Chapter 32

Rama Is Raised From the Dead

“‘Now a certain man was sick, named Lazarus....When Jesus heard that, he said, This sickness is not unto death, but for the glory of God, that the Son of God might be glorified thereby.’ ” 1

Sri Yukteswar was expounding the Christian scriptures one sunny morning on the balcony of his Serampore hermitage. Besides a few of Master’s other disciples, I was present with a small group of my Ranchi students.

“In this passage Jesus calls himself the Son of God. Though he was truly united with God, his reference here has a deep impersonal significance,” my guru explained. “The Son of God is the Christ or Divine Consciousness in man. No mortal can glorify God. The only honour that man can pay his Creator is to seek Him; man cannot glorify an Abstraction that he does not know. The ‘glory’ or nimbus around the head of the saints is a symbolic witness of their capacity to render divine homage.”

Sri Yukteswar went on to read the marvellous story of Lazarus’ resurrection. At its conclusion Master fell into a long silence, the sacred book open on his knee.

“I too was privileged to behold a similar miracle.” My guru finally spoke with solemn unction. “Lahiri Mahasaya resurrected one of my friends from the dead.”

The young lads at my side smiled with keen interest. There was enough of the boy in me, too, to enjoy not only the philosophy but, in particular, any story I could get Sri Yukteswar to relate about his wondrous experiences with his guru.

“My friend Rama and I were inseparable,” Master began. “Because he was shy and reclusive, he chose to visit our guru Lahiri Mahasaya only during the hours between midnight and dawn, when the crowd of daytime disciples was absent. As I was Rama’s closest friend, he confided to me many of his deep spiritual experiences. I found inspiration in his ideal companionship.” My guru’s face softened with memories.

“Rama was suddenly put to a severe test,” Sri Yukteswar continued. “He contracted the disease of Asiatic cholera. As our master never objected to the services of physicians at times of serious illness, two specialists were summoned. Amidst the frantic rush of ministering to the stricken man, I was deeply praying to Lahiri Mahasaya for help. I hurried to his home and sobbed out the story.

“‘The doctors are seeing Rama. He will be well.’ My guru smiled jovially.

“I returned with a light heart to my friend’s bedside, only to find him in a dying state.

“‘He cannot last more than one or two hours,’ one of the physicians told me with a gesture of despair. Once more I hastened to Lahiri Mahasaya.

“‘The doctors are conscientious men. I am sure Rama will be well.’ The master dismissed me blithely.

“At Rama’s place I found both doctors gone. One had left me a note: ‘We have done our best, but his case is hopeless.’

“My friend was indeed the picture of a dying man. I did not understand how Lahiri Mahasaya’s words could fail to come true, yet the sight of Rama’s rapidly ebbing life kept suggesting to my mind: ‘All is over now.’ Tossing thus on alternating waves of faith and doubt, I ministered to my friend as best I could. He roused himself to cry out:

“‘Yukteswar, run to Master and tell him I am gone. Ask him to bless my body before its last rites.’ With these words Rama sighed heavily and gave up the ghost. 2

“I wept for an hour by his bedside. Always a lover of quiet, now he had attained the utter stillness of death. Another disciple came in; I asked him to remain in the house until I returned. Half dazed, I trudged back to my guru.

“‘How is Rama now?’ Lahiri Mahasaya’s face was wreathed in smiles.

“‘Sir, you will soon see how he is,’ I blurted out emotionally. ‘In a few hours you will see his body, before it is carried to the crematory grounds.’ I broke down and moaned openly.

“‘Yukteswar, control yourself. Sit calmly and meditate.’ My guru retired into samadhi . The afternoon and night passed in unbroken silence; I struggled unsuccessfully to regain an inner composure.

“At dawn Lahiri Mahasaya glanced at me consolingly. ‘I see you are still disturbed. Why didn’t you explain yesterday that you expected me to give Rama tangible aid in the form of some medicine?’ The master pointed to a cup-shaped lamp containing crude castor oil. ‘Fill a little bottle with oil from the lamp; put seven drops in Rama’s mouth.’

“‘Sir,’ I remonstrated, ‘he has been dead since yesterday noon. Of what use is the oil now?’

“‘Never mind, just do as I ask.’ My guru’s cheerful mood was incomprehensible to me; I was still in an unassuaged agony of bereavement. Pouring out a small amount of oil, I departed for Rama’s house.

“I found my friend’s body rigid in the death-clasp. Paying no attention to his ghastly condition, I opened his lips with my right index finger; and managed, with my left hand and the help of the cork, to put the oil drop by drop over his clenched teeth. As the seventh drop touched his cold lips, Rama shivered violently. His muscles from head to foot vibrated as he sat up wonderingly.

“‘I saw Lahiri Mahasaya in a blaze of light!’ he cried. ‘He shone like the sun. “Arise, forsake your sleep,” he commanded me. “Come with Yukteswar to see me.’ ”

“I could scarcely believe my eyes when Rama dressed himself and was strong enough after that fatal sickness to walk to the home of our guru. There he prostrated himself before Lahiri Mahasaya with tears of gratitude.

“The master was beside himself with mirth. His eyes twinkled at me mischievously.

“‘Yukteswar,’ he said, ‘surely henceforth you will not fail to carry with you a bottle of castor oil. Whenever you see a corpse, just administer the oil. Why, seven drops of lamp oil must surely foil the power of Yama!’

“‘Guruji, you are ridiculing me. I don’t understand; please point out the nature of my error.’

“‘I told you twice that Rama would be well; yet you could not fully believe me,’ Lahiri Mahasaya explained. ‘I did not mean the doctors would be able to cure him; I remarked only that they were in attendance. I didn’t want to interfere with the physicians; they have to live, too.’ In a voice resounding with joy, my guru added, ‘Always know that the omnipotent Paramatman can heal anyone, doctor or no doctor.’

“‘I see my mistake,’ I acknowledged remorsefully. ‘I know now that your simple word is binding on the whole cosmos.’ ”

As Sri Yukteswar finished the awesome story, one of the Ranchi lads ventured a question that, from a child, was doubly understandable.

“Sir,” he said, “why did your guru send castor oil?”

“Child, giving the oil had no special meaning. Because I had expected something material, Lahiri Mahasaya chose the nearby oil as an objective symbol to awaken my greater faith. The master allowed Rama to die, because I had partially doubted. But the divine guru knew that inasmuch as he had said the disciple would be well, the healing must take place, even though he had to cure Rama of death, a disease usually final!”

Sri Yukteswar dismissed the little group, and motioned me to a blanket seat at his feet.

“Yogananda,” he said with unusual gravity, “you have been surrounded from birth by direct disciples of Lahiri Mahasaya. The great master lived his sublime life in partial seclusion, and steadfastly refused to permit his followers to build any organisation around his teachings. He made, nevertheless, a significant prediction.

“‘About fifty years after my passing,’ he said, ‘an account of my life will be written because of a deep interest in yoga that will arise in the West. The message of yoga will encircle the globe. It will aid in establishing the brotherhood of man: a unity based on humanity’s direct perception of the One Father.’

“My son Yogananda,” Sri Yukteswar went on, “you must do your part in spreading that message, and in writing that sacred life.”

Fifty years after Lahiri Mahasaya’s passing in 1895 culminated in 1945, the year of completion of this present book. I cannot but be struck by the coincidence that the year 1945 has also ushered in a new age—the era of revolutionary atomic energies. All thoughtful minds turn as never before to the urgent problems of peace and brotherhood, lest the continued use of physical force banish all men along with the problems.

Though the works of the human race disappear tracelessly by time or bomb, the sun does not falter in its course; the stars keep their invariable vigil. Cosmic law cannot be stayed or changed, and man would do well to put himself in harmony with it. If the cosmos is against might, if the sun wars not in the heavens but retires at dueful time to give the stars their little sway, what avails our mailed fist? Shall any peace come out of it? Not cruelty but goodwill upholds the universal sinews; a humanity at peace will know the endless fruits of victory, sweeter to the taste than any nurtured on the soil of blood.

The effective League of Nations will be a natural, nameless league of human hearts. The broad sympathies and discerning insight needed for the healing of earthly woes cannot flow from a mere intellectual consideration of human diversities, but from knowledge of men’s deepest unity—kinship with God. Toward realization of the world’s highest ideal—peace through brotherhood—may yoga, the science of personal communion with the Divine, spread in time to all men in all lands.

Though India possesses a civilisation more ancient than that of any other country, few historians have noted that her feat of survival is by no means an accident, but a logical incident in the record of devotion to the eternal verities that India has offered through her best men in every generation. By sheer continuity of being, by intransitivity before the ages (can dusty scholars truly tell us how many?), India has given the worthiest answer of any people to the challenge of time.

The Biblical story of Abraham’s plea to the Lord 3 that the city of Sodom be spared if ten righteous men could be found therein, and the Divine Reply: “I will not destroy it for ten’s sake,” gains new meaning in the light of India’s escape from oblivion. Gone are the empires of mighty nations, skilled in the arts of war, that once were India’s contemporaries: ancient Egypt, Babylonia, Greece, Rome.

The Lord’s answer clearly shows that a land lives, not in its material achievements, but in its masterpieces of man.

Let the divine words be heard again, in this twentieth century, twice dyed in blood ere half over: No nation that can produce ten men who are great in the eyes of the Unbribable Judge shall know extinction.

Heeding such persuasions, India has proved herself not witless against the thousand cunnings of Time. Self-realized masters in every century have hallowed her soil. Modern Christlike sages, like Lahiri Mahasaya and Sri Yukteswar, rise up to proclaim that a knowledge of yoga, the science of God-realization, is vital to man’s happiness and to a nation’s longevity.

Very scanty information about the life of Lahiri Mahasaya and his universal doctrine has ever appeared in print. 4 For three decades in India, America, and Europe I have found a deep and sincere interest in his message of liberating yoga; a written account of the master’s life, even as he foretold, is now needed in the West, where lives of the great modern yogis are little known.

Lahiri Mahasaya was born on September 30, 1828, into a pious Brahmin family of ancient lineage. His birthplace was the village of Ghurni in the Nadia district near Krishnanagar, Bengal. He was the only son of Smt. Muktakashi, second wife of the esteemed Gaur Mohan Lahiri (whose first wife, after the birth of three sons, had died during a pilgrimage). The boy’s mother passed away during his childhood. We have little information about her, except a revealing fact: she was an ardent devotee of Lord Shiva, scripturally designated as the “King of Yogis.”

The boy, whose full name was Shyama Charan Lahiri, spent his early years at the ancestral home in Ghurni. At the age of three or four he was often observed sitting under the sands in a certain yoga posture, his body completely hidden except for the head.

The Lahiri estate was destroyed in the winter of 1833, when the nearby Jalangi River changed its course and disappeared into the depths of the Ganges. One of the Shiva temples founded by the Lahiris went into the river along with the family home. A devotee rescued the stone image of Lord Shiva from the swirling waters and placed it in a new temple, now well known as the Ghurni Shiva Site.

Gaur Mohan Lahiri and his family left Ghurni and became residents of Banaras, where the father immediately erected a Shiva temple. He conducted his household along the lines of Vedic discipline, with regular observance of ceremonial worship, acts of charity, and scriptural study. Just and open-minded, however, he did not ignore the beneficial current of modern ideas.

The boy Lahiri took lessons in Hindi and Urdu in Banaras study groups. He attended a school conducted by Joy Narayan Ghosal, receiving instruction in Sanskrit, Bengali, French, and English. Applying himself to a close study of the Vedas, the young yogi listened eagerly to scriptural discussions by learned Brahmins, including a Mahratta pundit named Nag-Bhatta.

Shyama Charan was a kind, gentle, and courageous youth, beloved by all his companions. With a well-proportioned, healthy, and powerful body, he excelled in swimming and in many feats of manual skill.

In 1846 Shyama Charan Lahiri was married to Srimati Kashi Moni, daughter of Sri Debnarayan Sanyal. A model Indian housewife, Kashi Moni cheerfully performed her home duties and observed the householder’s obligation to serve guests and the poor. Two saintly sons, Tincouri and Ducouri, and two daughters blessed the union. At the age of twenty-three, in 1851, Lahiri Mahasaya took the post of accountant in the Military Engineering Department of the British government. He received many promotions during the time of his service. Thus not only was he a master before God’s eyes but also a success in the little human drama in which he played a humble role as an office worker in the world.

At various times the Engineering Department transferred Lahiri Mahasaya to its offices in Gazipur, Mirjapur, Naini Tal, Danapur, and Banaras. After the death of his father, the young man assumed responsibility for the members of his entire family. He bought for them a home in the secluded Garudeswar Mohulla neighborhood of Banaras.

It was in his thirty-third year that Lahiri Mahasaya 5 saw fulfilment of the purpose for which he had reincarnated on earth. He met his great guru, Babaji, near Ranikhet in the Himalayas, and was initiated by him into Kriya Yoga .

Yogoda Satsanga Society of India Ashram and Retreat in the Himalayan foothills near Dwarahat. In the hills nearby is the cave where Mahavatar Babaji dwelt for a time, and where, in 1861, he gave Kriya Yoga initiation to Lahiri Mahasaya, thus reviving the ancient lost spiritual science for the modern world (see chapter 34).

This auspicious event did not happen to Lahiri Mahasaya alone; it was a fortunate moment for all the human race. The lost, or long-vanished, highest art of yoga was again being brought to light.

As the Ganges 6 came from heaven to earth, in the Puranic story, offering a divine draught to the parched devotee Bhagirath, so in 1861 the celestial river of Kriya Yoga began to flow from the secret fastnesses of the Himalayas into the dusty haunts of men.

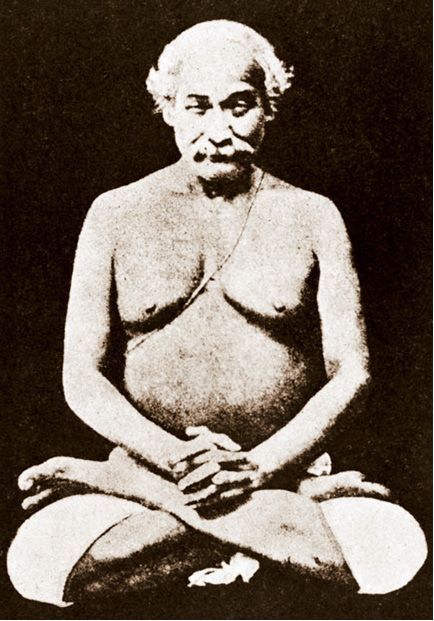

“I am Spirit. Can your camera reflect the Omnipresent Invisible?” After several unsuccessful exposures of the film in which no image of Lahiri Mahasaya could be captured, the Yogavatar finally permitted his “bodily temple” to be photographed. “The master never posed for another picture; at least, I have seen none,” wrote Paramahansaji.

1 John 11:1–4 (Bible).

2 A cholera victim is often rational and fully conscious right up to the moment of death.

3 Genesis 18:23–32 (Bible).

4 A short biography in Bengali, Sri Sri Shyama Charan Lahiri Mahasaya, by Swami Satyananda, appeared in 1941. From its pages I have translated a few passages for this section on Lahiri Mahasaya.

5 The Sanskrit religious title of Mahasaya means “large-minded.”

6 The waters of Mother Ganga, holy river of the Hindus, have their origin in an icy cave of the Himalayas amidst the eternal snows and silences. Down the centuries thousands of saints have delighted in remaining near the Ganges; they have left along its banks an aura of blessing.

An extraordinary, perhaps unique, feature of the Ganges River is its unpollutability. No bacteria live in its changeless sterility. Millions of Hindus, without harm, use its waters for bathing and drinking. This fact is baffling to modern scientists. One of them, Dr. John Howard Northrop, co-winner of the Nobel Prize for chemistry in 1946, recently said: “We know that the Ganges is highly contaminated. Yet Indians drink out of it, swim in it, and are apparently not affected.” He added, hopefully: “Perhaps bacteriophage [the virus that destroys bacteria] renders the river sterile.”

The Vedas inculcate reverence for all natural phenomena. The devout Hindu well understands the praise of St. Francis of Assisi: “Blessed be my Lord for our Sister Water, so useful, humble, chaste, and precious.”