Chapter 4

My Interrupted Flight Toward the Himalayas

“Leave your classroom on some trifling pretext, and engage a hackney carriage. Stop in the lane where no one in my house can see you.”

These were my final instructions to Amar Mitter, a high school friend who planned to accompany me to the Himalayas. We had chosen the following day for our flight. Precautions were necessary, as my brother Ananta exercised a vigilant eye. He was determined to foil the plans of escape that he suspected were uppermost in my mind. The amulet, like a spiritual yeast, was silently at work within me. I hoped to find, amid the Himalayan snows, the master whose face often appeared to me in visions.

The family was living now in Calcutta, where Father had been permanently transferred. Following the patriarchal Indian custom, Ananta had brought his bride to live in our home. There in a small attic room I engaged in daily meditations and prepared my mind for the divine search.

The memorable morning arrived with inauspicious rain. Hearing the wheels of Amar’s carriage in the road, I hastily tied together a blanket, a pair of sandals, two loincloths, a string of prayer beads, Lahiri Mahasaya’s picture, and a copy of the Bhagavad Gita. This bundle I threw from my third-story window. I ran down the steps and passed my uncle, buying fish at the door.

“What is the excitement?” His gaze roved suspiciously over my person.

I gave him a noncommittal smile and walked to the lane. Retrieving my bundle, I joined Amar with conspiratorial caution. We drove to Chandni Chauk, a merchandise centre. For months we had been saving our tiffin money to buy English clothes. Knowing that my clever brother could easily play the part of a detective, we thought to outwit him by wearing European garb.

On the way to the station, we stopped for my cousin, Jotin Ghosh, whom I called Jatinda. He was a new convert, longing for a guru in the Himalayas. He donned the new suit we had in readiness. Well camouflaged, we hoped! A deep elation possessed our hearts.

“All we need now are canvas shoes.” I led my companions to a shop displaying rubber-soled footwear. “Articles of leather, got only through the slaughter of animals, should be absent on this holy trip.” I halted on the street to remove the leather cover from my Bhagavad Gita, and the leather straps from my English-made sola topee (helmet).

At the station we bought tickets to Burdwan, where we planned to transfer for Hardwar in the Himalayan foothills. As soon as the train, like ourselves, was in flight, I gave utterance to a few of my glorious anticipations.

“Just imagine!” I ejaculated. “We shall be initiated by the masters and experience the trance of cosmic consciousness. Our flesh will be charged with such magnetism that wild animals of the Himalayas will come tamely near us. Tigers will be no more than meek house cats awaiting our caresses!”

This remark—picturing a prospect I considered entrancing, both metaphorically and literally—brought an enthusiastic smile from Amar. But Jatinda averted his gaze, directing it through the window at the scampering landscape.

“Let the money be divided in three portions.” Jatinda broke a long silence with this suggestion. “Each of us should buy his own ticket at Burdwan. Thus no one at the station will surmise that we are running away together.”

I unsuspectingly agreed. At dusk our train stopped at Burdwan. Jatinda entered the ticket office; Amar and I sat on the platform. We waited fifteen minutes, then made unavailing inquiries. Searching in all directions, we shouted Jatinda’s name with the urgency of fright. But he had faded into the dark unknown surrounding the little station.

I was completely unnerved, shocked to a peculiar numbness. That God would countenance this depressing episode! The romantic occasion of my first carefully planned flight after Him was cruelly marred.

“Amar, we must return home.” I was weeping like a child. “Jatinda’s callous departure is an ill omen. This trip is doomed to failure.”

“Is this your love for the Lord? Can’t you stand the little test of a treacherous companion?”

Through Amar’s suggestion of a divine test, my heart steadied itself. We refreshed ourselves with famous Burdwan sweetmeats, sitabhog (food for the goddess) and motichur (nuggets of sweet pearl). In a few hours we entrained for Hardwar, via Bareilly. Changing trains the following day at Moghul Serai, we discussed a vital matter as we waited on the platform.

“Amar, we may soon be closely questioned by railway officials. I am not underrating my brother’s ingenuity! No matter what the outcome, I will not speak untruth.”

“All I ask of you, Mukunda, is to keep still. Don’t laugh or grin while I am talking.”

At this moment a European station-agent accosted me. He waved a telegram whose import I immediately grasped.

“Are you running away from home in anger?”

“No!” I was glad his choice of words permitted me to make emphatic reply. Not anger but “divinest melancholy” was responsible, I knew, for my unconventional behaviour.

The official then turned to Amar. The duel of wits that followed hardly permitted me to maintain the counselled stoic gravity.

“Where is the third boy?” The man injected a full ring of authority into his voice. “Come now—speak the truth!”

“Sir, I notice you are wearing eyeglasses. Can’t you see that we are only two?” Amar smiled impudently. “I am not a magician; I can’t conjure up a third boy.”

The official, noticeably disconcerted by this impertinence, sought a new field of attack. “What is your name?”

“I am called Thomas. I am the son of an English mother and a converted Christian Indian father.”

“What is your friend’s name?”

“I call him Thompson.”

By this time my inward mirth had reached a zenith; I unceremoniously made for the train, which was providentially whistling for departure. Amar followed with the official, who was credulous and obliging enough to put us into a European compartment. It evidently pained him to think of two half-English boys travelling in the section allotted to natives. After his polite exit, I lay back on the seat and laughed uproariously. Amar wore an expression of blithe satisfaction at having outwitted a veteran European official.

On the platform I had contrived to read the telegram. From my brother Ananta, it went thus: “Three Bengali boys in English clothes running away from home toward Hardwar via Moghul Serai. Please detain them until my arrival. Ample reward for your services.”

“Amar, I told you not to leave marked timetables in your home.” My glance was reproachful. “Brother must have found one there.”

My friend sheepishly acknowledged the thrust. We halted briefly in Bareilly, where Dwarka Prasad 1 awaited us with a telegram from Ananta. Dwarka tried valiantly to detain us; I convinced him that our flight had not been undertaken lightly. As on a previous occasion, Dwarka refused my invitation to set out for the Himalayas.

While our train stood in a station that night, and I was half asleep, Amar was awakened by another questioning official. He, too, fell a victim to the hybrid charms of “Thomas” and “Thompson.” The train bore us triumphantly into a dawn arrival at Hardwar. The majestic mountains loomed invitingly in the distance. We dashed through the station and entered the freedom of city crowds. Our first act was to change into native costume, as Ananta had somehow penetrated our European disguise. A premonition of capture weighed on my mind.

Deeming it advisable to leave Hardwar at once, we bought tickets to proceed north to Rishikesh, a soil long hallowed by the feet of many masters. I had already boarded the train, while Amar lagged on the platform. He was brought to an abrupt halt by a shout from a policeman. An unwelcome guardian, the officer escorted Amar and me to a police-station bungalow and took charge of our money. He explained courteously that it was his duty to hold us until my elder brother arrived.

Learning that the truants’ destination had been the Himalayas, the officer related a strange story.

“I see you are crazy about saints! You will never meet a greater man of God than the one I saw only yesterday. My brother officer and I first encountered him five days ago. We were patrolling by the Ganges, on a sharp lookout for a certain murderer. Our instructions were to capture him, alive or dead. He was known to be masquerading as a sadhu in order to rob pilgrims. A short way before us, we spied a figure which resembled the description of the criminal. He ignored our command to stop; we ran to overpower him. Approaching his back, I wielded my axe with tremendous force; the man’s right arm was severed almost completely from his body.

“Without outcry or any glance at the ghastly wound, the stranger astonishingly continued his swift pace. As we jumped in front of him, he spoke quietly.

“‘I am not the murderer you are seeking.’

“I was deeply mortified to see I had injured the person of a divine-looking sage. Prostrating myself at his feet, I implored his pardon, and offered my turban cloth to staunch the heavy spurts of blood.

“‘Son, that was just an understandable mistake on your part.’ The saint regarded me kindly. ‘Run along, and don’t reproach yourself. The Beloved Mother is taking care of me.’ He pushed his dangling arm into its stump and lo! it adhered; the blood inexplicably ceased to flow.

“‘Come to me under yonder tree in three days and you will find me fully healed. Thus you will feel no remorse.’

“Yesterday my brother officer and I went eagerly to the designated spot. The sadhu was there and allowed us to examine his arm. It bore no scar nor trace of hurt!

“‘I am going via Rishikesh to the Himalayan solitudes.’ The sadhu blessed us as he departed quickly. I feel that my life has been uplifted through his sanctity.”

The officer concluded with a pious ejaculation; his experience had obviously moved him beyond his usual depths. With an impressive gesture, he handed me a printed clipping about the miracle. In the usual garbled manner of the sensational type of newspaper (not missing, alas! even in India), the reporter’s version was slightly exaggerated: it indicated that the sadhu had been almost decapitated!

Amar and I lamented that we had missed the great yogi who could forgive his persecutor in such a Christlike way. India, materially poor for the last two centuries, yet has an inexhaustible fund of divine wealth; spiritual “skyscrapers” may occasionally be encountered by the wayside, even by worldly men like this policeman.

We thanked the officer for relieving our tedium with his marvellous story. He was probably intimating that he was more fortunate than we: he had met an illumined saint without effort; our earnest search had ended, not at the feet of a master, but in a coarse police station!

So near the Himalayas and yet, in our captivity, so far, I told Amar I felt doubly impelled to seek freedom.

“Let us slip away when opportunity offers. We can go on foot to holy Rishikesh.” I smiled encouragingly.

But my companion had turned pessimist as soon as the stalwart prop of our money had been taken from us.

“If we started a trek over such dangerous jungle land, we should finish, not in the city of saints, but in the stomachs of tigers!”

Ananta and Amar’s brother arrived after three days. Amar greeted his relative with affectionate relief. I was unreconciled; Ananta got no more from me than a severe upbraiding.

“I understand how you feel.” My brother spoke soothingly. “All I ask of you is to accompany me to Banaras to meet a certain sage, and go on to Calcutta to visit our grieving father for a few days. Then you may resume your search here for a master.”

Amar entered the conversation at this point to disclaim any intention of returning to Hardwar with me. He was enjoying the familial warmth. But I knew I would never abandon the quest for my guru.

Our party entrained for Banaras. There I had a singular and instant response to a prayer.

A clever scheme had been prearranged by Ananta. Before seeing me in Hardwar he had stopped in Banaras to ask a scriptural authority to interview me later. The pundit, and his son also, had promised Ananta that they would attempt to dissuade me from becoming a sannyasi. 2

Ananta took me to their home. The son, a young man of ebullient manner, greeted me in the courtyard. He engaged me in a lengthy philosophic discourse. Professing to have a clairvoyant knowledge of my future, he discountenanced my idea of being a monk.

“You will meet continual misfortune, and be unable to find God, if you insist on deserting your ordinary responsibilities! You cannot work out your past karma 3 without worldly experiences.”

Immortal words from the Bhagavad Gita 4 rose to my lips in reply: “ ‘Even he with the worst of karma who ceaselessly meditates on Me quickly loses the effects of his past bad actions. Becoming a high-souled being, he soon attains perennial peace. Know this for certain: the devotee who puts his trust in Me never perishes!’ ”

But the forceful prognostications of the young man had slightly shaken my confidence. With all the fervour of my heart I prayed silently to God:

“Please solve my bewilderment and answer me, right here and now, if Thou dost desire me to lead the life of a renunciant or a worldly man!”

I noticed a sadhu of noble countenance standing just outside the compound of the pundit’s house. Evidently he had overheard the spirited conversation between the self-styled clairvoyant and me, for the stranger called me to his side. I felt a tremendous power flowing from his calm eyes.

“Son, don’t listen to that ignoramus. In response to your prayer, the Lord tells me to assure you that your sole path in this life is that of the renunciant.”

With astonishment as well as gratitude, I smiled happily at this decisive message.

“Come away from that man!” The “ignoramus” was calling me from the courtyard. My saintly guide raised his hand in blessing and slowly departed.

“That sadhu is just as crazy as you are.” It was the hoary-headed pundit who made this charming observation. He and his son were gazing at me lugubriously. “I have heard that he, too, has left his home in a vague search for God.”

I turned away. To Ananta I remarked that I would not engage in further discussion with our hosts. My discouraged brother agreed to an immediate departure; we soon entrained for Calcutta.

“Mr. Detective, how did you discover I had fled with two companions?” I vented my lively curiosity to Ananta during our homeward journey. He smiled mischievously.

“At your school, I found that Amar had left his classroom and had not returned. I went to his home the next morning and unearthed a marked timetable. Amar’s father was just leaving by carriage and was talking to the coachman.

“‘My son will not ride with me to his school this morning. He has disappeared!’ the father moaned.

“‘I heard from a brother coachman that your son and two others, dressed in European suits, boarded the train at Howrah Station,’ the man stated. ‘They made a present of their leather shoes to the cab driver.’

“Thus I had three clues—the timetable, the trio of boys, and the English clothing.”

I was listening to Ananta’s disclosures with mingled mirth and vexation. Our generosity to the coachman had been slightly misplaced!

“Of course I rushed to send telegrams to station officials in all the cities that Amar had underlined in the timetable. He had checked Bareilly, so I wired your friend Dwarka there. After inquiries in our Calcutta neighborhood, I learned that cousin Jatinda had been absent one night but had arrived home the following morning in European garb. I sought him out and invited him to dinner. He accepted, quite disarmed by my friendly manner. On the way I led him unsuspectingly to a police station. He was surrounded by several officers whom I had previously selected for their ferocious appearance. Under their formidable gaze, Jatinda agreed to account for his mysterious conduct.

“‘I started for the Himalayas in a buoyant spiritual mood,’ he explained. ‘Inspiration filled me at the prospect of meeting the masters. But as soon as Mukunda said, “During our ecstasies in the Himalayan caves, tigers will be spellbound and sit around us like tame pussies,” my spirits froze; beads of perspiration formed on my brow. “What then?” I thought. “If the vicious nature of the tigers be not changed through the power of our spiritual trance, shall they treat us with the kindness of house cats?” In my mind’s eye, I already saw myself the compulsory inmate of some tiger’s stomach—entering there not at once with the whole body, but by instalments of its several parts!’ ”

My anger at Jatinda’s vanishment evaporated in laughter. The hilarious explanation on the train was worth all the anguish he had caused me. I must confess to a slight feeling of satisfaction: Jatinda, too, had not escaped an encounter with the police!

“Ananta, 5 you are a born sleuthhound!” My glance of amusement was not without some exasperation. “And I shall tell Jatinda I am glad he was prompted by no mood of treachery, as it appeared, but only by the prudent instinct of self-preservation!”

At home in Calcutta, Father touchingly requested me to curb my roving feet until, at least, the completion of my high school studies. In my absence, he had lovingly hatched a plot by arranging for a saintly pundit, Swami Kebalananda, to come regularly to the house.

“The sage will be your Sanskrit tutor,” my parent announced confidently.

Father hoped to satisfy my religious yearnings by instruction from a learned philosopher. But the tables were subtly turned: my new teacher, far from offering intellectual aridities, fanned the embers of my God-aspiration. Unknown to Father, Swami Kebalananda was an exalted disciple of Lahiri Mahasaya. The peerless guru had possessed thousands of disciples, silently drawn to him by the irresistibility of his divine magnetism. I learned later that Lahiri Mahasaya had often characterised Kebalananda as rishi or illumined sage. 6

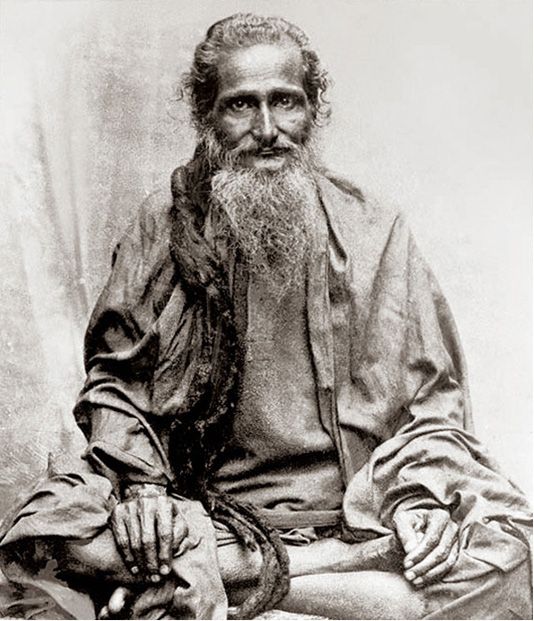

Luxuriant curls framed my tutor’s handsome face. His dark eyes were guileless, with the transparency of a child’s. All the movements of his slight body were marked by a restful deliberation. Ever gentle and loving, he was firmly established in the infinite consciousness. Many of our happy hours together were spent in deep Kriya meditation.

SWAMI KEBALANANDA

Yoganandaji’s beloved Sanskrit tutor

Kebalananda was a noted authority on the ancient shastras or sacred books; his erudition had earned him the title of “Shastri Mahasaya,” by which he was usually addressed. But my progress in Sanskrit scholarship was unnoteworthy. I sought every opportunity to forsake prosaic grammar and to talk of yoga and Lahiri Mahasaya. My tutor obliged me one day by telling me something of his own life with the master.

“Rarely fortunate, I was able to remain near Lahiri Mahasaya for ten years. His Banaras home was my nightly goal of pilgrimage. The guru was always present in a small front parlour on the first floor. As he sat in lotus posture on a backless wooden seat, his disciples garlanded him in a semicircle. His eyes sparkled and danced with the joy of the Divine. They were ever half closed, peering through the inner telescopic orb into a sphere of eternal bliss. He seldom spoke at length. Occasionally his gaze would focus on a student in need of help; healing words poured then like an avalanche of light.

“An indescribable peace blossomed within me at the master’s glance. I was permeated with his fragrance, as though from a lotus of infinity. To be with him, even without exchanging a word for days, was experience which changed my entire being. If any invisible barrier rose in the path of my concentration, I would meditate at the guru’s feet. There the most tenuous states came easily within my grasp. Such perceptions eluded me in the presence of lesser teachers. The master was a living temple of God, whose secret doors were open to all disciples through devotion.

“Lahiri Mahasaya was no bookish interpreter of the scriptures. Effortlessly he dipped into the ‘divine library.’ Foam of words and spray of thoughts gushed from the fountain of his omniscience. He had the wondrous clavis that unlocked the profound philosophical science hidden ages ago in the Vedas. 7 If asked to explain the different planes of consciousness mentioned in the ancient texts, he would smilingly assent.

“‘I will undergo those states, and presently tell you what I perceive.’ He was thus diametrically unlike the teachers who commit scripture to memory and then give forth unrealized abstractions.

“‘Please expound the holy stanzas as the meaning occurs to you.’ The taciturn guru often gave this instruction to a nearby disciple. ‘I will guide your thoughts, that the right interpretation be uttered.’ In this way many of Lahiri Mahasaya’s perceptions came to be recorded, with voluminous commentaries by various students.

“The master never counselled slavish belief. ‘Words are only shells,’ he said. ‘Win conviction of God’s presence through your own joyous contact in meditation.’

“No matter what the disciple’s problem, the guru advised Kriya Yoga for its solution.

“‘The yogic key will not lose its efficiency when I am no longer present in the body to guide you. This technique cannot be bound, filed, and forgotten, in the manner of theoretical inspirations. Continue ceaselessly on your path to liberation through Kriya, whose power lies in practice.’

“I myself consider Kriya the most effective device of salvation through self-effort ever to be evolved in man’s search for the Infinite.” Kebalananda concluded with this earnest testimony. “Through its use, the omnipotent God, hidden in all men, became visibly incarnated in the flesh of Lahiri Mahasaya and of a number of his disciples.”

A Christlike miracle by Lahiri Mahasaya took place in Kebalananda’s presence. My saintly tutor recounted the story one day, his eyes remote from the Sanskrit texts on the table before us.

“A blind disciple, Ramu, aroused my active pity. Should he have no light in his eyes, when he faithfully served our master, in whom the Divine was fully blazing? One morning I sought to speak to Ramu, but he sat for patient hours fanning the guru with a handmade palm-leaf punkha . When the devotee finally left the room, I followed him.

“‘Ramu, how long have you been blind?’

“‘From my birth, sir! Never have my eyes been blessed with a glimpse of the sun.’

“‘Our omnipotent guru can help you. Please make a supplication.’

“The following day Ramu diffidently approached Lahiri Mahasaya. The disciple felt almost ashamed to ask that physical wealth be added to his spiritual superabundance.

“‘Master, the Illuminator of the cosmos is in you. I pray you to bring His light into my eyes, that I perceive the sun’s lesser glow.’

“‘Ramu, someone has connived to put me in a difficult position. I have no healing power.’

“‘Sir, the Infinite One within you can certainly heal.’

“‘That is indeed different, Ramu. God’s limit is nowhere! He who ignites the stars and the cells of flesh with mysterious life-effulgence can surely bring the lustre of vision into your eyes.’ The master touched Ramu’s forehead at the point between the eyebrows. 8

“‘Keep your mind concentrated there, and frequently chant the name of the prophet Rama for seven days. The splendour of the sun shall have a special dawn for you.’

“Lo! in one week it was so. For the first time, Ramu beheld the fair face of nature. The Omniscient One had unerringly directed his disciple to repeat the name of Rama, adored by him above all other saints. Ramu’s faith was the devotionally ploughed soil in which the guru’s powerful seed of permanent healing sprouted.” Kebalananda was silent for a moment, then paid a further tribute to his guru.

“It was evident in all miracles performed by Lahiri Mahasaya that he never allowed the ego-principle 9 to consider itself a causative force. By the perfection of his surrender to the Prime Healing Power, the master enabled It to flow freely through him.

“The numerous bodies that were spectacularly healed through Lahiri Mahasaya eventually had to feed the flames of cremation. But the silent spiritual awakenings he effected, the Christlike disciples he fashioned, are his imperishable miracles.”

I never became a Sanskrit scholar; Kebalananda taught me a diviner syntax.

2 Literally, “renunciant”; from Sanskrit verb roots, “to cast aside.”

3 Effects of past actions, in this or a former life; from the Sanskrit verb kri, “to do.”

4 Chapter IX, verses 30–31.

5 I always addressed him as Ananta-da. Da is a respectful suffix that brothers and sisters add to the name of their eldest brother.

6 At the time of our meeting, Kebalananda had not yet joined the Swami Order and was generally called “Shastri Mahasaya.” To avoid confusion with the name of Lahiri Mahasaya and of Master Mahasaya (chapter 9), I am referring to my Sanskrit tutor only by his later monastic name of Swami Kebalananda. His biography has been recently published in Bengali. Born in the Khulna district of Bengal in 1863, Kebalananda gave up his body in Banaras at the age of sixty-eight. His family name was Ashutosh Chatterji.

7 Over 100 canonical books of the ancient four Vedas are extant. In his Journal Emerson paid this tribute to Vedic thought: “It is sublime as heat and night and a breathless ocean. It contains every religious sentiment, all the grand ethics which visit in turn each noble poetic mind ....It is of no use to put away the book; if I trust myself in the woods or in a boat upon the pond, Nature makes a Brahmin of me presently: eternal necessity, eternal compensation, unfathomable power, unbroken silence ....This is her creed. Peace, she saith to me, and purity and absolute abandonment these panaceas expiate all sin and bring you to the beatitude of the Eight Gods.”

8 The seat of the “single” or spiritual eye. At death the consciousness of man is usually drawn to this holy spot, accounting for the upraised eyes found in the dead.

9 The ego-principle, ahamkara (lit., “I do”) is the root cause of dualism or the seeming separation between man and his Creator. Ahamkara brings human beings under the sway of maya (cosmic delusion), by which the subject (ego) falsely appears as object; the creatures imagine themselves to be creators.

“Naught of myself I do!”

Thus will he think, who holds the truth of truths....

Always assured: “This is the sense-world plays

With senses.” (V:8–9)

Seeing, he sees, indeed, who sees that works

Are Nature’s wont, for Soul to practice by;

Acting, yet not the agent. (XIII:29)

Albeit I be

Unborn, undying, indestructible,

The Lord of all things living; not the less—

By Maya, by My magic which I stamp

On floating Nature-forms, the primal vast—

I come, and go, and come. (IV:6)

Hard it is

To pierce that veil divine of various shows

Which hideth Me; yet they who worship Me

Pierce it and pass beyond. (VII:14)

—Bhagavad Gita (Arnold’s translation )