“SNOW!” EXCLAIMED KERRY, looking out the second-floor bedroom window. We were scoping out Ithaca, guests in Jim Maas’s house in Brooktondale. It was late May 1967—hence the exclamation point. Indeed, a glaze of new-fallen snow covered Jim’s sloping lawn and his emerging crocuses. There was snow at the beginning and more snow at the end of our time at Cornell.

I had been offered two good jobs. One was at the University of Michigan, and at the end of my visit, I had a memorable and ominous conversation with Norman R. F. Maier. He was in the final year of a distinguished career and one of my heroes. His work bridged the animal laboratory and the clinic, and he had rediscovered “experimental neurosis” (Pavlov first named it1). Rats were taught to jump to the left window or the right window for food, but eventually the problem became unsolvable, and no window was consistently correct.2 The rats froze at the starting post and became vulnerable to auditory seizures produced by loud, high-pitched sounds. To my eye it looked like learned helplessness in the nontraumatic, positive case. I gushed at Professor Maier, and he blushed, seemingly quite unaccustomed to praise.

“Watch your back,” he warned me in hushed tones. “No one ever cites my work. My students can’t get jobs. You have embarked on a dangerous path. What you don’t know is that the academic establishment, those pure experimental psychologists, secretly despise our kind of work. I don’t know why, but my trying to apply experimental psychology to the clinic—as well as the existence of the entire profession of clinical psychology—embarrasses them, or worse.”

As Professor Maier was warning me, I flashed back to two recent puzzling incidents at Penn. In Dick Solomon’s Thursday lunch seminar, I mentioned Joe Wolpe’s work as a good example of straightforwardly applying basic behavioral principles to real-world troubles. Dick, who insouciantly applied laboratory findings to the real world in his teaching—but almost never in print—reacted with contempt for Joe. He did not explain the ground for his contempt, but its vehemence was patent and wholly out of keeping with Dick’s sunny, tolerant character.

And just the week before my visit to Michigan, I had my first and only long conversation with Bob Bush. Bob, you may recall, had led the Harvard young Turks when they exited en masse to Penn. He was a mathematician by training and famous for the rigorous statistical modeling of stimulus-response-reinforcement learning. His work inspired the new generation of aspiring mathematical psychologists. He became the first chairman of the remade Penn department in 1958 and left the chair to Henry Gleitman just as I arrived. I told Bob about our work on learned helplessness and how our tests demonstrated that animals must integrate two conditional probabilities. I emphasized that this pointed directly to cognition and not to stimulus-response learning.

He listened patiently and clearly got it. At the end of the hour, he said, “If you are right, Marty, I’ve wasted my life.” Not long thereafter, Bob Bush killed himself. He had a complicated personal life, and I have no direct information about why, but when I heard the news, I could not help wondering.

“Watch your back, Mr. Seligman,” Norman Maier concluded. “You don’t want to end up like me.”

Except for the awful weather, Cornell contrasted sharply with Michigan. Its homey department had only about twenty-five faculty members, completely dominated by one faction, the perception psychologists led by husband and wife team Jimmy and Jackie (Eleanor J.) Gibson. Jimmy was the brains and Jackie the enforcer. The Gibsons were the opposite of behaviorists in ideology, but they were just as cultish, tyrannical, and narrow-minded. They worked on the “affordances” that the environment lends to perception. The department had been hemorrhaging psychologists recently and was rebuilding. It made many job offers: the recipient most distinguished was Dick Neisser, who eagerly accepted. They tendered five assistant professorship offers, one to me.

Kerry cast the deciding vote between Michigan and Cornell. She had put her PhD ambitions on hold during our three years at Penn and wanted to get on with her career. Cornell has a good classics department, so we accepted Cornell’s offer.

WE RENTED A cozy sabbatical house on forty acres of woods on Ellis Hollow Road, east of campus, and finally I got a dog. Apollo, my blonde golden retriever puppy, and I spent hours exploring the woods and just sitting together outside in the cold, cuddling. My office was the fourth-floor attic of Morrill Hall, and my laboratory, Liddell Laboratory, a converted sheep barn, was about five miles away. My salary was $9,500, soon raised to an even $10,000 through the generosity of Harry Levin, the chairman. Harry assigned me to teach “Introduction to Experimental Psychology.”

On the first day, I took a seat in the middle of the lecture room and narcissistically relished the collective gasp when I came to the podium and the undergraduates found that their professor was not much older than they were. This was the first time I’d designed and taught my very own course, and I did not do it the usual way. I used no textbook, only original journal articles, and created my own tour of what I considered “hot” across the discipline. My love of psychology came across, and the students were enthralled. I chose the topics according to my enthusiasm for them, and my enthusiasm was contagious.

Unexpectedly, this kind of teaching turned out to be a lightning rod for my own creativity. As I lectured, I found myself knitting together an entire area of psychology whose texture had previously been invisible to me. Today it is known as “evolutionary psychology.” Fifty years ago it did not exist.

John Garcia, a maverick who worked on animal learning in a radiation lab, had published a two-page article that went almost unnoticed for two years.3 When I first read it—and it was so badly written that I had to read it three times—I felt the earth move, but until I taught about the article, I did not fully understand why.

As I recounted the history of behaviorism to my students, I began to see that it was a rock-bottom premise of learning theory that John Garcia had obliterated. When John B. Watson, the founder of behaviorism, famously wrote, “Give me a dozen healthy infants, well-formed, and my own specified world to bring them up in and I’ll guarantee to take any one at random and train him to become any type of specialist I might select—doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief, and, yes, even beggarman and thief, regardless of his talents, penchants, tendencies, abilities, vocations, and race of his ancestors,”4 the political and scientific appeal was electric. This justified the egalitarian social program that underpinned American democracy as well as the Bolshevik and French revolutions.

“Pavlov and Skinner,” I recounted to my undergraduates, “believed fervently in ‘equipotentiality,’ the idea that any stimulus that is paired in time with any other stimulus will produce learning."

“Hold on, Marty,” objected Susan Mineka, a sophomore who twenty-five years later became editor of the Journal of Abnormal Psychology. “It can’t be any old stimulus. The animal has to perceive it and respond to it.”5

“Of course, Sue. But the crucial point is that these are exactly the associations that David Hume and John Locke argued make up the experience that writes on the blank slate,” I continued, making a mental note to invite this very bright sophomore into my laboratory. “It is just this flexibility of the brain that with the right experience will make of any man or woman a genius, the president of the United States, or a bigoted ignoramus.”

I decided to ease into the complicated Garcia experiment with an anecdote that captured its essence, and this juxtaposition of anecdote and hard data later became the hallmark of my teaching and writing.

“Sauce béarnaise,” I told my class, “is an egg-thickened tarragon-flavored concoction that used to be my favorite sauce. A few months ago, my wife and I had a delicious meal of filet mignon with sauce béarnaise. About three hours later, I got sick to my stomach, so sick that Kerry had to take me to the emergency ward to get an injection to stop my vomiting. I now hate the taste of this sauce. Just thinking about it—right now—sets my teeth on edge.

“Strangely,” I continued, “filet mignon did not become aversive, nor did my wife, nor did Tristan and Isolde, the opera I was listening to right before throwing up. Only the sauce did. What’s going on?”

“It’s just Pavlovian conditioning, Marty,” said one of the students. “The taste was paired with throwing up. Now the taste makes you sick to your stomach.”

“Anything wrong with that?”

“Plenty,” piped up Jim Johnston, a member of Cornell’s elite, experimental six-year BA-PhD program. “First, Marty learned with just one trial, and conditioning takes more pairings than that. And there was a three-hour gap between the taste and throwing up. I’ll bet if Marty wired up your chair, played a tone, and three hours later shocked your butt, you would not become afraid of the tone. Second, Tristan and the beef didn’t become nauseating even though they were just as well-paired with vomiting. The toilet seat was even closer in time to vomiting, and do toilet seats now make Marty sick?”

Wow, I thought to myself, Jim is amazing. He spoke in full paragraphs with no “uhs” or “likes.” Jim would go on within a decade to become one of America’s leading young cognitive scientists.

“Let me tell you all about the Garcia ‘double-dissociation’ experiment,” I continued. “Garcia works in a radiation lab and he gives X-rays to rats, which makes them sick to their stomachs. A few seconds before receiving the X-ray, the rats drink saccharin-tasting water, and with each lick they hear a loud tone. Good old Pavlovian condition, right? Both the sweet taste and the tone are paired with sickness. Later Garcia finds that the rats now hate sweet tastes but are completely unperturbed by the tone.

“Maybe the rats just didn’t notice the tone. So Garcia now does the same experiment, but with shock to the feet as the bad event rather than radiation sickness: loud tone plus sweet taste are both paired with foot shock. Now the rats come to fear the tone, but they still love sweet tastes! So they could perceive the tone after all. What is learned selects the ‘right’ conditional stimulus, depending on what kind of noxious event follows. Stomach illness selects for tastes and ignores the tone. Foot shock selects the tone and ignores the taste.

“Why?” I asked. The class looked puzzled. “What would Darwin have said about Garcia?”

As I thought over my education, nothing stood out as more egregious than third-form biology at the Albany Academy a decade earlier. F. Norton (Skippy) Curtis marched us through species, genus, phylum, and kingdom but omitted one thing: natural selection. I suppose he can be forgiven since it had been only a century since the publication of On the Origin of Species and the news may have traveled slowly up the Hudson River to Albany. We had pop quizzes, the most memorable question being “Name the authors of your textbook.” None of the forty-seven of us third formers got that one right (Moon, Mann, and Otto), but the name Mr. Curtis never mentioned was Charles Darwin.

When I first heard the principles of evolution from Colin Pittendrigh in my introductory biology course at Princeton (Pittendrigh’s own textbook), I lived through a thunderbolt of just the sort that must have shaken the fellows of the Royal Society in 1859. Natural selection reframes almost everything, and it has pervaded my thinking about psychology since. But like Skippy Curtis’s students, learning theory also missed out on evolution. How else could equipotentiality have remained a first principle?

Could learning itself be just as subject to evolution as the makeup of the eye and the ear? In the reality of mammalian evolution, distinctive tastes herald poisonous stomach illness, but sounds do not. Animals that could ignore external stimuli but selectively learn that tastes go together with illness—even with just one experience—would avoid those tastes in the future, survive, and pass on the genes that allowed such selection. Animals that could selectively associate sounds with pain and ignore co-occurring tastes would have a similar survival edge.

“Consider the evolutionary basis of learning itself,” I told my class. “Learning that mirrors the actual causal skein of the world will be favored and selected. Evolution may have prepared us to associate tastes with illness even over a several-hour gap. Evolution may have contra-prepared us to associate external events, like sounds, with stomach illness.”

My two teaching assistants, Meredith West and Drew King, chimed in. They had been studying birds over in the biology department. “It’s not just mammals that learn so selectively. Birds learn to sing in just the same way. They selectively imitate the songs of their parents and not the songs of bypassing strangers. And human language is like this too. This is at the heart of Chomsky’s theory that language is a species-specific human adaptation. Babies show ‘babbling drift,’ the accent of their babbling drifting in the direction of their parent’s language.”

Drew and Meredith were already an item and they went on to become world-class avian ethologists together.

Out of this course a Psychological Review article and my very first book, The Biological Boundaries of Learning,6 written with my graduate student Joanne Hager, emerged, as did a snide comment from the behaviorists calling my sauce béarnaise story the “most publicized meal since the Last Supper.” Most importantly, I joined the battle against the “blank slate” brand of psychology that ignores natural selection and insists that while having a brain is nice, that brain is just a means of faithfully transcribing what experience writes.

CORNELL NOT ONLY stimulated my creative juices but became a political hotbed as well. I got my first taste when I volunteered to serve on the undergraduate admissions committee. This was huge fun, particularly for me, since I liked spotting brilliant prodigies, such as stars like Jim Johnston and Sue Mineka, for admission into the six-year BA-PhD experiment. Toward this end, each faculty admission committee member got wild cards—applicants we could admit based on just our lone vote—if we agreed to mentor them through Cornell.

But President James Perkins played a wilder card than any faculty member had.

The issue was black admissions. The Black Student Association was agitating loudly for more black students, and we were very sympathetic—this in the first blush of enthusiasm for Lyndon Johnson’s vision of affirmative action. We had been bending over backward to take more and more black applicants. We reached deep into a small pool—students that all the Ivies were competing fiercely for—and we were hopeful that lots of academic talent might lie hidden beneath low Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) scores and low grades, particularly when the kid came from a poor neighborhood and a fatherless family. So we took lots of chances, admitting kids who showed glimmers of promise, particularly high determination in overcoming obstacles, even if they had mediocre high school grades and low SATs.

But we still were not keeping pace with the administration’s quota for black students, and an order came down from President Perkins. We didn’t hear from on high often, and the only other communication we’d had from him had been a cause for hilarity: I was going through a folder of a potential freshman from the Bronx and stuck upside down in it was a letter on the president’s stationery to the head of Knight Newspapers as well as the original letter to which it was a response. The Knight person endorsed a woman applying for the PhD program (this had nothing to do with undergraduate admissions), and President Perkins’s letter reassured him that his letter would “not get lost in the shuffle.”

The present order was not a cause for hilarity, and it would not get lost in the shuffle. We were instructed to take 100 percent of black applicants whose SATs averaged 600 or better. The SAT is a barely concealed and more publicly acceptable surrogate for the IQ test, correlating almost perfectly with IQ scores. An average of 600 was near the seventieth percentile for all college-bound applicants across America, and we were pretty much already admitting all black applicants in this range. No problem. We were further instructed to take 60 percent of all black applicants whose SATs averaged 500 or better, somewhat below the fiftieth percentile for all applicants. This was a push, but we guessed we could comply. And then came the wildest card in the pack.

We were instructed to take 40 percent of all black applicants with an SAT average of 400 or better. This was the bottom 25 percent of the entire American pool. (Do you see the problem before you read on?)

“Hold on,” said my fellow faculty committee member Thomas Sowell. Tom was a sober black economist who later became famous for his courageous take on the miseducation of young black kids.7 He pointed out a gaping statistical anomaly to us.

“Think about the bottom 40 percent of the pool of kids who average 500, the half we are instructed to reject. Such a kid might score 530 on average. What we are now told to do is to discriminate against this kid in favor of kids who score in the upper 40 percent over 400, say 460 on average. We are told to favor less talented (460) black kids over a large number of more talented (530) black kids. President Perkins’s theory seems to be that the lower the IQ, the more deprived and deserving the applicant is.”

“I quit,” Tom said, and he did. He left both the admissions committee and Cornell, but the admissions committee and Cornell continued to knuckle under. This foreshadowed the racial politics soon to come.

“HOW CAN YOU possibly claim that there are more than 10,000 advanced technical civilizations in the galaxy?” I challenged the brash, confident, and outspoken new arrival at the astronomy department. We were at a welcome dinner given by Bob and Jennifer Schneider. Bob taught calculus, and Jenny was jaw-droppingly beautiful—so beautiful that in Bertolt Brecht’s The Good Woman of Szechuan, she played the daughter, and at the serious line “Am I pretty, Mother?” the audience actually broke into gales of laughter. The new arrival had left the astronomy department at Harvard bitterly, denied tenure, and was holding forth unstoppably about intelligent life. He was strikingly handsome, gifted with a deep, mellifluous voice, and spoke in cogent full paragraphs. His name was Carl Sagan.

“I just wrote a long book about how widespread intelligent life must be with the Russian astronomer Shklovskii, Marty,” he replied handing me a copy. “Read it.”

And I did. I stayed up for the next twenty-four hours digesting his argument. The book culminated in a “qualitative equation” (I had not heard this term before), the Drake Equation, named after Frank Drake, a senior member of our astronomy department. On the left-hand side was “the number of advanced technical civilizations in this galaxy,” meaning civilizations that used radio waves for communication. On the right-hand side were the estimates for more than ten parameters to be multiplied together, such as the number of Sol-like stars in the galaxy, the percentage of those with planets, the percentage of those with planets far enough away from the star to be temperate, the percentage of those with atmospheres, and the longevity of an intelligent civilization (which was bimodal, either short and destroying itself right away or wise and long). The solution blew my mind: there are, right now, between 10,000 and 2 million advanced technical civilizations just in our galaxy.

Carl Sagan arrived at Cornell in 1968, rejected for tenure in astronomy at Harvard. We became fast friends. Carl embodied the responsibility of science to communicate effectively with the public, even at the cost of professional jealousy. Photo courtesy of Getty Images.

Understanding the human mind and the search for intelligent life in the universe were for me the two grandest of scientific pursuits. I chose the former for my life’s work because my mathematical skills for astronomy were not good enough. In Sagan, I met someone respectable who had chosen the latter.

We became fast friends and began to spend huge swaths of time together. We read each other’s manuscripts. He gave me an early draft of his Dragons of Eden, a book about the brain. The psychology in it was too sloppy, and I advised him not to publish it. It won the Pulitzer Prize. We swapped books that we read overnight and then discussed over breakfast.

“Read this one, Carl,” I insisted. “It might change your mind about truth.” I handed him the latest rage in the philosophy of science, Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.8 Kuhn argued that science was more about fashion than about absolute truth. He contended that in any current science, a “paradigm” dictated the right questions and created a hegemony of silence about those that should not be asked. The old guys died off, and the new guys then came along and swept away the old paradigm, replacing it with their own new paradigm. This sure looked right to me for psychology. Behaviorism swept away introspection, and now cognition was sweeping away behaviorism. Kuhn had created a sensation, and it fit the relativism that was just starting to overtake the humanities, as English and history departments started to switch from Shakespeare and Columbus to a focus on race, class, and gender.

The next morning over very strong coffee at Carl and his wife Linda’s apartment, Carl told me, “This is about bad science, Marty. Good science makes absolute predictions that can be proved or disproved. Good science is about the truth, not about fads. There are two theories about the origin of our solar system. One predicts that the moon is covered with a deep layer of dust. The other predicts that the moon’s surface is solid. Next year we will find out for sure.”

We watched the moon landing together at the faculty club. Neil Armstrong did not sink into a layer of dust.

“That’s good science,” Carl said with finality.

Carl had saved a book to read aloud to me for a very special occasion. Kerry and I were expecting our first child. Kerry went into labor, and I started our Buick and pointed it toward the Tompkins County Hospital eight miles away. Mindlessly, I then just let it idle in the driveway for six hours, and the car ran out of gas. Carl came to the rescue with a can of gas. After another twelve hours, the four of us raced off to the hospital, where Linda held my hand, and Carl read from J. B. S. Haldane’s essays on science. Amanda Seligman was safely delivered in the wee hours of a spring morning in 1969.

CARL AND I experienced together the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, the exit of Lyndon Johnson from the presidency, and the black revolution at Cornell. We both started out left of center and reacted to the same events in diametrically opposite ways. In the middle of all this, however, we had a personal rupture that was not about politics but about Carl’s physical health.

Carl had a ferocious temper and was easily offended. Kerry and I gave a dinner party in which Carl and L. Pearce Williams, a noted historian, faced off about the Boxer Rebellion. Williams sided with the imperialists and Carl with the Chinese. At first mention of the “yellow peril,” Carl stomped out, shaking his fist at Pearce. I had managed to stay on Carl’s good side up until then. Carl was going off to Boston for the first of the surgeries on his esophagus stemming from a rare cancer that would eventually kill him at the tragically young age of sixty-two. Kerry and I supplied Carl with our dozen favorite science fiction classics to read. Carl had never read any science fiction, saying that real science was much more interesting. But he agreed to read them during his recuperation and emerged from the hospital with the idea that became his novel, Contact.9

Linda called me from the hospital right after surgery and told me that Carl was in critical condition.

“You might give blood,” Linda suggested.

About six of our students and I drove to the donation center. I fainted while giving blood, and the doctor warned me never to do it again, but we did manage to donate a few pints. Within hours, Carl called me from his hospital bed. He was shouting, beside himself with fury.

“My illness was a secret. You betrayed me and told my students.” I’d had no clue. Carl recovered rapidly, but we would never be close again.

MY ACADEMIC WORK was going superwell. Steve Maier and I had found that learned helplessness was temporary: twenty-four hours after inescapable shock, the animals remained helpless, but if we waited a full week, the animals had recovered and escaped shock in the shuttle box easily. Then I found a condition under which learned helplessness was permanent. If animals had not just one but multiple sessions of inescapable shock, helplessness did not go away in time.10

Word of our work was spreading. I had been offered an assistant professorship at Harvard. My chairman, Harry Levin, mocked the offer: “Every Jewish boy wants to be at Harvard.” He hit the target and shamed me, and so I turned Harvard down. Steve Maier had taken a plum assistant professorship at Illinois. Princeton offered me an endowed bicentennial preceptorship, which came with an assistant mastership at my beloved Woodrow Wilson Society under Julian Jaynes, a former teacher. This dream offer from my alma mater was very tempting, but Dick Solomon told me to wait, saying many more offers would come my way. I turned Princeton down. (Many more offers did not come my way and never again from my beloved Princeton.)

I was initiated into the Psychological Round Table, a secret fraternity of haughty under-forty male experimental psychologists. It met once a year in a New York City mansion, and each member delivered a scholarly paper interlaced with humor. I was the youngest and least humorous initiate and worried that when they discovered my loyalty to applied psychology, I would be expelled. Dave Williams reported on Wilhelm Wundt: “Wundt was so disciplined that he wrote two thousand words every day for his entire career. Eighty-eight volumes in total. And in German. The last four volumes were all verbs.”

Tenure was all but certain at Cornell. My courses were oversubscribed. I had a large coterie of enthusiastic undergraduates working in my laboratory and a passel of sleepier graduate students. Senior professors from across the university invited me onto the right committees. They seemed to be grooming me for higher Cornell office. I had just received my first grant from the National Institute of Mental Health for research on learned helplessness.

“YOU REALLY DON’T know anything about clinical psychology, do you?” said Suzanne Bennett Johnson. Suzanne was a perky, freckle-faced senior and not at all intimidated. She got a rare A+ in my experimental psychology course, and I invited her into my laboratory, where she continued to shine. Cornell, being without a medical school, did not teach about mental illness, and I was now offering an advanced course on psychopathology—even though I was a novice. Suzanne was taking this course and saw my ignorance right away. She would become a clinical psychologist working on juvenile diabetes and was elected president of the American Psychological Association in 2012.

“You have us reading about learned helplessness and experimental neurosis in animals. Rats? Dogs? But what about people? What about schizophrenia, drug addiction, manic depression, and suicide?” chimed in Chris Risley, another senior not intimidated by me. (This “Marty” stuff had perhaps gone too far.)

On the first day of my experimental psychology course two years before, Chris, a wet-behind-the-ears sophomore, came bouncing into my office, beaming. “Hi, Marty. My name is Chris Risley. You should get to know me. I am really worth getting to know!” No undergraduate, before or since, has approached me in this bold way, and Chris turned out to be right. We became good friends, and he and Suzanne spent much of their time with Kerry and me at our house eight miles west of campus. Our house was now the watering hole for a dozen of my students.

When two of my best students, Suzanne and Chris, who were also now my close friends, told me that I didn’t know what I was talking about, I listened. They told me to get into the trenches and learn something about real mental illness.

I intended to take time off to learn clinical psychology, but such a profession barely existed. Psychiatry was the only profession that officially treated mental illness, and it was a guild that did not readily open its doors to people who were not medical doctors. Qualified psychologists were not welcomed and were allowed to enter only as handmaidens and supervisees of psychiatrists. Furthermore, I was not qualified to treat patients, and there was no well-charted trail for an experimental psychologist like me to follow to retool as a clinical psychologist. I was, however, about to have one blazed for me.

Suzanne B. Johnson was a sparkling Cornell undergraduate. She went on to become president of the American Psychological Association in 2012. Photo courtesy of Suzanne B. Johnson.

“CLINTON ROSSITER IS a racist and will die in the gutter like a dog. Allan Sindler is a racist and will die in the gutter like a dog. Walter Berns …” The litany went on, naming the faculty members who were to die. (I was not among them, being far too junior, obscure, and apolitical to be noticed by the leaders of the increasingly frenzied Black Liberation Front.) This was our local campus radio station, and the speaker was Tom Jones, Class of 1969, president of the group. Tom was a shape-shifter and somehow later shed his radical skin with a huge “gift” to Cornell in 1995. He went on to become the head of TIAA-CREF, the custodians, ironically, of my retirement money. But his threats were not hollow. Clinton Rossiter committed suicide. Allan Sindler and Walter Berns left Cornell. Physical assaults on faculty went unreported in the newspaper, but we heard about them at the Faculty Club. Black students, protesting his teachings about poverty, wrestled the microphone away from an economics lecturer, then walked in and took over the economics department. They went unpunished. Fire swept through the six-year BA-PhD program dormitory, and eight of the students died of asphyxiation. It seemed to have been arson, and this marvelous program was aborted, but the case was never solved. Charles Thomas, one of my advisees, told me that female black students chased him down and stuck him with pins for the crime of dating white girls.

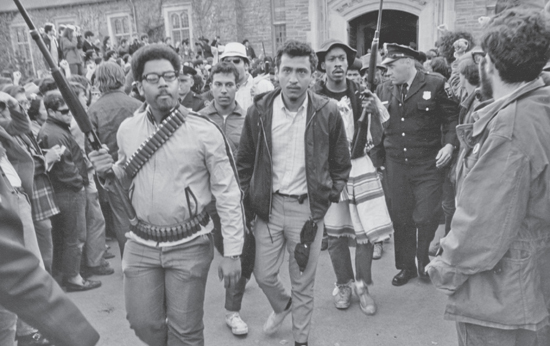

IT WAS PARENTS’ WEEKEND, April 1969. I reverted to my Quiz Kid role and was named captain of the Faculty College Bowl team. We planned to face off against four undergraduates to see who could answer trivia questions fastest. The contest was aborted as news of heavily armed black students swept the campus. The epicenter was Willard Straight Hall. A parent had either jumped from a window or been defenestrated, with at least a broken leg as a result. Bristling with rifles and ammunition, a large group of black students entered Willard Straight, threatened all those inside, and forcibly ejected them. They were now occupying the building, and the photo of the armed black students entering the Straight flashed around the world. The 1960s revolution had come to the Ivy League.

Rumors flew. A group of armed vigilantes was gathering near campus to retake the Straight from the “niggers and commie Jews.” President Perkins’s dog had been kidnapped. They had threatened to kill President Perkins’s children. They had threatened to kill President Perkins. What did the black students want? Their demands were nebulous—more black faculty members, more black students, more black scholarships—but one “nonnegotiable” demand stood out: amnesty.

The black takeover of Willard Straight Hall (April 18, 1969). Capping mounting intimidation against whites and nonmilitant blacks, members of the Afro-American Society violently took possession of the student union. This led me to quit my job at Cornell. Photo courtesy of Cornell Library.

The administration trembled. The faculty trembled. Emergency faculty meetings were held, and the meetings broke all attendance records. Max Black, the universally respected silverback of the philosophy department, urged, “When in doubt, stand on principle.” The faculty declined and voted to give the black students whatever they wanted, and most certainly, amnesty.

A minority of the faculty, including me, was scandalized. Relinquishing the freedom to teach what one believes, giving in to violence, allocating scarce resources to the loudest group for academically dubious projects like the Ujamaa Residential College—this was not what a university was about. A “Committee of 41” was formed and included the most distinguished of the centrist members of the faculty: Nobelist Hans Bethe, Paul Olum (later president of the University of Texas), Fred Kahn (later dean of the faculty), Max Black, and Dale Corson (who soon succeeded President Perkins). I was the forty-first, the token junior faculty member. The senior notables told me that they saw me as a future dean, someone who believed in traditional academic values. I did not see myself as a future dean or university president (my mother, however, would have loved me to have those roles), but I was honored to join their cause. Carl Sagan did not join. From identical experiences, he had moved far left, and I had become markedly more conservative. What I most valued in a university—arguably the best human institution ever created—needed defenders.

The last straw for me happened in my experimental psychology course. I’d prepared a lecture on intelligence. Arthur Jensen, a distinguished Berkeley professor of education, had recently published a well-reasoned but explosively controversial article in the Harvard Educational Review.11 He argued that IQ was heritable and that the IQ difference between American blacks and whites was genetic. He cited a bushel of evidence, such as the IQ gap remaining constant at every level of income. Jensen was vilified in the press. The ordinarily disinterested New York Times’s railing against Jensen notwithstanding, this was a very complex issue with serious arguments and counterarguments on both sides. It was also certainly a topic that would engage the students to come to grips with behavioral genetics. As I began my lecture, I noticed that several of my black students appeared to be scowling at me from the back row.

I was afraid. I even trembled. I stumbled on, omitting all mention of race and heritability. I was intimidated. I knew that the time for me to leave Cornell had come.

I voted with my feet.