The triumph of advertising in the culture industry is that consumers feel compelled to buy and use its products even though they see through them.2

Sixty years after its original publication, Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno’s Dialektik der Aufklärung resonates uncannily with our times. It is as if the central motifs of their bleak and horrifying diagnosis of the culture industry ring as true today as ever before. While Horkheimer and Adorno’s analysis of audience demand and reception dynamics is mostly regarded as antiquated by contemporary critics, this essay argues for the continued relevance of their indictment of culture under the (oppressive) authority of monopoly capital. In particular, the essay traces an emergent Schulterschluss between commercial and political power, with a special interest in the involvement of the music industry and the media conglomerates. This is not to say that contemporary America operates under the identical rules and constraints of the America of the 1940s. It does not. Nor is it to argue that capitalist America essentially approximates fascism as Horkheimer and Adorno sometimes imply. The opening arguments of “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception,” for example, are predicated on this fundamental similarity: “Even the aesthetic activities of political opposites are one in their enthusiastic obedience to the rhythm of the iron system. The decorative industrial management of buildings and exhibition centers in authoritarian countries are much the same as anywhere else.”3 Though useful as a polemical gesture, this linkage is overdrawn. Unlike fascist Germany, for instance, the current system operates within a framework of a democracy in the West, and, to a good measure, on the basis of a free market. Still, for all the immediately evident differences, Horkheimer and Adorno’s analysis has relevance to the post-Cold War period: a time when the world’s music has increasingly come under the control of a qualitatively and quantitatively new kind of corporate machinery.

Due to the extreme concentration of ownership of the mass media in recent years, the culture industry has become a major site of centralized power in the twenty-first century. Recorded music, for example, is the most concentrated global media market today: five leading firms — PolyGram, EMI, Warner Music Group (a unit of AOL Time Warner), Sony, BMG, and Universal Music Group (a unit of Vivendi) — are estimated to control between 80 and 90 percent of the global market.4 Most of these companies belong to larger conglomerates, which permits company-wide cross-promotions to bolster sales. Time Warner, for instance, owns magazines, book publishing houses, film studios, television networks, cable channels, retail stores, libraries, sports teams, and so on. Since the passing of the 1996 Telecommunications Act, radio too has become vertically concentrated and horizontally integrated to an unprecedented degree: Clear Channel Communications and Viacom alone control over 40 percent of the U.S. radio market. Today, Clear Channel is the world’s largest broadcaster, concert promoter, and billboard advertising firm.5 These companies are also connected to one another in a manner that implies a cartel-like arrangement. For instance, Disney has equity joint ventures, equity interests, or long-term exclusive strategic alliances with Bertelsmann, NBC, TCI, Kirch, Hearst, Dream Works, Canal Plus, America Online, and so on. So, just as Disney has interests in Bertelsmann, Bertelsmann has interests in Disney and much more.

This essay argues that media cross-ownership and joint ventures tend to reduce competition, lower risk, and increase profits. This, in turn, has forced musical production to succumb to the advertising, marketing, styling, and engineering techniques of increasingly uniform and narrow profit-driven criteria. Far from reflecting the public’s choices, Horkheimer and Adorno would link such musical production with the “technical and personnel apparatus which, down to its last cog, itself forms part of the economic mechanism of selection.”6 Today this pertains to an unprecedented degree. Under the rubric of various “organizational structures,” “production systems,” and “portfolio management techniques,” corporate strategies provide ever more ways of rationalizing and monitoring the activities of producers and consumers alike.7 Niche markets formulated in corporate headquarters exert an untold influence on the acquisition policies, the production and distribution practices, and the musical styles adopted by performers. Although (as Keith Negus argues) there has been a concurrent decentralization of many aspects of corporate decision making, today the marketing branch of record companies no longer functions in a merely administrative role. Instead, through intricate applications of management theory — supervising and measuring data — marketers settle priorities, make aesthetic judgments, and select musical forms. Horkheimer and Adorno’s argument anticipates this integration of cultural decision making and corporate ideology no less than the interconnected structure of corporate power. The argument further points out how culture is ultimately subordinated to the demands of the most powerful corporations.

In our age the objective social tendency is incarnate in the hidden subjective purposes of company directors, the foremost among whom are in the most powerful sectors of industry — steel, petroleum, electricity, and chemicals.… [Culture monopolies] cannot afford to neglect their appeasement of the real holders of power if their sphere of activity in mass society … is not to undergo a series of purges. The dependence of the most powerful broadcasting company on the electrical industry, or of the motion picture industry on the banks, is characteristic of the whole sphere, whose individual branches are themselves economically interwoven.8

Predictably perhaps, the chief executives of today’s large record labels often have no musical or cultural background. The head of Universal Vivendi, Jean René Fourtou, was previously in pharmaceuticals; while the head of Bertelsmann, Gunter Thielen, previously managed the company’s printing and industrial operations.

Although some writers recognize the constitutive role of monopoly capital in music’s production, most recent mediation analysis in musicology has tended to cohere around purely cultural categories such as gender relations, modalities of place, ethnicity, racial labels, age, religious affiliations, political allegiances, sexual codes and sexuality, and so on. Indeed, it is the hermeneutics of music’s heterogeneous and much contested cultural arena that buttresses a renewed faith in the progressive political efficacy of musicology’s new historicist approaches at the turn of the twenty-first century. In other words, this new musicology grounds its progressive claims in the rejection of grand, quasievolutionary narratives of music’s historical evolution and the concomitant embrace of differentiated histories with their own peculiar temporalities. These localized inquiries into traditionally excluded domains therefore carry a greater burden of passion and public mission than traditional history. For all its success in widening the musical/historical inquiry, however, the net result of the new musicological turn has been to fragment the field into plural dimensions. The high valuation of music’s partial histories, minority discourses, and local politics (not unlike the special interest nature of the structures lobbying for influence and profit in the political arena) has failed to prevent a paradoxical new totalization that marches in step with the ideological demands of late capitalism. That is, by rejecting all metanarratives of historical development, along with all totalizing notions of musical value, these nichelike musicological subfields can fail to reckon with the escalating control of unified corporate power on a global scale today. This is not to say these subfields actively serve corporate interests. On the contrary, much of this work is actively directed against the juggernaut of corporate power.

However, where the critical scholarship does acknowledge the constraints placed by the commercial system on the activities of those involved in the making and appreciation of music, it tends to highlight the moments when gaps and fissures appear in that system. These are moments when the circulation of musical commodities as well as the social valences and meanings assigned to various pieces, forms, and genres exceed those imprinted by the business structures that are their conditions of possibility. Again, this methodological orientation stresses the ways corporate cooptation is not total, noting how the emotional, sensual, and social investments in music escape the demands of the commercial sphere. Contemporary theories of mass consumption have therefore increasingly resisted the apocalyptic determinism attributed to the culture industry by Horkheimer and Adorno. Where the latter diminished the agency of the consumer (who passively identifies with false utopian dreams), contemporary theories have elevated it. By insisting on the unpredictable nature of musical consumption — via symbolic revisions and political uses not imagined by the industry — these theories tend to differentiate the scope and authority of the culture industry. While industry attempts to circumscribe the parameters of consumer desire, the argument goes, consumers’ purchasing choice in itself also opens space for resistance and empowerment. For example, the politics of rap emerge in a struggle conducted in the field of consumption, which lies outside the logic and grasp of any identifiable industry strategies;9 or postmodern art music offers challenging new forms that blur the boundaries between the elitist formality of art music and the commercial standardization of popular music;10 or salsa music circulates in a cultural matrix that articulates as much a critique as an embrace of the social conditions (especially the structural racism that marks the limits of American multiculturalism) that created it;11 and so on. While this kind of writing recognizes the mundane mediations of the music industries, it tends to stress strategies of resistance, subjective agency, and musical autonomy that emerge across a broader social field than Adorno and Horkheimer’s analysis will permit. In short, for these writers, music in cultural practice cannot be reductively translated and transformed into the logic of commodification. Although the following arguments will not directly refute or even contradict the work of cultural musicology on this issue, I would like to argue that nevertheless Horkheimer and Adorno’s scenario accurately captures important new developments in musical production and consumption; developments that, in turn, reflect a mutation in capitalism after the Cold War.

The tendency for mass-produced music to stabilize hegemonic ideologies via stereotypical forms and schematic formulae has undergone a qualitative shift in recent years. Opportunities for commodification have massively expanded. Given the scope of the problem on the side of production today, it is symptomatic that resistance should be confined to the side of consumption alone. As a critical praxis, this lopsided condition itself betrays a blocked dialectic. This is not to reduce the politics of consumption to irrelevance. Indeed, the dynamic between corporate desires and listeners’ desires is inherently complex and capricious. To cope with this, the music industry, now part of an oligopolistic multibillion dollar mass culture industry, has differentiated its markets to correspond precisely with the identitarian categories of race, gender, nationality, class, and religion that broadened current debates in musicology and cultural studies. In fact, the pluralism of these collective identities provides a convenient palette of marketing categories for the music industry. Along with innovations in communication technologies as well as flexibility in production and distribution techniques, such co-opted pluralism has led to an explosion of musical variety and productivity. Of course, the variety of music available to the American consumer today is practically immeasurable. Yet, the apparently erratic turbulence of musical production is, in reality, subordinated and contained by awesomely consolidated corporate structures; likewise, its dissemination is hierarchically guided by highly distinctive commercial criteria. As radio stations and record companies merge, for instance, they diversify their holdings by rationalizing their portfolio of labels, genres, and artists by dividing them into discrete strategic business units. This renders visible the cost and the profit of each genre division, which, in turn, determines the allocation of finances between and within them. Far from opening to genuine complexities and resonances of musical expression, the diversity of the culture industry amounts to a matrix of detached indicators used to stabilize, predict, and contain musical production. Concomitantly, from the perspective of the industry, the dynamics of consumption are reduced to the logic of the bottom line. Again, Horkheimer and Adorno envisaged this condition in their assessment of the culture industry: “Consumers appear as statistics on research organization charts, and are divided by income groups into red, green, and blue areas; the technique is that used for any type of propaganda.”12

Today the rationalization of the bottom line via genre containers has broadened its technological reach to include the electronic monitoring of CD sales, popularity ratings, and radio airplay statistics. Poor performances can involve layoffs, dropping artists, or even closing down divisions. In many cases, the tendency is increasingly to concentrate resources on profitable sectors and then to diminish those sectors to a category of profitable stars.13 The calculated strategy to reduce risk inevitably reduces investment in those genres and forms that prize unpredictability and experimentation. Divisions whose profitability profile is substandard are either abandoned entirely or they undergo a kind of inner metamorphosis to reflect a financial logic produced by statistical data. For example, when in 1989 Warner Music purchased the classical music Tulda label (in Germany) and Erato (in France) Warner divested itself of various genres and artists and concentrated instead on a few lucrative star artists, like José Carreras. As Benjamin Boretz wryly remarks: “To make it in today’s classical music market, you have to be Yo-Yo-Ma: I do not mean this metaphorically, but literally!”14 Forced to reckon with the financial turnover of popular music divisions, classical music divisions increasingly absorb the promotional characteristics of the former into their products. Thus classical performers are marketed as pop artists (such as Charlotte Church, Sarah Brightman, Nigel Kennedy, and, more recently, Renée Fleming) or crossover collaborations (such as Yo-Yo-Ma performing Appalachian melodies with Mark O’Connor or Placido Domingo singing popular tunes with Dionne Warwick); while classical composers are packaged in collections of greatest hits and thematic albums (such as compilations centered around relaxation, gay composers, Christmas, or pop opera). The pop opera band Amici Forever, for example, proudly market themselves with the slogan, “Think classical singing with a pop aesthetic.”15 Corporate strategies may appear to be a driving force behind an explosive diversity of musical modalities, but these new marketing slogans are rigidly subordinated to the same logical management of facts, figures, and statistics. Unorthodox and oppositional musical forms give way to niche-based formularism.

In this hypercommercialized setting, advertising becomes the very condition of possibility for music; and, concomitantly, music gradually absorbs the procedures of advertising. According to Horkheimer and Adorno, these procedures are absorbed into the very structure of the industry’s products: “The assembly-line character of the culture industry, the synthetic, planned method of turning out its products … is very suited to advertising: the important individual points, by becoming detachable, interchangeable, and even technically alienated from any connected meaning, lend themselves to ends external to the work.”16 Music’s diminished role as a mechanism for product promotion today takes many forms. The most obvious case is the sponsorship of music’s institutional space. For example, against a backdrop of shrinking donations from arts foundations to arts groups, the nation’s cultural space is increasingly dominated by corporate control. Just as the Selwyn Theatre on 42nd Street, New York, was refurbished and renamed the American Airlines Theater in the 1990s, Jazz at Lincoln Center has named one of its new 140-seat performance venues Dizzy’s Club Coca-Cola in return for a $10 million donation from the soft drink giant. Although Wynton Marsalis, artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center, denies the company will influence artistic choices in the venue, Coca-Cola clearly benefits from the association with jazz. In the words of Charles Fruit, Senior Vice President of Worldwide Media and Alliances at Coca-Cola: “If you think about jazz and the Coca-Cola Company, each has a dual personality. Each is uniquely American. At the same time, wherever you go around the world, the public views it as their music or their beverage. We saw that interesting parallel between our brand and jazz.”17 Coca-Cola hitches a ride on a shared cultural legacy — an authentic and cherished public scene — so as to infuse its brand with an aura of authenticity. In short, jazz “adds value” to the drink.

Matthew McAllister describes the effects of this mechanism: “While elevating the corporate, sponsorship simultaneously devalues what it sponsors.… The sporting event, the play, the concert and the public television program become subordinate to promotion because, in the sponsor’s mind and in the symbolism of the event, they exist to promote. It is not Art for Art’s Sake as much as Art for Ad’s Sake. In the public’s eye, art is yanked from its own separate and theoretically autonomous domain and squarely placed in the commercial.… Every time the commercial intrudes on the cultural, the integrity of the public sphere is weakened because of the obvious encroachment of corporate promotion.”18 Instead of tolerating advertising as a commercial interruption to cultural events and spaces, the structural need for corporate sponsorship is today becoming the norm. Thus, instead of emphasizing the credit Coca-Cola receives for its donation, the cultural community increasingly feels relief and gratitude for Coca-Cola’s generosity in getting the Jazz at Lincoln Center project off the ground.19 This is not a problem of collective false consciousness as much as it is a problem of censorship and restriction, the ideological consequence of privatizing communal cultural spaces. Naomi Klein, for example, illustrates the point with a case in 1997, when the sponsors of the du Maurier Downtown Jazz festival in Toronto aggressively removed all critical material from the venue. In the words of Klein, “When any space is bought, even if only temporarily, it changes to fit its sponsors.”20 Concomitantly, when the sponsoring corporation no longer benefits from the cultural aura inscribed in an artistic genre or style, it simply cuts its funding. In May 2003, for instance, the fossil-fuel giant Chevron-Texaco unilaterally decided, after sixty-three years, to stop financing its Saturday afternoon broadcasts of opera from the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City.21 Under the sway of corporate efficiencies and revenue opportunities, the relationship between culture and the corporate sector is rendered inherently capricious.

This is not to say all forms of corporate sponsorship compromise artistic autonomy or critical import. Conservative academic defenses of commercial culture maintain that the market economy in fact generates creativity and thus contributes to artistic diversity. Tyler Cowen, Economics Professor at George Mason University, for example, writes: “Material wealth helps relax external constraints on internal artistic creativity, motivates artists to reach new heights, and enables a diversity of artistic forms and styles to flourish.”22 Cowen’s argument rests on a number of premises and generalizations entirely beholden to an absolute belief in the goodness of the market economy. The second sentence of his book In Praise of Commercial Culture reads, “Artists work to achieve self-fulfillment, fame, and riches.”23 This already disembodied and generalized idea gradually reduces simply to the quest for riches (“love of money,” “pursuit of profits,” etc.) as the book gets underway.24 In support of his theory of creativity, Cowen offers a faux history of Western music through the essentialized lens of pecuniary incentives and returns. Thus, writes Cowen, “The artists of the Italian Renaissance were businessmen first and foremost;” likewise, “Bach, Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven were all obsessed with earning money through their art;” and, again, likewise, “The British ‘punk violinist’ Nigel Kennedy has written: ‘I think if you’re playing music or doing art you can in some way measure the amount of communication you are achieving by how much money it is bringing in for you and for those around you.”25 As artists driven by pecuniary interests seek to avoid duplicating older styles and media, Cowen ties commercialism directly to “forces for innovation” in music.26 Moreover, argues Cowen, commercial culture encourages political radicalism: “Like Mozart,” he writes, “Beethoven used his financial independence to flirt with politically radical ideas. Mozart had set a precedent with the Marriage of Figaro, which lampooned the aristocracy…. Beethoven went further with his opera Fidelio, a paean to liberty and a critique of unjust government imprisonment.”27 Using the logic of the cultural Cold War, Cowen argues that American rock stands for freedom and individualism: The Soviet apparatchiks (who outlawed rock) “understood that rock was pro-capitalist, pro-individualist, consumerist, and opposed to socialism and state control.”28 While Cowen’s devotion to the market holds out hope for flourishing creative individualism as well as political freedom and even political radicalism in our times, the empirical record suggests otherwise. Indeed, as I will show, Cowen’s position cannot be sustained across the terrain of either music or politics.

It is important of course to acknowledge that musical expression has always been more or less dependent on patronage and financial backing, but it is equally important to acknowledge that the paradigm of music’s corporate sponsorship today is undergoing a qualitative transformation. Popular musicians have long worked closely with the commercial music industry. For example, since the early days of radio, musicians have advertised products, sung jingles, signed deals with sponsoring corporations and record companies, and so on. In the 1980s alone Coca-Cola recruited a host of stars (ranging from David Bowie and George Michael to Tina Turner and Whitney Houston) to sing in its advertisements. More recently, Sting’s music, like Pete Townsend’s The Who songs, advertise luxury cars. Even John Lennon’s Beatles song “Revolution” — a song “filled,” in John Densmore’s words, “with passionate citizens expressing their First Amendment right to free speech” — is used to sell Nike shoes.29 The payoff can be staggeringly lucrative. Densmore has repeatedly vetoed offers to use The Doors songs for commercial advertising: $50,000 for “When the Music’s Over,” from Apple Computers; $75,000 for “Light My Fire,” from Buick, $3 million for “Break on Through,” from an Internet company.30 Likewise, when it comes to concert productions today, corporate brands have become integrated with the concert experience. The clothing company, Tommy Hilfiger, seeking to associate itself with rap- and rock-oriented rebellion, sponsored the Rolling Stones’ 1997 “Bridges to Babylon” tour.31 In order to seek out consumer loyalties that far exceed the product being advertised, companies increasingly co-opt popular culture.

Yet, the relationship between musicians and the products they advertise is gradually shifting. Naomi Klein has diagnosed this trend in her book No Logo. For example, the advertisement campaign for the Stones’ 1999 “No Security” tour depicted Tommy Hilfiger models in the foreground watching the band in the background. In Klein’s words, “The tagline was ‘Tommy Hilfiger Presents the Rolling Stones No Security Tour” — though there were no dates or locations for any tour stops, only the addresses of flagship Tommy stores.”32 Klein argues that power relations between culture and sponsorship have been dangerously reversed in this dynamic; “the brand is the event’s infrastructure; the artists are its filler.”33 Thus, in the summer of 2003, Sean “ P. Diddy” Combs (the self-proclaimed master of the remix, integrating styles as diverse as hip-hop, pop, soul, rap, and underground) launched a new product line for Coca-Cola. The new drink was named after a musical technique: Sprite “Remix.” Similarly, musicians like the Backstreet Boys, Macy Gray, and Rufus Wainwright are fully integrated with branded aesthetics. For example, Wain-wright’s sales soared after he appeared in a Gap commercial.34 Likewise, sales on Sting’s 1999 album, Brand New Day, were poor until he appeared in an ad for Jaguar singing songs from the album.35

Mass marketing and advertising have infiltrated the world of music to an unprecedented degree. Where wholesale branding has not penetrated the very composition of songs, commercial products are nonetheless promoted through them. Product placement, the surreptitious placement of commodities inside popular songs or programs has become a burgeoning sector of the economy. In Los Angeles, for example, there are dozens of consultancies linking music and film producers to marketers.36 Laurie Mazur describes the cost of product placement in Hollywood films: “$10,000 to have the product appear in the film, $30,000 to have a character hold the product. In Other People’s Money, Danny DeVito holds a box of donuts, looks into the case and says: ‘If I can’t depend on Dunkin’ Donuts, who can I depend on?’”37 Product placement is ubiquitous in music videos. Kylie Minogue advertises American Express, Jay Z advertises Range Rover and Rolex, and so on. Products even generate a song’s very substance: In the spirit of Run DMC’s “My Adidas,” for example, Busta Rhymes sings a tribute to Courvoisier cognac in his song “Pass the Courvoisier”; similarly, Tweet basically presents a lyrical consumer report for Motorola mobile phones in her video “Call Me.” Erik Parker points out that Verizon recruited Tweet to endorse its wireless services at the same time “Call Me” was being aired.38 Horkheimer and Adorno’s claim that “advertising and the culture industry merge technically as well as economically” has gathered additional resonance in these times: music videos are gradually becoming interchangeable with commercials.39 The day is probably imminent when artists will need corporate endorsements and advertisements to defray costs of production before they even begin making a video or recording. The reversal of aesthetic priorities matches the reversal of communal priorities in the American social landscape at large. For example, in Louisville, Kentucky, WHAS paid the local community for broadcast rights to a balloon festival during Derby week. When Clear Channel bought the station, it demanded the community pay the corporation instead. Thus, corporate sponsorship and marketing, far from interrupting the flow of autonomous communal or musical activity, becomes the structural condition of possibility for communal events and music making.

This infrastructural reversal is dramatically exacerbated in the context of massive media consolidation. For Adorno, the intimate integration of popular music with such “highly centralized economic organization” ultimately leads to musical standardization and conformism.40 Arguably, this is contradicted by the seemingly erratic proliferation of diverse musical genres today. Yet, new forms of standardization and conformism are emerging precisely in the most consolidated sectors of corporate control. One consequence of mergers and acquisitions is that small, independent, and nonprofit labels are forced to compete against overwhelmingly proliferated production and distribution resources and, as a result, routinely shut down. In April 2003, for example, Composers Recordings Inc. (CRI), whose catalog centers around adventurous recordings by maverick composers, closed its offices. (Some tiny labels, like Hyperion and CPO, continue to thrive, potentially the dialectical backlash to the new corporate centralization.) Another consequence of mergers and acquisitions is that the surviving holdings are subject to considerable rationalization and systematization. In his discussion of “imitation” in “On Popular Music” Adorno writes:

The most successful hits, types, and “ratios” between elements were imitated, and the process culminated in the crystallization of standards. Under centralized conditions such as exist today … standards have become “frozen.” That is, they have been taken over by cartelized agencies, the final results of a competitive process, and rigidly enforced upon material to be promoted. The original patterns that are now standardized evolved in a more or less competitive way. Large-scale economic concentration institutionalized the standardization, and made it imperative. As a result, innovations by rugged individualists have been outlawed.41

Adorno’s words may sound exaggerated but they are in fact oddly appropriate today. As companies extend their distributional reach, they tend to promote and encourage musical repertoires with a “general” appeal. As Ann Chaitovitz, National Director of Sound Recordings, American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (AFTRA) says, “radio consolidation has resulted in less variety of music being played on the radio, shorter playlists, homogenization of playlists, and less local music being broadcast.”42 While the appeal to general taste seems neutral and unproblematic at first glance (genuinely popular at best; somewhat bland at worst), music under these conditions is in fact subject to highly distinctive aesthetic codes and cultural judgments. Consider the priorities articulated by David McDonagh, a senior staff member of Poly-Gram’s International division: “The basic kind of music that has broad appeal internationally is kind of, like, pop music ballads. Ballads always work. It doesn’t matter if it’s Whitney Houston, Mariah Carey, Bon Jovi or whoever it happens to be.”43 Thus, music with a slow ballad structure coupled with a distinctive melodic profile, for example, tends to receive inflated investment and resources. Such songs are easily translated and transformed into mega-hits across the globe: a condition that bears out Adorno’s suspicion in “The Radio Symphony” essay that “the actual mechanization of radio transmission” is constitutively linked to “the quasi expressive ballads with which our radio programs are jammed.”44

Executives in the business often refer to a song’s distinctive attention-grabbing moment as the “money note.” John Seabrook describes the expensive-sounding moment in the context of commercial ballads: “The money note is the moment in Whitney Houston’s version of the Dolly Parton song ‘I Will Always Love You’ at the beginning of the third rendition of the chorus: pause, drum beat, and then ‘Iiiiiieeeeeeiiieeii will always love you.’ It is the moment in the Céline Dion song from ‘Titanic,’ ‘My Heart Will Go On’: the key change that begins the third verse, a note you can hear a hundred times and it still brings you up short in the supermarket and transports you from the price of milk to a world of grand romantic gesture — ‘You’re here/There is nuthing to fear’.”45 Adorno would refer to these musical moments as “pseudo-individualization,” a mechanism to instill “the halo of free choice or open market on the basis of standardization itself.”46 In particular, Adorno would link these kinds of glamorous expressive outbursts with the manipulations associated with advertising, comparable to the “radio barker who implores his unseen audience not to fail to sample wares and does so in tones which arouse hopes beyond the capacity of the commodity to fulfill.”47 Adorno continues, “All glamor is bound up with some sort of trickery. Listeners are nowhere more tricked by popular music than in its glamorous passages. Flourishes and jubilations express triumphant thanksgiving for the music itself — a self-eulogy of its own achievement in exhorting the listener to exultation and of its identification with the aim of the agency in promoting a great event.”48

Adorno connects this kind of manipulative mechanism with the hierarchies of postcompetitive capitalism. Not surprisingly, as my discussion of Clear Channel Communications will show, music with these kinds of standardized ingredients, coupled with glamorous pseudodifferentiations, also gains considerable airplay on radio channels whose ownership is most consolidated. The point here is that far from reflecting a neutral and general taste in music, this stabilized aesthetic tends to mediate the tastes of a highly particular demographic, namely, the social sector with disposable income: predominantly white, middle-class, heterosexual, eighteen- to forty-five-year-old males. When unfettered economic criteria drive aesthetic decisions, it stands to reason that radio play, media coverage, and sales will be directed toward the most lucrative factions of society. The current popularity of standardized fare, such as diluted alternative rock bands like Creed (recently reconstituted under the name Alter Bridge), Puddle of Mudd, Nickleback, and 3 Doors Down, must be understood in this context. Even mainstream publications recognize the monotony of concentrated radio and the need for innovation and diversity on the airwaves. Writing for Newsweek in May 2004, for example, David Gordon reports, “If you tuned out on rock music a few years ago because you just couldn’t stand to hear another Creed song, it’s time to come back to the flock … major-market radio, dominated by Clear Channel and drab rock acts like Nickelback … has bored listeners into experimentation.”49 As the trade publication Variety observed in 1999, “A huge wave of consolidation has turned music stations into cash cows that focus on narrow playlists aimed at squeezing the most revenue from the richest demographics.… Truth be told, in this era of megamergers, there has never been a greater need for a little diversity on the dial.”50 A 2002 study by the Future of Music Coalition (FMC) targeting the general population revealed that most Americans decisively favor less advertising on radio, less repetition of songs, less music boosted by record companies, more new music, and more airplay for local artists.51 Thus, the ideology of unfettered profit extends beyond purely economic analytic criteria into a highly selective ideology of cultural worth and aesthetic taste that is, according to this kind of study, largely out of sync with many citzens’ interests and tastes.

The ideological fallout is not limited to the sphere of culture alone. Indeed, music administered by the extraordinarily integrated culture industry is increasingly co-opted in service of official state policies. In other words, music, compromised by a commercial agenda, tends to become a carrier of political beliefs and values endorsed by the governing elite. This development is connected to various factors, some financial, others overtly political. For example, in the early 1970s a group of ultraconservative millionaires in the United States, who sought to promote right-wing thinking throughout the country, developed a multicapillaried reeducation project. This included the institution of conservative foundations (such as the Bradley Foundation, the Smith Richardson Foundation, Castle Rock [Coors] Foundation, etc.), the founding of national think tanks (including the Heritage Foundation, the American Enterprise Institute, Hoover Institution, Cato Institute, etc.) and, importantly, the acquisition of mass media outlets (radio stations, journals, newspapers, including the Washington Times and the Wall Street Journal).52 By the end of the 1990s conservative views dominated the airwaves. Television stations like Fox News not only raised right-wing thought to radical new heights, but, in tandem with views generated by like-minded think tanks, they also exerted a gravitational pull of conservatism on the entire media spectrum.53

Speaking more generally, there is often a direct financial interest in biased or false reporting. For example, although it is of vital interest to the citizenry, the five primary broadcasters (ABC, CBS, NBC, Fox, and CNN) rarely, if ever, report on the details of corporate contributions toward election campaigns. This is a reasonable omission if we consider, first, that this money is largely spent on those corporations in the form of advertisements and media consultation: Since the mid-1980s, spending on political advertisements has increased from $90 million to over a billion dollars. The omission is reasonable if we consider, second, that the benefits derived from such contributions include direct subsidies and tax breaks; and third, that donations to campaigns provide political leverage on policy decisions that favor corporate consolidation (such as the deregulation of the airwaves); and so on. Thus, the media empires are often used to promote corporate values and a conservative political agenda. With these corporations profiting directly from the political process that drives campaigns, the media is no longer suitable as a reliable messenger for political messages and information. Take MSNBC’s coverage on May 11, 2003: In a context of daily casualties (on both sides) in Iraq, MSNBC ran the winner of “Survivor” as the lead story. Tellingly perhaps, both stories operate within a similar ideological field of dialectical tensions, in this case curiously blending the inevitability of virile destiny with the blind chance of a gamble. For the purposes of this argument, however, it suffices to note how the media can overwhelm the public with irrelevant details and lure it into false debates.

Since most major media outlets (radio, television, the Internet, etc.) were pioneered as public services by the nonprofit sector with government subsidies, the general lack of public participation in the debate on media policy in the United States over the course of the twentieth century is alarming. Take the case of radio: The 1934 Communications Act established radio as a public resource managed according to a model of trusteeship by the federal government.

Broadcasters received a free slice of the radio spectrum in exchange for serving the “public interest, convenience and necessity.” The Act also included provisions to promote diversity and localism. In 1996, Congress passed the Telecommunications Act to replace the 1934 law. The principal aim of the 1996 law was to deregulate all communication industries. To the extent that the public was informed at all — the media covered the Telecommunications Act as a business technicality instead of a public policy story — it was assured that deregulation would intensify market competition and generate high-paying jobs. There was no public debate. As New York Congressman Jerrold Nadler pointed out at the 2003 Forum on FCC Ownership Rules, even in Congress the radio bill of 1996 received no informed debate; in fact, it was appended to a technical discussion involving long-distance carriers.54

Less than a decade after its passing into law, the effects of the Telecommunications Act have been extensive. Deregulation led to unprecedented merger activity, corporate concentration, and drastic downsizing. By 2003, two companies, Clear Channel Radio and the Infinity Broadcasting unit of Viacom, controlled almost half the nation’s airwaves and industry revenues. Before the passing of the Telecommunications Act, radio ownership was limited to only two stations in any market and no more than twenty AM and twenty FM stations nationwide. Clear Channel, whose radio stations grew from 40 to 1,240 stations in seven years, today reaches more than one third of the U.S. population (110 million listeners) a week and generates over $3 billion annually in revenues.55 Thus, instead of promoting it, deregulation has decreased competition. For example, Clear Channel’s ownership of stations in the most concentrated markets — KIIS-FM in Los Angeles, WHTZ and WKTU in New York, KHKS in Dallas, WXKS in Boston, WHYI in Miami, and so on — effectively gives a single company control of the Top-40 format.

Likewise, instead of providing jobs, deregulation has encouraged layoffs. Economies of scale produce efficiency by reducing expenses. Jenny Toomey, Executive Director of Future of Music Coalition, explains: “Radio runs on many fixed costs: Equipment, operations and staffing costs are the same whether broadcasting to one person or 1 million. Owners knew that if they could control more than one station in a local market, they could consolidate operations and reduce fixed expenses. Lower costs would mean increased profit potential.”56 Clear Channel developed a reputation in Wall Street for its Draconian cost cutting. One strategy for cutting costs is the aggressive elimination of jobs. Robert Unmacht, former publisher and editor of the M Street Journal, which tracks radio business, describes the effects of downsizing at Clear Channel: “The pressure is now on to do more with fewer people. Everything needs to show a profit yesterday.”57 Clear Channel has saved millions by eliminating scores of DJ positions. John London (a morning host on KCMG in Los Angeles), Jack Cole (a veteran talk-show host at WJNO in West Palm Beach), and various producers from the 460-station AMFM Network in Los Angeles were probably illegally fired when Clear Channel took over their respective radio stations.58 Clear Channel has centralized its bureaucratic operations, by programming its stations from regional, rather than local, locations. Today a single DJ broadcasts over many stations using enhanced digital editing to create the illusion of a local broadcast. The Clear Channel Radio blurb on the web, designed to appeal to investors, describes the technology enhancements used to create this illusion: “Clear Channel uses digital voice tracking and in-market feeds to deliver a sound that is live and local.… The result: Greater value for both advertisers and listeners.”59 Clear Channel’s assumed equivalence of interest between communities of listeners and advertisers is matched by the assumed equivalence between actual radio presenters and virtual ones. The business strategy is to dispense with genuine local broadcasting and actual live DJs and replace them with “a sound” thereof via a “voice tracking” technique. Voice tracking is a computer assisted system by which live radio is replaced by prerecorded voice segments between songs. Announcers, often living far away from the area in which they are being broadcast, are encouraged to pretend they are part of a local community.

Listening to WKTU in New York, for example, can be an illusionist experience: nameless voices from the “local” public briefly interrupt the endless flow of jingles, hook motives, and effects with flagrantly prefabricated requests, appraisals, greetings, and recorded dedication calls. Also, despite the slick pace and sound of the production, I have not infrequently heard DJs confusing promotional events (erroneously substituting a club party in Long Island for one in Orange County, for instance). The Wall Street Journal confirms my experience: “In Boise, [Clear Channel’s] KISS FM listeners heard a DJ named ‘Cabana Boy Geoff ’ Alan explain, ‘On Saturday night, me and Smooch, we were hanging out at the Big Easy…. Just thinking about it, I’m cracking up.’ In fact, as the Journal reported, Alan taped the program in San Diego, before the Saturday in question. He had never set foot in Boise all his life.…”60 Likewise, the Washington Post reports that talk show host Brian Wilson, “sits on his farm north of Baltimore and talks California politics with listeners on San Francisco’s KFSO. Wilson wakes up each day, fires up his Web browser and reads the morning San Francisco Chronicle online for the latest news from clear across the country … This is what passes for local radio these days.”61 Clear Channel’s claim to localism is essentially a fraud. In Dayton, Ohio, local Clear Channel stations no longer even report on the weather.62 Cutbacks in local staffing have resulted in a situation where radio listeners nationwide increasingly hear the same DJs. Randi West’s midday show, for example, has aired in Cincinnati, Ohio; Louisville, Kentucky; Des Moines, Iowa; Toledo, Ohio; Charleston, South Carolina; and Rochester, New York (Boehlert, 2001, 5); while Beverly Farmer has delivered traffic reports under various names (Alex Richards on WMZQ; Vera Bruptley on WJFK; Ginny Bridges; Lee McKenzie, and so on).63 Consolidation and cutbacks in staff can contradict the function and value of radio. In 2002, a train derailed in Minot, North Dakota, releasing a dangerous cloud of anhydrous ammonia. All six commercial stations in Minot are owned by Clear Channel. To no avail, local police tried to notify the citizenry by calling KCJB (the station designated to broadcast local emergencies): KCJB was being run by computer from afar, and three hundred people were hospitalized as a result.64 In short, at the expense of responsible local broadcasting, deregulation has cost jobs.

Finally, instead of promoting diversity, deregulation has promoted bland and homogenized fare. It is true that judgments of musical taste are, practically by definition, considered subjective and relative. Furthermore, in recent debates describing the negative effects of corporate consolidation, the prevalence of music is frequently invoked as a litmus test indicating a decline in public interest broadcasting per se. In other words, as a style-based medium built by advertising, music on corporate-owned media tends to cluster virtual communities that cannot be equated with physical communities serving a public sphere. Consumers’ taste is not identical to citizens’ interests and needs. In short, music — figured in terms of entertainment and lifestyle choices alone — diverts attention from issues of social interest and thus generates political apathy. News coverage on Clear Channel stations, for instance, has practically fallen away in recent years, giving way to predominantly music-based programming: is this an attempt to manufacture disinterest in public affairs? James L. Winston, Executive Director of the National Association of Black Owned Broadcasters, notes a similar tendency on Black Entertainment Television (BET). Winston points out that since the takeover by Viacom of BET, the single African-American cable channel, there has been a marked decline in public affairs programming and an increase in music videos.65 In No Logo, Naomi Klein too isolates music on MTV as the consummate site of fully branded media integration.66 Yet, what Klein’s analysis precisely reveals is the dramatic extent to which music in the age of synergy-driven production has been co-opted, exploited, compromised, and coerced to a commercial agenda. Therefore, far from sliding on the slippery slopes of subjective relativism, the matter of musical quality on the airwaves, free of commercial content, requires urgent attention.

Still, musical taste cannot be readily captured by the kind of “quantitative analysis,” such as the “empirical data” and “metrics,” demanded of interest groups presenting their cases to the FCC.67 In this context it is no small irony that, in defense of the content of their playlists, the music industries routinely invoke precisely the musical tastes and interests of their listeners as if these were established empirical facts.68 Despite the obstacles, the empirical record, in fact, points in a different direction from that portrayed by the industries. Consider Michael K. Powell’s redundant proconsolidation question in a New York Times article (“Fewer Media Owners, More Media Choices”): “Common ownership can lead to more diversity — what does the owner get for having duplicative products?”69 While it makes common sense at first glance, this viewpoint cannot be generally sustained: The enormous financial success of Starbucks Coffee, for instance, derives far less from its diversified product range than from its enormous horizontal reach. To demonstrate their interest in localism and diversity, media giants frequently cite quantitative figures on program formats. For example, David F. Poltrack, Executive Vice President, Research and Planning at CBS, indicates that the public is served by deregulation because of the sheer increase in television channels in the last decade.70 Similarly, Dennis Swanson, Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer of Viacom Television Stations Group, maintains that media consolidation has increased the actual number of minutes of programming devoted to local news.71 While this may be quantitatively true, it is essential to place in context the quality of that programming.

An obsession with hyperrationalist commercial discourse (which predictably eliminates qualitative assessments) besets the debate on diversity and localism in the music industries. The tendency toward bland and formulaic repetition is particularly pronounced in the domain of music. Horkheimer and Adorno argue that the advent of radio brought with it the kind of democratic impulse that “turns all participants into listeners and authoritatively subjects them to the broadcast programs of exactly the same.”72 Industry advocates frequently point to format variety on the airwaves, such as rock, classical, hot adult contemporary, and so on as the quantifiable indicator of programming diversity. The number of formats provided by radio stations increased in all markets between 1996 and 2000. Adorno recognized the tendency in the music industry to proliferate categories: “The types of popular music are carefully differentiated in production.… This labeling technique, as regards type of music and band, is pseudo-individualization, but of a sociological kind outside the realm of strict musical technology. It provides trademarks of identification for differentiating between the actually undifferentiated.”73 As if to bear out Adorno’s analysis, a study by the Future of Music Coalition shows that the quantitative focus on formats alone hides from view the interconnections between formats: “The format variety is not equivalent to true diversity in programming, since formats with different names have similar playlists. For example, alternative, top 40, rock and hot adult contemporary are all likely to play songs by the band Creed, even though their formats are not the same. In fact, an analysis of data from charts in Radio and Records and Billboard’s Airplay Monitor revealed considerable playlist overlap — as much as 76 percent — between supposedly distinct formats. If the FCC or the National Association of Broadcasters are sincerely trying to measure programming ‘diversity,’ doing so on the basis of the number of formats in a given market is a flawed methodology.”74 While finely tuned to segment their audiences on their advertisers’ behalf, Clear Channel’s formats are in fact nearly indistinguishable: “AC” (Adult Contemporary) is contrasted with “Hot AC,” while “CHR” (Contemporary Hits Radio) is contrasted with “CHR Pop,” and “CHR Rhythmic.” When the historically mandated values of diversity and localism are distorted to reflect the formulaic equations of industry rationalization, they frequently manage to conceal precisely the opposite tendency: less broad-based musical diversity and less actual promotion of local artists. The rationalization of the debate through concept-metaphors like “formats,” “metrics,” and the like, becomes a case of what Horkheimer and Adorno call false clarity: “False clarity is only another name for myth; and myth has always been obscure and enlightening at one and the same time: always using devices of familiarity and straightforward dismissal to avoid the labor of conceptualization.”75

Ratings-based coverage has resulted in standardized, homogenized programming with diminishing playlists coming out of corporate headquarters, where they have been decided on the basis of profit revenues alone. When record executives promote new artists, for example, corporate interests explicitly overshadow aesthetic ones. Consider the criteria used by Jason Flom (a senior promoter at Warner Music Group) to promote a new singer, Cherie, as reported by John Seabrook: “Cherie’s music fits almost perfectly into the adult-contemporary format, radio’s largest; Flom thought that Cherie was tailor-made for New York’s WLTW 106.7 Lite-FM, the city’s most popular music radio station, which is owned by Clear Channel.… With luck … Cherie’s first single would be a hit, and would cross over from the light-FM stations to the Top Forty stations. At that point, Lava would release the second single, a ballad.”76 Thus executives readily admit the latent conformism of their aesthetic choices, no less than the (fraudulent) crossover potential of their favored genres.

Yet, the censorious dimensions of unfettered commercialism are routinely overlooked. In fact, there is a widespread belief in the West that censorship and restrictions on artistic expressions are properly pernicious only when they are imposed directly by the State. Edward Herman and McChesney point out that the “U.S. First Amendment protection of free speech is addressed solely to government threats to abridge that right.”77 It is as if today’s economies of power — corporations — lie beyond the scope of the First Amendment. But, from the perspective of independent musicians, the market imposes censorship every bit as insidious as that imposed by the State; and from the perspective of listeners, the market imposes limits on choice and quality as insidious as a cultural agenda imposed by the State. The market may seem to be a value-free and neutral measure of consumer’s tastes and interests, but this is not so. Just because consumers enjoy a particular song, does not mean their enjoyment is informed by a real choice. Horkheimer and Adorno cynically describe the mechanics of consumer choice thus: “The industry submits to the vote which it has itself inspired.”78 Transposing this thought to the field of advertising proper, just because a Hummer makes its drivers feel sexually attractive and sophisticated, does not mean that buying the car accurately reflects the consumer’s top choice for satisfying his natural need for sexual attractiveness and sophistication. Adorno describes the mechanism of consumption through the psychological categories of mimetic adaptation: “The culture industry piously claims to be guided by its customers and to supply them with what they ask for.… Its method is to anticipate the spectator’s imitation of itself, so making it appear as if the agreement already exists which it intends to create.”79 Cultural critics may be skeptical of Adorno’s description of the culture industry, but business executives are acutely attuned to it. In fact, the aggressive manufacture of consumer demand today exceeds the manufacture of apparent “agreement” (to which Adorno alludes) to the manufacture of consumers apparently dictating to industry. On marketing tactics for teenage girls, for example, Fortune magazine advises, “you have to pretend that they’re running things.… Pretend you still have to be discovered. Pretend the girls are in charge.”80 In this manipulative play of imagined choices, consumer demand is, at most, but one factor among many in production. As the March Hare in Alice in Wonderland explains: “You might just as well say that ‘I like what I get’ is the same thing as ‘I get what I like’.”

Thus, the media’s horizon of choice conforms less to any natural audience demand than it does to managerial imperatives and corporate politics. Horkheimer and Adorno’s claim that “there is the agreement — or at least the determination — of all executive authorities not to produce or sanction anything that in any way differs from their own rules, their own ideas about consumers, or above all themselves,” is strikingly pertinent today.81 The content of what is produced must be within the ideological range and political interest of its producers. Purely market-based media naturally tend toward political conservatism. Consider the role of advertising. Advertisers routinely complain about contentious content and politically charged news coverage. Proctor and Gamble, for example, explicitly prohibits using its advertisements alongside programming “which could in any way further the concept of business as cold, ruthless, and lacking all sentiment or spiritual motivation.”82 Likewise, S.C. Johnston & Co., for example, specify that its advertisements “should not be opposite extremely controversial features or material antithetical to the nature/copy of the advertised product,” just as De Beers stipulates that its advertisements should not appear alongside “hard news or anti-love/romance themed editorial.”83 When the media is beholden to the demands of advertising, it will favor programming that adds value to the advertised products. Basketball coverage sells sports drinks and running shoes, soap operas sell clothing and bathroom products. Horkheimer and Adorno recognized the dangers of advertising-based programming: “Today, when the free market is coming to an end, those who control the system are entrenching themselves in it. It strengthens the bond between the consumers and the big combines. Only those who can pay the exorbitant rates charged by the advertising agencies, chief of which are the radio networks themselves; that is, only those who are already in a position to do so, or are co-opted by the decision of the banks and industrial capital, can enter the pseudo-market as sellers.”84

This logic applies equally to corporate-controlled music. As a Clear Channel executive, who runs twenty-six stations in the Washington, D.C. area said in the Washington Post: “Every issue we discuss, every decision we make comes down to a simple test: Will it increase ratings and revenues? If it doesn’t let’s move on.”85 Lowry Mays, Clear Channel’s CEO sums up this point of view: “We’re not in the business of providing news and information. We’re not in the business of providing well-researched music. We’re simply in the business of selling our customers products.”86 Just as tabloid news and entertainment is given preference over informed political discussion and debate, cost-effective and undemanding music is given preference over music designed to challenge. Music broadcast under the directives of cost and benefit calculations, seeking to optimize sales and the delivery of affluent audiences to advertisers, is not likely to include certain kinds of musical experiences and expressions. On a fairly obvious level, lengthy pieces, which encourage sustained engagement, for example, are unlikely to make the cut. Horkheimer and Adorno make the point in the context of the boredom/pleasure nexus: “No independent thinking must be expected from the audience: the product prescribes every reaction.… Any logical connection calling for mental effort is painstakingly avoided.”87 Likewise, musical programming encouraging listeners to make their own music outside of the commercial structures will be ignored. Musical literacy, in other words, does not add to commercial media income, and hence will be discouraged under competitive market circumstances.

Negus points out, for example, that experimental or avant-garde music, along with jazz and classical music, are generally considered a bad investment, even if they are sometimes retained for the purposes of prestige and morale.88 The Washington Post reports, “in the last few years, Washington listeners have lost far more music choices than they have gained … jazz (WDCU was sold to C-SPAN, which uses the frequency as a prototype of a satellite-delivered national audio service); bluegrass (WAMU dropped much of its local music programming to serve up more news and talk produced for a national audience); and classical (WETA dropped some daily music offerings to simulcast news programs already heard on WAMU).”89 The New York Times reports that the days when unusual music or unknown bands might gain airplay through their own initiatives are over.

This sort of thing was still possible in the early 1980s, when an unclassifiable band out of Athens, Georgia, called R.E.M. became hugely popular while barnstorming the country in a truck. R.E.M. forced itself onto the air without conceding its weirdness and became one of the most influential bands of the late 20th century. Radio stations where unknown bands might once have come knocking at the door no longer even have doors. They have become drone stations, where a once multifarious body of music has been pared down and segmented in bland formats, overlaid with commercials. As record companies scramble to replicate the music that gets airplay, pop music is turning in on itself and flattening out.90

The illusion of multiple formats notwithstanding, therefore, the consolidated music industry is excluding swaths of possible music.

Also excluded are materials that the audience might choose to hear, but which might stir controversy objectionable to advertisers. When Nathalie Maines, lead singer of the Dixie Chicks announced at a concert in London in April 2003 that she was ashamed President George W. Bush came from her home state of Texas, KRMD, part of Cumulus Media, organized a CD-smashing rally in Louisiana. The radio chain then blacklisted the Dixie Chicks from its playlists.91 Two DJs at KKCS in Colorado were suspended for playing a Dixie Chicks song.92 Prominent Clear Channel stations joined Cumulus Media in banning the Dixie Chicks from their playlists in April 2003; and simultaneously sponsored a series of prowar rallies in various cities. (Following threats to themselves and their families, the band eventually made a humiliating public apology.) Clear Channel’s intimate ties to the current Bush administration — CEO Lowry Mays is a personal friend of former president Bush, for example, and Vice Chair Tom Hicks is a member of the G.W. Bush Pioneer Club for elite and generous donors — exacerbate the inherent conservatism of the radio giant. Through veiled threats and invective directed at dissenting voices, Clear Channel promotes a conservative ideology and bullies its artists into acquiescence. Relatedly, the “catalogue value” of certain forms of rap music — with an antiassimilationist, aggressive postcivil rights stance — is generally considered short in comparison with conventional songs.93 The more adventurous and critical rap is thus steadily marginalized commercially as the genre gains market share (with marketable stereotypes like Nelly, Jay-Z, and Ja Rule). In other words, if music becomes too experimental or socially critical, or its appeal falls too far outside of a narrow moneyed demographic, then its commercial production becomes precarious and unstable. Even rap music is dependent on this demographic: sales figures indicate that 75 percent of rap albums are purchased by white male teenagers.94

Commercially driven controls on music making obviate experimentation and risk taking in the service of a simplified world of music. The economically calculated inclination toward stability, predictability, and containment results in stabilized, predictable, and contained musical commodities. It is true that musical production is a dynamic process, which often crosses aesthetic and demographic borders. It is also true that a degree of genuine novelty and stimulation are required to sell any musical product. In fact, music companies are vigilant about avoiding the inertia of an overly narrow focus on predictable hits. The demand for permanent renewal of musical styles feeds the commercial machine. As a result, edgy street-styles (like the hip hop of Run DMC), trendy psychological attitudes (like the ironic postmodern detachment of Beck), progressive causes (like Moby’s endorsement of the basic rights of animals and homosexuals), and even antiestablishment political stances (like the Chomsky-inspired rage of Rage Against the Machine) have become lucrative investments in their own right. They have also become lucrative sites for mass-produced products. Moby, who licensed every track from his 1999 album Play for advertising use, advertised Levi jeans on painted walls in New York City; Rage Against the Machine publicly endorsed Wu-Wear, a clothing company and accessory company established by the Wu-Tang Clan; and, most famously, Run DMC’s 1980s hit song “My Adidas” practically launched a new line of Adidas shoes — “designed to be worn without laces.”95 The branding of independence and dissent has even become the subject of recent rock music. In the song “That’s How Grateful We Are,” Chumbawamba ironically proclaims, “They sell 501s and they think it’s funny. Turning rebellion into money.”96 This seeming proliferation of adversarial perspectives surely suggests a healthy “free market of ideas,” but closer inspection of the evidence suggests otherwise.

First, their popularity notwithstanding, the progressive artists outlined above are relatively marginal in the world of commercial music. Chumbawamba or Rage Against the Machine, say, are not marketed and distributed with nearly the same financial resources as, say, Britney Spears or Creed (now Alter Bridge). Second, record companies and radio stations tend to seek out edgy styles and ideas to systematize production on a mass scale; that is, to manufacture cost-effective standardized versions of those styles for mass consumption. The trendy buzz on the street thus serves to endow bland and conformist music with an aura of authenticity, a new sound, a fresh set of values, an attitude. Once again, cultural critics may be uncomfortable reducing the politics of consumption to the acquiescent dimensions of a herdlike mass, yet this is precisely the way company executives think about their consumer base. Marcus Morton, Vice President of Rap Promotion for EMI describes the process: “You have to have the DJs and the people that are the trend-setters. They kind of herd the sheep around.… And everybody else — y’know, if you look at the people that programme the cross-over stations, nine out of ten of them think that they are the hippest thing on the planet, but in reality they are not. They listen to somebody else.”97 Using well-developed mechanisms of persuasion, the music industry thus concocts a demand for ever-renewed pseudoindividualized sensation. Adorno explains:

[The industry] must arouse attention by means of ever new products, but this attention spells their doom. If no attention is given to a song, it cannot be sold; if attention is paid to it, there is always the possibility that people will no longer accept it, because they know it too well. This partly accounts for the constantly renewed effort to sweep the market with new products, to hound them to their graves; then to repeat the infanticidal manoeuvre again and again.98

The culture industry thus aims to optimize an ever-increasing cycle of commodity production and destruction. While changes in fashion are sometimes grounded in genuine sociocultural needs, most of the music produced in the ensuing style cannot answer to these needs. Necessarily, such music is drained of musical or social values that may transcend the contingencies of that style. So, musical expressions that encourage the discipline of imaginative concentration, for example, will not be marketed or promoted. The more deeply satisfying and rewarding to listeners such music turns out to be, the less it is in the interest of the commercial industry to produce and promote it. With its exclusive focus on maximizing turnover through rapid-fire stylistic shifting, the industry favors music that will perish soon after it has been purchased. This is the mechanism that Horkheimer and Adorno call the “built-in demand to be discarded after a short while,” or, speaking more generally, the mechanism that Slavoj Zizek calls the “capitalist logic of waste and planned obsolescence.”99 Paradoxically, therefore, far from turning out musical novelty or transforming musical paradigms, the industry’s changing styles offer pseudonovelty — musical sensations contained in the rigid and uniform schemata of formatted music.

Obvious examples of musical bands conceived as prefabricated brands include the Backstreet Boys, N’ Sync, the Spice Girls, All Saints, and so on. Of course, formulaic music is not itself a new development, as the example of Tin Pan Alley songs should suffice to attest. Nor is current music newly commodified. Instead, the current moment, while rooted in the past, elaborates new forms of commodification; one that permeates the sound of quality musical acts with equal force. The new formulaic mediocrity on centralized mainstream radio is characterized by musical conformism increasingly integrated with conservative values. The Christian rock music circuit, for example, has flourished in recent years, especially in Texas. Columbia Records signed the Christian grunge band Switchfoot in June 2003; Chevelle was on Ozzfest 2003 (the summer hard-rock tour led by right-wing rocker Ozzy Osbourne); Evanescence’s album “Fallen” reached No.3 on the Billboard charts in early 2003; and Creed’s songs repeatedly appear in the Top 40 charts.100 Likewise, music that endorses conservative government policies gained considerable airplay in the years 2001 to 2004. Take the sound Clear Channel radio stations promoted during the Bush administration’s various antiterror campaigns following September 11, 2001. Radio playlists increasingly featured music conforming to the conservative agenda of the Bush administration, such as Darryl Worley’s “Have You Forgotten,” and “Courtesy of the Red, White and Blue (The Angry American)” by Toby Keith, both of which explicitly promote administration-friendly politics.101 This conservative promotional effort encourages musicians to conform to the demands of ruling party politics. In the words of Bruce Springsteen, “The pressure coming from government to enforce conformity of thought concerning the war and politics goes against everything that this country is about — namely, freedom.”102

Mainstream radio playlists increasingly feature homogenized, sanitized songs that sound more like they were created by carefully crafted public opinion polls than by an artist. The website http://hitsongscience.com even offers a computer-based program that gauges a potential hit according to certain technical features. Recall the analyses of data from the charts conducted by the Future of Music Coalition. These indicate considerable playlist overlap between seemingly discrete formats. This study singled out the band Creed as an example of a band featured on many formats including rock, hot adult contemporary, top 40, alternative, and so on. Yet Creed’s musical and political sympathies reflect a fairly narrow conservative agenda: a certain brand of organized religion, mainstream family values, and patriotism. The acknowledgments on their Human Clay album, for example, begin by thanking God and their families; the web page for the “With Arms Wide Open Foundation” sports an American flag blowing as if in a breeze, with the insignia “Our thoughts and prayers are with our American troops in Iraq….”103 This is not an attempt to attribute Creed’s conservatism to institutional forces alone. For example, the authentic Christian origins of the band are well-known. Nor is this an attempt to denigrate the aesthetic power of Creed’s music. On the contrary, few would deny the high quality of their sound. Rather, this is an attempt to demonstrate what kind of musical beauty is given pride of place in the consolidated media structures and to mark its aesthetic limits.

Adorno opens his essay, “The Radio Symphony: An Experiment in Theory,” with an aim to investigate “what radio transmission does musically to a musical structure.”104 What are the structural features of Creed’s most popular songs? Musically speaking, Creed’s conservatism is neatly integrated with corporate values. Their massive 2000/2001 hit “With Arms Wide Open” (from the album Human Clay), for example, conforms precisely with the basic slow ballad pattern articulated by David McDonagh of PolyGram as a recipe for success: two verse/chorus segments, a short guitar solo followed by a final verse, with more vocal intensity and less melodic contour, and a final chorus which dissipates the tension by withdrawing the musical instruments and focusing on the open-ended simplicity of the words of the title. The lyrics of the song also conform to the demands of record executives. Paul Moessel (producer at Warner Music Group) explains: “If you are writing an artistic song, you write from inside yourself. You say, oh, I don’t know, ‘My dog died today,’ or something like that. But if it’s a commercial song you look for uplifting things.”105 Thus, to a succession of regular chord changes in “With Arms Wide Open,” the narrator (unambiguously male) sings of his tears and prayers at hearing the news that his wife is to give birth to his child (again, unambiguously male): “Well, I just heard the news today/It seems my life is going to change/I closed my eyes, begin to pray/Then tears of joy stream down my face,” and so on. The predigested structure of the song seamlessly undergirds the predigested representation of human relations, marked by idealized personalities in an idealized situation, with which the listener phantasmatically identifies. What rhythmic interest the song provides (in the form of a pronounced offbeat in the snare drum — mostly anticipatory, sometimes delayed — recurring around the second beat of each line) functions as the pseudodiffer-entiation that merely confirms the basic time. Conformist throughout, the song paints a procreative Christian scene, a story of a man and a woman, whose unsullied wish emerges in the predictable folds of the song’s ballad structure. This happy embrace of form and content reassures the listener and affords him a temporary glimpse of an emotional-erotic-religious idyll. If we weep, however, it is probably because these ideal qualities are mostly missing in real life. Adorno likens this “emotional type” of musical response to the psychological operation of wish-fulfillment: When audiences of sentimental music “become aware of the overwhelming possibility of happiness, they dare to confess to themselves what the whole order of contemporary life ordinarily forbids them to admit, namely that they actually have no part in happiness. What is supposed to be wish-fulfillment is only the scant liberation that occurs with the realization that at last one need not deny oneself the happiness of knowing that one is unhappy and that one could be happy.”106 For Adorno, the cathartic release afforded by music of this emotional type does not genuinely discharge the social ill it summons. Neither does it relate dialectically to praxis, by, say, demanding reconciliation between the false substitution and reality. Instead, by frustrating the desires it stimulates, impeding their real-world satisfaction, the music’s promise is deferred, making way for the next commodity. Such music, therefore, effectively reconciles the listener to his social dependence. Its erotic–emotional satisfaction is illusory, escapist. As if to drive home the experience of missed fulfillment of happiness deferred, the next song on Creed’s album, “Higher,” passionately narrates an earnest longing for a Christian afterlife.

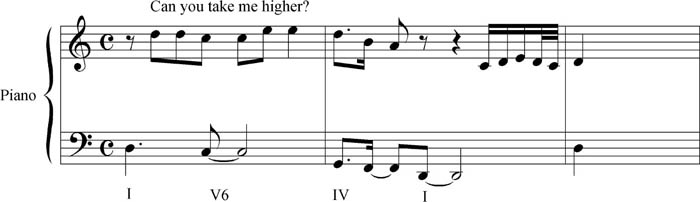

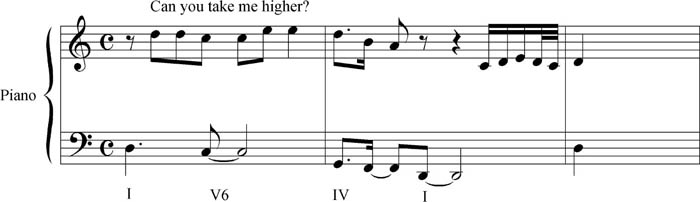

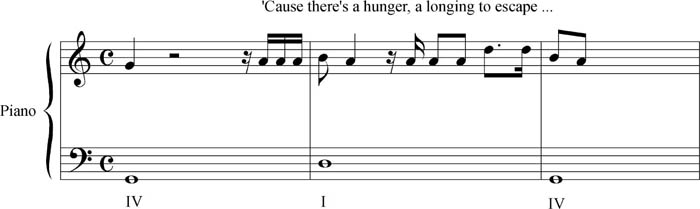

Under Adorno’s model of “pseudoindividualization,” “Higher” is memorable precisely in terms of features isolated by industry executives as crowd pleasing: a formulaically structured rock ballad, whose verse/chorus pattern is prominently elaborated by some attention-grabbing individual quality, in this case, a catchy electric guitar riff. In sync with the subject of its lyrics, one experiences the uncanny comfort, even on first hearing, of having heard it all before. The standardized banality of the song is offset by a particularly juicy moment (on the last beat of mm. 26 and 30): the highly distinctive melodic turn around the leading note in the chorus, which bridges the question “Can you take me higher?” (supported by a muscular, albeit hyperformulaic, descent to the tonic), and a description of the idyllic scene the narrator has in mind: “to the place where blind men see”/“to the place with golden streets.” To highlight this arousing riff, the studio mix has pushed the output levels of the drums and surrounding sonorities momentarily into the background (see Figure 8.1).

Fig. 8.1 Creed, “Higher” (from Human Clay), mm. 25–26.