A conference titled ‘Man the Hunter’ was held in 1966 in the United States and generated enormous interest for its challenge to orthodox views on hunter-gatherers. It inspired new methodologies as well as revisionist feminist responses,1 and the proceedings, published in 1968, were soon followed by an impactful work titled Stone Age Economics.2 Fieldwork on hunter-gatherers during the 1960s and 1970s gathered a range of case studies sufficient to upset the social evolutionary view of hunter-gatherer life as in all ways inferior to that of the farmer. Scholars could no longer unquestioningly perpetuate the view that the emergence of agriculture had involved ‘progression from the hardship of the hunter’s lonely, nomadic and hungry life to one of security and sociability’.3

With the release of Man the Hunter and Stone Age Economics, farming as a progressive and inevitable step up from hunter-gathering was no longer immutable. Slightly earlier in Australia, anthropologist and Museum of Victoria curator Aldo Massola had voiced similar sentiments:

The fact that … Aborigines were nomadic food gatherers does not mean that they wandered aimlessly all over their tribal territory in the hope of finding food. On the contrary, knowing every inch of their country they would spend the different seasons at the most fruitful places. These would mostly be located in the vicinity of water, and in some places water fowl, fish and roots from aquatic plants would be so abundant as almost to obviate the need to wander to new grounds. Such a place was Lake Condah.4

Of some importance to Pascoe is Lake Condah in the Western District of Victoria, which has been studied geologically, hydrologically, ecologically and archaeologically. It is via the latter discipline that Pascoe finds evidence for high populations of people living in large aggregations of stone houses in order to harvest, smoke and cache thousands of eels annually in that location.

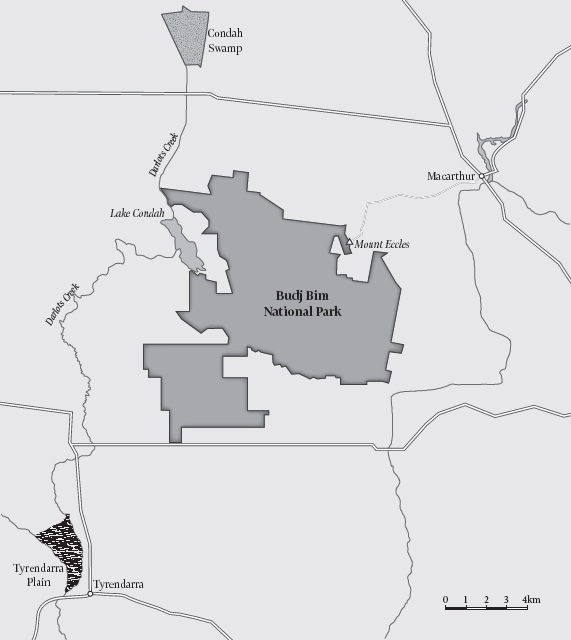

This chapter focuses on the archaeological evidence for settlement and aquaculture at Lake Condah—that is, the aggregations of stone houses and smoking and caching of eels—prior to European arrival. Important to this discussion is an understanding of the naturally formed lava-flow plain that provides the context for the Budj Bim fish trap complex (see below).

Map of Lake Condah region, western victoria.

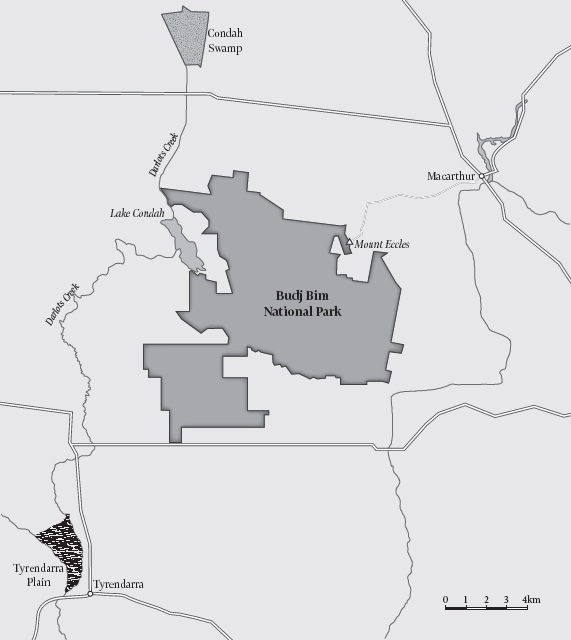

Detail of part of Lake Condah fish and eel trap.

Budj Bim (Mount Eccles) is the principal volcanic vent amid a series of numerous minor vents in western Victoria. This volcanic system was last active about 9000 years ago, with a major eruption much earlier, about 37,000 years ago,5 causing a massive lava flow across the preexisting drainage plain.6 As the lava cooled, a series of swamps, shallow lakes and narrow channels formed on a very flat plain.7

This flat plain was further eroded by wind and rain over the ensuing millennia. However, a slight tilt to the south-west enabled water to flow along naturally formed ancient river channels to reach the Southern Ocean.8 This complex hydrological system of swamps, lakes, creeks, rivers and the ocean provides the perfect conditions for migratory fish to achieve maturation and cyclical spawning by alternating between fresh and salt water.9 In other words, fish can spend time in or away from the ocean by migrating along naturally formed channels, according to their physiological needs.

The most common species of migratory fish known to exist in western Victoria are short-finned eels (Anguilla australis) and mountain trout (Galaxia spp.).10 Lake Condah and Condah Swamp are significant places along this complex hydrological system. In times of low rainfall, they are reduced to a series of muddy-bottomed puddles and waterholes. At these times, short-finned eels survive by burying themselves in the mud or traversing open ground to find a more tolerable refuge. In contrast, heavy rainfall initiates currents in streams, creeks and rivers, and the current in turn initiates migration for both short-finned eels and mountain trout.

Eels and trout inhabiting the naturally formed system of connected swamps, lakes, creeks and rivers on the lava plain of Budj Bim annually reach or leave the Southern Ocean. As Massola observed in the 1950s and 1960s,11 Aboriginal people advantageously used their deep ecological knowledge of a vast array of natural and cyclical events in order to maximise their fish catch. Since at least 6000 years ago this naturally formed system has been deliberately modified by Aboriginal people building stone structures replete with brush fencing and woven baskets in order to trap migratory fish.12 The trapping activity was closely observed and in most cases documented in the 1800s by explorers, missionaries, settlers and wanderers alike. These records have since been much referred to by archaeologists and anthropologists.13

Aldo Massola’s public address to the Royal Historical Society of Victoria in June 1962 referred to observations and sketches from the mid to late 1800s of Aboriginal people operating fish traps in western Victoria.14 In 1973, Harry Lourandos relocated a fish trap at Toolondo (in western Victoria) by referring to the 1800s journals of George Augustus Robinson and James Dawson.15 Peter Coutts was investigating Aboriginal mound sites in the area at that time16 and, inspired by Lourandos’ success in using the early journals, he headed to Lake Condah. During 1975 Coutts, along with Rudy Frank and Philip Hughes, located and undertook an extensive survey of the Lake Condah system.

Of the system, Pascoe wrote: ‘The channels looked like human-made structures, but experts couldn’t believe they would work hydrologically’ (page 83) and ‘Local Aboriginal people were not credited with sufficient knowledge of engineering or energy to have created them’ (page 84).

In fact, Coutts and his team were impressed by the scale of the trap, which was clearly designed by Aboriginal people to capitalise on migratory fish as they moved between fresh and saline waters:

Our surveys suggest that there are four major systems of fishtraps, each of which comprises several stone races, canals, traps and walls which are articulated, either by accident or by design. The route of each stone race and canal has been carefully chosen to take full advantage of the natural topography, generally following drainage lines.17

Coutts was also, at that time, the director of the Victoria Archaeological Survey (VAS), and over the next decade or so he led numerous archaeological surveys in the Lake Condah environs. Archaeological surveys across western Victoria from 1973 onwards resulted in hundreds of cultural sites being placed on the record. Pascoe takes a dim view of this survey work on fish-trap sites, referring to ‘the rather desultory examination of them by the Victorian Archaeological Survey’ (page 78) and remarking that ‘many [of the sites] have been destroyed by agriculture and rock collection for fencing, commercial purposes, and home gardens …’ (page 78).18

Certainly, many heritage features across western Victoria have been impacted or destroyed by the activities named here by Pascoe. The same destructive activities were identified in the late 1980s during a regional cultural heritage survey and conservation assessment instigated by VAS.19 This assessment also identified drainage works as a major destructive activity. Such works commenced on a minor scale with the establishment of Lake Condah Mission in the 1860s, but were dramatically scaled up in the early 1900s to appease local pastoralists complaining of seasonal flooding in Condah Swamp. The natural ecology of the lake and adjoining swamps, as well as heritage features, were significantly impacted by the drainage works.

Regardless of the destructive activities operating in the first half of the twentieth century, by 1990 over 200 stone circles, and numerous fish-trap arrangements, had populated the heritage database for the region.20 The stone circles are roughly circular in shape, as their name suggests; they are 1–2 metres in diameter and each has one or two courses (layers) of stone.21 Coutts recorded them ‘scattered throughout the area, in groups, individually and adjacent to fish traps’ and interpreted them as the base for a ‘stone house’.22 Pascoe suggests that construction was allotted to fabled others: ‘The structures … looked like small round houses, but all sorts of speculation on their origins abounded, including conjecture that survivors of the fabled Mahogany ship … had built the systems’ (pages 83–4).

As depicted in the various ethnographies, the frame posts for huts in this region could not be positioned directly in the ground due to the hardness of the lava plain. Instead, timber frames were held in place using stones. The ethnographic depictions were a powerful influence and Coutts saw no alternative for the stone circles other than being the bases for dwellings.

Western Victoria is pivotal to Pascoe’s argument for large sedentary populations aggregated into villages. Stone circles are critical to population estimates and to interpreting housing arrangements. Coutts and, later, Pascoe used them to estimate the population of western Victoria: ‘So, if they were houses, and if the channels were a fishing system, then around 10,000 people lived a more or less sedentary life in this town’ (page 84).

By the late 1970s, Coutts thought that perhaps 200 people aggregated temporarily around Lake Condah:

Certain areas may have been temporarily occupied by large aggregations of Aboriginals (for example up to 200 or more people) for the purpose of eeling. During other times of the year, group sizes were almost certainly smaller and of a semi-sedentary nature, as the Aboriginals exploited other food sources including freshwater fish, daisy yam and marine resources.23

A few years later and perhaps for the benefit of an interested news media, Coutts offered a village scenario with a far larger population:

Living in a small stone house in a village of similar houses … It’s a far cry from the traditional picture of the Australian Aborigine as a nomadic hunter and food gatherer with his spear … There are more than 140 house sites and we keep discovering more … They are situated in an area rich in food resources—and they are associated with bird hunting and fishing … In one paddock there are 146 houses. If most of them were occupied by one family that makes a population of 700—in one paddock alone.24

This unusual scenario of prolonged settlement and intensive subsistence in a particular area had been hypothesised a little earlier by Harry Lourandos,25 who twenty years later summarised his thinking as ‘high population density, semi-sedentism and complex economy and social relations … could be explained not only by the high bioproductivity of the area but also by the development of these features through time …’26

Both Lourandos and Coutts recognised that the unique natural endowments of western Victoria’s lava plain provided a premium habitat for migratory fish and that in response, Aboriginal people developed elaborate trapping systems that were built in the knowledge of the natural flow regime and migratory fish habits. For this reason, hunter-gatherers were able to remain for unusually long periods in the region. Archaeologically, this was expressed in high numbers and types of cultural stone features.

Coutts estimated at least 700 people around Lake Condah, based on the number of recorded dwellings and using an average of five people per dwelling. Pascoe estimates 10,000 people by presumably applying an average of fifty or more people per dwelling:27

Early reports from settlers and colonial administrators such as [GA] Robinson refer to buildings where over fifty people gathered, but the most common size was a dome three to five metres across and two metres high. As a family had more children extra rooms were added or the larger structures underwent subdivision by internal walls. [pages 128–9]

With an average diameter of 1–2 metres per base, fifty people is quite a crowd. However, the important point is not how many people can occupy a small rounded dwelling but the interpretation of stone circles. The trend set by Coutts in the 1980s meant that every stone circle was indiscriminately recorded as a ‘stone house’.

By 1990, it was recognised that possible overenthusiasm (in the form of archaeology summer schools), rather than ‘desultoriness’, had led to a lack of rigour in site recording. In response, VAS engaged an independent archaeologist to undertake ‘collation and field checking of all known sites and the documentation of previously unrecorded sites … as an essential contribution to the future planning and management of the Study Area’.28

The study area was principally Lake Condah and the archaeologist was Anne Clarke. She found that terms such as ‘stone house’, ‘hut’ and ‘village’ had been loosely applied without a clear and consistent definition.29 The vision of ‘hundreds of people living in villages’ had gone unquestioned and become all-pervasive, as witnessed in a former diorama at the Museum of Victoria that depicted a scene at Lake Condah with the caption: ‘The Kerrup-Jmara did not need to move house, and their villages of stone were probably permanent. Several hundred people lived in some villages.’30 This exhibit was complemented by educational resources designed by VAS, conveying the same image of permanent stone houses set out in villages.31

In order to truly appreciate the complexity and diversity of the Lake Condah stone arrangements, it is critical to distinguish between different site types. If some stone circles were not house bases,then additional functions and purposes for stone features at Lake Condah were being overlooked. Clarke spent four months in the study area, inspecting and confirming the location of every recorded stone circle and logging stone circles not previously recorded. She was assisted in the field by Linda Saunders and Christina Saunders, Aboriginal traditional owners from Portland, and by archaeologist Giles Hamm. The final report was completed in conjunction with the Kerrup Jmara Elders Aboriginal Corporation.32 Kerrup Jmara is a subgroup of the Gunditjmara people. It was therefore mistaken of Pascoe to refer to ‘the local Gundidjmara people, who knew all along what the structures represented, but whose opinion had never been sought’ (page 85).33

Clarke focused on establishing robust criteria for distinguishing natural from cultural processes that result in stone circles. Distinguishing natural from cultural phenomena is very familiar ground for archaeologists, and fundamental in generating reliable and robust heritage registers. In regard to possible processes leading to the formation of stone circles, Clarke listed geological and post-lava-flow landscape processes as natural, and Aboriginal construction and European landscape modification as cultural.34 Examples of natural formations included the edges of sinkholes and lava tubes; cultural examples included such things as hunting hides, blinds and windbreaks. Any of these processes can make stone circles out of the basalt rock that was left strewn about by various volcanic events. There can also be some degree of overlap between, or mimicking of, cultural and natural processes, and Lake Condah proved no exception.

Geologist Neville Rosengren was engaged by VAS to provide further assistance in the field surveys. He identified natural processes capable of forming stone circles indistinguishable from cultural circles—such as ‘pahoehoe’, or lava that ‘is also a process capable of forming circular accumulations.35 The greater mobility of lava that forms pahoehoe surfaces gives rise therefore to several mechanisms by which circular stone accumulation may occur’,36 and ‘given the nature of the volcanism at Mount Eccles that provided the lava for Lake Condah, it is possible to develop hypotheses that would explain circular structures developing and persisting there’.37 But in the end, he felt there was a degree of uncertainty in making definitive statements: ‘Although there is no strong evidence of volcanic or other “natural” origin of the rock piles, more precise evaluation can be determined by further field research …’38

Rosengren went on to list five essential points for further field research, emphasising morphological analysis, particularly the relationship of the stone circles to the underlying lava surface. In other words, it was imperative to know if the stones forming the circles were clearly separate from the ground surface. But the continuity or attachment of the upper layer of fractured basalt blocks to the fissured lava field could not be adequately inspected due to dense vegetation cover.39 This was also apparent to Clarke, who commented that ‘The problem of trying to establish clear criteria for distinguishing Aboriginal stone circles was never satisfactorily resolved during the field season.’40

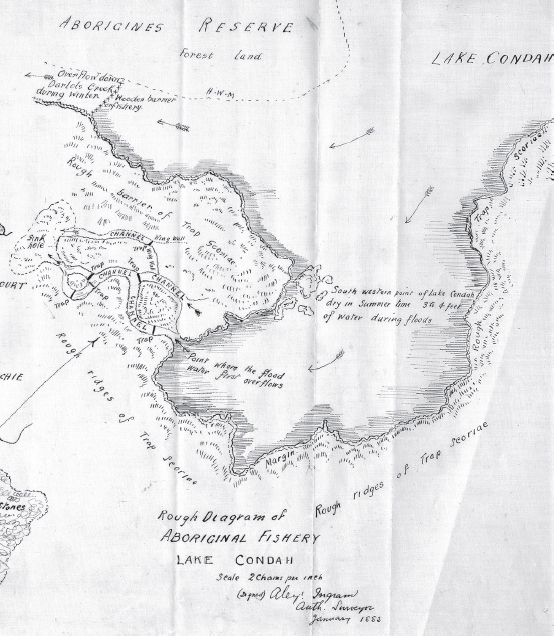

Another phenomenon identified by Clarke, and one that also forms a stone circle, is a tree falling over. Trees growing on the basaltic plain have their roots intermeshed with basalt stones, and on heaving over, pull up the stones held tightly in the root mass (see opposite). Clarke examined a place where a tree had recently heaved over, leaving a stone circle that she described as ‘one or two courses high, with the basalt blocks resting at a range of different angles, mimicking the pattern expected if people were collecting blocks and making circular shelters. If the tree falls over this also creates a break in the circle making an “entrance”.’41 Living trees can also bring up stones from around the base as their girth expands. Once the tree dies and rots away this, too, leaves a circle of stones.

Rocks held in root mass of fallen tree.

At the end of the fieldwork, Clarke had field-checked 173 previously recorded stone circles and recorded 92 new stone circles, resulting in:

a resource inventory comprising accurate mapping of the sites on aerial photographs and maps, preparation of a record form for each site, a site gazetteer and a report. The project also posed new questions about the way some site types may have been formed, and made preliminary comments on the integrity and management requirements for the sites.42

The VAS database, having commenced with 226 Aboriginal cultural sites in 1990, rose to 318 with the 92 new records, before dropping to 265 with the removal of 53 records that could not be verified as cultural sites.43 The result was a more reliable database, reflecting greater site integrity. It was also larger than it had been prior to the 1990–91 survey commencing. Yet Dark Emu erroneously claims that ‘The Victorian Archaeological Survey examined stone arrangements at Lake Condah in the late 1990s, and declared that they couldn’t be house sites’ (page 83).

If the cultural stone circles had revealed cultural artefacts, such as stone tools, shell, animal bone, ash or charcoal, and the natural stone circles were sterile, then it would have simplified matters. Instead, and interestingly, of the 318 cultural and natural stone features recorded in the region, only one circle was recorded with artefacts. It was excavated, and its charcoal samples returned a date of less than 200 years old, which was fitting with the glass identified on the same site.44 Speculation arose that some stone circles represented huts built by Indigenous people post-European settlement in order to avoid direct conflict. A second stone circle was recently identified with stone and glass artefacts and also returned a modern date, of circa 1950s.45

Archaeology in Australia has witnessed many drawn-out debates over nature versus culture, and the stone circles at Lake Condah was one debate that has rolled on into the twenty-first century and brought with it a new level of interpretation.

Heather Builth commenced fieldwork south of Lake Condah in the late 1990s to find evidence for the premise that ‘complex fisher-huntergatherers’ (as she termed Aboriginal people in western Victoria) became sedentary by virtue of evolving a highly specialised technological innovation around food supply, storage and distribution.46 This, she believed, led in turn to hereditary chiefdoms,47 which denied the ‘prevailing anthropological perspectives of Aboriginal primitivism, [and] resulted in the acceptance of pre-contact Aboriginal people as struggling to survive within a hostile environment’.48

In other words, Builth believed that at the end of the twentieth century, the prevailing anthropological view of Aboriginal people was still that of a population locked in a perennial battle with a hostile environment over which they had no agency. The falsehood of this view has been discussed earlier in this chapter, and in Chapter 3, where clearly it was very much taken to task from the 1960s onwards by anthropologists, and long before Builth began her research.

Identifying hereditary chiefdoms is a popular theme in anthropology, but it is outside of what is intrinsic to the archaeological exploration here. Instead, the prime interest here is that Builth links highly specialised technology (food supply, storage and distribution) with human emancipation from natural whimsies—that is, she equates personal agency with having control over nature. Finding technological evidence for controlling the supply, storage and distribution of food became the key focus of her research. Pascoe writes:

Builth … knew that only science could convince the doubters … and found that human agency was the only thing that could have produced such complexity. So, if they were houses, and if the channels were a fishing system, then around 10,000 people lived a more or less sedentary life in this town … If, she wondered, such a large population lived there, the demand for food would be extreme. There had to be some form of food preservation associated with this town.49 [page 84]

As Pascoe states, Builth was keen to demonstrate complexity in food preservation as this would provide evidence for large, sedentary populations and thus set the scene for those hereditary chiefdoms. At first she focused on the stone circles; later she included mature trees in her field surveys. Inevitably she had to revisit the natural-versus-cultural stone circle origin debate, including the work of Rosengren. She wrote: ‘Rosengren concluded that geological processes do not account for an obvious misidentification of natural features of [sic: or] cultural features.’50 This comment by Builth is not particularly clear, but a comment by Rosengren is:

The lava thus developed a highly irregular outline in plan and a rough and broken surface. Some of the stone arrangements which are the subject of archaeological interest could possibly be natural features resulting from this period of lava surface formation.51

Rosengren had also commented in his report that the lack of excavation or disturbance of any stone features prevented ‘the opportunity to evaluate the relationship of stone blocks with the underlying lava surface and [made] it impossible to confidently assert as to the nature of the arrangement or movement of the overlying material’.52 However, convinced that there was no geological interpretation for stone circles having formed, Builth claimed just two possible origins—humans or tree heaves (falls).

Pascoe wrote: ‘She weighed and measured each stone in the house-like structures …’ (page 84). Not exactly. Builth elected to weigh and measure stones from one stone circle and the visible stones from around one tree heave.53 The metrical analysis revealed that stones taken from the stone circle fell within ‘a relatively limited range which are relatively easy for an individual to move’.54 In contrast, stones from the tree heave did not conform to a narrow range for size and volume. Based on the analytical results for one example of each of the two formation processes, Builth reported that cultural-versus-natural origin could be easily determined. If the average diagonal measurement across the base of a set of stones is less than 200–350 millimetres, the formation is cultural. Anything outside of this range results from a natural event— which could only be a tree heave.

These results need to be interpreted against their methodological limitations, which are that sample size is limited to one in each case; geological processes were erroneously eliminated as a causative factor; and no allowance was made for change over time. There is also a degree of uncertainty around how stones were selected for analysis. It seems that not every stone was collected from within arbitrarily defined collecting areas. This point is important given that many stone circles were found very close to one another.55

There is also the emphasis on absence of wood as evidence for a cultural circle:

In the study areas, wherever trees had grown through the basalt and died, there was evidence of this effect in the form of dead wood and roots, remaining even though the tree had been long dead. However, these are areas where bushfires have not occurred for possibly hundreds of years.56

Here Builth is stating that a fallen tree will be recognisable by the dead wood and roots for a very long time as no bushfires have been present for hundreds of years to destroy the evidence. This in itself would suggest that there is no reason even to measure, because if there is no wood or root debris then formation can only be due to human action, as she reasoned earlier. However, in regard to bushfires, Massola refers to particularly severe fires in 1874 and 1901 in the region.57 This is supported by newspaper reports from the 1800s. For example:

… the southern portion of this locality has also suffered through the fire which started in the vicinity of Lake Condah Mission Station on Saturday last [but] does not seem to have claimed much attention, simply, I suppose because it is looked upon as a necessary evil to have a fire on this part of the country known as the ‘Stones’ every year to eradicate the wild dogs and other vermin … Saturday as will be remembered was both hot and windy and the fire gained ground rapidly. On Sunday and Monday, it was still burning, although all the male inhabitants of the Mission Station and the people who had somewhat checked further progress in the southern direction, which caused it, aided by the wind, to travel towards Lake Condah and Mount Eccles …58

Clearly, the absence of associated wood and roots inside a stone circle is not evidence alone for classifying a circle as cultural. The metrical results presented by Builth are measures of partial, single events resulting from an uncertain cause. This outcome could potentially have been offset by introducing a control group and perhaps more importantly by increasing the sample size. Geological processes and bushfire impact also need to be acknowledged.

The construction of archaeological classifications has long been recognised as a high-risk area for introducing bias.59 Clarke highlighted this very problem at Lake Condah:

Implicit in the recording of these sites are our own culturally based interpretations of how we think these sites would have operated as traps, channels and so on. This is one of the problems with the terminology adopted by Coutts et al. (1978). They have used terms that carry with them a whole spectrum of meanings that extend beyond the structural and morphological traits of the sites, and imply by such association a range of attributes and functions that have not been demonstrated or argued from the archaeological evidence.60

As discussed in the previous section, Builth’s classification of a cultural circle was based on two fundamental errors: that both geological processes and bushfires are irrelevant to classifying stone circles. This bias was inevitably transported into the next step: spatial mapping.

Builth followed up her metrical analysis with a geographical information system (GIS) approach, which she used to generate an impressive simulation of an operating fish-trap complex on the lava plain. The data were also run through various software in order to specify spatial relationships between heritage features—that is, fish traps and stone circles—and revealed a close spatial relationship between these features, thus confirming the findings of Coutts, Frank and Hughes forty years earlier. Was this meaningful? Yes, if the stone circles were reliably classified, but, as presented here, they were not. As with the Moyjil midden, discussed in Chapter 12, we have a named feature but no evidence for a robust cultural feature.

As it was in the mid-1990s, we are still no closer to distinguishing a naturally formed circle of basalt rocks from a culturally formed one. For this reason alone, it is not possible to reliably estimate human populations from the numbers of stone circles. It is then worthwhile to consider the remainder of Builth’s innovative research into evidence for complexity in food supply, storage and distribution, in view of its contribution to Pascoe’s theories of sedentism and aquaculture.

Builth inspected the mature trees in her survey area and noticed that some had been hollowed out by burning. She wondered if the burning had been caused by deliberately heating the interior to smoke eels as a means of preserving them.61 She also noticed holes in the upper branches of some trees and suggested that these were chimneys for the internal fire.

The idea of smoking eels as a preservative was a novel hypothesis but lacked ethnographic or ethnohistorical support, as Builth noted: ‘to my knowledge, no local oral histories exist of manna gums being modified and used for eel smoking (personal communication, Gunditjmara Elders Keith Saunders and Johnny Lovett, 2001)’.62

James Dawson recorded numerous and detailed observations of various Indigenous activities at Lake Condah in the mid to late 1800s. He relates the spearing of eels by day and night, baiting freshwater fish, using baskets as a drag-net, damming rivulets with small stones, driving fish downstream into baskets, building stone barriers across rapid streams, diverting currents by use of a funnel-mouthed basket placed in a small opening, and building clay embankments across streams when the marshes were flooded. In fact, he described every activity for which archaeological evidence exists. He did not describe smoking eels inside mature trees but he did remark that ‘fish … are quickly cooked by spreading them on hot embers raked out of the fire and are lifted with slips of bark and eaten hot’.63 There are a few accounts from elsewhere in Australia of fish being dried and thus preserved for a few days or possibly a few months, and, for some, to add flavour.64

At Lake Condah, Dawson also mentions that:

Each tribe has allotted to it a portion of a stream, now known as Salt Creek; and the usual stone barrier is built by each family, with the eel basket in the opening. Large numbers are caught during the fishing season. For a month or two the banks of the Salt Creek presented the appearance of a village … No other tribe can catch them without permission, which is generally granted, except to unfriendly tribes from a distance, whose attempts to take eels by force have often led to quarrels and bloodshed.65

This portrays a regulated system of permission and entitlement practised among tribes during seasonal abundance. However, Builth considered the ethnographic and ethnohistoric observations to be unreliable66 and pushed ahead with finding evidence for ‘smoking trees’. She noticed that ‘Most of the trees had been burnt inside and yet showed no evidence of external burning—thus dismissing the cause of burning as bush fire related’67 and believed this to be key evidence for fires being deliberately contained inside the trees and managed in order to smoke eels.

During recent bushfires in southern Australia this very phenomenon was recorded, as shown in the photo in page 4 of the photo section. Here, the tree is well alight internally but shows no burning externally. Given the number and intensity of fires recorded since European settlement in western Victoria, as mentioned earlier, ‘chimney trees’ or ‘smoking trees’ require additional evidence.

Mature large trees with hollowed-out interiors (see overleaf) were more plentiful in the 1800s before large-scale land clearance, which was relatively common across south-eastern Australia.68 River red gums with large openings at the base were known to be used as ‘shelter’ trees by Aboriginal people.69 Small cooking or warming fires were often lit at the entrance of the tree, or, if the internal space was large enough, a small fire was maintained inside; these fires caused internal blackening from smoke, extending up into the trunk. Fires were also lit inside trees to smoke out possums.70

Builth did not accept that any of these activities were relevant at Lake Condah, and pursued the notion that eels could be cured inside trees. She reasoned that oil might be present in the soil due to ‘domestic family baking on the stones’71—‘stones’ in this case being heated stones placed in the tree or heated inside the tree,72 and ‘family baking’ being, presumably, eels. However, unhelpfully, no stone of any description or other archaeological material—such as stone tools, shell or animal bone—was found inside any of the fifty-two mature trees inspected by Builth.

Mature ‘shelter type’ tree, Canberra.

In the absence of any actual archaeological evidence, traces of eel oil remained the only way of providing support for the ‘smoking trees’ theory. Four trees were selected for sampling sediment from the internal floor. The samples were sent for biochemical analysis (gas chromatography) and found to be generally degraded, but two were deemed sufficiently viable. The degraded but apparently viable samples revealed the presence of unsaturated long-chain fatty acids (those classified as 16:1, 18:1, 18:2, 20:4 and 20:5). Builth focused on fatty acids 20:4 and 20:5, which she said are:

commonly found in aquatic animals in relatively high levels and are rare in plants. Given the large amounts of long chain fatty acids, an aquatic source is most likely … Given the context of the samples the most likely source of the residues is eel processing.73

Fatty acid 20:4 is arachidonic acid, a polyunsaturated fatty acid actually found in a range of mammals, including humans, as well as in fish; while 20:5 is timnodonic acid, a polyunsaturated fatty acid found in fish as well as other animals.74 Biochemically, the presence of a range of long-chain degraded fatty acids appeared to support Builth’s theory that the lipids were more likely to be of fish origin than mammal. However, at Lake Condah eight fish species have been identified75 and timnodonic acid is not a unique signature for eels.

Builth then compared the biochemical results with those from a sample of recently cooked eel flesh and a sample of recently smoked and cooked eel flesh. She found a good fit for the chromatograms for both sets of samples (tree-extracted and recently cooked/smoked), but, as with all scientific testing, it is necessary to scrutinise the sampling methodology. The age of the tree samples is unknown, leaving it impossible to estimate oxidation and microbial activity in altering the composition and integrity of soil lipids over time. Further, as with the stone circles, this analysis involved just two archaeological samples and two recent samples. No controls were introduced as a measure of confidence, and no blanks were used to check for contamination. No samples were taken from elsewhere inside the tree—for example, higher up on the inside of the trunk, where volatile acids may have been trapped—or, as remarked by Ian Keen, from soil outside of the trees,76 as a marker of comparison. Sampling from trees of different ages would also have made sense in terms of identifying standards and baselines, in that soil communities vary significantly with the level of maturity of a tree.

Establishing baselines and standards by introducing a control group, blanks and test runs larger than one or two samples is a basic scientific principle. Further, reliance on multiple lines of inquiry is far preferable. Builth’s two sediment samples were the only line of evidence presented to argue for a tradition of smoking eels inside mature trees for possibly thousands of years.

As before, rather than focus on quality control and lack of supporting evidence, an obvious and yet highly important question was not posed during the research into smoking of eels inside mature trees: by what other means might phospholipids (fish oil) get into sediments inside a tree cavity?

Lake Condah, Condah Swamp and the surrounding savannah woodland, prior to the introduction of European water and land management, was a ‘pretty gem of a place’77 and a haven for a wide range of fish, birds, mammals, reptiles and insects. Even after drainage works, a surprisingly high number of birds were reported for the Western District in the mid-1970s.78 Of these, a number of the listed birds are known to consume fish and to perch in nearby trees to eat their catch, the darter bird being an obvious example.

Tiger quolls and eastern quolls, although now locally extinct or rare, were once prevalent in western Victoria.79 They are carnivorous hunters but will also scavenge fish remains, for example, from fishing expeditions.80 They also prefer cavities in mature trees for sleeping and making latrine areas. Another competent scavenger is the brush-tailed possum, which behaves similarly by sleeping and defecating in tree cavities. Dingoes are also prime scavengers and defecate and urinate in or around trees.81 The very mature tree from which a sample was taken was photographed without a scale but was obviously quite a large cavity, easily accessible by larger mammals.82

Apart from faeces and urine being deposited inside tree cavities, natural mortality takes place. And, as mentioned earlier, Indigenous people are also well known to have made a small fire while sheltering inside mature trees. At Lake Condah it is reasonable to consider that eels would be consumed at these times.

Given the wide range of possible agents and activities leading to traces of fish oil in sediments inside mature trees, it would have been valuable for Builth to sample sediments from trees known to be used by mammals and roosting birds, and also trees where an animal had died. The absence of testing across a range of environmental conditions and scenarios undermines confidence in the tested samples as being biomarkers unique to eels.

Left with, at best, tenuous evidence for smoking eels inside trees, the only unexplored avenue to possibly provide evidence is feasibility.

The hypothetical method of domestic baking on rocks to smoke eels inside a confined tree hollow was not described in detail by Builth. Nor were details of this activity given by Gunditjmara elder Eileen Alberts, when fifteen years later recalling that her family had used trees for this purpose.83 Instead, Builth focused more broadly on the very real difficulty of digging pit ovens into the soil-deficient basalt lava plain— which, she suggested, was overcome by burying heated rocks inside hollowed-out trees.84 This would of course generate heat rather than smoke, but could perhaps dry the fish. The absence of heat-retaining rocks inside the inspected mature trees has been noted previously.

Most backyard eel curing today makes use of a barrel-shaped oven (similar to a hollow tree trunk), either electric or wood-heated. The eels are hung inside and exposed to a temperature of 60°C for some three hours and then 80°C for a further four hours.85 The trees recorded by Builth do not have evidence for an internal rack on which eels could be laid or from which they could be hung. Perhaps the eels were impaled on wooden sticks and stood upright inside the tree and exposed to smoke or heat. Maintaining 60°C for three hours and then 80°C for four hours would necessitate heated rocks or fire to be introduced periodically into the tree. The average internal diameter of the trees was measured at 1–1.5 metres, which is about the same length as an average adult eel. Juggling eels and heated rocks inside a confined space seems a complicated manoeuvre to undertake for possibly hundreds or even thousands of eels during peak season. It would seem far easier, in all ways, to cook the eels in the open, as detailed elsewhere for smoking fish.86

The logistics of abundant eels being dried or smoked inside confined spaces would have required hundreds of trees operating simultaneously and continuously over a season. It would have presented quite a sight on the lava-flow plain, and yet not a single person remarked on it— although Builth refers to an illustration by William Blandowski, which she describes as Aboriginal people with ‘food prepared for cooking or smoking in a tree—feasibly eels’.87 This illustration is, however, a cropped image of Aboriginal people ‘smoking possums out of trees and preparing possum skins for cloaks’.88

There is no reliable or convincing archaeological or ethnographic evidence for thousands of eels being smoke-dried and stored in the Lake Condah district before or at colonisation. The temporary caching of live eels may well have taken place, however, in view of another account by Dawson:

The small fish ‘tarropatt’ and others of a similar description, are caught in a rivulet which runs into Lake Colungulac, near Camperdown, by damming it up with stones, and placing a basket in a gap of the dam. The women and children go up the stream and drive the fish down; and when the basket is full, it is emptied into holes dug in the ground to prevent them from escaping.89

Logically these holes would be close to the trap system, and some might be given a low stone rim to heighten water levels. Perhaps some of the stone circles were used to cache live fish for a day or two.

Archaeological investigations over many decades in western Victoria have confirmed the existence of a complex and long-established fish-trap system, as described and depicted by early explorers, settlers and others. Archaeology has not provided convincing evidence for the preservation and storage of fish in order to generate a trade item.

Stone circles have been well recorded around Lake Condah but remain in an unknown ratio of cultural to natural formations. In view of the nineteenth-century ethnographies and illustrations and the excavation of two circles,90 there is no doubt that some circles represent the base for constructing a dwelling. Other circles close to the fish-trap complex may have been used for caching live eels or to serve some other purpose related to the ponding and channelling of fish within the system. Still others may be due to a range of natural phenomena, such as geological processes and tree falls.

Pascoe’s estimate of 10,000 people in the Western District prior to European settlement is without archaeological support. It also defies census records. Census estimates for 1836 indicate about 5000 Aboriginal people for the whole of Victoria,91 and the entire population of Australia prior to 1788 is estimated at less than one million.92

Pascoe is some fifty years behind the scholarly discussions that have traversed Australia, Papua New Guinea, Polynesia and more widely across the Pacific ethnographically. Archaeologists and anthropologists have not conspired to ‘hide’ evidence of agriculture or aquaculture but, instead, have systematically and objectively recorded Aboriginal subsistence practices. As demonstrated in earlier chapters, fieldwork has led to a wealth of detail describing complex ecological sustainability achieved via personal and social agency within a natural and spiritual world order. It is Pascoe who adds pejoratives such as ‘primitive’, ‘simple’ and ‘mere’ (pages 2, 86, 183) to the term hunter-gatherer, and it is he who argues for a very different scenario—that of agriculture and aquaculture.

The fish-trap complex of Budj Bim has been the focus of attention from admiring Europeans since the mid-1800s and of archaeologists since the 1970s; all of the latter have referred to the ethnographic records. Much of the earlier work was undertaken with Indigenous collaboration, resulting in recorded sites, management plans and ongoing research.

This collaborative and investigatory trend has continued into the twenty-first century with the huge efforts undertaken by archaeologists such as Builth and McNiven. Each has consulted and engaged with communities across all aspects of their work.

All archaeological investigations are vulnerable when applying so many different methods and complicated analytical tools. But this is what also achieves remarkable results. In the end, the total archaeological effort in the Western District has been sophisticated and comprehensive. If some methods have been less reliable than others, it has been due to the difficult, complex and diverse environmental conditions of the region rather than individual failings.

Recommendations arising from the comprehensive heritage management plan instigated by VAS in the early 1990s93 resulted in national-significance listing of the complex. Successful World Heritage nomination of the Budj Bim cultural site in 201994 is an extraordinary achievement, built from years of dedication by many Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. As with all investigations, mistakes, setbacks, disagreements and misfortunes underlie the good outcomes. At Lake Condah, there is no disputing the high significance and heritage value of Budj Bim.