Modern tourism is a recent occurrence in Chinese social life. Even though there is an old tradition of domestic travel within the country, even though great numbers of people moved around during the turmoil created by the Cultural Revolution, mass travel for leisure and vacational purposes started just a few years ago (Richter, 1983; Zhang Qiu et al., 1999).

It was only with the “open door” policies initiated in the late 1970s and in the 1980s that tourism started to grow exponentially (Sofield and Li, 1998). Inbound tourism, both by Chinese living outside the borders of the PRC (the “compatriot” category in China National Tourist Authority’s (CNTA) statistics), and by foreigners replaced the formerly tiny domain of travel and hospitality business limited to political, trade and professional purposes (Zhang, 1997). Domestic tourism has grown since then by leaps and bounds at the same time as the Chinese GDP increased 13.7 times between 1978 and 1999 and per capita GDP passed from RMB 379 to RMB 6,705 – nearly 18 times more – in the same period (Zhang Qiu et al., 2003). In 2003 China’s GDP reached US$1.4 trillion and per capita GDP went up to US$1,100 (World Bank, 2005).

In spite of such vigorous growth, tourism has only recently been taken up as an academic subject by Chinese scholars and institutions of higher learning (Zhang, 2003b). It should not therefore come as a surprise that theoretical reflection on the many dimensions of tourism in China still finds itself at a burgeoning state (Xiao, 2000). Outside the Chinese academia, the attention paid to China’s tourism has not matched its real weight either. A search of the archives of Annals of Tourism Research and Tourism Management, two of the most influential academic journals for travel and tourism, showed that during the past 30 years their combined articles dealing with China totaled 59, including many short items (Aramberri and Xie, 2003b).

In the past, most academic discussions of China’s tourism “have occurred among researchers and writers outside of China, while the opinions and findings of Chinese academics have been hardly heard in the outside world” (Zhang, 2003b, pp. 67–8). For a while, the agenda for tourism research on China was mostly set by foreigners or Chinese scholars working outside the mainland. However, one can see quick changes in the landscape as tourism and travel start to be seen as serious subjects for study and research inside the PRC. A look at the roster of contributors in the two collections on tourism in China edited by Alan Lew and his colleagues (Lew and Yu, 1995; Lew et al., 2003) tells volumes about this trend. The newest book counts a majority of Chinese contributors, even though many of them are active in Western universities. This development is bound to grow in the very near future, as more and more Chinese universities churn out increasing numbers of Master’s and PhDs (Du, 2003).

For the time being, however, there are remarkable differences between academic literature written in Chinese and in English, both in the issues studied and in the way they are handled. Most Chinese contributions focus on trend description, while those in English probe deeper into the meaning and impacts of tourism development. With a familiar distinction, one could say that literature in Chinese remains within the advocacy platform or positivist approach, while literature in English looks at China’s tourism through a cautionary lens (Jafari, 2001). For the time being, quantitative analysis reigns supreme in China (with well-known exceptions such as Wang, 2000), whereas the debate outside the PRC focuses rather on cultural issues, such as national identities, ethnicity and the relation between tourism and modernity. This chapter will attempt a different approach. Starting with a discussion of the most salient trends in present-day Chinese tourism, it will maintain that they pose some theoretical questions that mainstream Western research usually responds to in the wrong way.

In fact, tourism development in China, if one wants to understand it fully, needs reconceptualization in the light of the ongoing discussion on economic development, especially under the label of globalization (Bhagwati, 2004; Easterly, 2001; Friedman, 2005; North, 1981; Sen, 1999; Stiglitz, 2002). Literature on our own field of tourism (see Part 3) often gives the impression that tourism development might be an autonomous field free of a more general anchorage. Close inspection, though, reveals that this powerful illusion often blurs discussion.

Our task in the following pages will therefore be threefold, to:

The authors do not claim to have all the answers to the questions raised; they are persuaded, however, that current research will be better served if we change the framework of our enquiries. This makes it mandatory to develop an explanation that will include some general theories of economics and social history.

A Truly Great Leap Forward

The detailed description of the bare bones of China’s tourism to which so many Chinese scholars have devoted their research efforts has been rewarded with reasonable success. Its main structural aspects are now much better known than they were just a few years ago (Oudiette, 1990). We now consider a short review of its main traits at the inbound, outbound and domestic macro-levels.

Inbound Tourism

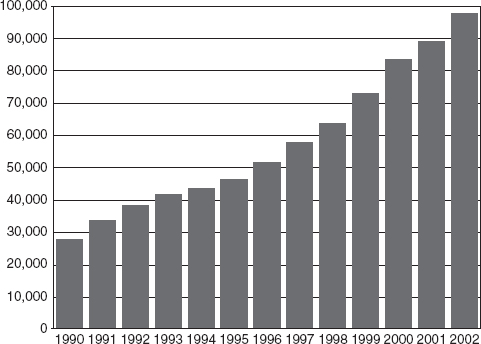

For the past quarter century, inbound tourism to China has grown at a spectacular rate (Gormsen, 1995a). Figure 2.1 graphically shows the steep ascent between 1990 and 2002. Though the SARS outbreak in 2003 brought about a decline in the number of foreign visitors, 2004 recovered growth in a spectacular way. The total number of foreign arrivals reached 109 million, growing 19 per cent over 2003. In this way, China has become the fifth ranking tourist destination in the world.

Figure 2.1 China’s inbound tourism market 1990–2002 (‘000 arrivals).

Source: The Yearbook of China Tourism Statistics (CNTA 2005b)

However, the majority of those visitors did not stay overnight in China. In 2004 only 41.8 million did – 37.7 percent of the total. This is possibly accounted for by the fact that proper foreign arrivals are far fewer than those from Hong Kong and Macao. In spite of being seen by the PRC as constituent parts of its nation, those generating markets are not counted as domestic tourists, but as foreign arrivals.

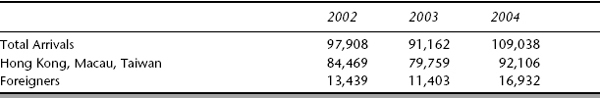

Nearly 85 percent of those 109 million arrivals were Chinese residents in Hong Kong, Macao or Taiwan (Table 2.1). The rest (nearly 17 million in 2004) came from nonChinese markets. A majority (63.4 percent in 2004) originated in Asian nations (Zhang, 2003a). Long-haul visitors have increased from every major source country in the world (CNTA, 2005b).

No matter their ethnic origin, foreign visitors exhibit some similar characteristics: males outnumber females two to one; they are middle-aged and elderly adults; and they concentrate in major cities (Beijing, Shanghai, Xi’an and Guilin), although repeaters increasingly travel to medium-sized and interior cities (Shen, 2003).

Table 2.1 Inbound tourism to China (arrivals in thousands)

Source: CNTA, 2005b; Tourism Forum, 2005

Overseas visitors create a sizeable flow of foreign currency. In 2000, international receipts reached US$16.2 billion, growing by a factor of 61 since 1978. Four years later, they reached US$25.4 billion with a 57 percent growth. Altogether since the 1978 new economic policies international receipts have seen a nearly 100-fold increase (CNTA, 2005b). The World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC) estimates that direct and indirect tourist exports in China reached US$34.2 billion in 2002. This amounts to 7.1 percent of all Chinese exports. One does not need to look much further to understand the importance of tourism for the economic policies of the Chinese government (Tisdell and Wen, 1991).

Outbound Tourism

A growing section of the Chinese population has the means to travel abroad. However, the number of outbound Chinese travelers does not exactly reflect this fact. Until now foreign travel has been subject to a high degree of administrative intervention that limits the number of countries that can be visited and the amount of money that can be spent abroad, thus holding back its expansion.

However, the outbound market has grown significantly together with the increasing liberalization in travel. From 2000 to 2002 the number of Chinese traveling abroad went from 10 million to 15.7 million (CNTA, 2005a; Tourism Forum, 2005). In 2004 it reached 19 million (Xinghua, 2004; WTTC, 2005). It is expected that by 2020 China will be the fourth largest outbound generating country in the world (Zhang Qiu and Heung, 2001; Zhang Qiu et al., 2003).

Lew (2000) thought it probable that China would soon become a growth engine for the whole south and south-east Asian region, a concept that is not just a linguistic utterance, but has the potential to become a theoretical construct apt to be employed in many different contexts.

Domestic Tourism

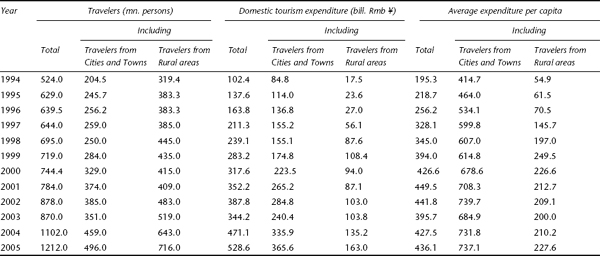

As in most countries, domestic tourism plays a key role in China (Gormsen, 1995b). Table 2.2 synthesizes its development from 1994 to 2000. Except for the 2003 decrease that marked the effects of the SARS crisis, each year has shown considerable growth over the year before. In total, the growth index for domestic tourism in 2004 reached 210 (1994 = 100) with a mean annual increase of 10 percent since the base year.

In their more than 1.1 billion trips, Chinese domestic tourists spent RMB471.1 billion (about 56.8 billion US dollars) revenue, 4.6 times that of 11 years ago (Xinghua, 2005). Rising disposable income due to the quick pace of economic growth plus the introduction of the five-day week and the Golden Weeks have been among the major causes of this impressive expansion (Aramberri and Xie, 2003a; McKahnn, 2001).

The purpose for domestic travel falls into three main categories (Figure 2.2). Although it is difficult to obtain a clear-cut idea, it is possible to suggest that modern mass travel is taking the upper hand, as showed by the great importance of sightseeing and vacationing when they are put together. VFR (visiting friends and relatives) would be closer to older, deferential types of travel, although not completely so. This type of travel also largely reflects the speed of the urbanization process taking place in China. Families in rural areas often receive visits from siblings that migrated to the towns in search of better economic opportunities.

Table 2.2 Domestic tourism in China

Source: CNTA, 2005a

Figure 2.2 Domestic tourism by residents of China by purpose, 2001

Source: The Yearbook of China Tourism Statistics

Conclusion

As usual, quick economic and social changes, even in planned economies, proceed in many disorderly, sometimes contradictory ways. However, drawbacks and shortcomings should not push us to lose track of the ball. They happen because the general landscape is changing quite quickly, not the other way around. The blueprint we have just drafted not only takes the observer on a dizzying rollercoaster ride; it also challenges some notions that underlie most of current academic research. First and foremost, it defies the idea that tourism development (and development tout court) can happen out of the framework of the global capitalist economy. It seems about time that mainstream research should acknowledge the need to look for a different explanation of tourism development, no matter how painful to its main tenets this may be. After all, accounting for facts should be the central interest of academic research. That is where we now have to turn our gaze.

A Truly Great Cultural Revolution

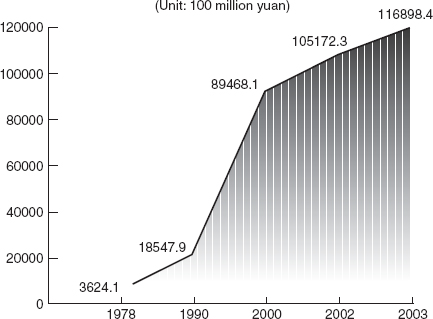

If you don’t have the money, honey, chances are that you will not be traveling. Accordingly, if rapidly increasing numbers of Chinese embark in tourist activities (outbound and domestic), they must have the money – ‘disposable income’ in academic jargon – to do so. This should come as no surprise when you consider the economic path followed by China since 1979 (Figure 2.3).

Since 1998, per capital disposable income of urban households and net income of rural households have increased steadily, at respective annual rates of 7.38 per cent and 3.16 per cent. This has boosted domestic consumption.

(He, 2002, p. 8)

A sizable part of tourism research has great difficulties grappling with this. Conventional wisdom in tourism research holds some truths self-evident, for example:

Figure 2.3 Progression of gross domestic product under economic reform

Source: China Internet Information Center, 2005.

This is the theoretical swamp of tourism-as-dependency that limits our capacity to see beyond the horizon. Although it cannot easily be anchored in facts, this misleading hypothesis weighs heavily on most researchers. Even when it is partially faulted in the details, there are few doubts about its general validity (Sofield, 2003). Such a sanguine approach contrasts with the common aspersions meted out to alternative explanations of development like the modernization hypothesis, customarily charged with maintaining that “there [will] be global convergence towards western capitalism” (ibid., p. 41). However, over the past 60 years global convergence towards capitalism (Western and not) has been the most important world trend. Few policy makers still believe that there are credible alternatives to it.

Current mainstream preconceptions that hark back to the dependency template in tourism research should accordingly be taken with a pinch of salt. As shown by the complex system of traditional Indian travel (Singh, 2004), there are millions of not so affluent travelers in that country, as is conceivably the case in many other developing societies as well. If, additionally, we highlight the impressive expansion of modern domestic tourism, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that our scholarly intuitions need to be reinvented. Tourism is not only the preserve of affluent travelers from developed countries, but also includes increasing numbers in many developing societies. As noted, China is a case in point.

These trends do not fit the dependency template. When it comes to mundane concerns, such as the evolution of the global economy, dependency theories have a dismal predictive record. They were mostly formulated during the 1970s and early 1980s, when the 1950s’ economic boom of the central capitalist countries had come to a relative standstill reviving expectations of its systemic demise. As faithful Marxists, dependency theorists customarily announced the final crisis of capitalism every few hours. Late capitalism, neo-imperialism, or post-colonialism was a system in crisis, probably a terminal one. Capitalist development had become a theoretical oxymoron. Dependency theorists saw it as a closed structure where the unevenness between core and periphery was irreversible and growing fast. Baran (1968), for one, explained that Japan’s economic success since the Meiji era had been the only possible exception. The country’s lack of coveted natural resources kept the imperial powers at bay. Left to itself, Japan was able to grow, but no other country in the periphery would be given a similar chance.

By the time of Baran’s prophecy, however, South Korea was already on its way to become a second exception, quickly relayed by Taiwan, Singapore, Hong Kong and Thailand. Lately, China (followed by India) is treading in the same footsteps. The Chinese economy is now the sixth largest in the world with a GDP of US$1.4 trillion (Economist, 2011) and, according to some forecasts, it will surpass the US as world producer number one by mid-century. The present US debate on the outsourcing of jobs to China and India clearly attests to this changed state of affairs, showing at the same time that globalization works in more complicated ways than forecast by friend or foe.

Increased growth also accounts for changing social structures. Scholars as well as travelers to China will notice that massive social changes are taking place. Above all, a tidal wave of migration from the countryside has flooded the cities, which in turn grow exponentially. Migrants aim at participation in the expanding affluence, as urbanites often take the best part of the newly created riches. At present, China’s urban population accounts for 31 percent of the total, but it is expected to rise to 60 percent within the next 20 years (Li, 2001).

Together with urbanization, consumption standards have risen, mostly in big towns.

Consumers in China today are spending their money on housing, transportation, telecommunications, medical and health care, culture, education and entertainment, leisure and tourism. This is remarkable in that not so long ago basic subsistence was a major concern of many citizens. As expenses for food, clothing and basic necessities dropped, the Engel coefficient (the proportion of food expenses to total consumer spending) of urban residents decreased from 57.5 percent in 1978 to 37.1 percent in 2002; and that of rural residents dropped from 67.7 percent to 45.6 percent.

(People’s Daily, 2005, p. 1)

For the urbanites a good part of that growing income is spent in tourism. Domestic tourism expenditures in China have reached 14 percent of disposable income in urban households (Gu and Liu, 2004).

Urbanization, new consumption patterns and middle-class expansion usually go hand in hand. What are the dimensions of the Chinese middle classes? A local study put them at 19 percent of the population in 2001 – around 250 million (Lu, 2002). They are mostly defined in terms of assets, with a range of RMB 150,000–300,000 (US$18,137–36,275) being at its core. Similar figures have been quoted by BNP Paribas-Peregrine and the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics (Xin, 2004).

Chinese middle classes are made up of leading state and public sector cadres; high and mid–level managers in large and medium-sized enterprises; private entrepreneurs; highly qualified professional, scientific and technical workers; some clerical personnel; and some self-employed. Their growth is seen by the CASS report (Lu, 2002) as evidence that Chinese society is increasingly shaping as an olive, unlike the former pyramidal structure of farmers, workers and intellectuals. The study forecasts that the middle classes will account for 40 percent of the population by 2020.

The CASS report (Lu, 2002) has met some degree of skepticism rooted above all in a discussion of its economics. In 2002 Chinese mean disposable income per person reached RMB 4,520 (US$525) with RMB 8,500 (US$1,050) per city dweller. The top 20 percent of the urbanites (around 100 million people) make an average RMB 15,380 (US$1,900). All of them, therefore, are far from the US$5,000 threshold considered the take-off point for discretionary spending and middle-class lifestyles (Economist, 2011). Others stress the persistent levels of extreme poverty in the country and the low living standards of the peasantry as a whole. Another reason for skepticism is the uneven economic development between coastal, urban eastern China and the backward western part of the country (see an adaptation of this argument to tourism development in Wang, 2004).

However, this array of different criticisms may overreach. Dollar comparisons reflect wide swings in purchasing power, as shown by the Big Mac Index created by The Economist, and the persistence of poverty should not obscure the fact that it happens against a background of increasing social differentiation that makes it less perceivable. Indeed it is accompanied by a rise in inequality. Gu and Liu (2004) have highlighted that in China the Gini coefficient has seen a tenfold increase between 1991 and 2000. But, for many Chinese, it is a welcome sign of the passing away of the previous era where equality meant generalized want.

There is a theoretical puzzle here. On one hand, since 1950, China has claimed to have broken free from the chain of capitalist development. Even today, China defines herself as a non capitalist society with a planned economy. On the other, the capitalist sector (also known as market social economy) has increasing economic clout. How can we account for this turn of events?

One possible line of explanation (Oakes, 1995, 1998) harks back once again to dependency. In this view, two main versions of modernity compete to steer China’s economy. In the first, expressed during the years of Maoist rule, modernity was to be reached as an alternative to the Western model within the national framework of state socialism. The second, the “open door” policies of the post-Mao era, has brought a new form of modernity that may be defined as the modernism of underdevelopment. Oakes does not specify much about the features of this latter strategy, but he points to Hong Kong and Taiwan as the development models preferred by Asian transnational capitalism. Both competing versions of modernity, in his view, provide false roadmaps, and both coincide in promoting China through an equally essentialist strategy. The Maoist path stressed the uniqueness of socialist China, while the second narrative uses a fantasized notion of Chinese tradition as the core for a flexible accumulation of capital. Ever since its inclusion in China’s seventh Five Year Plan (1985–90), tourism development has become so central a part of the second strategy that, if we believe Oakes, Chinese theme parks have become the metaphor through which the country is invited to represent itself. Taking his cue from tourist development in a rural and impoverished area of Guizhou he portends that the tourism industry is appropriating some villages to turn them into life-size theme parks to convey “a landscape of ‘calming certainty’ that legitimizes both the state’s and capital’s narratives of Chinese modernity” (Oakes, 1998, p. 57).

It is difficult to accept this view. It lionizes some economically minor facts such as the expansion of theme parks in China into a key component of macro socio-economic strategies. Additionally, it does not suggest what stuff non-essentialist development strategies are made of, let alone how they might be implemented. The real issue, however, lies at a deeper level. In today’s China there are no two general narratives or strategies vying to steer her development. What we have seen since 1978 is nothing less than the complete discredit and rejection of one of them. Maoist economics based on modernization – through a proletarian revolution with a rural engine; country vs. towns; the peasant-soldier as role model; banning profit; nonstop shake-ups of the state apparatus; and other wishful thinking – have lost the credibility they once held. The experiences of the Great Leap Forward and the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution led the country up a blind alley, turning its economy into a shambles. Deng and his successors came to the realization that, no matter what the dependency theorists might claim, even a country as great as China could not live with its back to the global (capitalist) economy. The “open door” policies drew the necessary consequences.

The new road may be essentialist, but it is not yet possible to determine. At any rate, until now it has delivered a relative degree of material well-being unknown in China since the T’ang dynasty, when the country was far ahead of the rest of the world.

A Different Look

Perhaps there is another way to look at the puzzle. Capitalism may not be as transient a system as some people expected and still expect it to be. Some French critics may have it right when they speak somewhat despairingly of the domination of the pensée unique, another name for the emergence of global capitalism. Far from being in its final stages, it seems that, at least for the foreseeable future, capitalism will be as much of a permanent fact (Desai, 2002) as the Neolithic agricultural revolution has been for centuries. You may or may not like it, but it will not go away.

It is perhaps not easy to see things this way after all the fog created by modern socialist revolutions. Although this is not the place to discuss them in detail, it looks more and more that instead of skipping capitalism they simply delayed its full expansion to later embrace it in an accelerated way. This has been the process in the former Soviet Union, in China, in Vietnam. Gramsci once spoke of the October Revolution as a revolution against Das Kapital. He was not far off the mark. While Marx had no doubts that the dissolution of capitalism would start when and where it would have reached its most complete development, modern socialist revolutions happened in traditional, agrarian societies where capitalism was at a bourgeoning state.

It has been suggested (Skocpol, 1979) that, in spite of the socialist labels their leading elites pinned on themselves, those revolutions followed different ways to the accumulation of capital. The notion had already been circulated at the dawn of the Russian revolution by some Bolsheviks (Bukharin and Preobrazhenskii, 1966; Preobrazhenskii, 1965). With different jargon their thesis may be expressed in the following way: what Marx called primitive capitalist accumulation was not bound to follow the British and American template. Under different historical circumstances, the initial push for the transition of agrarian societies to capitalism might adopt unexpected turns. Where there was not a fully fledged entrepreneurial class to generate the big investments needed and to create the new institutional framework, other social agents would take its place. Bismarckian Germany and Meiji Japan opened the way with their model of a mixed economy with heavy participation by their public bureaucracies and their armies (Skocpol, 1994). Revolutionary Russia and China both had to improvise on the ruins of the old social order; collectivist institutions under the leadership of their communist parties were charged with the task of paving the way to primitive accumulation and successfully forced the peasantry to foot the bill for industrialization. Once this goal was achieved, both societies faced a typically capitalist problem – the gap between productive potential and consumption or how to grow further when consumers have very limited purchasing power. A similar quandary was solved with a turn to consumer-led economy in the US (aka Fordism) at the turn of the twentieth century. When in the 1980s collectivism had clearly run its course in Russia and in China, new formulas had to be found to continue expansion, formulas which were different in each country; we will not focus on how their command economies were dismantled. Our aim is just to stop at highlighting the inner logic of the impressive growth of consumption (including tourist consumption and development) in China that explains the process in a better way than dependency theories can.

One final issue has to be addressed. Critics of mass societies and mass consumption underline that these have been unable to make inequality disappear, and they show that it grows everywhere global capitalism holds sway. To some extent this is a truism, like criticizing the Pope for believing in God. Under capitalism, as Desai (2002, p. 297) translates from Adam Smith, “inequality is the spur to the growth of productivity,” productivity the spur to growing disposable income, and disposable income the spur to, among other things, an increase of tourism.

Whether this should be seen as good or bad is an open question that we do not try to address. In our view, the really intriguing problem is how, and above all, why consumer-led capitalism, for all its undeniable inequalities, is seen as a legitimate way of producing and distributing needed goods and services for increasing millions of people.

Some Foucauldian researchers point to normalization and panopticon-like surveillance as the key for this ample social consensus in post-revolutionary societies (Foucault, 1995; Haugaard, 2002; Ransom, 1997). We disagree. In our view two reasons are considerably more central. The first has to do with the experiences of the recent past. No primitive accumulation proceeds smoothly; the rule is exactly the opposite. Once it is over, few people want to go back to the previous revolutionary excitement and its revolutionary exactions.

The second has to do with an old fact well know to sociologists – relative deprivation (Blau, 1986; Riskin et al., 2001; Tilly, 1996). Most Chinese consumers may not have yet the disposable income to buy as many big ticket items as Europeans or Americans or more affluent Chinese do. However, their consumption has definitely increased relative to that of the older generation. Great numbers experience better living conditions. Supermarkets, domestic labor saving devices, affordable and fashionable clothing, air-conditioners, better transportation systems, and, for many, new cars and new homes have become part of everyday life. Vacations are also spreading fast.

What about those lagging behind? For the time being they seem to think that a more comfortable life can also be their lot. This is not a tangible reward. In fact, many will not make it. Relative deprivation, however, works in many ways. It may be a powerful source of revolt, as usually happens when a majority of people feel that the roads to personal and collective improvement are blocked. But it can also act as a prod for social cohesion. When you see that your neighbors prosper, you readily feel that something similar may happen in your case. Equality in the past often meant abysmal poverty for all; today relative inequality opens the way to upward mobility. What might prevent you from sharing in the bounty if you or your siblings happen to obtain the skills demanded by the new economy?

Mass tourism plays a modest though no less important part in the legitimation of consumerled capitalism. The billion plus domestic and outbound Chinese travelers in 2004 and 2005 do not seem to have many qualms about the system that made their trips possible. Perhaps one day their attitudes, expectations and reasons will be understood by the academic community in a non-judgmental way. On our side, we are convinced it is about time to start doing so.

Appadurai, A. (1996) Modernity at large: Cultural dimensions of globalization. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press

Aramberri, J. and Xie, Y. (2003a) ‘Off the beaten theoretical track: Domestic tourism in China’. Tourism Recreation Research, 28(1), 2

Aramberri, J. and Xie, Y. (2003b) ‘Zhongguo Lvyou Yanjiu de Duowei Shiye: Dui Guonei yu Guowai Xiangguang Wenxian de Pingshu’ (Multi-vision on Chinese tourism research: Comment on the domestic and foreign relevant literature). Tourism Tribune, 6, 14–20

Baran, P. A. (1968) The political economy of growth (2nd edn). New York: Monthly Review Press

Bhagwati, J. N. (2004) In defense of globalization. New York: Oxford University Press

Blau, P. M. (1986) Exchange and power in social life. New York: J. Wiley

Bukharin, N. I. and Preobrazhenskii, E. A. (1966) The ABC of communism: A popular explanation of the program of the Communist Party of Russia. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press

China Internet Information Center (2005) Overview. Retrieved on 15 November 2011, from http://www.china.org.cn/english/features/china2004/107000.htm

Chu, Y. (1994) ‘Evaluation of sightseeing areas in China’. Annals of Tourism Research, 21(4), 837–39.

CNTA (2005a) ‘Facts and figures: Outbound tourism’. China National Tourist Authority. Retrieved 20 November 2011, from http://en.cnta.gov.cn/html/2008-11/2008-11-9-21-40-54934.html

CNTA (2005b) ‘China Inbound Travel Statistics for 2004’. China National Tourist Authority. Retrieved on 20 November 2011, from http://www.cnta.gov.cn/html/2008-6/2008-6-2-21-28-45-89.html; http://www.cnta.gov.cn/html/2008-6/2008-6-2-21-28-44-72.html; http://www.cnta.gov.cn/html/2008-6/2008-6-2-21-28-43-61.html

Crick, M. (1989) ‘Representations of international tourism in the social sciences: Sun, sex, sights, savings and servility’. Annual Review of Anthropology, 18, 307–44

Crick, M. (1995) ‘The anthropologist as tourist: An identity in question’. In M. F. Lanfant, J. B. Allcock and E. M. Bruner (eds) International tourism: Identity and change. London: Sage Publications, pp. 205–23

Dann, G. M. S. (1996a) ‘Tourists’ images of a destination: An alternative analysis’. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 5(1/2), 41–55

Dann, G. M. S. (1996b) ‘The people of tourist brochures’. In T. Selwyn (ed.) The tourist image: Myths and myth making in tourism. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons, pp. 61–82

Desai, M. (2002) Marx’s revenge: The resurgence of capitalism and the death of statist socialism. London: Verso

Du, J. (2003) ‘Reforms and development of higher tourism education in China’. Journal of Teaching in Travel and Tourism, 3(1), 103–13

Easterly, W. R. (2001) The elusive quest for growth: Economists’ adventures and misadventures in the tropics. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press

Economist (2011) ‘Currency comparisons, to go’. The Economist. Retrieved 5 December 2011, from http://www.economist.com/blogs/dailychart/2011/07/big-mac-index

Foucault, M. (1995) Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison (2nd edn). New York: Vintage Books

Friedman, B. M. (2005) The moral consequences of economic growth. New York: Knopf

Gormsen, E. (1995a) ‘International tourism in China: Its organization and socio-economic impact’. In A. A. Lew and L. Yu (eds) Tourism in China: Geographic, political, and economic perspectives. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, pp. 63–88

Gormsen, E. (1995b) ‘Travel behavior and the impacts of domestic tourism in China’. In A. A. Lew and L. Yu (eds) Tourism in China: Geographic, political, and economic perspectives. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, pp.131–40

Graburn, N. H. H. (1989) ‘Tourism: The sacred journey’. In V. L. Smith (ed.) Hosts and guests: The anthropology of tourism (2nd edn). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 21–36

Graburn, N. H. H. (2001) ‘Secular ritual: A general theory of tourism’. In V. L. Smith and M. Brent (eds) Hosts and guests revisited: Tourism issues of the 21st century. New York: Cognizant Communication Co., pp. 42–50

Gu, H. and Liu, D. (2004) ‘The relationship between resident income and domestic tourism in China’. Tourism Recreation Research, 29(2), 25–33.

Haugaard, M. (2002) Power: A reader. Manchester: Manchester University Press

He, G. (2002) ‘China’s economic restructuring and banking reform’. Yomiuri International Economic Society (eds) Proceedings of the 11th Symposium by IIMA: Emerging China and the Asian economy in the coming decade, pp. 6–14. Retrieved 15 November 2011, from http://www.iima.or.jp/pdf/paper12e.pdf

Jafari, J. (2001) ‘The scientification of tourism’. In V. L. Smith and M. Brent (eds) Hosts and guests revisited: Tourism issues of the 21st century. New York: Cognizant Communication Co., pp. 28–41

Jeffrey, D. and Xie, Y. (1995) ‘The UK market for tourism in China’. Annals of Tourism Research, 22(4), 857–76

Lew, A. A. (2000) ‘China: A growth engine for Asian tourism’. In C. M. Hall and S. Page (eds) Tourism in South and Southeast Asia: Issues and cases. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, pp. 268–85

Lew, A. A. and Yu, L. (eds) (1995) Tourism in China: Geographic, political, and economic perspectives. Boulder, CO: Westview Press

Lew, A. A., Yu, L., Ap, J. and Zhang, G. (eds) (2003) Tourism in China. New York: Haworth Hospitality Press

Li, H. (2001) ‘China’s urbanization rate to reach 60% in 20 years’. People’s Daily Online, 17 May. Retrieved 11 November 2011, from http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/english/200105/17/eng20010517_70205.html

Lindberg, K., Tisdell, C. andXue, D. (2003) ‘Ecotourism in China’s nature reserves’. In A. A. Lew, L. Yu, J. Ap and G. Zhang (eds) Tourism in China. New York: Haworth Hospitality Press, pp. 103–28

Lu, X. (2002) Dangdai Zhongguo Shehui Jieceng Yanjiu Baogao (A Report on the Study of Contemporary China’s Social Strata). Beijing: Shehui Kexue Wenxian Chubanshe (Social Sciences Literature Press)

MacCannell, D. (1999) The tourist: A new theory of the leisure class (3rd edn). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press

MacCannell, D. (2001) ‘The commodification of culture’. In V. L. Smith and M. Brent (eds) Hosts and guests revisited: Tourism issues of the 21st century. New York: Cognizant Communication Co., pp. 380–90

McKahnn, C. F. (2001) ‘The good, the bad and the ugly: Observations and reflections on tourism development in Lijiang, China’. In C. B. Tan, S. C. H. Cheung and Y. Hui (eds) Tourism, anthropology and China: In memory of Professor Wang Zhusheng. Bangkok: White Lotus Press, pp. 147–66

Mak, B. (2003) ‘China’s tourist transportation: Air, land and water’. In A. A. Lew, L. Yu, J. Ap and G. Zhang (eds) Tourism in China. New York: Haworth Hospitality Press, pp. 165–94

Nash, D. (1996) Anthropology of tourism. Kidlington: Pergamon

North, D. C. (1981) Structure and change in economic history. New York: Norton

Oakes, T. (1998) Tourism and modernity in China. New York: Routledge

Oakes, T. S. (1995) ‘Tourism in Guizhou: The legacy of internal colonialism’. In A. A. Lew and L. Yu (eds) Tourism in China: Geographic, political, and economic perspectives. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, pp. 203–22

Oudiette, V. (1990) ‘International tourism in China’. Annals of Tourism Research, 17(1), 123–32

People’s Daily (2005) ‘Consumption’. People’s Daily. Retrieved 15 November 2011, from http://english.people.com.cn/data/China_in_brief/Lifestyle/Consumption.html

Preobrazhenskii, E. (1965)[1928] The new economics, trans. B. Pearce. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Ransom, J. S. (1997) Foucault’s discipline: The politics of subjectivity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press

Richter, L. K. (1983) ‘Political implications of Chinese tourism policy’. Annals of Tourism Research, 10(3), 395–413

Riskin, C, Zhao, R. and Li, S. (eds) (2001) China’s retreat from equality: Income distribution and economic transition. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe

Sen, A. K. (1999) Development as freedom. New York: Oxford University Press

Shen, X. (2003) ‘Short- and long-haul international tourists to China’. In A. A. Lew, L. Yu, J. Ap and G. Zhang (eds) Tourism in China. New York: Haworth Hospitality Press, pp. 237–62

Singh, S. (2004) ‘India’s domestic tourism: Chaos/crisis/challenge?’. Tourism Recreation Research, 29(2), 35–46

Skocpol, T. (1979) States and social revolutions: A comparative analysis of France, Russia, and China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Skocpol, T. (1994) Social revolutions in the modern world. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sofield, T. H. B. (2003) Empowerment for sustainable tourism development. Amsterdam: Pergamon

Sofield, T. H. B. and Li, F. M. S. (1998) ‘Tourism development and cultural policies in China’. Annals of Tourism Research, 25(2), 362–92

Stiglitz, J. E. (2002) Globalization and its discontents. New York: W. W. Norton

Tilly, C. (ed.) (1996) Citizenship, identity and social history. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Tisdell, C. and Wen, J. (1991) ‘Foreign tourism as an element in PR China’s economic development strategy’. Tourism Management, 12(1), 55–67

Tourism Forum (2005) ‘The impact of travel and tourism on jobs and the economy: China and China Hong Kong SAR’. Retrieved 21 November 2011, from http://www.tourismforum.scb.se/papers/PapersSelected/TSA/Paper1WTTC/China_Hong_Kong.pdf

van den Berghe, P. L. (1994) The quest for the other: Ethnic tourism in San Cristobal, Mexico. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press

Wang, N. (2000) Tourism and modernity: A sociological analysis. New York: Pergamon

Wang, N. (2004) ‘The rise of touristic consumerism in urban China’. Tourism Recreation Research, 29(2), 47–58

Wang, S. and Ap, J. (2003) ‘Tourism marketing in the People’s Republic of China’. In A. A. Lew, L. Yu, J. Ap and G. Zhang (eds) Tourism in China. New York: Haworth Hospitality Press, pp. 217–36

Wei, Q. (2003) ‘Travel agencies in China at the turn of the millennium’. In A. A. Lew, L. Yu, J. Ap and G. Zhang (eds) Tourism in China. New York: Haworth Hospitality Press, pp. 143–64

World Bank (2005) ‘China at a glance’. World Bank. Retrieved 20 November 2011, from http://devdata.worldbank.org/AAG/chn_aag.pdf

WTTC (World Trade and Tourism Council) (2005) ‘Competition monitor: Human tourism: International tourist departures’. Retrieved 24 April 2005, from http://wttc.org/2004tsa/frameset2a.htm

Xiao, H. (2000) ‘China’s tourism education into the 21st century’. Annals of Tourism Research, 27(4), 1052–5.

Xin, Z. (2004) ‘Dissecting China’s “Middle Class”’. China Daily, 27 October. Retrieved 5 December 2011, from http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/english/doc/200410/27/content_386060.htm

Xinghua (2004) Chinese outbound travel soars 63.7%. Xinghua News Agency, 17 September. Retrieved 11 November 2011, from http://www.china.org.cn/english/2004/Sep/107371.htm

Xinghua (2005) Chinese domestic tourism income quadruples in ten years. Xinghua News Agency, 18 April. Retrieved 15 April 2011, from http://www.china.org.cn/english/travel/126130.htm

Yu, L. (2003) ‘Critical issues in China’s hotel industry’. In A. A. Lew, L. Yu, J. Ap and G. Zhang (eds) Tourism in China. New York: Haworth Hospitality Press, pp. 129–42

Zhang Qiu, H. and Heung, V. C. S. (2001) ‘The emergence of the mainland Chinese outbound travel market and its implications for tourism marketing’. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 8(1), 7–12

Zhang Qiu, H., Chong, K. and Ap, J. (1999) ‘An analysis of tourism policy development in modern China’. Tourism Management, 20(4), 471–85

Zhang Qiu, H., Jenkins, C. L. and Qu, H. (2003) ‘Mainland Chinese outbound travel to Hong Kong and its implications’. In A. A. Lew, L. Yu, J. Ap and G. Zhang (eds) Tourism in China. New York: Haworth Hospitality Press, pp. 277–96

Zhang, G. (2003a) ‘China’s tourism since 1978: Policies, experiences and lessons learned’. In A. A. Lew, L. Yu, J. Ap and G. Zhang (eds) Tourism in China. New York: Haworth Hospitality Press, pp. 13–34

Zhang, G. (2003b) ‘Tourism research in China’. In A. A. Lew, L. Yu, J. Ap and G. Zhang (eds) Tourism in China. New York: Haworth Hospitality Press, pp. 67–82

Zhang, L. (1991) ‘China’s travel agency industry’. Tourism Management, 12(4), 360–62

Zhang, W. (1997) ‘China’s domestic tourism: Impetus, development and trends’. Tourism Management, 18(8), 565–71