It is necessary to start with a definition. The term ‘tourism planning’, often seen in literature, has not been frequently defined. Even though Gunn (1988) and C. M. Hall (2000a) have defined planning, and Inskeep (1991) has listed eight elements of tourism planning, these authors did not define the term explicitly in their books on tourism planning. In the limited number of works that include a definition, tourism planning has been defined in various ways. Some definitions have a predominantly economic focus and refer to tourism planning as the provision of guidance for the use of tourism assets and the development of tourism in a marketable way (e.g. Lickorish and Jenkins, 1997). Some have emphasized the scope of tourism planning, such as the definition of Evans (2000, p. 308) which was modified from that of Page (1995), as ‘a process considering social, economic and environmental issues in a spatial context in terms of development, conservation and land use.’ Sometimes tourism planning has been defined from mixed perspectives. For example, Wahab and Pigram (1997, p. 279) indicated that the term referred to a process that leads development to be ‘adaptive to the needs of the tourists, responsive to the needs of local communities, and socio-economically, culturally and environmentally sound.’ Timothy (1999, p. 371) defined it in a way that is more suitable for application to destination areas and their residents: ‘Tourism planning is viewed as a way of maximizing the benefits of tourism to an area and mitigating problems that might occur as a result of development.’ However, Wall (1996, p. 41) has suggested that planning is a political process that ‘empowers some and disadvantages others,’ and that maximizing benefits and minimizing costs cannot happen at the same time. Timothy’s definition is somewhat ambiguous on this point. In this paper, the definitions of Murphy (1985) and Getz (1987) have been combined so that tourism planning is regarded as being concerned with anticipating and regulating changes in the tourism system and integrating it with broader-scale development. It is a process which seeks to optimize the potential contribution of tourism to human welfare and environmental quality.

The origin and evolution of tourism planning are closely linked with the history of both planning and tourism. Modern planning arose at the turn of the nineteenth century in the West (Campbell and Fainstein, 1996). In the Second World War, it was established as a profession and the rational comprehensive planning model (RCP) became a theoretical foundation of planning (Klosterman, 1996). In the 1960s and 1970s, a host of problems, such as slum clearance, urban sprawl and inadequate housing, stimulated the initial demand for public participation in planning (P. G. Hall 1980; Lanfant and Graburn, 1992; Taylor, 1998). The emergence of the ‘participation era’ (Grant, 1989) or the ‘return to the local’ (Lanfant and Graburn, 1992) ultimately established public participation as one of the most important components in the Western planning process. A host of different approaches to planning emerged, including incremental planning (Lindblom, 1959), advocacy planning (Davidoff, 1965), transactive planning (Davidoff, 1975), integrated planning (Conyers and Hills, 1984), strategic planning (J. L. Kaufman and Jacobs, 1987), and collaboration planning (Healey, 1992). Each of these approaches, to varying degrees, encourages planners to create a more meaningful role for the public in planning processes and decision making.

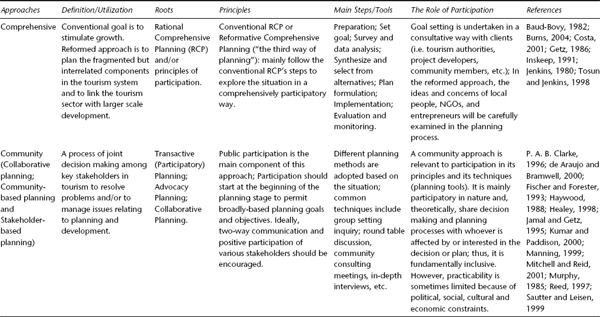

Burns (1999) and Costa (2001) have reported a somewhat similar path in the evolution of tourism planning. In the post-war period and into the 1960s, increased disposable income and technological progress such as in aircraft design and expanding car ownership stimulated the growth of mass tourism. Tourism master planning in the mode of rational comprehensive planning emerged at the end of this period. It was aimed at promoting tourism at almost all costs and usually lacked a critical analysis of the tourism sector. With the continual growth of mass tourism, master planning approached its apex in the 1970s but there was commonly a lack of political will in shaping development to the destination’s own needs (Burns, 1999). Many tourism destinations formulated their master plans (e.g. Israel’s 1976 tourism master plan and Jordan’s 1981–85 tourism development plan: see Travis, 2011) during this period. In the 1980s, a decade after their urban planning counterparts, alternative tourism planning approaches were developed associated with the growing awareness of negative socio-cultural and environmental impacts at destinations, and the emerging demands for more than ‘four S’s’ tourism (sea, sand, sun, sex) among experienced tourists (Burns, 1999; Costa, 2001). The major tourism planning approaches have been summarized in Table 12.1 to facilitate synthesis and comparison.

The emphasis on tourism master planning has declined in most developing countries and been replaced by an emphasis on product development and marketing. In contrast, as Haywood (1988) and Wall (1996) have pointed out, comprehensive tourism planning is still widespread in less-developed countries. The national tourism development plan in Fiji in 1973 is one example (Inskeep, 1991). In this case, the planning team (including UNDP and World Bank experts) examined the physical environment and recommended various physical aspects of beach tourism development in Fiji. Although the district governments were carefully consulted, obvious public participation did not happen in the Fiji case, partly because the master plan was constructed at the national level. A different case of comprehensive tourism planning occurred in Alberta, Canada (Gunn, 1988). The planning task was to prepare a master plan that would include a comprehensive review of tourism in Alberta to understand its history, marketing, world position and identify future potential. During the planning process in 1984, there was significant involvement of the private sector through surveys, and this helped to establish a more intimate affiliation between the public and the private sectors.

More recently, the community approach to tourism planning has received much emphasis. This reflects a change in scale from national and provincial/state plans to a more local focus. Three sub-approaches, as shown in Table 12.1, can be identified. Although the three terms are sometimes used interchangeably (as in Jamal and Getz, 1995), they are separated here according to the way that they have been used by specific authors. First, a collaborative approach was used in formulating the Hope Valley Visitor Management Plan in Britain (Bramwell and Sharman, 1999). The planning process, including a series of collective discussions, involved many stakeholder groups and adopted various participatory techniques. Partially as a result of the process that was adopted, residents broadly supported the plan. An often-cited successful community-based tourism planning case was that in Waikiki, Hawaii. Sheldon and Abenoja (2001) have commented on the extensive efforts, such as the large number of long-term resident attitude studies that were directed towards involving local residents in planning. Successful round-table stakeholder-based tourism planning was undertaken in several sub-regions in British Columbia (Murphy, 1988). Stakeholder workshops brought various stakeholders in the tourism industry (mainly community NGOs and business groups) together to discuss their own expected futures. According to Murphy, a synergistic partnership was established which helped to balance gains in development with other community aspirations.

Table 12.1 Tourism planning approaches

An integrated planning approach was adopted by the Republic of South Africa as a means to unite sectors, geographic areas and private organizations in a way that would promote sustainable tourism (Gauteng Tourism Authority, 2003). The planning task was undertaken with the assistance of, and under the consultation of, the British Department of International Development. Economic, social and environmental guidelines were formulated to direct future tourism policy making.

A strategic planning approach was used by Fletcher and Cooper (1996) in Hungary. The main goals that were identified by local tourism authorities were to reduce the pressure of tourism on Budapest by widening the regional distribution of tourists and spreading out the economic benefits. Following an environmental review, Szolnok County was chosen for emphasis. Tourism attractions and facilities were ‘discovered’ and likely problems were identified during a community survey that was conducted with local NGOs. Goals were then identified as the development or redevelopment of facilities and attractions to meet development needs, while mitigating the risks of social and environmental damage. Short-, medium- and long-term action strategies were then formulated. They relied upon a close relationship between tourism authorities and local organizations, especially local entrepreneurs, for their implementation.

Alternative tourism planning approaches include various emphases, such as ecotourism planning and green, rural, and agricultural tourism planning. An example of such alternative tourism planning is seen in the development of ecotourism in Montserrat (Weaver, 1995). After government departments (Tourism, Agriculture, Trade and Environment) agreed to promote ecotourism, detailed studies were carried out and plans were formulated by external agencies (UNDP) together with local NGOs. In another example, the Korean government decided to promote rural tourism as they were impressed by the successful experience of Japan (Hong et al., 2003). Aiming at both economic returns and raising cultural awareness among urban and rural people, environmentally friendly, small-scale development projects with special events were organized by the Korean government together with resident groups.

Sustainable development has been identified as yet another tourism planning approach by Tosun and Jenkins (1998), C. M. Hall (2000a) and Baidal (2004). However, the practical application of this approach remains in doubt for it is not easy to find examples of its adoption (but see Martopo and Mitchell, 1995). As shown in Table 12.1, sustainability has often been treated as a concept or a goal in tourism planning, rather than an approach to undertaking planning.

A recurring theme within the above approaches/concepts, as summarized in Table 12.1, is the advocacy of participation in decision-making and planning processes. Obviously, it is an important concept and the origin and the definition of participation in planning needs clarification. Participation in tourism planning has been suggested as a way to promote sustainability, to balance economic and social development, to integrate destination planning, to ensure that a ‘sense of place’ is maintained, to foster a better understanding of complex situations, to develop a common value base, and to increase recognition of interdependence among destination stakeholders (Bahaire and Elliott-White, 1999; Bramwell and Lane, 1993; Gill, 1997; C. M. Hall, 2000b; Jamal and Getz, 1997; Timothy, 1998; Wall, 1997).

This discussion has provided a brief overview of the evolution of tourism planning and the labels that have been assigned to different approaches. A common underpinning theme that has emerged in the developed world is increased attention to participation in planning (see Haywood, 1988; Inskeep, 1991; Keogh, 1990; Murphy, 1985, 1988; Simmons, 1994). Tosun (2000) argued that this has occurred since the 1960s because of the increased needs of governments to respond to community actions. Participation, which is now one of the most important concepts in Western planning, has been defined in various ways: as a process of redistributing power that enables those who hitherto were excluded to control the decision-making process (Arai, 1996; M. Kaufman, 1997; Willis, 1995); as collaborative influence and control over decisions by stakeholders (World Bank, 1996); and as one goal of social change and a method of bringing about change (M. Kaufman, 1997). Researchers, however, have also pointed out that, in some cases, participation results from a top-down decision that is directed or permitted by clients of the planning process with (or without) the intention of sharing the power (Cuthbertson, 1983; Roy, 1998). Thus, participation in this situation is defined as activities undertaken by a planning or management agency to provide the opportunity for local communities to influence decisions regarding developments which will affect their lives (Arai, 1996). Based on the above definitions and the characteristics of the tourism planning approaches that were discussed earlier, participation is defined here as a political process that enables people to take control over the development initiatives, decisions and resources that affect them.

In summary, as a principle of Western planning, participation refers mainly to the process of involving various stakeholders in decision making. In tourism it has been viewed as being a means of improving planning and making development more acceptable. For example, according to advocates of a community approach to planning, participation of the community in negotiating distribution issues (means) leads to a more reasonable distribution of local gains from tourism (ends) (Haywood, 1988; Keogh, 1990; Murphy, 1983, 1985, 1988, 1992; Tosun and Jenkins, 1996). However, participation in the West is not merely a means; as a sign of democracy, it is also an end in itself (M. Kaufman, 1997). Furthermore, Western researchers discuss participation not merely as sharing in decision making; rather they also discuss participation in terms of sharing in the benefits, such as the discussions of Long and Wall (1996) of cruises and homestays, and Timothy (1999) about street businesses in Indonesia. Benefit-sharing has often been seen as being an outcome of good planning and development, usually involving participation in decision making, or as an item in evaluating tourism impacts.

The purpose of this communication is to examine the evolution of tourism planning in China and, against the background to tourism planning that has been presented above, to comment upon the possible relevance of Western planning models to China. The evidence upon which this communication is based is varied.

First, a review of relevant literature, both Western and Chinese, was undertaken, the former being partially reported above. Second, the authors’ varied backgrounds and experiences have been drawn on to inform our discussion. The first author is a graduate in construction management from Tongji University in Shanghai and she completed a Master’s degree in Planning at the University of Waterloo. Her thesis research was concerned with the displacement of a Li minority community in Hainan by the development of a tourism resort. She is building upon this in her doctoral research to examine ways in which similar communities might become more involved in and obtain greater benefits from the tourism developments that are occurring around them.

The second author has been involved in a variety of activities related to tourism, environment and development in China for some 10 years and, prior to that, participated in a number of large planning and development endeavours elsewhere in Asia. In particular, he has directed a five-year project in Hainan on coastal zone management with the overall objective of enhancing the capabilities of the provincial government in Hainan to manage the growing pressures on its coast. One of these pressures is tourism. He directed the Ecoplan China project that has the goal of enhancing the local capacity to undertake environmental planning and management in Hainan as well as elsewhere in China. Both projects have been funded by the Canadian International Agency and are large multi-year initiatives with a variety of partners from universities, government and the private sector, both in Canada and China. He has also been involved in the development of a biodiversity strategy for Inner Mongolia (essentially nature reserve planning and management) as well as tourism plans for Jiangsu, Henan, Hunan and Dalian and a number of other more specific related activities.

Few planning cases in China follow the Western style of planning; however, ‘few’ does not mean ‘none’. Several planning cases in China, although not primarily in the field of tourism, can be identified that have used approaches that are similar to those that have been described above. For example, stakeholder-based strategic tourism planning was undertaken in Leshan, China (W. Zhang, 2003). Funded by the United Nations, the project, incorporating various stakeholder groups (government, local business, residents, etc.) through focus groups, surveys and household interviews, identified a series of strategies to protect a World Heritage Site. Another illustration is an IDRC-funded (International Development Research Centre, Canada) agricultural planning project conducted in Yunnan and Guizhou Provinces (Vernooy et al., 2003). As part of the planning process, the rural people were actively involved in identifying their present situation and their urgent needs to improve household livelihoods, and in formulating action plans to address these needs. A further example is an integrated planning project about managing coastal zones in Xiamen, led by UNDP, IMO and GEF (Lau, 2003). In this project, various levels and sectors of government, participating together in workshops, identified problems and management issues, desirable outcomes and designed implementation plans. Thus, public participation in planning along Western lines is possible in China, particularly if it is facilitated by international agencies. Yet, in the literature, the only non-externally assisted planning project in China adopting a similar approach was a community-based land-use planning case in Shanghai, the wealthiest and most modern municipality in the country. There, various urban districts, streets, offices and business associations participated in deciding upon the new land regulations (G. R. Zhang, 2003).

The long-term effects of these various planning initiatives and approaches are hard to determine. As Pretty (1995) argued, the local people often are unable to maintain participation practices once the flow of external incentives stops. Thus, as some researchers have suggested, perhaps it is true that locally established planning practices may last longer when compared with the borrowed approaches, because the latter may not meet local planning needs (Alipour, 1996; de Kadt, 1979; Tosun and Jenkins, 1998). To further explore this question, it is necessary to examine local planning practices in China.

Urban planning in China dates back to the imperial era, when grand capital cities were constructed in accordance with the feudal ideology of social order and hierarchy (Yeh and Wu, 1999). However, it was not until 1989 that the enactment of the City Planning Act established a comprehensive urban planning system in China, to prepare ‘rational’ city plans to meet the needs of developing socialist modernization (T. Zhang, 2002). Comprehensive planning in China, emphasizing the formulation of land-use plan documents, with different levels of detail and functions, in a top-down process (ranging from urban system plans to detail construction plans), is different from Western rational planning. Comprehensive planning in China attempts to manipulate regional spatial development, and there are no concrete measures to link the planning ‘structures’ with resource allocation, socio-economic policies or the enforcement of development control (Yeh and Wu, 1999).

With stronger emphasis on economic development and severe competition between municipalities to attract external investment, pressure to speed up development, and an urgent need to have enhanced ‘performance’, government officials have had to accept gradually that investors and developers are influential groups in planning and development processes in China. This trend is accelerated because planning institutions are gradually becoming more independent of the government and because the services provided by planners are now more and more user-oriented (T. Zhang, 2002). Furthermore, the prevalent closed-door plan-making process (i.e. no public consultation) and the lack of effective monitoring often give politicians and even planners an excuse to bypass planning controls in order to cater for the interests of developers (Yeh and Wu, 1999). In order to reduce domination of development by the minority and to help promote a ‘cleaner’ government, a greater awareness is now emerging of the need to promote popular participation and monitoring within the planning process. However, to date, these are merely ideas in China (T. Zhang, 2002). T. Zhang’s interviews with Chinese planners clearly showed that they had more interest in sharing power with the top than with the bottom. In the words of Yeh and Wu (1999, p. 236):

In the top-down plan making process, there is inadequate public participation. This does not mean that public participation is explicitly prohibited. But, due to the extremely immobilized local politics, the channel for public participation does not exist and public participation has no real meaning in the context where negotiations mainly take place among government agencies or between government and private investors.

More specifically with respect to tourism, according to the China National Tourism Administration, tourism planning in China is a process of establishing development goals according to the history and present situation of the tourism industry and the requirement of the market, and coordinating and managing the main factors of the tourism sector in order to achieve the goals. As interpreted by Bao and Chu (1999), planning for tourism zones should take into account the carrying capacity, tourists’ behaviours and demands, and the economic, social and environmental situations of the locality. However, as Wall (1995) has argued, comprehensive tourism plans in many less-developed countries, focusing mainly on physical planning and the formal employment sectors, are formulated primarily to satisfy the aspirations of higher-level administrations and to attract investors. China is one such place.

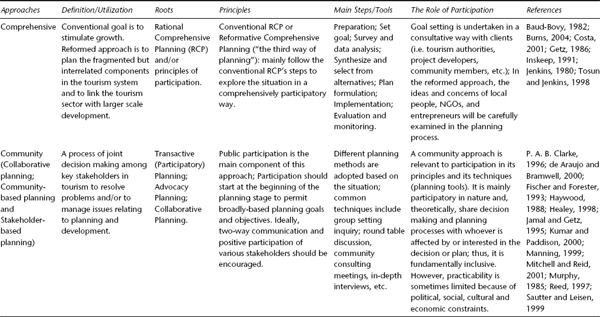

Stages of tourism development in China have been summarized in Table 12.2. As show in this Table, tourism planning started in the 1980s. It was developed without theoretical support or unified standards; the planners made plans that reflected their disciplinary backgrounds (Bao and Chu, 1999). The speciality of urban planning, emphasizing construction of infrastructure, had the biggest influence on tourism planning before the mid-1990s (Bao, 2000). The plans concentrated on attractions, hotels, water and electricity supplies, and roads and transportation (Cai, 1999).

Table 12.2 Stages of tourism development in China

As the problems of such tourism developments were increasingly recognized, especially issues associated with rapid growth (which is still the dominant emphasis), discussion about market supply and demand and the main components of the tourism sector, such as transportation, accommodation, tours, entertainment and shopping, increased (Bao and Chu, 1999). Under the influence of the catchword ‘sustainability’, tourism planning at the turn of century also began to focus on the use and protection of natural resources (Bao, 2000). However, as shown in Table 12.2, no obvious intent to share planning and decision-making powers more broadly can be perceived. Moreover, the planning approach that has been adopted is essentially silent on the negative social impacts of tourism and on distribution issues and, as a result, is limited in its capacity to improve people’s lives (HDDR, 2003). When investment is emphasized in development, more equal benefit-sharing is usually overlooked: those who have resources to input have a greater chance of participating in the development and enjoying its fruits. One section of the population that, among others, has been left behind by this type of planning and development is the rural population in poor regions.

More than 800 million people live in the rural areas of China. They account for over 65 per cent of the total population of the country. Although China has experienced great progress in people’s quality of life, development over the past 20 years has led to unbalanced conditions between urban and rural areas (and between east and west), and the plight of rural areas in poor provinces is too serious to ignore (Han, 2004). Following Deng’s policy whereby ‘a part of the population will become rich first through development’, the senior government officials decided to encourage large-scale, rapid development with the main purpose of stimulating growth. Because many rural areas in poor regions were remote and lacking in basic infrastructure and development opportunities, and because poor people in rural areas lacked tangible resources, such as capital, these people were typically left behind when fast growth occurred in the cities of the eastern seaboard. Studies in 1999 showed that the growth elasticity of income of the lowest quintile of the Chinese population was only 0.308, suggesting that the poor did not benefit even half as much from growth as the richer segments of society (Gang and Kruse, 2003). Within this section of the population, 42 million remained in absolute poverty in 1999 and another 350 million were labelled as poor. Most of these people live in rural areas where limited natural resources set considerable constraints on employment in agriculture (Q. L. Chen, 2002).

Poor rural people are often excluded from the planning process. They do not have a Danwei (collective workplace) to which to report their concerns, and they live far away from the large urban areas, the places where the decisions are made. This also suggests that rural people should be viewed in the context of their ‘community’. Rural people spend most of their time in their community territory. The existence of strong family and community networks is a central facet of life for them (M. Kaufman, 1997). In the context of tourism, the communities of concern are the aggregations of local people living in and around tourism zones (Joppe, 1996). In terms of administration, the community is the lowest level of the administrative hierarchy in China – the village.

Although some outside academics, in recommending a sharing in planning of decision making, assume that poor people prioritize alleviation of their powerlessness, such a priority is not usually articulated by the latter. Vernooy et al. (2003) reported that the poor rural people in Yunnan and Guizhou Provinces in China demanded diversification of their means of livelihood and improvement in their economic situation. The findings have been similar in other parts of the poor regions of China and in other less-developed countries. When landless people in Bangladesh were asked about their priorities, the answers clearly referred to activities which would generate more income (Chambers, 1983). In Zambia, the poor prioritized health, education, money and food (Chambers, 1995). It is widely agreed that poor people will probably want livelihood items such as food, clothing, shelter, work, health, education and water supply more than other higher-order satisfactions (Chambers, 1983, 1986; Doyal and Gough, 1991; Friedmann, 1992; Ghai and Alfthan, 1980; Lara and Molina, 1997). Seldom is the desire to participate in decision making articulated and, indeed, some studies even show that powerless people may feel that they should not be involved in the planning process (Timothy, 1999; Wilkes, 2000).

Another explanation for this phenomenon is that power may not be part of people’s culture (Boniface, 1999) and participation may take different forms, reflecting the social, cultural and political attributes of different localities; it may not always follow the Western paradigm of participating in the planning process (Tosun, 2000; Wall, 1995). However, the difficult question remains of how people’s basic needs are to be met if a local planning approach cannot undertake the task. Can the Western power-sharing model of participation be followed even though local people may not perceive such participation as an urgent need?

Participation: Can it Improve Poor People’s Lives?

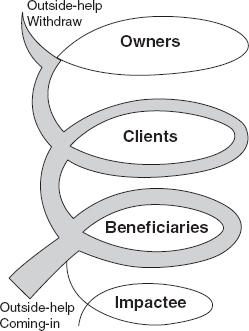

In answering this question, it is necessary to examine carefully the practicability of rural community participation in planning processes in China. There are a number of difficulties in encouraging and enabling disadvantaged groups to participate in planning and decision-making processes (PDM) (Din, 1998; Timothy, 1999; Tosun, 2000). Table 12.3 summarizes the obstacles preventing the practice of PDM in a top-down political environment, such as in China. These obstacles restrict the utility of PDM being adopted as an initial means of improving people’s lives, especially in circumstances where development is rapid and on a large scale as is commonly the case in China. In such circumstances, imposition of PDM is likely to remain little more than an academic exercise.

Table 12.3 The obstacles of practising PDM among rural poor communities in a top-down political environment

This point can be further demonstrated through the failure of the village self-management movement (SM) in China. SM attempts to provide the rural population with the opportunity to participate in the decision-making process within the village territory. However, few successful experiences have been discovered after 20 years of the SM. Yang (2003) found that the movement was sustained in only 10 per cent of the original villages and most of the villages abandoned the programme without saying so openly. The reasons for the lack of success were varied: no tangible support, such as funding, was offered by the programme and little more than lip-service was paid to the concept of ‘decentralizing decision-making power’ (G. L. Chen and Chun, 2004). Yang indicated that widespread poverty among the participants and a lack of education and awareness of democratic processes were other reasons for the failure of SM. He also suggested that the programme, at least at the initial stage, should be subsistence-related. Finally, the leaders of the villages have often been co-opted by the elite groups, especially the traditional leaders in minority groups (Yang, 2003). Bribery in village elections has been common (G. L. Chen and Chun, 2004). If the village leaders do not truly represent the people, the programme rapidly becomes meaningless.

This discussion further confirms that PDM in China may need to take a different form than is usually advocated in the West. Broader, more inclusive approaches need to be considered in order to understand and advance community participation in China. This is not a reason for questioning the fundamental utility of PDM, but rather that patience and a grounded approach are needed in practical initiatives. According to Timothy (1999), community participation in tourism development can be viewed from another perspective: participation in benefit sharing (PBS). PBS reflects an interest in finding forms of development through which benefits actually reach the majority of the population (C. M. Hall, 1994; M. Kaufman, 1997; Simmons, 1994), along with a moral requirement that a large number of people should not be systematically excluded from the benefits of development nor should they become the unwitting victims of other people’s progress (Friedmann, 1992). PBS is defined here as a process or activity through which people participate in opportunities to acquire material wealth, such as in economic activities, and in opportunities to develop human capital, such as in education, training, awareness-generation, social communication and network enhancement.

PBS, especially PBS for the poor, can contribute to development by enhancing the generation of resources, making people more productive, mobilizing local knowledge and increasing the development potential of an area (Chambers, 1983; Friedmann, 1992; M. Kaufman, 1997; Prud’homme, 1995; Reed, 2000). PBS can provide opportunities for people to help themselves instead of being helped once in a while by others through such means as subsidies (Chambers, 1987; Prud’homme, 1995; Rein, 1976). In tourism, PBS may help to sustain local cultures, craft skills and common properties, if people see these as being in their interest (Garrod and Fyall, 1998; D. R. Hall, 2000). Case studies also show that the opportunities resulting from PBS in tourism may result in subsequent investments in health, education and other social facilities (de Araujo and Bramwell, 2000) and may improve local people’s technical, communication and business skills (Bao, 2000; Bao and Chu, 1999; Gang and Kruse, 2003; Lindberg et al., 2003).

As important, PBS is practical to implement because sharing the benefits of development has long been one of the most important concepts in administrative policies in China. This can be documented with quotations from the books of many of the dynasties from as far back as the eighth century BC. After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, the Maoist approach of development was characterized by egalitarian income distribution (Kiminami, 1999). Deng Xiao Ping and Jiang Ze Min advocated that a part of the people will become rich first through development. The fourth generation of Chinese leaders called for ‘people-centred’ development in which the main task is to meet the needs of people, especially those of the rural poor. In other words, PBS should face few political constraints in its promotion. Furthermore, as shown in Table 12.4, PBS provides incentives for both decision makers and the rural people themselves to accept the concept in development. In addition, activities undertaken to share the benefits of tourism development may also benefit the tourism industry.

Successful examples of tourism-led poverty reduction that have occurred in some relatively developed rural tourism destinations in China also support the practicality of PBS in terms of both economy and literacy (Bao, 2000; Bao and Chu, 1999; Doorne et al., 2003; Gang and Kruse, 2003; Swain, 1989; Toops, 1993). Such successes, especially in previously very backward ethnic minority communities, offer hope that this can also occur in other rural places in China.

Table 12.4 Impetus and incentives for practising PBS among rural poor communities in a top-down political environment

| Perspectives | Impetus and Incentives | References |

|---|---|---|

Government |

Poverty reduction through economic and social development is high on government agenda. PBS of the rural poor allows them to be more productive and self-reliant which contribute to the whole society. PBS is consistent with the new development direction in China – ‘people-centred’ development. PBS helps to relax the existing hazard of urban-rural spillover effects of development. |

de Kadt, 1979; ESCAP, 2000; Friedmann, 1992; HDDR, 2003; Richter, 1989; Timothy, 2002 |

Tourism Industry |

PBS helps to diversify the tourist product and enrich the tourists’ experiences. Opportunities of PBS can enhance local hospitality. PBS helps to balance the costs, impacts and benefits of tourism development. |

de Kadt, 1979; Manning, 1999; Murphy, 1985; Simmons, 1994; Wall, 1997; Wilson, 1979 |

Rural Communities |

Rural people normally have the desire for material wealth and social improvement. PBS informs a better understanding about the procedures of participation because it relates to villagers’ daily life and can germinate from their own traditional and local knowledge. PBS provides the opportunities for the rural poor to get involved in tourism employment which is often accorded a relatively high status and remuneration compared with traditional options. PBS lets tourism-related small businesses, which are small in scale at the beginning, to avoid attracting the attention of outsiders to plunder the opportunities. PBS helps the rural people to acquire new skills, knowledge and experiences which make them gradually stronger through building social capital. PBS helps in the establishment of the local cooperative organizations and other mutual help social networks and enhances local awareness about participation and tourism development. PBS helps rural people to demonstrate their knowledge, creativity and intelligence, changing the negative impression of the rural poor among other stakeholder groups. This may eventually open the door of PDM to villagers. |

Burns, 1999; Cukier, 2002; Echtner, 1995; D. R. Hall, 2000; Long and Wall, 1995; Timothy, 1999; Valk, 1990; Walker, Mitchell, and Wismer, 2001 |

From this discussion, it is necessary to redefine participation to include the PBS perspective and to take the Chinese situation into consideration. Thus, participation can mean involvement in any organized activity in the development process, either to share in the benefits or to be involved in the planning or decision-making processes. PBS in development activities, based on the above definition and discussion is not only a means of gaining more financial resources, but also a process contributing to the increase of knowledge, information, a sense of self-confidence and a strengthening of social relationships.

Can PBS work as an initial intervention for encouraging the participation of rural people in tourism development to improve their lives? Some Western studies suggest that it can but this idea seems not to get the attention that it deserves in the planning field. Arai (1996) argued that empowering people economically and socially can have a great impact on the political dimensions of empowerment. Farrell (1992) and Boniface (1999) have pointed out that, through a strengthened economic position and enhanced awareness and skills, people will spontaneously and confidently demand improved access to decision making. Ghai (1989) argued that provision of economic benefits to members plays an important role in participatory initiatives: people need motivation and incentives that relate to their needs in order to generate action. As summarized in Friedmann’s (1992, p. 34) words, ‘giving full voice to the disempowered population tends to follow a certain sequence’, and the acquisition of financial and human resources may be an initial requirement for effective participation in politics. At the same time, when people get some control, such as when they are provided with the power to influence parts of the planning process, a product that is more closely related to their needs may be developed (Ghai and Alfthan, 1980). The people may become more developmentally independent (Farrell, 1992). This independence will be accompanied by a wish to be in a position to supply a much greater proportion of the required goods, resources, services and management talent which will, in turn, reinforce the PBS process.

In summary, it is suggested that PBS and PDM constitute one interrelated process through which rural people will be progressively empowered (World Bank, 1996). The separation of PBS and PDM in the above discussion is employed merely for convenience and to facilitate presentation. PBS should be initiated first to break some of the local political, social, cultural and economic constraints on participation and so that opportunities for PDM will be generated thereby. PDM will reinforce the success of PBS in the long run.

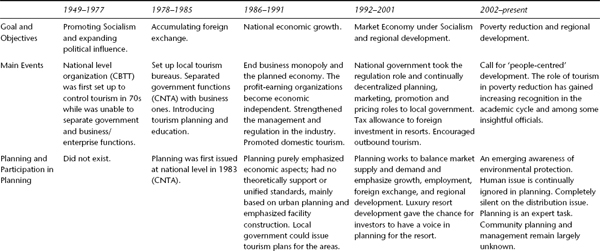

The Participatory Spiral

Participation in development, especially among disempowered populations, should be planned in stages in a top-down political situation. In the process of development, land may be expropriated and residents may be displaced. This displacement only worsens residents’ situation, and they do not share in the benefits of development. In this case, the local communities become the ‘impactees’ of development. This chain of events has occurred throughout the world (Philp and Mercer, 1999; Roville, 1988; Trask 2000; Wayakone et al., 1998). Once this problem is acknowledged and the public sector and/or the communities themselves have the desire to change the situation, the poor may firstly be introduced into the development process as ‘beneficiaries’ – recipients of services, resources, training, information and development interventions (World Bank, 1996). As the capacity of the poor is strengthened and their voices begin to be heard, they become ‘clients’ who are capable of demanding and paying for goods and services provided by government and the private development sectors (ibid.). Active participation in decision-making and planning processes can then be initiated among the previously poor people (Rein, 1976). Although the voices of such people at this stage may not yet have an influence equal to those who have more power politically (Abers, 1998), they have essentially become partners in development, and not merely another resource or problem that must be dealt with (Farrell, 1992). With investment power, these people may have the confidence and resources to ask to be better ‘heard’ in initiating development activities. When these people further strengthen their capacity, they may ultimately become ‘owners’ and managers of the development activities. Previously poor people will then have obtained the highest level of participation (Boniface, 1999; World Bank, 1996). It is not the authors’ intention to suggest that the villagers will eventually own the hotels. Rather, if means can be found to facilitate movement up the spiral, ‘ownership’ will occur in the sense that local people will have greater control over the decisions that impinge upon their lives and will benefit substantially from the developments that occur on their territory. However, local communities, especially the majority of the rural poor, rarely act spontaneously (Din, 1998; Friedmann, 1992) because they lack innovative leadership, adequate financial, material, and technical means, and training (ESCAP, 2000). They may be unable to take advantage of the opportunities and resources that are available at the beginning stage of the development process. Just as pupils require a teacher, the poor need outsiders to take initiatives in this regard and to work with them (Abers, 1998). Therefore, as part of the process, the progress of participation involves consultation or collaboration with diverse individuals and groups outside of the disempowered communities (Ristock and Pennell, 1996). However, empowerment is not a process of treating the poor as ‘objects’ or ‘target groups’; genuine and lasting participation must be a process undertaken for oneself (Friedmann, 1992; Lather, 1991). Based on the above discussion, the participatory spiral model is formulated in Figure 12.1.

This model demonstrates that encouraging rural community participation should start with PBS and proceed to PDM in development. Local people initially have no share of the tourism-generated benefits, then progress through participation in benefit-generation activities to gain resources, knowledge, information, confidence, etc., to the control of the development initiatives and to being in charge of the planning and decision-making processes. Increased effort, along with achievements and progress in economic, social and political dimensions, which reinforce each other, moves the community through the participatory levels in the model. The role of the rural community in the development process may switch from the initial role of impactee, to beneficiary, to client and ultimately to owner. Moreover, the model adopts the concepts of ‘outsiders’ entry phase’ and ‘withdrawal phase’ to show that outside help is necessary at first. Then, outside influence is gradually reduced and eventually withdrawn when the local people are capable of carrying on alone. This model also accords with the notion that human needs evolve in sequence; human needs are presented not in a static manner, but as changing over time in line with the growth of the economy and the aspirations of people (Doyal and Gough, 1991; Ghai, 1980; M. Kaufman, 1997; Taylor, 1998).

Figure 12.1 Spiral of rural community participation in development

With respect to tourism development, one might ask:

Secondly, relating to tourism development:

These questions constitute some of the key topics that are being addressed in studies in Hainan based on two primary research approaches:

Shared planning and decision making among various stakeholder groups is a major concept in the prevailing Western approaches to tourism planning (C. M. Hall, 2000a), although the extent of participation, the influences of the participants and the groups involved are variable. Moreover, shared decision making and planning have been viewed as being a means to pursue a more equitable tourism development and to balance the distribution of tourism-led benefits among various stakeholder groups. However, participation is an issue that extends beyond the techniques that are available to planners to facilitate public input; it reflects power relationships, cultural and democratic values, structures of public governance, and institutional arrangements at a destination. In the West, some of these determinant factors may be at least partially conducive to the creation of an environment in which shared planning and decision-making processes can be implemented.

In contrast, the current tourism planning approach in China is heavily focused on economic dimensions and it tends to be isolated from broader development perspectives. It emphasizes tourism market supply and demand and focuses almost entirely on designing and promoting the main components of tourism such as attractions, accommodation, transportation and tours. The planning emphasis, in the terminology of Burns (1999) is ‘tourism first’, a perspective that concentrates on developing tourism: locating suitable sites for the development of resorts, hotels and other tourist attractions to fulfil the tourists’ demands. Although an awareness of sustainability is growing, and tourism planning in China has begun to incorporate the ideas of protecting natural resources and using them carefully, such planning remains silent on distributional issues and on the use of tourism as a means of social development. Moreover, community participation in the planning process continues to be largely unknown in China. As shown in Table 12.3, the external environment is not conducive to the implementation of a Western-style participatory planning process.

In spite of this situation, with the deteriorating situations of rural poverty in some poor regions of China and increasing polarization between urban and rural areas generally, there is a growing demand for poverty reduction through tourism development. As many insightful people in China have pointed out, failing to involve the rural poor in a more productive development process will not only hamper further economic and social development in China, but will also call into question the stability of the society (Q. L. Chen, 2002; Dong, 2002; HDDR, 2003; Xiao, 2001). Therefore, there is an urgent need to incorporate people into the development process to improve their lives and secure their futures. This is in the interest of the people themselves as well as the broader collective.

However, the Western style of shared planning and decision making is not viable as an initial means to facilitate the participation of rural communities in China where tradition prescribes a top-down political process. An approach is needed that is grounded in practical initiatives. Participation in tourism development to share in its benefits (PBS) is practical in China because it faces fewer obstacles from political, social, cultural and economic perspectives when compared with the practice of shared decision making (PDM), particularly at this stage. Based partly on World Bank proposals, a participatory spiral model has been proposed that suggests that PBS should precede PDM, particularly among the rural poor in a top-down planning context. As shown in the spiral model, people start with having no share of the tourism-generated benefits, then progress through participation in benefit-generation activities to eventually assume greater control over development initiatives and to take charge of the planning and decision-making processes. Because poor people rarely act spontaneously, it is necessary that they obtain some outside support along the way. Planners mitigate the ‘unavoidable side-effects’ of tourism and other forms of development that often accrue unfairly to poor people ‘in the way’ of ‘progress’ by doing their best to facilitate their sharing in the benefits of tourism development to the best of their abilities. We are currently exploring, through case studies in Hainan, how community participation might be facilitated in what is currently a top-down political and planning environment, and how PBS and PDM can be initiated and may evolve in such settings. As intermediaries in this process, we will gather and report the situations, desires, concerns and efforts of local community members in places that are in the early stages of tourism development and transfer this information to government officials. Through this indirect communication process, it is hoped that improved policies, plans and planning processes will result, that local benefits will be enhanced, and a greater level of local involvement in tourism development may gradually emerge.

Abers, R. (1998) ‘From clientelism to cooperation: Local government, participatory policy and civic organizing in Porto Alegre, Brazil’. Politics and Society, 26(4), 511–38

Alipour, H. (1996) ‘Tourism development within planning paradigms: The case of Turkey’. Tourism Management, 17(5), 367–77

Arai, S. M. (1996) ‘Benefits of citizen participation in a healthy communities initiative: Linking community development and empowerment’. Journal of Applied Recreation Research, 21(1), 25–44

de Araujo, L. M. and Bramwell, B. (2000) ‘Stakeholder assessment and collaborative tourism planning: The case of Brazil’s Costa Dourada Project’. In B. Bramwell and B. Lane (eds) Tourism collaboration and partnerships: Politics, practice and sustainability. Clevedon: Channel View Publications, pp. 272–94

Bahaire, T. and Elliott-White, M. (1999) ‘Community participation in tourism planning and development in the historic city of York, England’. Current Issues of Tourism, 2(2/3), 243–76

Baidal, J. A. I. (2004) ‘Tourism planning in Spain: Evolution and perspectives’. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(2), 313–33

Bao, J. G. (2000) The investigation of tourism development. Beijing: Science Press

Bao, J. G. and Chu, Y. F. (1999) Tourism geography (Rev. edn). Beijing: Higher Education Press

Boniface, P. (1999) ‘Tourism and cultures: Consensus in the making?’. In M. Robinson and P. Boniface (eds) Tourism and cultural conflicts. Oxford: CABI Publishing, pp. 287–306

Bramwell, B. and Lane, B. (1993) ‘Sustainable tourism: An evolving global approach’. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1(1), 1–5

Bramwell, B. and Sharman, A. (1999) ‘Collaboration in local tourism policymaking’. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(2), 392–415

Burns, P. (1999) ‘Paradoxes in planning: Tourism elitism or brutalism?’. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(2), 329–48

Cai, S. K. (1999) Self-reflection after Hainan’s ten-year development’. Hong Kong: Sanlian Bookstore (Hong Kong) Ltd

Campbell, S. and Fainstein, S. S. (1996) ‘Introduction: The structure and debates of planning theory’. In S. Campbell and S. S. Fainstein (eds) Readings in planning theory. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers, pp. 1–18

Chambers, R. (1983) Rural development: Putting the last first. New York: Longman

Chambers, R. (1986) Sustainable livelihood thinking: An approach to poverty, environment and development. London: The International Institute for Environment and Development

Chambers, R. (1987) Sustainable rural livelihoods: A strategy for people, environment and development: An overview for ONLY ONE EARTH, Conference on Sustainable Development. London: The International Institute for Environment and Development

Chambers, R. (1995) Poverty and livelihoods: Whose reality counts? (Discussion Paper No. 347). Brighton: Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex

Chen, Q. L. (2002) The discussion of Chinese peasants’ diathesis. Beijing: Contemporary World Publishing Company

Chen, G. L. and Chun, T. (2004) The investigation of rural Chinese. Beijing: The People’s Literature Publishing

Conyers, D. and Hills, P. J. (1984) An introduction to development planning in the Third World. New York: John Wiley and Sons

Costa, C. (2001) ‘An emerging tourism planning paradigm? A comparative analysis between town and tourism planning’. International Journal of Tourism Research, 3(6), 425–41

Cuthbertson, I. D. (1983) ‘Evaluating public participation: An approach for government practitioners’. In G. A. Daneke, M. W. Garcia and J. D. Priscoli (eds) Public involvement and social impact assessment, Boulder, CO: Westview Press, pp. 101–9

Davidoff P. (1965) ‘Advocacy and pluralism in planning’. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 31(4), 331–8

Davidoff P. (1975) ‘Working towards redistributive justice’. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 41(5), 317–18

Din, K. H. (1998) ‘Tourism development: Still in search of a more equitable mode of local involvement’. In C. Cooper and S. Wanhill (eds) Tourism development: Environmental and community issues. New York: John Wiley and Sons, pp. 153–62

Dong, H. (2002) The investigation of Hainan national farms. Hainan: The People’s Government of Hainan Province

Doorne, S., Ateljevic, I. and Bai, Z. (2003) Representing identities through tourism: Encounters of ethnic minorities in Dali, Yunnan Province, People’s Republic of China’. International Journal of Tourism Research, 5(1), 1–11

Doyal, L. and Gough, I. (1991) A theory of human need. Basingstoke: Macmillan

ESCAP (2000) The empowerment of the rural poor through decentralization in poverty alleviation actions. Bangkok: Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific

Evans, G. (2000) ‘Planning for urban tourism: A critique of borough development plans and tourism policy in London’. International Journal of Tourism Research, 2(5), 307–26

Farrell, B. (1992) ‘Tourism as an element in sustainable development: Hana, Maui’. In V. L. Smith and W. R. Eadington (eds) Tourism alternatives: Potentials and problems in the development of tourism. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 115–32

Fletcher, J. and Cooper, C. (1996) ‘Tourism strategy planning: Szolnok County, Hungary’. Annals of Tourism Research, 23(1), 181–200

Friedmann, J. (1992) Empowerment: The politics of alternative development. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell

Gang, X. and Kruse, C. (2003) ‘Economic impact of tourism in China’. In A. A. Lew, L. Yu, J. Ap and G. Zhang (eds) Tourism in China. New York: Haworth Hospitality Press, pp. 83–102

Garrod, B. and Fyall, A. (1998) ‘Beyond the rhetoric of sustainable tourism?’. Tourism Management, 19(3), 199–212

Gauteng Tourism Authority (2003) ‘Responsible tourism planning framework’. Retrieved 15 November 2011, from http://fama2.us.es:8080/turismo/turismonet1/economia%20del%20turismo/turismo%20responsable/responsible%20tourism%20report.pdf

Getz, D. (1986) ‘Models in tourism planning: Towards integration of theory and practice’. Tourism Management, 7(1), 21–32

Getz, D. (1987) ‘Tourism planning and research: Traditions, models and futures’. Paper presented at the Australian Travel Research Workshop, Bunbury, Western Australia, November

Ghai, D. P. (1980) ‘What is the basic needs approach to development all about?’. In D. P. Ghai, A. R. Khan, E. L. H. Lee and T. Alfthan (eds) The basic-needs approach to development: Some issues regarding concepts and methodology. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labor Office, pp. 1–18

Ghai, D. P. (1989) ‘Participatory development: Some perspectives from grassroots experiences’. Journal of Development Planning, 19, 215–46

Ghai, D. P. and Alfthan, T. (1980) ‘What is the basic needs approach to development all about?’. In D. P. Ghai, A. R. Khan, E. L. H. Lee and T. Alfthan (eds) The basic-needs approach to development: Some issues regarding concepts and methodology. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labor Office, pp. 19–59

Gill, A. M. (1997) ‘Competition and the resort community: Towards an understanding of residents’ needs’. In P. E. Murphy (ed.) Quality management in urban tourism. New York: John Wiley and Sons, pp. 55–66

Grant, J. (1989) ‘From “human values” to “human resources”: Planners’ perceptions of public role and public interest’. Plan Canada, 29, 11–18

Gunn, C. A. (1988) Tourism planning (2nd edn). New York: Taylor and Francis

Hall, C. M. (1994) Tourism and politics: Policy, power and place. New York: John Wiley and Sons

Hall, C. M. (2000a) Tourism planning: Policies, processes and relationships. Harlow: Prentice Hall

Hall, C. M. (2000b) ‘Rethinking collaboration and partnership: A public policy perspective’. In B. Bramwell and B. Lane (eds) Tourism collaboration and partnerships: Politics, practice and sustainability. Clevedon: Channel View Publications, pp. 143–58

Hall, D. R. (2000) ‘Tourism as sustainable development? The Albanian experience of “transition”’. International Journal of Tourism Research, 2(1), 31–46

Hall, P. G. (1980) Great planning disasters. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson

Han, J. (2004) China: From the urban-rural dual to harmonious development. Beijing: People’s Publishing House

Haywood, K. M. (1988) ‘Responsible and responsive tourism planning in the community’. Tourism Management, 9(2), 105–18

HDDR (2003) Centering the people in the development: Establish and practice the scientific development. Hainan: Department of Reformation and Development of Hainan Province

Healey, P. (1992) ‘Planning through debate: The communicative turn in planning theory’. Town Planning Review, 63(2), 143–62

Hong, S.-K., Kim, S.-I. and Kim, J.-H. (2003) ‘Implications of potential green tourism development’. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(2), 323–41

Inskeep, E. (1991) Tourism planning: An integrated and sustainable development approach. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold

Jamal, T. B. and Getz, D. (1995) ‘Collaboration theory and community tourism planning’. Annals of Tourism Research, 22(1), 186–204

Jamal, T. B. and Getz, D. (1997) ‘“Visioning” for sustainable tourism development: Community-based collaborations’. In P. E. Murphy (ed.) Quality management in urban tourism. New York: John Wiley and Sons, pp. 199–220

Joppe, M. (1996) ‘Sustainable community tourism development revisited’. Tourism Management, 17(7), 475–79

de Kadt, E. J. (1979) Tourism: Passport to development? Perspectives on the social and cultural effects of tourism in developing countries. New York: Oxford University Press

Kaufman, J. L. and Jacobs, H. M. (1987) ‘A public planning perspective on strategic planning’. Journal of the American Planning Association, 53(1), 23–33

Kaufman, M. (1997) ‘Community power, grassroots democracy and the transformation of social life’. In M. Kaufman and H. D. Alfonso (eds) Community power and grassroots democracy: The transformation of social life. London: Zed Books, pp. 1–26

Keogh, B. (1990) ‘Public participation in community tourism planning’. Annals of Tourism Research, 17(3), 449–65

Kiminami, L. (1999) The basic analysis on poverty problem in China (FASID-IDIRI Occasional Paper Series). Tokyo: Foundation for Advanced Studies in International Development, International Development Research Institute

Klosterman, R. E. (1996) ‘Arguments for and against planning’. In S. Campbell and S. S. Fainstein (eds) Readings in planning theory. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers, pp. 150–68

Lanfant, M.-F. and Graburn, N. H. H. (1992) ‘International tourism reconsidered: The principle of the alternative’. In V. L. Smith and W. R. Eadington (eds) Tourism alternatives: Potentials and problems in the development of tourism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 88–112

Lara, S. and Molina, E. (1997) ‘Participation and popular democracy in the committees for the struggle for housing in Costa Rica’. In M. Kaufman and H. D. Alfonso (eds) Community power and grassroots democracy: The transformation of social life, London: Zed Books, pp. 27–54

Lather, P. A. (1991) Getting smart: Feminist research and pedagogy with/in the postmodern. New York: Routledge

Lau, M. (2003) ‘Coastal zone management in the People’s Republic of China: An assessment of structural impacts on decision making processes’ (Working Paper No. FNU-28). Retrieved 15 November 2011, from Research Unit Sustainability and Global Change, University of Hamburg: http://econpapers.repec.org/paper/sgcwpaper/40.htm

Lickorish, L. J. and Jenkins, C. L. (1997) An introduction to tourism. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann

Lindberg, K., Tisdell, C. and Xue, D. (2003) ‘Ecotourism in China’s nature reserves’. In A. A. Lew, L. Yu, J. Ap and G. Zhang (eds) Tourism in China, New York: Haworth Hospitality Press, pp. 103–25

Lindblom, C. E. (1959) ‘The science of “muddling through”’. Public Administration Review, 19(2), 79–88

Long, V. and Wall, G. (1996) ‘Successful tourism in Nusa Lembongan, Indonesia?’. Tourism Management, 17(1), 43–50

Martopo, S. and Mitchell, B. (Eds.) (1995) Bali: Balancing environment, economy and culture (Department of Geography Publication Series No. 44). Waterloo, Canada: University of Waterloo

Murphy, P. E. (1983) ‘Tourism as a community industry: An ecological model of tourism development’. Tourism Management, 4(3), 180–93

Murphy, P. E. (1985) Tourism: A community approach. New York: Methuen

Murphy, P. E. (1988) ‘Community driven tourism planning’. Tourism Management, 9(2), 96–104

Murphy, P. E. (1992) ‘Data gathering for community-oriented tourism planning: Case study of Vancouver Island, British Columbia’. Leisure Studies, 11(1), 65–79

Page, S. (1995) Urban tourism. London: Routledge

Philp, J. and Mercer, D. (1999) ‘Commodification of Buddhism in contemporary Burma’. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(1), 21–54

Pretty, J. (1995) ‘The many interpretations of participation’. Focus, 16(1), 4–5

Prud’homme, R. (1995) ‘The dangers of decentralization’. World Bank Research Observer, 10(2), 201–20

Reed, M. G. (2000) ‘Collaborative tourism planning as adaptive experiments in emergent tourism settings’. In B. Bramwell and B. Lane (eds) Tourism collaboration and partnerships: Politics, practice and sustainability. Clevedon: Channel View Publications, pp. 247–71

Rein, M. (1976) Social science and public policy. Harmondsworth: Penguin

Richter, L. K. (1983) ‘Political implications of Chinese tourism policy’. Annals of Tourism Research, 10(3), 395–413

Ristock, J. L. and Pennell, J. (1996) Community research as empowerment: Feminist links, postmodern interruptions. Toronto, Canada: Oxford University Press

Roville, G. (1988) ‘Ethnic minorities and the development of tourism in the valleys of North Pakistan’. In P. Rossel (ed.) Tourism: Manufacturing the exotic. Copenhagen: International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs, pp. 147–76

Roy, J. (1998) Mechanisms for public participation in economic decision-making. September. Ottawa: Task Force on the Future of the Canadian Financial Services Sector

Sheldon, P. J. and Abenoja, T. (2001) ‘Resident attitudes in a mature destination: The case of Waikiki’. Tourism Management, 22(5), 435–43

Simmons, D. G. (1994) ‘Community participation in tourism planning’. Tourism Management. 15(2), 98–108

Sofield, T. H. B. and Li, F. M. S. (1998) ‘Tourism development and cultural policies in China’. Annals of Tourism Research, 25(2), 362–92

Swain, M. B. (1989) ‘Developing ethnic tourism in Yunnan: Shilin Sani’. Tourism Recreation Research, 14(1), 33–39

Taylor, N. (1998) ‘Mistaken interests and the discourse model of planning’. Journal of the American Planning Association, 64(1), 64–75

Timothy, D. J. (1998) ‘Cooperative tourism planning in a developing destination’. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 6(1), 52–68

Timothy, D. J. (1999) ‘Participatory planning: A view of tourism in Indonesia’. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(2), 371–91

Tisdell, C. and Wen, J. (1991) ‘Foreign tourism as an element in PR China’s economic development strategy’. Tourism Management, 12(1), 55–67

Toops, S. (1993) ‘Xinjiang’s handicraft industry’. Annals of Tourism Research, 20(1), 88–106

Tosun, C. (2000) ‘Limits to community participation in the tourism development process in developing countries’. Tourism Management, 21(6), 613–33

Tosun, C. and Jenkins, C. L. (1996) ‘Regional planning approaches to tourism development: The case of Turkey’. Tourism Management, 17(7), 519–31

Tosun, C. and Jenkins, C. L. (1998) ‘The evolution of tourism planning in Third-World Countries: A critique’. Progress in Tourism and Hospitality Research, 4(2), 101–14

Trask, H.-K. (2000) ‘Native social capital: The case of Hawaiian sovereignty and Ka Lahui Hawaii’. Policy Sciences, 33(3/4), 375–85

Travis, A. S. (ed.) (2011) Planningfor Tourism, Leisure and Sustainability: International Case Studies. Wallingford: CABI

Vernooy, R., Sun, Q. and Xu, J. C. (2003) Voices for change: Participatory monitoring and evaluation in China. Ottawa, Canada: International Development Research Centre

Wahab, S. and Pigram, J. J. (1997) ‘Tourism and sustainability: Policy considerations’. In S. Wahab and J. J. Pigram (eds) Tourism development and growth: The challenge of sustainability. London: Routledge, pp. 277–90

Wall, G. (1995) ‘People outside the plans’. In W. Nuryanti (ed.) Tourism and culture: Global civilization in change? Yogyakarta, Indonesia: Gadjah Mada University Press, pp. 130–37

Wall, G. (1996) ‘One name, two destinations: Planned and unplanned coastal resorts in Indonesia’. In L. C. Harrison and W. Husbands (eds) Practicing responsible tourism: International case studies in tourism planning, policy and development. New York: John Wiley and Sons, pp. 41–57

Wall, G. (1997) ‘Linking heritage and tourism in an Asian City: The case of Yogyakarta, Indonesia’. In P. E. Murphy (ed.) Quality management in urban tourism. New York: John Wiley and Sons, pp. 139–48

Wall, G. and Long, V. (1996) ‘Balinese homestays: An indigenous response to tourism opportunities’. In R. Butler and T. Hinch (eds) Tourism and indigenous peoples. London: International Thomson Business Press, pp. 27–48

Wayakone, S., Shuib, A. and Mansor, W. W. (1998) ‘Residents’ attitude towards tourism development in Dong Hua Sao Protected Area, Laos’. Malaysian Journal of Agricultural Economics, 12, 16–32

Weaver, D. B. (1995) ‘Alternative tourism in Montserrat’. Tourism Management, 16(8), 593–604

Wilkes, A. (2000) ‘The functions of participation in a village-based health pre-payment scheme: What can participation actually do?’. IDS Bulletin, 31(1), 31–6

Willis, K. (1995) ‘Imposed structures and contested meanings: Policies and politics of public participation’. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 30(2), 211–27

World Bank (1996) The World Bank participation sourcebook. Washington, DC: World Bank

Xiao, Y. (2001) ‘How difficult to be a peasant in this modern society?’. In CEAR (China Economy Annual Report) (ed.) Resuscitation: The problems of Chinese peasants. Lanchow: Lanchow University Press, pp. 117–20

Yang, Y. C. (2003) Investigating the problems of self management in Chinese villages. Shanghai: Fu Dan University Press

Yeh, A. G. and Wu, F. (1999) ‘The transformation of the urban planning system in China from a centrally planned to transitional economy’. Progress in Planning, 51(3), 167–252

Zhang, G. R. (2003) ‘Tourism research in China’. In A. A. Lew, L. Yu, J. Ap and G. Zhang (eds) Tourism in China. New York: Haworth Hospitality Press, pp. 67–82

Zhang, T. (2002) ‘Challenges facing Chinese planners in transitional China’. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 22(1), 64–76

Zhang, W. (2003) ‘Measuring stakeholder preparedness for tourism planning in Leshan, China’ (UMP-Asia Occasional Paper No. 57). Retrieved 15 November 2011, from http://fama2.us.es:8080/turismo/turismonet1/economia%20del%20turismo/turismo%20zonal/lejano%20oriente/measuring%20stakeholder%20tourism%20planning%20in%20China.pdf