‘[M]any Australians were surprised when Aboriginal women were featured at the 2006 Melbourne Commonwealth Games opening ceremony wearing magnificent possum skin cloaks. The pervasive idea’, writes Pascoe, ‘is that Aboriginal people wore nothing or animal skins’ (page 89).

That may be so. But the sentence that follows this looks like a very sweeping generalisation: ‘And they did wear skins but they were sewn, had sleeves for the accommodation of infant children, and could be used as rugs and bedding’ (page 89). The reader fresh to the subject would have to be forgiven for taking this to mean that most Aboriginal people wore clothes in the form of sewn animal skins. The fact is that many did but the majority did not. The regional differences were graphic. The authoritative map from 2005 (see page 3 of the picture section), designed for the general non-academic reader and widely available nine years before Dark Emu appeared, shows the distributions.1

But this is a seasonal map. Wearing a possum or kangaroo skin cloak in high summer would have been unbearable, at least during daytime. It follows that even in the regions where cloaks were worn, people were largely unclothed in hot weather. The northernmost record of a ‘possum skin rug’ is from the Townsville area in the 1850s or 1860s.2 In south-west Western Australia, people wore kangaroo skins rather than possum skins (see overleaf). In the Darling River region, Major Mitchell noted that prominent men wore skin cloaks during a ceremony while other men did not.3 The practice of clothing was not always just pragmatic.

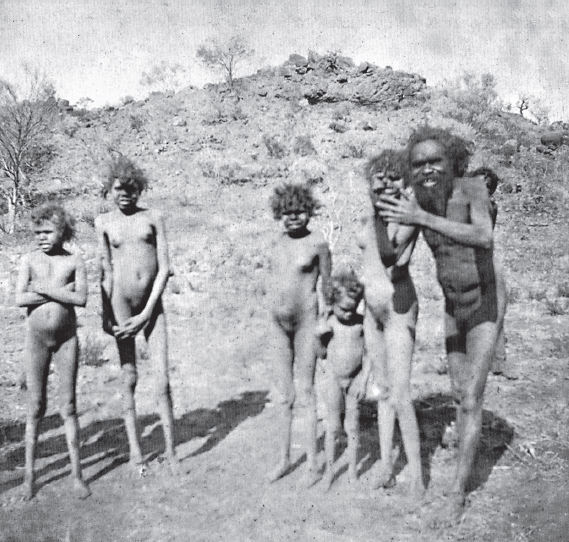

Men of south-west Western Australia, 1870s–1880s period.

Gender differences are widely reported in the use of body coverings. For example, writing of the Western District of Victoria in the nineteenth century, a region with a bracing winter climate and where people certainly did sew possum skins to make cloaks and rugs, James Dawson said:

During all seasons of the year both sexes walk about very scantily clothed. In warm weather the men wear no covering during the day time except a short apron, not unlike the sporran of the Scotch Highlanders, formed of strips of opossum skin with the fur on, hanging from a skin belt in two bunches, one in front and the other behind. In winter they add a large kangaroo skin, fur side inwards, which hangs over the shoulder and down the back like a mantle or short cloak …

Women use the opossum rug at all times, by day as a covering for the back and shoulders, and in cold nights as a blanket … A girdle or short kilt of the neck feathers of the emu, tied in little bunches to a skin cord, is fastened around the loins.4

William Buckley recorded that when women of the Colac/Indented Head region of Victoria engaged in fighting, or in ceremonies where they used their ‘rugs’ as musical instruments (for pounding the beat), they went naked.5 There is no record of which I am aware that the skin cloaks of the colder regions were worn over any kind of undergarment.6 There is an early record of a skin cloak being worn under circular rush mats by a woman Mitchell and his party met in the area of the Glenelg River, south-western Victoria, in 1836 (see below). The first people Narcisse Pelletier encountered after surviving shipwreck in the Cape York Peninsula in 1858 were ‘three women, who were entirely naked’,7 but he also described women wearing ‘a fringe of cords extending from the waist to half way down the thigh’.8

Mitchell’s ‘Female and child of Australia Felix’.

Sandals were used to walk on superheated or extremely prickly ground rather than worn all year round, but are reported only from some regions.9 One should not underestimate the toughness and ability to weather discomfort that traditional people enjoyed.

The regionally differing spectrum of items worn on the body in 1788 was in fact very large. In their introductory text referred to elsewhere here, the Berndts gave a brief but wide-reaching summary of this variation.10 A generation or two of students and interested lay readers would have been exposed to this survey, given the book remained in print for over thirty years.

Skin cloaks and the paperbark aprons unique to Tiwi women11 (see below) are at the maximal covering end of the spectrum. In other regions people usually were more lightly clad, including those regions where people were largely unclothed, even in very cold weather. By ‘largely unclothed’ I refer to the very common pattern whereby different people wore a pubic tassel, or a hair belt, a headband, a pearl-shell pendant, bracelets and necklaces and other adornments, but no general skin covering.12

Tiwi women and girls wearing traditional paperbark aprons, Bathurst island, 1913.

A Kimberley example comes from Rev. JRB Love, who was a missionary there from 1927 to 1940:13 ‘Except for the pubic tassel worn by the younger women and growing children the Wo’rora roam the bush completely naked.’14 He failed here to mention the substantial hair belts worn in the same region, but described them elsewhere.15 There are hundreds of published photographs from colonial and later days, on the edge of the advancing imperial frontier, showing people in many different degrees of covering and adornment, from being fully swathed in sewn possum skin cloaks to being fully naked (see below).16

People were not prudish about nudity but valued modesty, expressed in sitting positions and in averting the gaze, for example. An early record of this etiquette is from First Fleet member David Collins at Port Jackson: ‘… and although entire strangers to the comforts and conveniences of clothing, yet they sought with a native modesty to conceal by attitude what the want of covering would otherwise have revealed’.17 Elsewhere Collins recorded for the Port Jackson area the possum-fur string apron worn by girls until married.18 A more nuanced account based on deep anthropological field work from 1927 to 1934 among the Wik people of Cape York Peninsula comes from Ursula McConnel (see below and opposite, top):

Clothes in the European sense are non-existent. Men and women go naked. Aprons are worn by women only on certain occasions with a special significance. A young girl … first wears an apron when she returns to camp after separation at the onset of puberty [menarche], and after each ensuing separation for a similar reason [menses], either as a mature girl … or as a married woman … When a mother returns to her husband’s camp at the end of her isolation during childbirth, she wears a brand new apron … Aprons are also worn by women on ceremonial occasions, as when they take part in dances, and especially for the mourning dance.19

Man with two wives and children, Tomkinson Ranges, 1903.

Wik girl on plains south of Aurukun, western Cape York Peninsula, 1927.

Wik women performing mourning dance, western Cape York Peninsula, 1927.

Omitted there by McConnel were the grass skirts worn by men during certain ceremonies (see below). She also omitted the ‘women’s utility pad’ made of paperbark which was used when a woman had her period, or to prevent penetration by leeches while extracting tubers or corms in swamps.20

Wik men in ceremony, western Cape York Peninsula, 1927.

What is most impressive about classical Wik adornments of the body is that, perhaps with the utility pad as a sole exception, all of them are symbolic statements rather than primarily a means of comfort or covering. Women’s aprons mark certain distinctive states—developmental stage, post-partum condition, ritual performance. Similarly, people wore, at different times, these: healing and protective strings tied around the affected body part; strings while hunting (worn by men); strings while diving for waterlilies (worn by pregnant women); shell nosepegs; pearl-shell pendants; necklaces and headbands; pandanus armlets (men); large wooden ear-cylinders in the lobe (men); a collar of wood studded with red beads (men); cowrie shell girdles and crossovers (women); mourning strings (women); mourning necklets (women); a woven betrothal ring; lover’s strings; and umbilical-cord pendants.21 Embellishment outranked ‘clothing’.