In Dark Emu, Pascoe suggests that ‘Indigenous Australians wandering from plant to plant, kangaroo to kangaroo in hapless opportunism’ is ‘the accepted view’ (page 12). It has to be asked: accepted by whom? This has for generations been the ignorant and lazy view among those unwilling or unable to look into the subject for more than five minutes. People who take the question at all seriously, or who have read any reliable introductory published material of the kind I point to below, or who have found similar guidance in person or on television or the internet, know better.

Without survey evidence it would be hard to know for certain whether the educational efforts of the past fifty years or so, which I examine later, have made so faint an impression on the Australian public in the way Pascoe has suggested. In Chapter 10 of this book I cite numerous examples of introductory texts written for students and others over the past few decades that do not espouse this ‘accepted view’ that Pascoe positions in stark contrast with his own message.

Pascoe traces the discovery that Aboriginal people were ecological change agents who used fire to manage their lands to archaeologist Rhys Jones’s paper of 1969 (page 49). But Jones himself acknowledged a predecessor in Norman Tindale.1 In 1959 Tindale had published a paper, which Jones cited, containing these passages:

Man, setting fire to large area of his territory at all times of the year convenient for his hunting, often causes destruction far beyond that done by nature [that is, lightning].

Thus man probably has had a significant hand in the moulding of the present configuration of parts of Australia. Indeed much of the grassland of Australia could have been brought into being as a result of his exploitation …

Perhaps it is correct to assume that man has had such a profound effect on the distributions of forest and grassland that true primaeval forest may be far less common in Australia than is generally realised …

Next to the firestick the womans [sic] digging stick was probably the most effective instrument in altering the patterns of plant growth, removing a considerable portion of the more edible forms of vegetable life.2

Anthropologist Fred McCarthy referred to this passage at a conference in 1961; his conference paper was published in 1963.3 Ronald and Catherine Berndt cited the same passage in the section of their introductory text where they discussed traditional resource use by Aboriginal people.4 The same passage survived unaltered over the next few decades as the Berndts’ textbook went into multiple revised editions at least until 1988.5 For many years this was the standard introductory text on Aboriginal traditional life, past and present. Hundreds if not thousands read it.

It follows that Tindale’s proposition on the huge role of human-made fires was already on the public record in the 1950s and 1960s, when Pascoe was a young man and before Jones came up with a fetching label for Aboriginal fire use. Gammage, often relied upon by Pascoe, cites the Berndts’ book6 but not their reference to Tindale, nor Tindale’s own early flagging of the environment-changing and economic roles of fire itself. However, Gammage does acknowledge many of those who came after Tindale, from the 1960s onwards, and who found ‘sense and purpose in Aboriginal burning’.7

Tindale had his own problems with newness and resistance, on this very subject, back in the 1950s. In the same paper he said, ‘The picture of man’s effect on the Australian environment, lightly sketched in the above paragraphs, is not seen by all … It was thus possible even as late as 30 years ago [1929] to dismiss the Australian aboriginal as an ecological agent.’8

In Jones’s and Betty Meehan’s fifteen months in the bush in Arnhem Land in the early 1970s, they saw fires lit almost every day between March and January. The main purposes people gave them for firing the country in modest and mosaic patterns were to clear (and ‘clean’) it for ease of walking and tracking, and as an instrument of hunting. Game was harvested from freshly burned patches. Subsequent providing of green pick for marsupials and maintenance of grasslands free from trees do not seem to have been local objectives, or they were not mentioned, at least, in Jones.9

In his 1969 paper on ‘firestick farming’, Jones listed reasons why people burned ‘the bush’: for ‘fun’ or ‘custom’ (reasons I would not take at face value only); signalling one’s presence to others; to clear the way for travel and get rid of vermin; hunting; regeneration of plant food; and ‘extending man’s habitat’.10 He did not commit to a view that the last of these was deliberate.11

In the paper, Jones put quotes around the term he had invented: ‘fire-stick farming’. I do not believe he meant this literally, but it works very well metaphorically. He later said, ‘It was not entirely with tongue in cheek that I once called this “fire-stick farming”.’12 Even later, he said, ‘So, when I use the word “farming”, it isn’t just a tongue-in-cheek term. I meant to indicate that through the use of fire people were affecting the land in such a way as to increase the food available to them.’13 The fact that he did not literally identify this ecological agency as agriculture is made clear in the same paper, where he mentions the first successful claim to native title in Australia: the test-case claim on Murray Island (Mer) by Eddie Mabo, David Passi and James Rice on behalf of their families:

As a side issue I think it’s very interesting that Eddie Mabo came from that one tiny part of the present Commonwealth of Australia which was actually occupied by gardeners [that is, Torres Strait]. You know, these people are Papuan gardeners and, perhaps it’s too difficult to discuss these days because there’s so much politics attached to any discussion of these issues [that is, terra nullius], or any dissenting view. But it is interesting that the Mabo case was in that part of Australia that was occupied by gardeners, and I still wonder—had the [native title] test case been a place occupied by hunters and gatherers, would you have had the same result?14

The main purposes older Wik people gave me for firing patches of country in the 1970s were to harvest macropods and small grass-dwelling animals (especially mice and reptiles), and to make the country open and safe from snakes, safe for travelling on foot, and open enough to see long distances beyond camps, in case of threat. People indeed kept firing the country (see below15), especially in the season known as kathuk (‘burn-grass time’ in local English). If people want to metaphorically call that ‘firestick farming’, as Jones did in his 1969 paper, they well may, but producing young grass was never their main motivation in engaging in grass firing in the extensive Wik grasslands and thickets. I never heard of people intending fire to maintain grasslands free from trees, although this may well have been an effect of their actions.

The smoke also dissipated dangerous spirits, and kept the country tamed rather than feral. The adjective they use in Wik-Ngathan to turn ‘domestic dog’ (ku’) into ‘dingo’ (ku’ thayengun) means ‘wild’ or ‘untamed’. Country not regularly burned would become aak thayengun ‘feral country’, and could be said to be aak wuut-ul ‘country that has become reprobate’ (literally ‘an old man-already’). People also knew that firing incidentally led to green pick that drew marsupials to recently burned areas, but this was not its main purpose. The same observation that green pick was not a primary purpose of bush firing was made for the southern Tanami Desert people by Vaarzon-Morel and Gabrys.16 Latz and Griffin found the same for Central Australia more generally:

Fire was used mainly for short-term advantage in daily hunting and food gathering. People were conscious of the abundance of food plants after fire but saw this largely as a result of ceremonies performed to increase rain and food … Once burnt and the appropriate increase ceremonies performed, only then would the food plants produce in abundance.17

Wik people firing the country, middle Kirke River, Cape York Peninsula, 1977.

In his introductory essay to Marcia Langton’s 1998 book Burning Questions, Arnhem Lander Dean Yibarbuk has given us one of the best descriptions of the cultural, spiritual and economic roles of fire in a specific monsoon-belt Australian cultural location, in this instance the upper Cadell River of the Northern Territory.18 Similarly, Vaarzon-Morel and Gabrys have given us a rich account of contemporary firing in the Tanami Desert.19 An excellent continental survey of traditional fire use is provided by Philip Clarke in the chapter called ‘Fire-stick ecology’ in his 2007 book Aboriginal People and Their Plants.20

By the early 1980s it was well recognised among anthropologists of Aboriginal Australia that the pre-colonial economy was one in which people managed resources in a variety of ways, including firing the bush. Nancy Williams and Eugene Hunn put out a volume of papers by various authors on this theme in 1982 called Resource Managers: North American and Australian Hunter-Gatherers. In the introduction they said:

Yet a common finding unifies this collection: hunter-gatherers actively manage their resources, whether through strategic ecological or economic courses of action via social controls and political maneuver, or by virtue of the power of symbol and ritual. We can firmly reject the stereotype of hunter-gatherers as passive ‘food collectors’ in opposition to active, food-producing agriculturists.21 [emphasis in original]

In Burning Questions, which is not mentioned in Dark Emu, Professor Marcia Langton had already announced the death of the idea that pre-colonial Australians were simply hunter-gatherers and not also ecological agents. This was sixteen years before Dark Emu. She wrote:

Furthermore, as botanists, zoologists, anthropologists and geologists continue to investigate the complex relationships between Aboriginal culture, the plant communities, animal species and the physical environment in general, it emerges that complete dependence on natural bounty is a poor characterisation of the Aboriginal economy. It now appears that this economy has had a substantial impact on the environment which we characterise today as characteristically Australian.22

Eight years before Dark Emu, Langton reiterated the fact that the ‘mere hunter-gatherer’ model of Aboriginal people before European contact was something that lay in the past:

Economic approaches to pre-European contact history have evolved from an initial view of prehistoric Australians as simple foragers to a greater understanding of the complex connections between the social and physical dimensions of resource exploitation in hunting and gathering societies.23

Langton was nevertheless happy to describe the pre-conquest subsistence system of the peoples of Cape York Peninsula, perhaps by way of a convenient shorthand, as ‘their hunting, gathering and fishing economy’.24 No evidence of pre-conquest horticulture or agriculture can be found in Langton’s writings on the people of south-east CYP, with whom she carried out fieldwork for her PhD on their relationships with country.25

Tindale, long before Langton’s 1998 statement, was an explicit opponent of a simple ‘hunter-gatherer’ pigeonholing of Aboriginal economies:

In the past it has generally been assumed that the aborigines have always been a nonagricultural [sic] people and this may be true, yet some practices suggest that the very first steps may have been taken in areas along a path or paths leading to gardening, irrigation, and the partial domestication of animals …

Were the Mara and Alawa on the verge of becoming rice growers? They went each year to the same areas. Only one step, deliberate planting, was missing. The Alawa had even learned to store surplus food such as water lily seed in paperbark-lined pits in rock shelters; however there is no suggestion that this was ever used for planting.26

These people were, in short, gatherers and storers but not cultivators, at least not in the material sense.

The regionally differing degrees to which people intervened in the reproductive cycle materially, as opposed to ritually, are well illustrated here. Perhaps at the opposite end of the spectrum is Phyllis Kaberry’s description of the bush harvesting practices of the Aboriginal women among whom she lived in the Kimberley in 1934–36:

It is not the steady strenuous labour of the German peasant woman bending from dawn to dusk over her fields, hoeing, weeding, sowing, and reaping. The Aboriginal woman has greater freedom of movement and more variety …

Women then do not appear to be embryonic agriculturists in this part of Australia, in spite of the fact that many have worked on the stations and know something of gardening.27

Narcisse Pelletier’s seventeen years living with bush people in eastern CYP beyond the limits of colonisation apparently did not reveal any signs of agriculture of a kind familiar to a European. He was recorded as stating: ‘No-one plants and no-one sows’;28 ‘They seldom stay long in one place’;29 and ‘It would seem that these tribes spend their lives in hunting, fishing, and fighting, and never attempt any kind of cultivation.’30 However, he did make an early observation of plant management using fire: ‘I cannot see among these tribes any other branch of industry which seems to be even in the embryonic state, unless, from the agricultural viewpoint, we wish to consider the care the savages take in firing the woods where the yams grow so that the tubers of these plants develop more extensively and their crop is more plentiful.’31

Tindale provided several additional concrete examples of practices from different parts of Australia (also discussed in Dark Emu, though presented as if being revealed for the first time), including the turning-over of soil that is not a prelude to planting but a by-product of extraction, and the replacing of yam stems after the tuber had been removed, seed grinding, storage, and use of hunting nets.32 He even used the term ‘proto-agriculture’:

One of the important elements of proto-agriculture present among the Iliaura [Alyawarr] and other konakandi [hairy armgrass] users seems to have been the idea of storage. Food sufficient only for current needs was milled … Gathered surpluses were stored in caves for months so that women did not have to go food-gathering every day. That storage is not quite unknown elsewhere is indicated for both the Ualarai [Yuwalaraay] and Wadjari as indicated in later paragraphs; however the storage was always for use and never for returning to the soil.33

‘Proto-agriculture’ is not agriculture. It may well have been, instead, a long-term stable skill beyond which it was unnecessary to venture, and therefore was not proto-anything. We should not assume that it was ‘on the way’ to something other than its own continued effectiveness. The same applies to ‘incipient animal husbandry’.34 All these ‘incipient’ and ‘proto’ words, and expressions such as ‘on the pathway to agriculture’, suggest unfulfilled potential and assume an inevitable progression that has not been completed.

That a shift from hunter-gathering to horticulture and/or animal husbandry is not in every case a one-way journey is proven by those peoples who have shifted back from horticulture and pastoralism (stock herding) to foraging. For example, there was a reversion to hunting and gathering in the South Island of New Zealand between the initial settlement of Aotearoa by the horticultural Māori in about 1300 CE and circa 1700 CE.35 Around 5000 years ago in parts of Europe there was ‘a reversion to foraging in areas where agriculture had been practised’.36 In Africa, it is documented that Maasai and Kikuyu herders have at times reverted from pastoralism to hunting and gathering, and ‘some San communities have oscillated between foraging and cattle herding over several centuries—perhaps for millennia’.37 As Layton, Foley and Williams say, ‘These examples underline the danger of perceiving the transition between hunting and gathering and specialized husbandry as a one-way process that in some absolute sense constitutes progress.’38

The ‘incipient’ model of Aboriginal ecological agency suggests a deficit theory of Aboriginal culture. We need to grow out of that one-directional evolutionary mindset and respect classical Aboriginal culture and practice for what it was and is, not for what it might have become.

Although Dark Emu refers to Ian Keen’s 2004 book on pre-conquest Aboriginal economies (pages 130, 136), it does not consider his discussion of where these economies lie on the spectrum between foraging and agriculture. It is not possible here to do justice to Keen’s 436-page study, but after summarising regionally varying traditional Aboriginal ways in which bush resources were managed, he says:

These practices change our picture of Aboriginal hunting, gathering and fishing as a mode of subsistence. It involved a more radical intervention in the ecology than was recognised earlier, and, as Beth Gott remarks, the boundary between foraging and farming is blurred. The writings of David Harris are particularly relevant here; he constructs a continuum from dependency on wild plants and animals to dependency on domesticated ones. Even where production of wild plant-foods and animals dominates, it may be combined with cultivation involving small-scale clearing of vegetation and minimal tillage, and/or the taming, protective herding, or free-range management of animals. Larger-scale clearing and systematic tillage comes further along the continuum. ‘Agriculture’ involves more or less exclusive cultivation of domesticated plants, livestock raising by settled farmers, or transhumant39 or nomadic pastoralism …

In light of these discussions, although I have used the expression ‘hunters and gatherers’ to characterise Aboriginal subsistence practices, it might be more appropriate to classify Aboriginal subsistence production as that of hunter-gatherer-cultivators.40

Keen has since revised his opinion and removed ‘-cultivators’ from his description.41

If you read Keen’s 2004 book from cover to cover you will find plenty of references to vegetable food foraging, seed harvesting, fishing, hunting, and the use of fire to modify the environment, but there appears to be no evidence of soil preparation followed by sowing of seeds or tubers, which are the usual components of cultivation. This is in spite of one of Keen’s chosen areas of focus being the Barwon/ Darling rivers region and the Western Desert, where there was extensive harvesting and grinding of seed foods.42 His extensive index has no entries for garden(ing), sowing, planting or, indeed, cultivation. Pascoe’s presentation of his findings as new, and his frequent assertion of the ignorance of the Australian public, appear at least partly based on an unwillingness to acknowledge this kind of highly relevant published discussion and the direct teachings of Aboriginal people.

Pascoe does not appear to have ever probed the agriculture or gardening issue with senior and knowledgeable Aboriginal people who grew up living off the land, or whose older family members did. None of his topics appear to have been explored with elders who have retained traditional knowledge. He quotes white explorers freely, but not the words of traditional owners of Aboriginal land, and only occasionally the reports of those who have carried out in-depth research on Aboriginal traditions with living Aboriginal people. Pascoe is an armchair theorist.

In the early twentieth century, when cultural anthropology was still a developing social science, there were the great ‘armchair’ anthropologists of metropolitan Europe and America, who published books using the observations of others, and then there were the fieldworkers. Bill Stanner wrote that ‘the damage to our appreciation of Aboriginal life really came from the men of the armchair, who write from afar under a kind of enchantment’.43

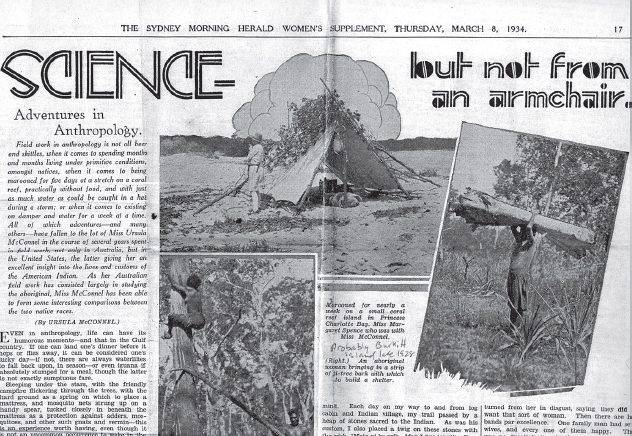

By the 1920s, professional field anthropologists were practising ‘participant-observation’ studies with Indigenous peoples (for example, Ursula McConnel; see below). This meant living among the people for extended periods of months or years, being immersed in local culture and language, and becoming socially competent in their hosts’ way of life. In the language of the times, their task was to understand things ‘from the native point of view’ and then educate their readers by translating that view into systematic knowledge and writing in a metropolitan language. One of the topics they usually covered in some detail was how people made a living—that is, how they obtained food and raw materials.

Fieldworker ursula McConnel writing for the Sydney Morning Herald.

To do all of this well required a strong dose of empathy, and it is well known that anthropologists historically have frequently translated that empathy and acquired knowledge into support for their hosts, politically as well as in defence against racial slurs and what in the early twentieth century was called ‘maltreatment of natives’. Anthropologists like AP Elkin, Donald Thomson, McConnel and Olive Pink were in the vanguard of the fight against the assimilation policy decades before it was rescinded. I have elsewhere gone into the evidence for this activism by anthropologists in the Australian case in the years 1925–60.44 Since that time, Australian anthropologists’ activism in support of Indigenous causes has only increased. It has not been an absence of goodwill that has prevented them from saying that the Old People were practising agriculture.

On the basis of what I have learned from senior Aboriginal mentors over a period of fifty years, it is clear to me that the non-adoption of horticulture and agriculture by the Old People was not a failure of the imagination but an active championing and protection of their own way of life and, when in contact with outsiders, resistance to an alien economic pattern. These were and are people easily confident in the bush, and proud of their ability to run an economy that had minimal negative impact on their countries.

Anthropologist Athol Chase worked long and intensively with people of north-east CYP, who are now mostly based at Lockhart River settlement. He made a special study of people’s relationships with the flora and fauna of their world, including their botanical knowledge and their hunting, gathering and care for their countries. He reported on their resistance to gardening and agriculture:

For the Umpila, Kuuku Ya’u, and other Aboriginal peoples of this immediate area, agricultural practices are a wasteful and illegitimate activity in the landscape—‘It is not our way; it is alright for other people. We get our food from the bush’ … Despite enormous pressures by a government of European derivation to assimilate them into a European perspective of society, economy, and religion, there is a stubborn resistance to such shifts in beliefs …45

Such pressures were exerted by mission and government authorities alike as in the case of Lake Condah (Victoria): ‘The Aborigines will not cultivate their own gardens unless some pressure is brought to bear upon them to compel them to do so.’46

Early Northern Territory missionary Father Francis Xavier Gsell recalled local reactions to the first establishment of a mission garden on Bathurst Island (see below):

Watching us sowing, they grumbled: ‘What a pity to lose all this food, these potatoes, yams, and ground-nuts. In the earth they will go bad and be of no use to anybody. If,’ they said finally, ‘you really want something to eat, sing a song to the spirits, dance a dance, and you’ll get all the food you want.’47

From a similar source and era, Yirrkala missionary Wilbur Chaseling recalled that ‘When it came time for planting it seemed ridiculous to the nomad to bury good sweet-potatoes instead of eating them …’48 During the same phase at Milingimbi, Ella Shepherdson recalled:

Catholic missionaries: Sisters of the Order of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart of Darwin.

Garden work has always been an uphill struggle because our Aborigines were not very interested in it. However there are now a number who have gardens of their own and work hard in them.

When we first went to Milingimbi, the men had to be taught to use the old Fordson tractor for ploughing the ground and preparing it for crops of cotton, maize and millet in the first instance then sweet potatoes, cassava and peanuts at a later stage. When they saw good food being put into the ground, this to their way of thinking was a waste, and often it would be dug up and eaten.49

Ronald and Catherine Berndt reported a snapshot of this kind of resistance from their own experience in a nearby region:

An Arnhem Land woman once said, in effect, rather patronizingly, as she watched a Fijian missionary working in his mission garden, anxiously concerned because a few of the plants had died: ‘You people go to all that trouble, working and planting seeds, but we don’t have to do that. All these things are there for us, the Ancestral Beings left them for us. In the end, you depend on the sun and the rain just the same as we do, but the difference is that we just have to go and collect the food when it is ripe. We don’t have all this other trouble.’50

They followed that passage with examples of traditional resource conservation such as not collecting all the yams from any one location, ‘sprinkling seeds around’ (details not given), preserving valuable trees, and not spearing stingrays when they were breeding.51 They added: ‘Holding this view, that nature is their garden, and one which they need not cultivate or “improve”, means of course that the Aborigines were not able to vary the range of foods available.’52

In 1974, I participated in a field trip to map Johnny Flinders’ country and its neighbours in eastern Cape York. Flinders spoke with a briefly visiting geographer, David Harris of University College London, who asked him why his people did not sow plants to make food. Flinders’ brief reply was: ‘No, he grow himself!’

In the early 1980s senior Kuku Yalanji man Johnny Walker of Bloomfield, south-east Cape York, told anthropologist Chris Anderson that the Old People were mystified by the missionary obsession with agriculture. He said something like: ‘Bama [Aboriginal people] know where to get mayi [vegetable food] already, why should we stay in one place and have to hoe and bother with a farm!?’53

And yet there are also many accounts of people adopting the planting of sweet potatoes, watermelons, pumpkins, cassava and similar exotics, with missionary support. This kind of horticulture occurred at Garttji Lagoon in Arnhem Land after missionary Edgar Wells introduced it to local people,54 and Lazarus Lamilami recalled his age group being taught how to grow things, including potatoes, corn, cassava and pumpkins.55

In classical Aboriginal philosophy, the Dreaming basis of the biota ensures an eternal cycling of birth, life, death and renewal. Warlpiri elder Engineer Jack Japaljarri explained this to me once by using native honey bees as an example. Twirling his forefingers in a rotating movement, he said, ‘That Dreaming, he rollin’, he rollin’, like honey bee, live one, dead one, live one.’ This was not Asian reincarnation belief, it was the depiction of an unchanging cycle of life and a subsistence system underpinned by the Dreaming ground of being. It was not valorising the achievements of clever, ingenious, creative human beings. And it was embedded in a philosophy free from the ambiguous enchantments of notions of progress.