lack of confidence and self-doubt. Moreover, the simple fact is that extraordinary minds have few peers. Combined, these factors can lead to anxiety, isolation, alienation, and depression—correlates of suicidal behavior. In the spiral model of suicidal behavior, we can see how the weight of negative correlates can hasten the downward progress toward a desire to end one’s life and, then, to cessation. This progress may be halted and even reversed, when we bolster protective factors and attend to the contributing factors and predispositions through such practices as counseling, social work, or active engagement.

KEY POINTS

The spiral model of the suicidal mind of gifted students builds from the model categories and risk factors of the Suicide Trajectory Model (STM) to the more phenomenological aspects of Shneidman’s (1993) theory, to the more nuanced, empirically based ideas from the research on suicidal behavior of students with gifts and talents.

The spiral model of the suicidal mind of gifted students builds from the model categories and risk factors of the Suicide Trajectory Model (STM) to the more phenomenological aspects of Shneidman’s (1993) theory, to the more nuanced, empirically based ideas from the research on suicidal behavior of students with gifts and talents.

The factors of the STM are generally at a conceptual level that professional educators could be trained to identify, and in many cases work with, to reduce the likelihood of suicidal behavior.

The factors of the STM are generally at a conceptual level that professional educators could be trained to identify, and in many cases work with, to reduce the likelihood of suicidal behavior.

The next level of the spiral model is Shneidman’s (1993) theory, illustrating how the factors associated with suicide become activated or engaged.

The next level of the spiral model is Shneidman’s (1993) theory, illustrating how the factors associated with suicide become activated or engaged.

Risk factors can be considered distally related to suicide, while warning signs such as psychache and hopelessness are thought to be proximally associated with suicidal behavior and related to potential imminent risk.

Risk factors can be considered distally related to suicide, while warning signs such as psychache and hopelessness are thought to be proximally associated with suicidal behavior and related to potential imminent risk.

The weight of accumulated risk factors can make descent through the spiral faster. Protective factors enable up-ward movement and lend stability to an individual.

The weight of accumulated risk factors can make descent through the spiral faster. Protective factors enable up-ward movement and lend stability to an individual.