It is perhaps unusual to argue that the cultural function of the figure of the child is defined by cruelty. That is, unless we are talking about the horror genre, in which case it is irresponsible not to point out that the child is the embodiment—if not the paradigmatic example—of the callous indifference to, or pleasure in causing, pain and suffering. In the Cold War comic book (1945–1960) in particular, the performance of criminality and juvenile delinquency is based upon the assumption that children are naturally inclined to acts of cruelty. Beginning with publications like Crime SuspenStories (EC, 1950–1955), Vault of Horror (EC, 1950–1955), and Tales from the Crypt (EC, 1950–1955), the shocking representation of horror emerges from the idea that the child is a villain through and through. 1 Yet this argument raises as many questions as it answers: What is the cultural function of the figure of the child antagonist during a specific time period and within a particular genre or medium? Is the cruel child simply linked to villainy more broadly, or is s/he portrayed in ways that highlight the cruelty and wrongdoing specific to childhood?

In this essay, I focus on the media interface between the so-called golden age of American horror comics (1948–1955) and the tabloid-style television news series Confidential File (KTTV, 1953–1958), which critiqued boys’ consumption of comic books, in terms of the representation of moral panic and public anxiety during the early years of the Cold War (Cohen [1972] 2002 ; Doherty [1988] 2002 ; Galloway 2012 ; Studlar 2013 ; Thompson 2009 , 2012 ; Trombetta 2010 ). More specifically, I expand upon the social and historical significance of the cruel child by investigating the representation of boyhood and criminality in cultural texts during the years 1948–1960. Starting with the horror comic book series Tomb of Terror (Harvey, 1952–1954), I examine the deep impact of Entertaining (or EC) Comics’ best-selling publications on the US cultural imaginary, while at the same time drawing attention to the performance of juvenile delinquency and moral panic in Confidential File , hosted by Paul Coates. I propose that the Cold War horror comic book underscores the intersectionality, rather than structuring antinomy, of boyhood innocence and criminality. Ultimately, the politics of anxiety performed in Tomb of Terror and Confidential File emphasizes the power and agency, rather than violence and savagery, of the cruel child by complicating the boundary between the normal and the pathological. 2

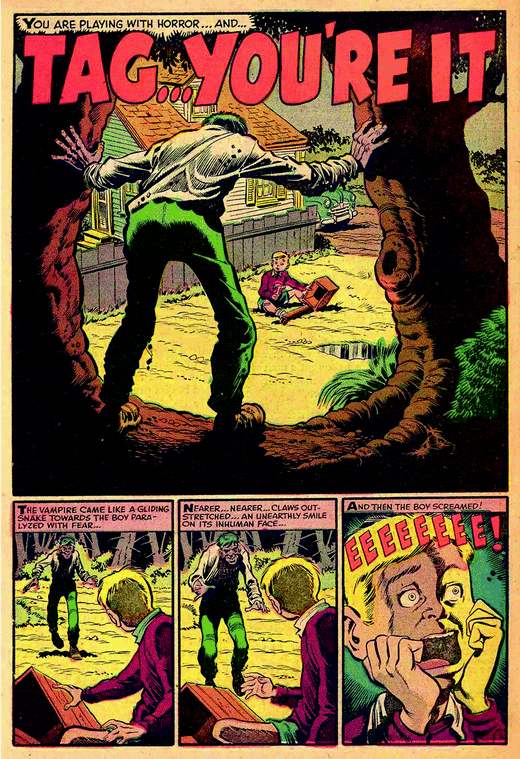

In the texts I have chosen, the performance of boyhood is conflated with the shocking representation of the cruel child. The figure of the child in the Tomb of Terror story “Tag … You’re It,” in addition to Confidential File , provides a spellbindingly “factual” report on Cold War America insofar as the child is constructed and made compatible with cruelty within a social and historical context that is defined by moral panic and public anxiety. In comparing these texts, it becomes apparent that the cultural function of the cruel child is underwritten by a vocabulary that is laden with the conjectural threat of crime and graphic narrative violence, in addition to the conservative and moralistic outrage of television news and political performance. In short, this is an essay about tracing a changing construction of the figure of the cruel child in comic books and television, one connected to larger social and cultural shifts that affected a vision of the USA in the postwar boom and beyond.

“Tag … You’re It” and the Performance of Boyhood and Criminality

In the Tomb of Terror story “Tag … You’re It,” the performance of boyhood and criminality is a dominant motif. Regarding the significance of Paul Coates’s narrative of boyhood to Cold War politics and beyond, the figure of the cruel child in “Tag … You’re It” is constructed according to a politics of anxiety that is connected to the Cold War in terms of paranoia and disenchantment. In what follows, I offer an extended plot summary of “Tag … You’re It” in order to explain how Coates’s reaction to Cold War comics is, ironically, more responsible for a new horror narrative about US boyhood than the comics he vilifies.

“Tag … You’re It”

The townspeople mobilize

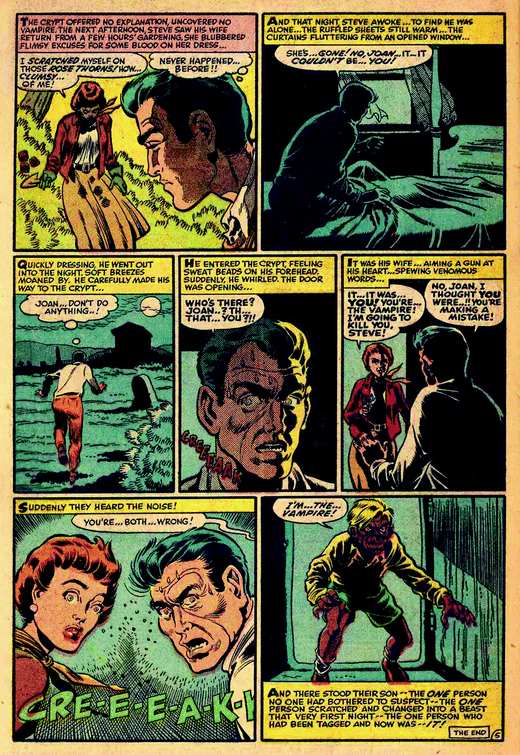

Another victim is discovered and paranoia sets in among the townspeople. The boy’s mother, Joan, discovers a pair of gloves covered in dried blood and a book about vampirism on her husband’s desk. She suspects that her husband, Steve, is a vampire. Steve, who does not possess Joan’s flair for deductive reasoning, suspects that his wife is a vampire based on her sharp nails and overly red mouth. “It couldn’t be …?!! Lord, tell me it couldn’t …!” he thinks. That night the vampire strikes again. Fearing for the safety of their son, Joan and Steve lock the door to Bobby’s room. Afterward, they set out to investigate a crypt, “a breeding place for the vampire.”

“I’m the Vampire”

“Tag … You’re It,” written by Howard Nostrand with artwork by Nostrand and Sid Check, was published in the July 1954 issue of Tomb of Terror (Harvey, 1952–1954) and marked the beginning of the end of the golden age of horror comics in the USA. Running for sixteen issues between the summers of 1952 and 1954, Tomb of Terror , like most American postwar crime and horror comics, perished in the wake of the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency hearings (April–June 1954) and the implementation of the Comics Code Authority (CCA). As David Hajdu points out in his book The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How It Changed America , many of the artists who worked for these publications suddenly found themselves unemployed, never to return to work in the comics industry (3–7).

According to William Gaines (1922–1992), publisher and co-editor of Entertaining (or EC) Comics and Mad magazine (1952–present), the CCA clauses that forbade the words “crime,” “horror,” and “terror” in comic book titles were a premeditated attack on his best-selling publications, including Crime SuspenStories, Vault of Horror , and Tales from the Crypt . In addition to the ban on “crime” and “horror” comic titles, the CCA prohibited the inclusion of classic horror archetypes such as the vampire, werewolf, and zombie. As stated by the Code for Editorial Matter, General Standards Part B5, “scenes dealing with, or instruments associated with walking dead, torture, vampires and vampirism, ghouls, cannibalism and werewolfism [sic ] are prohibited” (Nyberg). 4 Consequently, the figure of the cruel child in “Tag … You’re It” (a vampire that behaves like a zombie and can be killed like a werewolf with a silver bullet) exhibits a striking artistic innovation that is ultimately prohibited by the Comics Magazine Association of America (CMMA). 5 Many of the themes I explore in this essay are encapsulated in “Tag … You’re It,” including the figure of the cruel child as a gesture toward death and mortality, in which the themes of parental anxiety and moral panic are represented as a failure to save the child both before and after he has figuratively returned from the grave. In the case of “Tag … You’re It,” the child is portrayed in a way that illuminates the fears and anxieties of the Cold War nuclear family.

The Comics Code Authority Strikes Back

In the autumn of 1955, Paul Coates, like Bobby’s father, Steve, in “Tag … You’re It,” sought to expose the deleterious effects of popular culture on the youth of postwar USA. “In this comic book is a love story,” Coates remarks, “a boy and girl in love. They get married, and after an offensively lurid description, illustrated of course, of the couple’s wedding night, the book shows how the bride murders her husband by chopping his head off with an ax.” Pausing for dramatic effect, Coates reports, “This comic book describes a sexual aberration so shocking that I couldn’t mention even the scientific term on television. I think there ought to be a law against them. Tonight I’m going to show you why” (“Horror Comic Books”).

Coates, a journalist by trade, was the anchorman of the television news program Confidential File , a weekly fifteen-minute filmed documentary followed by a fifteen-minute live interview. Coates and Irvin Kershner, the director of the episode on horror comics aired on October 9, 1955, explored the evils of comic books and their effect on juvenile delinquency by way of a typical tough-guy moral lesson in the style of Joe Friday (Jack Webb) and the multimedia crime drama series Dragnet . 6 Following Coates’s hard-boiled introduction, the episode included a mock cinéma-vérité enactment of the harmful influence of comics, preceded by an interview with Senator Estes Kefauver. Kefauver, whose previous hearings into organized crime (1949–1951) made him a national celebrity, was a crusader against the rise of juvenile delinquency in the USA. Apparently unaffected by his exposure to horror comics, Kershner is best remembered as the director of Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back (1980), a milestone in genre film and proof of the lasting influence of popular culture and serial narrative media. 7

The standard way of thinking about men like Coates and Kefauver—and Bobby’s father, Steve—has it that the strict conservatism of Cold War America was acutely out of touch with the concept of adolescence both as a life stage and a determining factor in Hollywood’s postwar marketing strategy and theatrical production. In his book Teenagers and Teenpics: The Juvenilization of American Movies in the 1950s , Thomas Doherty argues that moviemakers since the 1950s, acknowledging the “rise of television and the collapse of the old [Hollywood] studio system,” focused on “the one group with the requisite income, leisure, and gregariousness to sustain a theatrical business. The courtship of the teenage audience began in earnest in 1955; by 1960, the romance was in full bloom” (2).

Channeled through Elvis Presley, James Dean, and the music to Blackboard Jungle (Richard Brooks, 1955), David Thompson ( 2009 , 2012 ) writes that “a sense of emotional anger and brooding violence” intersects with a “curdled humanism” that is featured in earlier films like Double Indemnity (Billy Wilder, 1944) and Sunset Boulevard (Billy Wilder, 1950) (The Big Screen 244). According to Thompson, “the peeling away of ‘Hollywood’ nonsense” eroded the economic and industrial bedrock of the USA (insurance and Hollywood), while at the same time paving the way for characters like Norman Bates in Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960) and the cultural capital of the postwar US adolescent (The Moment of Psycho 15). Driven by propriety and popular taste, the conflicting “desire for teenage dollars and dread of teenage violence,” Doherty argues, factored heavily in the representation of the cruel child onscreen, especially in the teenpic cycles (juvenile delinquency, horror, and clean teenpic) that followed shortly after Rock Around the Clock (Fred E. Sears, 1956) (64). 8

Furthermore, Doherty observes that the postwar US “teenage audience … expressed an unmistakable box office interest in the (real and imagined) explicitness beckoning from the screen. At the same time, however, there was a major reaction against these shocking new changes in … movies” (152). The appeal of rock and roll (Love Me Tender ; Robert Webb, 1957), drag racing (Rebel Without a Cause ; Nicholas Ray, 1955), and narcotics (The Cool and the Crazy ; William Witney, 1958) intersected with the moral, ethical, and spiritual values embodied by clean teen idols Pat Boone (Bernardine , 1957; April Love , 1957), Debbie Reynolds (Tammy and the Bachelor , 1957), Sandra Dee (Gidget , 1959) and Sally Field (Gidget ; ABC, 1965–1966)—values that were upheld and exploited by men like Coates, Kefauver, and Bobby’s father Steve in “Tag … You’re It.” Hence, the cultural function of the figure of the child as an icon of paranoia and disenchantment during the early Cold War illuminates not only the horror genre; it also exposes how cruelty was framed by the media interface between horror comic books, television news, and genre film.

The cultural function of the figure of the child during the early Cold War is indicative of what Alexander Galloway ( 2012 ) terms the “interface effect.” Regarding the juvenilization of the USA in the 1950s, the cruel child heralds what Galloway refers to as “a new socio-economic landscape” defined by “flexibility, play, creativity, and immaterial labor,” a new wave that threatens to take “over from the old concepts of discipline, hierarchy, bureaucracy, and muscle” (27). The ambiguity of boyhood and play in “Tag … You’re It,” by way of the consumption and circulation of horror comics and the above-mentioned teenpic cycles, upsets the prevailing distinction between innocence and criminality by illuminating “how cultural production and the socio-historical situation take form as they are interfaced together” (30). In other words, the figure of the child in Confidential File is constructed in such a way as to make it compatible with cruelty by means of a vocabulary that is laden with the conjectural threat of crime and graphic narrative violence, in addition to the conservative and moralistic outrage of television news and political performance. 9

Indeed, the figure of the cruel child in Confidential File is a figment of the imagination of Paul Coates, who, according to Doherty, tended “to mix psychological jargon with a moral tone sparking renewed interest in the mass media’s role in shaping young people’s behavior” (94). Albeit inadvertently, Coates’s moralistic outrage and political showmanship cultivated the box-office potential of the cruel child by promoting a narrative of generational conflict and the juxtaposition of societal order and individual havoc. Upholding the status quo, Coates emphasized the power and agency, rather than violence and savagery, of the youth of postwar America by exploiting the boundary between the normal and the pathological for shock effect.

The performance of boyhood and criminality in Confidential File stumbles upon a mode of narrative horror that is surprisingly progressive. 10 The depiction of boyhood in Confidential File is a report only insofar as “just the facts” are intended for shock value and the arousal of public opinion. More specifically, Coates presents a picture of criminality and youth culture that is consistent with, rather than opposed to, the conventions of the horror genre to the extent that, ironically, Confidential File exemplifies a mode of social and political activism, specifically the fight against patriarchal capitalism. Although Confidential File may seem extraneous, I propose that it illuminates the connection between the graphic and filmic representation of boyhood and criminality, in addition to the Cold War mentality of paranoia and disenchantment that Robert Warshow identifies as the “conception of human nature which sees everyone as a potential criminal and every criminal as an absolute criminal” (62).

For example, at the start of Confidential File , Coates encourages the viewer to “ask ten kids where they got the comic book they’re reading. Maybe one or two will tell you they bought it. The rest traded for theirs. They buy one book and they read ten. It’s wonderful economics, but unfortunately it means that ten times as many kids read books they should never even see.” Coates’s report on boyhood depicts the consumer behavior and reading habits of children as a type of viral outbreak, traversing the boundaries of class and race, while at the same time collapsing the potential for a more nuanced interpretation of class conflict and racial inequality within a paranoid narrative of criminality and moral degradation. “There are no economics or racial lines to the comic book threat,” Coates proclaims as the camera pans across a rickety domestic residence to an African American boy reading “The Human Hyena of Pirra” in Out of the Shadows #9 (July 1953), “they reach every strata. Kids read them in the north, and in the south” (“Horror Comic Books”).

A whip pan transitions between the country and the city, emphasizing the frenetic imagination of the imperiled child lost within a postindustrial wasteland. A white middle-class boy reads “Time to Die” in Dark Mysteries #16 (February 1954), and Coates’s jeremiad imagines a biblical flood of horror comics that children “read in living rooms in Dubuque and alleys in Manhattan, … in tree houses and tucked into their notebooks in classrooms.” A young Asian American boy runs across an abandoned lot strewn with auto parts and crawls inside the remains of a stripped automobile to read “Smoked Out” in Fight against Crime #20 (July 1954). “One glance is enough to tell you that this boy just got out of school for the day,” Coates observes. “And why shouldn’t he be happy? Until suppertime he can do anything he wants to do, he’s free. And he knows exactly how he’ll while away the hours. He’ll spend a nice quiet afternoon with a comic book. … He could have played baseball but he chose the comic book instead” (“Horror Comic Books”). In this quotation, Coates’s sarcasm exploits the binary opposition between the patriotic (baseball) and the pathological (comic books) while at the same time offering a rousing performance of boyhood and criminality for the television viewer.

According to Jim Trombetta, “Confidential File affords a good look at the [comic book] covers of real classics and even some notable interior spreads,” most of which are included in Trombetta’s book The Horror! The Horror!: Comic Books the Government Didn’t Want You to Read (86). Only recently, in edited collections like The Horror! The Horror! and Four Color Fear: Forgotten Horror Comics of the 1950s (2010), have EC and non-EC horror comics received the attention they richly deserve. Taking into account that EC represents a mere seven percent of the total 1950s horror comics output, titles like Out of the Shadows (Standard, 1952–1954), Dark Mysteries (Master Comics, 1951–1955), and Fight against Crime (Story Comics, 1951–1954) are provided with a rare opportunity in Confidential File to be studied and appreciated (Benson 6). Subsequently, Coates’s argument against the horror comic book as a medium of corruption is predicated upon the disclosure and remediation of an art form that has already been forced into obscurity. 11

Ultimately, the moral dispute of Confidential File addresses the fictionalized image of boyhood, lost innocence, and the imperiled American Dream. “The underlying hysteria of this episode of Confidential File ,” Trombetta writes, “isn’t really about comic books. … The airdate, October 9, 1955, is nearly a year and a half after Senator Kefauver’s subcommittee hearings on juvenile delinquency. The Comics Code is already in effect. … We have all been saved.” 12 Nevertheless, Trombetta adds, “Coates needs a thrill, and while he digs one up at last, it’s not as easy as it might have been. In fact, he must peek into what he conceives as the secret life of children to find it” (306). In contrast to the artists who lost their jobs as a result of the CCA, Paul Coates exploits the prohibition of horror comic books and, in the process, makes a valuable contribution to an art form that he claims to be fundamentally opposed to.

This is a point that is especially relevant to the cultural function of the performance of boyhood and criminality. The Cold War intervention of Confidential File , like the Salem witch trials (1692–1693) and Satanic Panic (1980–1990), is a narrative in which the desire to imagine the secret life of children activates a feeling of public anxiety that is wildly imaginative. The moral panic concept emerges from and exacerbates the conjectural threat of crime and graphic narrative violence, in addition to the conservative and moralistic outrage of television news and political performance. Borrowing from Stanley Cohen ([1972] 2002 ), the underlying hysteria of Confidential File ’s episode on horror comic books is communicated through the child as “a threat to societal values and interests” (1). 13 Hence, the juxtaposition of innocence and criminality affects the status of boyhood in cultural texts during the postwar boom by exploiting the antinomy between good and evil for shock effect. Like Bobby in “Tag … You’re It,” the image of the imperiled child in Confidential File is re-envisioned as a hideous public service announcement in which the youth of postwar USA, beyond the purview of adult supervision, are tainted by the scourge of juvenile delinquency. Correspondingly, the representation of boyhood and play as a game of violence and domination is a key theme that bridges the gap between the Cold War horror comic book and tabloid-style television news program.

Conclusion

The cultural function of the figure of the child in relation to cruelty is a vital aspect of the Tomb of Terror story “Tag … You’re It.” More specifically, the performance of boyhood and criminality is a dominant motif in “Tag … You’re It” and Confidential File , hosted by Paul Coates. This is an especially salient point when we consider that the cruel child, according to Coates, functions as an indicator or predictor for the apparent loss of power and prosperity in the USA during the Cold War. The vampire boy in “Tag … You’re It,” like the sadist in thrall to what Coates describes as “the sexy crime-worshipping violence of certain comic books” (“Horror Comic Books”) is, most intolerably, a figure who threatens the dominant ideology of bourgeois patriarchal norms, including monogamy, heterosexuality, and the nuclear family.

By the same token, the cruel child rebels against an idealized vision of postwar USA embodied by the clean teen idols Pat Boone, Debbie Reynolds, Sandra Dee, and Sally Field. Ultimately, “Tag … You’re It” and Confidential File exist within a time period that is founded upon a puritanical moral code; Bobby, in “Tag … You’re It,” is a child antagonist worthy of the vilification of Paul Coates. Yet the shock effect of “Tag … You’re It” points to something beyond morality. It is a fleeting glimpse of the interface between the postwar horror comic book and tabloid-style television news program. “Tag … You’re It” and Confidential File reveal the possibility of a broader intermedial history of the horror genre and the cultural function of the figure of the cruel child during the Cold War and beyond.

The reason that these texts are speaking to us all these years later is that the figure of the cruel child is one of the most compelling images in horror media. The cruel child is a figure who speaks to a sense of moral ambiguity that overturns the facile distinction between the metaphysical categories of good and evil. By complicating the difference between the concepts of innocence and criminality, the child has captured the popular imagination and proven that the embodiment of cruelty is central to the horror genre. In Confidential File , the secret life of boyhood is pathologized via the medium of television. Indeed, the only thing that is horrifying about children playing outside is the language of media (montage, voiceover, non-diegetic music). In order to support the rule of prohibition enforced by the CCA, Confidential File presents a pseudo-exploitation horror narrative saturated with moral panic and public anxiety. The 1954 Comics Code is translated into a horror screenplay enacted by the very talent it seeks to shield from the degrading effects of horror comic books. The moralistic outrage and political showmanship performed by Coates indicates how a political climate of conservatism and paranoia, generally associated with a broader cultural Puritanism, illuminates the connection between cultural production and the socio-historical situation. Regarding the cruel child, Paul Coates’s performance as the cold warrior and puritanical overlord is an artistic endeavor in its own right.

Contrary to what Paul Coates intended in Confidential File , the figure of the priceless child in need of protection from horror comic books exposes the false virtues of patriarchal capitalism and the nuclear family, the gendered arrangements of work and care, and the mythology of a golden age of socio-economic prosperity that is conducive to youth culture. Ultimately, Coates is confronted with the reality that the horror genre is at its best when it adheres to a position of resistance to the status quo and the belief that the boundaries between the normal and the pathological are to be enforced with extreme prejudice. As a result of Confidential File and the politics of anxiety during the early Cold War, the cruel child is speaking to us all these years later. Thanks to Paul Coates, the horror genre is alive and well.

Notes

-

1.

See Bohlmann and Moreland ( 2015 ), Lennard ( 2014 ), Lury ( 2010 ), Oates ( 1997 ), Petley ( 1999 ), Renner ( 2013 ), Staats ( 2014 ).

-

2.

The function of the figure of the child as a social and political meaning is one of the driving forces behind the horror film as a culturally relevant art form. It is also an indication of the moral ambiguity of the cruel child in popular culture. In his book The Normal and the Pathological , the prominent philosopher of science Georges Canguilhem (1904–1995) maintains that “every conception of pathology must be based on prior knowledge of the corresponding normal state.” At the same time, “the scientific study of pathological cases becomes an indispensable phase in the overall search for the laws of the normal state” (329).

-

3.

“Tag … You’re It.” Tomb of Terror , written by Howard Nostrand, art by Howard Nostrand and Sid Check. In The Horror! The Horror! Comic Books the Government Didn’t Want You to Read! , edited by Jim Trombetta (Abrams ComicArts 2010), pp. 85–89. All other quotes are from this source unless otherwise indicated.

-

4.

Unlike Tomb of Terror, Mad magazine endured the initial onslaught of the Comics Code thanks to Gaines’s decision to convert the publication to a black-and-white magazine format, to which the Code did not apply.

-

5.

As an alternative to government regulation, the CMMA opted to self-regulate the content of comic books in the USA. Similar to the Motion Picture Production Code (1930–1968), the CMAA represented a set of industry moral guidelines that limited creativity and artistic collaboration. Be that as it may, the deep cultural impact of horror comics during the postwar era affected a new wave of US horror filmmakers in the 1970s and 1980s. In the television documentary Tales from the Crypt: From Comic Books to Television (Chip Selby 2004 ), George A. Romero and John Carpenter readily acknowledge a debt to the horror comics of their youth. An admiration for the artwork of Jack Davis factors heavily in Romero’s use of Technicolor and widescreen composition in Dawn of the Dead (1978). Davis began freelance work for EC Comics in 1950, contributing to Tales from the Crypt, The Haunt of Fear, Frontline Combat , Two -Fisted Tales, The Vault of Horror, Piracy, Incredible Science Fiction, Crime SuspenStories , and Terror Illustrated . In her book Killer Tapes and Shattered Screens ( 2013 ), Caetlin Benson-Allott points out that the thematic “condemnation of both consumer culture and American racism” in Dawn of the Dead pays “homage to the overt visual sarcasm of 1950s horror comics, specifically Entertainment [sic] Comics’ Vault of Horror and Tales from the Crypt , which use parody to associate gore with progressive social critique.”

Moreover, narrative devices like the “just deserts” motif are critical not only to the postwar horror comic book but the modern horror film and Carpenter’s Halloween (1978) in particular. According to Carpenter, the just deserts motif in EC comics was a trope in which the criminal, at the end of the story, received their comeuppance—ironically, in the same way they delivered it to others. For example, in “Taint the Meat … It’s the Humanity!” (Tales from the Crypt #32, October–November 1952, artwork by Jack Davis), a mild-mannered butcher tries to boost profits by selling spoiled meat to his unsuspecting customers. After his plot is discovered, the butcher attempts to skip town, only to find that he has accidentally poisoned and killed his son with tainted meat, a crime that drives the butcher’s wife into a murderous rage. Picking up a kitchen knife, she stabs her husband to death. The final panel of the comic pictures the butcher’s wife standing behind a cooler filled with the body parts of her recently deceased husband, absentmindedly chanting “tainted meat?” Likewise, the just deserts motif is employed and recontextualized in Halloween when the ostensibly vanquished Michael Meyers, repeatedly shot and stabbed by Dr. Loomis and Laurie, falls from a second-story window only to escape into the night unharmed. The tenacity of the bogeyman archetype as a non-specific embodiment of terror is reinforced in the closing moments of the film through a series of subjective POV shots, accompanied by the atmospheric sound of breathing and the main theme of Carpenter’s musical score. At the end of Halloween , the killer and the camera return to the scenes of the crime; the criminal’s comeuppance is replaced by the killer’s nostalgic homecoming and the promise of further mayhem. Regarding the nostalgic value of the killer in the early teen slasher cycle, one of the original taglines for Halloween is “The Night He Came Home!” (Selby).

-

6.

Dragnet aired on NBC between 1949 and 1957 (radio); from 1952 to 1959, and 1967 to 1970 (television); and was released in theaters in 1954, 1966, and 1987 (film).

-

7.

Influences include the 1936 Universal serial Flash Gordon (Frederick Stephani), its sequel, Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe (Ford Beebe and Ray Taylor, 1940), and serial radio dramas from the 1940s. Flash Gordon appeared as the hero of a science-fiction comic strip originally drawn by Alex Raymond and first published on January 7, 1934.

-

8.

According to Doherty, the first European play dates of Rock Around the Clock in late 1956 coincided with “a rising crescendo of teenage violence. In England, police arrested more than ‘100 youths, boys, and girls’ driven to violence by the ‘hypnotic rhythm’ and ‘primitive tom-tom thumping’ of” the movie, “in what was called ‘the most impressive aftermath of any film ever showed in Britain.’ The queen herself requested a private screening to see what the fuss was about” (64).

-

9.

Accordingly, I embrace the work of Gaylyn Studlar and the idea that juvenation, or the medium of youthfulness, is a process linked to gender, genre, and “the taboo aspects of children’s display.” Bobby in “Tag … You’re It,” like most of the children I examine in this essay, complicates the boundaries between innocence and criminality, in addition to the normal and the pathological. As a result, the performance of boyhood and criminality is a key example of Studlar’s argument that “images of the young as a category of appeal” are determined less by age than the communication of youthfulness. The cruel child in Tomb of Terror and Confidential File , similar to the delinquent and clean teen idols mentioned above, represents what Studlar considers “a preoccupation with the boundaries of age and with the young.” As a stage of life and moral classification, the figure of the Cold War child exists across a range of historical and social awakenings and crises, from the work of Howard Nostrand and Sid Check to Paul Coates and Confidential File (1–2).

-

10.

According to Robin Wood, the progressive horror film is imbued with a sense of social and political activism, specifically the fight against patriarchal capitalism. Wood references Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left (1972), Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), and Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978) as examples of this trend. Horror in the 1980s, on the other hand, reinforces the dominant ideology, representing the monster as simply evil and unsympathetic, depicting Christianity as a positive presence, and confusing the repression of sexuality with sexuality itself. Examples include Craven’s Swamp Thing (1982), Hooper’s Poltergeist (1982), and Romero’s Creepshow (1982).

-

11.

Trombetta exposes Coates’s less than accurate timetable when he observes that by October 1955, trading was the only method of acquiring crime and horror comics that were no longer being published (86).

-

12.

According to Trombetta, the newly elected “czar” of the comic book business is “Charles F. Murphy, a former New York City magistrate, who polices crime and horror (and hates science fiction and E.C. comics)” (306).

-

13.

In his book Folk Devils and Moral Panics , Cohen argues that:

Societies appear to be subject, every now and then, to periods of moral panic. A condition, episode, person or group of persons emerges to become defined as a threat to societal values and interests; its nature is presented in a stylized and stereotypical fashion by the mass media; the moral barricades are manned by editors, bishops, politicians and other right-thinking people; socially accredited experts pronounce their diagnoses and solutions; ways of coping are evolved or (more often) resorted to; the condition then disappears, submerges or deteriorates and becomes more visible. (1)