PREVIEW

The focus of this chapter is the most visible tier in any system of government: the top level of leadership.Whether we are talking about presidents, prime ministers, chancellors, dictators, or despots, those who sit at the peak of the pyramid of governmental power typically excite the most public interest, whether opinions are positive or negative.To be sure, executives – in democracies, at least – consist not just of individual leaders but of large networks of people and institutions, including the ministers and secretaries who form the cabinet or the council of ministers. But a single figure usually becomes the best-known face of government, representing its successes and failures and acting as a focus of popular attention.

The chapter begins by looking in turn at the three major forms of executive: presidential, parliamentary, and semi-presidential. It compares and contrasts their roles and powers, focusing in particular depth on the various sub-types of parliamentary executive and the experience they have had with legislative coalitions. The contrasting roles of head of state and head of government are also reviewed; they are combined in presidential systems and divided in others, with important and contrasting consequences. The chapter then looks at executives in authoritarian systems, and at the particular qualities and effects of personal rule. Authoritarian leaders may enjoy more power than their democratic peers, but they also enjoy fewer formal protections on their person or their tenure in office.This inevitably affects the way they approach their positions.

CONTENTS

• Executives: an overview

• Presidential executives

• Parliamentary executives

• Semi-presidential executives

• Executives in authoritarian states

KEY ARGUMENTS

| • The political executive is the top tier of government, responsible for setting priorities, mobilizing support, resolving crises, making decisions and overseeing their implementation. |

| • Executives take three main institutional forms: presidential, parliamentary, and semi-presidential. |

| • Studies of presidential executives routinely refer back to the somewhat atypical case of the United States. There is ongoing debate about the strengths and weaknesses of the presidential model. |

| • Parliamentary government is often studied through the British example, even if it is more accurately represented through the multi-party coalitions of continental Europe. The smaller countries, in particular, provide opportunities to address the origins, stability, and effectiveness of different types of coalition. |

| • Semi-presidential systems combine elements of the presidential and parliamentary formats (for example, there is both a president and a prime minister). They are less common, and less thoroughly studied. |

| • Executives in authoritarian states are particularly intriguing because they face fewer constraints than those in liberal democracies, as well as fewer guarantees regarding their tenure. |

Brief Profile: The recent rise of Brazil exemplifies the phenomenon of the emerging economy, and earned it inclusion in the informal cluster of BRIC states (Brazil, Russia, India, and China). As the world’s fifth biggest country by land and population, Brazil is one of the world’s largest democracies. It is the most important state in South America and has expanded its influence to the developing world more broadly. However, in common with the other BRIC states, Brazil still faces many domestic problems. There is a wide gap between rich and poor, much of the arable land is owned by a few wealthy families, social conditions in its major cities are poor, the deforestation of the Amazon basin has global ecological implications, and corruption is rife at all levels of government. Recent economic developments have sent mixed signals, with oil discoveries pointing to energy self-sufficiency, but an economic downturn and a return to politics as usual casts clouds over Brazil’s continued progress.

Form of government Federal presidential republic consisting of 26 states and a Federal District. State formed 1822, and most recent constitution adopted 1988.

Federal presidential republic consisting of 26 states and a Federal District. State formed 1822, and most recent constitution adopted 1988.

Legislature  Bicameral National Congress: lower Chamber of Deputies (513 members) elected for renewable four-year terms, and upper Senate (81 members) elected from the states (three members each) for renewable eight-year terms.

Bicameral National Congress: lower Chamber of Deputies (513 members) elected for renewable four-year terms, and upper Senate (81 members) elected from the states (three members each) for renewable eight-year terms.

Executive  Presidential. A president directly elected for no more than two consecutive four-year terms.

Presidential. A president directly elected for no more than two consecutive four-year terms.

Judiciary  A dual system of state and federal courts, with justices of superior courts nominated for life by the president and confirmed by the Senate. Supreme Federal Court serves as constitutional court: 11 members, nominated by president and confirmed by Senate for life, but must retire at 70.

A dual system of state and federal courts, with justices of superior courts nominated for life by the president and confirmed by the Senate. Supreme Federal Court serves as constitutional court: 11 members, nominated by president and confirmed by Senate for life, but must retire at 70.

Electoral system  A two-round majority system is used for elections to the presidency and the Senate, while elections to the Chamber of Deputies use proportional representation.

A two-round majority system is used for elections to the presidency and the Senate, while elections to the Chamber of Deputies use proportional representation.

Parties  Multi-party, with more than a dozen parties organized within Congress into four main coalitions and a cluster of non-attached parties.

Multi-party, with more than a dozen parties organized within Congress into four main coalitions and a cluster of non-attached parties.

Executives: an overview

The political executive is the core of government, consisting as it does of the political leaders who form the top level of the administration: presidents, prime ministers, ministers, and cabinets. The institutional approach to comparison focuses on the role of the executive as a government’s energizing force, setting priorities, mobilizing support, reacting to problems, resolving crises, making decisions, and overseeing their execution. Governing without an assembly or judiciary is feasible, but ruling without an executive is arguably impossible. And in authoritarian systems, the executive is often the only institution that wields true power.

The political executive in Brazil

The American model of the presidential executive is used in most Latin American countries, but often with local variations. Brazil is a case in point. On the one hand, its president would seem to be more powerful than the US equivalent, being able to issue decrees in specified areas, to declare bills to be urgent (forcing Congress to make a prompt decision), to initiate bills in Congress, and to propose a budget which goes into effect, month by month, if Congress does not itself pass a budget.

But Brazilian presidents must work with two features of government (proportional representation and a multi-party system) that are absent in the United States, and that make it more difficult to bend Congress to their will. First, they are faced by a much more complex party landscape. For example, the October 2014 legislative elections resulted in 28 parties winning seats in the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies: no party won more than 70 seats, 13 parties each won less than ten seats, and the parties formed themselves into four groupings, with the pro-government coalition holding 59 per cent of the seats.

To further complicate matters for the president, party discipline is exceptionally weak. Deputies often switch party in mid-term, and are more concerned with winning resources for their districts than with showing loyalty to their party (a reality also, but to a lesser extent, in the United States). In response, Brazil’s presidents build informal coalitions by appointing ministers from a range of parties in an attempt to extract loyalty from them.

The Brazilian case shows that the executive in presidential government does not need to be drawn from a single party. However, the coalitions they form are more informal, pragmatic, and unstable than the carefully crafted inter-party coalitions which characterize parliamentary government in Europe. In presidential systems, after all, the collapse of a coalition does not mean the fall of a government, reducing the incentive to sustain a coalition. So, although Latin American constitutions appear to give the chief executive a more important political role, appearances are deceptive. The Latin American experience confirms that presidents operating in a democratic setting confront inherent difficulties in securing their programme.

It is important to distinguish the political executive (which makes policy) from the bureaucracy (which puts policy into effect). Unlike appointed officials, the members of the executive – in democracies, at least – are chosen by political means, most often by election, and can be removed by the same method. The executive is accountable for the activities of government; it is where the buck stops.

It is also important to distinguish between two different roles carried out by executives: the head of state (the figurehead representative of the state and all its citizens) and the head of government (the political leader of a government). In presidential executives such as the United States, Mexico, and Nigeria, the two jobs are combined in one office. In parliamentary systems, the prime minister or chancellor is the head of government, while monarchs or non-executive presidents carry out the role of head of state. In semi-presidential systems, the division of roles – as we will see – is more complicated.

Head of state: The figurehead leader of a state, who may be elected or appointed, or – in the case of monarchs – may inherit the position.The role is non-political and has many functions but few substantive powers.

Head of government: The elected leader of a government, who comes to office because of the support of voters who identify with their party and platform.

In liberal democracies, understanding the executive begins with the study of institutional arrangements. Liberal democracies have succeeded in the delicate and difficult task of subjecting executive power to constitutional constraint. The government is not only elected, but remains subject to rules which limit its power; it must also face regular re-election.

In authoritarian regimes, by contrast, constitutional and electoral controls are absent or ineffective. The scope of the executive is limited not so much by the constitution as by political realities, and the executive tends to be more fluid, patterned by informal relationships rather than formal rules.

The executives of liberal democracies fall into three main groups: presidential, parliamentary, and semi-presidential. In all three types, power is diffused, and they can each be understood as contrasting methods for dividing and controlling executive authority. These arrangements can be tested against their contributions to political stability and effective governance. In presidential and semi-presidential regimes, the constitution sets up a system of checks and balances between distinct executive, legislative and judicial institutions. In parliamentary systems, the government is constrained in different ways, its survival depending on retaining the confidence of the assembly. Typically, its freedom of action is limited by the need to sustain a coalition between parties that have agreed to share the task of governing.

Presidential executives

The world contains many presidents but fewer examples of presidential government. This is in part because many parliamentary systems possess a president who serves only as ceremonial head of state, and in part because any dictator can style themselves ‘president’, and many do so. For these reasons, the existence of a president is an insufficient sign of a presidential system.

Presidential government: An arrangement in which power is divided between a president and a legislature.This distinction is achieved by separate elections and also by separate survival; the president cannot dissolve the legislature and the legislature can only remove the president through impeachment.

In essence, a presidential executive is a form of constitutional rule in which a single chief executive governs using the authority derived from popular election, alongside an independent legislature. The election normally takes the form of a direct vote of the people, with a limit on the number of terms a president can serve. The president directs the government and, unlike most prime ministers in parliamentary government, also serves as the ceremonial head of state. The president makes appointments to other key government institutions, such as the heads of government departments, although some may be subject to confirmation by the legislature. Because both president and legislature are elected for a fixed term, neither can bring down the other, giving each institution some autonomy.

Presidential executives have both strengths and weaknesses. Among the strengths:

• The president’s fixed term provides continuity in the executive, avoiding the collapse of governing coalitions to which parliamentary governments are prone.

• Winning a presidential election requires candidates to develop broad support across the country.

• Elected by the country at large, the president rises above the squabbles between local interests represented in the legislature.

• A president provides a natural symbol of national unity, offering a familiar face for domestic and international audiences alike.

• Since a presidential system necessarily involves a separation of powers, it should also encourage limited government and thereby protect liberty.

But presidential government also carries risks. Only one party can win the presidency; everyone else loses. All-or-nothing politics can lead to political instability, especially in new regimes. Fixed terms of office are inflexible, and the American experience shows that deadlock can arise when executive and legislature disagree, leaving the political system unable to address pressing problems. Presidential systems also lack the natural rallying-point for opposition provided by the leaders of non-ruling parties in some parliamentary systems. In particular, there is no natural equivalent to Britain’s notion of the Leader of Her Majesty’s Opposition.

TABLE 9.1: Presidential executives

• Elected president steers the government and makes senior appointments.

• Fixed terms of offices for the president and the legislature, neither of which can ordinarily bring down the other.

• Presidents are usually limited to a specified number of terms in office; usually two.

• Little overlap in membership between the executive and the legislature.

• President serves as head of government as well as head of state.

• Examples: Afghanistan, Argentina, Brazil, Egypt, Indonesia, Nigeria, United States.

FOCUS 9.1 The separation of powers

The separation of powers is the hallmark of the presidential system: executives have the power to lead and to execute, legislatures have the power to make law, and courts have the power to adjudicate. While there is certainly an overlap in practice, the focus of responsibilities is generally clear, and is typically reinforced by a separation of personnel. Neither the president nor members of the cabinet can sit in the legislature, creating further distance between the two institutions. Similarly, legislators must resign their seats if they wish to serve in the government, meaning the president’s ability to buy members’ votes with the promise of a job is self-limiting.

Contrasting methods of election create a natural difference of interests. Legislators depend only on the support of voters in their home district, while the president (and the president only) is elected by a broader constituency – typically, the entire country. This divergence generates the political dynamic whereby the president pursues a national agenda as distinct from the special and local interests of the legislature. So, despite the focus on a single office, presidential government divides power. The system creates a requirement for the executive to negotiate with the legislature, and vice versa, and thereby ensures the triumph of deliberation over dictatorship.

There is a practical separation of powers in parliamentary systems as well, in the sense that executive and legislative functions are distinct. But members of the executive also sit in the legislature, and rather than legislators having to resign in order to serve in government, occupying a seat in the legislature is all but a prerequisite to being appointed to a top government job, such as the head of a government department. Above all, the very survival of the executive in a parliamentary system depends on it retaining the legislature’s confidence.

Separation of powers: An arrangement in which executive and legislature are given distinct but complementary sets of powers, such that neither can govern alone and that both should, ideally, govern together.

Under these circumstances, there is a danger that presidents will grow too big for their boots. In the past, Latin American and African presidents have frequently amended the constitution so as to continue in office beyond their one- or two-term limits. Even worse, a frustrated or ambitious president can turn into a dic-tator; presidential democracies are more likely than parliamentary democracies to disintegrate (Cheibub, 2002).

Presidential government predominates in the Americas, and is also found in many African countries, such as Nigeria. The United States is the representative case, and as such provides important insights into how the presidential executive works. The framers of the US constitution wanted to create an office that could both make decisions and be prevented from accumulat-ing too much power. They also wanted to insulate the office from influence by the ‘excitable masses’, so they created an Electoral College within which each state had a specific number of votes, all of which – in most cases – go to the candidate who wins the most votes in each state. Controversially, it is possible for a presidential candidate to win the popular vote but lose in the College, as Al Gore discovered in his defeat by George W. Bush in 2000.

In addition to a general obligation to oversee the execution of laws, the president is given explicit duties (such as commander-in-chief) that have been interpreted over time as giving presidents further implied powers. For instance, presidents can claim executive privilege: the right to withhold information from Congress and the courts which, if released, would damage the president’s capacity to execute the laws. Presidents can also issue executive orders, statements, and proclamations. At the same time, they also often find their hands tied, because they share important powers with Congress:

• The president is commander-in-chief but only Congress can declare war.

• The president can make government appointments and sign treaties, but only with the consent of the Senate.

• The president can veto legislation, but Congress can override the veto.

• Congress, not the president, controls the purse strings.

Describing the relationship between the president and Congress as a separation of powers is misleading, because there is in reality a separation of institutions: the two share authority, each seeking to influence the other but neither being in a position to dictate. In parliamentary systems, prime ministers can normally rely on strong support in the legislature from their party or coalition; this is rarely the case in presidential executives.

The paradox of the American presidency – a weak governing position amid the trappings of omnipotence – is reflected in the president’s support network. To meet presidential needs for information and advice, a con-glomeration of supporting bodies has evolved, including the White House Office, the National Security Council, and the Office of Management and Budget. Collectively, they provide far more direct support than is available to the prime minister in a parliamentary system, forming what is sometimes known as the ‘institutional presidency’ (Burke, 2010).

Relative to parliamentary systems, the US presidential system lacks a strong cabinet. There is a federal cabinet, but it is not mentioned in the constitution, its meetings are usually little more than a presidential photo opportunity, and cabinet members often find it hard to gain access to the president through the thicket of advisers. As we will see later, presidential government is never cabinet government as it formally is in parliamentary executives.

Cabinet: A body consisting of the heads of the major government departments. Sometimes known as a Council of Ministers. More important in parliamentary than in presidential systems.

The norm in a presidential system is for the president to be elected separately from the legislature. Presidential survival (if not success) is thus independent of party numbers in the legislature, and the president is tied to a national constituency while members of the legislature are elected from local districts. This is not how matters are organized in South Africa, however, which offers an interesting variation on the theme of a presidential executive. It has a president, but the officeholder is elected by members of the legislature rather than in a direct national vote. This makes the South African president more like a prime minister in a parliamentary system, particularly since the president is usually head of the largest party in the legislature. However, the South African president is both head of state and head of government, is limited to two five-year terms in office, and while required to be a member of the legislature in order to qualify to be president, must resign from the legislature upon election as president. Only two other countries – Burma and Botswana – use this system. Determining the political impact of this rare format has been complicated by the dominance in post-apartheid South Africa of a single party, the African National Congress.Were legislative elections to produce no clear majority party, it would be interesting to see how the election of the president would be affected.

Parliamentary executives

Unlike presidential systems, in which the chief executive is separate from the legislature and independently elected,the executive in a parliamentary government is organically linked to the assembly. The leader (the prime minister, or – in Germany and Austria – the chancellor) is normally the head of the largest party in parliament (or head of one of the parties in the governing coalition), continues to hold a seat in parliament while also running the country, works in conjunction with a separate head of state who has little substantive power, and is subject neither to a separate election nor to term limits. Most government ministers are also members of parliament (although, in some countries – such as Sweden – this dual mandate is not allowed). Like presidents, prime ministers make appointments to other key government institutions, but these are rarely subject to confirmation by the legislature. And in two other key contrasts with the presidential executive, a prime minister can be removed from office as the result of a vote of no confidence, and can usually call new elections before the full term of a legislature has run its course.

TABLE 9.2: Parliamentary executives

• Prime minister (or chancellor, premier) is normally head of the biggest political party in the legislature.

• Governments emerge from the legislature and the prime minister can be dismissed from office by losing a legislative majority or a vote of confidence.

• Executives can serve an unlimited number of terms in office.

• The executive is collegial, taking the form of a cabinet (or council of ministers) in which the prime minister is traditionally first among equals. The cabinet typically contains around two dozen members.

• Prime minister is head of government, working with a separate ceremonial head of state.

• Examples: most European countries, Australia, Canada, India, Japan, New Zealand.

Parliamentary government: An arrangement in which the executive emerges from the legislature (most often in the form of a coalition), remains accountable to it, and must resign if it loses a legislative vote of no confidence.

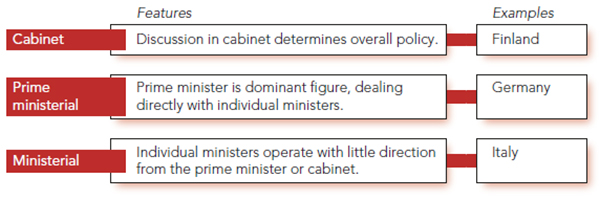

Parliamentary government lacks the clear focus of the presidential system on a single chief executive, and instead involves a subtle and variable relationship between prime minister, cabinet, and government ministers. Figure 9.1 distinguishes between cabinet, prime ministerial, and ministerial governments; examining the balance between these nodes in the governing network, and how they are changing over time, helps us better appreciate the realities of parliamentary government.

For advocates of the parliamentary system, cabinet government has the advantage of encouraging more deliberation and collective leadership than occurs in a presidential system. When Olsen (1980: 203) wrote that ‘a Norwegian prime minister is unlikely to achieve a position as superstar’, many advocates of parliamentary government would have regarded his comment as praise. Finland provides a clear case of cabinet government at work: by law, the Finnish State Council (the cabinet) is granted extensive decision-making authority, prime ministers are mainly chairs of Council meetings, and it is at these meetings that decisions are reached and compromises made. Meanwhile, both the prime minister and individual ministers are subject to constraints arising from Finland’s complex multi-party coalitions. But the system works best in smaller countries; in many larger countries, the number and complexity of decisions means they cannot all be settled around the cabinet table.

As regards prime ministerial government, the guiding principle is hierarchy rather than collegiality. Germany has an arrangement known as a ‘chancellor democracy’ in which the Bundestag (Germany’s lower house) appoints the chancellor, and accountability to the Bundestag is mainly through the chancellor’s office. The chancellor answers to parliament, while ministers answer to the chancellor. The strong position of Germany’s chief executive derives from the Basic Law (the German constitution) which says that the ‘chancellor shall determine, and be responsible for, the general policy guidelines’.

FIGURE 9.1: Types of parliamentary government

Note: None of these features is institutionalized or constitutionalized. Instead, each is a matter of politics and tradition.

Several commentators suggest that parliamentary executives are moving in the direction of prime ministerial government; prime ministers have ceased to be primus inter pares (first among equals) and have instead become president-ministers. Writing of Canada, Savoie (1999) suggests that in setting the government’s agenda and taking major decisions, there is no longer any inter or pares, only primus. Similarly, Fiers and Krouwel (2005: 128) argue that since the 1990s prime ministers in Belgium and the Netherlands have acquired more prominent and powerful positions, transforming these democracies into a kind of ‘presidentialized’ parliamentary system. King (1994) identified three factors at work: increasing media focus on the prime minister, the growing international role of the chief executive, and the emerging need for policy coordination as governance becomes more complex. A substantial prime minister’s office reflects these distinctive responsibilities and reinforces prime ministerial authority.

The third type is ministerial government, which arises when ministers operate without extensive direction from either prime minister or cabinet.This decentralized pattern can emerge either from respect for expertise, or from the realities of a coalition. Looking again at Germany, the chancellor sets the overall guidelines but the constitution goes on to say that ‘each Federal Minister shall conduct the affairs of his department autonomously and on his own responsibility’. Ministers are appointed for their knowledge of the field and are expected to use their professional experience to shape their ministry’s policy under the chancellor’s guidance. So, Germany mixes two models, operating ministerial government within the framework of chancellor democracy.

In many coalitions, parties appoint their own leading figures to head particular ministries, again giving rise to ministerial government. In the Netherlands, for instance, the prime minister does not appoint, dismiss, or reshuffle ministers. Cabinet members serve with, but certainly not under, the government’s formal leader. In these conditions, the prime minister’s status is diminished, with ministers owing more loyalty to their party than to either the prime minister or the cabinet. The chief executive is neither a chief nor an executive but, rather, a skilled conciliator. In India’s multi-party coalitions, too, open defiance of the prime minister is far from unknown (Mitra, 2014: 583).

In Japan, too, ministers must often operate without strong guidance from the prime minister. The prime minister is more like the keeper of the helm than captain of the ship and few officeholders leave a lasting personal stamp on government. Turnover has been rapid: while the United States had four presidents and Britain had four prime ministers between 1990 and 2015, Japan had 14 prime ministers serving 21 terms among them, some of those terms lasting only a matter of months. The comparison is with Italy (see Chapter 8) rather than the United States or Britain. In Japan, limits are placed on prime ministerial power by the powerful bureaucracy and upper legislative chamber, factions within political parties, other party leaders, and the consensus style of Japanese politics. In particular, prime ministers from the leading Liberal Democratic Party are limited by the requirement to secure regular re-election as party leader. Japanese prime ministers are far from powerless, because they can – for example – hire and fire members of the cabinet and all other senior members of the government. And reflecting the wider international trend towards a focus on the prime minister, Shinzō Abe (prime minister, 2006–7, 2012–) has achieved a higher domestic and international profile than most of his predecessors. Even so, the contrast with, say, Germany’s chancellor democracy remains acute.

If the paradox of the presidential executive is weakness amid the appearance of strength, the puzzle of parliamentary government is to explain why effective government can still emerge from the mutual vulnerability of legislature and executive. The solution is clear: the party provides the necessary unifying device, bridging government and legislature in a manner that presidential systems are designed to prevent. Where a single party has a parliamentary majority, government can be stable and decisive, perhaps excessively so. But majority governments are increasingly rare, with the result that the typical parliamentary executive is a coalition government or a minority administration. Looking in more depth at different kinds of coalitions provides more insight into how parliamentary executives work.

Majority, coalition, and minority governments

In presidential and semi-presidential systems of government, executives and legislatures are elected separately and have distinct powers. The reach and authority of presidents is impacted by party numbers in the legislature, but there is much that the president can do regardless. In parliamentary systems, by contrast, the executive and the legislature are fused, and the power of the executive depends greatly upon the party balance in the legislature. A prime minister whose party has a clear majority will be in a much stronger situation than one governing a coalition or running a minority government. For this reason, no review of parliamentary executives can be complete without taking each of these variations into account.

Majority government. Britain is the classic example of parliamentary government based on a single ruling party with a secure majority. The plurality (or winner-take-all) method of election (see Chapter 16) usually delivers a working majority in the House of Commons to a single party, the leader of that party normally becomes prime minister (PM), and the cabinet is made up of 20 or so parliamentary colleagues from the same party. The cabinet is still the formal lynchpin of the system: it is the focus of accountability to Parliament, formally ratifies important government decisions, and coordinates the work of government departments. Its political support is essential to even the strongest PM.

The key to the system’s stability is the party discipline that turns the cabinet into the master of the Commons, rather than its servant.The governing party spans the cabinet and the legislature, ensuring domination of the parliamentary agenda. The cabinet is officially the top committee of state but it is also an unofficial meeting of the party’s leaders. As long as senior party figures remain sensitive to the views of other Members of Parliament (MPs) (and, often, even if they do not), they can control the Commons. The government may emerge from the parliamentary womb but it dominates its parent from the moment of its birth.

How does the ruling party achieve this level of control? Each party has a Whip’s Office to ensure that MPs vote as its leaders require. Even without the attention of the whips, MPs will generally toe the party line if they want to become ministers themselves. In a strong party system such as Britain’s, a member who shows too much independence is unlikely to win promotion. In extreme cases, MPs are thrown out of their party for dissent and are then unlikely to be re-elected by constituents for whom a party label is still key. Whatever their personal views, it is in the interests of MPs to show public loyalty to their party.

Coalition and minority governments. It is quite usual in parliamentary systems (particularly those using proportional representation, discussed in Chapter 16) for no single party to win a majority after an election. In this situation, the tight link between the election result and government formation weakens, and government takes one of three main forms:

• A majority coalition government in which two or more parties with a majority of seats join together. This is the most common form of rule in continental Europe.

• A minority coalition or alliance in which parties, even working together, still lack a parliamentary majority. Minority coalitions have predominated in Denmark since the 1980s.

• A single-party minority government formed by the largest party. These are common in Norway and Sweden.

Coalition government: An arrangement in which the government is formed through an agreement involving two or more parties which divide government posts between them.

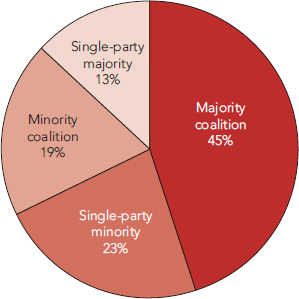

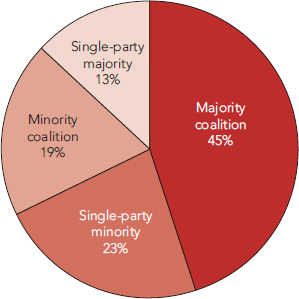

Figure 9.2 shows the party composition of West European governments in the second half of the twentieth century, revealing that majority coalitions were the most frequent, followed by single-party minority governments, minority coalitions, and single-party majority governments. So unusual are single-party majority governments that many national constitutions explicitly specify the hurdles a new government must clear before taking office. Some demand that the legislature shows majority support for a new government through a formal vote of investi-ture, a requirement that encourages the formation of a majority coalition with an agreed programme.

Others, however, do not require a majority vote for a new administration. In Sweden, for example, the proposed prime minister can form a government as long as no more than half the members of the Riksdag object (Bergman, 2000). This requirement is to avoid majority opposition rather than to achieve majority assent. Where constitutions say nothing on the procedure for approving a new government, as in Denmark, the new administration takes office – and continues in power – until and unless it is voted down by the legislature.These less demanding conventions facilitate the formation and survival of minority governments.

FIGURE 9.2: Governments in Western Europe, 1945–99

Note: Based on 424 governments from 17 countries. Non-party administrations (3 per cent) excluded.

Source: Adapted from Strøm and Nyblade (2007: table 32.1)

In regard to timing, some coalitions are promised or arranged before an election is held, helping voters to make a more informed judgement about the likely consequences of their voting choices. Most often, though, the coalitions are arranged after the election, with the outgoing government remaining as caretaker while negotiations are under way.Agreements can be reached in a matter of days, but the more complex negotiations take longer: it took 208 days for agreement on a new Dutch government in 1977, and a record 541 days (18 months) for a new Belgian government in 2010–11.

It would be logical to suggest that coalitions will form between the largest parties in the legislature, but this is rarely the case, and coalitions come in several different types. Most contain the smallest number of parties needed to make a viable government, which is typically, two to four. Party interests favour these ‘minimum winning coalitions’ (MWCs) because including additional parties in a coalition which already has a majority would simply dilute the number of posts and the amount of policy influence available to each participant.

In addition, coalitions are usually based on parties with adjacent positions on the ideological spectrum. These ‘connected coalitions’ particularly benefit centre parties, which can jump either way. In Germany, for instance, the small liberal Free Democrat Party has been a part of most coalitions, sometimes with the left-wing Social Democrats and, between 2009 and 2013, with the more conservative Christian Democrats. Either coalition could be presented as ideologically coherent. Germany, however, also has some experience of grand coalitions between the two major parties, marginalizing the Free Democrats. When the Free Democrats failed to win any seats at the 2013 election, Chancellor Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrats took the decision to form a grand coalition with the Social Democrats.

Occasionally, ‘oversized coalitions’ emerge, containing more parties than are needed for a majority. These arrangements typically emerge when the partners are uncertain about the stability of their pact, or there is need to address policy problems of a kind where it makes strategic sense to win the support of as many parties as possible. For example, when Hungary was in the throes of its post-communist reforms, the 1994 election gave the social democrats an absolute majority of 209 out of 386 seats. Even so, they invited the liberals (with 70 seats) to join them in an oversized coalition, and then launched an austerity programme that included unpopular cuts in public sector wages and employee numbers. Because the government had a broad-based coalition, its ability to impose unpopular policies in the interests of promoting the market economy was strengthened (Wittenberg, 1999).

Semi-presidential government: An arrangement in which an elected president coexists with a separately elected prime minister and legislature.

Semi-presidential executives

The third major form of executive is a combination of the presidential and the parliamentary, mix-ing both models to produce a distinct system with its own characteristics, advantages, and disadvantages. In semi-presidential government (otherwise known as a ‘dual executive’) we find both an elected president and a prime minister and cabinet accountable to the legislature. The president is separately elected, and shares power with a prime minister who heads a cabinet accountable to the legislature.The prime minister is usually appointed by the president, but must have the support of a majority in the legislature. The president is head of state, and shares the duties of being head of government with the prime minister; the president has an oversight role and responsibility for foreign affairs, and can usually take emergency powers, while the prime minister is responsible for day-to-day domestic government. The president has more opportunity to play the role of head of state than is the case with a presidential executive, but must also deal with a division of authority within the executive that creates the potential for a struggle between president and prime minister.

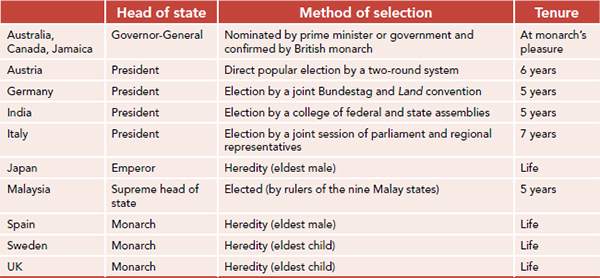

FOCUS 9.2 Heads of state in parliamentary systems

No analysis of parliamentary executives is complete without saying something about the distinction between the head of state and the head of government. The classic analysis was offered by the Victorian British commentator Walter Bagehot (a one-time editor of The Economist). In his book The English Constitution, he wrote of the two key elements of constitutions (boldface added):

first, those which excite and preserve the reverence of the population – the dignified parts, if I may so call them; and next the efficient parts – those by which it, in fact, works and rules ... every constitution must first gain authority and then use authority; it must first win the loyalty and confidence of mankind, and then employ that homage in the work of government. (Bagehot, 1867: 6)

Unlike presidential systems, which combine the offices of head of state and head of government, parliamentary systems separate the two positions. Dignified or ceremonial leadership lies with the head of state, while efficient leadership is based on the prime minister. Heads of state possess few significant political powers, and their job is primarily non-political, and to act as a unifying influence. Prime ministers, meanwhile, are the elected political leaders with executive power. This separation of roles creates more time for prime ministers to concentrate on running the country, and also helps to separate government and state in the public mind. Heads of state are not entirely non-political, however, and sometimes play a role in the formation of governments. In India, for example, the president had to oversee the formation of a caretaker government in 1979 that governed until new elections in 1980; stepped in on three occasions between 1996–7 to identify the party leader best placed to form a new government following indecisive elections; and was involved in 2004 in naming Manmohan Singh as prime minister after Congress Party leader Sonia Gandhi turned down the job.

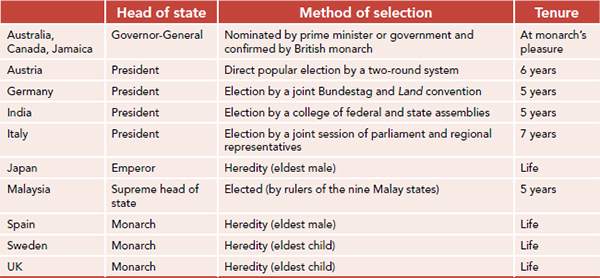

Heads of state are typically either monarchs who inherit their position, or presidents who are appointed or elected (see Table 9.3). Eight European countries – Belgium, Denmark, Luxembourg (a duchy), the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom – have a constitutional monarchy, while Malaysia’s supreme head of state provides a rare contemporary example of an elected monarch. Some former British colonies, such as Australia and Canada, have a governor-general who stands in for the monarch. Most monarchs are reluctant to enter the political arena in democratic times, but royal influence can occasionally be significant, especially in eras of crisis and transition. King Juan Carlos helped to steer Spain’s transition to democracy in the 1970s, for example, while the King of Belgium played a conciliatory role in his country’s long march to federal status between 1970 and 1993.

Elsewhere, heads of state in parliamentary systems are presidents, and are elected either through a popular vote (e.g. Ireland), by parliament (e.g. Israel), or by a special electoral college, often comprising the national legislature plus representatives from regional or local government (e.g. Germany).

TABLE 9.3: Selecting the head of state in parliamentary democracies

Constitutional monarchy: A state headed by a monarch, but where the monarch’s political powers are severely limited by constitutional rules. Stands in contrast with an absolute monarch (see Chapter 4).

The French political scientist Maurice Duverger (1980: 166) provided an influential definition of a semi-presidential system:

A political regime is considered semi-presidential if the constitution which established it combines three elements: (1) the president of the republic is elected by universal suffrage; (2) he possesses quite considerable powers; (3) he has opposite him, however, a prime minister and ministers who possess executive and governmental power and can stay in office only if the parliament does not show its opposition to them.

The ‘quite considerable powers’ of the president typically include special responsibility for foreign affairs, appointing the prime minister and cabinet, issuing decrees and initiating referendums, initiating and veto-ing legislation, and dissolving the assembly. In theory, the president can offer leadership on foreign affairs, while the prime minister addresses the needs of domestic politics through parliament.

In cases where the president’s party has a majority in the legislature, the power advantage lies with the presi-dent; the prime minister and the cabinet both follow the president’s lead, and the prime minister promotes the president’s programme in the legislature. But when voters give an opposition party a majority in the legislature, the president has no choice but to work with a prime minister and cabinet from that party in an arrangement known as ‘cohabitation’. In such circumstances, the prime minister must cooperate with the president in the national interest, but also becomes the leader of the opposition in what is, in effect, a grand coalition. An ambitious prime minister can also use the position to build the foundations for later contesting the presidency.

TABLE 9.4: Semi-presidential executives

• Combines an elected president and an appointed prime minister.

• President usually appoints the prime minister and can dissolve the legislature.

• President usually serves a limited number of fixed-length terms.

• Prime minister and cabinet are accountable to both the president and the legislature.

• President serves as head of state and shares the responsibilities of being head of government with the prime minister.

• Examples: France, Mongolia, Russia, Sri Lanka, Ukraine, several former French colonies in Africa.

Shugart and Carey (1992) distinguish between two kinds of semi-presidential government: president- parliamentary and premier-presidential. In the former (found in Peru and Russia), the prime minister and the cabinet are collectively responsible to both the president and the legislature, meaning that they can be dismissed by one or the other. In the latter (found in France, Portugal, Romania, and Ukraine since 2005), the prime minister and cabinet are collectively responsible only to the legislature, meaning that while the president can appoint the prime minister and the cabinet, they can only be removed from office through a vote of no confidence in the legislature. As a result, the position of the president is weakened.

If the United States exemplifies the presidential system, France provides the archetype of the semi- presidential executive. In an effort to move away from the unstable Fourth Republic, which had seen 23 prime ministers in its short 12-year life, the 1958 constitution of the Fifth Republic created a presidency fit for the dominating presence of its first occupant, Charles de Gaulle (president, 1959–69). De Gaulle saw himself as a national saviour, arguing that ‘power emanates directly from the people, which implies that the head of state, elected by the nation, is the source and holder of that power’ (Knapp and Wright, 2006: 53). The president has been directly elected since 1962, with recent modifications introducing slight limitations. In 2000, the presidential term was reduced from seven to five years, with a two-term limit following in 2008.

The French president is guarantor of national independence and the constitution, heads the armed forces, negotiates treaties, calls referendums, presides over the Council of Ministers, dissolves the National Assembly (but cannot veto legislation), appoints (but cannot dismiss) the prime minister, and appoints other ministers on the recommendation of the prime minister and dismisses them.

The main concern of French prime ministers is with domestic affairs, casually dismissed by de Gaulle as including such mundane matters as ‘the price of milk’. Appointed by the president but accountable to parliament, the prime minister formally appoints ministers and coordinates their day-to-day work, operating within the president’s style and tone.The ability of the assembly to force the prime minister and the Council of Ministers to resign after a vote of censure provides the parliamentary component of the semi-presidential executive.

TABLE 9.5: Comparing executives

Presidents and prime ministers need to work in harmony, a task made easier when the same party controls both branches of government. This is usually the case, but occasionally France has gone through a period of cohabitation. Between 1986 and 1988, for example, the socialist president François Mitterrand had to share power with the conservative prime minister Jacques Chirac. The latter won the presidency in 1995, and was obliged in turn to share power with socialist prime minister Lionel Jospin between 1997 and 2002. This arrangement intensifies competition between the two principals, and places the president in the awkward position of leading both the country and the opposition.

Beneath the president and prime minister, the government’s day-to-day political work is carried out by 20 senior ministers, but the Council of Ministers is less significant than the cabinet in parliamentary systems. Most modern French governments have been multi-party coalitions, the Council of Ministers involves more ritual than discussion, ministers are more autonomous because they often come to their job with a background in their given policy area, and interventions by the prime minister and the president are often to resolve disputes, rather than to impose an overall agenda.

Executives in authoritarian states

So far we have looked at executives in democratic settings, and at the many nuances bearing on what are complex institutions. Constitutional rules and political realities help define what a democratic executive can or cannot do, and they both shape and protect the structures of government. By contrast, understanding executives in authoritarian states is more about political realities; there are constitutions and rules, to be sure, but there is less constraint on their capacity to execute policy, and there are fewer formal protections on the officeholder. As Svolik (2012: 39) points out, dictators lack the support of independent political authorities that would help them enforce agreements, as well as the rules that govern the work of formal government institutions. As a result, the violent resolution of conflicts is an ever-present possibility. In short, authoritarian leaders can wield more power and yet they also often face greater personal risks than their democratic counterparts.

The characteristic form of the executive in hybrid and authoritarian regimes is presidential, but as we saw in Chapter 4 the term president takes on a quite different meaning from what we find in democracies. Presidential government in authoritarian settings provides a natural platform for leaders who seek to set themselves apart from – and above – all others. In such systems, the president operates without the same constitutional restraints faced by the chief executive of a liberal democracy. Instead, presidents use what they define as their direct mandate from the people to cast a shadow over competing institutions such as the courts and the legislature. Excepting the simplest systems, though, they do not usually go so far as to reduce these bodies to completely token status.

Authoritarian leaders seek to concentrate power on themselves and their supporters, not to distribute it among institutions; it is this lack of institutionalization that is the central feature of the authoritarian executive. Although developed in the context of African politics, the idea of personal rule developed by Jackson and Rosberg (1982) travels widely through the authoritarian world. Politics takes precedence over government, and personalities matter more than institutions: there is, in other words, a feast of presidents but a famine of presidencies.

Personal rule: A form of rule in which authority is based less on office as such than on personal and often corrupt links between rulers and patrons, associates, clients and supporters. Personal rule can be stable but remains vulnerable because of its dependence upon persons rather than institutions.

The result of personal rule is often a struggle over succession, insufficient emphasis on policy, and poor governance. In particular, the lack of a succession procedure (excepting hereditary monarchies) can create a conflict among potential successors not only after the leader’s exit, but also in the run-up to it. Authoritarian leaders keep their job for as long as they can ward off their rivals. They must monitor threats and be prepared to neuter those who are becoming too strong. Politics comes before policy.

The price of defeat, furthermore, is high; politics in authoritarian systems can be a matter of life and death. When the leaders of Western democracies leave office, they can often give well-paid lectures, write and sell their memoirs for large sums, be appointed to well-paid consultancies, or set up foundations to do good works. Ousted dictators risk a harsher fate, assuming they even live long enough to have a ‘retirement’. Some might live in wealthy exile, a few languish in prison, and the least fortunate are murdered. It is hardly surprising, then, that the governing style of authoritarian rulers inclines to the ruthless.

Particularly in its most authoritarian phase before the 1990s, post-colonial Africa illustrated the importance of personal leadership in non-democratic settings. Leaders were adept at using the coercive and financial resources of the regime to reward their friends and punish their enemies. As an example, Sandbrook (1985) wrote this of the administration of Mobutu Sese Seko during his dictatorial tenure as president of Zaire (1965–97):

No potential challenger is permitted to gain a power base. Mobutu’s officials know that their jobs depend solely on the president’s discretion. Frequently, Mobutu fires cabinet ministers, often without explanation. Everyone is kept off balance. Everyone must vie for his patronage.

However, in post-colonial Africa, as in other authoritarian settings, personal rule has been far from absolute. Inadequately accountable in a constitutional sense, many personal rulers have found themselves constrained by other political actors, including the military, leaders of ethnic groups, landowners, the business class, the bureaucracy, multinational companies, and even factions in the leader’s own court.

To survive, leaders have to distribute the perks of office so as to maintain a viable coalition of support. Enemies can be bought off by allowing them a share of the pie, but their slice must not become so large as to threaten the big man himself. Mobutu’s own ground rules illustrate the dilemma: ‘if you want to steal, steal a little in a nice way. But if you steal too much to become rich overnight, you’ll be caught’ (Gould, 1980: 485).

In the Middle East, personal rule remains central to those authoritarian regimes that survived the Arab Spring of 2011. The absolute monarchs discussed in Chapter 4 continue to rule oil-rich kingdoms in traditional patriarchal style. ‘Ruling’ rather than ‘governing’ is the appropriate term. In Saudi Arabia, for instance, advancement within the ruling family depends less on merit than on proximity to the family’s network of advisers, friends, and guards. Public and private are interwoven, each forming part of the ruler’s sphere. Government posts are occupied on the basis of good behaviour, as demonstrated by unswerving loyalty to the ruler’s personal interests.

Such systems of personal rule have survived for centuries, limiting the development of strong institutions. The Arab Spring revealed their weaknesses, as frustrated populations in several Arab states protested against the absence of opportunity in corrupt, conservative regimes headed by ageing autocrats. But the challenges of switching from autocracy to democracy were also revealed. In the case of Egypt, Hosni Mubarak was ousted from office in 2011 in the wake of demonstrations against his 30-year regime, and in 2012 the country’s first ever truly competitive elections resulted in the victory of Mohamed Morsi. But because he came from the Islamist Muslim Brotherhood, nervous-ness grew abroad, particularly in the United States. And when Morsi started showing signs of authoritarianism, he was removed in a July 2013 military coup. Military leader Abdel Fattah el-Sisi then reinvented himself as a civilian, won elections held in May 2014, and quickly showed an unwillingness to tolerate opposition. After a brief and hopeful flirtation with democracy, Egypt was soon back to its old ways. This was not what most Egyptians wanted, and opposition to the el-Sisi regime began to grow; the point, though, is that Egypt’s other political institutions were too weak to resist a return to personal rule.

The theme of the president operating without the constitutional restraints found in democracies is illustrated by Vladimir Putin’s Russia. Formally, Russia is a semi-presidential system arranged along French lines, with a directly elected president coexisting with a chairman of the government (i.e. prime minister) who is nominated by the president and approved by the Duma (the lower chamber of the legislature).

In some minor respects, the Russian president’s position is only slightly stronger than that of a US president. Both are limited to two terms in office, but the Russian leader can stand again after a term out. Both are subject to impeachment but the threshold is more demanding in Russia: the US requires only a majority of members in favour in the House of Representatives, while Russia requires a two-thirds majority in both parliamentary chambers plus confirmation by the courts.

In reality, though, Russian presidents can grasp the levers of power more easily than either their American or French equivalents. Under the 1993 constitution, the president acts as head of state, commander-in-chief, and guarantor of the constitution. In the latter capacity, presidents can suspend the decisions of other state bodies. They can also issue decrees, though these can be overridden by legislation. In contrast to most semi-presidential systems, the president can remove ministers without the consent of the Duma, and does so.

Russia’s president is also charged with ‘defining the basic directions of the domestic and foreign policy of the state’, and with ‘ensuring the coordinated functioning and collaboration of bodies of state power’. These broad duties affirm Russia’s long tradition of executive power, a norm which both predates and was reinforced by the communist era. Strong government is regarded as a necessary source of effective leadership for a large and sometimes lawless country.

Putin had no choice but to step down as president upon the completion of his two terms in 2008, but he continued to hold on to power through the cynical means of becoming prime minister to the weak new president, Dmitry Medvedev. As president, Medvedev’s influence seemed to be marginal compared with his predecessor, and he was little more than a place-holder awaiting Putin’s return in 2012. And with the term of a president increased from four years to six, Putin could reasonably look forward to running Russia (his health allowing) until 2024. So, even in Russia, with its powerful state institutions centred on the Kremlin, a substantial measure of personal rule is superimposed on the institutions of state.

China is the most important example of the supremacy of politics over government in an authoritarian setting. It combines some formal features of a semi-presidential system with political dominance by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). In understanding this system, two points are key. First, in spite of China’s intricate governmental structure (which includes a cabinet, a legislature, and a network of supporting agencies), these bodies do little more than legitimize the decisions already taken by the party leadership (Saich, 2015: ch. 4).Second, identifying who holds power is less a question of formal titles and offices than of understanding links across institutions, personal networks, and the standing of key figures in the system. For instance, Deng Xiaoping was ‘paramount leader’ of China from 1978 until his death in 1997, yet the most senior posts he ever held were those of party vice chairman and chairman of the party’s Military Commission; by 1993, the only position of any kind that he held was the presidency of China’s bridge association. So even in China, with its enormous population, we see strong elements of personal rule.

As China’s politics has stabilized, so recent changes have given a government that looks more like some of its democratic counterparts. At the apex is the president, who is nominated by the leadership of the Chinese legislature, the National People’s Congress (NPC), and then elected (or confirmed) by the NPC for a maximum of two five-year terms.The presidency is mainly a ceremonial head of state, but has many conventional executive powers, such as the ability to appoint (with NPC approval) all members of the State Council (the functional equivalent of a cabinet). The officeholder is also conventionally head of the CCP and of the Central Military Commission, posts that provide enormous political power. The president must also work with a premier, who is the de facto head of government, is always a senior member of the party, and is nominated by the president and confirmed by the NPC. The CCP continues to drive the governmental machine.

Military leaders are perhaps the ultimate form of the authoritarian executive, combining as they do control over civilian and military institutions. But while great power in democracies is said to come with great responsibilities, in military dictatorships it also comes with great risks. Executives in democratic states must always worry about their standing in the opinion polls, their capacity to work with legislatures, and threats to their leadership from others seeking power; for their part, military leaders face threats that are both closer to home (from within the ruling elite) and more unpredictable and violent. When Winston Churchill said that ‘dictators ride to and fro on tigers from which they dare not dismount’, he was speaking in the context of the rise of Hitler and Mussolini, but the adage also applies to military leaders who must be constantly on the look-out for threats from numerous quarters.

The story of Nigeria’s leaders is illustrative. Since independence in 1960, it has had 15 leaders: six civilian presidents (although two of these six were former military leaders who came back to office as civilians) and nine military leaders. Of the 15, three were removed from office through military coups in which the leaders were killed, and four were removed from office but survived. All have had to keep a careful eye on critics within the military, who have always been ready to organize opposition and, if necessary, a coup to remove the incumbent.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

• What are the advantages and disadvantages of dividing the roles of head of state and head of government?

• Separation of powers: a good idea or not?

• Is presidential or parliamentary government the most appropriate system for (a) new democracies, (b) divided societies?

• Have prime ministers become presidential and, if so, why?

• ‘Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown’ (Shakespeare, Henry IV Part II). Discuss in the context of democracies and of authoritarian states.

KEY CONCEPTS

Cabinet

Coalition government

Constitutional monarchy

Head of government

Head of state

Parliamentary government

Personal rule

Presidential government

Semi-presidential government

Separation of powers

FURTHER READING

Elgie, Robert (2011) Semi-Presidentialism: Sub-Types and Democratic Performance. Examines how different forms of semi-presidentialism affect the quality and durability of democracy.

Han, Lori Cox (ed.) (2011) New Directions in the American Presidency. Explores current themes in the study of the presidential system in the United States.

Helms, Ludger (2005) Presidents, Prime Ministers and Chancellors: Executive Leadership in Western Democracies. A comparison of the political executive in Britain, Germany, and the United States.

Lijphart, Arend (ed.) (1992) Parliamentary versus Presidential Government. A classic collection of essays on parliamentary and presidential government.

Poguntke,Thomas and Paul Webb (eds) (2005) The Presidentialization of Politics: A Comparative Study of Modern Democracies. An investigation of whether the operation of the executive has become more presidential in a range of liberal democracies.

Strøm, Kaare, Wolfgang C. Müller, and Torbjörn Bergman (eds) (2008) Cabinets and Coalition Bar-gaining:The Democratic Life Cycle in Western Europe. A comparative examination of cabinet formation.

Federal presidential republic consisting of 26 states and a Federal District. State formed 1822, and most recent constitution adopted 1988.

Federal presidential republic consisting of 26 states and a Federal District. State formed 1822, and most recent constitution adopted 1988. Bicameral National Congress: lower Chamber of Deputies (513 members) elected for renewable four-year terms, and upper Senate (81 members) elected from the states (three members each) for renewable eight-year terms.

Bicameral National Congress: lower Chamber of Deputies (513 members) elected for renewable four-year terms, and upper Senate (81 members) elected from the states (three members each) for renewable eight-year terms. Presidential. A president directly elected for no more than two consecutive four-year terms.

Presidential. A president directly elected for no more than two consecutive four-year terms. A dual system of state and federal courts, with justices of superior courts nominated for life by the president and confirmed by the Senate. Supreme Federal Court serves as constitutional court: 11 members, nominated by president and confirmed by Senate for life, but must retire at 70.

A dual system of state and federal courts, with justices of superior courts nominated for life by the president and confirmed by the Senate. Supreme Federal Court serves as constitutional court: 11 members, nominated by president and confirmed by Senate for life, but must retire at 70. A two-round majority system is used for elections to the presidency and the Senate, while elections to the Chamber of Deputies use proportional representation.

A two-round majority system is used for elections to the presidency and the Senate, while elections to the Chamber of Deputies use proportional representation. Multi-party, with more than a dozen parties organized within Congress into four main coalitions and a cluster of non-attached parties.

Multi-party, with more than a dozen parties organized within Congress into four main coalitions and a cluster of non-attached parties.