Samuel Colman, Jr., Ships Unloading, New York (detail), 1868.

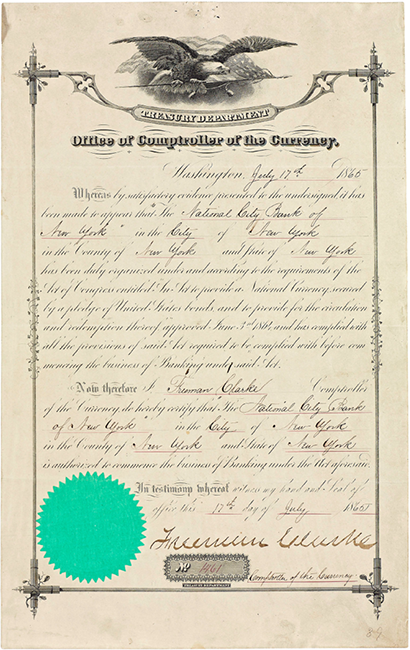

Charter certifying the City Bank as a National Bank (detail), July 17, 1865.

“EZRA COOPER, SAVANNAH. WHO’S HE?”

“First-rate man. Owns a plantation with two hundred slaves. Customer of ten years' standing.” With these words, the banker and writer James Sloan Gibbons captured the conversation between two New York City bank directors in 1858 as they considered whether to make a loan to a Georgia planter. As Gibbons and many of his readers knew, the business of New York and the business of slavery were intertwined. Cotton was king in the merchants’ counting houses of Lower Manhattan, just as surely as on Southern plantations and on the docks of Savannah, Mobile, and New Orleans. By 1822, when cotton represented about one-third of all American exports, “white gold” was New York City’s most profitable domestic export, making up 40 percent of the value of the cargoes shipped from East River piers. But New York’s interest extended more broadly into the financing of the South’s cotton crop. As conflict loomed between North and South in the late 1850s, New York’s banks were a critical force both above and below the Mason-Dixon Line.1

New York bankers would experience the Civil War as an upheaval that transformed their industry and indeed, the very nature of the nation’s financial and monetary systems. Over the course of a mere four years, the bloodiest war in American history cost the U.S. government an estimated $5.2 billion and changed basic assumptions about banks, their role in the national economy, and their relations with Washington. A new wartime national currency replaced the flood of bank notes issued by a multitude of state-chartered banks, a new National Banking System gave the federal government unprecedented influence in the country’s financial affairs, and the long-cherished idea that paper money had to rest on a base of gold and silver was overturned. These changes often alarmed and angered New York bankers. Yet these men ultimately played crucial roles in shaping and accepting the innovations that the war fostered, for New York’s banks were among the most critical weapons in President Lincoln’s arsenal for crushing the Southern rebellion. Despite their disagreements among themselves and their resistance to new policies, the city’s bankers emerged from the war more powerful and important than ever before. But the changes came unpredictably. When Confederate gunners commenced firing on Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor on April 12, 1861, no one on Wall Street or anywhere else could foresee how revolutionary for banking the conflict would become.

A Divided City

Prior to the war, some observers considered New York City the true capital of the South. As Gibbons explained in his book The Banks of New-York (1859), the entire Southern economy ran on loans, many of which originated in or were channeled through New York. Before cotton (and other Southern products like sugar and tobacco) was even planted, the planters needed credit so they could afford to grow and harvest the crop, feed and clothe their enslaved labor force, and buy new land and slaves. New York banks loaned capital for these purposes by discounting the promissory notes of planters, and by the 1820s they were also extending credit to Southern dealers, known as factors, who acquired the cotton from the planters. Manhattan banks also served merchants in coastal ports (including New York) who took delivery from the factors and shipped the cotton to New England, the French port of Le Havre, and most importantly, Liverpool in England, where English dealers sold it to Manchester factory owners whose workers turned it into cloth. Much of that cloth came back to New York for sale in the wholesale dry goods stores of Pearl Street merchants.

From the Wall Street insurers who underwrote policies on plantations to the seamen who manned transatlantic packet ships, dependence on the South pervaded almost every corner of the city’s economy. Not surprisingly, pro-Southern and proslavery feeling was rife in many of the city’s counting houses and banks, as well as in the Democratic Party. The New York-based Hunt’s Merchants’ Magazine unabashedly proclaimed in 1855 that “the whole Commerce of the world turns upon the product of slave labor.” The dependence was mutual. New York journalist Thomas Kettell noted in 1860 that the South “does little of her own transportation, banking, insurance, brokering, but pays liberally on these accounts to the Northern capital employed in those occupations.”2

Ladies’ night cap, ca. 1840. Embroidered muslin.

Museum of the City of New York, 34.225.2a

Ladies’ and children’s caps, worn both indoors and out under bonnets, were among the many garments produced from domestically grown cotton. Their presence in 19th-century New York confirmed the economic interest that tied the city’s merchants and bankers to the cotton economy of the slave South.

Yet, as war neared, the officers of the city’s 55 commercial banks, 18 savings banks, and numerous private banking houses were a divided community, split like other New Yorkers in their views on slavery despite their ties to the Southern economy. No one proved this more fully than James Sloan Gibbons himself. In addition to being a banker, Gibbons was a Quaker abolitionist who despised slavery. His townhouse on West 29th Street, a “station” for slaves fleeing the South on the Underground Railroad, would soon be on the front line of New York’s own war over secession and slavery.

After the Fort Sumter attack, New York bankers jumped to the ready. At a mass patriotic rally attended by 100,000 New Yorkers in Union Square on April 20, the City Bank’s Moses Taylor mounted a podium to exhort the crowds to defend the Union. A newly formed Union Defense Committee, organized by “solid men of Wall Street,” including Taylor and others, used government funds forwarded by Lincoln to arm volunteer regiments. “There can be no neutrality now,” asserted Pelatiah Perit, president of the Seamen’s Bank for Savings. “We are either for the country or for its enemies.”3

Advertisement, Robt. Logan & Co., ca. 1860.

Collection of the New-York Historical Society

As this advertisement suggests, commodities made of Southern cotton were a daily feature of New York life.

Such statements differed markedly from the sentiments expressed by many bankers before Fort Sumter. Reliant as they were on Southern business, merchants and financiers had supported compromises to forestall the secession of Southern states and the coming of war. (So had the city’s heavily Democratic electorate, who overwhelmingly voted against the Republican Lincoln in 1860.) The loss of Southern trade, they realized, jeopardized the city’s economy. Some Democratic bankers, including August Belmont and the Bank of the Republic’s G. B. Lamar, a native Georgian, followed the lead of Mayor Fernando Wood, who suggested in early 1861 that New York too might secede from the Union and become a free port welcoming Confederate trade. Confederate eagerness to have Southern ports actively compete with New York, however, along with the need for patriotic unity as war neared, quashed such ideas. Belmont decided “to leave to my children instead of the gilded prospects of New York merchant princes, the more enviable title of American citizens.” Lamar, on the other hand, defected to the South, where he became an advisor to Confederate President Jefferson Davis.4

Business imperatives now also justified Lincoln’s war. Swift Union victory would reassert New York’s dominant position in Southern trade, as well as hopefully recover some $160 million in commercial debt to New Yorkers and other Northerners, which Confederate states and debtors had immediately repudiated. (Annoyed by an unpaid Northern merchant, a Southern customer wrote back, “I cannot return the goods, as you demand, for they are already sold, and the money invested in muskets to shoot you Yankees.”) A short war, moreover, would reunify the Union without ending slavery in the Southern states, allowing merchants and bankers to resume their old cotton trade as if it had never been disrupted.5

“Gentlemen, the War Must Go On”

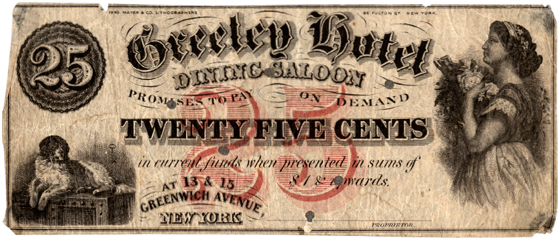

Meanwhile, President Lincoln and his Secretary of the Treasury, Ohioan Salmon P. Chase, faced the daunting task of finding the money they needed to fight the war. From the start, the aid of New York’s banks was clearly vital for crushing the Southern rebellion. In July 1861, Chase persuaded Congress to allow him to borrow $250 million from the American people to pay for the war. Never before had the government proposed to borrow so much. Chase believed that a massive issue of government bonds, marketed throughout the North by leading banks, would be needed. In pursuit of this plan, the U.S. Treasury now began to issue “demand notes,” as well as bonds payable in 20 years and short-term treasury notes that would yield interest of 7.3 percent. The government would pay the demand notes directly to its employees, to soldiers, and to merchants selling supplies to the Union Army and Navy. Northerners would be able to redeem these notes in gold or silver coins at the federal subtreasuries in the major cities. (New York’s was located at 32 Wall Street.) Issued in 5-, 10-, and 20-dollar denominations (with portraits of Alexander Hamilton, President Lincoln, and a figure of Liberty staring out from them), these demand notes would circulate as money, a novel federal currency in a nation still flooded with $200 million in several thousand different types of paper money issued by 1,600 state-chartered banks.

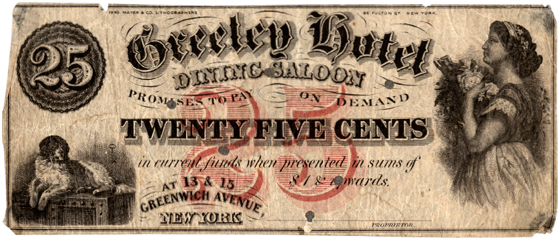

Greeley Hotel Dining Saloon, Twenty-Five Cents Note, ca. 1862.

Museum of the City of New York, 29.100.3276

Before and during the war, New York hotels, restaurants, and saloons that did not have enough coins or bank notes to make change sometimes issued their own money in small denominations (also called shinplasters). Although such notes might pass from hand to hand, ordinarily they would have to be spent or redeemed in the establishment that issued them.

The Treasury relied on the nation’s major banks to sell the war bonds and interest-bearing treasury notes to patriotic purchasers. The disastrous Union defeat at Bull Run on July 21 lent special urgency to the need to support Washington’s war effort. In August, Chase traveled to New York to meet with bankers from Wall Street, Philadelphia’s Chestnut Street, and Boston’s State Street, the Union’s three leading financial centers. Wall Street had become the nation’s capital of “loan contracting,” in which private bankers and commercial banks bought large issues of bonds and resold them to domestic and foreign lenders, who might be individuals, trust companies, or other banks. Unlike the War of 1812, when a small group of New York and Philadelphia businessmen had sold the government’s war bonds, and the Mexican War, when Washington and London financiers had dominated bond sales, the national emergency required the mass mobilization of the banking capital of the Northeast. In meetings at the Fifth Avenue home of Assistant Secretary of the Treasury John Cisco and at Wall Street’s two richest banks, the Bank of Commerce and the American Exchange Bank, Chase convinced the assembled New York, Philadelphia, and Boston bankers that they must buy and then sell to the public $150 million in bonds from the federal government in order to sustain the Union in its moment of greatest need. As befitted New York’s dominant role among the three cities, its banks agreed to raise $35 million of the first $50 million installment of the loan.

Cotton Is King

New York’s Role in the Atlantic Cotton Trade

In the years before the Civil War, New York banks helped to keep the nation’s vastly profitable cotton trade network running by facilitating loans that frequently spanned the Atlantic Ocean. An exporting merchant on New York’s South Street, for example, often borrowed from the Liverpool merchant to whom he consigned his bales of cotton. To do so, the New York merchant wrote and endorsed a document called a bill of exchange, committing the Liverpool merchant to pay $10,000 in, say, 60 days to whomever presented the bill for payment at that time. The shipped cotton was the collateral against this debt. Next, the New Yorker took the bill to his Wall Street bank. In exchange for handing it over and letting the bank deduct a “discount” or up-front interest fee of 7 percent per annum ($116.66 for 60 days), the merchant walked out of the bank with $9,883.34 in cash or deposit credit, money he could now use in his business or to pay his own expenses.

Meanwhile, the bank sent the bill via ship to its agent residing in Liverpool. At the expiration of 60 days, the agent would present the bill to the English cotton importer, who paid him the equivalent of $10,000 in English pounds. The English importer could do this, having already sold the cotton to a Manchester manufacturer whose factory workers would turn the bales into cotton cloth for sale. The New York bank gained either a direct payment or credit in a Liverpool or London bank for $10,000, having paid out only $9,883.34 on Wall Street and thus earning the $116.66. In this way, New York banks profited while facilitating the flow of credit from Britain to America, and of cotton from America to Britain. By discounting bills of exchange, they also put cash in the hands of American dealers who needed liquidity to stay in business. Farmers, shopkeepers, merchants, and bankers also used such bills in the export of western crops and the import of foreign goods, but it was arguably in the cotton trade that the bills were most useful.

Manhattan bankers earned other revenues directly and indirectly from slave-grown crops. The private banking house of Brown Brothers and Company, for instance, shipped the cotton of Southern merchants to Liverpool, for a commission. But the Browns also did a lucrative business in foreign currency exchange, charging a .5 percent fee for converting English pounds to American dollars in the fall and winter when New York cotton, tobacco, and wheat exporters were paid by their English customers. They also traded dollars for pounds in the spring and summer when New York importers had to pay for English goods (many of which were sold to Southerners). Meanwhile, Wall Street commercial banks accumulated the reserve balances that Southern and western banks deposited in their bank vaults, which New York bankers lent “on call” to brokers who traded in the city’s stock and bond markets. In these ways, a Southern agricultural system based on the labor of 4 million enslaved African Americans pervaded New York’s finances and indeed, the entire nation’s economy.

—Steven H. Jaffe

Samuel Colman, Jr., Ships Unloading, New York, 1868. Oil on canvas mounted on board (41 × 29

× 29 in).

in).

Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, 1984.4

Artist Samuel Colman, Jr., depicted Southern cotton being unloaded on the East River waterfront prior to its storage in warehouses or transfer to ships bound for England or France.

“Gentlemen, the war must go on until the rebellion is put down, if we have to put out paper until it takes a thousand dollars to buy a breakfast.”

Salmon P. Chase

Although the bankers formed a consortium under Moses Taylor’s leadership and consented to Chase’s request, many did so unhappily. Chase, who had begun his political career in Ohio as a Jacksonian Democrat, insisted on following the “hard money” philosophy of the 1846 Independent Treasury Act, which required all payments to the federal government to be in specie (gold or silver). In enabling the government to fight the war, New York’s banks would have to pay for the federal bonds in specie, which would flow into the Treasury and then circulate freely when the government redeemed the demand notes it paid its suppliers, soldiers, and employees. But this process, many bankers warned, risked draining Wall Street’s specie reserves and leaving New York and the North vulnerable to precisely the kind of panic that had led to financial collapse in 1837 and 1857.

Instead, the banks wanted the Treasury to open bank deposit accounts at their establishments. As ordinary citizens bought the war bonds and treasury notes from the banks and the banks, in turn, deposited the proceeds in those Treasury accounts, the government could then write checks to pay suppliers and troops, all without exhausting bank specie reserves. But Chase was uncompromising. In one meeting, he threatened that unless the bankers bought the bonds and treasury notes with their gold and silver, the Treasury would unleash an irredeemable flood of securities and paper money in order to buy war supplies, severely inflating prices across the North: “Gentlemen, the war must go on until the rebellion is put down, if we have to put out paper until it takes a thousand dollars to buy a breakfast.”6

The New Yorkers, however, had predicted correctly: by late 1861, massive payments in gold to the Treasury for its securities were reducing the specie reserves of the banks. Moreover, the Treasury had trouble keeping the first demand notes in circulation. When they were paid to government workers and troops that fall, the New York Herald reported that laborers in New York’s harbor and Union soldiers in Virginia, not trusting that they were truly money, quickly redeemed them for coins at U.S. subtreasuries. Only coins, not demand notes, were legal tender, meaning that Northerners could refuse to accept demand notes in payment for a debt. When holders of the notes tried to deposit them or get them redeemed in New York’s banks, some bankers refused to accept them; James Gallatin of the National Bank, for example, allegedly ordered his tellers to “throw out” the demand notes (i.e., refuse to deposit them or exchange them for coins) when they were presented by customers. Meanwhile, instead of circulating as Chase had expected, gold and silver coins largely vanished: individuals hoarded them as a source of secure and appreciating value in a time of economic turbulence, and as the Union Army seemed unable to win the war. Facing an ongoing drain on specie by December 1861, banks in the city and across the North suspended specie redemption (stopped paying out any gold and silver for customers’ bank notes and checks). The banks would remain off the “specie standard” until 1879; only then did redemption of paper money for metal resume.7

Greenback, March 10, 1863.

Museum of American Finance, New York City

Greenbacks and National Banks

Recognizing that the Northern economy needed a more ample and liquid money supply in order to win the war, Chase resorted to a radical new plan in 1862 and 1863. Asserting that “it was the duty of the general government to furnish a national currency,” the secretary now pressed Congress to authorize the Treasury to issue a new paper currency “bearing a common impression.” These “greenbacks,” as they became known, would enter the economy as the government paid soldiers, sailors, and war contractors with them; as banks made loans and cashed checks for customers; and as citizens exchanged notes from state banks for the federal money. The greenbacks would not be redeemable in gold or silver, but they would be legal tender, to be accepted in payment for all private and public debts (except for customs duties and interest on the federal debt, which still needed to be paid in specie). Backed by the Treasury, and at least theoretically exchangeable for U.S. bonds five years after their issue, greenbacks would replace gold as the nation’s monetary standard. By war’s end, $450 million of them—adorned with portraits of Hamilton, Lincoln, and Chase himself—had been issued for circulation throughout the country.8

Advertisement for American Bank Note Company in English, French, and Spanish, 1869.

Collection of Mark D. Tomasko

Other countries relied on the expertise of the American Bank Note Company, and conversely, after 1877, the company depended on these countries to supplement their business of designing securities.

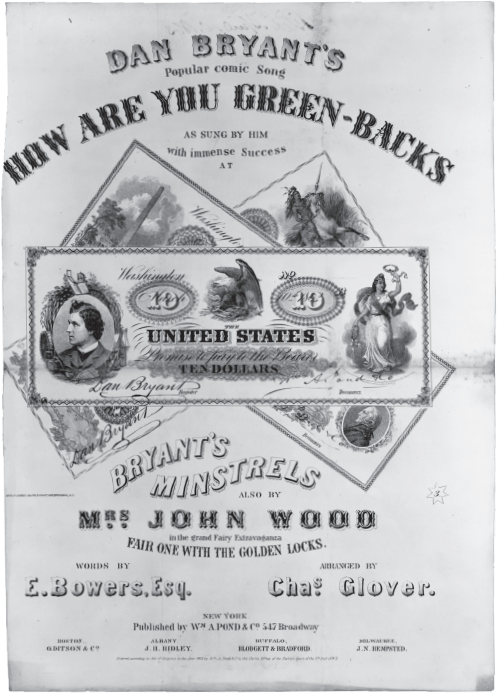

Dan Bryant’s Popular Comic Song—How are you Green-backs, ca. 1863. Lithograph.

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

As New Yorkers got used to the new greenbacks, entertainer Dan Bryant lampooned them in a song he performed on the New York stage. The song’s sheet music displays a mock 10-dollar greenback bill featuring Bryant’s portrait rather than President Lincoln’s.

Chase also resorted to one further innovation. He called for the creation of a network of National Banks across the Union, institutions that would help make the new currency a daily presence in the lives of Americans. These banks would augment the legal tender greenbacks by issuing another new set of government-authorized currency known as National Bank Notes. Chase and Lincoln intended that the new system would ultimately supersede and eliminate the existing hodge-podge of state-chartered banks with their confusing and easily counterfeited bank notes, replacing them with a truly uniform national banking and monetary system. Chase also insisted that the new federally incorporated National Banks buy U.S. war bonds, which would constitute security for the notes they issued. These bonds would be held in Washington by a new federal Comptroller of the Currency; if a holder of National Bank Notes insisted on “redeeming” them, he or she could do so at the issuing bank, but if that bank failed, the government could sell the bonds and pay the holder for the notes. Here, Chase was inspired by the Free Banking law pioneered by New York State in 1838, which similarly backed currency issues with bonds rather than specie. The secretary also killed two birds with one stone: by requiring National Banks to buy federal bonds, he made them put more money into Washington’s coffers to pay for the war.

Based on these ideas, three Legal Tender Acts (1862, 1863) and two National Banking Acts (1863, 1864) supported by Lincoln, Chase, and his eventual successors at the U.S. Treasury, William Fessenden and Hugh McCulloch, transformed the nation’s financial and monetary systems. By 1865, hundreds of millions of dollars in circulating greenbacks and National Bank Notes had become a truly national currency, a daily symbol of the growing political authority and financial power of the federal government. The National Bank Notes came adorned with patriotic images—Columbus discovering America, Washington crossing the Delaware, Franklin flying his kite—meant to transcend local and state loyalties and foster a national consciousness. But one locality, New York City, remained critical to this brave new world of federal innovation. Because Washington’s Bureau of Engraving and Printing existed only in rudimentary form, the U.S. Treasury resorted to the country’s most expert currency engravers—those of the American Bank Note, National Bank Note, and Continental Bank Note companies, all on or near Wall Street—to design and engrave the new money supply. These New York engravers would continue to design the nation’s currency until 1877, when a law declared that only the U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing could print government currency and securities.

A Federal Currency

Now that the wartime Congress had created a national currency, it also moved to eliminate the vast variety of state-authorized bank notes that had both served and bewildered Americans for some eight decades. A stringent 1865 federal tax on state bank-issued notes drove such notes out of circulation and persuaded most state banks to take federal charters and become National Banks. (Some 300 commercial banks across the country, including 12 in New York City, refused to do so, although they still lost the right to issue bank notes.) For many staunch Unionists in New York and throughout the North, the changes gave heft to a new muscular federal sovereignty and symbolized victory over the “states’ rights” philosophy that had spurred the Southern rebellion in the first place. Moreover, as one supporter asserted, the new system freed the government from the need to depend on “the irredeemable and depreciated notes of suspended banks” and the need to use them “as a medium in which to pay its debts to contractors and soldiers.” The power and creditworthiness of the federal government, not the ability to trade paper for coins, now gave America’s money its value.9

Like the earlier demand notes, the new currency took some getting used to. As they grew accustomed to the strange new notes, and as the Union’s ability to fight and probably win the war became surer, many Northerners welcomed money issued by a common source and hard to counterfeit. As the Herald asserted, Americans “hail with joy a currency standing on the good faith of the nation—a currency as secure as the nation itself.” Thus, in the midst of the Civil War, Washington initiated and Wall Street engravers designed a currency that automatically increased the federal presence in the daily lives of Americans, and created a truly national monetary system that we still have today.10

The government also acted to protect the new currency and its users. While the uniform appearance and limited variety of greenbacks made them hard to counterfeit, New York was the favored city of those who tried. By 1865, however, agents of a new federal department, the Secret Service, were busy raiding East Houston Street saloons to track down Jim Colbert, “Blacksmith Tom” Gurney, and other engravers and passers of fake greenbacks. (See Chapter Five, Sidebar: Pursuing the Counterfeiters.)

Tugs-of-War

Given their centrality in the nation’s economy and in the war effort, New York bankers played an outsized role in the behind-the-scenes tugs-of-war that shaped these revolutionary changes. Several important bankers realized that in the face of specie suspension, a legal tender paper currency was a wartime necessity, and they pressed Chase to create one. But others feared the inflationary impact of the greenbacks and opposed issuing them. Many New York financiers, moreover, fearing the loss of control over their own businesses, resisted the conversion to the National Banking System. The climax of this movement came in September 1863, when Augustus Silliman, influential president of the Merchants’ Bank and a founder of the New York Clearing House, called on the city’s banks not to cooperate with the federal government in implementing the new system.

In confronting Wall Street resistance, however, Chase also had important allies, and some tricks up his sleeve. New York bankers John Thompson (also editor of Thompson’s Bank Note and Commercial Reporter), George F. Baker, and John A. Stevens were his friends and advisors during the war. As an expert on counterfeiting, Thompson encouraged Chase to create a national currency and a national banking system, recognizing that such changes would eliminate counterfeits by curtailing the confusing variety of state-authorized bank notes. Thompson would go on to open the city’s First National Bank under the new system in 1863.

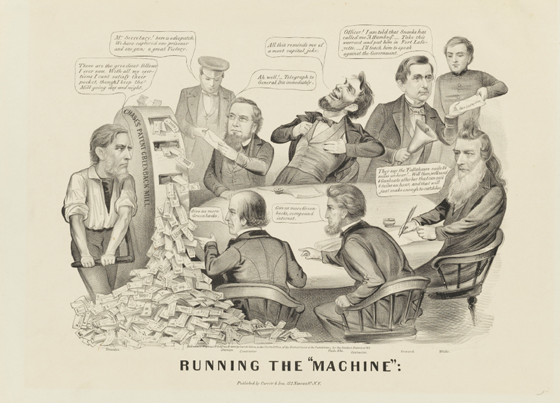

James B. Cameron, Running the “Machine,” 1864. Lithograph (13½ × 17⅞ in). Published by Currier & Ives.

Museum of the City of New York, Gift of Mrs. Harry T. (Natalie) Peters, 56.300.302

This cartoon, critical of the Lincoln administration’s wartime policies, shows the president and his cabinet, including interim Secretary of the Treasury William Fessenden (left), who cranks “Chase’s Patent Greenback Mill” to print more federal money to pay greedy war contractors.

Chase also relied on Jay Cooke, the brilliant Philadelphia banker who established New York City’s Fourth National Bank in 1864. During the war, Cooke successfully marketed one billion dollars’ worth of treasury war bonds to ordinary Northerners through newspaper publicity campaigns and networks of selling agents. In Manhattan, for example, Cooke’s agents opened “night offices” in Yorkville, Greenwich Village, the Lower East Side, and on West 49th Street and Canal Street to sell $50 and $100 war bonds to “Working Men and Women who haven’t time by Day.” Cooke’s leaflets exhorted them to “Make the U.S. Government Your Savings Bank” by buying interest-paying war bonds. A reporter noted machinists, shopkeepers, clerks, bartenders, cigar makers, “six store and working women,” ten “colored men,” and Irish, German, Portuguese, and Chinese immigrants among nocturnal bond buyers and observed that a week of nightly sales, mostly among New York’s “laboring classes,” had raised $96,000 for the Union. Now, with Chase’s approval, Cooke warned Manhattan’s reluctant bankers that if they did not join the national system, he would raise $50 million to open a national megabank in New York that would monopolize federal deposits and take business from the existing Wall Street institutions. The threat proved effective in quelling at least some of the opposition.11

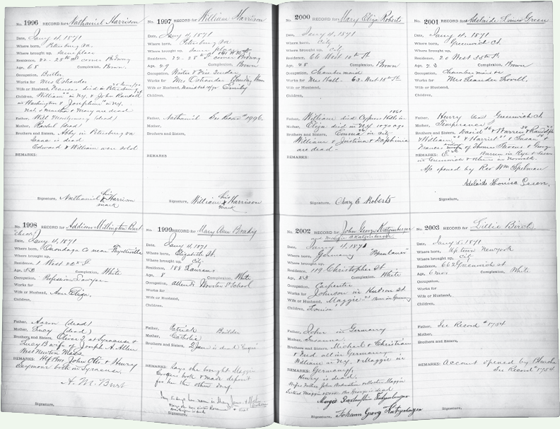

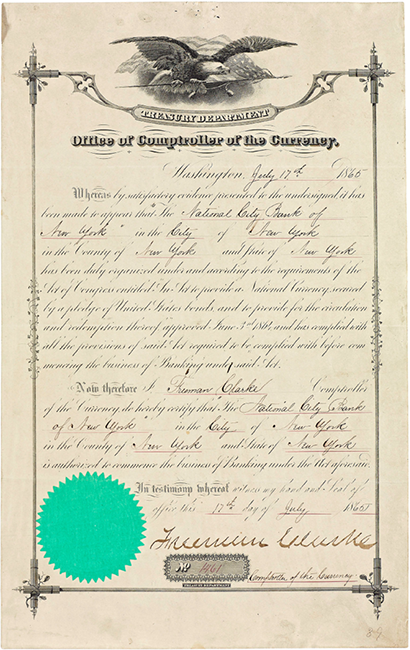

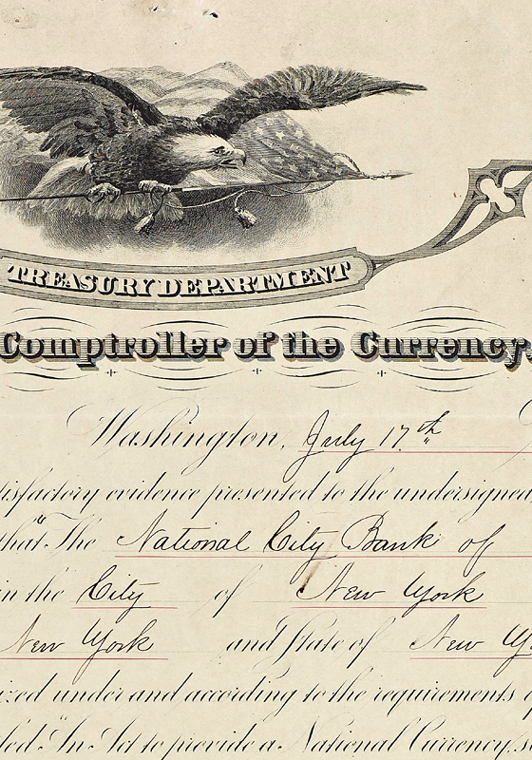

Charter certifying the City Bank as a National Bank, July 17, 1865.

Heritage Collection – Citi Center for Culture

By resisting change, New York bankers had gained crucial concessions from Washington and shaped the final form of the new national financial infrastructure.

In the end, though, resistant New Yorkers got much of what they wanted by prodding congressmen and Lincoln’s officials to rewrite the new banking laws. One feature of the 1863 Banking Act particularly alarmed the bankers: a measure requiring National Banks across the country to keep a significant reserve of specie and greenbacks on hand in their vaults to safeguard their own financial solvency. This mandate, the New Yorkers feared, would keep large sums of money in “country” banks, thus disrupting the annual flow of balances that these banks had been putting on deposit in New York banks since the 1820s. By 1860, in fact, 1,600 American banks and 900 private bankers kept $25 million on deposit with New York City banks and financial agents. These balances proved highly lucrative to the Manhattan banks, which loaned them out at interest to securities brokers and investors in the “call” market. Distant National Banks keeping large reserves, moreover, might even become rivals to New York in the country’s credit and investment markets.

Needing the support of New York banks in order to make the new system work, the Lincoln administration tried to meet the New Yorkers’ objections. Hugh McCulloch, then Comptroller of the Currency, persuaded Congress to revise the National Banking Act of 1864 to provide new incentives for balances to flow to Manhattan. Altered reserve rules now required National Banks across the country to place deposits in sister banks in 18 major cities, including New York, designated as the “Central Reserve City.” In turn, the “National Reserve Banks” in the 17 other cities also were to keep sizeable balances in New York City’s National Banks. Financial services and interest payments provided to these depositors made the arrangement attractive to bankers across the Union.

McCulloch’s revisions clinched the support of New York bankers. Though only three new National Banks had opened in Manhattan by autumn 1863, several important state-chartered commercial banks (including the nation’s richest, the Bank of Commerce) had converted to federal charters by war’s end in April 1865, bringing the city’s National Banks to 22, and to 58 a year later. The 1864 act thus encouraged the continued accumulation of bankers’ balances in Manhattan and gave such deposits federal legal sanction, confirming and augmenting Gotham’s financial supremacy. By resisting change, New York bankers had gained crucial concessions from Washington and shaped the final form of the new national financial infrastructure.

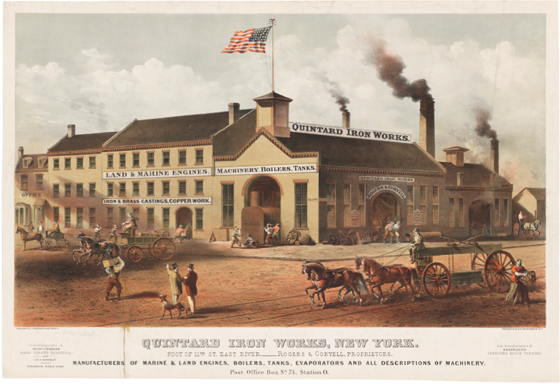

Quintard Iron Works, New York, ca. 1870. Lithograph (35⅝ × 23½ in). Published by L.R. Menger.

Museum of the City of New York, 60.122.8

War Boom

Meanwhile, the city’s economy was booming. Merchants made wartime fortunes shipping wheat to Europe and filling supply contracts for the Union Army and Navy; cotton would never again loom so large in New York’s warehouses and bank accounts. The war brought new players to prominence on Wall Street: the young J. P. Morgan dabbled in selling rifles to the army while also shipping railroad bonds to London, and a group of German Jewish immigrant brothers used profits from their uniform-making business to found the firm of J. & W. Seligman and Company to sell treasury bonds in Europe. These New Yorkers and others would go on to become the postwar nation’s most powerful investment bankers. The government’s need for guns, ships, uniforms, and other war materiel made Manhattan ever more clearly the North’s industrial center: by 1863, New York’s 6,000-odd factories almost exceeded the total output of the Confederacy’s manufacturers. Bank credit was a crucial resource for some of the largest factories: the Quintard Iron Works on East 9th Street, for example, mortgaged its buildings and land to the Bowery Savings Bank and Dry Dock Savings Bank.

While many merchants, contractors, and bankers profited extravagantly, there was another side to the urban war economy. While it never reached the extreme of the $1,000 breakfast threatened by Salmon P. Chase, wartime inflation—driven by rising prices and by the flood of greenbacks into circulation—eroded the incomes of working families. For those who could put some money aside from their wages, the city’s savings banks became a financial refuge; soldiers and working men and women opened thousands of new accounts at the Bank for Savings, the Bowery Savings Bank, and others. But by 1863, as the war dragged on and its casualty lists grew, many in New York’s large immigrant working class were reaching the breaking point.

The Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company

Creating an African American Bank

As the Civil War ended in 1865, a group of white abolitionists, philanthropists, and businessmen founded the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company to encourage “thrift, frugality, and foresight” among African Americans. Manhattan’s black population had been free since 1827 and had played a vigorous role in the city’s antislavery movement. But the community of about 10,000 faced persistent racism, discrimination, and poverty; in a racially segregated job market, most adults worked as laborers, servants, or small tradesmen. The brutal Draft Riots of July 1863 had taken the lives of at least 11 black New Yorkers and driven thousands to flee the city. But the riots also led Republican activists to turn their attention to the needs of African Americans and to found the new bank to help the city’s black population become financially self-reliant, much as earlier savings banks had served working-class whites.12

The first branch and initial headquarters was established in April 1865 on Cedar Street in Lower Manhattan, and after headquarters moved to Washington in 1868, the New York branch continued to act as a clearing house for the Southern branches. The bank was embraced by African American communities, and between 1865 and 1874 over $50 million was deposited by predominantly working-class individuals, churches, and community groups at 37 Freedman’s bank branches around the country.

Prior to the Civil War, organizations such as the New York African Society for Mutual Relief pooled community financial resources, and African American churches offered savings and credit services. Still, many African Americans were in dire need of banking services after emancipation—numerous initial deposits at the Freedman’s bank consisted of long-hoarded gold, silver, and bills, sometimes bundled in “paper, rags, and old stockings.” Thus, the bank both filled a pressing need and drew on a long history of African American community-based mutual aid and financial institutions.13

The surviving records of the New York branch offer tantalizing glimpses of African American life in postbellum New York. In 1871, for example, New Yorkers Nathaniel Harrison and his son William, former slaves from Virginia, opened bank accounts together. The Harrisons’ deposit record reveals a family rebuilding after years of slavery. Nathaniel’s wife and three of his six children were dead, his sister Abby remained in Virginia, and his brothers Edward and William had been sold before emancipation. Nonetheless, Nathaniel worked as a butler in New York City, his son was a waiter in a boardinghouse, and both saved their wages at the Freedman’s bank.

Other depositors at the New York branch included African American women such as Mary Eliza Roberts, a lifelong New Yorker, and Adelaide Green, who moved to the city from Greenwich, Connecticut. Both worked as chambermaids in Manhattan. Seeing their names side by side in the deposit record books, it is easy to imagine that the two young women opened their accounts together. (See next page.) The New York branch of the Freedman’s bank also served white New Yorkers, including Addison Burt, a well-off lawyer, and John Katzenberger, a 23-year-old carpenter born in Germany.

White New Yorkers may have used the Freedman’s bank out of the same charitable impulse that inspired its founding. More likely, they believed, like many African Americans, that the bank was secured by the federal government—a dangerous misconception that the bank encouraged through the use of patriotic imagery and by emphasizing its congressional charter. One advertisement referred to Abraham Lincoln: “He gave Emancipation, and then this Savings Bank.”14

Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company signature book, volume 35, 1871.

National Archives, Washington, D.C.

By 1870, the bank had drifted away from its philanthropic roots and come under the informal control of Jay Cooke, who used it to aid his brother Henry Cooke’s First National Bank of Washington by transferring bad assets from there to Freedman’s. In the aftermath of the Panic of 1873, the bank failed spectacularly. The panic laid bare a rash of mismanagement, ill-advised real estate speculation using bank funds, and fraud. In an effort to salvage the bank, the great African American abolitionist Frederick Douglass became its president and took control of the Washington headquarters in 1874, but it was too late. When it failed, the Freedman’s bank owed nearly $3 million to over 61,000 depositors. As the institution’s affairs were wound up, some depositors received three-fifths of their money. Many others received nothing.

The closure of the Freedman’s bank was financially devastating to many African American communities, and it inspired decades of mistrust in the American banking system. In The Souls of Black Folk, W.E.B. Du Bois would write that “all the hard-earned dollars of the freedmen disappeared … all the faith in saving went too, and much of the faith in men. … Not even 10 additional years of slavery could have done so much to throttle the thrift of the freedmen.” African American communities continued to find ways to save for the future, but many returned to mutual aid societies, churches and stockpiling currency over formal banking institutions.15

—Bernard J. Lillis

The explosion came in July 1863, when Congress authorized a national draft but exempted from the battlefield any man wealthy enough to pay a fee of $300 (the total annual income of many urban laborers). The outrage was explosive: in four days of rioting and bloodshed, thousands of working-class men and women—many of them Irish immigrants—rampaged through Manhattan. They targeted those they blamed for the war and its hardships: wealthy Republicans, abolitionists, and, most significantly, African Americans. The navy stationed a gunboat off the foot of Wall Street to keep rioters from breaking into the banks’ gold vaults, while marines and artillery guarded the U.S. Subtreasury at Wall and Nassau Streets. On July 14, a mob attacked the West 29th Street townhouse of James Sloan Gibbons, but failed to set it ablaze. Gibbons escaped unscathed, but his daughter Lucy watched from her aunt’s house two doors down as rioters “laden with spoils” looted her home. Police and Union troops put down the Draft Riots by July 17, but the bitterness spawned by the violence lingered. A month later the Republican lawyer George Templeton Strong, a trustee of the Bank for Savings, found it hard to contain his rage at working-class Irish immigrants as he served them at the bank: “On former occasions I have handed out pass books to Bridget and Catharine and their husbands and brothers with a sense of philanthropic enjoyment in aiding the poor to save money. … But I found myself today inclined to treat the Biddies and Mikes in a different spirit, and without a single spark of philanthropic sympathy.”16

After the July riots, elite New Yorkers feared the possibility of renewed working-class insurgency, but the war and its politics also pitted them against each other. Most Democratic bankers agreed with Republicans that the Southern rebellion had to be crushed, but many, like August Belmont, also continued to long for a resumption of their prewar trade networks. Belmont, chairman of the Democratic National Committee, spent thousands of dollars sponsoring pamphlets and newspaper articles that opposed Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation as a grave mistake that jeopardized chances for reconciliation between North and South. Belmont also became the promoter and campaign manager of ex-general George McClellan when he challenged Lincoln for the presidency in 1864. Other bankers, however, now supported emancipation as a war measure that would help kill the Confederacy. A young New Yorker, George F. Baker, soon to be a major force in the city’s First National Bank, was denouncing slavery as the “mainspring of rebellion” by late 1861, and even the Democrat Moses Taylor joined Republicans in backing Lincoln’s reelection. When Belmont-sponsored articles opposed emancipation as the “fanaticism of the hour,” the Loyal Publication Society, co-organized by Republican John A. Stevens, Jr., of the Bank of Commerce, condemned Democrats as “enemies of the government and the advocates of a disgraceful Peace.”17

While the political wrangling continued, some were beginning to recognize that the war was decisively turning the city and the North away from Southern agriculture toward the western grain exports, railroad investments, and industrial development that had already accelerated by the 1850s. The war “has released us from the bondage to cotton, which for generations has hung over us like a spell,” boasted the New York-based American Railroad Journal in October 1861.18

August Belmont, ca. 1844.

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

“Licking up the Cream of Commerce”

On April 3, 1865, Wall Street filled with thousands of exhilarated New Yorkers as news arrived of the Union Army’s triumphant entry into Richmond, the Confederate capital. “Never before did I hear cheering that came straight from the heart,” George Templeton Strong recorded. Although the assassination of President Lincoln 11 days later muted the victory celebrations and ongoing friction over politics, class divisions, and race continued to divide its inhabitants, New York emerged from the Civil War with much to celebrate. By 1870, as deposit balances from across the country flowed to the banks of the Central Reserve City, the policies of the National Banking System had consolidated New York’s dominant financial role. In that year, Manhattan banks controlled $432 million, or 24 percent of the nation’s total banking assets. The stock and bond markets boomed as brokers, speculators, and investors borrowed “call loans” from the Wall Street banks or used fortunes made in war contracting to buy and sell new railroad, municipal, and industrial securities.19

New York’s banks and bankers had been crucial players in the Civil War. Their funds had enabled the Union to keep fighting. Despite their own reservations, the city’s bankers had also helped create a new national banking and monetary system. Provided for the first time with a uniform currency backed by the federal government, Americans would no longer fight over the state-authorized, bank-issued paper monies that now vanished from circulation, or over Jacksonian policies for keeping government and banks totally separate. The war had transformed the federal government from a shadowy presence, encountered by most citizens only at the post office, into a national force that drafted soldiers, imposed income and property taxes, and issued money. At the same time, that government had expanded and consolidated the power of New York and its banks in an increasingly industrialized economy in which slavery was dead and cotton less important. The Central Reserve City of the government-sponsored banking system relinquished the kingdom of cotton for a new empire of railroads, factories, and steel. A remark by the Bostonian Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., seemed ever more accurate: New York was becoming the “tongue that is licking up the cream of commerce and finance of a continent.”20

Endnotes

1 “Ezra Cooper”: James Sloan Gibbons, The Banks of New-York, Their Dealers, The Clearing House, and the Panic of 1857 (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1859), 62–63.

2 “the whole Commerce,” “does little of her own”: Sven Beckert, The Monied Metropolis: New York City and the Consolidation of the American Bourgeoisie, 1850–1896 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 87–88, 89.

3 “solid men”: John Austin Stevens, The Union Defense Committee of the City of New York: Minutes, Reports and Correspondence (New York: Union Defence Committee, 1885), 3, 40; “There can be no”: Ernest A. McKay, The Civil War and New York City (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1990), 58.

4 “to leave to my”: Beckert, The Monied Metropolis, 113.

5 “I cannot return”: McKay, The Civil War and New York City, 31.

6 “Gentleman, the war must”: J.T.W. Hubbard, For Each, the Strength of All: A History of Banking in the State of New York (New York: NYU Press, 1995), 117.

7 “throw out”: Bray Hammond, Sovereignty and an Empty Purse: Banks and Politics in the Civil War (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1970), 95.

8 “it was the duty,” “bearing a common”: J. W. Schuckers, The Life and Public Services of Salmon Portland Chase (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1874), 279, 290. The term “greenback” was used broadly during the war, sometimes to describe demand notes and National Bank money as well, but it came into wide use to refer to the new legal tender federal money that began to appear in 1862.

9 “the irredeemable and”: Stephen Mihm, A Nation of Counterfeiters: Capitalists, Con Men, and the Making of the United States (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007), 314.

10 “hail with joy”: Hammond, Sovereignty and an Empty Purse, 96.

11 “Working Men,” “Make the U.S. Government,” “six store and,” “colored men,” “laboring classes”: Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer, Jay Cooke: Financier of the Civil War. Volume One (Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs & Company, 1907), 585–587 and illustration facing 585.

12 “thrift, frugality”: Report of the U.S. Congress, Senate Select Committee on the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company, United States Senate, April 2, 1880 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1880), II.

13 “paper, rags”: Charles H. Wesley, Negro Labor in the United States, 1850–1925: A Study of American Economic History (New York, 1927), 143, quoted in Barbara P. Josiah, “Providing for the Future: The World of the African American Depositors of Washington, DC’s Freedmen’s Savings Bank, 1865–1874,” The Journal of African American History 89, no. 1 (Winter 2004): 1–16; http://jstor.org/stable/4134043, 6.

14 “gave Emancipation” quoted in John Martin Davis, “Bankless in Beaufort: A Reexamination of the 1873 Failure of the Freedmans Savings Branch at Beaufort, South Carolina,” The South Carolina History Magazine 104, no. 1 (January 2003): 25–55; http://jstor.org/stable/27570611, 34.

15 “all the hard-earned”: W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Co., 1903), 37.

16 “laden with spoils”: Barnet Schecter, The Devil’s Own Work: The Civil War Draft Riots and the Fight to Reconstruct America (New York: Walker, 2006), 193–194; “On former occasions”: Allan Nevins and Milton Halsey Thomas, eds., The Diary of George Templeton Strong (New York: Macmillan, 1952), Vol. III, 348.

17 “mainspring of rebellion”: Beckert, The Monied Metropolis, 129; “enemies of the government”: McKay, The Civil War and New York City, 175.

18 “has released us”: Beckert, The Monied Metropolis, 120.

19 “Never before did”: Nevins and Thomas, Diary of George Templeton Strong, Vol. III, 574.

20 “tongue that”: Thomas Kessner, Capital City: New York City and the Men Behind America’s Rise to Economic Dominance, 1860–1900 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003), 30.

× 29

× 29 in).

in).