Resorts have been a feature of travel and tourism for a long time. Their origins can be traced back to Roman times when the concept spread throughout Europe in the wake of their conquering legions. From the simple origins of public baths and restorative mineral springs their typical structure became ‘an atrium surrounded by recreational and sporting amenities, restaurants, rooms, and shops’ (Mill, 2001, p. 4), a description that still describes many modern resorts.

Since those early days of resort development the popularity of this element of tourism has waxed and waned; but it has survived the changing times by adjusting its early model to suit new tastes and conditions, to become a new force in today’s relatively stable and prosperous times. Early on, the original health purpose of resorts was supplemented and eventually overtaken by social and political motivations, as exemplified by the resurrection of the hot springs at Bath, England, which became an important part of the English royal court circuit. This pattern was followed in the ‘New World’ by the railways, using hot springs resorts in the wilderness national parks to draw the wealthy and privileged westward, as in the case of Canadian Pacific’s Banff Springs Hotel in Alberta, Canada. Today similar grand and enticing resort concepts are being developed throughout the hinterlands of Europe, helping to lure the wealthy and influential to new areas of potential economic and social development. An example of this is in the Gulf States, where several major luxury integrated resort complexes have been built or are under construction to provide another face to these Muslim states and to assist them in diversifying their economies. An example of this trend is the US$2.9 billion Emirates Palace in Abu Dhabi, which:

Although it has fewer than 400 rooms, the hotel features 128 kitchens and pantries, 1002 custom-made Swarovski crystal chandeliers…a layout so sprawling staff will soon be equipped with golf carts to navigate the corridors, ‘some of them… over a kilometre long’… room prices range from a modest US$608 a night to US$12,608 (subject to a 20 per cent service charge).

(Pohl, 2005, p. 12)

It is not only the wealthy who now enjoy the benefits of resorts, for the growth of industry and commerce has brought such delights within the reach of the masses. They have either followed the past elite to their secluded ‘hide-away’ resort retreats as exemplified by the development of Brighton around the Prince of Wales’s Brighton Pavilion; or they have stimulated the building of their own style of mass resort, as in the case of seaside resorts such as Australia’s Gold Coast or gambling resorts such as Las Vegas, and even combining the two interests in Atlantic City. Furthermore, resorts for the working class have been developed in various forms, ranging from camps to chalets and dormitories as exemplified by the Butlins camps and the Roompot parks in The Netherlands.

Despite this track record of successful adjustment and mutation over the centuries the study of this particular phenomenon has generated only a modest level of interest among tourism academics – even in this era of supposed attention to sustainability. Evidence of this situation and possible reasons for it may be found in a tabulation of recent articles linked to resorts in the three leading tourism journals over the past five years.

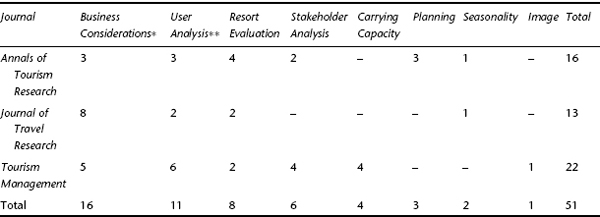

A review of articles that were related in any way to resorts, either stated or inferred, was compiled from the period 2000 to 2004 (Table 21.1). It revealed a total of 53 references, which consisted of either full articles or short research notes. The journal that had the most extensive coverage of resort-related articles was Tourism Management, which recorded 45 percent of the noted articles. This journal’s management focus was evident in its emphasis on business- and user-related topics, plus its contribution in all the other identified categories. The Annals of Tourism Research was the second major source with 30 percent of the identified articles and these articles revealed its social science perspective, with the highest number of papers relating to the evolutionary model and its concerns with general planning issues. In comparison to the first two, the Journal of Travel Research revealed its Business School roots, with the strongest focus on ‘business considerations’. The different foci of the three journals along with the extensive range of topics, even when some have been collapsed into a generic format, reveal the extensive nature of resort activities and their impacts which make them relevant to a variety of domains and research questions. As such, there is a broad interface between the issues found in resort domains and those examined in other areas of tourism research; but some feel resorts deserve to be studied in their own right because they are an identifiable subset of the tourism market with their own needs and issues.

Table 21.1 Resort-related articles in key journals 2000–2004

* Business Considerations include – competitiveness, benchmarking, yield management, satisfaction, value, loyalty, and service quality topics.

** User Analysis includes – gambling, skiers, cruise ship passengers, golf and retirees.

Included amongst those who feel resorts should be examined on their own merits are Inskeep, Gee and Mill, each of whom makes a case for paying special attention to resorts due to some distinctive differentiating factors. Inskeep (1991) states that particularly well-designed resorts can become attractions in themselves and he devotes a chapter to ‘planning tourist resorts’ under the umbrella of community tourism. Within this framework he emphasizes two factors:

Gee (1996) considers resorts differ from other sorts of tourism destination in that:

Mill (2001) considers resorts have a combination of elements that make them distinctive. These are:

Within these descriptors of resorts and their management needs certain commonalities can be identified. Resorts are distinctive in that they:

Such descriptions of the resort structure and approach are considered sufficient by some to distinguish resort management from other forms of management within tourism, but how does their situation relate to theoretical developments and what are resorts’ current and future management issues and directions? These are questions that this chapter intends to address and answer within the context of this conference.

If one is going to study a phenomenon such as resorts, with a goal to assessing their links to theory and to providing useful management information, one appropriate avenue of research is to use the analytical approach of scientific inquiry (Berry and Marble, 1968; Pojman, 2003). This involves a three-step process:

At this point most students of resort management would claim we are at the explanation stage, seeking to understand the internal and external forces that are moulding current resort patterns.

If we apply some of the better known social science and business theories to the scientific enquiry of resorts we can see a productive theoretical and management symbiosis emerging.

Describe and Classify

In terms of step one there has been considerable attention paid to describing the wide range of resorts and attempting to define them. Those who have attempted to classify resorts include Pearce (1989), Krippendorf (1987), Ayala (1991), Gee (1996) and Prideaux (2000). Within these varied descriptions of resorts several consistencies emerge that help to distinguish resorts from other forms of tourism. First, there is confirmation of the business focus of resorts in the vast majority of the definitions. Second, the business focus is one that emphasizes capturing and holding guests. Third, an important part of that business process is to satisfy guest expectations with outstanding facilities and service. Fourth, the scale of resorts can vary from an individual establishment to an urban destination.

All of these dimensions can be seen in the current resort development in Dubai, where resorts are being erected to help diversify the local economy and attract more air passengers to use Dubai as a stop-over or destination.

For Dubai, that day (when the oil runs out) is only about ten years away. It has already developed its economy to the point where oil accounts for just 7 percent of GDP…Dubai has made a series of huge investments… Along the coast are luxury (resort) hotels, the Wild Wadi Water Park, new (artificial) offshore islands (resort complexes)…Already more than 5 million tourists arrive every year, a number that could easily double with the opening of new attractions (such as Burg Al Arab resort hotel and the Ski Dubai indoor ski resort).

(Economist, 2006, p. 56)

The principal theoretical contribution to the classification system of step one is Butler’s ‘Tourism Area Life Cycle’ (Butler, 2006). Although this model has been criticized for not being an explanatory theory it has proven to be sufficiently robust as a descriptive theory, accurately portraying the general evolution of a wide variety of resort and tourist destinations around the world. This is because the Tourism Area Life Cycle is based on two explanatory theories, the family life cycle which helps to explain the evolving demand patterns of consumers for tourist destinations and the product life cycle which helps to explain supply side adjustments to evolving markets. These provide the underpinnings to what has proved to be a regular six-point evolutionary process for tourist destinations: exploration, involvement, development, consolidation, stagnation, decline or rejuvenation. As in the case of all social science and management theory there are some exceptions to this pattern, where resorts for example are planned centrally and superimposed on a community, as in the case of Cancun, but the general pattern has occurred so frequently it has become accepted by resort management as an important framework to their decision making. There is a constant referral to keeping ‘on top of the wave’ of the S curve in the TALC theory.

Explain

To move to step two we need to understand what we have classified in step one, and the TALC theory is a classic example of this necessity. One of the early criticisms of Butler’s model was the lack of explanation concerning why destinations moved from stage to stage, and the consequent difficulty in identifying the causes and timing of these significant events within the model (Haywood, 2006). Two theories which can help to explain the TALC’s evolutionary curve for resorts are the Family Life Cycle and Product Life Cycle theories, plus the ecological model of community tourism.

The Family Life Cycle reflects the changing socio-economic circumstances that can be expected within a household over the life of its founders (Carter and McGoldrick, 2005):

While the Family Life Cycle was first mooted in the era of stable nuclear families, many of its socio-economic principles can still be applied to the greater variety of households that exist today. The impact of a home purchase is dramatic on any form of household and still reduces spending in other areas, unless the household is extremely fortunate. The popularity of travel for the young and seniors is still strong, as these groups represent significant market segments for tourism in general and resorts in particular. The seniors market will be used later in this chapter to demonstrate its growing importance to resort development and management.

The Product Life Cycle proposed that most products go through various stages of development and production. Many new products are introduced to the market each year, and most of them are variations on existing themes like a new car model. The important second stage is the trial period for the new product, when opinion leaders try it out and make their personal recommendations. If all goes well the third stage is the adoption phase. It is at this juncture when the public at large decides to follow the recommendations of the opinion leaders and purchases the product in volume. This is the stage at which the product can be classified as a success and the company reaps the rewards of its research, development and marketing costs. The fourth stage is a saturation of the market, meaning in some cases one sale or experience is enough for most people (a movie or bungee jump) or in other cases the purchase satisfies for many years (a house or university degree). Stage five represents a decline in production levels, as the market now depends on replacement or the arrival of new consumers via new household creations or international markets to create demand (like cigarettes).

The parallels between the Product Life Cycle and TALC are obvious and have been acknowledged by Butler. The relevance to resorts as a specific leisure product is particularly germane because few resorts are unique in terms of what they provide, they are simply variations on existing themes such as snow resorts or beach resorts. Thus, when they are introduced into the growing crowded market they need to be noticed and they need to be tried. In this regard many resorts attempt to lure celebrities and events so the opinion leaders will visit and be seen trying out this new product. But the key will be whether the targeted market segments will adopt this new product and make repeat visits or recommendations to others. Even if a resort succeeds in reaching the success of stage four it must prepare against stage five and its forecast of decline. Some resorts prepare for this by reinventing themselves, with new attractions, others decide to age with their clientele and become mature resorts catering primarily for a certain lifestyle. Throughout both the Family Life Cycle and Product Life Cycle resorts will need to balance their offerings and look to the future if they are to be ready for it.

The question of balance and looking to the future are key elements of the ecological model proposed by Murphy (1985) in his community tourism approach. He has demonstrated the link between destination stakeholders and the general principles of ecological equilibrium, emphasizing the need for balance between such forces as economic return, social vitality, environmental sustainability and the general quality of life for tourism and its host communities. In terms of resorts this explains the need for both internal and external management processes and emphasizes the need to work with the local community and environmental setting, in order to achieve the best outcomes for as wide a range of stakeholders as possible.

Predict and Forecast

Murphy’s ecological model for community tourism is an early attempt to explain the mutual benefits of sustainable development, a theory that has received increased attention as a means to predict future outcomes of current management techniques. Murphy and Price (2005) have identified 15 themes to the modern concept of sustainable development that include social, environmental and political considerations in addition to economic and development concerns, but all these themes reflect an attempt to balance economic goals with social and environmental goals. Sustainable development theories attempt to demonstrate the benefits of a systems approach to tourism development and planning, but they have proved to be difficult to implement and test.

Two techniques that could help in the area of testing and refining the sustainable development theory are stakeholder analysis and triple bottom line auditing. Stakeholder analysis attempts to identify the principal actors and impact groups in any development, and by focusing on their needs and priorities helps to concentrate on potential collaborative strategies (Murphy and Murphy, 2004). The triple bottom line audit is one way to examine how well a development is meeting its economic, social and environmental goals. By offering a simplified audit process and structure Elkington (1999, p. 93) suggests the triple bottom line approach can provide ‘new sustainability indicators’ that can measure and guide our progress in this direction.

Examples of some of these theories and techniques are being applied within resorts, most notably within the growing number of eco-resorts such as Kingfisher Bay resort on Fraser Island, the largest sand island in the world and a designated World Heritage site. This resort has designed a facility that has minimum impact on the environment and focuses on teaching visitors about that environment and their place within it. Besides the expected guided tours the resort has put ‘on show’ its waste treatment plant. This reminds visitors they have an inevitable impact, but with careful treatment human waste can become benign, and can even be turned into a recycling revenue source when the resort ships its bags of fertilizer back to the mainland.

To provide the infrastructure and resources to operate as a sustainable business resorts must first succeed in winning customers, and the theory many have found helpful in this regard is Porter’s theory on competitive advantage. Porter has written several books on various aspects of this theory over the years (Porter, 1980, 1990, 1998), but the crux of his thinking is that to compete in today’s global market a business must differentiate itself and control costs in terms of its selected target markets. For resorts this means selecting a market segment or segments they feel they can satisfy, then to present a product that will be noticeable to that segment in the crowded marketplace; in the process they need to ensure they are offering value for money. This means that a business developed along these lines does not have to be a five star international resort; they can range over a variety of affluence levels and scales to address the varied needs and demands of customers. In practical terms resorts will need to focus on the target markets they can best serve, they will need to draw them to an attractive and healthy setting, and satisfy their expectations in order to convert them into repeat customers or enthusiastic recommenders. What are described as the ‘attract–hold–satisfy’ elements are discussed in the next section.

All resort operations need to consider their future returns on investment (ROI) if they are ever to recoup the extensive capital investments that are called for and they are to become long-term sustainable businesses. Such considerations of present and future development opportunities will involve both their internal business environment, the external physical and social environment of their host community, and global trends – in short an environmental scanning process (Bourgeois, 1980; Daft et al., 1992). Many resorts have been swept up in the dream of creating something special, some without adequate analysis of their competitive situation and sustainable development options.

An example of the enthusiasm for resort development and its potential contribution can be seen in western Canada. A British Columbia task force into resort development would like to see resort development ‘take full advantage of the opportunities provided by the 2010 Olympic and Paralympics Winter Games’. It recommends that in order to achieve this goal a province-wide resort strategy should be created that will provide:

In this way it is hoped to build upon the current C$9.2 billion spent by resort tourists each year in the province, plus increase the current C$178 million in taxes and 26,000 employed in resorts (Minister of State for Resort Development, 2004). In the process the proponents hope to develop more tourism opportunities for British Columbia’s rural regions and to convert more of those resorts into four season operations, which will emulate its star performer – the Whistler/Blackcomb Mountain Four Season Resort.

In Australia a Tourism Task Force (2003, p. 4) report on Australia’s resort situation stated ‘Despite the growth of domestic and international tourism in the last two decades, resorts in Australia have performed poorly from a profitability and investment perspective.’ They reported that Australia’s resorts were achieving lower room yields than city hotels or serviced apartments. Their profitability was low, producing only a gross average return of 10–19 percent before interest, tax and amortization expenses. For the preceding ten years you could have received a guaranteed 5 percent return risk free from Australia’s banks. It comes as no surprise, therefore, that several major Australian resorts have been sold at a loss by their original owners. Such experiences are common around the world, and need to be addressed if resorts are to continue to provide their unique contribution to tourism’s options array.

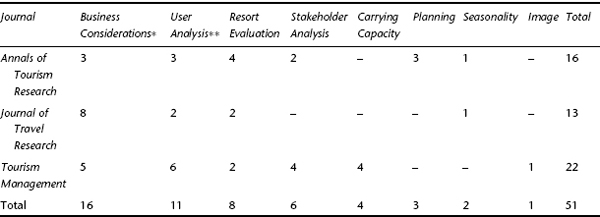

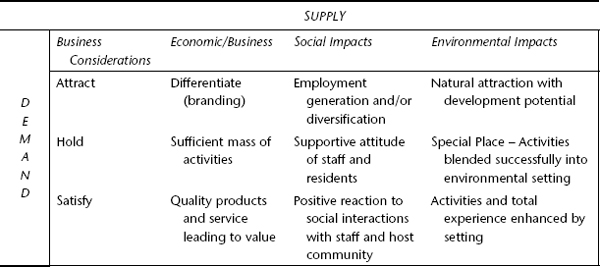

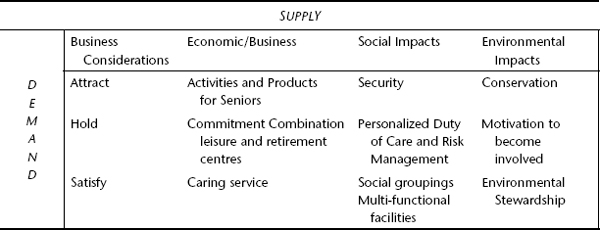

If resorts are to become successful businesses they need to attract a sufficient number of guests throughout the year to provide a satisfactory return on investment and need to use theory to assist them. This will involve an assessment of current conditions and probable future situations. Tables 21.2 and Tables 21.3 represent an attempt to provide a preliminary evaluation matrix to guide such strategic resort management decisions. Since resorts are synonymous with business the matrices have been divided into a demand and supply configuration.

In terms of demand they will need to attract enough visitors throughout the year to make it worth staying open. They should either attract these visitors as pre-booked guests or be able to convert passing through visitors into overnight stays, to provide a sufficient market for its accommodations sector. The resorts need to hold the guest over a few days to give them a chance to experience the full range of recreation and leisure opportunities on display. In the process resorts should increase their yield, as guests sample more of their offerings. The overall goal of resorts is to satisfy their guests and encourage them to either return or become goodwill ambassadors. The first group becomes loyal customers, the second those influential ‘word of mouth’ contacts.

Table 21.2 Evaluation matrix of current challenges

Table 21.3 Evaluation matrix of future challenges

On the supply side, for resorts to become the economic entities that contribute to the array of tourism products and to their host communities’ general welfare, they need to be managed in a sustainable manner. One way to achieve this is to be guided by Elkington’s (1999) triple bottom line audit. This retains an emphasis on the economic–business impacts of the resort, incorporating both economic and business principles to produce a development plan that is both profit-oriented and sustainable. That is joined by social impact assessments to ascertain whether the resort development is having beneficial, benign or negative impacts on local people and the host community. Such assessments look for signs of social and cultural change, along with quality of life measures. The third aspect of the audit is an environmental impact assessment of the resort’s affect on its physical surroundings. This involves utilization of the carrying capacity concept and adoption of the notion of acceptable levels of change.

The above outlines of a possible demand and supply configuration for resort management can be combined with the identified components of each, to provide an evaluation matrix (Tables 21.2 and Tables 21.3). Within the 3 × 3 matrices have been placed some ‘best practice’ options for resort management, based on seeking a sustainable development position using the triple bottom line audit approach in association with identified basic demand functions. The propositions in each cell have been proposed as illustrative key and generic objectives. They are not expected to be complete, since we have seen that resorts are complex and varied tourism products. They should, however, guide individual resorts, at all scales, to assess how well they are addressing their various needs in order to attain sustainability. As in all cases where a complex system is being simplified by dividing it up into component parts, to examine and predict outcomes, some of the cells are likely to overlap. That is, the cells should not be interpreted as being mutually exclusive, but rather as different emphases within a continuing holistic appraisal.

Another thing to note is that evaluation and sustainable development involves examining a moving feast. For we know that tourism is an agent of change and that the local socio-cultural setting and physical landscape are bound to be altered over time by a resort’s presence. We also know that weather conditions and consumer preferences can and will change over time, with some significant potential impacts on the demand for resort vacations. So it is relevant to extend the matrix into the future and attempt to identify some coming trends, hence the division of the evaluation matrices into a ‘current’ and ‘future’ scenario.

The current emphasis for resort management in terms of attracting guests is one of providing a distinctive product within a positive social and environmental setting. So operating horizontally we can see different, yet related, emphases along the three dimensions of the triple bottom line audit (Table 21.2). In economic and business terms, today’s highly competitive global market forces all resorts to stand out by differentiating themselves from their realistic competitors. Many are attempting to do this by applying Porter’s (1980) competitive advantage principles and through branding to increase their top of mind awareness amongst consumers. However, branding a product becomes more challenging as its size and complexity grows, so what might work well for a resort hotel or integrated resort complexes will be harder to achieve with large urban resort destinations. As Kotler et al. (1993, p. 32) observe ‘few places (cities and states) have managed to create strong brand names and images for the products and services they supply’.

The immediate social impacts of resort development, especially in isolated areas, is their employment opportunities, which can either provide welcome new employment or offer a different form of employment to the local area. These economic outcomes of resort development provide significant social benefits, ranging from improved individual quality of life to more extensive social amenities and services.

Part of the attraction to customers and locals will be the increased emphasis on the quality of the local environment, which should be nurtured and developed using sustainable development principles if it is to provide an attractive setting to whatever activity focus has been adopted by the resort. In some cases the natural environment will be an integral part of the resort’s product, in others it will function as a backdrop; but in all cases it must be healthy and attractive in appearance if it is to complement the resort’s business objectives.

Once the guests have arrived they must be held and encouraged to use as many of the provided facilities as possible, if the resort is to maximize its yield. To achieve this a resort will need to provide a sufficient ‘critical’ mass of activities. Critical in the quantity sense that there are enough things to do to hold a guest for a few nights, and in the quality sense of providing logical packages of supporting activities aimed at the same market segments.

Guests should feel welcomed and comfortable in their new setting. An important component to such feelings is the attitude of staff and local residents. If staff are content with the resort’s human resource practices, have received sufficient training and instruction, and feel they are being treated fairly, then they are more likely to provide the sort of superior service resorts strive to offer. If local residents are positive about the resort’s presence and contribution to the local economy they also are likely to be more welcoming.

Guests will feel they have entered a special place if they see a healthy physical setting and don’t see their own waste products. When guests enter a resort they expect to be transported to some wonderful place, as Disney discovered and built on with his ‘fantasy land’ (Bryman, 1995) and Lapidus incorporated into his renown resort hotel designs, such as the Fountainblue and Eden Rock in Miami Beach (Stern, 1986). Part of this fantasy will be a pleasant landscape, often one that is distinctive from the guests’ home environment and one that calls to be photographed. To help maintain the image of these special place landscapes they also need to be protected from the guest, for guests like all travellers pollute and create wear and tear on the environment. It is essential for resorts that are not attached to city water and sewerage systems to provide their own, and to a standard that can leave no doubt about their effectiveness. Consequently, isolated resorts should have clean and tested drinking water systems, backed up so to speak with tertiary or quaternary waste water treatment plants. In addition litter should not be seen, so it should be collected regularly and disposed of in an ecologically friendly manner.

A primary goal of business should be to meet and possibly exceed customer expectations, and thereby satisfy their selected target market. A key ingredient to this will be quality products and service that contribute significantly to the customers’ perceived value of their experience. The provision of quality products is mainly an issue of investment, but ‘the core product being marketed is a performance’ (Berry and Parasuraman, 1991, p. 5), so service quality is required also to achieve a resort’s full potential. All of this has to be synchronized and managed in order to reliably satisfy the guest.

Since a performance on the resort stage involves an interaction between customers and staff and/or residents it is vital to ensure a positive technical and social interaction between the concerned parties. This will involve appropriate training and education for both the technical and social components of the performance. Heskett et al. (1997, p. 11) maintain:

service profit chain thinking maintains that there are direct and strong relationships between profit; growth; customer loyalty; customer satisfaction; the value of goods and services delivered to customers; and employee capability, satisfaction, loyalty, and productivity.

The strongest relationships in this chain have been identified as those between ‘(1) profit and customer loyalty, (2) employee loyalty and customer loyalty, and (3) employee satisfaction and customer satisfaction’ (Heskett et al., 1997, p. 12). Also, ‘Each resort and its site are unique, and (its planning and development) must be adapted to the local situation’ (Inskeep, 1991, p. 211). In resort experiences the environment will be a vital physical contributor to customer satisfaction and resort profit, so the design and placement of buildings should be integrated into the local setting in such a way as to support and reflect the ambience that first attracted the guest. In this manner the resort experience will be enhanced by the setting, and the need for stewardship of that physical setting will be enhanced by its rising value.

The future management priorities for resorts will naturally be a continuation of past and present processes, influenced by future conditions. While forecasting future conditions is not an exact science it is possible to extrapolate certain demographic, economic and environmental circumstances into the future, as environmental scanning currently encourages us to do. In addition to these continuations there will always be random events that will shock the system, which will require some form of contingency planning.

Utilizing the concept that demography represents our destiny, this chapter focuses on one factor that is expected to influence resort futures and is susceptible to management influence, namely the growing presence and influence of our seniors. In terms of economic and business concerns it will focus on the ageing populations in Western countries and their increasing interests in health and retirement options. The social impacts will focus on the growing role of security in these troubled times, especially as it relates to seniors. The environmental impacts will be examined with respect to the gradual degradation that is occurring on this planet and seniors growing role in the world’s conservation movements (Table 21.3).

To attract guests in the future a natural target segment would be the growing seniors market. We can already see a growing interest in health and wellness in many resort locations, and such interest is not confined to the hot springs resorts. The Daydream Island resort in Australia’s Whitsunday Islands has resurrected itself around a wellness theme. What has started will become a major focus as populations age and people seek alternative lifestyles and therapies. In addition to the health facilities guests will be tempted by the light exercise and recreation opportunities provided by many resorts, particularly the golf and swimming pool facilities, and by the healthy menu creations emerging from the various kitchens. Some guests will be so pleased with their pampered body servicing they will be tempted to repeat their visit or even to relocate to the resort. More resorts are accommodating such thoughts with the building of second or retirement homes, which in many cases provide them with the sort of cash flow they need to maintain or enhance the facilities they provide.

On the social impact side the seniors, and other resort visitors, will become more appreciative of resorts’ capacity to offer security. At the lower scales of resort hotel and integrated complexes the privately owned and operated facilities can impose whatever level of security they feel is attractive to their guests. This will involve obvious security checks at the main gate and less obvious but still present security within the building or complex. Such procedures will be more difficult to implement in the more open and public space of a resort destination, but an increase in police budgets and defensive land use and landscaping can be expected.

In terms of environmental impacts, future demand will place an emphasis on the attraction of conservation. As seniors leave behind their long-term homes for the relaxation and retirement of a resort they will want to live among beautiful grounds and healthy nature. They are likely to champion the qualities of their new home environment and want to see its flora and fauna protected, as this is the environment they have chosen for their final days.

To hold guests in the future resorts, especially the seniors, will require resorts to become combination leisure and retirement centres. They will need to find ways to separate the boisterous guests from those seeking tranquillity, and to help manage retirement periods that can last thirty or more years. Under those circumstances the guest will pass from a state of active independence to one of dependency on doctors and nursing, and may well need to move to different forms of housing within the resort. Likewise, the associated recreation facilities will need to embrace a wider range of physical abilities. Swimming pools will need ramps and warmer water, and golf courses easier cart access and playing conditions. This leads to a point where the seniors may well need their own facilities if they are to live out their lives in such medical-resort style retirement.

On the social side risk management will evolve beyond the issues of resort security and financial exposure to involve a more personal assessment of long-term guests’ risk situation – in other words, a more personalized interpretation of the ‘duty of care’ concept. This is underway at present, with the growing health assessment and recommendations role of many wellness centres. As some guests become more regular visitors or permanent residents such assessment and advice can be more formalized, in terms of local medical contacts and hospital visits. Duty of care can be directed to new areas such as guests’ intellectual, hobby and financial interests.

Environmental matters can be expected to take a role in the guests’ education and hobbies area if properly nurtured. Most guests to a resort will have been attracted by its environmental setting, but the seniors will have more time and a stronger motivation to become directly involved. Their strong numbers in National Trust and Audubon societies around the world support their commitment to heritage and the environment. The political knowledge and power of seniors make them a significant lobby for conservation and they are becoming champions for nature enhancement and a greater sense of place.

To satisfy the seniors’ market will require a caring service, one that builds on super service, to include watchfulness and companionship in later years. Future seniors can expect to spend longer in retirement than preceding generations, and some resorts will become quasi-rest homes. They will offer the full range of resort facilities for healthy independent retired couples, and more specialized facilities and smaller units to those who become widowed or who encounter poor health. These specialized units will be in quieter areas, often attached to a central socializing area, and have features such as safety bars in the bathroom, emergency call buttons, and 24-hour nursing assistance on call. Such resort facilities are starting to appear along the coast of Queensland, Australia’s prime retirement state.

The social impact of such developments for the resort is not expected to be major, if appropriate planning and zoning are undertaken. The seniors’ needs are not expected to clash with those of other guests until they seek more solitude and privacy, and then they should find the type of secluded facility as outlined above within the grounds of larger resorts. Their personal social needs should be satisfied to the highest level because the resort setting will provide the type and level of interaction they have voluntarily selected, whilst such a small scale concentration of retirees should make it easier for the surrounding communities to cope with their special needs. It is conceivable that some resort retirement facilities can be utilized by local communities, much the same way as happens currently with some gym, spa and golf club memberships.

In terms of environmental impact the development of resorts with rest home capability or focus are likely to continue with the environmental stewardship referred to earlier. Indeed, one can imagine that as the earth continues to degrade its environment, it will be places like resorts that lead the way in championing local environmental conservation because it is in their own interest. There is a good match between resort environmental approaches and the Winter and Ewers (1989) model of ecological management. ‘In the Winter model there are six principles that are considered essential for the long term success of a responsibly managed company’ (Callenbach et al., 1993, pp. 14–15). These are quality, creativity, humaneness, profitability, continuity and loyalty, all of which have been addressed in some way in Table 21.3.

This chapter has attempted to show that resort management is a distinctive part of general tourism management, with its defining focus on a business venture that needs to attract, hold and satisfy its guests within the threefold description of sustainable development. The very use of the term ‘guest’ over that of consumer or visitor implies that resorts are something special, that they go out of their way to please their customers. Focus on the quality of technical facilities and personal service ensures an emphasis on value, but as in all cases it must be directed at the appropriate and appreciative market segments. The evidence suggests that some resorts in the process of building their spectacular and expensive product have lost sight of making a profit in order to remain sustainable.

In order to assist resort management in developing their triple bottom line sustainability they could adopt a scientific enquiry approach to their strategic decision making. By using existing social science and business theories and techniques resort management could be assisted in achieving the general goal of sustainable development and in their contribution to the overall success of local tourism. Using the theory can assist resort management in clearly identifying, explaining and predicting trends that can be used to prepare for the future, as illustrated in the current and future scenarios used in this chapter.

Current management challenges revolve around the concept of sustainability, based on the profitable conjunction of economic, social and environmental dimensions over an extended period. The period under consideration needs to be extensive because the time line for resorts between conception and opening can extend over several years or decades. While the triple bottom line audit emphasizes the economic viability of an operation, these need to be tempered with social and environmental considerations, each of which can have definite impacts on the bottom line of a resort’s finances. Table 21.2 reveals that, with the appropriate market research and business model, it is possible to blend the three dimensions of the triple audit into a sustainable resort business venture.

The future for resorts seems secure since resorts have survived past historical changes, and to some extent we seem to be experiencing a new Roman period, with a dominant world power and relative prosperity and stability. The paper has chosen to bow to the power and destiny of the god of demographics in this new Roman era, with a focus on the growing seniors market and their expected interest in resort-like retirement. Not all retirees will be drawn to resort temptations, but there are sufficient numbers who believe apparently in ‘spending their children’s inheritance’ to make this a significant segment. Table 21.3 reveals seniors and resorts will be well suited, and that in some situations it would be logical for resorts to become multifunctional by providing both tourist and retirement facilities for some guests.

This chapter considers that resorts will continue to evolve and provide a distinctive component to the overall tourism product. They will continue to appeal to both specialized and mass market segments due to their association with luxury and value. However, their association with quality and value may develop a wider appreciation in the future. It is possible that, as they protect and conserve their local environments for their own purposes, they may be creating oases in an increasingly stressed environment that will become an object of government interest and involvement –as we see with today’s national parks. Likewise, their commitment to a duty of care philosophy combined with profit may tempt government to seek partnerships in areas of providing health services to the elderly and other groups. The seed for such synergies is already in place in the various social tourism policies of some European governments.

Ayala, H. (1991) ‘Resort cycle revisited: The retirement connection’. Annals of Tourism Research, 18(4), 568–87

Berry, B. J. L. and Marble, D. F. (1968) Spatial analysis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall

Berry, B. J. L. and Parasuraman, A. (1991) Marketing services: Competing through quality. New York: Free Press

Bourgeois, L. J., III. (1980) ‘Strategy and environment: A conceptual integration’. Academy of Management Review, 5(1), 25–39

Bryman, A. (1995) Disney and his worlds. London Routledge

Butler, R. W. (ed.) (2006) The tourism area life cycle, Vol. 1. Clevedon: Channel View Publications

Callenbach, E., Capra, F., Goldman, L., Lutz, R. and Marburg, S. (1993) EcoManagement: The Elmwood guide to ecological auditing and sustainable business. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers

Carter, B. and McGoldrick, M. (2005) The expanded family life cycle: Individual family and social perspectives (3rd edn). New York: Pearson

Daft, R. L., Fitzgerald, P. A. and Rock, M. E. (1992) Management. Toronto: Dryden

Economist (2006) ‘Arabian dreams’. The Economist, 4 March, pp. 56–9

Elkington, J. (1999) Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st Century business. Oxford: Capstone Publications

Gee, C. (1996) Resort development and management (2nd edn). East Lansing, MI: Educational Institute of the American Hotel and Motel Association

Haywood, K. M. (2006) ‘Evolution of tourism areas and the tourism industry’. In R. W. Butler (ed.), The tourism area life cycle (Vol. 1). Clevedon: Channel View Publications, pp. 51–69

Heskett, J. L., Sasser, W. E., Jr. and Schlesinger, L. A. (1997) The service profit chain: How leading companies link profit and growth to loyalty, satisfaction, and value. New York: Free Press

Inskeep, E. (1991) Tourism planning: An integrated and sustainable development approach. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold

Kotler, P., Haider, D. H. and Rein, I. (1993) Marketing places. New York: Free Press

Krippendorf, J. (1987) The holiday makers. London: Butterworth-Heinemann

Mill, R. C. (2001) Resorts: Management and operation. New York: John Wiley and Sons

Minister of State for Resort Development (2004) Recommendations of the BC Resort Task Force. Victoria, BC: Author

Murphy, P. E. (1985) Tourism: A community approach. London: Methuen

Murphy, P. E. and Murphy, A. E. (2004) Strategic management for tourism communities: Bridging the gaps. Clevedon: Channel View Publications

Murphy, P. E. and Price, G. G. (2005) ‘Tourism and sustainable development’. In W. F. Theobold (ed.), Global tourism (3rd edn). Burlington, MA: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, pp. 167–93

Pearce, D. G. (1989) Tourist development (2nd edn). Harlow: Longman Scientific and Technical

Pohl, O. (2005) ‘Lazing in lap of luxury, at $16,375 a night’. The Age, 18 March, p. 12

Pojman, L. P. (2003) The theory of knowledge. New York: Wadworth

Porter, M. E. (1980) Competitive strategy. New York: Free Press

Porter, M. E. (1990) The competitive advantage of nations. New York: Free Press

Porter, M. E. (1998) On competition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

Prideaux, B. (2000) ‘The resort development spectrum: A new approach to modeling resort development’. Tourism Management, 21(3), 225–40

Stern, R. A. M. (1986) Pride of place: Building the American dream. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin

Tourism Task Force (2003) Resorting to profitability: Making tourist resorts work in Australia. Sydney: Tourism Task Force

Winter, G. and Ewers, H.-J. (1989) Business and the environment: A Handbook of industrial ecology with 22 checklists for practical use and a concrete example of the integrated system of environmentalist business management Hamburg: McGraw-Hill