Archaeology aims to construct logical and impartial interpretations of sites and provide reliable methods for dating sites and objects. It is a discipline that bridges the sciences and the humanities and, from that bridge, scoops the waters of both to achieve its aims. It is far from easy to be on top of every relevant scientific analytical tool and to source every relevant and accessible document. For these reasons, comparison with other similar sites and/or objects is the ideal situation, alongside the use of multiple lines of testing and recovery of multiple sources of information, to produce a cogent and robust theory.

This chapter looks at the archaeological evidence provided in Dark Emu for Aboriginal agriculture and for a much longer occupation of the country by its first human inhabitants than is recognised by the scientific community.

Pascoe brings together two different types of Australian Aboriginal stone objects and a single bartered object under his category ‘Aboriginal agricultural implements’. It is an eclectic and somewhat sensitive selection of types that covers an exotic (non-Australian) hoe, a subset of picks, and the cylindro-conical and cornute (horn-shaped) stones known as ‘cylcons’. They are united by being ‘large and heavy’ (page 37). He writes:

These implements [‘hoes’] have received very little study since … (1894) … some commentators decided they were items of penis worship: the researchers assumed Aboriginal people too backward to have cultivated the land, so the stones have to have phallic significance ...

It is these implements [‘picks’] that are crucial to our understanding of Aboriginal agricultural history … The few that are labelled are tellingly referred to as Bogan River picks. [pages 36–7]

The first implement that Pascoe puts forward consists of just one example and was discussed here in Chapter 11. In summary, Robert Etheridge published a description of a stone implement traded into north Queensland from the Torres Strait that was described as ‘supposed to be a hoe’.1 Pascoe misquotes Etheridge and implies that the Torres Strait implement is of Australian Aboriginal origin. No other examples of this type have again been reported in Australia, and this one-off find is very interesting in terms of trade but of no further interest here.

Picks and cylcons have been described in a number of publications since the first by anthropologist Walter Harper in 1898.2 None of these papers classify picks or cylcons as ‘agricultural implements’. Pascoe argues that they have been deliberately misinterpreted or left unlabelled in order to avoid revealing their function. In fact, cylcons have been considered for over 100 years to be most likely of ceremonial purpose associated with increase or propagation ceremonies.3 Cylcons are concentrated in the Darling River valley, which is Barkindji country.

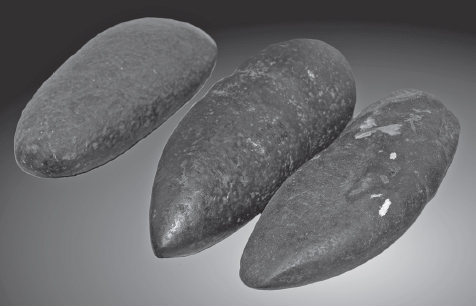

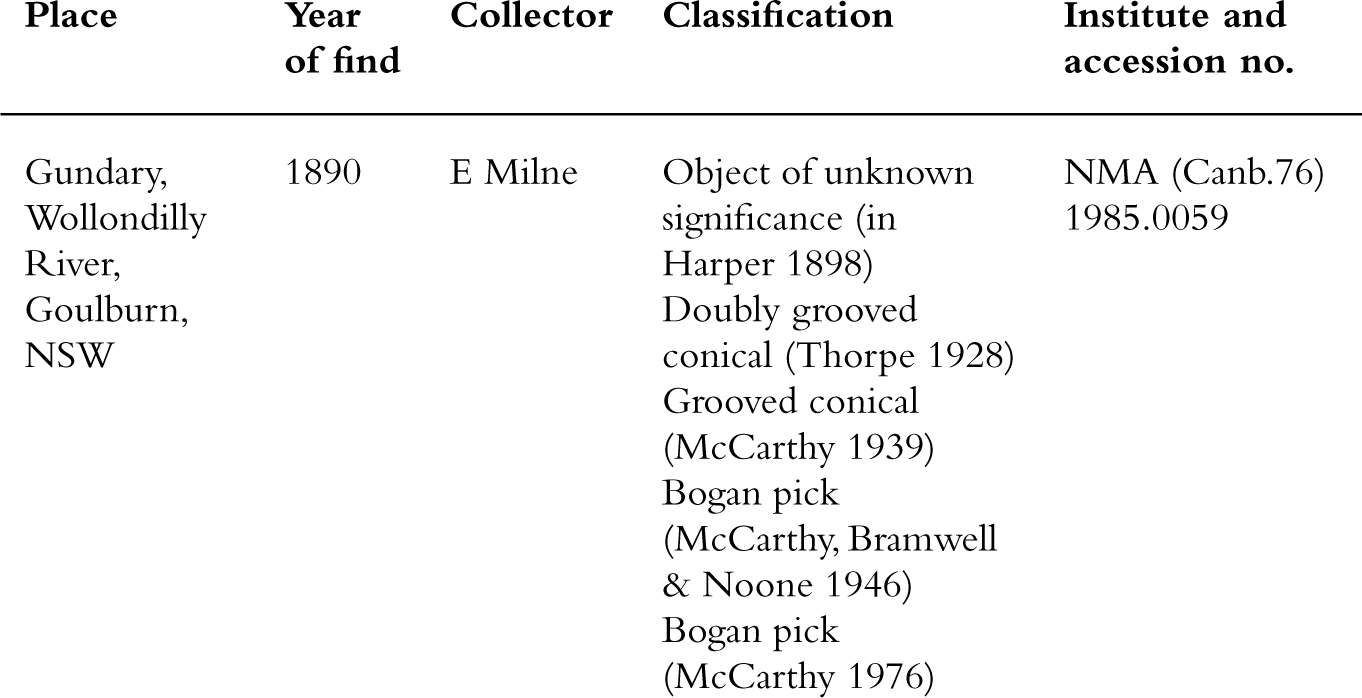

The other stone objects in Pascoe’s Aboriginal agricultural group are picks that have, over time, been known under various names, including Bogan River picks, Bogan picks, Bogan types, grooved picks and plain picks. These objects are concentrated in southern and central New South Wales. So far, eleven have been identified and described in museum collections.4 They are not associated with increase rites or propagation, nor have they been assigned phallic significance or known to have been associated with ‘penis worship’. Seven of them were recently displayed as Aboriginal agricultural implements in an exhibition held in South Australia,5 and photos of two are presented in Dark Emu.6

In 1888 an unusual stone was displayed at a meeting of the Linnean Society of New South Wales. It had been found at a depth of 7 feet (2.1 metres) while sinking a tank at Byrock, and was described as:

… of argillaceous [that is, clayey] sandstone, carrot-shaped, about 11½ × 2¼ inches [29 × 5.7 cm], the broad extremity concave, the surface marked transversely at intervals with lines of which there are five pairs on one side and three pairs on the other. Blackfellows to whom it had been shown could give no information about it; nor had anyone who had yet seen it been able to recognise its import.7

A similar object had been displayed during an earlier Linnean Society meeting held in 1884, and Harper decided to investigate the two unusual objects. While doing so, another seven similar stones were offered to him for inclusion in the study. The resulting publication was the first expansive overview of these ‘mystery’ stones, which were readily recognisable by their shape (cigar or carrot shape), size (25–60 centimetres), weight (2–3 kilograms) and unknown purpose.

Their surface is smooth and the cylindrical form tapers from a broad base to a conical end. The broad base is often concave with flaking, polishing and other abrasions, as if having been used for pounding and stood in sand. A smaller subset of items of ‘phacoid’ (lentil-like) shape8 were also called ‘stumpy’.9 But the real fascination lay in the decorative incisions around the body of some cylcons, which took the form of an emu or other bird foot, a boomerang, star shapes or lines.10

As to purpose, one theory proposed at the time was seed grinding. Harper dismissed this on the basis of the decorative incisions and the concavity, flaking and polishing visible around the base, all of which he saw as pointless for grinding. He also considered the ‘phallic emblem’ theory but concluded that:

This opinion, as far as I know, has nothing to recommend it except the shape of the ‘stones’ … the element of worship is entirely lacking … unless some better excuse for styling the stones’ phallic ‘emblems’ than that furnished by their shape can be found, we are not justified in considering them as such.11

Interestingly, he described one stone in his set of nine as seeming to have been used for ‘rubbing or grinding’—so much so that Dr Thomas Cooksey of the Australian Museum suggested that ‘the wear looked exactly like that noticeable on stones used for sharpening scythes’.12 However, Cooksey added that ‘probably some European had been using it for such a purpose’.13

Harper felt Cooksey’s theory to be entirely likely:

… it is evident the stone was never intended for a sharpening or grinding stone, because wherever the signs of the wear exist there all traces of the decorative marks have disappeared, and the originally smooth and rounded contour of the stone has been in a measure destroyed.14

Without evidence for grinding or as a phallic emblem, Harper leant towards ceremonial use (for increasing food production or rainmaking) and added that greater examination was required to settle the question.

Etheridge had access to a far larger collection (105) of ‘cylindroconical and cornute stones’ than Harper, but followed a similar line of inquiry by looking at the evidence for their use as a domestic, record-keeping, ceremonial or phallic item. As well as having many more specimens to analyse, he also had access to more information, and concluded that some cylcons were used as a grinder or pounder in domestic settings after the stone had been ‘adapted to a more casual purpose’.15 In regard to it being a record-keeping item, he felt there was ‘grave doubt’ as ‘so large a proportion … are absolutely plain and unincised’.16 He tentatively accepted two possibilities: ‘one indicating a phallic, the other a symbolic, tendency’.17

Etheridge’s tentative acceptance arose from three separate accounts given voluntarily by Aboriginal men and recorded after Harper’s investigations. The first occurred on Cooper Creek near Lake Eyre in 1901, during an expedition led by Professor JW Gregory, who:

… had with him as guide one ‘Emil’ … who on arriving in his own ‘country’ proceeded to dig up ‘a conical piece of yellow sandstone … and then presented it to me [Gregory], saying sadly that it would never be wanted again. He explained that it was a Wommagnaragnara, which, being interpreted, is “The heart of the snake”. It was used at ceremonies to make the dark olive-brown carpet snake, known to the natives as “Womma”, i.e., to increase the supply.’18

Etheridge emphasised that in this account, propagation is described ‘without in the slightest degree thereby implying any knowledge of phallic worship’.19 In other words, he echoed Harper’s conclusion in 1898 that there is no evidence to support phallic worship. Instead, the stones are suggested as symbolic of or used ritually in increase or propagation, and thereby are phallic in form only, not as an object of ‘worship’. In a similar vein, Etheridge cites RH Mathews, who had been told by an (unnamed) Aboriginal man that:

… they were ‘employed in ceremonial observances connected with the assembling of the people at the time the nardoo seed was ripe … in incantations for causing the supply of game and other food to increase, for making of rain, and other secret ceremonies … the stones … were kept by the headmen, or “doctors” … on the death of the owner they were hidden in ground near an old camping place of his, or else near his grave.’20

The third account considered by Etheridge in reaching his tentative conclusion had been relayed to Edmund Milne by an Aboriginal man named Tom Sullivan. Sullivan had implied that the stones were ceremonial objects belonging to ‘doctors’ or ‘medicine men’.21

These three separate accounts converge in suggesting that cylcons were related to increase ceremonies, were used by powerful men and were buried near campgrounds or graves. Etheridge found the cylindro-conical and cornute stones to be ‘the most interesting of all the Australian stone implements’ and concluded that ‘whilst the stones as a whole were almost certainly esoteric their application may have varied amongst different sections of the people using them’.22

The next expansive investigation of cylcons took place in the early 1940s and was undertaken by anthropologist Lindsay Black. Black also examined over 100 specimens, and he provided a detailed overview of each. However, he did not find any additional accounts or evidence beyond that previously cited by earlier researchers, and concluded that ‘cylcons were of ceremonial significance. Whether they were used at initiation, burial, Bora, or other kinds of ceremonies such as increase rites, will never be known’.23

Increase rites and their significance were also discussed in Chapter 2 of this book. Accounts provided directly by Aboriginal men all affirm the status of cylcons as an object used in increase rites. Increase is not ‘penis worship’, as stated by Pascoe (page 36)—a distinction made clear by Harper in 1898 and repeated thereafter.24

The specimens examined by Harper, Etheridge and Black are housed in the Australian Museum (AM) in Sydney. These and numerous other cylcons held in major collecting institutions across Australia have been the subject of ongoing inquiry over the past decade or so in order to ensure appropriate classification and access. They have not been on public display for some considerable time due to the sensitivity associated with their perceived functions as shown in the historical context.

While Black was investigating the ‘mystery’ stones of the Darling River in the 1940s, anthropologist and museum curator Frederick McCarthy was providing the first clear distinction between cylcons and non-ceremonial stones (picks) of similar shape and weight.25

Bruce Pascoe: ‘Jonathon Jones … asked to examine the stone tool collection at the Australian Museum, and there he found dozens of these implements … they have received so little study, most have never been displayed and almost all have no labels. The few that are labelled are tellingly referred to as Bogan River picks.’ [pages 36–7]

Jonathon Jones: ‘… often referred to as Bogan River picks … which were common along the rich Murray-Darling alluvial plains and are important for understanding Aboriginal agricultural [sic].’26

Lorena Allam: ‘… the Bogan River picks invite further inquiry: who made them, who wielded them, how and when? Some of the bigger implements are far too heavy to be used by a single person. Were they for cropping? We may never fully know.’27

As discussed above, cylcons (ceremonial stones) have been found in large numbers across a wide area of western New South Wales. By contrast, picks are concentrated in southern and central New South Wales with just one find outside of this area—in eastern Victoria.28 Some were collected off the ground while others were dug up by agricultural machinery. Formal picks held by museums number just eleven, and this appears to be the sum total in the nation’s institutional collections. There may of course be others held in private collections; however, it is unlikely that significantly more exist given the very few to have been found over the past 150 years. Two other picks are in the NMA collection, but they have not been expertly verified and no collection details are available.29

Picks were initially placed taxonomically with cylcons due to their similar form, weight and uncertain function.30 However, the absence of incisions, the flat rather than concave bases, and the presence on some of an encircling groove midway along the body kept them alongside, rather than within, the category of cylcons.31

McCarthy, with assistance from fellow anthropologist Elsie Bramwell and stone tool specialist Harold Noone, undertook the first systematic study of all known stone tool types in Australia. The resulting publication32 was built on similar but less expansive studies over the previous twenty years, including McCarthy’s own work.33 The study aimed to cover ‘function, shaping processes, form, transverse-section, and aboriginal names as criteria of classification of the Australian implements as a whole’.34

With the appearance of the first taxonomic sorting of Aboriginal stone implements, cylcons were placed under ‘Ritual implements’ while picks were placed within a subset of ‘Hunting and domestic’, which was itself incorporated under the larger category of ‘Miscellaneous implements’. This classification has not been changed in the two revisions of McCarthy and his colleagues’ original 1946 publication. Other publications, some more recent, do refer to picks, but the term ‘Bogan’ falls away.35

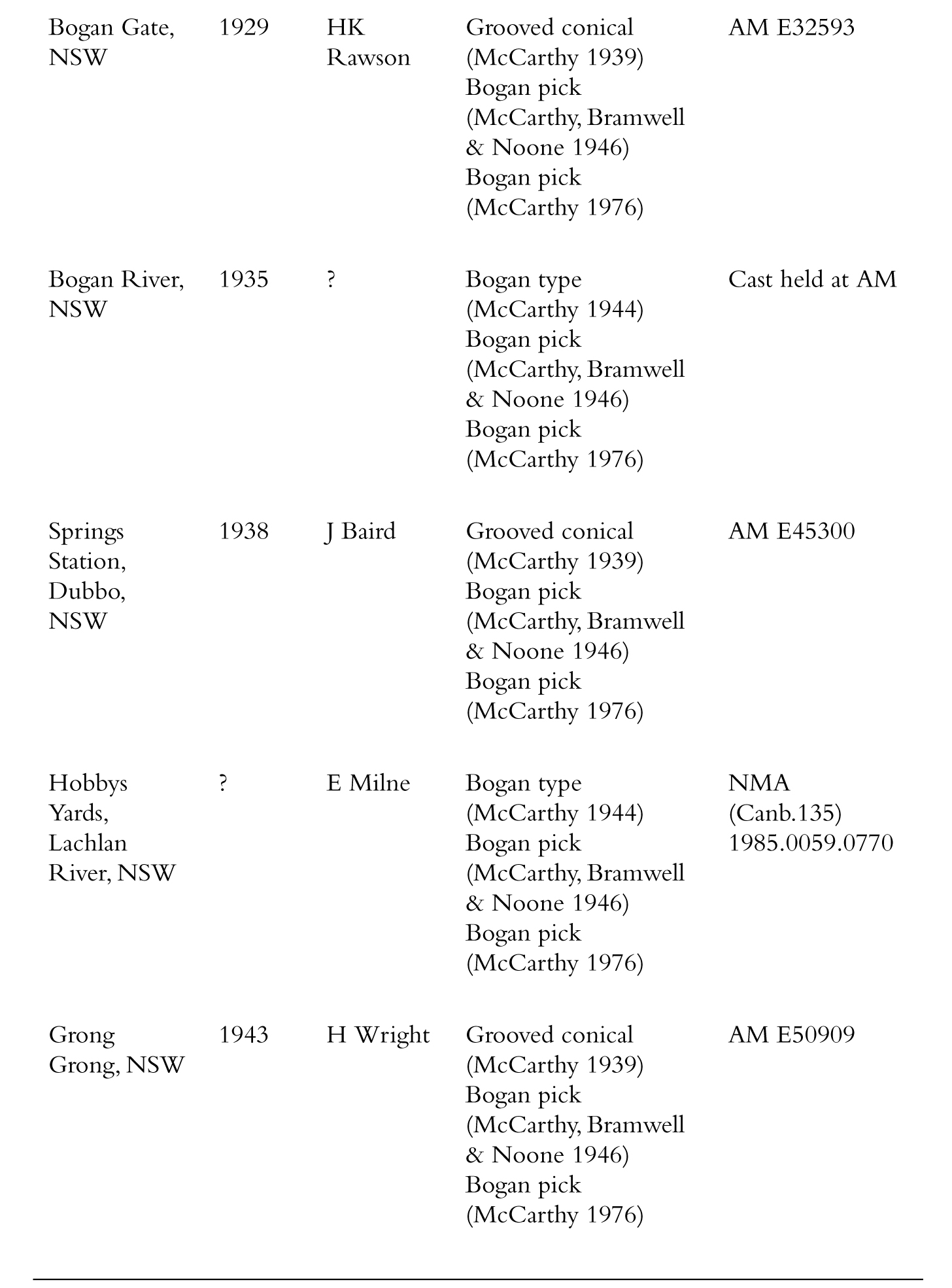

Under the classification of McCarthy and his colleagues, picks were divided into two groups: plain or Bogan-type, and grooved or conical type.36 The plain or Bogan type consists of three objects and the grooved or conical type consists of eight objects, thus giving the eleven mentioned earlier. If we add the two undescribed picks in the NMA collection, we have ten grooved (conical) types.

The standard pick is conical and measures about 15.5 centimetres in length, with a 10-millimetre diameter that is, in cross-section, oval or circular; picks can weigh up to 3 kilograms.37 One end of the conical form is blunt, the other tapering. The blunt end is similar to an adze end and is polished, while the broad end remains quite rough.38 Bogan picks and their encircling groove often show evidence of preparation by pounding with a hard stone (hammer-dressing) and polishing.39 The encircling groove is known as a ‘waist’ and one specimen has two of them, close together.40 The encircling groove (see opposite, which shows an example of the grooved conical type) was most likely for securing a bent cane, in similar fashion to hafting an axe handle to an axe head.41 In fact, the similarity to axes is apparent, apart from the adze-shaped end of a pick as opposed to the blunt end of a typical axe. This type of pick can use its weight to split apart dense wood with the haft positioning the head similarly to a stone axe head—that is, the striking end running parallel to the haft.

Grooved (Bogan style) picks.

Pascoe implies that the groove is the result of wear from binding a handle at right angles to the pick (page 36). This is incorrect given the hammer-dressing, and furthermore, bindings composed of soft materials would take an extraordinary length of time to wear such a groove.

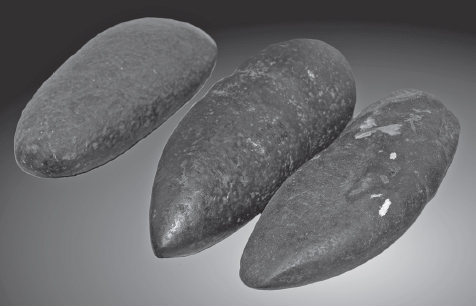

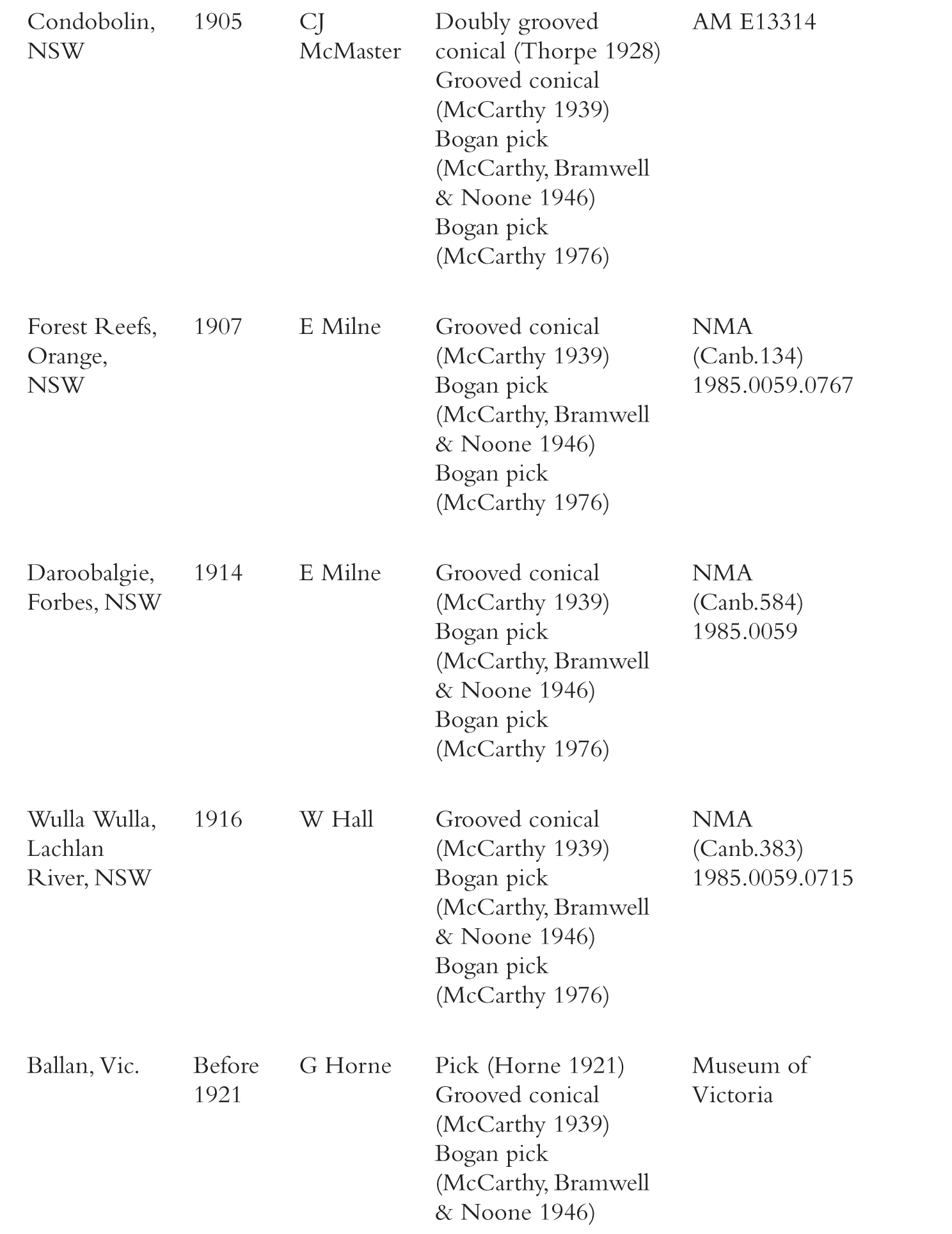

Given the few picks in collections, their history is well known, as presented in Table 9.

Table 9: Bogan picks formally identified and described.

Having so few specimens (thirteen at most) has restricted (or not inspired) research into the function of this type of pick. The specimen from Ballan, Victoria, was located deep inside a mature gum tree, giving rise to the possibility that it was used to extract possums.42 This would suggest a similar use to hafted axes, as mentioned above—for splitting dense wood to extract animals or to acquire timber for manufacturing wooden implements. The average weight of a pick (2–3 kilograms) is more than the average stone axe head, and it is possible that the picks were originally designed for splitting particularly dense wood localised to inland New South Wales. Perhaps at some time they were replaced by the lighter and more versatile stone axe.

‘Bogan River picks’ were a feature of a recent exhibition held at Adelaide’s Santos Museum of Economic Botany and the Art Gallery of South Australia. The exhibition was titled Bunha-bunhanga: Aboriginal Agriculture in the South-east and was curated by Jonathon Jones in collaboration with Bruce Pascoe and Bill Gammage. Bunha-bunhanga is a Wiradjuri word meaning ‘abundance of food’.43 The accompanying catalogue states that the exhibition ‘brings us primary evidence of our sophisticated agricultural past … For the first time in public, we see the heaving stone picks and slim shovels used to cultivate the murrnong fields …’44

Interestingly, explorer Thomas Mitchell witnessed wooden shovels in use along the Bogan River in 1835:

There is a small cichoraceous plant with a yellow flower, named Tao by the natives, which grows in the grassy places near the river, and on its root, the children chiefly subsist. As soon almost as they can walk, a little wooden shovel is put into their hands, and they learn thus early to pick about the ground for those roots and a few others, or to dig out larvae of ant-hills.45

From this observation, we get a sense of the shovels displayed in the Bunha-bunhanga exhibition as a tool for children to dig out tubers.

As discussed in Chapter 11, numerous colonial observations were made of Aboriginal people collecting murnong. In each case a wooden digging stick was observed in use rather than a ‘heaving stone pick’. Digging sticks are a wonderfully versatile tool, used not only to dig up tubers but also to dig out small mammals from their burrows and keep the camp dogs in order. They were ubiquitous across the country and appear in rock art. At any one point in time, thousands of them would have been in use across the country, such was their usefulness, ease of manufacture, portability and versatility.

In summary, the eight Bogan picks and three plain picks are the only described specimens in institutional collections. With their adze-shaped end and grooved midline for hafting, they were likely used in a similar way to stone axes. A bent cane was hafted along the groove to hold the axe head in place. With the substantial weight and density of stone, the adze end could break through timber to extract animals such as possums, and remove timber for working into wooden implements. Such a scenario was described on the Bogan River itself, by Mitchell in the early 1830s: ‘Unlike the natives on the Darling, these inhabitants of the banks of the Bogan subsist more on the opossum, kangaroo, and emu, than on the fish of their river.’46

Pascoe persists in claiming that explorer AC Gregory witnessed Aboriginal people harvesting grain with a type of stone tool, which he names as a ‘juan’ knife:

… many northern Australian museums display long, knife-like implements, which usually bear legends such as ‘of unknown use’ when, in fact, they are juan knives—long, sharp blades of stone with fur-covered handles, which the explorer Gregory described the Aboriginal people using to cut down the grain. [page 38]

… including the juan knives, which Gregory saw being used to harvest grain. [page 162]

Long-bladed stone tools, usually called ‘knives’, were often carried in a paperbark sheath or grip, as shown in the photo overleaf. The sheath worked to protect the edges of the knife from being damaged. McCarthy refers to juan knives ‘fitted with fur grips’ held in museums in Germany,47 suggesting an alternative to the more typical paper-bark sheaths. Juan ‘knives’ have been identified exclusively from a few excavation sites in central and western Queensland;48 none have been found in Western Australia, where Gregory made his explorations. They are similar to two other blade types, the elouera and the leilira, with all three being described as ‘trigonal knives’ (that is, they end in a triangle shape),49 hafted with gum resin at the butt end in order to create a handle. They are, more simply, a long-bladed stone tool.50

Long-bladed knife and paperbark sheath.

As with the geographically limited and rarely found Bogan River pick, Pascoe has selected evidence for harvesting by focusing on a tool that is geographically constrained and rarely reported. The juan knife was first described in 1957 by Norman Tindale in Queensland. The name was derived from the ‘Ngaun and kindred tribes’ who populated the area west of Charters Towers in western Queensland.51 An alternative name as suggested by Tindale was the ‘joan’. Archaeologist James Knight undertook a comprehensive analysis of a broken juan (or juin, as he prefers) knife found more recently near Charters Towers. At the time of his investigation a mere thirty-seven juan knives had been recorded and published.52 His analysis of thirty years ago remains the only in-depth investigation for this uncommon and geographically restricted object, and its status has not altered over that time. Based on the rarity of the juan knives, Knight suggests that it was a ‘prestige exchange’ object,53 leaving function of little or no regard beyond status.

Stone blades are one of the most common Aboriginal tools. They are used for cutting skin of both humans and animals but according to researchers Casey, Crawford and Wright are ‘not specialised in any way, and if found by themselves cannot be recognised, with the exception of those used as women’s knives, as having been intended for any particular purpose’.54 In some locations, blades are attached to spear shafts by use of gum and sinew.55 Spear blades, or points, survive on archaeological sites but the hafts do not, except in very rare circumstances.

Gregory’s original description referred only to ‘stone knives’, and made no mention of ‘juan knives’ or of cutting down grain.56 Gerritsen’s speculation that they ‘could be the mysterious juan knives’57 has been reimagined by Pascoe into a factual sighting by Gregory of juan knives with fur-covered handles. The fanciful nature of this becomes more notable in view of Gregory’s explorations heading far west or north showing the limited geographical distribution for juan knives.

In his attempts to link stone tools with agricultural production, Pascoe mentions another tool without any evidence: ‘the increase in production of adzes for sharpening wooden instruments such as digging sticks indicates a shift towards the more intensive cultivation of the yam daisy’ (page 162).

Adzes are part of a collection of smaller tools, thought to have increased in style and number about 5000 years ago.58 They were often hafted with a wooden handle, or set into an existing wooden tool such as a spearthrower, to make them easier to use (see below).

The daily toolkit of Aboriginal people was typically composed of wooden objects: digging sticks, spears, spearthrowers, clubs, hafted axes, hafted adzes, shields and boomerangs. The preparation and finishing of these objects led to countless adzes being discarded across the continent, every day over thousands of years. It is not sensible to build a statistical relationship between numbers of adzes and only one type of wooden tool, such as the digging stick.

Adze flake set in resin and hafted to wooden handle.

Pascoe suggests that the Hopkins River midden, located on a headland near Warrnambool in western Victoria, provides exceptional evidence for human occupation of Australia that is older by an extra 30,000 years or more than the currently accepted range, which is around 50,000 years (see Appendix 1):59

Western Victorian Aboriginal communities had been trying for thirty years to have an ancient midden on the Hopkins River analysed. It is so old, it has turned into rock. When that examination was finally undertaken, it was found that the midden was as old as 80,000 years, 10,000 years before the Out of Africa theory says humans began to leave Africa … It’s an interesting proposition to investigate for our understanding of all world peoples and their movements across the globe. [pages 40–1]

Middens are accumulations of marine or freshwater shells—essentially shell heaps—and have been a focal point for research in Australian (and global) archaeology for at least 100 years.60 The challenge for archaeology lies in distinguishing culturally formed shell heaps from naturally formed heaps.61 Apart from humans, wave action or seabirds can cause large deposits of shells and the distinction between these and cultural middens is not always clear.62 This archaeological question has gained greater resolution over time but is by no means completely resolved.

In the late 1970s Warrnambool local Jim Henry noticed a shell scatter near a headland then known as Point Ritchie, now Moyjil. Having an interest in natural history, he sought out Edmund Gill, a renowned scientist and former deputy director of the Museum of Victoria, who had recently retired to the area. Gill, along with Henry and other scientists, commenced investigations into the shell scatter in 1981. The first peer-reviewed paper discussing the site was published in 1988,63 which puts it at odds with Pascoe’s claim that western Victorian Aboriginal communities had been trying for thirty years to have the Hopkins River midden analysed. The paper reported a very ancient date for the midden. Problematically, the methodology used and the definition of the midden as cultural were not considered entirely reliable.64

Following the 1988 publication, other papers and postgraduate research theses focused the debate on how the midden was formed. The question remained over the shells being of cultural or natural origin (for example, bird behaviour). Seabirds, particularly the pacific gull, take shellfish from exposed rocks and reefs and break them open by dropping them while on the wing onto a hard beach platform below. Over many generations of seabirds using the same platform, the shells build up into ‘bird middens’—dense scatters of broken shell, very similar to middens of humanly discarded shell (for an example, see below).

Distinctions can be found in the narrower range of shellfish species taken by birds compared to those gathered by humans, who are able to forage more widely, use tools to extract shells tightly stuck to rocks, collect from deeper water, and select for size and taste. Looking for evidence of preferential shell size selection in the Moyjil midden, it was found that ‘The Lunella undulata [wavy periwinkle] shell opercula [feet] show clear evidence of size selection and we believe the deposit can be confidently labelled a midden [but] Whether humans or seabirds were responsible cannot be established confidently from the available evidence.’65

Midden left by seabirds breaking open shells for food.

With the lack of certainty in identifying birds or humans as the causal agent of the Moyjil midden, the team turned to other evidence. Cultural middens are also likely to contain stone tools, animal bone (particularly fish, reptile and bird) and charcoal from camp fires. The Moyjil midden did not reveal any of these, but it did reveal burned rock. The burned rock was speculated to be the result of wildfire or a camp fire deliberately lit by Aboriginal people—back to a natural versus cultural origin. Eminent geomorphologist Jim Bowler identified the burned rocks as definitively cultural in origin, and they became known as ‘feature CBS1’. It is this feature that was dated to far more than 80,000 years old, and, in fact, to a stunning 120,000 years old.66 However, archaeologist Ian McNiven stated that:

some evidence exists for CBS1 representing a ~120,000 year old hearth. However, the evidence for CBS1 as a hearth must be definitive and irrefutable for such a substantial claim to be considered credible, given the significant implications that this would have for world history. At this juncture, CBS1 does not meet this high level evidential threshold.67

Another scientist working on the site remarked that ‘Archaeological scepticism is heightened by the great antiquity of the shelly assemblage— beyond the accepted period of human occupation in Australia at 60–65ka [ka = 1000 years ago].’68

There is good reason for scepticism given the increasing number of scholarly reviews and commentaries questioning the dating of northern Australia’s ancient sites.69 In 2016, Wood and others provided solid data for limiting occupation across northern Australia to less than 50,000 years. More recently, investigation into environmental impacts on tropical sites provides good reason for caution while genomic sequencing provides compelling arguments as to why it is not possible for anatomically modern humans to have migrated to Australia any earlier than 50- to 55,000 years ago (see Appendix 1).70

The oldest reliably dated shell middens in Australia are about 30,000 years old71 but most are less than 10,000 years old, coinciding with stabilisation of the current shoreline. Exposed shell also has poor preservation, and it is only in exceptional circumstances that cultural middens are older than 10,000 years.

The six most recent publications devoted to the subject of the Moyjil midden at the time of writing72 agree that after thirty-plus years of dedicated research the question of the origin of the midden is not straightforward. At this point, we can conclude that shells and burned rock at Moyjil are significantly old—somewhere between 35,000 and 120,000 years—but not that Moyjil is an Indigenous cultural site.

In Dark Emu, Pascoe writes:

Rottnest Island, eighteen kilometres off the Western Australian coast from Fremantle, could be reached by land around 12,000 years ago. However, some of the artefacts currently under examination by archaeologists are reputed to be 60,000 years old. Ocean voyages must have been undertaken to reach the island under the lure of the enormous seafood resources. [pages 93–4]

In his more recent publication Salt: Selected Essays and Stories, the same sentences appear, except that ‘12,000 years ago’ has become ‘120,000 years ago’.73 Unfortunately, in both publications the comments are unreferenced, making it difficult to verify the source(s).

The reference to 60,000-year-old stone artefacts that are apparently still under examination by archaeologists appears to arise from two papers published more than two decades ago.74 In the early 1990s, three small stones, thought to be stone tools, were found in a deflation bowl (a hollow made by wind erosion) on the coastal margin of Rottnest Island.75 Two of the stones displayed typical features for small tools, but the third was less convincing—although because of its close spatial association with the other two, it was included in the final assessment.

These cultural items, the first ever identified on Rottnest Island, were hypothesised to be considerably old given their association with ancient soils revealed through wind erosion. No dateable material, such as charcoal, was found with the stones, but some years later a land snail shell, collected at the time, was dated. It provided what is a proxy date of 60,000 years:

The prehistoric artefacts and finds (3 stone tools in total) … do not provide absolute evidence for a human presence on Rottnest Island during the Late Pleistocene … these sites provide a significant addition to the archaeological and potential archaeological record for Rottnest Island and for Australia as a whole. They provide additional provisional evidence for Aboriginal occupation of Australia during the Late Pleistocene (>50 ka) …76

Although the paper in which this quote appears was published twenty years ago, the date of the snail shell remains provisional. Certifying an association between a proxy and an archaeological object or feature is not possible if no further or alternative evidence emerges. It is yet to be conclusively demonstrated that the land snail has anything to do with the three stones, and, in all, there is no evidence to argue for ancient ocean voyages between the mainland and Rottnest Island. Like many offshore islands around southern Australia, it was cut off from the mainland due to the sea-level rise following the end of the last glacial era—that is, 10,000–12,000 years ago.77

Apart from this residual uncertainty, the Rottnest Island stone tools themselves need to be reconsidered in light of other research into historic Aboriginal presence on offshore islands.78 After 1800, many Australian Aboriginal women involved in sealing and whaling operations off eastern and southern Australia left evidence of their presence on offshore islands, including Flinders and Kangaroo islands off South Australia.79 Kangaroo Island in particular has revealed numerous stone tools left by those working in the 1800s sealing industry, and many of these tools are associated with exposed, older soils.80 It is possible that the tools from Rottnest Island were left by Aboriginal people involved with the sealing and whaling industry.

When Dark Emu presents evidence from archaeological sites and objects, it is the caveats that go missing. As with any scientific reporting, caveats are critical for understanding the whole site context. When caveats are excluded from the discussion, the reader is grossly misled.

Other examples, such as Dark Emu’s claims for ‘kangaroo battues’ and ‘emu harvesting’, lack archaeological and archival evidence and are simply implausible. Archaeologist David Horton remarked some twenty years ago that ‘the concept of kangaroo farming keeps re-emerging at intervals …’81 He posed the question for himself in regard to the absence of such farming: ‘Given the Aboriginal practice of driving mobs of wallabies into enclosures in order to kill them, the step to permanently enclosing and maintaining such animals was, on the face of it, not a big one.’82 But in the end, he knew that:

There are some things about both the animals themselves and Aboriginal interaction that make this unlikely. Early stages of domestication probably involved keeping and raising young animals whose mothers were killed while hunting. This seems not to have happened in Australia. One reason may have been that the need for mobility meant that you didn’t want the added burden of carrying or being slowed down by young animals. Another reason may be that it is only worthwhile raising young animals if the effort results in a bigger return when they are mature. This is not intuitively obvious (and may indeed not be the case in Aboriginal circumstances), and in a hunting society you would be better off trying for a bigger animal the next day.83

Horton also raises an interesting question in regard to the absence of farming and agriculture in pre-colonial Australia. He presents farming as ‘addictive behaviour’,84 meaning that plants and animals become as reliant on humans as humans become on the few plants and animals that are domesticated: ‘Aborigines knew instinctively that there was no point in “conserving” individual animals: you had to conserve ecosystems. Farming wildlife was a process that a system established to maintain the Australian environment didn’t permit.’85

Dedicated, long-term and resilient conservation of ecosystems by Aboriginal hunter-gatherers for thousands of years has been discussed in Chapter 4 of this book. This is why Australia was in such good shape when Europeans arrived, and why it is has since undergone radical eco-instability.