Chapter 11

Understanding Change

Today, initiating new interactions is often more productive than generating new products, new forms, or new styles. Graphic designers who collaborate with people in other disciplines—architects, choreographers, linguists, mathematicians, chefs—are discovering that they can expand their practice beyond the confines of the conventional boundaries for their profession and still retain their distinctive competence. Truth be told, there are very few domains in which the input of graphic designers doesn't enhance the end result and elevate the conversation.

Richard Saul Wurman

The Architect of Understanding

Information Architects

by Richard Saul Wurman

1997

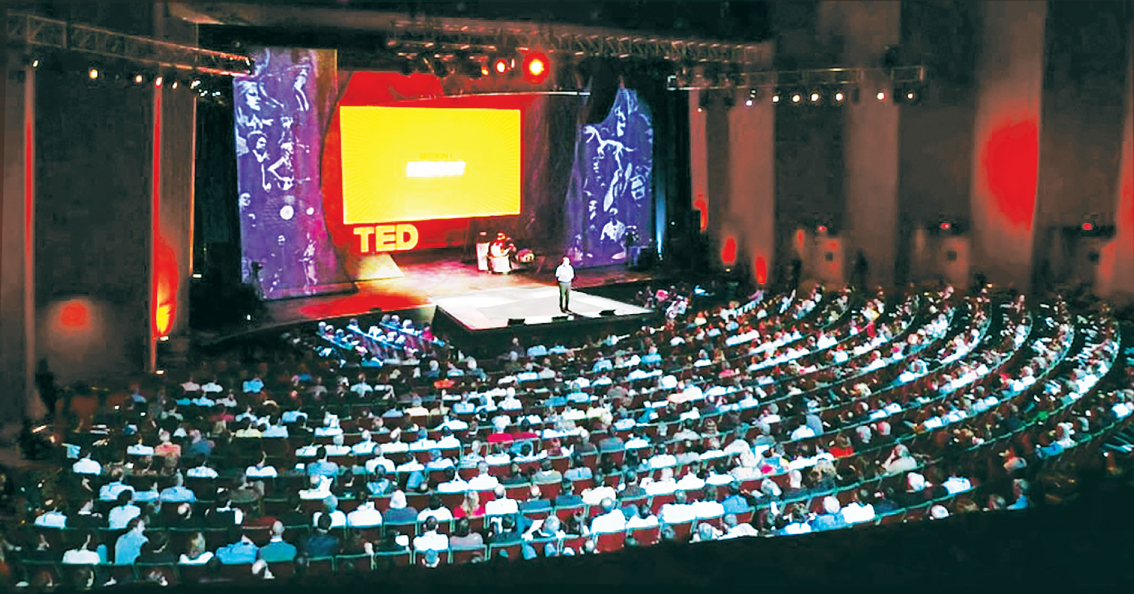

Back in 1984, when you put together your first TED conference, what was your objective?

All I was trying back then was to create a conference I would personally enjoy—one featuring people who intrigued me. I wasn't trying to “share” my interests with others, but rather satisfy my own curiosity. Granted, it was egocentric and self-serving. I just wanted my programs to be “good.” And they were.

My very first conference was amazing. Among the speakers were Frank Gehry, who wasn't famous yet; Steve Jobs, who made public for the first time three working prototypes of the Macintosh; Nicholas Negroponte, who announced the MIT Media Lab; and the president of Sony USA, who distributed shiny little disks—the first CDs anyone had ever seen. I wasn't trying to change the world—but my guests did!

I sold TED in 2003 to a gentleman who, unlike me, is trying to “change” the world. There is a fundamental difference between him, who wants to “do good”—and me, who wants to “be good” at whatever I happen to be working on.

Your mission might not be to change the world, but isn't it to make information more understandable?

I have written many books on the topic of “understanding”—too many titles probably: Understanding Healthcare, Understanding USA, Understanding Children, Understand Change & the Change in Understanding, and so on.

The Urban Observatory Exhibit San Diego

2013

Let me put it succinctly: Usually, to make things understandable, graphic designers illustrate words. They put pretty pictures on words. That's not what I suggest you do. You should use words when words are better; you should use pictures when pictures are better. And you should marry them both when that's better.

You were one of the pioneers of data visualization with your ACCESS books—graphically intelligent city guidebooks published in the 1970s. In fact, aren't you credited with coining the term “information architecture”?

Yes, however, people give me credit for a lot of things, but really my passion is to try to understand what it's like NOT to understand. That's all I ever do. I sell my ignorance.

But I cannot go to a publisher, or to anybody for that matter, and say: “Here is a topic that interests me, but I don't understand it. Can you give me money so that I can find out?” Needless to say, I would never get the money. That's why I generate my own projects.

My mission is not to make information more understandable. My mission is to go from not knowing . . . to not knowing. I never try to sell my expertise. In fact, rather, I sell my ignorance. When I am finished with a book or a project, it's over. It's done. I have no interest in it. I am on to the next thing—to the next thing that I don't know anything about.

And what is the “next thing” today?

There is a bunch of next things. Last year it was a conference format called “www,” in which presenters were paired in improvised dialogues. There is also my “Urban Observatory,” a new graphic initiative to compare information on urban centers, and something called “The Orchard of Understanding.” It's a lot to explain!

But my latest-latest project is called “555.” It's a series of conferences to try to satisfy my curiosity about the future. The format is: five cities, five speakers in each city, giving predictions for the next five years. I am 78 years old; what am I curious about? I am curious about “next”—next being the next 5 years, not the next 10, 15, or 50 years.

What will be the format?

I'll improvise, as I always do in these situations, but within an extremely well-curated nebula of visual information, including cartography, diagrams, interactive maps, and so on. We'll start in Australia and go around the world. Then Berlin, Singapore . . . and within a year, all 25 speakers will have had improvised conversations with me about what we can expect in the next five years.

You improvise! You are fearless!

I am absolutely comfortable saying whatever is on my mind. I feel that there is no filter between my brain and my mouth. Now, that looks like being fearless. Maybe it's because I am primitive, immature, childlike, egomaniacal, not too bright. Maybe I am like the Emperor Who Has No Clothes.

I don't know another way to be— but I can tell you, it works well. I am successful.

Petrula Vrontikis

Creating Interactions

UCLA Extension Fall Quarter Poster

Designer: Petrula Vrontikis

2013

Why is Southern California a great place to practice design?

Los Angeles has been primarily an entertainment industry town, but designing for that sector has become intolerable and no longer lucrative. However, fresh, dynamic tech companies have created Silicon Beach in the Santa Monica and Venice areas. Pasadena is aggressively fostering innovative companies and venture capitalists. This has cultivated a start-up culture that's energizing young entrepreneurs to create their own products and services. It's a very exciting time to be a designer here. It's been terrific to see so many pioneering firms flourish here.

How has the culture of Los Angeles influenced your design sensibility?

To some, it may sound trivial, but the great weather here helps me keep a sunny disposition and a clear outlook. I'm a seriously happy person in a seriously lovely place. Plus, Los Angeles attracts wildly talented young people who choose to start their careers in graphic design. It's made teaching at Art Center College of Design so deeply meaningful.

You are a teacher, a lecturer, and a writer as well as a graphic designer. Is your love of words related to your love of typography?

Yes, absolutely. I love the power that letterforms have to both clarify and abstract messages and meaning. I love the play of words in both writing and design.

In your spare time, you are an underwater photographer. Back on dry land, you “swim” between various design cultures. Is transmedia graphic design a little bit like scuba diving?

Scuba diving is certainly a cross-media multisensorial experience! To survive, you must be agile—equipped with everything required in an ever-changing environment. An accomplished diver attains something called neutral buoyancy—a kind of mastery of the underwater “formal skills” where you float weightlessly without effort, neither sinking nor rising. The equivalent for a transmedia graphic designer could be called “creative ambidexterity,” which combines the skills, equipment, and mind-set for her/him to swim confidently between print, digital, dimensional, interactive, motion, and environmental media.

The Changing Landscape of Philanthropy

Designer: Petrula Vrontikis

Photography by Susan Burks

2013

For both the designer and the diver, this toggling becomes second nature, so we no longer have to think about barriers anymore. We become free to make left turns, travel upside down and sideways—becoming fearless and playful. Interacting with a well-crafted Transmedia project feels spontaneous and delightful.

Processing—the software—can generate incredible visuals. It's critical for students to immerse themselves in it (the underwater metaphor is unintended). In your evaluation, is generative design an important new discipline—and why?

Generative design is so powerful that I believe it will enable an entire generation of young designers to create motivations and circumstances that could never have been imagined. Its power as a medium to engage and interact with both individuals and communities is only in its infancy. Graphic designers are at the forefront of this unique expressive science experiment. It's an entirely new language that transcends cultural and communication boundaries.

What would you say is the main advantage of being a woman in the design field?

I believe women have greater access to empathy—which is the successful designer's secret weapon. Empathy energizes the design process, builds trust, and connects people to ideas emotionally.

Many women designers and educators I know inspire others and bring meaning to what they do personally and professionally. It pleases me to see women in more leadership positions than ever before. Attributes considered “female” seem to be the emerging keys to effective creative leadership.

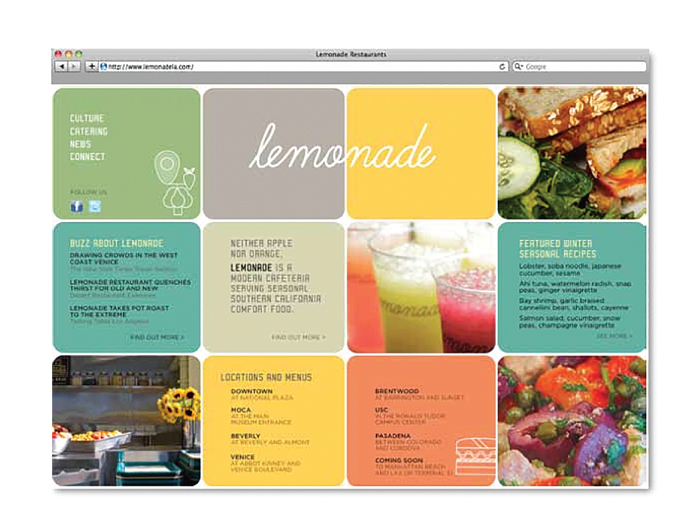

Lemonade Restaurant Website

Designer: Petrula Vrontikis

2013

Lemonade Restaurant Signage at LAX Airport

Designer: Petrula Vrontikis

Photography: Bill Brown

2011

Erik Adigard des Gautries

The Experience of the Information

Venice Architecture Biennale U.S. Pavilion

Designer: Erik Adigard

Studio: M-A-D

Art Director: Erik Adigard

2012

I think of you as someone who “curates” projects at the boundaries between emerging medias. But how do you describe what you do?

Our profession is full of ambiguities, and that is perhaps where the notion of “curating” might often be more relevant than a mere focus on typography, imagery, and other core graphic design functions. At the end of the day, our job is to help bring the ventures of others into specific parts of the world. These specificities demand that we be adaptive, accurate, and relevant to cultural and technological conditions. For the last two centuries, technology has been the driver of culture, with designers as tentative catalysts to keep it on a constructive track.

You relish projects involving complexity, like branding IBM software and redesigning their icon systems. Only two or three people on the planet really understand what you are trying to explain. Is it fun?

Branding IBM software was an epic and extremely interesting assignment, and a puzzle to tackle in that we had to create a cohesive system for five software initiatives that thousands of IBM designers could easily apply to communications, ranging from websites to packaging and exhibits. The original brand architecture of IBM software was dated, messy, full of meaningless brand gestures, and expensive to maintain. We had written a short letter to raise our concern: It influenced them to include M-A-D in the competition for the rebrand campaign.

You are a maven when it comes to abstract thought. What's your secret?

I don't buy the pretense of “design thinking” but do believe that thinking is inherently a part of design, as abstraction is part of thinking, even if necessarily complemented with context and objectives. My time studying semiotics and linguistics in Paris did help to develop an analytical mind, but I also am inspired by and learn from others with critical thinking skills: architects, sociologists, journalists, philosophers, theorists, and so on. Much of my thinking is the outcome of due process observations and interpretations. In that sense, it is more a craft than an art and more a matter of influences than one of instinct.

You said once that graphic design can help us “reframe the information that matters most.” In your work, the information that matters most is often the experience of the information. Do you agree?

That is such a great way to put it! I am beginning to surrender to the idea that in this world, “experience” matters more than information. I mean this in two ways. First, experience can be a meaningful sensorium of ideas, some poetic and others empirical, but mostly this is an artistic point of view, and second, with interface design user experience factors are at the core of our practice yet are meant to be transparent and at the service of information.

Chapter 50: AirXY Venice Architecture Biennale

Designers: Erik Adigard, Chris Salter

Studio: M-A-D

Art Director: Erik Adigard

2008

There is a striking difference between your 2008 and your 2012 Venice Architectural Biennale installations. The first one was highly technological, while the second one only used paper shades and pulleys. Were you trying to make a point?

My 2008 Venice Biennale installation was a creative commission—an experimental design exploration about media and the environment in all its dimensions. It was conceived as a physical and emotive sensorium, with sounds, sensors, lights, rhythms, flows, and even an atmosphere. The use of sensors, fog, a strobe, and a vertical projection gave the whole a peculiar sculptural quality.

Spreads from Wired Magazine (1993–2000)

Designers: Erik Adigard, Patricia McShane, Philip Foeckler

Studio: M-A-D

Art Director: Erik Adigard

1993–2000

In contrast, the 2012 U.S. Pavilion installation was a commission from the State Department, whose concern was information more than formal expressions. The curator, Cathy Lang Ho, the Guggheneim's David Van Leer, and Freecell architects also played a role in the interactive analog approach. One of my key contributions was to set the massive contextual information on the floor below the visitors and the 124 projects hanging from the ceiling. The simple interaction, combined with the idea of displaying the entire body of information, was a gamble enthusiastically embraced by the visitors and the Biennale judges.

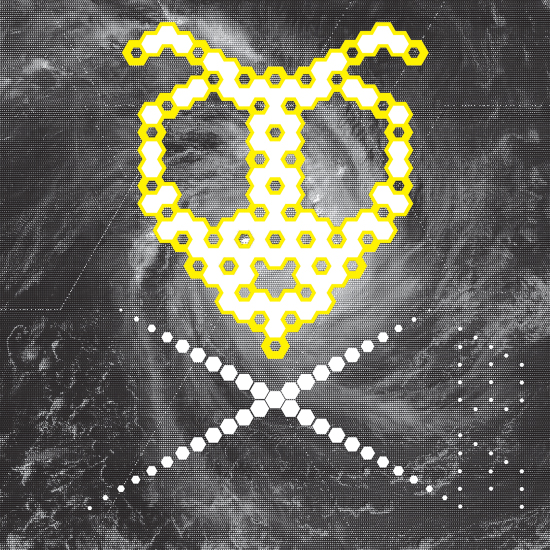

AGI Save the Bees Poster

Designer: Erik Adigard

Studio: M-A-D

Art Director: Erik Adigard

2010

You always work in network, with designers, architects, researchers, editors, programmers, and so on. Is your role in the team that of a “cultural mediator”?

Architects, writers, programmers, composers, theorists, curators, and other experts have played an important role in M-A-D's evolution in bringing their distinct perspectives. These are usually complementary, but sometimes they introduce creative disconnects, which is when the big questions are raised. Regardless, the outcome is sure to be surprisingly interesting. The grass is always greener on the other side, yet learning from others can result in ending back on your own turf!

Véronique Marrier

Graphic Design as a Cause

L'épreuve du temps, Graphisme en France

Publisher: CNAP

Graphic Designers: Léa Chapon, Mytil Ducomet/Atelier 25

2011

Can you tell us about your work so far?

Right out of graduate school, I worked in a gallery in Bordeaux, Galerie 90 degrés, an art space specializing in graphic design. I was creating exhibitions and events, doing everything from finding sponsors, curating collections, booking speakers, and supervising the design of catalogues. In 2002, I worked in the press office of the contemporary art museum of Rochechouart, a chateau in the Southwest of France that is home to an important archive of the work Raoul Haussmann—about 700 pieces, including collages, photograms, and experimental films. Two years later, I got an assistant position at the Ministry of Culture, where I had an opportunity to develop a series of cultural publications on the theme of graphic design.

Do you now have an opportunity to help shape government policies toward graphic design?

In France, graphic design is not a profession as much as it is a form of social, political, or philosophical engagement. The concept of official “policies” doesn't exist. The way I can help shape the future of graphic design in France is by being “engaged” myself on a number of fronts. My “causes,” if you want, include issues of language, the role of the new digital tools in defining how we communicate, the history of graphic design, and contemporary French typography.

Were you ever tempted to become a practicing graphic designer?

I am not a “practicing” graphic designer; however, “practicing” graphic design is exactly what I do! I “practice” by being an actor in the field, by creating opportunities for events, conferences, publications, acquisitions, proposals, and research projects. My “practice” consists in developing, analyzing, decrypting, interpreting, curating, art directing, managing, and promoting. All those different activities are what most graphic designers do today on a daily basis. The profession is no longer just about communicating specific ideas or messages—it is the coming together of various strategic pursuits having to do with visual expression.

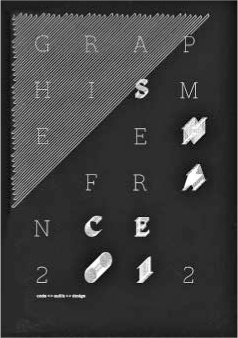

“<code><outils><design>”

Graphisme en France

Publisher: CNAP

Graphic Designers: Guillaume Allard, Johann Aussage, Vanessa Goetz/Pentagon

2012

From your point of view, what is the main contribution of graphic designers to the digital culture?

I am glad you asked this question because graphic designers have a very special talent: They think from the top down rather than from the bottom up. They come up with ideas that are all-inclusive rather than deductive. In other words, they have a capacity for integrated thinking.

Les Graphistes Associés Group Show

Galerie 90 degrés, Bordeaux

1996

That's why the digital age is the age of graphic designers! The merging together of experimental techniques involving visualizing, processing, computing, coding, scaling, and modeling comes naturally to them. If I give a graphic designer a brief for a publishing project, for instance, he'll turn it around on its head and come up with something totally unexpected. The technological component is just one of the many factors a graphic designer will incorporate in order to be truly creative. By “creative” I mean inventive, uninhibited, willing to propose a different world altogether.

How do you define your mission as a government-appointed advocate for graphic design?

I want to help define graphic design as a “practice.” I want clients, patrons, and users to think of it as a discipline for taking advantage of new opportunities and technologies, but also as a chance to reimagine how society functions. Because of the phenomenal number of innovations today, graphic designers are no longer limited by technology. Their unique experience, their personal vision, and their particular history are just as much part of their métier as their proficiency when using this or that software. Today, you experiment—for better or for worse. You take chances. You come up with hybrid solutions. You collaborate with unlikely partners. You work without safety nets.

Signalétiques, Graphisme en France

Publisher: CNAP

Graphic Designers: Anna Chevance, Mathias Reynoird/Atelier Tout va bien

2013

It sounds exciting—but how do you keep it all together?

Paradoxically, the new generation is incredibly disciplined, intellectually. As I mentioned earlier, the credit for this renaissance goes to French design schools. In the last decade, they have required that all students write elaborate research papers before they can graduate. Design history and criticism are now part of the curriculum. By the time they hit the job market, young graphic designers are not only creatively mature and technologically savvy; they are also better informed than their potential employers and less isolated culturally. I love working with them: They are a very articulate group.

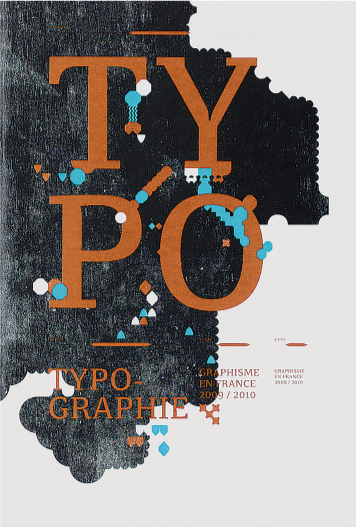

Typographie, Graphisme en France

Publisher: CNAP

Graphic Designers: Capucine Merkenbrack and Chloé Tercé/ Atelier Müesli

2010