PREVIEW

The best place to begin the study of any topic is with an exploration of key concepts. Most of the political terms which concern us are embedded in ordinary language; government, politics, power and authority are all familiar terms. But – as we will see – this does not mean that they are easily defined, or that political scientists are agreed on how best to understand or apply them.

This opening chapter begins with a discussion about the meaning of government and governance, which are related terms but quite different in the ideas they convey: the first focuses on institutions while the second focuses on processes. We then go on to look at politics, whose core features are relatively easy to identify, but whose boundaries are not so clear: does it imply a search for a decision, or a competitive struggle for power? This is followed by a review of the meaning of power, authority, legitimacy and ideology, all of which lie at the heart of our understanding of how government and politics work.

The chapter then examines some of the core purposes of comparative politics; most fundamentally, its study helps us broaden our understanding of politics and government, taking us beyond the limitations inherent in analysing a single political system. We then look at the challenges involved in classifying political systems. Classifications help us make better sense of a large, complex and changing political world – if we could just develop a typology with which everyone could agree.

CONTENTS

• Key concepts: an overview

• Government and governance

• Politics

• Power

• The state, authority, and legitimacy

• Ideology

• Comparative politics

• Classifying political systems

KEY ARGUMENTS

| • The academic study of politics requires few technical terms, but it is useful to identify both a one-sentence definition (concepts) and any issues surrounding the term (conceptions). |

| • A precise definition of politics is difficult, because the term has multiple nuances. But it is clearly a collective activity, leading to decisions affecting an entire group. |

| • Ideology has lost its original meaning as the science of ideas, but it remains useful as a way of packaging different views about the role of government and the goals of public policy. |

| • The concept of governance is increasingly used in political writing, emphasizing the activity rather than the institutions of governing, offering a distinct focus that builds on, rather than supplanting, the more familiar notion of government. |

| • Power is central to politics. But here, again, conceptions are important. If we see persuasion and manipulation as forms of power, the range of the political expands considerably. |

| • Typologies are important as a means of imposing order on the variety of the world’s political systems, and helping us develop explanations and rules. Unfortunately, no typology has yet won general support. |

Key concepts: an overview

In working to understand political terms, we can distinguish between concepts and conceptions. A concept is an idea, term or category such as democracy or power, that is best approached with a definition restricted to its inherent characteristics. In trying to understand the features which a government must possess in order to qualify as a democracy, for example, we can probably agree that some measure of popular control over the rulers is essential; if there were no ways of holding the government to account, there could be no democracy. A good definition of democracy as a concept, in this narrow but important sense, should be clear and concise.

For its part, a conception builds on a concept by describing the understandings, perspectives or interpretations of a concept. We might, for instance, conceive of democracy as self-government, as direct democracy, as representative government or as majority rule. Conceptions build on definitions by moving to a fuller discussion and consideration of alternative positions.

Concept: A term, idea, or category.

Conception: The manner in which something is understood or interpreted.

The book begins with a review of several of the most important concepts involved in comparative pol-itics; to be clear on their meanings will provide the foundations for understanding the chapters that follow.The terms government and politics are routinely used interchangeably, but are not necessarily applied correctly, and terms such as power come in several different forms. We also need to be clear about the definition of the state, and how it relates to authority, legitimacy, and ideology. What all these concepts have in common – apart from the fact that they are central to an understanding of the manner in which human society is organized and administered – is that the precise definition of their meanings is routinely contested. The problem of disputed meanings is found not just in political science, but throughout the social sciences, and there is even some dispute about the meaning of the term social science. It is used here in the context of studying and better understanding the organized relations and interactions of people within society: the institutions they build, the rules they agree, the processes they use, their underlying motives, and the results of their interactions.

Social science: The study of human society and of the structured interactions among people within society. Distinct from the natural sciences, such as physics and biology.

Ultimately, we seek to better understand these concepts so as to enhance our ability to compare. Comparison is one of the most basic of all human activities, lying at the heart of almost every choice we make in our lives. No surprise, then, that it should be at the heart of research in the social sciences. In order to better understand human behaviour, we need to examine different cases, examples, and situations in order to draw general conclusions about what drives people to act the way they do. We can study government and political processes in isolation, but we can never really hope to fully comprehend them, or be sure that we have considered all the explanatory options, without comparison. Only by looking at government and politics across place and time can we build the context to be able to gain a broader and more complete understanding. Within this context, comparative politics involves the systematic study of the institutions, character, and performance of government and political processes in different societies.

Government and governance

This is a book about comparative government and politics, so the logical place to begin our review of concepts is with the term government. Small groups can reach collective decisions without any special procedures; thus the members of a family or sports team can reach an understanding by informal discussion, and these agreements can be self-executing: those who make the decision carry it out themselves. However, such simple mechanisms are impractical for larger units such as cities or states, which must develop standard procedures for making and enforcing collective decisions. By definition, decision-making organizations formed for this purpose comprise the government: the arena for making and enforcing collective decisions.

Government: The institutions and offices through which societies are governed. Also used to describe the group of people who govern (e.g. the Japanese government), a specific administration (e.g. the Putin government), the form of the system of rule (e.g. centralized government), and the nature and direction of the administration of a community (e.g. good government).

In popular use, the term government refers just to the highest level of political appointments: to presidents, prime ministers, legislatures, and others at the apex of power. But in a wider conception, government consists of all organizations charged with reaching and executing decisions for the whole community. By this definition, the police, the armed forces, public servants and judges all form part of the government, even though such officials are not necessarily appointed by political methods such as elections. In this broader conception, government is the entire community of institutions endowed with public authority.

The classic case for the institution of government was made in the seventeenth century by the philosopher Thomas Hobbes (see Focus 1.1). He judged that government provides us with protection from the harm that we would otherwise inflict on each other in our quest for gain and glory. By grant-ing a monopoly of the sword to a government, we transform anarchy into order, securing peace and its principal bounty: the opportunity for mutually beneficial cooperation.

In a democracy, at least, government offers security and predictability to those who live under its jurisdiction. In a well-governed society, citizens and businesses can plan for the long term, knowing that laws are stable and consistently applied. Governments also offer the efficiency of a standard way of reaching and enforcing decisions (Coase, 1960). If every decision had to be preceded by a separate agreement on how to reach and apply it, governing would be tiresome indeed. These efficiency gains give people who disagree an incentive to agree on a general mechanism for resolving disagreements.

FOCUS 1.1 Hobbes’s case for government

The case for government was well made by Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) in his famous treatise Leviathan, published in 1651. His starting point was the fundamental equality in our ability to inflict harm on others:

For as to the strength of body, the weakest has strength enough to kill the strongest, either by secret machination, or by confederacy with others.

So arises a clash of ambition and fear of attack:

From this equality of ability, arises equality of hope in the attaining of our ends. And therefore if any two men desire the same thing, which nevertheless they cannot both enjoy, they become enemies; and in the way to their end, which is principally their own conservation, and sometimes their own delectation, endeavour to destroy or subdue one another.

Without a ruler to keep us in check, the situation becomes grim:

Hereby it is manifest, that during the time men live without a common power to keep them all in awe, they are in that condition which is called war; and such a war, as is of every man, against every man.

People therefore agree (by means unclear) to set up an absolute government to escape from a life that would otherwise be ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short’:

The only way to erect such a common power, as may be able to defend them from the invasion of foreigners, and the injuries of one another… is, to confer all their power and strength upon one man, or one assembly of men, that may reduce all their wills, by plurality of voices, unto one will … This done, the multitude so united is called a COMMONWEALTH.

Source: Hobbes (1651)

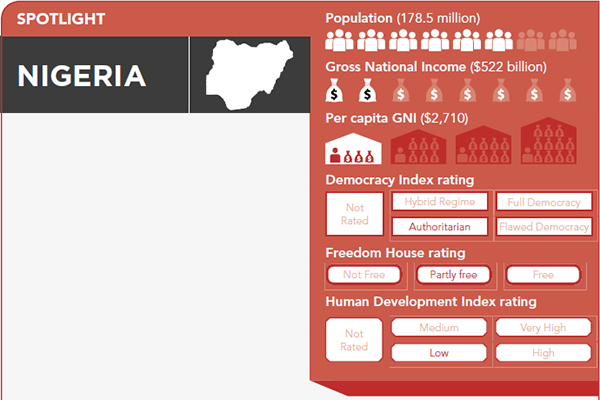

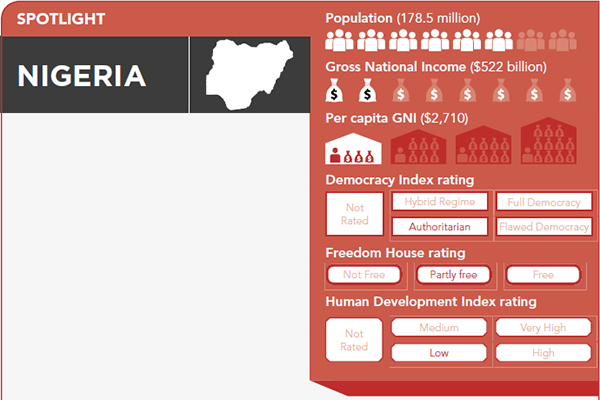

Brief Profile: Although Nigeria has been independent since 1960, it was not until 2015 that it experienced a presidential election in which the incumbent was defeated by an opposition opponent. This makes an important point about the challenges faced by Africa’s largest country by population, and one of the continent’s major regional powers, in developing a stable political form. Nigeria is currently enjoying its longest spell of civilian government since independence, but the military continues to play an important role, the economy is dominated by oil, corruption is rife at every level of society, security concerns and poor infrastructure discourage foreign investment, and a combination of ethnic and religious divisions pose worrying threats to stability. Incursions and numerous attacks since 2002 by the Islamist group Boko Haram, an al-Qaeda ally which controls parts of northern Nigeria, have added to the country’s problems.

Form of government  Federal presidential republic

Federal presidential republic

consisting of 36 states and a Federal Capital Territory. State formed 1960, and most recent constitution

adopted 1999.

Legislature  Bicameral National Assembly: lower House of Representatives (360 members) and upper Senate (109

Bicameral National Assembly: lower House of Representatives (360 members) and upper Senate (109

members), both elected for fixed and renewable four-year terms.

Executive  Presidential. A president elected for a maximum of two four-year terms, supported by a vice president and

Presidential. A president elected for a maximum of two four-year terms, supported by a vice president and

cabinet of ministers, with one from each of Nigeria’s states.

Judiciary  Federal Supreme Court, with 14 members nominated by the president, and either confirmed by the Senate

Federal Supreme Court, with 14 members nominated by the president, and either confirmed by the Senate

or approved by a judicial commission.

Electoral system  President elected in national contest, and must win a majority of all votes cast and at least 25

President elected in national contest, and must win a majority of all votes cast and at least 25

per cent of the vote in at least two-thirds of Nigeria’s states. Possibility of two runoffs. National Assembly elected using

single-member plurality.

Parties  Multi-party, led by the centrist People’s Democratic Party and the conservative All Nigeria People’s Party.

Multi-party, led by the centrist People’s Democratic Party and the conservative All Nigeria People’s Party.

Of course, establishing a government creates new dangers. The risk of Hobbes’s commonwealth is that it will abuse its own authority, creating more problems than it solves. As John Locke – one of Hobbes’s critics – pointed out, there is no profit in avoiding the dangers of foxes if the outcome is simply to be devoured by lions (Locke, 1690). A key aim in studying government must therefore be to discover how to secure its undoubted benefits, while also limiting its inherent dangers. We must keep in mind the question posed by Plato: ‘who is to guard the guards themselves?’

Government and politics in Nigeria

Many of the facets of the debate about government, politics, power, and authority are on show in Nigeria, a relatively young country struggling to develop a workable political form and national identity in the face of multiple internal divisions.

Understanding Nigeria is complicated by the lack

of durable governmental patterns. Since independence in 1960, Nigerians have lived through three periods

of civilian government, five successful and several attempted military coups, a civil war, and nearly 30 years of military rule. The first civilian government (1960– 66) was based on the parliamentary model, but the second and third (1979–83 and 1999–present) were based on the presidential form. Since 2007, Nigeria has twice made the transition from one civilian government to another and the long-term political prognosis has improved. Still, considerable uncertainties remain.

In part, political doubts reflect economic drift. The country’s growing population is expected to double in

the next 25 years, straining an infrastructure that is already woefully inadequate to support a modern economy. Nigeria’s core economic problem is its heavy reliance on oil, which leaves the size and health of the economy – as well as government revenues – dependent on the fluctuating (and currently depressed) price of

oil. To make matters worse, much of the oil wealth has been squandered and stolen, and there have been bitter political arguments over how best to spend the balance.

Nigeria’s problems are more than just economic. In social terms, Nigeria is divided by ethnicity, handicapping efforts to build a sense of national identity. It is also separated by religion, with a mainly Muslim north, a non-Muslim south, and controversial pressures from the north to expand the reach of sharia, or Islamic law. Regional disparities are fundamental, with a north that is dry and poor and a south that is better endowed in resources and basic services. Regional tensions have been made worse by oil, most of which lies either in the southeast or off the coast, but with much of the profit distributed to political elites in other parts of the country.

In democracies, government is influenced by wider forces, such as interest groups, political parties, the media, corporations, and public opinion. In authoritarian systems, the government may lack much autonomy, effectively becoming the property of a dominant individual or clan. One way of referring to the broader array of forces surrounding and influencing government is through the concept of a political system.

Political system: The interactions and organizations (including but not restricted to government) through which a society reaches and successfully enforces collective decisions. Interchangeably used with the term regime, but the latter tends to have negative connotations.

This phrase usefully extends our line of sight beyond official institutions, while still implying that political actors interact with each other and with government in a stable fashion, forming a distinct element or function within society (Easton, 1965). So, the ‘Swedish political system’ means more than ‘Swedish government’; it is the space in which the activity of Swedish politics, or at least the bulk of it, takes place.

Another related concept that has undergone a recent revival is governance, which refers to the whole range of actors involved in government. But where the phrase political system suggests a rather static account based on organizations, the idea of governance highlights the process and quality of collective decision-making, with a particular focus on regulation.The emphasis is on the activity of governing, rather than on the institutions of government, so that we can – for example – speak of the governance (rather than the government) of the internet, because no single government department is in charge.

Governance: The process by which decisions, laws and policies are made, with or without the input of formal institutions.

Governance directs our attention away from government’s command-and-control function towards the broader task of public regulation, a role which ruling politicians in liberal democracies share with other bodies. For example, a particular sport will be run by its governing body, with the country’s government intervening only in extreme situations. Hence, the need for the concept of governance as a supplement, rather than a replacement, for the notion of government.

The notion of governance has been prominent in discussions about the European Union.This 28-member regional integration association has several institutions that look much like an EU government – they include an elected European Parliament and a Court of Justice – but which are better regarded as a system of governance (McCormick, 2015). Their job is to develop policies and laws, and to oversee the implementation of those policies and laws, but they can only do as much as the foundational treaties of the EU, and the governments of its member states, allow them to do.They are better seen as servants of the process of European integration than as the leaders of the EU.

Because governance refers to the activity of ruling, it has also become the preferred term when examining the quality and effectiveness of rule. In this context, governance refers not to the institutions of government but to what they do and to how well they do it. For example, many international agencies suggest that effective governance is crucial to economic development in new democracies (World Bank, 1997). President Obama told Ghana’s parliament in 2009 that ‘development depends upon good governance’ (BBC News, 2009). In this sense of governance, the focus is on government policies and activities, rather than the institutions of rule themselves.

Politics

In the debate over the meaning of politics, we can easily list and agree examples of political activity. When the president and Congress in the United States engage in their annual tussle over the budget, for example, they are clearly engaged in politics.When thousands of the residents of Hong Kong joined street protests in 2014 against the limits on self-determination and democracy imposed by the Chinese government, they, too, were taking part in politics. The political heartland, as represented by such examples, is clear enough.

Politics: The process by which people negotiate and compete in the process of making and executing shared or collective decisions.

However, the boundaries of politics are less precise. When one country invades another, is it engaged in politics or merely in war? When a dictatorship sup-presses a demonstration by violence, is it playing or preventing politics? When a court issues a ruling about privacy, should its judgment be read as political or judicial? Is politics restricted to governments, or can it also be found in businesses, families, and even university classrooms?

A crisp definition of politics – one which fits just those things we instinctively call ‘political’ – is difficult, because the term is used in so many different ways. But three aspects of politics are clear:

• It is a collective activity, occurring between and among people. A lone castaway on a desert island could not engage in politics, but if there were two castaways on the same island, they could have a political relationship.

• It involves making decisions on matters affecting two or more people, typically to decide on a course of action, or to resolve disagreements.

• Once reached, political decisions become authoritative policy for the group, binding and committing its members.

Politics is necessary because of the social nature of humans. We live in groups that must reach collective decisions about using resources, relating to others, and planning for the future. A country deliberating on whether to go to war, a family discussing where to take its vacation, a university deciding whether its priority lies with teaching or research: these are all examples of groups forming judgements impinging on all their members. Politics is a fundamental activity because a group which fails to reach at least some decisions will soon cease to exist. You might want to remove from office the current set of politicians in your country but you cannot eliminate the political tasks for which they are responsible.

Once reached, decisions must be implemented. Means must be found to ensure the acquiescence and preferably the consent of the group’s members. Once set, taxes must be raised; once adopted, regulations must be imposed; once declared, wars must be fought. Public authority – and even force if needed – is used to implement collective policy, and citizens who fail to contribute to the common task may be fined or even imprisoned by the authorities. So, politics possesses a hard edge, reflected in the adverb authoritatively in the famous definition of a political system offered by the political scientist David Easton (1965: 21):

A political system can be designated as the interactions through which values are authoritatively allocated for a society; that is what distinguishes a political system from other systems lying in its environment.

As a concept, then, politics can be defined as the process of making and executing collective decisions. But this simple definition generates many contrasting conceptions. Idealistically, politics can be viewed as the search for decisions which either pursue the group’s common interest or at least seek peaceful reconciliation of the different interests within any group of substantial size. Alternatively, and perhaps more realistically, politics can be interpreted as a competitive struggle for power and resources between people and groups seeking their own advantage. From this second vantage point, the methods of politics can encompass violence as well as discussion.

The interpretation of politics as a community-serving activity can be traced to the ancient Greeks. For instance, the philosopher Aristotle (384–322 bce) argued that ‘man is by nature a political animal’ (1962 edn: 28). By this, he meant not only that politics is unavoidable, but also that it is the highest human activity, the feature which most sharply separates us from other species. For Aristotle, people can only express their nature as reasoning, virtuous beings by participating in a political community which seeks not only to identify the common interest through discussion, but also to pursue it through actions to which all contribute. Thus, politics can be seen as a form of education which brings shared interests to the fore. In Aristotle’s model constitution, ‘the ideal citizens rule in the interests of all, not because they are forced to by checks and balances, but because they see it as right to do so’ (Nicholson, 2004: 42).

A continuation of Aristotle’s perspective can be found today in those who interpret politics as a peaceful process of open discussion leading to collective decisions acceptable to all stakeholders in society.The political theorist Bernard Crick (2005: 21) exemplifies this position:

Politics … can be defined as the activity by which different interests within a given unit of rule are conciliated by giving them a share in power in proportion to their importance to the welfare and the survival of the whole community.

For Crick, politics is neither a set of fixed principles steering government, nor a set of traditions to be preserved. It is instead an activity whose function is ‘preserving a community grown too complicated for either tradition alone or pure arbitrary rule to preserve it without the undue use of coercion’ (p. 24). Indeed, Crick regards rule by dictators, or by violence, or in pursuit of fixed ideologies, as being empty of political activity. This restriction arises because politics is ‘that solution to the problem of order which chooses conciliation rather than violence and coercion’ (p. 30). The difficulty with Crick’s conception, as with Aristotle’s, is that it provides an ideal of what politics should be, rather than a description of what it actually is.

Politics can also involve narrow concerns taking precedence over collective benefits when those in authority place their own goals above those of the wider community. So, we need a further conception, one which sees power as an intrinsic value and politics as a competition for acquiring and keeping power. From this second perspective, politics is viewed as a competition yielding winners and losers. For example, the political scientist Harold Lasswell (1936) famously defined politics as ‘who gets what, when, how’. Particularly in large, complex societies, politics is a competition between groups – ideological, as well as material – either for power itself or for influence over those who wield it. Politics is anything but the disinterested pursuit of the public interest.

Further, the attempt to limit politics to peaceful, open debate seems unduly narrow. At its best, politics is a deliberative search for agreement, but politics as it exists often takes less conciliatory forms. To say that politics does not exist in Kim Jong Un’s North Korea would appear absurd to the millions who live in the dictator’s shadow. A party in pursuit of power engages in politics, whether its strategy is peaceful, violent or both. In the case of war, in particular, it is preferable to agree with the Prussian general Carl von Clausewitz that ‘war is the continuation of politics by other means’ and with Chinese leader Mao Zedong that ‘war is politics with bloodshed’.

Politics, then, has many different facets. It involves shared and competing interests; cooperation and con-flict; reason and force. Each conception is necessary, but only together are they sufficient. The essence of politics lies in the interaction between conceptions, and we should not narrow our vision by reducing politics to either one. As Laver (1983: 1) puts it: ‘Pure conflict is war. Pure cooperation is true love. Politics is a mixture of both.’

Power

At the heart of politics is the distribution and manipulation of power. The word comes from the Latin potere, meaning ‘to be able’, which is why the philosopher Bertrand Russell (1938) sees power as ‘the production of intended effects’. The greater our ability to determine our own fate, the more power we possess. In this sense, describing Germany as a powerful country means that it has a high level of ability to achieve its objectives, whatever those may be. Conversely, to lack power is to fall victim to circumstance. Arguably, though, every state has power, even if it is the kind of negative power involved in obliging a reaction from bigger and wealthier states; Somali pirates, Syrian refugees, and illegal migrants from Mexico may seem powerless, but all three groups spark policy responses from the governments of those countries they most immediately affect.

Power: The capacity to bring about intended effects.The term is often used as a synonym for influence, but is also used more narrowly to refer to more forceful modes of influence: notably, getting one’s way by threats.

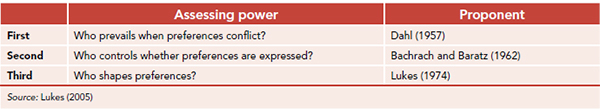

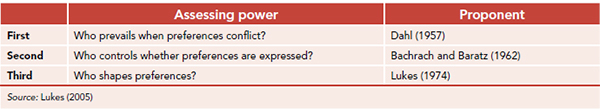

Notice that the emphasis here is on power to rather than power over – on the ability to achieve goals, rather than the more specific exercise of control over other people or countries. But most analyses of power focus on relationships: on power over others. Here, the three dimensions of power distinguished by Steven Lukes (2005) are useful (Table 1.1). Lukes helps to address the question of how we can measure a group’s power, or at least establish whether one group is more powerful than another. As we move through these dimensions, so the conception of power becomes more subtle – but also, perhaps, somewhat stretched beyond its normal use.

The first dimension is straightforward: power should be judged by examining whose views prevail when the actors involved possess conflicting views on what should be done. The greater the correspond-ence between a person’s views and decisions reached, the greater is that person’s influence: more wins indicate more power. This decision-making approach, as it is called, was pioneered by the political scientist Robert Dahl (1961a) in his classic study of democracy and power in the city of New Haven, Connecticut. The approach is clear and concrete, based on identifying preferences and observing decisions, and connecting directly with the concept of politics as the resolution of conflict within groups. Even though it has now been supplemented by Lukes’s other dimensions, it remains a sound initial step in studying power.

The second dimension focuses on the capacity to keep issues off the political agenda. Bachrach and Baratz (1962: 948) give the example of a discontented faculty member who rails against university policy in her office but remains silent during faculty meetings, judging that an intervention there would be ineffective and even damaging to her career. Or perhaps all the major political parties in a particular country advocate free trade, forming what amounts to an elite conspiracy to marginalize trade tariffs and quotas. In these ways, potential ‘issues’ (change university govern-ance; introduce trade controls) become non-issues and the only decisions in these areas are non-decisions – successful attempts to prevent the emergence of topics which would threaten the values or interests of decision-makers.

This second dimension broadens our understanding of the political, taking us beyond the mere resolution of differences and inviting us to address their suppression. In this way, Dahl’s view (1961a: 164) that ‘a political issue can hardly be said to exist unless and until it commands the attention of a significant segment of the political stratum’ is rejected. Rather, the second dimension recognizes what Schattschneider (1960: 71) called the ‘mobilization of bias’:

TABLE 1.1: Lukes’s three dimensions of power

All forms of political organization have a bias in favour of the exploitation of some kinds of conflict and the suppression of others because organization is the mobilization of bias. Some issues are organized into politics, while others are organized out.

To deal with this second dimension, Bachrach and Baratz (1962) recommend that students of power should examine which groups gain from existing political procedures, and how powerful individuals limit the political debate to safe issues. Only then should attention turn to the question of whose views prevail on those matters that are up for debate.

The third dimension broadens our conception of power still further (some say, too far). Here, power is extended to cover the formation, rather than merely the expression, of preferences. Where the first and second dimensions assume conflicting preferences, the third dimension addresses the notion of a manipulated consensus. Hence, for example, a government may withhold information about the risks from a chemical leak, preventing those affected from taking necessary steps to protect their health. More generally, advertising may direct people’s desires towards consumption and away from non-material aspects of life which could offer deeper, or at least more natural, satisfaction of genuine needs.

The implications of these examples is that the most efficient form of power is to shape people’s information and preferences, thus preventing the first and second dimensions from coming into play. Lukes (2005: 24) makes this argument:

Is it not the supreme and most insidious exercise of power to prevent people, to whatever degree, from having grievances by shaping their perceptions, cognitions and preferences in such a way that they accept their role in the existing order of things, either because they can see or imagine no alternative to it, or because they see it as natural and unchange-able, or because they value it as divinely ordained and beneficial?

The case for the third dimension of power is clearest when specific information is denied in a deliberate attempt to manipulate (Le Cheminant and Parrish, 2011). One example can be found in the selective brief-ings initially provided by the power company responsible for operating the Japanese nuclear power station which leaked radiation after the 2011 earthquake.

In general, though, working with power’s third dimension creates difficulties of its own. In the case of advertising, who is to say that the desire for material goods is a false need? And if a materialist culture is simply an unintended and cumulative consequence of advertising, rather than an explicit aim of specific individuals, do we have an instance of power at all? In any case, does not the third face of power take us too far from the explicit debates and decisions which are at the heart of politics?

The state, authority, and legitimacy

We will consider the state in more detail in Chapter 2, but a brief preview is merited here. The world is divided into nearly 200 states (the exact number, as we will see, is debatable), each containing a population living within a defined territory, and enjoying recognition by its residents and by other states of its right to rule that territory. States are also known as countries, but the state is the more political term. The state provides the legal or formal mandate for the work of governments, allowing them to utilize the authority inherent in the state. More immediately for the purposes of comparative politics, states are the core guiding unit of comparison. We can compare government and politics at multiple levels, from the national to the local, but is the state that will provide us with our most important point of reference as we work through the complexities of comparison.The state is also intimately related to two concepts that lie at the heart of our understanding of government and politics: authority and legitimacy.

Authority is a broader concept than power and in some ways more fundamental to comparative politics. Where power is the capacity to act, authority is the acknowledged right to do so. It exists when subordi-nates accept the capacity of superiors to give legitimate orders, so that while an army general may exercise power over enemy soldiers, his authority is restricted to his own forces. The German sociologist Max Weber (1922: 29) suggested that, in a relationship of authority, the ruled implement the command as if they had adopted it spon-taneously, for its own sake. For this reason, authority is a more efficient form of control than brute power.Yet, authority remains more than voluntary compliance. To acknowledge the authority of your state does not mean you always agree with its decisions; it means only that you accept its right to make them and your own duty to obey. In this way, authority provides the foundation for the state.

Authority: The right to rule. Authority creates its own power, so long as people accept that the person in authority has the right to make decisions.

Just as there are different sources of power, so too can authority be built on a range of foundations. Almost 100 years ago, Weber distinguished three ways of vali-dating political power: by tradition (the accepted way of doing things), by charisma (intense commitment to the leader and his message) and by appeal to legal–rational norms (based on the rule-governed powers of an office, rather than a person) (Weber, 1922). This classification remains useful, even though today legal–rational authority is pre-eminent in stable democracies.

Legitimacy builds on, but is broader than, authority. When a regime is widely accepted by those subject to it, and by other regimes with which it deals, we describe it as legitimate. Thus, we speak of the authority of an official but the legitimacy of a regime. Although the word legitimacy comes from the Latin legitimare, meaning ‘to declare lawful’, legitimacy is much more than mere legality.Where legality is a technical matter, referring to whether a rule was made correctly by following regular procedures, legitimacy is a more political concept. It refers to whether people accept the authority of the political system.Without this acceptance, the very existence of a state is in question.

Legitimacy: The state or quality of being legitimate. A legitimate system of government is one based on authority, and those subject to its rule recognize its right to make decisions.

Legality is a topic for lawyers; political scientists are more interested in issues of legitimacy: how a political system gains, keeps, and sometimes loses public faith in its right to rule. A flourishing economy, international success, and a popular governing party will boost the legitimacy of a political system, even though legitimacy is more than any of these things. In fact, one way of thinking about legitimacy is as the credit a political system has built up from its past successes, a reserve that can be drawn down in bad times. In any event, public opinion – not a law court – is the test of legitimacy. And it is legitimacy, rather than force alone, which provides the most stable foundation for rule.

Ideology

The concepts reviewed so far have mainly been about politics, but ideas also play a role in politics: political action is motivated by the ideas people hold about it. One way to approach the role of ideas is via the notion of ideology, a term which was coined by the French philosopher Antoine Destutt de Tracy during the 1790s, in the aftermath of the French Revolution, to describe the science of ideas. Its meaning has long since changed, and it now denotes packages of ideas related to different views about the role of government and the goals of public policy. An ideology is today understood as any system of thought expressing a view on:

• human nature

• the proper organization of, and relationship between, state and society

• the individual’s position within this prescribed order.

Ideology: A system of connected beliefs, a shared view of the world, or a blueprint for how politics, economics and society should be structured.

Which specific political outlooks should be regarded as ideologies is a matter of judgement, but Figure 1.1 offers a selection. In any case, the era of explicit ideology beginning with the French Revolution ended in the twentieth century with the defeat of fascism in 1945 and the collapse of communism at the end of the 1980s. Ideology seemed to have been destroyed by the mass graves it had itself generated. Of course, intellectual currents – such as environmental concerns, feminism, and Islamism – continue to circulate. Even so, it is doubtful whether the ideas, values, and priorities of our century constitute ideologies in the classical sense. To describe any perspective, position, or priority as an ideology is to extend the term in a manner that bears little relation to its original interpretation as a coherent, secular system of ideas.

FIGURE 1.1: Five major ideologies

Even though the age of ideology may have passed, we still tend to talk about ideologies, placing them on a spectrum between left and right. The origins of this habit lie in revolutionary France, where – in the legislative assemblies of the era – royalists sat to the right of the presiding officer, in the traditional position of honour, while radicals and commoners sat to the left. To be on the right implied support for aristocratic, royal and clerical interests; the left, by contrast, favoured a secular republic and civil liberties.

The words ‘left’ and ‘right’ are still commonly encountered in classifying political parties. Hence the left is associated with equality, human rights, and reform, while the right favours tradition, established authority and pursuit of the national interest. The left supports policies to reduce inequality; the right is more accepting of natural inequalities. The left sympathizes with cultural and ethnic diversity; the right is more comfortable with national unity. (See Table 1.2 for more details.) Surveys suggest that most voters in democracies can situate themselves as being on the left or right, even if many simply equate these labels with a particular party or class (Mair, 2009: 210).

Although the terms left and right have travelled well throughout the democratic world, enabling us to compare parties and programmes across countries and time, the specific issues over which these tendencies compete have varied, and the terms are better seen as labels for containers of ideas, rather than as well-defined ideas in themselves. The blurring of the distinction can be seen in Europe, where the left (socialists and communists)

TABLE 1.2: Contrasting themes of left and right

| Left | Right |

| Peace | Armed forces |

| Internationalism | National way of life |

| Democracy | Authority, morality, and the constitution |

| Planning and public ownership | Free market |

| Trade protection | Free trade |

| Social security | Social harmony |

| Education | Law and order |

| Trade unions |

Freedom and rights |

Note: Based on an analysis of the programmes of left- and rightwing political parties in 50 democracies, 1945–98.

Source: Adapted from Budge (2006: 429)

once favoured nationalization of industries and services, and the right (conservatives) supported a free market, but the widespread acceptance of the market economy has meant that the concepts of left and right have lost some bite.

Comparative politics

The core goal of comparative politics is to understand how political institutions and processes operate by examining their workings across a range of countries. Comparison has many purposes, including the simple description of political systems and institutions, helping us understand the broader context within with they work, helping us develop theories and rules of politics, and showing us how similar problems are approached by different societies. But two particular purposes are worth elaboration: broadening our understanding of the political world, and predicting political outcomes.

Comparative politics: The systematic study of government and politics in different countries, designed to better understand them by drawing out their contrasts and similarities.

Broadening understanding

The first strength of a comparative approach is straightforward: it improves our understanding of government and politics. Through comparison we can pin down the key features of political institutions, processes and action, and better appreciate the dynamics and character of political systems. We can study a specific government, legislature, party system, social movement, or national election in isolation, but to do so is to deny us the broader context made possible by comparison. How could we otherwise know if the object of our study was unusual or usual, efficient or inefficient, the best option available or significantly lacking in some way?

When we talk of understanding, it is not only the need to comprehend other political systems, but also to understand our own. We can follow domestic politics closely and think we have a good grasp on how it works, but we cannot fully understand it without comparing it with other systems; this will tell us a great deal about the nature of our home system. Consider the argument made by Dogan and Pelassy (1990: 8):

Because the comprehension of a single case is linked to the understanding of many cases, because we perceive the particular better in the light of generali-ties, international comparison increases tenfold the possibility of explaining political phenomena. The observer who studies just one country could interpret as normal what in fact appears to the compara-tivist as abnormal.

Comparison also has the practical benefit of allowing us to learn about places with which we are unfamiliar. This point was well-stated long ago by W. B. Munro (1925: 4) when he wrote that his book on European governments would help readers understand ‘daily news from abroad’. This ability to interpret overseas events grows in importance as the world becomes more interdependent, as events from overseas have a more direct impact on our lives, and as we find that we can no longer afford to think as did Mr Pod-snap in Charles Dickens’s Our Mutual Friend when he quipped that ‘Foreigners do as they do sir, and that is the end of it’.

Understanding politics in other systems not only helps us interpret the news, but also helps with practical political relationships. For instance, British government ministers have a patchy track record in negotiating with their European Union partners, partly because they assume that the aggressive tone they adopt in the chamber of the House of Commons will work as well in Brussels meeting rooms. This assumption reflects ignorance of the consensual political style found in many continental European democracies.

Predicting political outcomes

Comparison permits generalizations which have some potential for prediction. Hence a careful study of, say, campaigning and public opinion will help us better understand the possible outcome of elections. For example, we know from a study of those European countries where proportional representation is used that its use is closely tied to the presence of more political parties winning seats and the creation of coalition governments. Similarly, if we know that subcontracting the provision of public services to private agencies increases their cost-effectiveness in one country, governments elsewhere will see that this is an idea at least worth considering.

If the explanation of a phenomenon is sound, and all the relevant factors have been reviewed and considered, then it follows that our explanations should allow us to predict with at least a high degree of accuracy, if not with absolute certainty. But while the study of the natural sciences has generated vast numbers of laws that allow us to predict natural phenomena, the social sciences have not fared so well. They do not generate laws so much as theories, tendencies, likelihoods, adages, or aphorisms. A famous example of the latter is Lord Acton’s that ‘Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely’ (see Chapter 4). While the idea contains much truth, it is not a rule or a law, and thus cannot be used either to explain or to predict with absolute certainty.

In politics, predicting is an art rather than a science, and a fallible one at that. Even so, the potential for prediction provides a starting point for drawing lessons across countries (Rose, 2005). Rather than resorting to ideology or complete guesswork, we can use comparison to consider ‘what would happen if…?’ questions. This function of comparative research perhaps underpinned Bryce’s comment on his early study of modern democracies (1921: iv):

Many years ago, when schemes of political reform were being copiously discussed in England, it occurred to me that something might be done to provide a solid basis for judgement by examining a certain number of popular governments in their actual working, comparing them with one another, and setting forth the various merits and demerits of each.

In fact there are some who argue that political science generally has done a poor job of helping us predict, while others argue that it should not – or cannot – be in the business of predicting to begin with. Karl Popper (1959: 280) long ago asserted that long-term predictions could only be developed in regard to systems that were ‘well-isolated, stationary, and recur-rent’, and human society was not one of them. More recently, an opinion piece in the New York Times (Stevens, 2012) raised hackles when it argued that in terms of offering accurate predictions, political science had ‘failed spectacularly and wasted colossal amounts of time and money’. It went on to assert that no political scientist foresaw the break-up of the Soviet Union, the rise of al-Qaeda or the Arab Spring. It quoted an award-winning study of political experts (Tetlock, 2005) which concluded that ‘chimps randomly throwing darts at the possible outcomes would have done almost as well as the experts’. To be fair, however, comparative politics is still very much a discipline in the process of development, and we will see many instances throughout this book where understanding of institutions or processes is still in its formative stages.

Classifying political systems

Although the many states of the world have systems of government with many core elements in common – an executive, a legislature, courts, a constitution, parties, and interest groups, for example – the manner in which these elements work and relate to one another is often different. The results are also different: some states are clearly democratic, some are clearly authoritarian, and others sit somewhere between these two core points of reference. To complicate matters, these systems of government, and their related policies and priorities, are moving targets: they evolve and change, and often at a rapid pace. In order to make sense of this confusing picture, it is helpful to have a guide through the maze.

A typology is a system of classification that divides states into groups or clusters with common features. With this in hand, we can make broad assumptions about the states in each group, using case studies to provide more detailed focus, and thus work more easily to develop explanations and rules, and to test theories of political phenomena (Yin, 2013: 21).The ideal typology is one that is simple, neat, consistent, logical, and as real and useful to the casual observer as it is to journalists, political leaders, or political scientists. Unfortunately, such an ideal has proved hard to achieve; scholars of comparative politics disagree about the value of typologies, and even those who use them cannot agree on the criteria that should be taken into account, or the groups into which states should be divided. The result is that there is no universally agreed system of political classification.

Typology: A system of classification by which states, institutions, processes, political cultures, and so on are divided into groups or types with common sets of attributes.

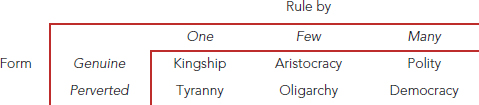

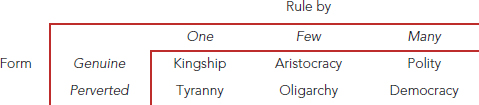

The first such system devised – and one of the earliest examples of comparative politics at work – was Aristotle’s classification of the 158 city-states of ancient Greece. Between approximately 500 and 338 bce, these communities were small settlements showing much variety in their forms of rule. Such diversity provided an ideal laboratory for Aristotle to consider which type of political system provided what he looked for in a government: stability and effectiveness.

Aristotle based his scheme on two dimensions. The first was the number of people involved in the task of governing: one, few or many. This dimension captured the breadth of participation in a political system. His second dimension, more difficult to apply but no less important, was whether rulers governed in the common interest (‘the genuine form’) or in their own interest (‘the perverted form’). For Aristotle, the significance of this second aspect was that a political system would be more stable and effective when its rulers governed in the long-term interests of the community. Cross-classifying the number of rulers with the nature of rule yielded the six types of government shown in Figure 1.2.

Another example of an attempt to build a typology was The Spirit of the Laws, a treatise on political theory written by Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu, and first published in 1748. Montesquieu identified three kinds of political system: republican systems in which the people or some of the people have supreme power, monarchical systems in which one person ruled on the basis of fixed and established laws, and despotic systems in which a single person ruled on the basis of their own priorities and perspectives.

Both typologies remain interesting as historical examples, but they reflected political realities that have long since changed. A more recent example that was current through much of the Cold War (late 1940s–early 1990s) was the Three Worlds system. This was less a formal classificatory template developed by political scientists than a response to geopolitical realities, dividing the world into three groups of countries based on ideological goals and political alliances:

• First World: wealthy, democratic industrialized states, most of which were partners in the Western alliance against communism.

• Second World: communist systems, including most of those states ranged against the Western alliance.

• Third World: poorer, less democratic, and less developed states, some of which took sides in the Cold War, but some of which did not.

Three Worlds system: A political typology that divided the world along ideological lines, with states labelled according to the side they took in the Cold War.

The system was simple and evocative, providing neat labels that could be slipped with ease into media headlines and everyday conversation: even today the term Third World conjures up powerful images of poverty, underde-velopment, corruption, and political instability. But it was always more descriptive than analytical in the Aristotelean spirit, and was dangerously simplistic: the First and Second Worlds had the most internal logic and consistency, but to consider almost all the emerging states of Africa, Asia, and Latin America as a single Third World was asking too much: some were democratic while others were authoritarian; some were wealthy while others were poor; and some were industrialized while others were agrarian. The end of the Cold War meant the end of this particular typology.

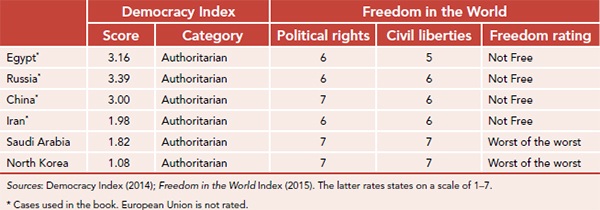

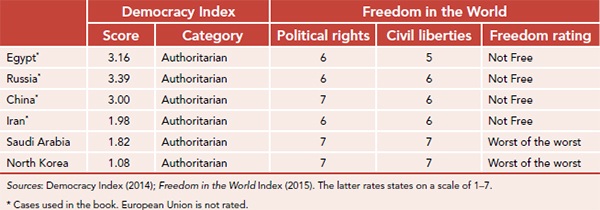

While nothing has replaced it (in the sense of having won general support), there have been many candidates. Two in particular – the Democracy Index maintained by the Economist Intelligence Unit, and the Freedom in the World index maintained by Freedom House – are among the most often quoted, and will be used for guidance in this book (see Focus 1.2).They are not perfect, questions can be asked about the method-ologies upon which they are based, we should take into consideration the agendas and values of the EIU and Freedom House, and we should beware the danger of taking classifications and rankings too literally; government and politics are too complex to be reduced to a single table. Nonetheless, these rankings give us a useful point of reference and a guide through an otherwise confusing world.

FIGURE 1.2: Aristotle’s classification of governments

Source: Aristotle (1962 edn, book 3, ch. 5)

FOCUS 1.2 Two options for classifying political systems

With political scientists unable to develop and agree a single detailed classification of political systems, it has been left to the non-academic world to step into the breach. The two most compelling typologies are the following:

• The UK-based Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU, related to The Economist, a British weekly news magazine) maintains a Democracy Index based on sixty different ratings, giving states a score out of 10 (Norway ranks highest with 9.93 and North Korea lowest with 1.08), and dividing them into four groups: full democracies, flawed democracies, hybrid regimes, and authoritarian regimes. It achieves its rankings by considering such factors as the protection of basic political freedoms, the fairness of elections, the security of voters, election turnout rates, the freedom of political parties to operate, the independence of the judiciary and the media, and arrangements for the transfer of power. See Focus 3.2 and 4.1 for more details.

• The Freedom in the World index has been published annually since 1972 by Freedom House, a US-based research institute. It divides states into groups rated Free, Partly Free, or Not Free based on their records with political rights (including the ability of people to participate in the political process) and civil liberties (including freedom of expression, the independence of the judiciary, personal autonomy, and economic rights). Several countries – including Syria and North Korea – are ranked Worst of the Worst.

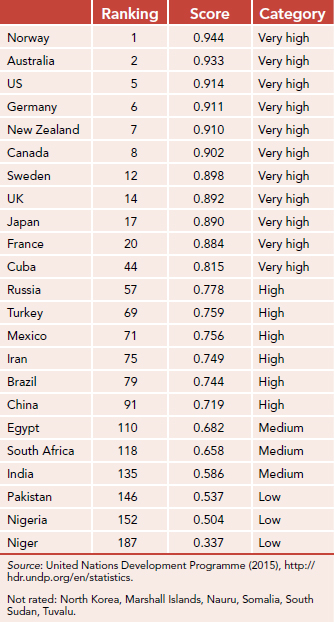

Table 1.3 combines the results of these typologies, focusing on the 16 cases used in this book, while also including examples of countries with the highest and lowest scores on each index.

TABLE 1.3: Comparative political ratings

We will go further and also use some economic and social data to help us find our way through the maze. The relationship between politics and economics in particular is so intimate that there is an entire field of study – political economy – devoted to its examination. This involves looking not just at the structure and wealth of economies, but also at the influences on economic performance: good government is more likely to produce a successful economy, and bad government less so.

Political economy: The relationship between political activity and economic performance.

The core measure is economic output. There are various ways of measuring this, the most popular today being gross national income (GNI) (see Table 1.4). This is the sum of the value of the domestic and foreign economic output of the residents of a country in a given year, and is usually converted to US dollars to allow comparison. Although the accuracy of the data varies by country, and the conversion to dollars raises additional questions about the appropriate exchange rate, such measures are routinely used by governments and international organizations in measuring economic size. While GNI provides a measure of the absolute size of national economies, it does not take into account population size. For a more revealing comparison, we use per capita GNI, which gives us a better idea of the relative economic development of different states.

Table 1.4: Comparing economic size

Gross national income: The total domestic and foreign output by residents of a country in a given year.

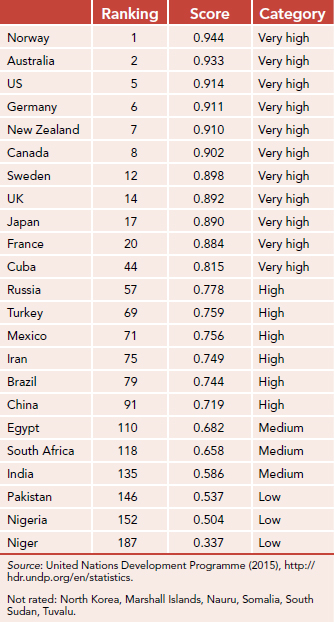

Finally, we must not forget the importance of gaug-ing the performance of political systems by looking at their relative performance in terms of providing their citizens with a good quality of life, as measured by the provision of basic needs. There are different ways of understanding ‘basic needs’, but at a minimum they would include adequate nutrition, education, and health care, and in this regard the most often-used comparative measure of social conditions is offered through the Human Development Index maintained by the UN Development Programme. Using a combination of life expectancy, adult literacy, educational enrolment, and per capita GNI, it rates human development for most of the states in the world as either very high, high, medium, or low. On the 2013 index, most democracies were in the top 30, while the poorest states ranked at the bottom of the table, with Niger in last place at 187 (see Table 1.5).

TABLE 1.5: Human Development Index

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

• What is the purpose of government?

• What is politics? Where does it begin and end?

• Who has power, who does not, and how do we know?

• Does it necessarily follow that to be a democracy is to be legitimate, and to be legitimate is to be a democracy?

• Are the ideological distinctions in modern political systems as important and as clear as they once were?

• What are the strengths and weaknesses of the Democracy Index and Freedom in the World schemes as means of classifying political systems?

KEY CONCEPTS

Authority

Comparative politics

Concept

Conception

Governance

Government

Gross national income

Ideology

Legitimacy

Political economy

Political system

Politics

Power

Social science

Three Worlds system

Typology

FURTHER READING

Crick, Bernard (2005) In Defence of Politics, 5th edn. A forceful exposition of the nature of politics that finds the essence of the subject in the peaceful reconciliation of interests.

Finer, S. E. (1997) The History of Government from the Earliest Times, three vols. Offers a monumental and, in many ways, unequalled history of government.

Heywood, Andrew (2012) Political Ideologies: An Introduction, 5th edn. An informative and wide-ranging textbook that successfully introduces influential political creeds and doctrines.

Lukes, Steven (2005) Power: A Radical View, 2nd edn. This book introduces power’s third face, offering a powerful and engaging critique of conventional interpretations.

Stilwell, Frank (2011) Political Economy:The Contest of Economic Ideas, 3rd edn. A survey of political economy and its links with social concerns.

Woodward, Kath (2014) Social Sciences:The Big Issues, 3rd edn. A useful general survey of the social sciences and the kinds of issues they include.

Federal presidential republic

Federal presidential republic Bicameral National Assembly: lower House of Representatives (360 members) and upper Senate (109

Bicameral National Assembly: lower House of Representatives (360 members) and upper Senate (109 Presidential. A president elected for a maximum of two four-year terms, supported by a vice president and

Presidential. A president elected for a maximum of two four-year terms, supported by a vice president and Federal Supreme Court, with 14 members nominated by the president, and either confirmed by the Senate

Federal Supreme Court, with 14 members nominated by the president, and either confirmed by the Senate President elected in national contest, and must win a majority of all votes cast and at least 25

President elected in national contest, and must win a majority of all votes cast and at least 25 Multi-party, led by the centrist People’s Democratic Party and the conservative All Nigeria People’s Party.

Multi-party, led by the centrist People’s Democratic Party and the conservative All Nigeria People’s Party.