PREVIEW

So far we have looked mainly at broad concepts and ideas in comparative politics, including theoretical approaches and research methods. We now focus on institutions, opening in this chapter with a review of constitutions and the courts that support them. Constitutions tell us much about the goals and purposes of government, as well as the rights of citizens, while courts strive to make sure that these rules are respected and equally applied. Just as humans are imperfect, so are the political institutions they create and manage; there are significant gaps, in other words, between constitutional ideals and practice.

The chapter begins with an assessment of constitutions: what they are, the purposes they serve, their character and durability, how their performance can be measured, and how they are changed.There is no fixed template for constitutions, they vary enormously in terms of their length and efficacy, and the gap between aspiration and achievement differs from one constitution to another.

The chapter goes on to look at the role of courts and their relationship with constitutions, examining the differences between supreme courts and constitutional courts, and the incidence of judicial activism. It then addresses the manner in which judges are recruited, the terms of their tenure, and how such differences impact judicial independence. It then briefly reviews the three major legal systems found in the world – common law, civil law, and religious law – before assessing the often modest place of constitutions and courts in authoritarian regimes.

CONTENTS

• Constitutions and courts: an overview

• The character of constitutions

• The durability of constitutions

• The role of courts

• Judicial activism

• Judicial independence and recruitment

• Systems of law

• Constitutions and courts in authoritarian states

KEY ARGUMENTS

| • Constitutions are critical to achieving an understanding of government, providing – as they do – a power map containing key political principles and rules. |

| • Understanding governments requires an appreciation of the content of constitutions, as well as their durability and how they are amended. |

| • Awareness of the structure and role of courts is also critical, as is the distinction between supreme courts and constitutional courts. |

| • Judicial activism has become an increasingly important concept, as judges have become more willing to enter political arenas. In turn, the rules on judicial recruitment – and their impact on judicial independence – must be taken into consideration. |

| • In comparing constitutions and courts, the distinction between common and civil law has long been important, and more attention needs to be paid to the political signifi cance of religious law. |

| • In authoritarian regimes, constitutions and courts are weak, with governments either using them as a facade or entirely bypassing them. |

Constitutions and courts: an overview

A constitution is a power map containing a set of principles and rules outlining the structure and powers of a system of government, describing its institutions and the manner in which they work and relate to one another, and typically describing both the limits on governmental power and the rights of citizens. A system of government without a constitution is not a system at all, but rather an unorgan-ized collection of habits that can be changed at the whim of the leaders or the people. In the case of democracies, the authority provided by a constitution helps provide predictability and security. In the case of authoritarian regimes, the constitution is more often a fig leaf behind which elites hide, the terms of the constitution being interpreted to suit their needs, or ignored altogether. As well as providing the rules of government, constitutions also offer benchmarks against which the performance of government can be measured.

Constitution: A document or a set of documents that outlines the powers, institutions, and structure of government, as well as expressing the rights of citizens and the limits on government.

Recent decades have seen a growth of interest in the study of constitutions, for four main reasons:

• We have seen an explosion of constitution-making, with 99 countries adopting new constitutions between 1990 and 2012 (Comparative Constitutions Project, 2015).

• Judges and courts in many liberal democracies have become more willing to step into the political arena, not least in investigating corrupt politicians.

• The growing interest in human rights lends itself to judicial engagement.

• The expanding body of international law increasingly impinges on domestic politics, with judges called on to arbitrate the conflicting claims of national and supranational law.

A key link between constitutions, law and government is found in the idea of the rule of law. In the words of the nineteenth-century English jurist, A. V. Dicey (1885: 27), the purpose of the rule of law is to substitute ‘a government of laws’ for a ‘government of men’. When rule is by law, political leaders cannot exercise arbitrary power and the powerful are (in theory, at least) subject to the same laws as everyone else. More specifically, the rule of law implies that laws are general, public, prospective, clear, consistent, practical, and stable (Fuller, 1969).

Rule of law: The idea that societies are best governed using laws to which all the residents of a society are equally subject regardless of their status or background.

The implementation of the rule of law and due process (respect for an individual’s legal rights) is perhaps the most important distinction between liberal democracies and authoritarian regimes. In the case of the latter, the adoption and application of laws is more arbitrary, and based less on tried and tested principles than on the political goals and objectives of top leaders. No country provides completely equal application of the law, but democracies fare much better than authoritarian regimes, many of whose political weaknesses stem back to constitutional weaknesses.

The character of constitutions

Most constitutions are structured similarly in the sense that they include four elements (see Figure 7.1). They often start out with a set of broad aspirations, declaring in vague but often inspiring terms the ideals of the state, most often including support for democracy and equality. The core of the document then goes into detail on the institutional structure of government: how the different offices are elected or appointed, and what they are allowed and not allowed to do. There will usually be a bill of rights or its equivalent, outlining the rights of citizens relative to government. Finally, there will be a description of the rules on amending the constitution.

Much is made of the distinction between written and unwritten constitutions, and yet no constitution is wholly unwritten; even the ‘unwritten’ British and New Zealand constitutions contain much relevant statute and common law. A contrast between codified and uncodified systems is more helpful. Most constitutions are codified; that is, they are set out in detail within a single document. By contrast, the uncodified constitutions of Britain and New Zealand are spread out among several sources; in the British case, these include statute and common law, European law, com-mentaries written by constitutional experts, and customs and traditions. Establishing the age of uncodified constitutions is far from easy. Britain, for example, does not have (a) a single document that was (b) drawn up at a particular point in time and (c) went into force on a given date (three features of most of the world’s codified constitutions). But the distinction between codified and uncodified is not always neat and tidy. Sweden falls somewhere in between, because its constitution comprises four separate acts passed between 1810 and 1991.

FIGURE 7.1: The elements of constitutions

Codified constitution: One that is set out in a single document.

Uncodified constitution: One that is spread among a range of documents and is influenced by tradition and practice.

We can look at constitutions in two ways. First, they have a historic role as a regulator of a state’s power over its citizens. For the Austrian philosopher Friedrich Hayek (1899–1992), a constitution was nothing but a device for limiting the power of government, whether unelected or elected. In similar vein, the German-American political theorist Carl Friedrich (1901– 84) defined a constitution as ‘a system of effective,regularized restraints upon government action’ (1937: 104). From this perspective, the key feature of a constitution is its statement of individual rights and its expression of the rule of law. In this sense, constitutions express the overarching principles within which non-constitutional law – and the legal system, generally – operates.

A bill of rights now forms part of nearly all written constitutions. Although the US Bill of Rights (1791) confines itself to such traditional liberties as freedom of religion, speech, and assembly, recent constitutions are more ambitious, often imposing duties on rulers such as fulfilling the social rights of citizens to employment and medical care. Several post- communist constitutions have extended rights even further, to include childcare and a healthy environment. As a result, the documents are expanding: the average length (including amendments) is now 29,000 words (Lutz, 2007).

The second, more political and more fundamental role of constitutions is to outline a power map, defining the structure of government, identifying the pathways of power, and specifying the procedures for law- making. As Sartori (1994: 198) observes, the key feature of a constitution lies in this provision of a frame of government. A constitution without a declaration of rights is still a constitution, whereas a document without a power map is no constitution at all. A constitution is therefore a form of political engineering – to be judged, like any other construction, by how well it survives the test of time.

In the main, constitutions are a deliberate creation, designed and built by politicians and typically forming part of a fresh start after a period of disruption. Such circumstances include:

• Regime change, as in the wake of break-up in the 1990s of the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia, and of Sudan in 2011.

• Efforts to bring about wholesale political change or confirm agreements made between competing political groups, as in the cases of Bolivia (2009), Kenya (2010), Zimbabwe (2013), and Tunisia (2014).

• Reconstruction after defeat in war, as in the case of Japan after 1945 or Iraq after 2005.

• Achieving independence, as in the case of much of Africa in the 1950s and 1960s, or the 15 republics created by the break-up of the Soviet Union.

New constitutions are typically written by conventions of politicians, usually working in closed session. The voice of ‘the people’ is directly heard only if a state holds a referendum to ratify the new constitution. Many countries, including the United States, have never held such a vote. Interestingly, Iceland recently tried an exceptionally open process in constitution-crafting. It engaged a group of citizens to list priorities for a new constitution, and appointed a different set of citizens to undertake the drafting. Social media were then used to elicit comments on a draft, which was approved in a non-binding 2012 referendum but failed to win legislative support in 2013.

Constitutions often experience a difficult birth, particularly when they are compromises between political actors who have substituted distrust for conflict. In Horowitz’s terms (2002), constitutions are built from the bottom up, rather than designed from the top down. For instance, South Africa’s post-apartheid settlement of 1996 achieved a practical accommodation between leaders of the white and black communities against a backdrop of near slavery and continuing racial hostility. Acceptability was everything; elegance was nothing – see Spotlight.

As vehicles of compromise, most constitutions are vague, contradictory, and ambiguous. They are fudges and truces, wrapped in fine words (Weaver and Rockman, 1993). As a rule, drafters are more concerned with a short-term political fix than with establishing a resilient structure for the long run. In principle, everyone agrees with Alexander Hamilton (1788a: 439), that constitutions should ‘seek merely to regulate the general political interests of the nation’; in practice, they are often lengthy documents reflecting an incomplete settlement between suspicious partners. The US constitution, though shorter than most, is no exception, being – in the words of Finer (1997: 1495) – ‘a thing of wrangles and compromises. In its completed state, it was a set of incongruous proposals cobbled together. And furthermore, that is what many of its framers thought.’

The main danger of a fresh constitution is that it fails to endow the new rulers with sufficient authority. Too often, political distrust means that the new government is hemmed in with restrictions, limiting its effectiveness. The Italian constitution of 1948 illustrates this problem with its hallmark of garantismo, meaning that all political forces are guaranteed a stake in the political system. It established a strong bicameral legislature and provided for regional autonomy, while trying to prevent a recurrence of fascist dictatorship and to accommodate the radical aspirations of the political left.The result was ineffective governance.

The durability of constitutions

In assessing the practical worth of constitutions, it is tempting to look at their age.The most impressive such documents, it might seem, are those that have lasted the longest. Conversely, a state that keeps changing its constitution is clearly experiencing difficulty in securing a stable framework of governance. In this sense, the United States – which adopted its constitution in 1789 – stands in contrast to Haiti, which drew up its first constitution shortly after independence in 1804, and adopted its 23rd and latest constitution in 1987. More important than age, however, is the question of quality. All constitutions contain a degree of idealism, and make claims that either cannot objectively be measured, or else are not reflected in reality. But how can we measure the quality of a constitution? At least in part, the answer lies in determining the size of the gap between what it says and what happens in practice.

The Mexican constitution, for example, was both radical and progressive from the time it was adopted in 1917: it contains principles that prohibit discrimination of any kind, provide for free education, establish the equality of men and women, limit the working day to eight hours, and prohibit vigilante justice. But many Mexicans argue that too many of its goals have not been met in practice, and thus they consider the constitution to be a work in progress. Matters are complicated by the ease with which it can be amended, requiring the support of only two-thirds of members of Congress and a majority of state legislatures. The result is that Mexican leaders will propose constitutional amendments even for minor matters: a package of electoral reforms in August 1996 alone involved 18 amendments. The constitution of India offers another example of the gap between goals and practice; its 448 articles guide the world’s largest democracy, and yet India suffers massive poverty, widespread corruption, human rights abuses (particularly in regard to women), unequal access to education, and an extraordinarily slow-moving legal process.

FIGURE 7.2: Ten facts about constitutions

Source: Based on information in Comparative Constitutions Project (2015)

Recent developments in the United States offer additional insights into the problem. The US constitution did not change after the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, but the detention of alleged terrorist in Guantanamo Bay and revelations about the use of torture and the increased monitoring by government agencies of phone and electronic communications raised troubling questions about the health of individual rights in the United States. It is often said that truth is the first casualty of war; in a similar vein, it is often the case with countries facing external threats that the rule of law takes second place to national security, and needs to be rebuilt subsequently through the courts.

Times, needs, and expectations change, and constitutions should change with them, up to a point. So while there should always be allowances for amendments, the procedures involved have critical implications: too many amendments can result in instability, while too few can result in stagnation. Here we meet the matter of entrenchment, a term referring to procedures which set a higher level and wider spread of support for amendments than is the case for ordinary legislative bills.

In the case of rigid constitutions, change is more difficult, usually demanding super- or concurrent majorities (see Figure 7.3). In the case of a flexible constitution, changes can be made more easily. Rigidity offers the general benefit of a stable political framework, and benefits rulers by limiting the damage should political opponents obtain power, because they would face the same barriers to change. On the other hand, non-entrenchment (which is rare) offers the advantage of ready adaptability. In New Zealand, this flexibility allowed changes to the electoral system and government administration in the 1980s and 1990s, while in the United Kingdom it allowed the devolution of significant powers to Scotland and Wales in 1999 without much constitutional fuss.

The most extreme form of entrenchment is a clause that cannot be amended at all. For example, the French and Turkish constitutions guarantee the republican character of their regimes. These statements set out to enforce a break with the old regime, but they also provide ammunition to those who see constitutions as the dictatorship of the dead over the living. In new conditions, past solutions sometimes have a way of turning into current problems.

A key element of the amendment procedure concerns the role of the legislature. On the one hand, some constitutions can be amended simply through special majorities within the legislature, thereby reducing the relative status of the constitution. This approach is found in European states with a strong commitment to parliamentary supremacy, such as Germany: amendments there (where permitted at all) require only a two-thirds majority in both houses. On the other hand, where modifications cannot be approved by the legislature alone, the constitution stands supreme over the legislature. In Australia, for example, amendments must be endorsed not only by the national parliament, but also by a referendum achieving a concurrent majority in most states and in the country as a whole.

Changes can also be initiated by other means than a formal amendment. The most important of these devices are judicial interpretation (the rulings of constitutional courts), and the passage of new laws that modify some aspect of the rules of government. And even when constitutions are codified, simple customs and traditions should not be forgotten; there is often much about the structure of government that is not written down, but has simply become a tradition. Political parties play a critical role in government all over the world, for example, but there may not always be much said about them in constitutions.

FIGURE 7.3: Comparing constitutional amendments

Notes:

Germany: The federal, social, and democratic character of the German state, and the rights of individuals within it, cannot be amended.

India: Selected amendments, such as those changing the representation of states in parliament, must also be approved by at least half the states.

Sweden: Has four fundamental laws which comprise its ‘constitution’. These include its Instrument of Government and Freedom of the Press Act.

United States: An alternative method, based on a special convention called by the states and by Congress, has not been used.

The role of courts

Constitutions are neither self-made nor self-implementing, and they need the support of institutions that can enforce their provisions by striking down offending laws and practices. This role has fallen to the judiciary; with their power of judicial review (allowing them to override decisions and the laws produced by governments), judges occupy a unique position in and above politics. They constrain the power of elected rulers, thereby both stabilizing and limiting democracy. Hirschl (2008: 119) has gone so far as to refer to the rise of juristocracy, or government by judges:

Entrenchment: The existence of special legal procedures for amending a constitution.

Rigid constitution: One that is entrenched, requiring more demanding amendment procedures.

Flexible constitution: One that can be amended more easily, often in the same way that ordinary legislation is passed.

Armed with judicial review procedures, national high courts worldwide have been frequently asked to resolve a range of issues, varying from the scope of expression and religious liberties, equality rights, privacy, and reproductive freedoms, to public policies pertaining to criminal justice, property, trade, and commerce, education, immigration, labor, and environmental protection.

Judicial review: The power of courts to nullify any laws or actions by government officials that contravene the constitution.

The function of judicial review can be allocated in one of two ways.The first and more traditional method – used in the United States and much of Latin America – is for the highest or supreme court in the ordinary judicial system to take on the task of constitutional protection. A supreme court rules on constitutional matters, just as it has the final say on other questions of common and statute law.A second and more recent method – favoured in Europe – is to create a special constitutional court, standing apart from the ordinary judicial system.

Supreme courts

As the name implies, a supreme court is the highest court within a jurisdiction, whose decisions are not subject to review by any other court. They are usually the final court of appeal, listening – if they choose – to cases appealed from a lower level. They also mainly use concrete review, meaning that they ask whether, given the facts of the particular case, the decision reached at lower level was compatible with the constitution. By contrast, constitutional courts mainly practise abstract review, judging the intrinsic constitutional validity of a law without limiting themselves to the particular case. In addition, constitutional courts can issue advisory judgments on a bill at the request of the government or assembly, often without the stimulus of a specific case at all. These latter judgments are often short and are usually unsigned, lacking the legal argument used by supreme courts. So concrete review provides decisions on cases with constitutional implications, while abstract review is a more general assessment of the constitutional validity of a law or bill. (Some courts, such as those in Ireland and Germany, use both concrete and abstract review.)

Concrete review: Judgments made on the constitutional validity of law in the context of a specific case.

Abstract review: An advisory but binding opinion on a proposed law, based on a suspicion of inconsistency with a constitution.

Confusingly, the name of a given court does not always follow its function. Hence the supreme courts of Australia and Hong Kong go under the title of High Court, those of France and Belgium under the title Cour de Cassation (Court of Appeal), and that of the European Union is the European Court of Justice, while a number of European countries – including Spain – have supreme courts whose decisions (some or all) can be appealed to constitutional courts.

The United States is the prototypical case of concrete review. The US constitution vests judicial power ‘in one Supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain’. Although the Court possesses original jurisdiction over cases to which a US state or a representative of another country is a party, its main role is appellate. That is, constitutional issues can be raised at any point in the ordinary judicial system and the Supreme Court selects only those cases that it believes raise significant constitutional questions; the vast majority of petitions for the Court to review a case are turned down.

Original jurisdiction: This entitles a court to try a case at its first instance.

Appellate: The power of a court to review decisions reached by lower courts.

Constitutional courts

This approach was born with the Austrian constitution of 1920, and became established in continental Europe after the Second World War. The success of Germany’s Federal Constitutional Court encouraged non-European countries to follow suit, such that nearly half the world’s states had such a court by 2005 (Horowitz, 2006). As with the constitutions they nurture, these courts represented a general attempt to prevent a revival of dictatorship; in the case of new democracies, constitutional courts have been created separately from the ordinary judicial system to help overcome the inefficiency, corruption, and opposition of judges from the old order.

TABLE 7.1: Comparing supreme courts and constitutional courts

| Supreme court | Constitutional court | |

| Form of review | Primarily concrete | Primarily abstract |

| Relationship to other courts | Highest court of appeal | A separate body dealing with constitutional issues only |

| Recruitment | Legal expertise plus political approval | Political criteria more important |

| Normal tenure | Until retirement | Typically one non-renewable term (6–9 years) |

| Examples | Australia, Canada, United States | Austria, Germany, Russia |

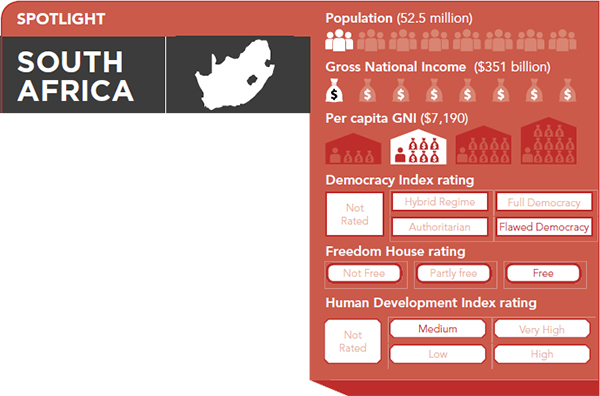

Brief Profile: South Africa languished for many decades under a system of institutionalized racial separation known as apartheid. This ensured privileges and opportunities for white South Africans at the expense of black, mixed race, and Asian South Africans. In the face of growing resistance, and ostracism from much of the outside world, an agreement was reached that paved the way for the first democratic elections in 1994. Much was originally expected from a country with a wealth of natural resources and the African National Congress has since won majorities at every election. Yet corruption is a growing problem, unemployment remains stubbornly high, many still live in poverty, and South Africa faces major public security challenges: it has one of the highest per capita homicide and violent assault rates in the world. Despite being the second largest economy in Africa (after Nigeria), it has only partly realized its potential as a major regional power.

Form of government  Unitary parliamentary republic. State formed 1910, and most recent constitution adopted 1997.

Unitary parliamentary republic. State formed 1910, and most recent constitution adopted 1997.

Legislature  Bicameral Parliament: lower National Assembly (400 members) elected for renewable five-year terms, and upper National Council of Provinces with 90 members, ten appointed from each of the nine provinces.

Bicameral Parliament: lower National Assembly (400 members) elected for renewable five-year terms, and upper National Council of Provinces with 90 members, ten appointed from each of the nine provinces.

Executive  Presidential. A president heads both the state and the government, ruling with a cabinet. The National Assembly elects the president after each general election. Presidents limited to two five-year terms.

Presidential. A president heads both the state and the government, ruling with a cabinet. The National Assembly elects the president after each general election. Presidents limited to two five-year terms.

Judiciary  The legal system mixes common and civil law. The Constitutional Court decides constitutional matters and can strike down legislation. It has 11 members appointed by the president for terms of 12 years.

The legal system mixes common and civil law. The Constitutional Court decides constitutional matters and can strike down legislation. It has 11 members appointed by the president for terms of 12 years.

Electoral system  The National Assembly is elected by proportional representation using closed party lists; half are elected from a national list and half from provincial lists.

The National Assembly is elected by proportional representation using closed party lists; half are elected from a national list and half from provincial lists.

Parties  Dominant party. The African National Congress (ANC) has dominated since the first full democratic and multiracial election in 1994. The more liberal Democratic Alliance, now the leading party in the Western Cape, forms the official opposition.

Dominant party. The African National Congress (ANC) has dominated since the first full democratic and multiracial election in 1994. The more liberal Democratic Alliance, now the leading party in the Western Cape, forms the official opposition.

Where a supreme court is a judicial body making the final ruling on all appeals (not all of which involve the constitution), a constitutional court is more akin to an additional legislative chamber. Hans Kelsen (1881–1973), the Austrian inventor of constitutional courts, argued that such courts should function as a negative legislator, striking down unconstitutional bills but leaving positive legislation to parliament. In this system, ordinary courts are not empowered to engage in judicial review, with appeals to the supreme court; instead, the review function is exclusive to a separate constitutional authority. This approach is more political, flexible, and less legal than is the case with supreme courts.

The constitution and courts in South Africa

South Africa’s transformation from a militarized state based on apartheid (institutionalized racial segregation) to a more constitutional order based on democracy was one of the most remarkable political transitions of the late twentieth century. What was the nature of the political order established by the new constitution?

In 1996, after two years of hard bargaining between the African National Congress (ANC) and the white National Party (NP), agreement was reached on a new 109-page constitution to take full effect in 1997. The NP expressed general support despite reservations that led to its withdrawal from government.

In a phrase reminiscent of the US constitution, South Africa’s constitution declares that ‘the Executive power of the Republic vests in the President’. As in the United States, the president is also head of state. Unlike the United States, though, presidents are elected by the National Assembly after each general election. They can be removed through a vote of no confidence in the assembly (though this event would trigger a general election), and by impeachment. The president governs in conjunction with a large cabinet.

Each of the country’s nine provinces elects its own legislature and forms its own executive headed by a premier. But far more than in the United States, authority and funds flow from the top down. In any case, the ANC provides the glue linking not only executive and legislature, but also national, provincial, and municipal levels of government. So far, at least, the ruling party has dominated the governing institutions, whereas in the United States, the institutions have dominated the parties.

South Africa’s rainbow nation faces some difficulties in reconciling constitutional liberal democracy with the political dominance of the ANC. The modest reduction in the size of the ANC’s parliamentary majority in the 2009 elections exerted a moderating effect, reducing the ANC’s desire and capacity to amend the constitution in its favour. But the country’s politics, more than most, should be judged by what preceded it. By that test the achievements of the new South Africa are remarkable indeed.

Germany has become the exemplar of the constitutional court approach. Its Federal Constitutional Court (FCC) has the following powers: judicial review, adjudication of disputes between state and federal political institutions, protection of individual rights, and protection of the constitutional and democratic order against groups and individuals seeking to overthrow it (Conradt, 2008: 253). The ‘eternity clause’ in the Basic Law means that the FCC’s judgments in key areas of democracy, federalism and human rights are absolutely the final word. (The term basic law, used in Germany in place of constitution, implies a temporary quality that makes it different from an entrenched constitution. In spite of this, the two are functional equivalents. Other countries using the term basic law include Hong Kong, Israel, and Saudi Arabia.)

The FCC consists of 16 members appointed by the legislature for a non-renewable term of 12 years. The Court is divided into two specialized chambers, of which one focuses on the core liberties enshrined in the Basic Law. The Court’s public reputation has been enhanced by the provision of constitutional com-plaint, an innovative device allowing citizens to petition the Court directly once other judicial remedies are exhausted.

The Court actively pursued its duty of maintaining the new order against groups seeking its over-throw; for instance, by banning both communist and neo-Nazi parties in the 1950s. For this reason, Kommers (2006) describes the Court as ‘the guardian of German democracy’. It has continued in this role by casting a careful eye on whether European Union laws and policies detract from the autonomy of the country’s legislature.The Court has also been active on policy topics as varied as abortion, election procedures, immigration, party funding, religion in schools, and university reform.

Judicial activism

Perhaps with the exception of Scandinavia, judicial intervention in public policy has grown throughout the liberal democratic world since 1945, marking a transition from judicial restraint to judicial activism. For Hirschl (2008: 119), this is one of the most significant phenomena of government in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Judges have become more willing to enter political arenas that would have once been left to elected politicians and national parliaments; for instance:

• India’s Supreme Court has ‘appointed itself as the guardian of vulnerable social groups and neglected areas of public life, such as the environment’ (Mitra, 2014: 587).

• Israel’s Supreme Court addressed such controversial issues as the West Bank barrier, the use of torture in investigations by the security service, and the assassination of suspected terrorists (Hirschl, 2008).

• The US Supreme Court decided the outcome of the 2000 presidential election by voting along party lines that George W. Bush had won the election in the state of Florida, and thus the presidential election. One commentator controversially described the vote as ‘the single most corrupt decision in Supreme Court history’ and ‘a violation of the judicial oath’ because the majority decided on the basis of ‘the personal identity and political affiliation of the litigants’ (Dershowitz, 2001: 174 and 198).

Judicial restraint: The view that judges should apply the letter of the law, leaving politics to elected bodies.

Judicial activism: The willingness of judges to venture beyond narrow legal reasoning so as to influence public policy.

There are four key reasons for the drift from restraint to activism:

• The decline of the political left has enlarged the scope of the judiciary. Socialists were once suspicious of judges, believing them to be unelected defenders of the status quo, and of property specifically. The left has since discovered in opposition that the courtroom can be a venue for harassing governments of the right.

• The increasing reliance on regulation as a mode of governance encourages court intervention. A government decision to deny gay partners the same rights as married couples is open to judicial challenge in a way that a decision to go to war or raise taxes is not.

• International conventions give judges an extra lever to move outside the limits of national law. Documents such as the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the European Convention on Human Rights provide a base on which judges can construct what would once have been viewed as excessively political statements. The emergence of international courts such as the International Criminal Court (founded in 2002) has also encouraged national courts to become more assertive.

• The continuing prestige of the judiciary encouraged some transfer of authority to its domain.The judicial process in most liberal democracies has retained at least some reputation for integrity and impartiality, whereas the standing of many other institutions – notably political parties – has declined.

Whatever the factors lying behind the expansion of judicial authority, the process seems to reinforce itself. Stone Sweet (2000: 55) makes the point that ‘as constitutional law expands to more and more policy areas, and as it becomes “thicker” in each domain, so do the grounds for judicialized debate. The process tends to reinforce itself.’ Sensing the growing confidence of judges in addressing broader political issues, interest groups, rights-conscious citizens, and even political parties have become more willing to continue their struggles in the judicial arena.

Of course, judicial activism has gone further in some democracies than in others, few states having taken it further than the United States. The US is founded on a constitutional contract and an army of lawyers forever quibbles over the terms. Armed with a written constitution, federalism, judicial independence, no system of separate administrative courts, a legal system based on judge-made case law, and high esteem for judges, the US has moved ever further into a culture of judicial activism. The influence of the US Supreme Court on American public policy has led one critic of ‘government by judges’ to dismiss it as ‘a nine-man, black-robed junta’ (Waldron, 2007: 309).

Fewer conditions of judicial autonomy are met in Britain, where parliamentary sovereignty long reigned supreme. Lacking the authority to annul legislation, judicial review in the British context normally refers to the capacity of judges to review executive decisions against the template provided by administrative law. Even so, judicial activism has grown in Britain, reflecting European influence. British judges were willing accomplices of the European Court of Justice as it established a legal order applying to all member states. Judicial assertiveness was further encouraged by the country’s belated adoption of the European Convention on Human Rights in 1998, the decay of the royal prerogative which once allowed the state to stand above the law, and the establishment of a British Supreme Court in 2009.

Formal statements of rights have also encouraged judicial expansion in other English-speaking countries. In Canada, a Charter of Rights and Freedoms was appended to the constitution in 1982, giving judges a more prominent role in defending individual rights. Similarly, New Zealand introduced a bill of rights in 1990, protecting ‘the life and security of the person’ and also confirming traditional, but previously uncodified, democratic and civil rights.

Judicial independence and recruitment

Given the growing political authority of the judiciary, the question of maintaining its independence gains in importance. Liberal democracies accept judicial autonomy as fundamental to the rule of law, but how is this independence achieved in practice? Security of tenure is important, which is why it is hard to remove them during their terms in office. But judicial autonomy also depends on how they are recruited. Were the selection of judges on the highest court to be controlled by politicians, the judiciary would simply reinforce partisan authority, providing an integration (rather than a separation) of powers. This danger is particularly acute when judicial tenure is short, limiting the period in which judges can develop their own perspective on the cases before them.

As a result, governments have developed multiple solutions to the issue of judicial selection, ranging from democratic election to co-option by judges already in post (see Figure 7.4). The former is democratic but political, while the latter offers the surest guarantee of independence but can lead to a self-perpetuating elite because it runs the danger that the existing judges will seek out new recruits with an outlook resembling their own. In between these extremes come the more conventional methods: appointment by the legislature, by the executive, and by independent panels. Many countries combine these orthodox methods, with the government choosing from a pool of candidates prepared by a professional body. Alternatively, and more traditionally, some judges on the senior court can be selected by one method, while others are chosen by a different method.

The British government recently ceded power of appointment to an independent commission, a decision justified by the relevant minister in the following way:

In a modern democratic society it is no longer acceptable for judicial appointments to be entirely in the hands of a Government Minister. For example the judiciary is often involved in adjudicating on the lawfulness of actions of the Executive. And so the appointments system must be, and must be seen to be, independent of Government. It must be transparent. It must be accountable. And it must inspire public confidence. (Falconer, 2003: 3–4)

For most courts charged with judicial review, selection still involves a clear political dimension. For example, the stature of the US Supreme Court combines with the unusual rule of lifetime appointments to make sure that nominations are key decisions. In these contests, the judicial experience and legal ability of the nominee may matter less than ideology, partisanship, and a clean personal history. Even so, Walter Dellinger, former acting US Solicitor General, argues that ‘the political appointment of judges is an appropriate “democratic moment” before the independence of life tenure sets in’ (Peretti, 2001).

A political dimension is also apparent in selection to constitutional courts. Typically, members are selected by the legislature in a procedure that can involve party horse-trading. For instance, 8 out of the 12 members of Spain’s Constitutional Court are appointed by the party-dominated parliament.

FIGURE 7.4: Comparing judicial appointments

Below the level of the highest court, judicial autonomy raises the issue of internal independence. The judiciary is more than the highest court of the land; it is an elaborate, multi-tiered structure encompassing ordinary courts, appeal courts, and special bodies such as tax and military courts. Whether justices at lower levels are inhibited or empowered shapes the effectiveness of the judicial system as a whole in resolving conflicts in a fair, effective and predictable fashion.

Internal independence: Refers to the autonomy of junior judges from their senior colleagues, who often determine career advancement.Where this autonomy is limited, judicial initiative may be stifled.

Guarnieri (2003: 225) emphasizes the importance of internal independence. Noting that ‘judicial organizations in continental Europe traditionally operate within a pyramid-like organizational structure’, he argues that ‘the role played by organizational hierarchies is crucial in order to highlight the actual dynamics of the judicial corps’. This issue arose in acute form in some continental European countries after 1945, when judges appointed under right-wing regimes continued in post, discouraging initiatives by new recruits lower in the pyramid. Guarnieri concludes that promotion and salary progression within the judiciary should depend solely on seniority, noting that such reforms were needed in Italy before younger ‘assault judges’ became willing to launch investigations into government corruption. This blanket solution may be extreme but it is important to recognize that the decisions of judges lower in the hierarchy will be influenced by anticipated effects on their career prospects.

Because senior judges are such key actors in shaping government, it is important to ask how they go about reaching their decisions. Three explanatory models have been developed:

• Legal: This is the most traditional, and assumes that judges are driven in their decisions by an understanding of the law. Of course, the fact that an issue has reached the highest court means that it is legally uncertain, so the law itself is not wholly determining. Even so, judges are likely to bear in mind precedent, legal principles, and the implications of their judgment for the future development of the law. They can hardly reach a particular decision unless they can wrap it in at least some legal covering.

• Attitudinal: This assumes that judges are driven by politics and ideology. The US Supreme Court is a primary example, because its verdicts are given in the form of unanimous or majority opinions, with dissenting opinions often also produced, and it is known how each of the justices voted. These open procedures allow researchers to assess whether, across a series of cases, a particular justice can be classified as consistently liberal or conservative, and to relate their ideological profile to such factors as the justice’s social background. The answer is usually quite clear, which is why appointments to the US court generate so much public interest, and the likely outcome of votes can be anticipated well in advance.

• Strategic: This regards judges as sensitive to the likely reactions of other political actors and institutions to their pronouncements. As with any other institution, the highest courts (and often lower ones, too) act to maintain their standing, autonomy, and impact. Accordingly, judges will think hard before courting controversy or making decisions that will be ignored, or even reversed through constitutional amendment. This strategic model invites us to think of judges on the highest court as full players in the game of elite politics, who must abide by the rule of anticipated reactions. Germany’s constitutional court is an example, concerned as it is to sustain democracy by defending the autonomy of its country’s legislature.

Systems of law

As well as understanding constitutions and courts, it is also important to understand systems of law. The two most important of these are common law and civil law, whose contrasting principles are essential to an appreciation of the differences in the political role of judiciaries everywhere outside the Middle East. The third is sharia law, found in most Muslim countries, and even coexisting with common or civil law in countries with large Muslim populations, such as Nigeria, or in countries with a colonial history, such as Egypt.

Common law

The key feature of common law systems is that the decisions made by judges on specific cases form an overall legal framework which remains distinct from the authority of the state. It is found mainly in Britain and in countries that were once British colonies, such as Australia, Canada (except Quebec), India, Kenya, Nigeria, Pakistan, and the United States (except Louisiana). Originally based on custom and tradition, such decisions were first published as a way of standardizing legal judgments across the territory of a state. Because judges abided by the principle of stare decisis (stand on decided cases), their verdicts created precedents and established a predictable legal framework, contributing thereby to economic exchange and nation-building.

Where common law is judge-made law, statute law is passed by the legislature in specific areas but these statutes usually build on case law (the past decisions of courts) and are themselves refined through judicial interpretation. The political significance of common law systems is that judges constitute an independent source of authority. They form part of the governance, but not the government, of society. In this way, common law systems contribute to political pluralism.

Common law: Judicial rulings on matters not explicitly treated in legislation, based on precedents created by decisions in specific cases.

Statute law: Laws enacted by a legislature.

Civil law: Judicial rulings founded on written legal codes which seek to provide a single overarching framework for the conduct of public affairs.

Civil law

Civil law springs from written legal codes rather than cases, the goal being to provide a single framework for the conduct of public affairs, including public administration and business contracts. The original codes were developed under Justinian, Roman emperor between 527 and 565.This system of Roman law has evolved into distinct civil codes, which are then elaborated through laws passed by the national legislatures. Civil law is found throughout Latin America, in all of continental Europe, in China and Russia, and in most African countries that were once colonies of continental European powers.

In civil law, judges (rather than juries) identify the facts of the case, and often even direct the investigation. They then apply the relevant section of the code to the matter at hand. The political importance of this point is that judges are viewed as impartial officers of state, engaged in an administrative task; they are merely la bouche de la loi (the mouth of the law).The courtroom is a government space, rather than a sphere of independent authority; judge-made law would be viewed as a threat to legislative supremacy.

The underlying codes in civil law systems often emphasize social stability as much as individual rights. The philosophy is one of state-led integration, rather than pluralism. Indeed, the codes traditionally functioned as a kind of extensive constitution, systematically setting out obligations as well as freedoms. However, the more recent introduction of distinct constitutions (which have established a strong position in relation to the codes) has strengthened the liberal theme in many civil law countries. In addition, judges have inevitably found themselves filling gaps in the codes, providing decisions which function as case law, even though they are not acknowledged as such. These developments dilute, without denying, the contrast between civil law and common law (Stone Sweet, 2000).

Religious law

In reviewing different legal systems, it is important not to overlook those that are related to religion: Islam, Juda-ism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and the Catholic Church all have their own distinctive bodies of law, some of which remain important in regulating the societies in which they are found. Some states, such as Bangladesh, also have polycentric legal systems that include separate provisions for different religions. Of all such religious legal systems, the one that has attracted the most international attention – and the one that is most widely misunderstood – is the sharia law of Muslim states.

Sharia law: The system of Islamic law – based on the Quran and on the teachings and actions of Muhammad – which functions alongside Western law in most Islamic states.

In the West, Islamic law tends to come to attention only when someone has been sentenced to be stoned to death for adultery, or in the context of the unequal treatment of women in many Muslim societies. The result is a misleading conception of how it works, and an unfortunate failure to understand that Islamic law is deep and sophisticated, with its own courts, legal experts, and judges and its own tradition of jurispru-dence (see Hallaq, 2007 for a survey). At the same time, however, while the use of Islamic law is one of the ideals of an Islamic republic, sharia law is not universally applied in any. It is widely used in Iran, Jordan, Libya, Mauritania, Oman, and Saudi Arabia, but most Islamic states use a mix of common or civil law and Islamic religious law, turning to the former for serious crime and to the latter for family issues.

Unlike Western law, where lawbreakers must account only to the legal system, the Islamic tradition holds that lawbreakers must account to Allah and all other Muslims. Also unlike Western law, the sharia outlines not only what is forbidden for Muslims but also what is discouraged, recommended, and obligatory. So, for example, Muslims should not drink alcohol, gam-ble, steal, commit adultery, or commit suicide, but they should pray every day, give to charity, be polite to others, dress inoffensively, and – when they die – be bur-ied in anonymous graves. When Muslims have doubts about whether something they are considering doing is acceptable, they are encouraged to speak to a Muslim judge, called a mufti, who will issue a legal judgment known as a fatwa.

Constitutions and courts in authoritarian states

The nature of authoritarian regimes is such that restraints on rule go unacknowledged, and power, not law, is the political currency. Constitutions are weak, and the formal status of the judiciary is similarly reduced. In fact, it is often only in the transition to democracy that the old elite empowers the courts, seeking guarantees for its own diminished future (Solomon, 2007). In instances where courts do have power, it tends to be only because authoritarian leaders use them to further their control.

Non-democratic rulers follow two broad strategies in limiting judicial authority. One is to retain a framework of law and a facade of judicial independence, but to influence the judges indirectly through recruitment, training, evaluation, promotion, and disciplinary procedures. In the more determined cases, they can simply be dismissed. Egypt’s President Nasser adopted this strategy with vigour in 1969 when he fired 200 in one fell swoop in the ‘massacre of the judges’. Uganda’s notorious military dictator Idi Amin adopted the ultimate form of control in 1971 when he had his chief justice shot dead.

A second more subtle strategy is to bypass the judicial process. For instance, many non-democratic regimes use Declarations of Emergency as a cover to make decisions which are exempt from judicial scrutiny. In effect, a law is passed saying there is no law. Once introduced, such ‘temporary’ emergencies can drag on for decades. Alternatively, rulers can make use of special courts that do the regime’s bidding without much pretence of judicial independence; Egypt’s State Security Courts were an example, hearing matters involving ‘threats’ to ‘security’ (a concept that was interpreted broadly) until they were closed down in 2008. Military rulers have frequently extended the scope of secret military courts to include civilian troublemakers. Ordinary courts can thus continue to deal with non-political cases, offering a thin image of legal integrity to the world.

Under the circumstances, it is little surprise that authoritarian regimes have a poor record on human rights. Comparative data in this area lack the established record of the indices we have reviewed for democracy and corruption. One index that has generated data since 1981, but has not been published since 2011, is the CIRI Human Rights Data Project, which used information from the US State Department on human rights in countries around the world, including their records on free speech, freedom of movement, execution, torture, disappearances, and political imprisonment. The project gave scores ranging downward from 30; in 2010, the world average was 18, Denmark and Iceland scored 30 and the United States ranked fifth equal with 26.The ten countries with the lowest scores are shown in Table 7.2.

As Table 7.2 suggests, one state with an extended history of human rights abuses is Zimbabwe, which has languished under the government of Robert Mugabe since independence in 1980. Following a period of growing political conflict and economic decline, a new constitution was adopted in 2013, offering hope that life for Zimbabweans might become more secure. But the governing party ZANU-PF – which won nearly three-quarters of the seats in the legislature in deeply flawed 2013 elections – dragged its feet in implementing the provisions of the constitution and in amending existing laws restricting freedom of expression and assembly. Media and academic freedom remain limited,opponents of the regime are still routinely harassed, property rights are ignored, the military is used to support the regime, and the courts are manipulated to suit Mugabe’s purposes. For example, the courts ruled the 2013 elections to be free and fair in spite of clear evidence to the contrary.

TABLE 7.2: The ten countries with the lowest scores on human rights

In states with a ruling party, courts are viewed not as a constraint upon political authority but as an aid to the party in its policy goals. China is currently on its fourth and most recent constitution (dating from 1982), and even though it begins by affirming the country’s socialist status, and warning against ‘sabotage of the socialist system’ it is the least radical of the four. It seeks to establish a more predictable environment for economic development and to limit the communist party’s historic emphasis on class conflict, national self-reliance, and revolutionary struggle.The leading role of the party is now mentioned only in the preamble, with the main text even declaring that ‘all political parties must abide by the Constitution’. Amendments in 2004 gave further support to private property and human rights. In the context of communist states, such liberal statements are remarkable, even if they remain a poor guide to reality.

In addition to moderating the content of its constitution, today’s China also gives greater emphasis to law in general. There were very few laws at all in the early decades of the People’s Republic, reflecting a national tradition of unregulated power, and leaving the judiciary as, essentially, a branch of the police. However, laws did become more numerous, precise, and significant after the hiatus of the Cultural Revolution (1966–76). In 1979, the country passed its first criminal laws; later revisions abolished the vague crime of counter-revolution and established the right of defendants to seek counsel. Law could prevail to the benefit of economic development. For law-abiding citizens, life became more predictable.

Despite such changes, Chinese politics remains authoritarian. ‘Rule by law’ still means exerting political control through law, rather than limiting the exercise of power. The courts are regarded as just one bureaucratic agency among others, legal judgments are not tested against the constitution, and many decisions are simply ignored. Rulings are unpublished and difficult cases are often left undecided. In comparison with liberal democracies, legal institutions remain less specialized, and legal personnel less sophisticated. Trial procedures, while improving, still offer only limited protection for the innocent. The death penalty remains in use, the police remain largely unaccountable, political opponents are still imprisoned without trial, and party officials continue to occupy a protected position above the law. Because the party still rules, power continues to trump the constitution and human rights.

Iran offers a further case of a legal system operating in the context of an authoritarian regime. To be sure, the country exhibits all the trappings of a constitution supported by a court system. The constitutional document makes noble statements about an Islamic Republic ‘endorsed by the people of Iran on the basis of their long-standing belief in the sovereignty of truth and Quranic justice’, and about the ‘exalted dignity and value of man’ and the independence of the judiciary. But Iran has one of the weaker records on human rights in the world. Many activists languish in jail on political charges, Iran has a rate of execution that is probably second only to that of China (there are many capital offences in Iran, include apostasy (abandon-ment of Islam) and moharebeh (‘enmity against God’)), and women and minorities face discrimination of many kinds. In contrast to Western states, the constitution expresses Islamic more than liberal values and the court system is a channel rather than a limitation on power.

In hybrid or competitive authoritarian regimes, too, constitutions and the law are subsidiary to political authority. The leader may be elected within a constitutional framework, but that environment has been shaped by the leader, and the exercise of power is rarely constrained by an independent judiciary. Presidents occupy the highest ground, defining the national interest under the broad authority granted to them by the voters. In other words, presidential accountability is vertical (to the voters) rather than horizontal (to the judiciary). In contrast to a liberal democracy, where the main parties have concluded that being ruled by law is preferable to being ruled by opponents, under competitive authoritarianism the commanding figure still sees the constitution, the law, and the courts as a source of political advantage. Legal processes operate more extensively than in pure authoritarian regimes but remain subject to political manipulation.

The Russian experience shows that law can gain ground – if only slowly and with difficulty – in at least some authoritarian regimes. Russia’s post-communist constitution of 1993 set out an array of individual rights (including that of owning property); proclaimed that ‘the individual and his rights and freedoms are the supreme value’; and established a tripartite system of general, commercial, and constitutional courts. The Constitutional Court, in particular, represented a major innovation in Russian legal thinking.

Since 1993, the government has established detailed and lengthy (if not always well-drafted) codes appropriate for a civil law system. From 1998, criminal defendants who have exhausted all domestic remedies have even been able to appeal to the European Court of Human Rights (Sharlet, 2005: 147). More prosaically, tax law and business law have been modernized.

But in Russia, as in other authoritarian regimes (and even some liberal democracies),‘there has been and remains a considerable gap between individual rights on paper and their realization in practice’ (Sharlet, 2005: 134). For instance:

• The conviction rate in criminal cases remains suspi-ciously high.

• Expertise and pay within the legal system are low, sustaining a culture of corruption.

• Violence by the police is common.

• Politics overwhelms the law on sensitive cases (such as the imprisonment in 2005 of business oligarch, Mikhail Khodorkovsky).

• Legal judgments, especially against the state, can be difficult to enforce.

• The public still shows little faith in the legal system (Smith, 2010: 150).

So, Russia has made more progress towards achieving the rule of law than has China, but assuming that law in Russia will eventually acquire the status it possesses in liberal democracies still involves drawing a cheque against the future. Smith (2010: 135) concedes that much progress has been made in establishing ‘a workable and independent judiciary and legal system’, with new laws enacted and legal reforms undertaken, but notes that ‘the enforcement of laws has been uneven and at times politicised, which erodes public support and belief in the courts’.

• Which is best: a constitution that is short and ambiguous, leaving room for interpretation, or one that is long and detailed, leaving less room for misunderstanding?

• What are the advantages and disadvantages of codiêd and uncodiêd constitutions?

• What are the advantages and disadvantages of supreme courts against constitutional courts?

• Judicial restraint or judicial activism – which is best for the constitutional well-being of a state?

• What is the best way of recruiting judges, and what are the most desirable limits on their terms in o˚ ce, if any?

• Can religious and secular law coexist?

KEY CONCEPTS

Abstract review

Appellate

Civil law

Codified constitution

Common law

Concrete review

Constitution

Entrenchment

Flexible constitution

Internal independence

Judicial activism

Judicial restraint

Judicial review

Original jurisdiction

Rigid constitution

Rule of law

Sharia law

Statute law

Uncodified constitution

FURTHER READING

Guarnieri, Carlo and Patrizia Pederzoli (2002) The Power of Judges: A Comparative Study of Courts and Democracy. A cross-national study of the judiciary.

Harding, Andrew and Peter Leyland (eds) (2009) Constitutional Courts: A Comparative Study. A comparative study of constitutional courts, with cases from Europe, Russia, the Middle East, Latin America, and Asia.

Issacharoff, Samuel (2015) Fragile Democracies: Contested Power in the Era of Constitutional Courts. Argues that strong constitutional courts are a powerful antidote to authoritarianism, because they help protect against external threats and the domestic consolidation of power.

Lee, H. P. (2011) Judiciaries in Comparative Perspective. An edited collection of studies of judiciaries in Australia, Britain, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa, and the United States.

Sunstein, Cass (2001) Designing Democracy:What Constitutions Do. A provocative assessment of how constitutions can be used to constructively channel political divisions.

Toobin, Jeffrey (2009) The Nine: Inside the Secret World of the Supreme Court. A journalist looks at the workings of the US Supreme Court.