PREVIEW

The comparison of political systems focuses mostly on activities at the national level, but it can just as easily focus on more localized activities, and involve comparison of regional, city, and local governments.The functional equivalents of national executives, legislatures, and courts can all be found at the regional level, at least in federal systems, and no understanding of politics and government in a given state can be complete without looking at the full picture. Unfortunately, sub-national politics tends to attract less interest among voters, who – for example – tend to turn out at regional and local elections in much smaller numbers than at national elections. This is ironic, given that many of the services that most immediately impact their lives come from sub-national government, and local officials are usually more accessible than their national counterparts.

This chapter begins with a review of the concept of multilevel governance, which describes the many horizontal and vertical interactions that often exist among different tiers of government. It then looks at the two most common models for the functioning of systems of national government: unitary and federal. Unitary systems are found in most countries, but many people live under federal governments because most of the world’s largest countries are federations. The chapter then compares and contrasts unitary and federal systems before looking at the structures and functions of local government. It ends with a review of the dynamics of sub-national government in authoritarian regimes, where – more often than not – the periphery is marginal to the centre.

CONTENTS

• Sub-national government: an overview

• Multilevel governance

• Unitary systems

• Federal systems

• Comparing unitary and federal systems

• Local government

• Sub-national government in authoritarian states

KEY ARGUMENTS

| • Multilevel governance is a framework for examining the relationships among different levels of administration (supranational, national, regional, and local). |

| • Most countries in the world use a unitary form of government, in which regional and local units are subsidiary to national government. |

| • Other countries are federal, made up of two or more levels of government with independent powers. But there is no uniform template for a federal system, and federations come in many different forms. |

| • Although the constitutional contrasts between unitary and federal systems are clear, unitary states are just as tiered as federal states – and often more so. The strengthening of regional government is a signifi cant trend within unitary states. |

| • Local government is still the place where the citizen most often meets the state. Regrettably understudied, its organization and functioning raise some interesting questions, including the enabling authority of elected mayors. |

| • Sub-national government in authoritarian states has less formal power and independence than its democratic equivalent, but authoritarian rulers often depend on local leaders to sustain their grip on power. |

Sub-national government: an overview

Sub-national government and politics describe the institutions and processes found below the level of the state. While national or central government (the terms are interchangeable) concerns itself with the interests of the entire state, and with the relationships that exist among sovereign states, sub-national government focuses almost entirely on domestic matters. It involves different kinds of mid-level government (states, provinces, or regions within a country), as well as local government units of the kinds found in towns, cities, and other localities, and coming under a variety of names, including counties, communes, prefectures, districts, boroughs, and municipalities.

Every country orders sub-national government in one of two ways: as a unitary system or as a federal system. In the former, national government has sole sovereignty, meaning that mid-level and local government exists at the pleasure of national government, with only as much power as is granted to it by the centre. In the latter, the national and regional governments possess independent existence and powers; neither level can abolish the other. There are many nuances in the manner in which unitary and federal systems are arranged; both types come in different varieties, a picture that is further complicated by federal systems that function more like unitary systems (such as Russia), and unitary systems that function more like federal systems (such as Britain and Spain).

Unitary system: One in which sovereignty rests with the national government, and regional or local units have no independent powers.

Federal system: One in which sovereignty is shared between two or more levels of government, each with independent powers and responsibilities.

About two dozen countries are constitutionally established as federations, but because they include almost all the largest countries (the most obvious exception being China), they contain a substantial share of the world’s population: about 37 per cent to be exact. Nearly 90 per cent of the member states of the United Nations are unitary, but because many of them are so small, they are home to only 63 per cent of the world’s population (or only 43 per cent if we exclude China).

The internal relationships within unitary states differ from those in federal states, as does the way in which citizens view government. In unitary systems, politics tends to be focused at the national level. Lower tiers still matter, but the most substantial political issues are national in scope, and there is more of a sense among citizens that they are part of the state political community. In federal systems, by contrast, the various local units have more independence, their agendas can achieve more prominence, and they matter more in the political calculations of citizens. Furthermore, because they have independent powers, states within federations have more leverage relative to national government than is the case in unitary systems.

Some of the states within federal systems are substantial political and economic units in their own rights. California, for example, has a bigger economy than India, Canada, Mexico, or Saudi Arabia. Meanwhile, the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, with a population just short of 200 million, is the same size as Brazil and bigger than Japan or Russia. In short, sub-national government is an important part of comparative studies, it merits close consideration.

Multilevel governance

Multilevel governance (MLG) is a term used to describe how policy-makers and interest groups in liberal democracies, whether unitary or federal, find themselves discussing, persuading, and negotiating across multiple tiers in their efforts to deliver coherent policy in specific functional areas such as transport and education. The underlying argument is that no one level of government acting alone can resolve most policy problems, and thus that multiple levels must cooperate. MLG is defined by Schmitter (2004: 49) as follows:

an arrangement for making binding decisions that engages a multiplicity of politically independent but otherwise interdependent actors – private and public – at different levels of territorial aggregation in more-or-less continuous negotiation/deliberation/implementation, and that does not assign exclusive policy competence or assert a stable hierarchy of political authority to any of these levels.

Multilevel governance: An administrative system in which power is distributed and shared horizontally and vertically among different levels of government, from the supranational to the local, with considerable interaction among the parts.

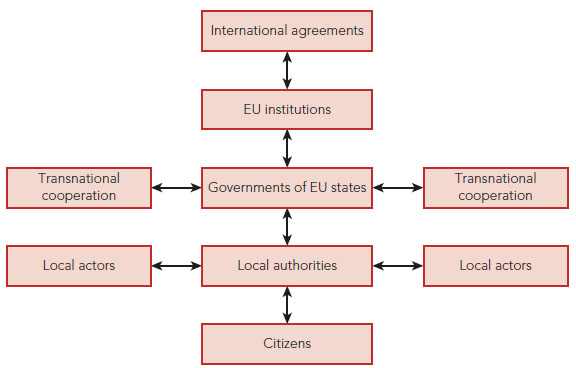

Communication is not confined to officials working at the same or adjacent levels. Rather, international, national, regional, and local officials in a given sector will form their own policy networks, with interaction through all tiers (see Figure 11.1 for an illustration of MLG in the European Union). The use of the term ‘governance’ instead of ‘government’ directs our attention to these relationships between institutions, rather than simply the organizations themselves.

The idea of multilevel governance carries a further implication. As with pluralism, it recognizes that actors from a range of sectors – public, private, and voluntary – help to regulate society. In the field of education, for example, the central department will want to improve educational attainment in schools; but, to achieve its target, it will need to work not only with lower tiers within the public sector (such as education boards), but also with wider interests such as parents’ associations, teachers’ unions, private sector suppliers, and educational researchers.

In common with pluralism, MLG can be portrayed in a positive or negative light. On the plus side, it implies a pragmatic concern with finding solutions to shared problems through give-and-take among affected interests. On the negative side, it points to a complicated, slow-moving form of regulation by insider groups, resisting both democratic control and penetration by less mainstream groups and thinking. Multilevel governance may be a fashionable term but its popularity should not lead us to assume that the form of rule it describes is optimal.

Understanding MLG requires an appreciation of the resources all tiers bring to the table. Typically, the national level has political visibility, large budgets and strategic objectives, but officials from lower levels will possess their own power cards: detailed knowledge of the problem and the ability to judge the efficacy of the remedies proposed. If lower tiers are both resourced and enthused, they can make a difference; if not, they may lose interest, limiting the ability of the centre to achieve its policy goals.

It would be wrong to infer that power in multilevel governance is merely the ability to persuade. Communication still operates in a constitutional framework that provides both limits and opportunities for representatives from each tier. If the constitution allocates responsibility for education to central government, local authorities are unlikely to build new schools unless the department of education signs the cheque. Thus, the formal allocation of responsibilities remains the rock on which multilevel governance is built; it develops from, without replacing, multilevel government.

FIGURE 11.1: Multilevel governance in the European Union

Most states in the world have a unitary form of government, meaning that while they have regional and local political institutions, sovereignty lies exclusively with the national government. Sub-national administrations, whether regional or local, can make and implement policy, but they do so by leave of the centre. And while sub-national government can adopt local laws and regulations, it can only do so on topics that are not the preserve of national government. Reflecting this central supremacy, the national legislature in most unitary states has only one chamber, since there is no need for a second house to represent entrenched provinces.

Unitary systems have emerged naturally in societies with a history of rule by sovereign monarchs and emperors, such as Britain, France, and Japan. In such circumstances, authority radiates from a historic core. Unitary structures are also the norm in smaller democracies, particularly those without strong ethnic divisions. In Latin America, nearly all the smaller countries (but neither of the two giants, Argentina and Brazil) are unitary. The countries of Eastern Europe have also chosen a unitary structure for their post-communist constitutions, viewing federalism as a spurious device through which Russia tried to obscure its dominance of the Soviet Union.

In contrast to the complexities of federalism (discussed later in this chapter), a unitary structure may seem straightforward and efficient: there is one central government that holds all the cards that matter, other levels doing only what they are allowed to do by the centre. However, the location of sovereignty is rarely an adequate guide to political realities, because unitary government is often decentralized. Indeed, there has been an effort in recent decades in many unitary states to push responsibility for more functions to lower levels.

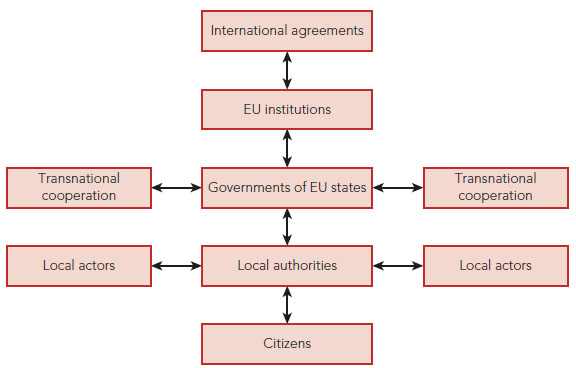

There are three ways in which this can happen (see Figure 11.2). The first is deconcentration, through which central government tasks are relocated from the capital to other parts of the country. Deconcentration spreads the work around, can help bring jobs and new income to poorer parts of the country, reduces costs by allowing activities to move to cheaper areas, and frees central departments to focus on policy-making rather than execution. So, for example, routine tasks such as issuing passports can be deconcentrated to an area with higher unemployment and lower costs. Deconcentration is made easier by the internet, because so much government work can be done online that geographical location has become less important.

FIGURE 11.2: Dispersing power in unitary systems

Note: Deconcentration and decentralization occur in federal as well as unitary states.

The second and politically more significant way of dispersing power is through delegation. This involves transferring or delegating powers from central government to sub-national bodies, such as local authorities, and has been very much in favour in recent decades. Treisman (2007: 1) notes that, along with democracy, competitive markets, and the rule of law, this form of decentralized government ‘has come to be seen as a cure for a remarkable range of political and social ills’. Sceptics raise doubts, however, noting that many policy problems – such as economic management – are better dealt with in a unified fashion at the national level.

Scandinavia is the classic example of delegation, where local governments put into effect many welfare programmes agreed at national level. Sweden in particular has seen an exceptional array of implementation tasks delegated by the national parliament (the Riksdag) to regional and local authorities. County councils focus in particular on health care and aspects of transport and tourism, while lower-level municipalities administer a wide range of responsibilities, including education, city planning, rescue services, water and sewage, waste collection and disposal, and civil defence. Together with transparency, accountability and autonomy for civil servants, such extensive delegation forms part of what has been described as the ‘Swedish model’ (Levin, 2009).

The third and most radical form of power dispersal is devolution. This occurs when the centre grants decision-making autonomy (including some legislative powers) to lower levels. Spain is an example here.Where once it was tightly controlled from the centre, its regions were strengthened in the transition to democracy following the death of Francisco Franco in 1975, and devolution has continued apace ever since. The Basque region in the north of the country possesses substantial self-government, and Catalonia in the east was recognized as a distinct nationality in 2006. Although Spain is often treated as a de facto federation, in theory its framework is unitary but devolved.

In the UK, too, the contrast with federations remains even after devolution. Britain is formally a unitary state, because although devolved assemblies were introduced in Northern Ireland in 1998 and in Scotland and Wales in 1999, they could theoretically be abolished by the national government in London through normal legislation. Because of problems stemming from the institution of the Northern Irish peace agreement, for example, the Northern Ireland Assembly was suspended between 2002 and 2007, and elections were postponed. This could not normally happen in a federal system. But the position of Scotland within the UK remains difficult and continues to pose a threat to the survival of the entire kingdom, whether federal or unitary. Although a referendum in Scotland on independence for the country was narrowly defeated in 2014, the pro- independence Scottish National Party swept the board in Scotland at the 2015 British general election, winning 56 of the 59 parliamentary seats there. The future of the ‘United’ Kingdom remains firmly on the agenda.

Regional government

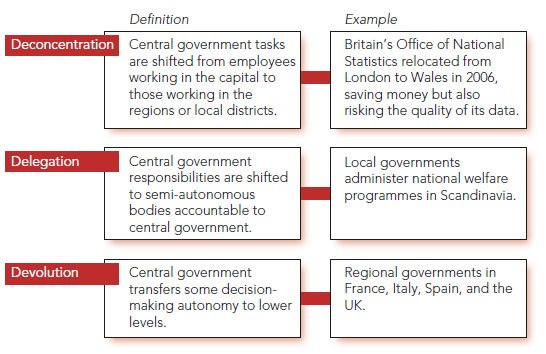

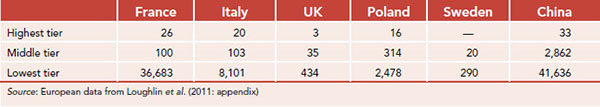

The creation and expansion of the middle tier of government – the regional level – has been an important trend in many unitary states. In a study of 42 mainly high-income countries between 1950 and 2006, Hooghe et al. (2010: 54) found that 29 saw an increase in regional authority compared with only two showing a decline. The larger the country, the more powerful this middle tier tended to be. As a result of these developments, unitary states such as France, Italy, and Poland now have three levels of sub-national government: regional, provincial, and local (Table 11.1). By contrast, China has gone further, with five levels ranging from provinces to villages. The result is an intricate multilevel system of government.

TABLE 11.1: Sub-national government in unitary states

Regional government: Middle-level government in unitary states that takes place below the national level and above the local and county levels.

In origin, many regions were merely spatial units created by the centre to present figures on inequalities within a country and to spark policies to reduce them. But in most large unitary states, specific regional organizations were soon established, and became an administrative vehicle through which the centre could decentralize planning. Regional bodies took responsibility for economic development and related public infrastructure; notably, transport. These bodies were not always directly elected, and were typically created by a push from the centre, rather than a pull from the regions. Regions now provide a valuable middle-level perspective below that of the country as a whole but above that of local areas. Amalgamation of local governments can achieve some of the same effect but often at greater political cost, given the importance of traditional communities to many inhabitants.

A key factor influencing the development of regional institutions is whether or not they are directly elected. Election enhances visibility but, for better or worse, political and partisan factors come to intrude more directly into their operations. France is an example of this transition. The 22 regional councils established there in 1972 at first possessed extremely limited executive powers. However, their status was enhanced by a decentralization law passed in 1982 providing for direct election. The first round of these elections took place in 1986. Even though French regional bodies continue to operate with small budgets, they have won greater visibility and authority.

The case for direct election is perhaps strongest where regions are already important cultural entities, providing a focus for citizens’ identities. In the United Kingdom, for example, the national government succeeded in establishing regional assemblies in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, where national loyalties were well established, but failed to generate much enthusiasm for its efforts to create elected regional assemblies in England.

The European Union has encouraged the development of a regional level within its member states. The European Regional Development Fund, established in 1975, distributes aid directly to regions, rather than through central governments. The EU went further in 1988 by introducing a Committee of the Regions composed of sub-national authorities. But this proved to be merely consultative, and national executives remain more central to the policy process than the more committed proponents of regional governance in the EU had envisaged.

Federal systems

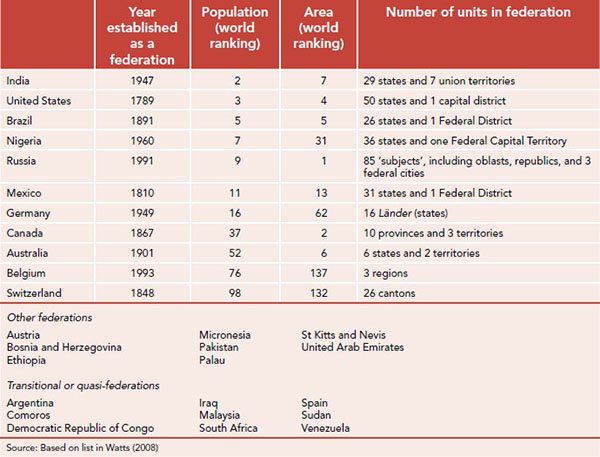

In contrast to unitary systems of government, where power rests at the national level, sovereignty and power in federal systems are shared among different levels of government within a single state. By definition there must be at least two such levels, but there are typically three: national, regional, and local. (The terminology can be confusing: the national or central government is usually known as the federal government, and the regional governments are known variously as states, provinces, or in Germany and Austria as Länder – see Table 11.2.) Federalism usually works best either in large or deeply divided countries, and about two dozen countries meet the definition of a federation, including Brazil, India, Russia, and the United States. Despite its size and diversity, China remains unitary because this allows for tighter control by the Communist Party.

Federation: A political system that puts federalism into practice.

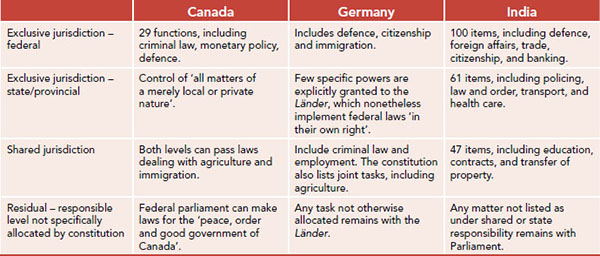

The key point about a federal partnership is that neither the national nor the regional tier can abolish the other, and it is this protected position of the regional governments – not the extent of their powers – that distinguishes federations from unitary states. Federations allocate specific functions to each tier, so that the centre usually takes charge of external relations (defence, foreign affairs, and immigration) as well as key domestic functions, such as the national currency. The states, meanwhile, are usually left in charge of education, law enforcement, and local government, and residual powers often lie with the states, not the centre (see Table 11.3). In nearly all federations, the states have a guaranteed voice in national policy-making through an upper chamber of the national legislature, in which each state normally receives equal or nearly equal representation.

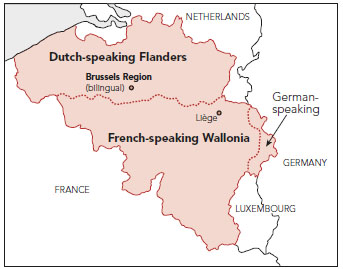

There are two routes to a federation: the first – and most common – involves creating a new central authority for previously separate political units (‘coming together’), and the second involves transferring sovereignty from an existing national government to lower levels (‘holding together’). Australia, Canada, Nigeria, Switzerland, and the United States are examples of the first kind, while Belgium is the main example of the second. First established in 1830, Belgium has been beset by divisions between its French- and Dutch-speaking regions.After constitutional revisions in 1970 and 1980, which devolved more power to these separate groups, the country finally became a federation in 1993, with three regions:

TABLE 11.2: The world’s federations

• Predominantly French-speaking Wallonia in the south, including a small German-speaking community.

• Dutch-speaking Flanders in the north.

• The Brussels region, centred on the bilingual but mainly French-speaking capital (see Map 11.1).

MAP 11.1: The regions of Belgium

TABLE 11.3: Comparing Canadian, German and Indian federations

Variations on the theme of federalism

Just as there is no fixed template for a unitary system of government, so federations differ in terms of their internal dynamics.The baseline would be a symmetrical arrangement in which all the states within a union were similar in size, wealth, and influence, but this never happens. The reality is an asymmetric federalism which arises when some states are more powerful than others (because they are bigger or wealthier) or are given more autonomy than others, typically in response to cultural differences. In India, for example, Uttar Pradesh in India is 182 times bigger in terms of population than the state of Mizoram, while the Brazilian state of São Paulo is 88 times bigger than the state of Roraima. As an example of cultural asymmetry, Quebec nationalists in Canada have long argued for special recognition for their French-speaking province, viewing Canada as a compact between two ‘equal’ communities (English- and French-speaking, the former outnumbering the latter by 4:1) rather than as a contract between ten equal provinces.

Asymmetric federalism: The phenomenon of states within a federation having unequal levels of power and influence due to size, wealth, and other factors.

It was usual in most federations during the twentieth century for national governments to steadily gain power, helped by three main factors:

• The flow of money was more favourable to the centre as tax revenues grew with the expansion of economies and workforces. For independent revenue, states must depend on smaller and less dynamic sales and property taxes.

• National government benefited from the emergence of national economies demanding overall coordination.

• Wars and depressions empowered some national governments, while the post-1945 expansion of the welfare state enhanced European governments still further.

Since the 1980s, however, the trends have become less clear-cut. On the one hand, big projects run by the centre have gone out of fashion, partly because national governments have found themselves financially stretched in eras of lower taxation and financial crisis. On the other hand, the centre has still sought to provide overall direction.

Dual federalism: National and local levels of government function independently from one another, with separate responsibilities.

Cooperative federalism: The layers are intermingled and it is difficult always to see who has ultimate responsibility.

Where dual federalism provided the original inspiration for the US, Europe (and especially Germany and Austria) has found more appeal in the contrasting notion of cooperative federalism. Where the US federation was based on a contract in which the states joined together to form a national government with limited functions, the European form rests on the idea of cooperation between levels, with a shared commitment to a united nation binding the participants together.The moral norm is solidarity and the operating principle is subsidiarity: the idea that decisions should be taken at the lowest feasible level.The national government offers overall leadership but implementation is the duty of lower levels: a division, rather than a separation, of tasks.

The motives behind the creation of federations tend to be more often negative than positive; fear of the consequences of remaining separate must overcome the natural desire to preserve independence. Rubin and Feeley (2008: 188) suggest that federalism becomes a solution when, in an emerging state, ‘the strong are not strong enough to vanquish the weak and the weak are not strong enough to go their separate ways’.

Historically, the main incentive for coming together has been to exploit the economic and military bonus of size, especially in response to strong competitors. Riker (1996) emphasized the military factor, arguing that federations emerge in response to an external threat. The 13 original American states, for instance, joined together partly because they felt vulnerable in a predatory world. However, US and Australian federalists also believed that a common market would promote economic development.

A more recent motivation has been ethnic federalism, as with the Belgian case. Further south, Switzerland integrates 26 cantons, four languages (German, French, Italian, and Romansh), and two religions (Catholic and Protestant) into a stable federal framework. But the danger with federalizing a divided society is that it can reinforce the divisions it was designed to accommodate. The risk is particularly acute when only two communities are involved, because the gains of one group are the losses of another. Federations are more effective when they cut across (rather than entrench) ethnic divisions, and when they marginalize (rather than reinforce) social divisions.

The challenges faced by Nigeria are illustrative. It became independent in 1960 with three regions, added a fourth in 1963, replaced them with 12 states in 1967, and has since cut the national cake into ever smaller pieces in an effort to prevent the development of powerful states based around particular ethnic groups. There are now 36 states and a Federal Capital Territory, and yet regionalism and ethnic divisions continue to handicap efforts to build a sense of Nigerian unity.

Subsidiarity: The principle that no task should be performed by a larger and more complex organization if it can be executed as well by a smaller, simpler body.

Since its inception in 1949, the Federal Republic of Germany has been based on interdependence, not independence. All the Länder (states) are expected to contribute to the success of the whole, and in return are entitled to respect from the centre. The federal government makes policy but the Länder implement it, a division of administrative labour expressed in the constitutional requirement that ‘the Länder shall execute federal laws as matters of their own concern’. But this cooperative ethos has come under increasing pressure from a growing perception that decision-making has become cumbersome and opaque. Constitutional reforms finalized in 2006 sought to establish clearer lines of responsibility between Berlin and the Länder, giving the states – for example – more autonomy in education and environmental protection. Although this package represents a move away from cooperative federalism towards greater subsidiarity, consultation remains embedded in German political practice.

The waters of federalism have been muddied by developments in several countries that have never legally declared themselves to be federations, but where the transfer of powers to regional units of government has resulted in a process of federalization. In Britain, for example, the creation in the 1990s of regional assemblies in Scotland,Wales, and Northern Ireland made all three more like states within a federal United Kingdom; all that is missing is an equivalent English regional assembly. In Argentina, Spain, and South Africa, too, powers have devolved to provinces and local communities without the formal creation of a federation, creating de facto federations or quasi-federations.

Quasi-federation: A system of administration that is formally unitary but has some of the features of a federation.

South Africa is an interesting case of a quasi-federation.When the Union of South Africa was created in 1910, it brought together four British colonies that had different and distinctive histories, and that might have followed the Australian and Canadian lead and formed a federation. Today the country has nine provinces, several of which have close historical and cultural links with important minorities: Afrikaners (white Africans with Dutch heritage) are associated with the Free State, Zulus (who still have their own king) with Kwazulu-Natal, and white South Africans with British heritage with the Eastern Cape and the Western Cape. The provinces have their own premiers and cabinets, and have powers over health, education, public housing, and transport, making them similar in many ways to states within a federation.

The final variation on the theme of federalism is a looser form of political cooperation known as a confederation. Where a federation is a unified state, within which power is divided between national and sub-national levels of government, and where there is a direct link between government and citizens (the national government exercises authority over citizens, and is answerable directly to the citizens), a confederation is a group of sovereign states with a central authority deriving its authority from those states, and citizens linked to the central authority through the states in which they live. The central authority remains the junior partner and acts merely as an agent of the component states, which retain their own sovereignty.

Confederation: A looser form of a federation, consisting of a union of states with more powers left in the hands of the constituent members.

While the number of federations worldwide has grown, there have been few examples in history of confederations, and none have lasted; they include the United States from 1781 to 1789, Switzerland from 1815 to 1848, and Germany from 1815 to 1866. The only political association that might today be described as a confederation is the European Union (see Lister, 1996). It is not a federal United States of Europe, but neither has it formally declared itself to be a confederation, leaving it literally nameless as a political form. Many commentators avoid giving it a label at all, simply describing it as sui generis, or unique. The extent to which it has or has not federalized is best illustrated through comparison; Table 11.4 contrasts the EU with the United States, showing some areas of similarity but others of marked contrast.

TABLE 11.4: Comparing the United States and the European Union

| United States | European Union | |

| Founding document | A constitution | Treaties |

| Single federal government | Yes | No |

| Elected legislature | Yes | Yes |

| Single market (free movement of people, money, goods, services) | Yes | Incomplete |

| Single currency | Yes | In 18 of 28 states |

| Single legal citizenship | Yes | No |

| Federal tax | Yes | No |

| Common trade policy | Yes | Yes |

| Common foreign and defence policies | Yes | Much collaboration, but no common policies as such |

| Combined armed forces | Yes | No |

| Single seat at meetings of international organizations | Yes | Some, but not in United Nations, for example |

| Shared identity | Yes | Yes, but most Europeans identify primarily with their home state |

Comparing unitary and federal systems

As is almost always the case in comparative exercises, a review of unitary and federal systems reveals that both have their strengths and weaknesses, their advantages and disadvantages, and their particular idiosyncrasies. The case for unitary government is that it normally provides enough government and regulation for smaller societies, encourages a sense of national unity where citizens feel that they are all involved in the key public issues of the day, and makes sure that there are common standards and regulations. The case for federalism is that it offers a natural and practical arrangement for organizing large or divided states, providing checks and balances on a territorial basis, keeping some government functions closer to the people, and allowing for the representation of cultural, economic, and ethnic differences.

Federalism also reduces overload in the national executive, while the existence of multiple states or provinces produces healthy competition and opportunities for experiment. States can also move ahead even when the federal level languishes; hence while the federal government in the United States has been slow to respond to demands for action on same-sex marriage, climate change, gun control, and the legalization of marijuana, individual states have often gone ahead with their own responses. Citizens and businesses also have the luxury of choice inside a federal system: if they dislike governance in one state, or feel that it offers them only limited personal or employment opportunities, they can easily move to another.

But a case can also be mounted against federalism. Compared with unitary government, decision-making in a federation is complicated, slow-moving, and hesi-tant. When a gunman ran amok in the Australian state of Tasmania in 1996, killing 35 people, federal Australia experienced some political problems before it succeeded in tightening gun control uniformly across the country. An even worse outrage in 2012 in Newtown, Connecticut, which resulted in the deaths of 20 children and six staff, generated almost no significant change in policies outside the state of Connecticut. By contrast, unitary Britain acted speedily in banning guns when a comparable incident occurred in 1996 at a primary school in Dunblane, Scotland, resulting in the deaths of 16 children and one teacher.

Federalism can also place the political interests of rival governments above the resolution of shared problems. Fiscal discipline becomes harder to enforce, which is why several Latin American federations have struggled to control their free-spending (and free-riding) provinces. Extravagant spending by provinces – aware that they will be bailed out, if necessary, by the centre – can dent the fiscal strength of the federal state as a whole (Braun et al., 2003).

TABLE 11.5: The strengths and weaknesses of federalism

| Strength | Weakness |

| A practical arrangement for large or divided countries. | May be less effective in responding to security threats. |

| Provides stronger checks and balances. | Decision-making is slower and more complicated. |

| Allows for the recognition of diversity. | Can entrench internal divisions. |

| Reduces overload at the centre. | The centre finds it more difficult to launch national initiatives. |

| Encourages competition between states or provinces and allows citizens to move between them. | How citizens are treated depends on where they live. |

| Offers opportunities for policy experiments. | Complicates accountability: who is responsible? |

| Allows small units to cooperate in achieving the economic and military advantages of size. | May permit majorities within a province to exploit a minority. |

| Brings government closer to the people. | Basing representation in the upper chamber on states violates the principle of one person, one vote. |

Any final judgement on federalism must consider the proper balance between the concentration and diffusion of political power. Should it rest with one body in order to allow decisive action, as it does in unitary systems? From this perspective, federalism is likely to be seen as an obstacle and impediment, and even as an anti-democratic device. Alternatively, should power be dispersed so as to reduce the danger of majority dictatorship? Through this lens, federalism appears as an indispensable aid to liberty.

Local government

Local government is universal, found in unitary and federal states alike. It may be the lowest level of elected territorial organization, but it is ‘where the day-to-day activity of politics and government gets done’ (Teune, 1995: 16). The terrorist attacks in the United States in 2001, in Spain in 2004, in Britain in 2005, and in India in 2008, were events of national and global significance, but it was local officials in New York, Madrid, London, and Mumbai who faced the immediate task of providing emergency services. Given its role in service delivery, local government should not be what it tends to be: the forgotten tier. And we should not forget the quip of the American politician Tip O’Neill that ‘all politics is local’, implying as it does that the success of politicians is closely tied to their ability to meet the demands of local voters.

At its best, local government expresses the virtues of limited scale. It can represent natural communities, remain accessible to its citizens, reinforce local identities, offer a practical education in politics, provide a recruiting ground to higher posts, serve as a first port of call for citizens, and distribute the kinds of resources that matter most immediately to people.Yet, local governments also have weaknesses: they are often too small to deliver services efficiently, lack sufficient fundraising powers to set their own priorities, and are easily dominated by traditional elites.

The balance struck between intimacy and efficiency varies over time. In the second half of the twentieth century, local governments were encouraged to become more efficient, leading to larger units. For example, the number of Swedish municipalities fell from 2,500 in 1951 to 274 in 1974 (Rose, 2005: 168), and today stands at 290. In Britain, where efficiency concerns have been a high priority, the average population served by local authorities had reached more than 142,000 by 2007, the highest in Europe (Loughlin et al., 2011: appendix 1).

Towards the end of the twentieth century, signs emerged of a rebirth of interest in citizen involvement, stimulated by the need to respond to declining turnout at local elections. In New Zealand, successful managerial reforms introduced in 1989 were followed by the Local Government Act (2002), which outlined a more expansive, participatory vision for local authorities.

Similarly, where Dutch local government had once been preoccupied with a concern for effectiveness and efficiency, the emphasis during the 1990s switched to public responsiveness (Denters and Klok, 2005: 65). In 1995, Norway resolved that ‘no further amalgamations should be imposed against the wishes of a majority of residents in the municipalities concerned’ (Rose, 2005: 168). This cycling between efficiency and participation concerns suggests not only a real trade-off between the two, but also the difficulty of arriving at a stable balance between them.

Functions and structure

The broad tasks of local governments are twofold. First, they provide an extensive and often significant range of local public services, including public libraries, local planning, primary education, provision for the elderly, refuse collection, and water supply. Second, they implement national welfare policies.

This static description of functions fails to reveal how the role of local government has evolved since the 1980s, particularly in those countries where large local governments perform significant functions. One important trend, especially prominent in the English-speaking world and Scandinavia (see Chapter 10), has been for municipal authorities to reduce their direct provision of services by outsourcing to non-governmental organizations, both profit-making and voluntary. In theory, most local government services – from libraries to street-cleaning – can be outsourced, with potential gains in efficiency and service quality. But in practice these benefits are not always achieved, creating some risk in the transfer, and leaving us with the broader question of whether direct provision of services by a local government to the citizen is intrinsically preferable to delivery by a contractor to a consumer.

Global city: A city that holds a key place within the global economic system via its financial, trade, communications, or manufacturing status. Examples include Dubai, London, Moscow, New York, Paris, Shanghai, and Tokyo.

With most of the world’s people now living in urban areas, the question of how cities are best governed has become more pressing, as has the question of how best to treat the interdependence of cities and suburbs. The argument that they should be treated as single metropolitan areas – as city regions – has proved difficult to address given traditional boundaries. To complicate matters, cities confront distinctive issues arising from their social diversity. Within a concentrated area, they embrace rich and poor, natives and immigrants, black and white, gay and straight, believers and atheists, in a kaleidoscopic combination.

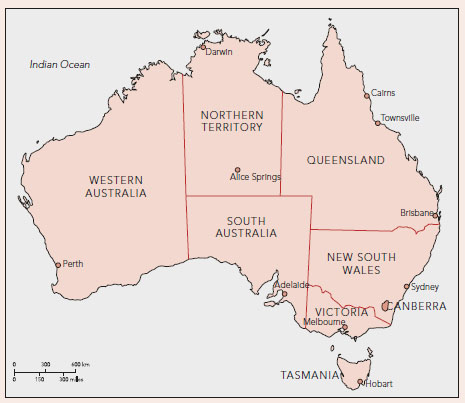

Not all countries have made a success of metropolitan governance, as the case of Australia shows (Gleeson and Steele, 2012). It is a nation of cities, with the five largest state capitals – Adelaide, Brisbane, Melbourne, Perth, and Sydney – being home to nearly two-thirds of the country’s people (see Map 11.2). These urban areas are inadequately governed in the existing three-tier (national, state, local) federation. National involvement in running cities is limited by the constitution; state administrations must also confront other pressures (including those from rural areas); and local government itself is subordinate and fragmented, with 34 local authorities operating in Sydney alone. A federal structure does not mesh well with a population concentrated in a few large cities.

In the governance of cities, the national capital occupies a special place. As an important component of the national brand, the capital’s leaders merit regular communication with the central government. But the capital’s international connections (and even those of major non-capital cities such as Frankfurt, New York, Hong Kong, Mumbai, and São Paulo) mean it can become semi-detached from its national moorings, as implied by the notion of a global city. Even though they are located in the same country, the interests of the centre and the capital can diverge. Inevitably, the capital is treated differently from other cities, providing further complexity to the idea of multilevel governance.

MAP 11.2: The cities of Australia

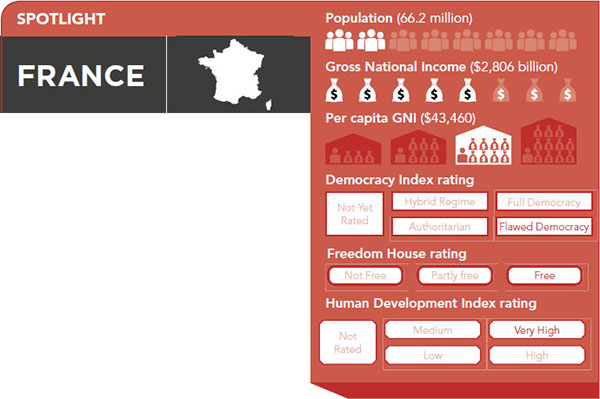

Brief Profile: France is an important European state facing the challenge of adapting its unique traditions to a more competitive world. The country has a reputation for exceptionalism based on the long-term impact of the French Revolution of 1789, which created a distinctive ethos within France. As with other states built on revolution – such as the United States – France can be considered an ideal as well as a country. However, where American ideals led to pluralism, the French state is still expected to take the lead in implementing the revolution’s ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity. As the country became more modern, urban, and industrial after 1945, however, so French uniqueness declined: retreat from empire left France, as Britain, as a middle-ranking power with a new base in the European Union, its society made more complex by immigration from North Africa, and its economy and governing elites challenged by globalization.

Form of government  Unitary semi-presidential republic. State formed 1789, and most recent constitution (the Fifth Republic) adopted 1958.

Unitary semi-presidential republic. State formed 1789, and most recent constitution (the Fifth Republic) adopted 1958.

Legislature  Bicameral Parliament: lower National Assembly (577 members) elected for renewable five-year terms, and upper Senate (348 members) indirectly elected through local governments for six-year terms.

Bicameral Parliament: lower National Assembly (577 members) elected for renewable five-year terms, and upper Senate (348 members) indirectly elected through local governments for six-year terms.

Executive  Semi-presidential. A president directly elected for no more than two five-year terms, governing with a prime minister who leads a Council of Ministers accountable to the National Assembly. There is no vice president.

Semi-presidential. A president directly elected for no more than two five-year terms, governing with a prime minister who leads a Council of Ministers accountable to the National Assembly. There is no vice president.

Judiciary  French law is based on the Napoleonic Codes (1804–11). The Constitutional Council has grown in significance and has had the power of judicial review since 2008. It has 12 members serving single nine-year terms. Three are former presidents of France, and three each are appointed by the incumbent president, the National Assembly, and the Senate.

French law is based on the Napoleonic Codes (1804–11). The Constitutional Council has grown in significance and has had the power of judicial review since 2008. It has 12 members serving single nine-year terms. Three are former presidents of France, and three each are appointed by the incumbent president, the National Assembly, and the Senate.

Electoral system  A two-round system is used for both presidential and legislative elections, with a majority vote needed for victory on the first round.

A two-round system is used for both presidential and legislative elections, with a majority vote needed for victory on the first round.

Parties  Multi-party, with the Socialists dominating on the left, backed by greens, leftists and radicals, while the Union for a Popular Movement dominates on the right. The far-right National Front has been making gains, moving France more towards a three-party system.

Multi-party, with the Socialists dominating on the left, backed by greens, leftists and radicals, while the Union for a Popular Movement dominates on the right. The far-right National Front has been making gains, moving France more towards a three-party system.

Outsourcing represents an evolution from providing to enabling. The enabling authority does not so much provide services as ensure that they are supplied. In theory, the authority becomes a smaller, coordinating body, more concerned with governance than government. In addition to outsourcing, a greater number of organizations can become involved in local policy-making, many of them functional (e.g. school boards), rather than territorial (e.g. county governments). This more coordinating and strategic approach is often linked to a growing concern among local governments with economic development, especially in attracting inward investment.

Unitary government in France

France has three levels of local government: regions (22), départements (96), and municipalities (nearly 37,000). Adding to the complexity of the picture, it also has six overseas regions or counties (including French Guiana and French Polynesia), and ‘intercommunalities’, which bring together départements and municipalities.

The network of départements was created by Napoleon early in the nineteenth century, and each is run by its own prefect and elected assembly. Napoleon called prefects ‘emperors with small feet’ but, in practice, the prefect must cooperate with local and regional councils, rather than simply oversee them. The prefect has ceased to be the local emperor and is instead an agent of the département, representing interests upwards as much as transmitting commands downwards. Many other countries have adopted this model, including all France’s ex-colonies and several post-communist states.

In 1972, the départements were grouped into 22 regions, each with their own elected councils, as well as regional economic and social committees that have an advisory role. Meanwhile, the basic unit of government is the commune, governed by a council and a mayor. Communes vary in size from a few dozen people to several tens of thousands, although most have populations of less than 1,500; a recent trend has been for the smallest commune to amalgamate with their neighbours. More pressures have been exerted on local government in recent years by the efforts of the French government to cut spending in order to control the national budget deficit. In spite of this, every commune has a mayor and a council based in the local city hall, and each has the same powers regardless of size.

In France, national politicians often become or remain mayor of their home town. This simultaneous occupancy of posts at different tiers is known in France as the cumul des mandats (accumulation of offices). Even after the rules were tightened in 1985 and 2000, the most popular cumul – combining the office of local mayor with membership of the National Assembly – is still allowed. It is an entrenched tradition reflecting the fused character of French public authority even in an era of decentralization.

There are two broad ways of organizing local government (see Table 11.6). The first and most traditional method is the council system. This arrangement concentrates authority in a college of elected councillors which is formally responsible for overseeing the organization’s work. The council often operates through powerful committees covering the main local services. The mayor is appointed by the council itself, or by central government, and has relatively few powers. Whatever virtues this format may have, its col-legiate character presents an opaque picture to residents and the wider world.

One example of the council system is the historic network of panchayat (literally, ‘assemblies of five’) found in India and the neighbouring countries of Bangladesh, Nepal, and Pakistan. Traditionally consisting of groups of respected elders chosen by the village to settle disputes, India’s panchayat have grown in significance (and acquired a more structured character) as more administrative functions have been moved to the local level, and as the bigger gram panchayats have been elected, each with a sarpanch (elected leader).There are now three levels of panchayat: those based in individual villages (of which there are nearly 600,000 in India), those bringing together clusters of villages, and those covering districts within India’s 29 states. Although their financial resources remain limited, panchayats are protected by the constitution and remain embedded in India’s cultural attachment to the ideal of village self-governance.

TABLE 11.6: The structures of local government

| Description | Examples | |

| Council system | Elected councillors form a council which operates through a smaller subgroup or functional committees. The unelected mayor is appointed by the council, or by central government. | Belgium, Netherlands, Sweden, England, Ireland, South Africa, Australia, Egypt, India. |

| Mayor-council system | An elected mayor serves as chief executive. Councillors elected from local wards form a council with legislative and financial authority. | Brazil, Japan, Poland, and about half the cities in the United States, including Chicago and New York. |

The second method of organization is the mayor-council system. More presidential than parliamentary, it is based on a separation of powers between an elected mayor and an elected council. The mayor is chief executive; the council possesses legislative and budget-approving powers. Used in Brazil, Japan, and many large American cities (such as New York and Chicago), this highly political format allows a range of urban interests to be represented within an elaborate framework.The mayor is usually elected at large (from the entire area), while councillors represent specific neighbourhoods.

The powers given to the mayor and council vary considerably. In the ‘strong mayor’ version (such as New York City), the mayor is the focus of authority and accountability, with the power to appoint and dismiss department heads without council approval. In the ‘weak mayor’ format (such as London), the council retains both legislative and executive authority, keeping the mayor on a closer leash. Whether strong or weak, an elected mayor does at least offer a public face for the area.

In an era of falling voter turnout (which tends to be worst at local elections because of their second-order qualities; see Chapter 16), new efforts have been made in recent years to make local decision-making more visible to voters. One means for doing this – tried, for example, in Britain, Italy, and the Netherlands – has been to repackage mayors as public figureheads of the districts they represent, and to introduce direct mayoral elections. A high profile mayor, such as Boris Johnson in London, can enhance the district’s visibility not only within the area but also, and equally importantly, among potential visitors and investors.

Sub-national government in authoritarian states

Studying the relationship between centre and periphery in authoritarian states confirms the relative insignif-icance of institutions in non-democracies. Sub-national government is weak, authority flows down from the top, and bottom-up institutions of representation are subordinate. When national power is exercised by the military or a ruling party, these bodies typically establish a parallel presence in the regions, where their authority overrides that of formal state officials. For a humble mayor in such a situation, the main skill required is to lie low and avoid offending the real power-holders. Little of the pluralistic policy-making suggested by the notion of multilevel governance takes place and the more general description ‘central–local relations’ is preferable.

But it would be wrong to dismiss local government altogether. In truth, central rulers – just like medieval monarchs – often depend on established provincial leaders to sustain their own, sometimes tenuous, grip on power. Central–local relations therefore tend to be more personal and less structured than in a liberal democracy. Particularly in smaller countries, the hold on power of regional leaders is not embedded in local insti-tutions; instead, such rulers command their fiefdoms in a personal fashion, replicating the authoritarian pattern found at national level. Central and local rulers are integrated by patronage: the national ruler effectively buys the support of local bigwigs who, in turn, maintain their position by selectively distributing state resources to their own supporters. Patronage, not institutions, is the rope that binds.

The weakness of modern institutions of sub-national government in many authoritarian regimes is reflected in, and perhaps even balanced by, the continued significance of traditional rulers. Nigeria offers an example. There, as in many of its colonies, Britain had strengthened the position of local rulers by governing indirectly through them, and these traditional elites remain influential. Nowhere is this clearer than in the Sokoto, a Nigerian state created in 1976 but with origins in an Islamic Sokoto caliphate of the early nineteenth century. Sokoto state is led by a governor, typically a military officer, but the position of sultan, who once ruled the caliphate, continues to exist. Indeed, the sultan remains the spiritual leader of Nigeria’s Muslims. In this way, traditional Islamic leadership coexists alongside conventional sub-national government.

Traditional political units in Nigeria retain the advantages over modern, post-colonial units of longevity, legitimacy, and deep roots in local culture (Graf, 1988: 186). By contrast, elected legislatures and competing political parties are alien and experience difficulty in establishing firm foundations. Nigerian federal governments face a dilemma: should the special place of traditional leaders in the community be exploited to extend the reach of federal government and to support programmes of modernization and democratization (which might then weaken the authority of traditional leaders), or should traditional leaders be bypassed and their powers reduced, thereby risking the anger of local Islamic communities and reducing the credibility of the federal government?

In some of the least stable states, the institutions of sub-national government are supplanted by opportunistic and/or informal control in the form of warlords. While much has been made of warlords’ recent role in Afghanistan and Somalia, they are far from a new phenomenon, and in some ways are perhaps the oldest form of political domination. Basing their control on military power, they are found sprinkled through the history of China, Japan, and Mongolia, and have been a more recent phenomenon in several parts of Africa and Asia.

Warlords: Informal leaders who use military force and patronage to control territory within weak states with unstable central governments.

Field research on warlords is, by definition, danger-ous, but our understanding of their motives and methods has improved thanks to their new prominence in several parts of the world. In a study of their role in Liberia, Sierra Leone, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Reno (1997) made the link between warlords and weak states with rich resources such as diamonds, cobalt and timber. For Marten (2012), warlords are not state-builders, like some of their feudal Asian and European predecessors, but instead rely on private militias to extract resources, enforce support and threaten state officials. They thrive on their capacity to provide brutal political control in situations where the formal institutions of state have failed to develop or simply failed.

In larger authoritarian states, such as China and Russia, sub-national government is more developed. Personal links remain important but institutional arrangements cannot be dismissed. Rather, sub-national government is actively exploited to ensure the continued power of the centre. China, for example, is a massive unitary state whose regions, with exceptions such as Hong Kong and Tibet, are ruled in imperial fashion from Beijing. Sub-national government takes the form of 22 provinces, 6 of which (Guangdong, Shandong, Henan, Sichuan, Jiangsu, and Hebei) each contain more than 70 million people, making them bigger than most countries. There are further subdivisions into either counties and townships, or cities and districts.

The Communist Party itself provides a method of integrating centre and periphery. In particular, the circulation of party leaders between national and provincial posts helps to connect the two tiers, providing China’s equivalent to the European cumul des mandats. Several provincial leaders serve on the party’s central politburo, and most members of this key body have worked in top provincial posts at some point in their career. It is these party linkages that provide the key channel through which Beijing maintains a measure of control over the country.

However, recent research suggests that the balance between the centre and the parts has changed. Zhong (2015) shows that after more than a decade of administrative and economic reform, central government has become increasingly remote and less important for many localities, and that the centre’s mobilization capacity has weakened. Increasingly, central government policies are ignored and local officials are often more interested in local or even personal projects than in centrally directed economic plans. This effective decentralization allows provinces to become laboratories for new policies but simultaneously accentuates inequalities between them, leading to occasional expressions of concern about the possibility of the country disintegrating.

By contrast to unitary China, Russia is a federation, but one in which the parts have less independence from the centre than is found in most federations. Although Russia saw a remarkable decentralization of power under Boris Yeltsin (president, 1991–9),Vladimir Putin has since overseen a recentralization of power, providing a contrast to the decline of central control in China. Putin’s success is based on four main developments:

• Establishing a uniform system designed to eliminate special deals established by Yeltsin with many regions.

• Acquiring the power of appointment and dismissal over regional governors.

• Creating seven extra-constitutional federal okrugs (districts) to oversee lower-level units. Each okrug is responsible for between 6 and 15 regions.These over-lords ensure that branches of the federal government in the regions remain loyal to Moscow.

• Reducing the powers of the Federation Council, the upper chamber of the national legislature, but giving the president the authority to appoint its members.

Through these devices, Putin has increased the capacity of the central state to govern the Russian people, so much so that Ross (2010: 170) concludes that ‘Russia is now a unitary state masquerading as a federation.’ Certainly, Putin’s reforms contributed to his project of creating what he termed a ‘sovereign democracy’ in Russia. In Putin’s eyes, a sovereign democracy is not built on the uncertain pluralistic foundations of multilevel governance. Rather, it gives priority to the interests of Russia, which include an effective central state capable of controlling its population. On that foundation, the Russian state seeks to strengthen its position in what it still sees as a hostile international environment.

• In what circumstances is a unitary system a more appropriate form of government, and in what circumstances is a federal system more appropriate?

• Why is there is no exact template for a unitary or a federal system, and does it matter?

• Should local governments replicate national governments and be headed by elected legislatures and executive mayors?

• How many global cities does your country have? If it has none, does this matter to national or local politics?

• Why is local government studied so much less than national government?

• Are sub-national government and politics more important in authoritarian states than in democracies?

KEY CONCEPTS

Asymmetric federalism

Confederation

Cooperative federalism

Dual federalism

Federal system

Federation

Global city

Multilevel governance

Regional government

Subsidiarity

Quasi-federation

Unitary system

Warlord

FURTHER READING

Bache, Ian and Matthew Flinders (eds) (2004) Multilevel Governance. Examines multilevel governance and applies the notion to specific policy sectors.

Burgess, Michael (2006) Comparative Federalism: Theory and Practice. A survey of the meaning of federalism, and approaches to comparing how it works in different societies.

Lazin, Fred, Matt Evans,Vincent Hoffmann-Martinot, and Hellmust Wollmann (eds) (2008) Local Government Reforms in Countries in Transition: A Global Perspective. A study of developments in local government in transitional states such as China, Colombia, Egypt, Poland, Russia, and South Africa.

Loughlin, John, Frank Hendriks, and Anders Lidström (eds) (2011) The Oxford Handbook of Local and Regional Democracy in Europe. Surveys sub-national democracy in 29 countries and assesses the Anglo, French, German, and Scandinavian state traditions.

Pierre, Jon (2011) The Politics of Urban Governance. Assesses four models of governance against the challenges facing cities.

Watts, Ronald J. (2008) Comparing Federal Systems, 3rd edn. Considers the design and operation of a wide range of federations.