Taller, I walk through the shrunken corridors

On the cross of whose walls I was nailed

My gelatinous mind impaled

My gelatinous heart jelled1

BY AGE TWELVE, I was brainy. Teachers liked me. Miss Eldred in the fourth grade was the first to dote on me and to tell me that I was unusually bright. Beth and my parents said so, but Miss Eldred was more credible, since she penciled my report card and therefore was harder to discount. I was fast and confident in class—if not on the street or the Little League diamond—and liked to show off my smarts. I had my hand in the air before almost all my classmates—except Gary Hoke, who mercifully decamped to Cleveland midyear. Facts stuck to me, and learning was effortless. When it did demand effort—like plowing through a whole book—I didn’t do it. I bluffed my way through the long stuff.

I strongly identified as Jewish. You (and I) should find this noteworthy, even provocative, given the dark stories I’ve just narrated and the absence of any positive memories that come to mind. But tribalism is surely not about the good times, and it penetrated to my soul. When I scanned the front page of the Knickerbocker News, as I did every evening after reading Alley Oop, the J-word just popped off the page. I was part of a minority and a persecuted one at that. It was dangerous to be Jewish. They might descend on us in the middle of the night and cart us off to the gas chambers. I was chicken-shit Jewish, not proud Jewish like my Hebrew school teachers. Most of our neighbors were Catholic, and they were also tribal. But they were not hostile, and we were tolerated, at least to our faces. I was never called a dirty Jew, but this did not weaken my lurking paranoia. At Christmas, Easter, and especially on Sunday, the difference between the Seligmans and the Campbells and Buccis was stark. My parents almost never socialized with the goyim, and unlike our Reform Jewish friends, we didn’t have a Hanukkah bush.

Lastly, I was déclassé. I was soon to find out what this meant.

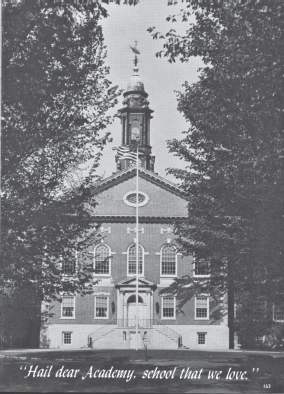

MY FATHER DROPPED me off at the bottom of the circular, elm-lined driveway of a stately Georgian edifice surrounded by a greensward of tennis courts and football fields. I was not allowed to walk up the white marble steps and go in by the front door. Rather I was ushered around the side and into the “buttery,” a cavernous, low-ceilinged, wood-paneled affair. I sat on one of the long benches set at a gleaming hardwood table. There were about fifty boys of my age so seated, and on the hour we were each presented with a booklet, a pencil, and blank answer sheet. This was the entrance competition for admission to the Albany Academy for Boys. It was (I now know) just an IQ test. No need to bluff here. I breezed through it and finished minutes before any other boy.

Weeks later my parents told me that I would be attending the academy in the fall of 1955 for second form (the British public school term for eighth grade). My father was very proud. He and Irene had decided to make a big sacrifice for my future. Adrian, as deputy state reporter of the Court of Appeals, earned less than $7,500 before taxes, and the tuition they shouldered was $600 plus uniforms, lunches, bussing, and fees.

Why this sacrifice? Not only did the teachers at School 16 not teach anything, but college admissions officers had sniffed this out. Even the valedictorian from Albany High School must have struggled to get into Cornell—the zenith of aspiration for students of the Albany public schools. Harvard, Yale, and Princeton were out of reach. Beth had been admitted to Radcliffe, but my parents would not pay for a girl to be so expensively educated. So she went to the University of Rochester for just one year and then to the free New York State Teacher’s College in Albany. The best graduates of the Albany Academy for Boys, however, sometimes got into the great universities, and my assigned role was to burst the chains that had shackled the family since Marten’s rejection by the Viennese Academy of Fine Arts, Big Brother Bert’s Millions, the Great Depression, and the gray civil service.

I was told none of this of course, not even about Radcliffe.

IT IS 1998. Darryl, my son, is four years old. I am fifty-four years old. My wife Mandy and I tell Darryl that he has to have exploratory surgery, a colonic biopsy. He is scared and bewildered. He goes out the kitchen door and sits on a low wall. Over and over he drops polished stones one at a time into his hand, empties his hand, and does it again. And again. After an hour he comes back in.

“I’m ready,” he says, and lightning arcs across the generations.

IT WAS THE last day of August 1955. I was scared and bewildered. I would be bussed to a new school, a military school, all boys, uniforms, a battalion, rich kids, and only male teachers. I didn’t know a single person. I would be kept there every day until 5 p.m. My bar mitzvah was in two months. My very body was erupting: a four-inch black hair had sprouted in my groin. In the gray drizzle, I took foul shots over and over for two hours. With every clunk of the basketball against the backboard, the haze of childhood dropped away.

“I am ready,” I said out loud.

I TOOK THE same walk as before, but now I stopped at the corner of Madison and Allen and waited for the school bus. I was in uniform, my black knit sweater tucked neatly into the heavy gray woolen trousers. An older boy in uniform waited on the corner.

“Hi, I’m Jerry Spector,” he said, “and your sweater is on wrong. It isn’t supposed to be tucked in.” Blushing self-consciously, I pulled my sweater out of my trousers. Before the bus could arrive, a huge, befinned Cadillac pulled over, and we were offered a ride. Jerry got in. Sheepishly I slinked in behind him. The driver was Mr. Titus, and his son, David, in the front seat, was, like Jerry, a fourth former.

The Albany Academy for Boys. In the spring of 1955 my father dropped me off at the bottom of the circular, elm-lined driveway of a stately Georgian edifice. Here are the stairs I was not allowed to walk up until my senior year. Photo from Cue, 1960 yearbook.

As we alighted in the circular driveway, Jerry whispered to me, “Wow. Their older son was the major of battalion, the pinnacle position in the student body, last year. The major—John Abel Titus, and Mr. Titus is ‘Mr. Major-maker.’” Jerry said this reverently.

“WHAT IS THE story of the Hayes-Tilden election of 1876?” Mr. Steck asked in a sharp midwestern twang. It was second-form American history, a continuation of first-form American history, which must have left off with Ulysses Grant. My hand shot up. Puzzled, Mr. Steck called on me. I narrated the electoral vote tie and then the sellout to the southern forces in the House of Representatives. As I talked, Mr. Steck’s face got redder and redder. He cut me off at the word “Reconstruction.” I had answered a rhetorical question. I was told to stay after class and wrote “soybeans are better” one hundred times, covering three blackboards before he dismissed me.

The day ended on the football field. To my surprise I recognized the coach, Bob Olcott. Burly Bob had been the amiable swimming instructor at the Stratton Mountain Boy Scout camp the previous summer. He had failed me on my swimming merit badge for doing a scissors kick, rather than a frog kick, with my breast stroke. Duly corrected, I finally got the badge.

“Hello, Bob,” I said. His jaw dropped. There was a stunned silence from the football kids within hearing range.

“It is ‘Mr. Olcott,’ and it is ‘Sir,’” he said. Not a perfect start to my five years at the Albany Academy for Boys.

I made some friends in the first two weeks: red-headed Charlie Witherell, who sat noisily behind me in first-year Latin, whose older brother, Warren, was a renowned water-skier; and Charles Lansing Pruyn Townsend, star athlete who bounded like a mountain goat down the marble steps three at a time. The very same name was also up on the mahogany Class of 1927 plaque listing the majors for the last 140 years. In that case it was Charlie’s father’s name, and Charles senior was now the PMS&T, or professor of military science and tactics. I never discovered what that meant that he did.

One boy had been unaccountably absent for the first two weeks and was whispered about in tones of awe. He was a star student, a poet, and the fullback. His father, Sidney, owned swaths of downtown Albany and Troy. (A decade later William Kennedy would defame Sidney on the front page of the Times Union as a “slumlord.”)

Sight unseen, I was starstruck.

The young man finally appeared. He had been on a family vacation. Strikingly handsome, a shock of red-brown hair combed insouciantly over his left eye, more mature than his prepubescent classmates, and quietly aloof, he exuded mystery. If the second form could be said to have a god, it was Jeffrey Albert.

With more than a touch of hero worship, I focused on befriending Jeff. He and I had in common “pre-intellectualism,” a better trait than pseudo-intellectualism, but not much better. We asked profound questions (two years too soon to be sophomoric) about God, truth, meaning, and death, and we looked down on those boys who were not as profound. Jeff and I did not, however, have in common spending money, popularity, athleticism, tailored uniforms, good looks, and a gaggle of lovelorn second formers from the Albany Academy for Girls. Jeff had all of these.

Jeff lived in a mansion at the bottom of Marion Avenue, the place to live. My parents had walked me to that part of Albany on Sunday strolls, imagining the lives of the other half.

I was invited for dinner. The Alberts had a live-in maid—Eppsie— and she served us each a whole guinea hen with raisins. We sipped a French wine. Beatrice Albert presided. She was gaunt and deeply bronzed, her lustrous black hair was regally coiffed, and she spoke with a southern accent. She used words like “trepidation.” The conversation was about golf at the Colonie Country Club and the doings of the Barnets and the Sterns, the old Jewish families of Albany. I did not yet know the term “nouveau riche” or even have an inkling of the concept.

There were bowls of fresh fruit in the basement, a pool table, a ping-pong table, and a pinball machine. Beatrice, who unbeknownst to me had clawed her way up from southern poverty to marry the richest lawyer in Albany, immediately sensed my true social standing and almost by telepathy communicated it to me. I blushed violently and found myself saying “social climber” over and over to myself about myself.

IT IS A perfect spring day in late May 2013. Acres of tulips are out in Washington Park. It is the day of the two hundredth anniversary of the founding of the Albany Academy. I receive the distinguished alumni award and am invited to give a speech. The academy’s headmaster introduces me as its “most important graduate since Herman Melville.” Puffed up, I decide to take a memory jaunt around Albany. I walk three miles all the way to Jeffrey’s house. There is a new wing jutting from its west end. I stare up at the vast pile. I want to ring the doorbell and tell Mrs. Albert about Herman Melville and me.

I stand transfixed for a full minute. I tremble violently and then slink away. Beatrice Albert haunts me all the days of my life.

MY BAR MITZVAH was an unusual double event, with Gerry Shay and me having to share the spotlight. The Kibby Koblenz wing had wrested control of the synagogue from my father and vengefully slighted the son of the outgoing president of Temple Israel to deliver their message. Decades later my sister told me that Adrian’s name was not even on the plaque memorializing the past presidents of Temple Israel.

I was told none of this, but I could sense my father’s frustration and helplessness … and something even worse, something that felt like a boil about to burst.

The reception was a meeting of oil and water. Enthusiastic but clueless, I had invited my old friends from School 16 and from the Boy Scouts and my new friends from the Albany Academy: Jews and non-Jews, rich and poor, the old gentry and the newly arrived, the tailored and the shabby. The girls also came from all these strata. Except for the mysterious magnetism by which the pretty girls attracted an adventurous boy or two across the invisible boundary, the worlds didn’t mingle. They rarely jitterbugged together and never slow-danced together. It was an awkward afternoon and exposed for all the Academy boys and girls to see what Beatrice Albert instantly recognized: Martin did not belong.

My mother asked me that evening if I would be continuing my Jewish education. I emphatically told her that this was my last day in a synagogue and that I did not believe in God. Late that night I heard her sobbing softly in the next bedroom.

MY FATHER HAD arrived at a turning point in 1955. Young newlyweds of the Great Depression, he and Irene had chosen the safe life: civil service and a guarantee of lifetime employment. They watched in surprise as the economy boomed after World War II and into the 1950s. No depression returned. Their peers—whom they often called “dopes”—turned out not to be so dopey. Many of them were becoming really prosperous, leaving my family in the dust. At least the civil service promised advancement for talented lawyers, and my father was talented. Irene told me that he was fast, so fast that he could do in one hour what other lawyers took a full day to do, and so he had seven extra hours to make his work perfect. He was forty-nine years-old, and the next big job opened up: state reporter of the Court of Appeals. The job after that might even be justice of the Court of Appeals. Blue skies. Adrian was a shoo-in. No one else was nearly as talented.

Shortly after my bar mitzvah, he came home in the middle of the day, close to tears. He had not reckoned on Irish politics. James Flavin, a favorite of the O’Connell machine, was promoted over him. Just as he had as a child, Adrian went into hiding. He stayed home for weeks with a cold.

But he emerged from this dark night of helplessness with a big plan. He would run for office, and not just any office—for the second-highest office in New York State: comptroller. He was a natural politician. I had watched him work the beach in Lake Luzerne. He often approached strangers, asked them questions that he knew the answers to, and so got them talking about themselves. After fifteen minutes he had a new friend. He approached all these friends for campaign money and began to build a war chest. He angered easily now and was feverish with activity.

I HAD BEEN doing very well academically. An A was a rare grade at my school, and I was getting lots of them—even in Mr. Steck’s American history class. Mr. Santee, the second-form English teacher, was underwhelmed, however. He kept me after class for talking out loud without raising my hand and had me write a spontaneous one-page essay on John Buchan’s racist novel Prester John. I handed it in confidently after ten minutes—like my father, I was a fast worker. Mr. Santee was delighted: I had fallen into his trap. He warned expectantly, “Unless every i is dotted and every t is crossed, Seligman, you fail for the period.” Each i was dotted, and each t was crossed. Mr. Santee was visibly annoyed.

But I was not doing well socially. I manned up and asked Mary Ellen Fisher on a date to the movies. It seemed to go well, and her mother told my mother that I was a “perfect gentleman.” Mary Ellen threw a big party a month later for the whole “crowd,” the big social event of the fall. I was pointedly not invited. Except for what was soon to befall me, this was the worst thing I experienced in second form.

I was also not doing well with the boys. I loved food. Lunch in the buttery—white bread with browned chicken gravy—was a blissful break in the eight-to-five Academy day. When I am happy eating, I hum. It was a fiercely cold winter lunchtime. I was happily eating and noticed that the entire room had fallen silent. I looked around. Everyone was staring at me and listening to my humming. The older boys were beside themselves with laughter. I turned beet red. I wanted to die.

There was one other new boy in second form who shared my status: half Jewish, no money, brainy, not an athlete, nomadic, with a civil servant father. His name was Robert Kaiser. His father was an aide to the governor. Bob and I let down our guard with each other, and we spent weekends comfortably together. Governor Harriman, broomstick stiff and overly meticulous of speech, came to dinner at their house, and he was the first dignitary I ever met. Mr. Kaiser actually called him “Averill.”

The Kaisers had a drafty weather-beaten farmhouse in Guilderland with a large empty pasture. Bob and I scraped together fifty dollars and bought a green 1948 Ford. We were both just thirteen, but you did not need a license to drive on private property. We mowed an oval track into the pasture, and Bob’s mother showed us how to work the balky stick shift. She made us wear our football helmets. We spent heavenly afternoons racing at top speed around our little track. We went to the drag races on Saturday nights.

One perfect May Saturday, Adrian drove Bob and me in our family’s 1950 black Chevrolet to the golf course. As he departed, Adrian remarked casually that he couldn’t feel his left arm. I caught his nervous chuckle and worried all through the afternoon. But when he picked us up, after an afternoon of campaigning, he seemed fine.

He went to see Dr. Drapkin, the doctor around the corner. Adrian’s blood pressure was sky-high: 300/180! Dr. Drapkin dismissed him with the advice “Take it easy.” An effective antihypertensive drug, warfarin, had recently come on the market, but this life-saving knowledge had not yet made its way up the Hudson River to the general practitioners of Albany.

The next Friday I overnighted after school at Jeffrey’s house. I walked home in the morning, and as I rounded the corner of South Main and Madison Avenue, I saw flashing red lights in front of our house. I raced down the block to see my father being wheeled on a gurney into an ambulance. I could hear him speaking, but I couldn’t make out the words. It was apparently an attempt at humor since the paramedic feigned a laugh. They drove off at top speed, siren blaring.

Adrian had a stroke, a cerebral thrombosis. It was serious but not life threatening. I was afraid, actually petrified, to visit the hospital. I couldn’t bear to see him so struck down. His big brother, Bert, rushed up from Manhattan and visited for two hours. Irene heard a loud argument from inside the hospital room. Bert exploded out the door and left. Irene rushed in. Adrian was unconscious. He had suffered another stroke, this one massive and irreversible. We never found out what Adrian and Bert had argued about.

When Adrian woke, he was paralyzed on his left side and not expected to live. Against the odds, he survived and spent the next two weeks in Albany Hospital. Then he was transferred to a nursing home in Guilderland, where he spent the next two months without improvement. I finally steeled myself for a visit. I could see in a glance that he had lost twenty pounds, and his left arm and left leg were withered and motionless. He was overcome with tears when he saw me. His speech was unimpeded, and except for being more emotional than before, he seemed quite lucid.

At the end of the visit, he told us in a choking sob, “I don’t believe in God. The only thing I believe in is you—Irene, Martin, and Beth— and I don’t want to die.”

Adrian never recovered. By the end of the summer he was sent home, still paralyzed, still emotionally labile, and wholly drained of his hallmark vitality.

“HI THERE. SORRY to bother you, but I’ve been talking to all the folks here in Greenwich [pronounced ‘green witch,’ not to be confused with the posh suburb in Connecticut], making a sort of survey. I’m not here to sell you anything,” I lied.

Bob Kaiser had seen an ad in the Knickerbocker News from the Keystone Readers Service offering to hire boys as young as thirteen. We needed the money. Irene had called a family council. She told us that the nursing home costs had wiped out almost all our savings and all their insurance, and now Adrian would need round-the-clock nursing care when he came home. Beth all too eagerly suggested that I return to public school, saving almost $1,000, and Irene very reluctantly agreed. A year ago I would have burst into tears, but now I was a man, and the man of the house, so I quietly decided to go looking for a job with Bob.

Bob and I appeared for the interview on the fifth floor of a rundown office building in lower Albany. There was no interview. All the boys who showed up were hired on the spot. There was no salary, only a commission, four dollars on the thirty-six-dollar deal. Those few boys who didn’t quit the first week would be the summer sales force. We were door-to-door magazine salesmen. The customer got four three-year subscriptions to Curtis Publishing House magazines. Five boys were packed into each car and driven to hamlets all over upstate New York. We avoided rich places (residents were too smart not to realize that thirty-six dollars is no bargain, since they would pay exactly that if they wrote in for subscriptions), and we avoided poor places (where people didn’t have the two-dollar down payment). We met hundreds—and in my case thousands—of young housewives from poor working families.

“Would you mind telling me which three of these [I tried to hand her a laminated card with a list of magazines—Ladies Home Journal, Better Homes and Gardens, Field and Stream, Jack and Jill] are your favorites?” If she opened the screen door and took the card, I was halfway home. If she did not—saying, “Books! We don’t want any!”—I reassured her that I was not there to sell anything; I was just taking a sort of survey. Forty years later, New York’s state legislature would outlaw this as a deceptive sales practice, but in June 1956 it was legal.

Bob Kaiser quit in disgust after the first week. I, however, had made forty sales and was handed eight twenty-dollar bills, $160—more than my father, with a doctorate in jurisprudence, took home from the Court of Appeals. I did this for five summers, and by the time I was ready to graduate and had a driver’s license, I had my own crew of young boys. I made more money selling magazines than I would make again until I was an associate professor. When I was seventeen, Mr. Hunter, the owner, told each boy on the way out the door, “Touch the lucky stones.” Some of them obeyed reluctantly, but I recoiled at this mysterious sexual overture. He did not ask me again—but he did offer me the whole company in the summer of 1960 if I gave up my college dream.

When the Academy reopened in late September 1956, Headmaster Harry E. P. Meislahn called me into his office and told me that he was giving me a full scholarship. Beth and my friend Jerry Spector had been to see him to tell him I would have to withdraw because we were too poor. I had to wash dishes at lunchtime, but between that and my magazine sales, I was saved.

Henceforward, adopting my headmaster’s double middle initials, I would be Martin E. P. Seligman.

I was now a third former. I stood first in my class of fifty academically. But I was not brimming with confidence; quite the opposite: my father’s helplessness had affected me in ways I could not begin to fathom. I was ambitious to achieve the heights at the Academy, to become a major or at least a captain, and I was elected class president—the last presidency I would hold until I won that of the American Psychological Association. About eight of the third formers were promoted to private first-class—the very rich boys, Mr. Meislahn’s son, Findlay, and Charles Lansing Pruyn Townsend, the winner of competitive drill. I remained a private.

Bob Kaiser decamped for the Loomis School in Connecticut. His parents were in better touch with the real old-boy system than were the more provincial Albany parents. After Yale, Bob would be a journalist and historian, then famously the managing editor of the Washington Post under Ben Bradlee. He never had to sell another magazine. Dan Chirot took Bob’s place.

Dan was the most exotic kid in school. He was French, his blonde hair was wildly uncombed, and he spoke with just a trace of an accent. Despite being very middle-class—his father was an anesthesiologist in Troy—Dan was supercilious. Somehow, I felt honored when he deigned to chat with me. Even Beatrice Albert was taken in. When Dan and I arrived for dinner together at the Marion Avenue mansion, Mrs. Albert brightened visibly and hugged him. Mr. Albert asked Dan (who was just fourteen) to sip and then approve the red Bordeaux. “Quite potable,” he said.

I was chopped liver.

And Dan was superbright. The highest grade at the Academy was an A. Dan took French, and suddenly an A+ was publicly awarded. By the middle of fourth form, Dan did something no one else had ever done in the Academy’s 140 years: a headline in the Fish and Pumpkin announced that Daniel Chirot had gotten all A+s. I was being bettered, but not to be wholly outdone, I soon became the second boy to achieve this.

He joined Jeff and me as the class “intellectuals.” He was sophisticated. He read Le Monde and told us it had footnotes. He read Doctor Zhivago when it first came out. He talked about Napoleon’s exiles and about French socialism. Dan and I played chess every day, since we were excused from study hall because of our grades and, as nerds, didn’t play football. Dan read chess columns. I played a bold and un-lettered game. He usually beat me.

IT WAS THE first day of fourth form, and the battalion promotions were posted. I raced down the white marble steps to the basement bulletin board. Half the class would be promoted to corporal, the must-have next step on the way to leadership at the Academy. My promotion was a near certainty: president of the class and a close second in the class academically. I scanned the corporal list: Sangster … Siebert … Townsend … VanDerZee. No Seligman. Surely this was a mistake. It was not. I was promoted to private first-class on the list below. Dan Chirot remained a private … in his case proudly so. As for me, this was perhaps the most disappointing day of my life. I was heartbroken.

THIRTY-FIVE YEARS LATER, I attend an alumni event at the Union League in downtown Philadelphia. The speakers are Mr. Steck and Mr. Olcott, both legendary Academy coaches, both now almost eighty. I invite them to overnight at our spacious home on the Mainline, and both accept enthusiastically. The next morning, while Bob Olcott sleeps in, Ernie Steck and I have breakfast.

“You may have wondered, Marty,” begins Ernie, “why you were not promoted to corporal in the fourth form.”

Jeff Albert, Dan Chirot, and Martin Seligman. From Cue, 1960 yearbook. Photo courtesy of Ruth Andrus.

I am taken aback. How could he know about the trauma I have kept so secret? “Actually it really hurt and has baffled me all these years,” I confide to Ernie.

“You probably have no idea how anti-Semitic the Academy was in the 1950s. I arrived, as a newly minted teacher from Iowa, three years before you did. The Santees had us over to dinner, and Harold [who later became headmaster] asked me where I went to church. I told him I sometimes attended the Reform Synagogue. Harold left the table and did not reappear that evening. That is also, by the way, Marty, why you were rejected by Harvard.”

It had never—not even once—occurred to me that Mr. Steck was Jewish.

JEANNIE ALBRIGHT, Barbara Willis, and Sally Eckert were the it girls and the unattainable romantic interests of this chubby fourth former. What could I possibly do to interest spit-curled, ski-sloped-nosed Jeannie, or full-breasted Barbara, the voluptuous fount of pubescent gossip, or, most impossibly, winter-tanned Sally? Jeff, who had already cornered Jeannie, was almost every girl’s dream come true. Tony VanDerZee, though slow-witted, was from a family that had reigned in Albany for three centuries. Barbara already had her cap set at Charlie Townsend, or if that failed, at Tony as runner-up. Sally was the princess of the Catholic girls. She would marry the major of the battalion of the Class of 1959.

Jonathon Gordon—handsome, confident, and the likely major from our Class of 1960—it was rumored, had already gotten laid. How could I even get to first base? I could talk to them about their troubles. What a brilliant stroke! I was willing to bet no other guy ever listened to them ruminate about their insecurities, nightmares, and bleakest fantasies. I tried on the role, spending three hours a night on the phone listening to Sally or Jeannie or Barbara. I did not score or even come close, but I snuggled comfortably into my new niche—these were the baby steps to becoming the psychologist I would be.

In sixth form Mr. Charles Colton helped me take my first real steps. He had taught me Caesar in third form. One day I came in unprepared. When he called on me, I glided my way through a passage on Germania.

“You’re bluffing, Seligman,” he interrupted. “Zero.”

This was the only failing grade I ever got. I was never unprepared again, and except in poker, I never bluffed again. Not ever.

Three years later, Mr. Colton did me a momentous favor. He invented a new course called “The Humanities.” I had no idea what that was, but Jeff, Dan, and I and all the other cum laude boys took it. Paul Monaco was not one of the cum laude boys. He was the quiet, unassuming one. We shared a deep bond. His father, a daring star columnist for the Times Union, dropped dead at about the same time as Adrian had his strokes. Paul turned out to be the most loyal of my friends, and he, like me, had his life changed by his first encounter with the humanities.

We read Will Durant on religion and philosophy. We listened to Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. We read Dylan Thomas, lots of dark Dylan, as you can see from the poem at the beginning of this chapter. An unbounded new world opened. There was a life of the mind, and it was different from getting A+s and being a snobby intellectual. It was where I wanted to spend the rest of my life.

Graduation was a glum affair for me. Dan was valedictorian of our class—although fifty years later, my friend Doug North, valedictorian of 1958 and the new headmaster, sent me an official transcript stating that I had actually graduated first in the class. I did not receive the various academic prizes that I felt I had earned. Instead they were distributed to the boys whose families were most likely to support the Academy financially in future years. I felt more a failure than a triumphant graduate sallying forth to conquer new worlds. I was going to Princeton, and that should have been cause for celebration, but so were four of my classmates, and I was, after all, a Harvard reject. Beth and Irene hosted a lifeless party for me in the backyard with tables set up around our sour cherry tree. My cousins, aunts, and uncles were all there, but I was a zombie going through the motions. I did not belong to their underclass world any longer. My father was conspicuous, hobbled and unable to control his emotions, both positive and negative. He was proud. He had achieved what he sacrificed for, and I was no longer the poor Jewish boy I had been before the Academy.