This book is about a debate over how Australia’s First Peoples lived, and made a living economically, before conquest by the British Empire. Were they farmers, hunter-gatherers, or something in between?

The issues have come to be debated by a wider than merely academic public since Bruce Pascoe published his book Dark Emu: Black Seeds: Agriculture or Accident? in 2014. Here, Dr Keryn Walshe and I approach the relevant facts and interpretations from a scientific and scholarly point of view, as free as possible from identity politics and racial polemics.

I have described our focus as on Australia ‘before conquest’, not ‘before settlement’, for some very good reasons. Australia was not ‘settled’ in or after 1788 by British, Asian and other non-Aboriginal people, as if the lands were void of human societies. ‘Settlement’ is accurately applied to the occupation of previously uninhabited lands, such as the Norwegian migration to Ísland (Iceland) and the Māori migration to Aotearoa (New Zealand). It is not an accurate description of the uninvited imperial British invasion of Australian First Nations’ territories, followed by the subjugation and displacement of the Indigenous Australians who were the lands’ owners. While this usurpation was happening, Aboriginal land tenure systems were ignored—and replaced, in the eyes of the colonials, by property laws imported from England. It was not until 1992 that Australian law recognised that pre-existing Indigenous titles of 1788 could, to varying degrees, have survived these usurpations, and the living native-title holders of certain lands and waters could be acknowledged as such.

The real ‘discoverers’, ‘pioneers’ and ‘early settlers’ of Australia— the people who actually ‘opened up the country’—were the people who arrived around 50,000–55,000 years ago (see Appendix 1), when what are now New Guinea, mainland Australia and Tasmania were a single landmass known today as Sahul. They are rightly called the First Australians, and their descendants have in recent years been accurately referred to as First Nations People. For longer, in recent centuries, they have been known as Aborigines or Aboriginal people. These terms also refer to First People, because they derive from the Latin expression ab origine, which means ‘from the beginning’. There is therefore nothing at all disrespectful about ‘Aboriginal’ as a term, and we use it here accordingly. It stresses primacy. We also refer to the pre-colonial Aboriginal population as the Old People, because that is what their descendants commonly call them, and because it also is a term of respect.

Our subject is a now-famous book about Australia’s First People and their way of life before conquest: Dark Emu, by Bruce Pascoe.1 In Dark Emu, Pascoe sets out to overthrow what he regards as the falsities of past accounts of classical (that is, pre-conquest) Aboriginal ways of life. He argues that, in contrast to what most Australians have been told and believe, at the time of European invasion Aboriginal Australians practised agriculture, stored food, built and lived in large numbers in substantial dwellings and permanent villages, and sewed clothes. He argues further that Aboriginal people having lived in this manner constitutes evidence of their ‘advancement’, of a ‘level of development’ that has not previously been recognised. He writes to correct these untruths and enlighten his readers.

We contend that Pascoe is broadly wrong, both about what Australians have been told of pre-conquest Aboriginal society and about the nature of that society itself. We also take issue with the notion that recognisably European ‘settled’ ways of living, focused on material and technical ‘development’ in food production, are in any way to be valued more than the ways of living that existed in Australia before invasion. In the light of these contentions, and the extensive evidence we present in support of them, we ask how and why Dark Emu has become the phenomenon that it has. Is it time for all Australians to take more responsibility for learning about Aboriginal society, and to demand more careful attention to questions of historical and other truths?

Throughout Dark Emu, Pascoe puts a high value on technological and economic complexity as a standard of a people’s worth, and then seeks out examples of these complexities in classical Aboriginal life. In his words, such complexities are signs of ‘advancement’. He doesn’t employ a term for lack of advancement except for the ‘social backwardness’ he says others have attributed to a perceived lack of pottery and storage among Australians before conquest. He says, ‘This attitude prejudices opinion about the level of development of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’ (page 105).

As noted, the key areas in which Pascoe seeks to find corrective examples to false estimates of this ‘level of development’ are agricultural food production and storage, substantial dwellings, settlement in permanent villages, high numbers of people in the villages, and the sewing of clothes. The evidence he provides for these subjects is selected in such a way as to compensate for what he believes is a falsely assumed simplicity or crudity—even a ‘brutishness’ (page 100) before conquest by the British Empire—attributed to Aboriginal people by today’s Australians.

All of these subjects belong to the world of the material. For that reason, they may be more readily grasped by the average reader than the complexities of Aboriginal mental and aesthetic culture: those highly intricate webs of kinship, mythology, ritual performance, grammars, visual arts and land tenure systems. Dark Emu does not enter into the non-physical complexities to any real degree. Like its major sources, Bill Gammage’s The Biggest Estate on Earth2 and Rupert Gerritsen’s Australia and the Origins of Agriculture,3 it is largely confined to material economic behaviour and often separated from meaning, from intent, from values, from culture, from the spiritual, and from the emotional. This disconnect, we suggest, is the book’s biggest gap.

In the present book, Keryn Walshe brings to her chapters (12 and 13) a wealth of scholarship and field site work with Aboriginal collaborators, as an archaeologist.

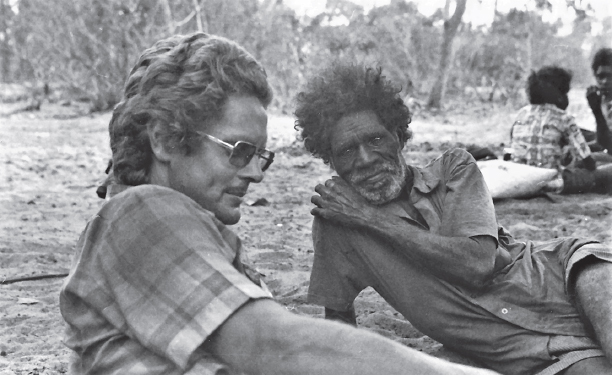

My own contributions draw on wide reading in the anthropology and linguistics of Aboriginal Australia, but, most importantly, are derived from facts and insights I have been given directly by senior Aboriginal people of knowledge. I am here passing these on, and as such, giving back. Over the past fifty years I have been carrying out collaborative research with Aboriginal people, in many cases in remote regions, including Cape York Peninsula (CYP), western Arnhem Land, Daly River, the Murranji Track, Central Australia, and the corner country of the Lake Eyre basin. I have also worked with people in urban and rural regions. In three cases (eastern Cape York, western Cape York, and north-central Northern Territory), I have been taken as a son by senior men and incorporated into their families (Johnny Flinders, Victor Wolmby, Pharlap Dixon Jalyirri). I have given the names and language groups of my principal teachers in the Acknowledgements. Under the tutorship of those Aboriginal mentors, I have recorded, on site, several thousand places and their cultural and historical significance, including in many cases their botanical and faunal resources and how those resources were garnered and in what seasons. Three men of highly specialised botanical learning stand out: Noel Peemuggina and Ray Wolmby (Wik people, western CYP), and Pompey Raymond (Jingulu, Murranji Track region, Northern Territory).

I have recorded many Aboriginal languages and learned to speak three by month after month sitting at the feet of teachers whose languages were still spoken, yet unwritten. And—I note this as it is relevant to later discussions—I’ve done my share of hunting and foraging in days gone by, when I was the only non-local person living with Wik people for months in the wetlands country north of the Kendall River in CYP in the 1970s. All of our protein and fat came from hunting.

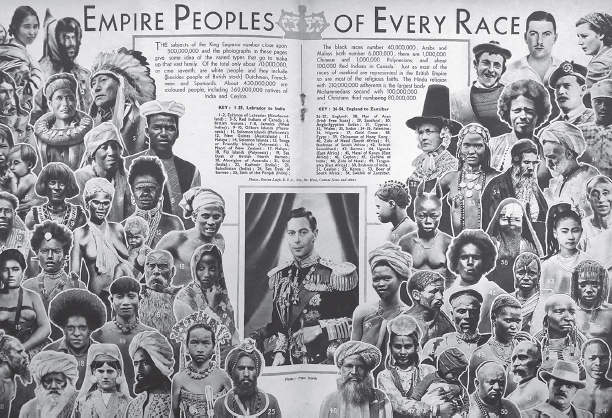

Through Dark Emu, Pascoe has engendered much interest within Australia in the history of the nation, the traditional ways of life of Australian Aboriginal peoples, and past and present relations between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians. He builds awareness of the fact that British Empire colonists in Australia assumed their own superiority and justified conquest, slaughter and massive land theft on that basis (pages 12–13, 154). Internationally, the British Empire was the greatest kleptocracy in human history (see opposite).4

Pascoe popularises the work of Bill Gammage on the evidence for pre-1788 environmental management, principally through the use of fire, and on related topics (pages 20, 26, 42, 54, 79, 117, 121, 123, 128).

He also brings attention to Gerritsen’s Australia and the Origins of Agriculture, an amateur but densely scholarly and demanding work that has been controversial among specialists.5 This is his most frequently used source.

Pascoe also popularises part of the important work by Paul Memmott, who presented the first comprehensive survey of classical-period Aboriginal dwellings.6

The British Empire and its ‘races’ in 1937.

Pascoe contradicts the false belief, perhaps held by some, that all Aboriginal people were naked all of the time. Some Aboriginal people sewed animal skins into cloaks (page 89).

He criticises the uninformed view that classical Aboriginal society consisted of constantly nomadic people who simply lived off nature’s bounty, were not ecological agents, did not stay in one place for more than a few days and did not store resources (for example, page 12).

And he gives considerable attention to the storage of foods (pages 105–14), this being a useful corrective to ignorance of Aboriginal storage methods.

Even here, however, the answer to the false belief that Aboriginal people stored nothing is not to assert that they universally amassed major stores of food. Many people stored a few food sources for shorter or longer periods, differing by region, and some stored almost nothing. Different climates set up different challenges for storage. Deserts were more friendly than hot, humid tropics. After long experience with bush-dwelling people in the Mitchell River area of CYP in the 1930s, trained anthropologist Lauriston Sharp noted that they were at one extreme end of the storage spectrum: the only item they stored beyond a day or two was the nonda plum.7

To Pascoe’s examples, a good number of them drawn from Gerritsen, could be added many more. Philip Clarke has provided a brief survey of evidence as to traditional storage that complements Pascoe’s.8 Clarke’s examples are mainly, but not only, drawn from the arid zone. One could also add, from the wet monsoon belt, the following. In the 1970s in the case of the Wik region of CYP, where I did intensive fieldwork with people who in many cases had been born and raised beyond the reach of the British Empire, I found that:

Limited food storage was practised. Nonda plums (Parinari nonda F. Muell. ex. Benth.) were dried on the rooves of shelters, or collected dry from the ground (the dry form even has a different name), and were kept for some weeks after their season of superabundance. Long yams (Dioscorea transversa R. Br.) were stored in the sand for weeks and even months.9 Long-necked turtles might survive a day or two trussed up, and in the Big Lake area barramundi is said to have been cooked, wrapped in paperbark, and buried in the cool earth for eating days later. Most food, however, was eaten within twenty-four hours.10

In the course of discussing Dark Emu in this book, we engage with the problem of labels for kinds of people that are focused on their economic lives. This problem looms large in Dark Emu. It should not be lightly dismissed on the grounds that names for types of subsistence are merely tags. The debate here is over not just labels but the way subsistence types are classified and compared.

In a talk given in 2018, Pascoe said:

In 2014 I wrote a book, Dark Emu, which exploded the myth that Aboriginal people were mere hunters and gatherers and did nothing with the land. I wrote the book because I found it hard to convince Australians that Aboriginal people were farming. Using colonial journals, the sources Australians hold to be true, I was able to form a radically different view of Australian history. Aboriginal people were farming. There’s no other conclusion to draw.11

A little further on in this speech, he refers to ‘the ancient agricultural economy’ of Australia. This central plank of Pascoe’s theory is one we put to the test.

Pascoe’s message is built on a simple distinction between what he calls ‘mere’ hunter-gatherers, on the one hand, and farmers; or between ‘mere’ hunting and gathering on one hand and ‘agriculture’ on the other. We consider that the evidence, in fact, reveals a positioning of the Aboriginal people of 1788 somewhere between these two extremes: they were complex hunter-gatherers, not simple farmers. The Old People in 1788 had developed ways of managing and benefiting from their landscape that went beyond just hunting and just gathering but did not involve gardening or farming. They were ecological agents who worked with the environment, rather than, usually, against it. They frequently used slow-burning fires to make their landscapes more liveable. However, they did not cut down bush to clear the land, plough and hoe the soil in preparation for planting, or then sow stored seed or tubers or rootstock in gardens or in fields.12

As is often pointed out, all human beings were hunter-gatherers— also known as foragers—for over 90 per cent of our history as a species, until the agricultural revolutions that began around 11,000 years ago in south-west Asia, in the Fertile Crescent. Agriculture also developed later and independently in parts of China, New Guinea, Sub-Saharan Africa, Central and South America, and the Mississippi Basin of the eastern United States of America.13 Agriculture thus developed in what are archaeologically rather recent times on all the inhabited continents except Australia. Here, foraging, augmented by various ways of modifying the environment, was a highly successful economic adaptation, as it also remained in south-west Africa, the sub-Arctic Circle, parts of California and a number of other locations around the world, until the impact of colonisation.14

We do not propose here to engage in a lengthy coverage of the various debates that have been held over the semantics of the words ‘foraging’ (also referred to as ‘hunting, fishing and gathering’), ‘horticulture’ or ‘agriculture’. Our own working definitions used in this book are both readily understood by non-specialists and compatible with definitions given in the authoritative Dictionary of Anthropology.15 For example: ‘Foragers are peoples who subsist on hunting, gathering, and fishing with no domesticated plants, and no domesticated animals except the dog.’16 As discussed elsewhere in this book, this needs to be augmented with recognition of foragers’ roles as skilled ecological agents.

By contrast, ‘Horticulture is a mode of subsistence agriculture that involves small scale farming or gardening practiced with simple hand tools, such as the digging stick, and without the use of the plow or irrigation.’17 One of the main forms of horticulture is ‘swidden horticulture’, also known as ‘shifting cultivation’ or ‘slash-and-burn’. An area of forest is cleared and burned, and the area is gardened, and later abandoned, after exhaustion of nutrients, for a new plot. Swidden horticulture is practised on the larger northern and eastern islands of Torres Strait, but was practised nowhere in pre-conquest mainland Australia.18

By contrast again, ‘Agriculture is the deliberate growing and harvesting of plants, but the term is often extended to include the raising of animals … Agriculture always involves more, technically and culturally, than just planting and harvesting crops.’19

The difference between horticulture and farming is usually regarded as mainly one of scale, between small-scale cultivation and field cultivation respectively. In German the distinction is between Gartenbau—‘horticulture’, from ‘garden (Garten) building (Bau)’—and Ackerbau—‘agriculture’, from ‘field (Acker) building (Bau)’.20

We regard Peter Bellwood’s definition of ‘cultivation’ as appropriate, and one that would have very wide support:

Cultivation, an essential component of any agricultural system, defines a sequence of human activity whereby crops are planted (as a seed or vegetative part), protected, harvested, then deliberately sown again, usually in a prepared plot of ground, in the following growing season.21

Some peoples combine two or even three modes of subsistence. For example, some Torres Strait Islanders, depending on which islands, traditionally combine fishing, hunting and gathering with a little horticulture, while others combine fishing, hunting and gathering with intensive horticulture.

Dark Emu sets up a simple distinction between agriculturalists living in ‘permanent housing’ and the ‘hapless wandering’ of the ‘mere huntergatherer’,22 choosing to conclude that the former is the truth and the latter a widely accepted lie about Aboriginal Australia before colonisation. There seems to be an assumption here that subsistence based on hunting and gathering is itself not complex. This is far from the truth.

Setting aside the various proactive ways in which Aboriginal people at conquest modified their environment and its resources, the hunting, fishing and gathering economy was far more complex than might be imagined from the word ‘mere’. As an economic process it was at least as complex as gardening or farming, if not much more so. Agriculture can get by with knowledge of a small range of flora and fauna. Hunting and gathering can’t.

Hunting and gathering in pre-colonial Australia required fine-grained knowledge of hundreds of species and their habitats, annual cycles, names and generic classifications; of methods for processing them and for preparing them as food, as tools, as bodily decoration, and as ritual paraphernalia. It required what repeatedly seemed to colonial newcomers to be almost supernatural eyesight, seeing things in the far distance or among foliage that no colonial could see.

Allied to this, it required the ability to track game using often infinitesimal traces left on the ground or in foliage. It required tremendous spatial and narrative memory, of the kind many of us now have very much lost through reliance on paper maps, written records and Google Maps. It required high skills in lithics (stone tool manufacture) in order to reveal from within the rough stone the elegant tools now found in museums and in the bush. And it required deft and precise skills in using weapons and wielding digging sticks, nets, lures and traps. Spearing fish required the ability to calculate instantly how refraction through water needed to be corrected for during the throw (see below).

Even ‘mere’ hunter-gatherers would have been resource experts on their own ground, but Aboriginal people were hunter-gatherers-plus.

It might have been better if labels like ‘hunter-gatherer’ and ‘horticulturist’ and ‘agriculturist’ were not so prominent in these debates, as Harry Lourandos has proposed.23 They can sometimes attract outdated evolutionary schemes that operate on the discredited ‘primitive’ versus ‘advanced’ scale, also known as social evolutionism. We provide evidence below that Pascoe has resurrected social evolutionism in his text, both in words and in the way records are evaluated in Dark Emu.

Bruce Yunkaporta spearing a stingray, Wooentoent, Kirke River, Cape York Peninsula, 1976.

In Dark Emu the author uses the presence of ecological agency, such as the firing of country and the conservation of species or the storage of food, as a pathway to reclassifying pre-conquest Aboriginal people as an agricultural people. On this basis all human beings might have been classed as agricultural people for hundreds of thousands of years until the present. But this semantic shoehorning submerges a distinction that is not merely one of economic type, but one of sheer power. The differences between hunter-gatherers(-plus) and settled agricultural farming peoples have been played out in a series of unprecedented and cataclysmic shifts in human history. Bellwood, an authority on the emergence of agriculture, describes these shifts as ‘episodes of massive cultural and linguistic punctuation’.24

The rapid emergence of settled crop-growing agricultural societies beginning about 11,000 years ago in south-west Asia, and from there reaching west to the British Isles by about 5000–4500 BP (before present), led to ‘dramatic cultural change and population growth’.25 It has been described by Israeli archaeologists Bar-Yosef and Kislev as ‘a revolutionary subsistence strategy’.26 This revolution in turn led to the conquest, displacement, assimilation and absorption of almost all of the foraging peoples of Europe within about 4000 years.

In turn, the descendants of those Neolithic farmers who moved west from the Levant region became the European nations that expanded themselves by way of colonial conquest around the globe, especially from the seventeenth century to the nineteenth. These agrarian societies were land-hungry, populous, technologically complex, armed with the modern weapons of the day, in charge of a range of domesticated animals, and imbued with the idea of their own superiority over ‘natives’ as part of the justification for their conquest of allegedly ‘new’ lands.

The shift from hunting and gathering to farming was therefore a quantum leap in human economics and geopolitical power, accompanied as it was—at least in the Eurasian case—by the unprecedented development of towns and cities, population explosion in fixed settlements, animal and wheeled transport, metals and the powerful weapons made from them, and a hierarchical social organisation that made large-scale warfare and the concerted invasion of other lands more than possible.

So, if the Old People of 1788 can be pigeonholed at all, we would prefer the label ‘hunter-gatherers-plus’—not ‘agricultural people’, the badge of their conquerors. We go into the many varieties of ‘plus’ later.

The Australian people of the pre-conquest era did not avoid agriculture because they didn’t know how plants grow. The proposition would be absurd, given they were acute observers of the plants around them and the plants’ life cycles. Instead, they regarded the fertility and the reproductive spark that maintained plant populations via seeds to be spiritual, not a matter of secular human technology. Many have argued that Australia lacked plants and animals suitable for domestication and was limited by its aridity and uncertainty of rainfall, concluding that this prevented the development of agriculture. But others have pointed out that some Australian plant species are very similar to those that were being cultivated just to the north in Torres Strait or New Guinea.27

Plants suitable for domestication were introduced to north Australia before colonisation of that region. They were planted by visitors such as the Buginese and Macassans, and included betel nut palms, coconut palms and tamarind trees—but Aboriginal people did not adopt the practice of planting them.28

Coconuts also arrive irregularly on many of Australia’s northern beaches, drifting in on the tides. That they have done so for a very long time is reflected in the words for coconut in several north Australian languages. While some are borrowed from English (for example, guganat, Burarra, guginarr, Yidiny), many are old Indigenous words, including galuku (Gupapuyngu) and arlipwa (Tiwi). Old words for coconut among CYP languages include thiineth (Wik-Ngathan), kuunga (Kuuku-Ya’u), warapa (Umpila), olulul (Wurriima), gamyarr (Morrobolam) and wuyngkayi (Umpithamu). There is no evidence that north Australian Aboriginal people created coconut plantations before colonisation; they did eat the coconut flesh from the nuts that drifted ashore.

Another reason why the ‘lack of plants suitable for domestication’ argument is flawed is that there are plenty of Australian trees with edible fruit that are readily propagated from either seed or rootstock or both, but that were not used to create orchards before colonisation. The macadamia nut, the lady apple, the nonda plum and the quandong are good examples among a very large number.

Can we be sure that an absence of Aboriginal horticulture in 1788 means that it had never been practised before then? A genetic study by Hunt, Moots and Matthews has found that the wild taro of an area near Cooktown, Queensland, breeds naturally, but the data do not exclude the possibility that it may have had a history of domestication in the past.29 Note that another edible tuber found in the same location may have been introduced from the eastern Papuan tip, given that the Cooktown language has wugay for the yam species Dioscorea sativa rotunda. Ray Wood has sourced this term, and the equivalent term kuthay of north-east CYP and Torres Strait, to the eastern Papuan tip.30 There is also the hypothesis that a species of banana (Musa acuminata), a wild taro (Colocasia esculenta) and the greater yam (D. alata), which are found in north and north-east Australia, may have been subject to experimental horticulture—an experiment later abandoned—during a period when Australia and New Guinea were still a single landmass, that is, more than 10,000 years ago.31 The hypothesis remains unconfirmed.

Although domesticable species in Australia may have been limited, as a factor in the absence of adoption of agriculture it is more important that the Old People did not see any necessity to go beyond their existing environmental modifications, given their deep commitment to the maintenance of fertility through engagement with the spiritual powers left for them by the Dreaming. After all, even in regions on other continents where there were species eminently suitable for cultivation, human beings lived for countless centuries as hunter-gatherers before changing to being farmers. The economic switch was not triggered by the presence of domesticable species, but by something else, something cultural, a shift of mindset.

A reviewer of the manuscript of this book suggested that spiritual practices were no bar to the shift to agriculture in other societies. Plenty of other peoples who used religious practices to do with species propagation were also gardeners and farmers and had stopped being hunter-gatherers per se. ‘Garden magic’ was most famously reported from New Guinea by Bronislaw Malinowski in 1935.32 But shifting from foraging to gardening-and-foraging does not entail the abandonment of spiritual beliefs and practices to do with the fertility of resources: it entails the augmenting of religious propagation, environmental agency and hunting, fishing and gathering with horticulture and its magic.

In Chapter 2, I provide plentiful evidence that this positive spiritual propagation was maintained in classical Australia by human reverence and direct action, but on the basis that the elemental forces of life are there forever, from the Dreaming, the spiritual ground of being. They are not created by human ingenuity. Humans can only stimulate the emergence of such latent powers in the cyclical regrowth of plants and animals, and in the supply of rain.

This commitment to the non-physical basis of reproduction in the biota was also the Old People’s basis for resistance to the gardening and agriculture methods of their Melanesian neighbours at Cape York, and to those of the European colonists who tried so hard to convert them to agriculture, and who failed—not always, but mostly, at least for a time (see Chapter 6).33

Pascoe links gardening and cropping to the settled life—that is, to what is sometimes called sedentism. Given the extent to which Dark Emu owes a debt to the work of Bill Gammage, it is unfortunate that Pascoe effectively rejects him on the question of sedentism. Gammage said:

Neither in Australia’s richest nor poorest parts, by European standards, were people tempted to settle. Instead they quit their villages and eels, their crops and stores and templates, to walk their country.

They were mobile. No livestock, no beast of burden anchored them. They did not stay in their houses or by their crops.34

Gammage also noted the way Aboriginal people rejected European gardening, and included the Torres Strait example that we discuss elsewhere:

In the north they knew about farmers. Cape York people traded with Torres Strait gardeners, and Arnhem Landers watched Macassans and Baijini from the Indies till land and plant rice, tamarind and coconuts, build stone houses, wear cloth, make pottery and feed domestic fowls, dogs and cats. Some visited the Indies. None copied either group, instead maintaining typical Australian templates.35

Gammage’s focus, like Pascoe’s, is on defining the people’s activities behaviourally and materially, not philosophically. This is economics without religion, something inconceivable to the Old People. Gammage argues, though, that they were farming but not farmers, given that they were doing most of the things farmers did but not all of them: ‘So people burnt, tilled, planted, transplanted, watered, irrigated, weeded, thinned, cropped, stored and traded. On present evidence not all groups did all these, and few Tasmanians may have, but many mainlanders did. What farm process did they miss?’36

This sweeping passage is highly debatable, even with the caveats of ‘not all groups’ and ‘few Tasmanians’. It bears the same crippling flaw as is found in Gerritsen’s slippage from assembled fragments to continental Australian assertions, a flaw identified at the time by CSIRO research scientist Fiona Walsh:

It will be debated if he [Gerritsen] has overstated the role of intensification and food production …

Gerritsen has also, to some extent, located the practices and technologies that he reports in relation to Aboriginal socio-political and language groups. However, his extrapolation from isolated observations across wide geographic regions is highly questionable.37

Of more immediate concern here is that Gammage’s assemblage of behaviours conjures up a kind of culture-free and philosophy-free zone in which these material activities—scattered, tenuously reported and never all reported together—seem to have a life of their own. It is of more immediate relevance that even though Pascoe goes much further than Gammage on certain questions, such as sedentism, both share the giving of scant (at best) attention to spiritual propagation of the whole biota and the active stimulation of certain valued species and of rain, as an embracing template on which behaviours rested.38 Gammage’s ‘template’ is un-sacred.

Pascoe’s attempt to fit the evidence into the ‘farmers’ category (for example, page 26) leads him to mythologise both history and Aboriginal culture, and to ignore the spiritual propagation culture of the Old People. He is in this way as much a myth-maker as a myth-buster. He also consistently pushes the evidence of Aboriginal subsistence beyond what it can factually bear and into a European model of economic life. It is almost as if the more European the Old People can be made to seem, the better. As suggested above, this is Dark Emu’s most fundamental flaw.

For the Old People, their means of making a living and obtaining materials for artefacts were inseparable from their commitment to a spiritual understanding of the origin of species, to conservative values in relation to change, and to a cosmology in which economics had to be in conformity to ancestral authority. Hunting, gathering and modification of the environment through fire and other means were a dimension of how the Dreaming—the ultimate spiritual foundation of life—left things forever. Practice followed cosmology. Gathering and hunting and fishing were not just economics: they were the Law.

Under that Law, people employed supernatural, sometimes esoteric ways of ensuring the regrowth of plants and the resurgence of animal populations, for successful hunting, for ensuring water flow in wells, and even, in one region, for creating pet crocodiles for use against enemies. People also engaged in ritual and musical performances to manage their meteorological environment, including making rain, fending off lightning, bringing on specific winds, preventing cyclones, and, in one case, hastening the shortening of the night at the winter solstice through song. These are all further explored in this book.

Through clan and personal totems, people also had shared substance with the species of their places of belonging, and with other phenomena. Clan totems, when they were species of plants and animals (not all were), were typically native to the ecological zone of the clan’s country or estate. There were no mere plants or animals as economic objects, and there was no wilderness to conquer through cleverness.

For many of those who knew nothing about the book’s subject matter before reading it, Dark Emu seems to have come as a revelatory experience. Indeed, Pascoe is often at pains in the book to make reference to the ignorance of his fellow Australians and to the newness of what he has to say. His depiction of Australian history as telling students nothing about Aboriginal people’s ‘agricultural’ past is correct, because no one in a true position to teach the subject has believed that was the case; but his implication that educators have failed to tell people anything about Aboriginal resource management and semi-nomadism (as against ‘hapless wandering’) is simply false, as we also demonstrate below. This includes students’ texts covering many decades in which a ‘simply nomadic’ description of the Old People was rejected. We quote from them later.

Dark Emu’s claims to debunking myths are unfounded. This article appeared in The Guardian seven years before Dark Emu was published:

SCIENTIST DEBUNKS NOMADIC ABORIGINE ‘MYTH’

Before white settlers arrived, Australia’s indigenous peoples lived in houses and villages and used surprisingly sophisticated architecture and methods to build their shelters, new research has found.

Dwellings were constructed in various styles, depending on the climate. Most common were dome-like structures made of cane reeds with roofs thatched with palm leaves.39

Some of the houses were interconnected, allowing native people to interact during long periods spent indoors during the wet season.

The findings, by the anthropologist and architect Dr Paul Memmott, of the University of Queensland, discredits a commonly held view in Australia that Aborigines were completely nomadic before the arrival of Europeans 200 years ago.40

Is it possible for the same myth to be debunked twice? Perhaps serial debunking is necessary if the public keeps forgetting previous debunkings. This is not in any way to belittle Memmott’s wonderful book, but it does reflect the problem of making mass media news out of a complex subject. Sometimes, it seems, truth has to be reduced almost to ashes.

Is not that journalist’s expression ‘surprisingly sophisticated’ a failure of respect for Indigenous people and, indeed, a metropolitan put-down? Dwellings that function to meet people’s needs, whether they be elementary or more complicated, are hardly ‘surprising’; and ‘sophistication’ here is measured against whose yardstick? Pascoe himself complains about the Bradshaw rock art of Western Australia being attributed to non-Aboriginal people long ago on the basis of its style being that of a ‘more sophisticated people’ (pages 193–4). Yet in Dark Emu he seems very focused on stressing examples of the exceptional, the ingenious, the clever, the sophisticated, the most numerous, the oldest, the permanent.

The cluster of examples of ‘advancement’ that appear in Dark Emu are themselves not new. If you read widely enough, you are aware that they have been collected and made public before.

Just as an example, there is a haunting resemblance between Dark Emu and archaeologist Harry Allen’s 1980 contribution to a highly illustrated work created for the general public, The Aborigines of New South Wales. There, described in plain language and mostly illustrated with images, are a whole cluster of the same things that are presented by Pascoe in a revelatory framework: the gypsum mourning caps of widows (see above), claimed as some kind of precursor to pottery by Pascoe; the small ‘villages’ of grass-thatched huts (seasonally used); the Brewarrina fish traps (see below); the hunting and fishing nets (see overleaf); sewn skin cloaks; the ecological damage caused by introduced stock; and even explorer Major Thomas Mitchell’s 1835 report of ‘hayricks’ and ‘hay-cocks’ from seed gathering. Below I make available a swathe of similar introductory works of the past that make clear Pascoe is not breaking any truly new ground in relation to the economic, artefactual and technological facts presented.

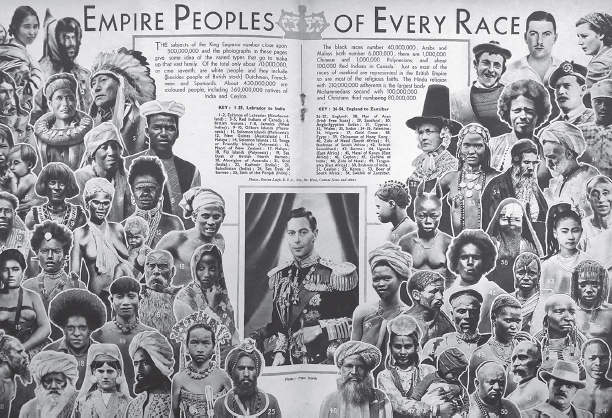

Three gypsum mourning caps.

Brewarrina fish traps.

Duck net, Murrumbidgee River, 1880s.

In the same 1980 volume as Allen’s essay, archaeologist Helen Clemens argued in a nuanced way against ‘mere hunter-gatherer’ descriptions:

Aborigines took measures to assist the growth or reproduction of animals and plants that were useful to them … In other words, whilst the Aborigines have in the past been denigrated for their primitive economy, it seems that in some areas they developed techniques that verged on agricultural practices, and in other areas deliberately refused to adopt such practices when there was no advantage to be gained.41

Another introductory text that includes the same cluster of topics— although balanced out with regional variations and combining the ordinary with the unusual—is Philip Clarke’s Where the Ancestors Walked.42 There we find a familiar cast of characters. There is the refutation of the same falsehoods that Dark Emu, eleven years later, identified: that the Old People did nothing beyond hunting and gathering and had a passive relation to their environment (Clarke’s pages 53, 62; page 65 is about fire management); that they wandered aimlessly over the landscape (page 53); that they did not store food (page 63); that they did not sew clothing (page 88); that they did not, at least seasonally, build substantial shelters (page 82); that they were constantly on the march and did not have periods of staying in one place (page 82). Clarke also describes (as Dark Emu does not) the predominantly ritual ways in which people ensured the reproduction of species (page 64).43

Pascoe is prone to finding a localised or regional exception to a general continent-wide pattern and then suggesting the exception was the norm. Briefly, we can point out here that in contrast to what he has suggested, the eel traps of western Victoria are unique in the whole country and the Brewarrina fish traps have no equal on the inland river systems. After a wide survey of Aboriginal weirs and fish traps, Worsnop referred to the Brewarrina trap complex as ‘a singular work of art’.44 The fish traps of the Glyde River (Northern Territory), much emphasised by Pascoe, were considerably more complex than other Aboriginal fish weirs set in flowing streams, and indeed were unique to only two clans of that river (see Chapter 8). These creations were complex, but they were atypical. A more balanced story is needed. Is there something wrong with the ordinary but effective?

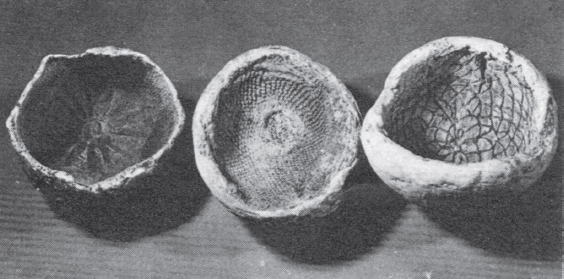

A common type of Aboriginal fish trap at the time of colonisation was the weir, sometimes referred to by English speakers as ‘dams’ even though they did not store water. Water and juvenile fish could pass through weirs, but not the bigger fish; and the bigger fish could then be readily speared without blocking the reproductive cycle of the species. In some cases, people combined weirs with nets, as in the Lake Eyre region (see below),45 or with a conical wicker trap, as in the photo below from near Nagalarramba, north-central Arnhem Land. The latter is a slightly unusual type given it worked with tides rather than in a stream. The diversion fence was many metres long.46

Remnant stakes used to divert fish to nets, Lake Eyre region.

Diversion fence with wicker fish trap, Arnhem Land, 1952.

Pascoe is not a trained anthropologist or archaeologist, and yet the issues at stake are complex and the relevant evidence from across the whole of Australia is voluminous. Much of it has been published in scientific journals or books written by social scientists, but much of it has also been published in introductory educational texts and even works for children. We use all of these in this book.

Pascoe has concentrated more on historical sources, especially explorers’ journals, than on the evidence of Aboriginal people who have traditional knowledge.47 In fact, there is almost no evidence in Dark Emu that he has asked Indigenous elders about their Old People’s economic practices. He does refer to his visiting the remote community of Lockhart River, CYP (page 70). Dark Emu also refers to Maningrida, which is in the Northern Territory (not ‘VIC’ as in the index; page 174). Nothing relating to local economic traditions is mentioned in Dark Emu as having been learned in either of these visits to remote communities.

Nor does Dark Emu draw significantly on works by specialist scholars who have studied Aboriginal traditional economics and material culture under senior Indigenous expert mentoring, often through a lifetime. We seek to compensate for this omission here by giving full recognition to the elders’ own knowledge of their people’s pasts.

As far as we can tell, no journalist or book reviewer covering the Dark Emu story has interviewed senior Aboriginal people from remote communities where knowledge of the old economy is retained at least by some, and practised in an adapted way by many. Nor do members of the media appear to have spoken to any of the anthropological specialists who have learned from Aboriginal authorities and from the vast literature on their traditional ways of life. The most obvious candidate there would have been Dr Ian Keen of the Australian National University, whose 2004 book is a thoroughly researched study of multiple regional Aboriginal economies on the threshold of conquest by the British Empire.48 He describes a rich array of cultural and economic practices, but does not find that mainland Indigenous Australians practised agriculture or gardening.

This journalistic abandonment of the academy, if that is what it is, seems to be symptomatic of a break from the past—a past in which professional knowledge and lay knowledge were more distinct, and the distinction more respected. The authority of the academy has slipped. Much worse than that, the authority of Aboriginal knowledge-holders has been ignored yet again.

Another problem in this case is that Pascoe’s heavy reliance on explorers’ journals is reliance on the evidence of those who encountered classical Aboriginal Australia only transiently at each location, and typically without any language in common with those they met. They were also the vanguard field agents of Aboriginal dispossession during the predatory expansion of the agrarian society of the British. They were men who were anxious to be able to map and report valuable future pastoral and agricultural environments back to Sydney and London. They were the forward scouts for the army of land-hungry farmers who would come in their wake. Waving fields of grass and stacks of seed-bearing stems, real as they were, could be easily read from a European standpoint as meadows in waiting, full of promise for the coming wave of agricultural usurpers.

We are not questioning the explorers’ immediate factual observations generally, but they cannot help us much with, for example, the question of how much the Old People relied on harvesting uncultivated natural resources versus those over which they exercised a degree of management, or how often they moved camp, or whether what the Britishers saw as a ‘village’ was there for temporary, medium or extended use. What colonials called ‘villages’ were probably temporary dwellings used seasonally, with the exception of places of longer stay in the minority of areas that can be described as unusually rich in resources and hosting the highest population densities: namely, the Western District of Victoria, the middle and lower Murray River, and the east coast of CYP north of the Stewart River. We discuss the evidence in Chapter 9 of this book.

In Dark Emu there is little or no reliance on the evidence of those who lived on the Aboriginal side of the frontier for months on end, learning from the traditional owners of the lands they lived in and learning local languages, as in the case of trained anthropologists such as Ursula McConnel, Donald Thomson, Fred Rose and Lauriston Sharp. There is also almost no reliance in Dark Emu on those early castaways who lived inside Australian Indigenous societies and operated in local languages, for years on end, as in the case of William Buckley (32 years), James Morrill (or Murrells; 17 years), James Davis (Duramboi; 13 years), John Sterry Baker (Boraltchou, 14 years) and Barbara Thomson (nearly five years). Pascoe makes one fleeting reference to castaway Narcisse Pelletier, who lived among Cape York people beyond the frontier, also for seventeen years, in the nineteenth century (page 70). These unusual sources had more to say that could have been useful to Pascoe—especially Buckley, who recorded so much detail about the movements and camping places of the bands he lived with in Victoria’s Western District (see Appendix 2).

Pascoe’s Dark Emu has been a print publishing and digital-media success, it has been rendered into dance performance by the famed Bangarra Dance Theatre, two children’s versions have been published, and it has begun to be incorporated into school curricula.49 It has many admirers—or perhaps one should say converts, given it is written in the style of dramatic revelation. It has been awarded two New South Wales Premier’s Literary Awards (Book of the Year and the Indigenous Writers’ Prize, 2016) and was shortlisted for the History Book Award in the Queensland Literary Awards (2014) and the Victorian Premier’s Award for Indigenous Writing (2014). Its offspring, Young Dark Emu, has won the Eve Pownall Children’s Book of the Year Award for Information Books (Children’s Book Council of Australia, 2020).

Noel Peemuggina and his student Peter Sutton, Ti Tree Outstation, Cape York Peninsula, 1977.

Pascoe’s book purports to be factual. It offers support for propositions in footnotes that lead to an extensive list of published and archival sources, and has an index.50 However, it is littered with unsourced material. It is poorly researched. It distorts and exaggerates many old sources. It selects evidence to suit the author’s opinions, and it ignores large bodies of information that do not support the author’s opinions. It contains a large number of factual errors, a range of which we analyse here. Others we could not include for want of space.

Dark Emu is actually not, properly considered, a work of scholarship. Its success as a narrative has been achieved in spite of its failure as an account of fact.

All of this success would appear to indicate, within our society and public sphere, either a profound lack of factual knowledge in relation to the peoples and history written about in Dark Emu, or an unconcern with facts and truth themselves, or a combination of these things. Whichever the case, the situation is troubling.