3

TRAINING PROGRAM COMPONENTS

THERE IS AN ALL-TOO-COMMON misconception that one can prepare sufficiently for a marathon by simply running three days per week, provided one of those days includes a grueling 20-mile (or more) long run. That sounds simple, but the truth is that there’s a lot more to successful preparation than that. All runs are not created equal, and the long run, while key, is merely one component of a larger system that prepares you for success in the marathon distance.

The Hansons program has become known for the “16-mile long run” and a six-day-per-week running schedule that includes several types of workouts. This has sometimes been perceived as renegade when compared with status quo programs on the market, and some runners have had their doubts when we promise they’ll PR with our program. In fact, in the first edition of this book, we shared the story of Kevin Hanson’s wife performing marvelously using our method, albeit all the while intending to prove the method wrong. Since then, I’ve gotten similar e-mails, with runners who had been fired up to write a scathing “I told you so” instead thanking us for their PR and confessing that they never should have doubted the process. I don’t write these stories to gloat, but rather to show by example that there is more to successful marathon training than a few runs a week plus a long run. And while people tend to have laser focus on our 16-mile long run, they really have to embrace the whole picture of what the method entails.

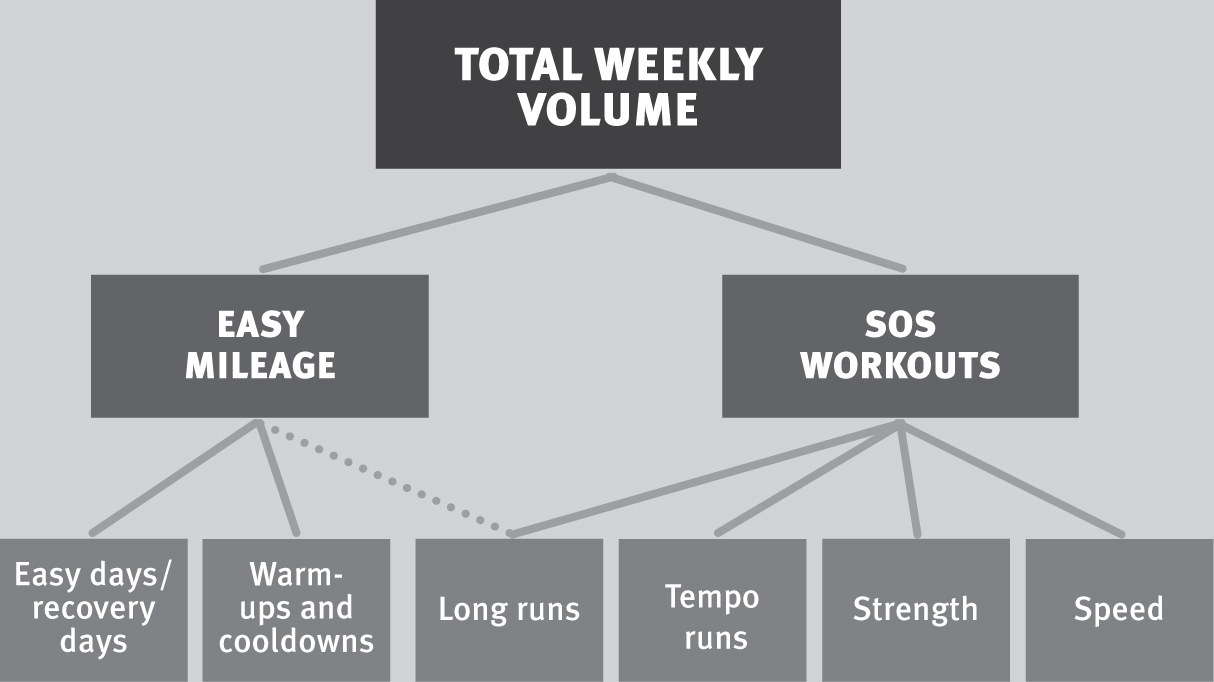

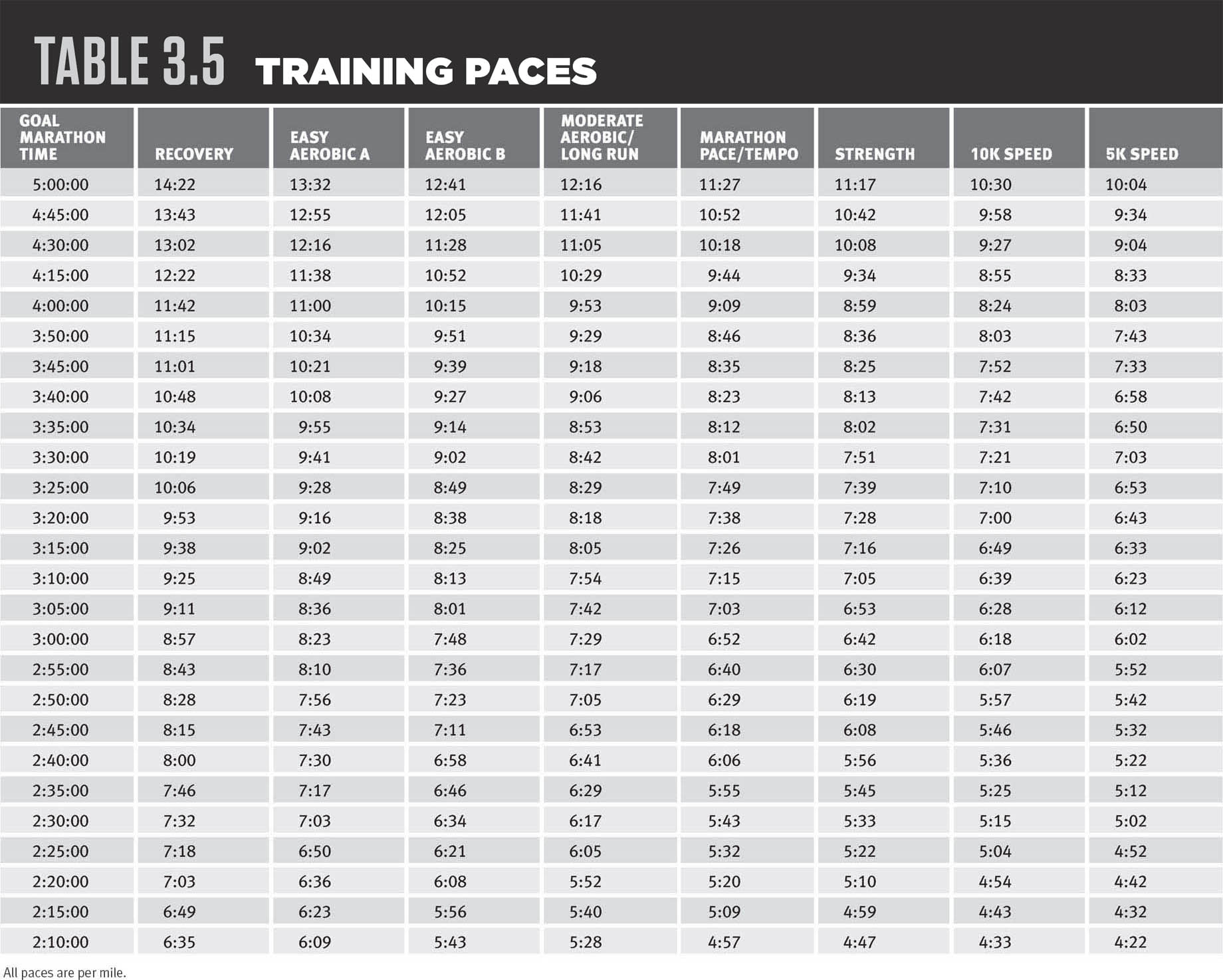

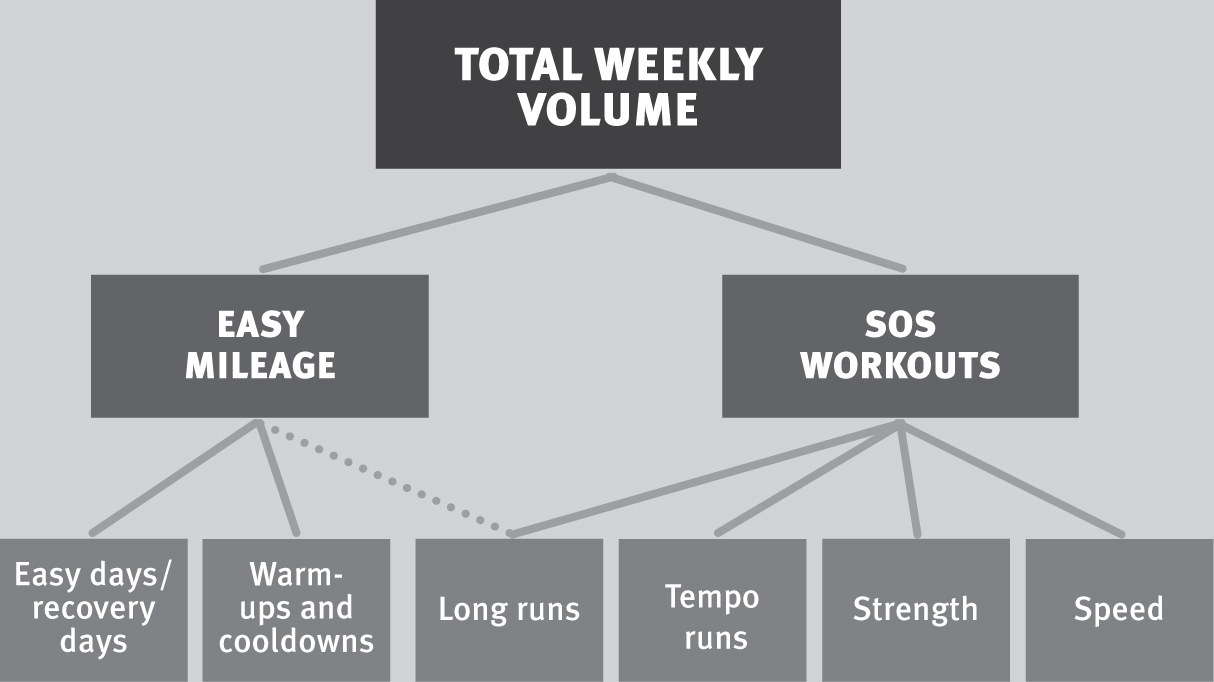

In this chapter, we will dissect our training schedules, considering the various components that make up our Just Finish, Beginner, and Advanced Programs. Runs are organized in one of two categories: Easy Days and Something of Substance (SOS) workouts. The SOS workouts include long, speed, strength, and tempo runs. (See Figure 3.1 for a breakdown of weekly mileage by workouts.) By varying the training plan from one day to the next, you train different bodily systems, all working in concert to optimize your marathon potential.

FIGURE 3.1 WEEKLY MILEAGE BREAKDOWN

This chart shows the breakdown of weekly mileage. Long runs are under SOS, because by definition they require more effort than a regular easy day. However, they are run at submarathon pace and could be defined as easy.

The basis for this approach stems from the overload principle, which states that when the body engages in an activity that disrupts its present state of homeostasis (inner balance), certain recovery mechanisms are initiated. As we discussed previously, different stresses work to overload the system, stimulating physiological changes. These adaptations, in turn, better prepare the body for that particular stress the next time it is encountered. This is where the principle of cumulative fatigue, which underscores our entire training philosophy, comes in. Cumulative fatigue is all about challenging the body without reaching the point of no return (overtraining).

Easy Running

Misconceptions abound when it comes to easy running. Such training is often thought of as unnecessary filler mileage. Many new runners believe that easy days can be considered optional, as they don’t provide any real benefits. Don’t be fooled: Easy mileage plays a vital role in a runner’s development. That’s good news because it means that not every run needs to be a knockdown, drag-out experience. Easy runs dole out plenty of important advantages without any of the pain by providing a gentler overload that can be applied in a higher volume than SOS workouts. This keeps the body in a constant state of slight disruption, helping to prevent injuries while simultaneously forcing your body to adapt to stress to increase fitness.

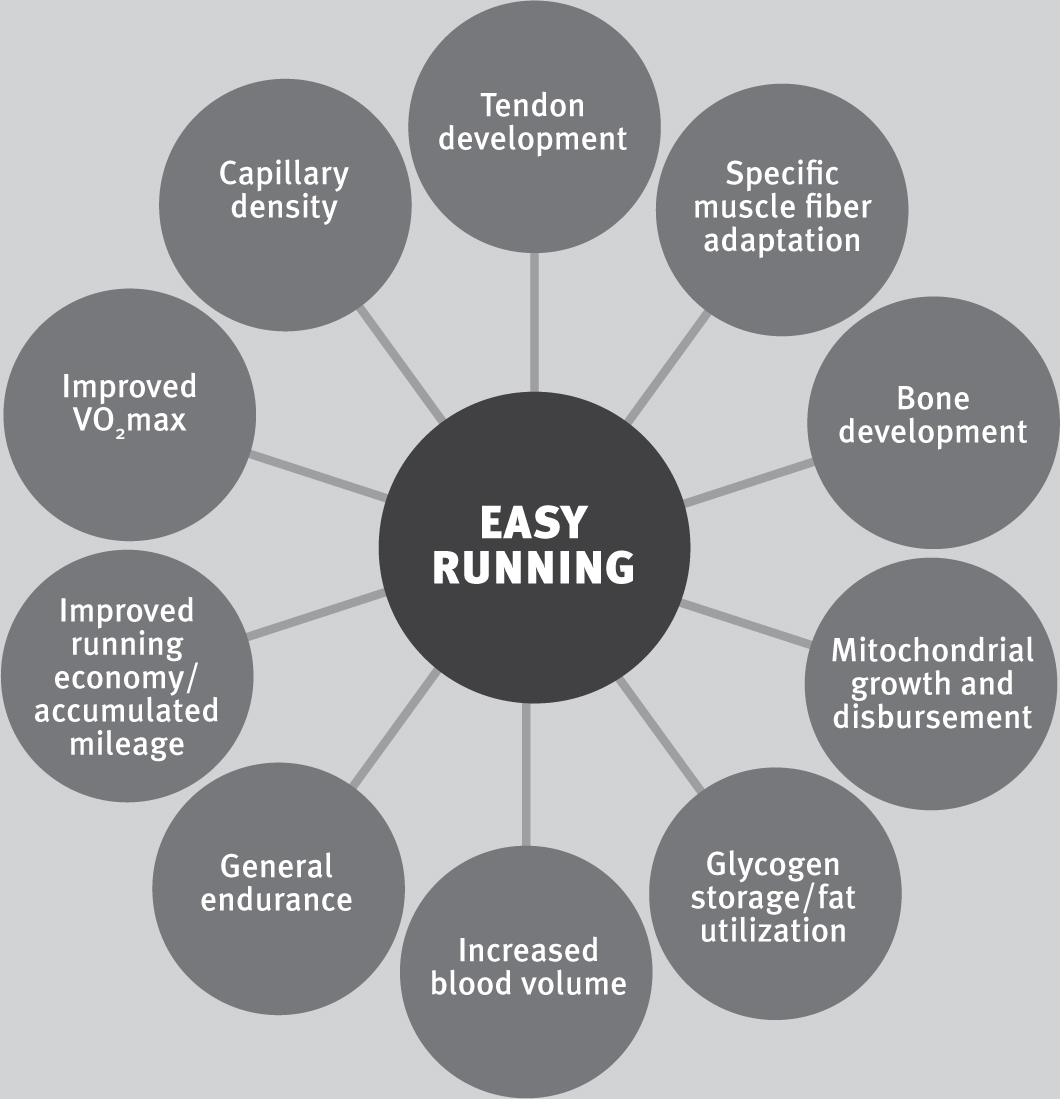

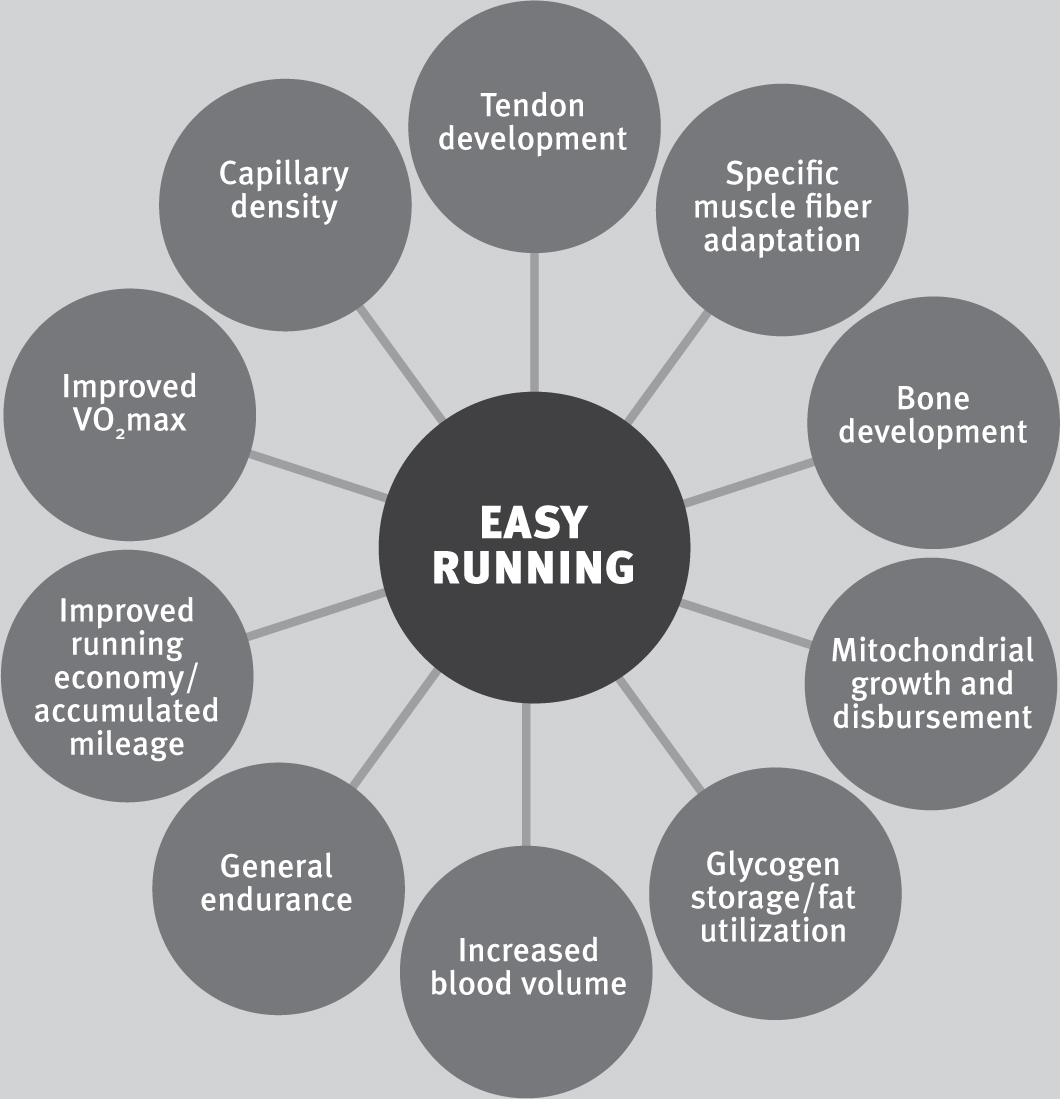

In the Advanced Program’s peak week, we prescribe a ceiling of 63 miles in a week. Looking closer, 31 of those miles, or 49 percent, are classified as easy. Figure 3.2 provides justification for why nearly half of your weekly mileage is devoted to this type of training. To understand why easy running is important, you must consider the physiological adaptations that it stimulates in muscle-fiber development, energy utilization, capillary development, cardiovascular strength, and structural fitness.

FIGURE 3.2 EASY RUNNING BENEFITS

Check out all the benefits that occur with easy running. Still think easy running is junk mileage?

THE PHYSIOLOGY OF EASY RUNNING

When considering why easy running is important, look at what it does for your muscle fibers. As discussed in Chapter 2, while the number of slow-twitch fibers you are genetically endowed with will ultimately define your potential as a marathoner, training can make a difference. Easy running recruits a whole host of slow-twitch fibers because they have a lower “firing,” or contraction, threshold than the more powerful fast-twitch fibers. Like any other muscle, the more they are used, the more they develop. Along with resistance to fatigue, slow-twitch muscles can be relied upon for more miles so that the fast-twitch muscles are not fully engaged until down the road. In the end, easy running helps to develop slow-twitch fibers that are more fatigue resistant and fast-twitch fibers that take on many of the characteristics of the slow-twitch fibers.

Plus, the more slow-twitch fibers you have, the better you’ll be prepared to use fat for energy. We now know this is a very good thing because the body contains copious amounts of fat to burn and only a limited supply of carbohydrates. The greater length of time you burn fat, rather than carbohydrate, the longer you put off glycogen (carb) depletion and an encounter with the dreaded wall. When you run at lower intensities, you burn somewhere around 70 percent fat and 30 percent carbohydrate. With an increase in pace comes an increase in the percentage of carbohydrate you burn. Your easy running days serve as catalysts to develop those slow-twitch muscle fibers and consequently, teach your body to burn fat instead of carbohydrates. Slow-twitch fibers are better at burning fat than fast-twitch fibers because they contain larger amounts of mitochondria, enzymes that burn fat, and capillaries.

In response to the need for fat to provide the lion’s share of the fuel for training, the mitochondria grow larger and are dispersed throughout the muscles. In fact, research has indicated that just six to seven months of training can spur the mitochondria to grow in size by as much as 35 percent and in number by 5 percent. This benefits you as a runner because the higher density of mitochondria works to break down fat more effectively. For instance, if you burned 60 percent fat at a certain pace a year ago, training may have increased that percentage to 70 percent. This is one of the many improvements training will elicit.

Thanks to easy running, your body will also see an uptick in the enzymes that help to burn fat. Every cell in your body contains these enzymes, which sit waiting to be “turned on” by aerobic activity. No pills or special surgeries are needed: This is simply your body’s natural way of burning fat. These enzymes work by making it possible for fats to enter the bloodstream and then travel to the muscles to be used as fuel. With the help of the increased mitochondria and fat-burning enzymes, the body utilizes fat for a longer period of time, pushing back the wall and keeping you running longer.

Capillary development is another benefit of easy running. Since running requires a greater amount of blood to supply oxygen to your system, the number of capillaries within the exercising muscles increases with training. After a number of months of running, capillary beds can increase by as much as 40 percent. It should also be noted that the slow-twitch fibers contain an extensive network of capillaries compared with the fast-twitch fibers, supplying those slower fibers with much more oxygen. As the density of capillaries increases throughout those muscles, a greater amount of oxygen is supplied in a more efficient manner to the muscles.

Easy running also results in a number of adaptations that happen outside the exercising muscle. As you know, your body requires more oxygen as it increases workload. The way to deliver more oxygen to your system is to deliver more blood. With several months of training, much of which is easy running, an athlete will experience an increase in hemoglobin, a.k.a. “the oxygen transporter,” in addition to a 35–40 percent increase in plasma volume. This increased volume not only helps deliver oxygen, but also carries away the waste products that result from metabolic processes.

Easy running also creates certain structural changes to your physiological system that you’ll find advantageous for good marathoning. But none of these adaptations makes much difference if there isn’t a good pump to move all of this blood and oxygen through the system. Just like skeletal muscle, the heart gets stronger with exercise. More specifically, the heart’s left ventricle increases in size and thickness, providing a bigger chamber to pump more blood from the heart to the arterial system. This gives the heart a break, as it won’t be required to beat as often to deliver the same amount of blood, regardless of rest or exercise intensity. If you compare your heart rate from the beginning of a training cycle to the end, you’ll be surprised by how much lower it can be. Again, this means that your system is becoming more efficient.

Another major physiological adaptation comes from within the tendons of the running muscles. As you may be aware, the body lands at a force several times the runner’s body weight, and the faster you run the greater that force becomes. The resulting strain on tendons and joints, applied gradually through easy running, allows these tendons to slowly adapt to higher impact forces to later handle the greater demands of fast-paced running.

Collectively, the adaptations stimulated by easy running prompt a higher VO2max, anaerobic threshold, and running economy. While fast anaerobic workouts provide little improvement in the muscles’ aerobic capacity and endurance, high amounts of easy running can bump aerobic development upward by leaps and bounds. Whether you’re looking to strengthen your heart, transport more oxygen to the working muscles, or simply want to be able to run longer at a certain pace, all signs point to including high amounts of easy running in your training.

Metabolic Efficiency 101 and Easy Running

Metabolic efficiency (ME) is a popular buzzword, but what does it really mean? It is basically the body’s ability to utilize its storage of fat and carbohydrate at the proper times. As it relates to our purposes, ME is an important measure of how well we burn fat and save carbohydrate at higher and higher intensities. In brief, the more metabolically efficient you are, the more fat you can utilize across the spectrum of paces.

Poor metabolic efficiency results in the body processing carbohydrate in higher amounts at lower intensities. This is the opposite of what we want for optimal marathon performance. Poor ME will ultimately limit our ability for prolonged running at even moderate paces because carbohydrate stores are depleted much more quickly than fat.

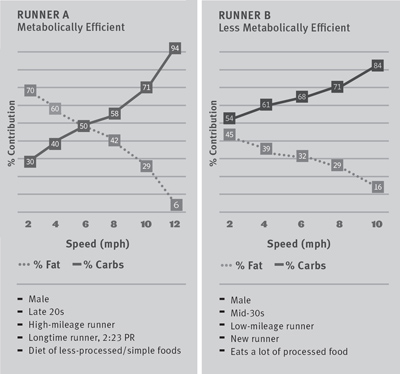

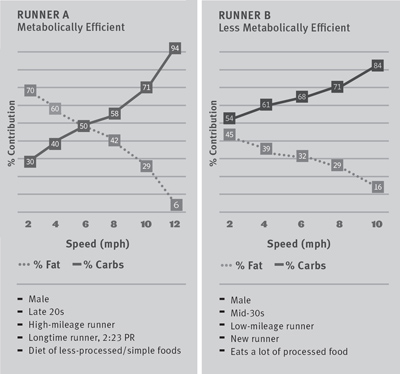

Figure 3.3 shows the metabolic efficiency of two very different athletes, with data taken during their VO2max tests. The figure showcases the relationship between poor ME and the onset of early fatigue. With Runner A, we see a textbook example of what good fueling looks like. Early on, during light intensity, he is burning primarily fat. As intensity increases, his reliance on carbohydrates increases. By the end of the test, he is running at VO2max effort and using almost all carbohydrate as his fuel source. Runner B illustrates a very different scenario. He is not as well trained and works out sporadically. The result of that lack of aerobic training is significant because we see that right away, at the lightest intensity, he is already relying on carbohydrate as a significant fuel source. As he approaches and surpasses marathon pace and moves into greater intensities, that number only increases. In sum, Runner A is preserving carbohydrate, while Runner B is burning through them at a high rate, even at marathon pace. The result for Runner B is that he will need to take in exorbitant amounts of carbohydrate to supplement what is being lost, or be forced to slow down from his goal pace.

FIGURE 3.3 METABOLIC EFFICIENCY OF TWO ATHLETES

How do easy runs fit into this?

Studies show that easy runs help runners develop ME. One study looked at the rate of fatty acid mobilization and fat usage as exercise intensity increased. The study showed the usage of fat versus carbohydrate after 12 weeks of endurance training. At 64 percent VO2max, the subjects increased their fat usage from 60 percent to 65 percent of the fuel contribution. This may not seem like a huge increase, but think of it like this. Say you burn 100 calories per mile, and 40 calories of those come from carbohydrate stores. With improved ME, you burn 35 calories per mile worth of carbs. That’s a difference of 5 calories, which over 26.2 miles, is about 132 calories of glycogen saved. Divide that by 35 calories and you get 3.79. That’s almost 4 more miles that you could run without taking any extra calories in through gels, sports drink, or other supplements.

Looking at ME and this study shows us that 12 weeks of endurance training at intensities of 65–85 percent of your VO2max promotes big increases in the ability to use fat as a fuel source. It just so happens that 65 percent is right around the effort that your easy runs will be at.

Easy runs are junk miles? Far from it.

EASY RUNNING GUIDELINES

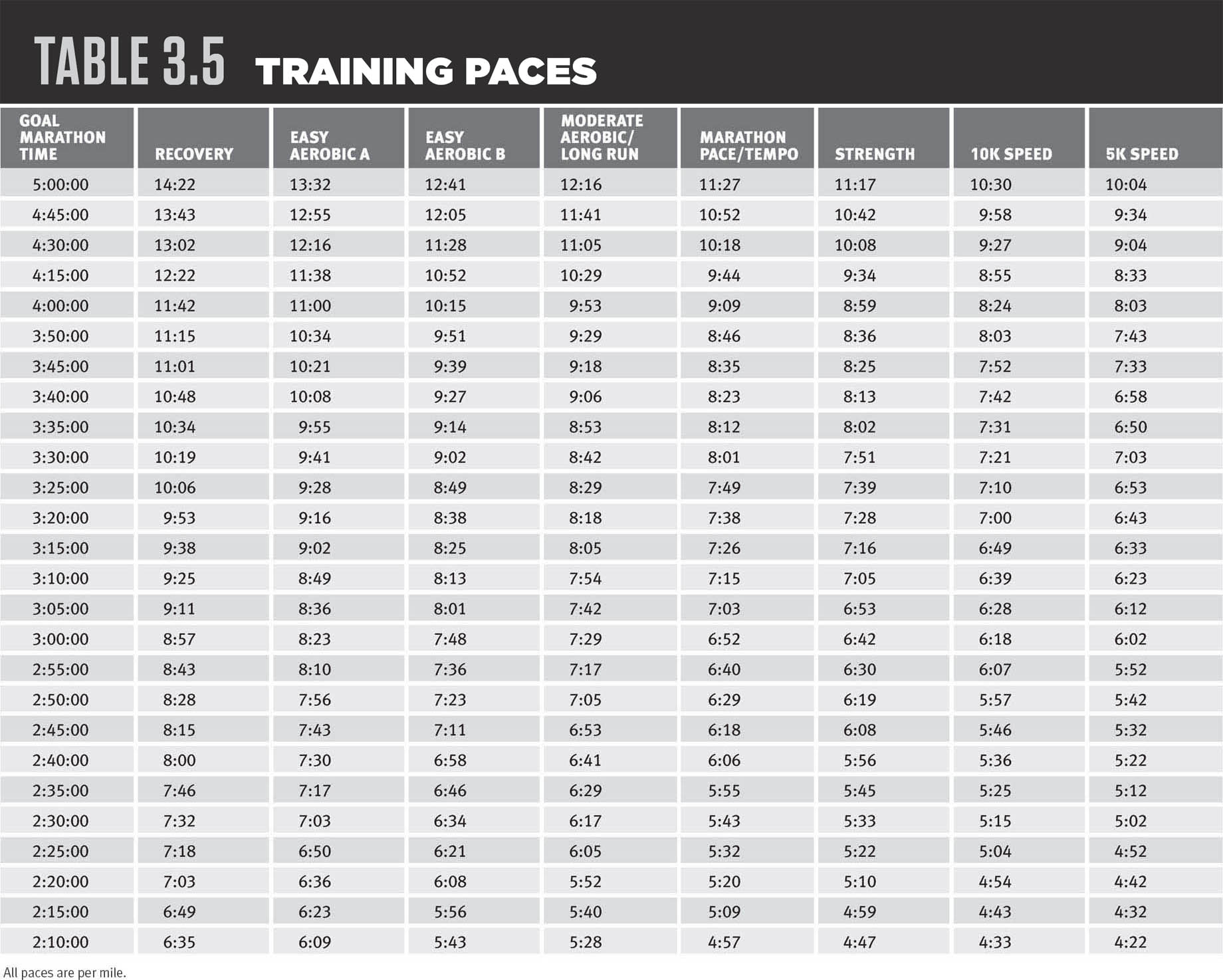

An easy run is usually defined as a run that lasts anywhere between 20 minutes and 2.5 hours at an intensity of 55–75 percent of VO2max. Since most of us don’t have the means to get VO2max tested, the next best thing is to look at pace per mile. The Hansons Marathon Method calls for easy runs to be paced 1–2 minutes slower than goal marathon pace. For example, if your goal marathon pace is 8:00 minutes per mile, then your easy pace should be 9:00–10:00 minutes per mile. While easy running is a necessary part of marathon training, be sure not to run too easy. If your pace is excessively slow, you are simply breaking down tendon and bone without any aerobic benefits. Refer to Table 3.5 for your specific guidelines.

Keep in mind that there is a time for “fast” easy runs (1 minute per mile slower than marathon pace) and “slow” easy runs (2 minutes per mile slower than marathon pace). Warm-ups and cooldowns are two instances when you will want to run on the slower end of the spectrum. Here the idea is to simply bridge the gap between no running and fast running, and vice versa. The day after an SOS workout is another time you may choose a pace on the slow side. For instance, if you have a long run on Sunday and a strength workout on Tuesday, then Monday should be easier to ensure you are recovered and ready to run a good workout on Tuesday. By running the easy runs closer to 2:00 minutes per mile slower than marathon pace, beginning runners will safely make the transition to higher mileage. More advanced runners will likely find that they can handle the faster side of the easy range, even after SOS workouts. The day following a tempo run and the second easy day prior to a long run both provide good chances to run closer to 1 minute per mile slower than marathon race pace.

Whether you are a novice or an experienced runner looking for a new approach, stick to the plan when it comes to easy running. In fact, have fun with the easy days, allowing yourself to take in the scenery or enjoy a social run with friends. Meanwhile, you’ll be simultaneously racking up a laundry list of physiological benefits. What’s more, after a nice, relaxed run, your body will be clamoring for a challenge, ready to tackle the next SOS workout.

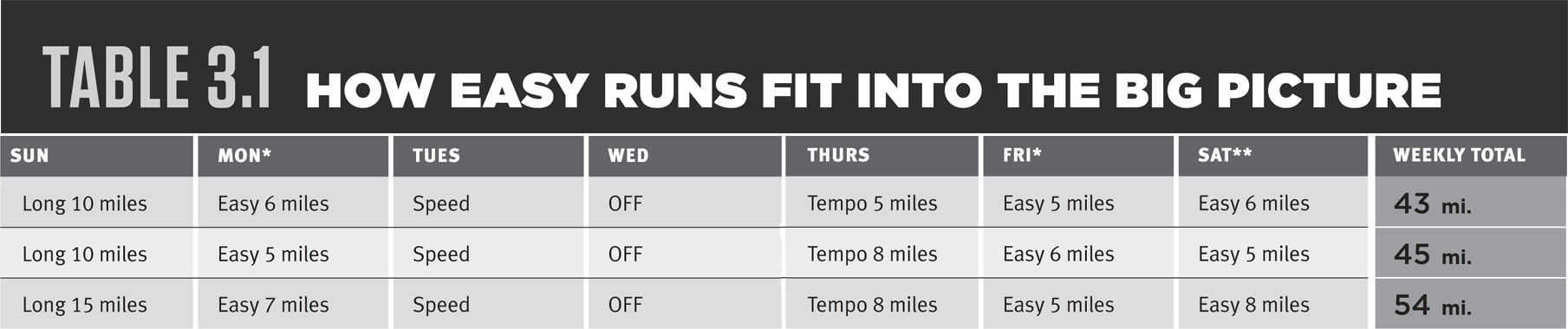

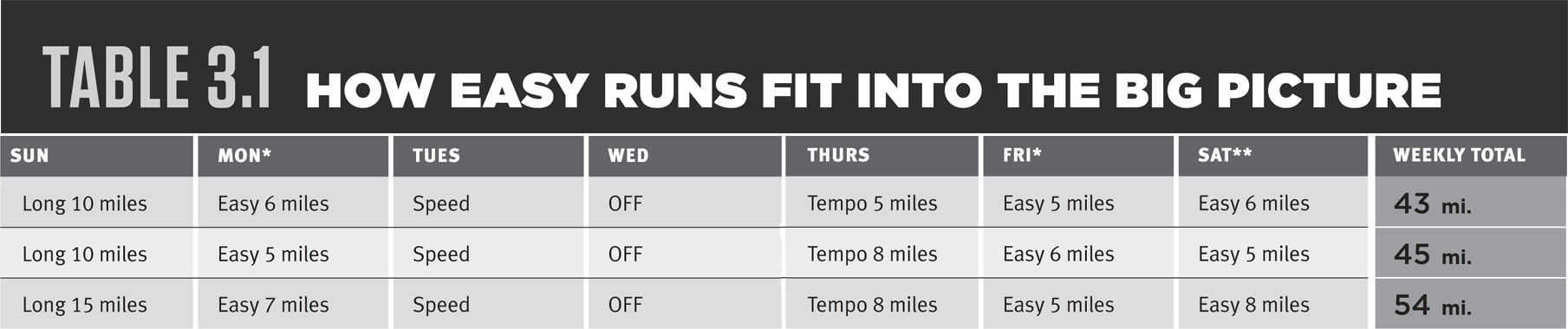

Table 3.1 gives you an idea of how easy runs fit into the overall schedule. This snapshot is taken from weeks 7–9 of the Beginner Program. You’ll notice a variety of things going on throughout each week. On Mondays, you see distances ranging from 5 to 7 miles, followed the next day by a speed session and in front of a longer run on Sunday. Also, look at the easy days that land on Fridays, following the tempo runs on Thursdays. This is where overtraining can occur, because those easy runs are sandwiched between SOS workouts. It is common for this to happen during the first part of the training plans when runners are still feeling pretty fresh, causing them to run faster than prescribed. Remember, these are not the days to worry about how fast you are running; time on your feet is the focus, not pace.

*Monday and Friday pacing should be treated carefully and sensibly.

**Saturday is a day to consider the faster end of your easy pace range.

For the Saturday easy run, you can be a little more flexible with pace. If you feel good, run on the faster end of your easy running spectrum. The metabolic adaptations will happen throughout the pace range, but injury can occur if you make a habit of always running faster, so be sure to moderate your pace. The above sample also shows that you get to a point where it is not logical to keep adding workouts to your training week, and if progression is to take place, then it must come from either adding another easy day (Wednesday) and/or adding mileage to the easy days, not from simply running harder. You will notice in the Hansons Marathon Method training schedules that once the workouts peak in mileage, the easy days are what adds to the weekly mileage.

SOS Workouts

THE LONG RUN

The long run garners more attention than any other component of marathon training. It has become a status symbol among runners in training, a measure by which one compares oneself against one’s running counterparts. It is surprising, then, to discover that much of the existing advice on running long is misguided. After relatively low-mileage weeks, some training plans suggest backbreaking long runs that are more akin to running misadventures than productive training. A 20-mile long run at the end of a three-day-a-week running program can be both demoralizing and physically injurious. The long run has become a big question mark, something you aren’t sure you’ll survive, but you subject yourself to the suffering nonetheless. Despite plenty of anecdotal and academic evidence against such training tactics, advice to reach (or go beyond) the 20-mile long run has persisted. It has become the magic number for marathoners, without consideration for individual differences in abilities and goals. While countless marathoners have made it to the finish line using these programs, the Hansons Marathon Method comes to the table with a different approach (Figure 3.4). Not only will it make training more enjoyable, it will also help you cover 26.2 more efficiently.

FIGURE 3.4 LONG-RUN BENEFITS

While our long-run approach may sound radical, it is deeply rooted in results from inside the lab and outside on the roads. As I read through the exercise-science literature, coached the elite squad with Kevin and Keith, and tested theories in my own training, I realized that revisions to long-held beliefs about marathon training, and in particular long runs, were necessary. As a result, a 16-mile long run is the longest training day for the standard Hansons program. But there’s a hitch: One of Kevin and Keith’s favorite sayings about the long run is, “It’s not like running the first 16 miles of the marathon, but the last 16 miles!” What they mean is that a training plan should simulate the cumulative fatigue that is experienced during a marathon, without completely zapping your legs. Rather than spending the entire week recovering from the previous long run, you should be building a base for the forthcoming long effort.

Take a look at a week in the Advanced Program, which includes a 16-mile Sunday long run (see Table 4.4). Leading up to it, you are to do a tempo run on Thursday and easier short runs on Friday and Saturday. We don’t give you a day completely off before a long run because recovery occurs on the easy running days. Since no single workout has totally diminished your energy stores and left your legs feeling wrecked, you’ll feel the effects of fatigue accumulating over time. The plan allows for partial recovery, but it is designed to keep you from feeling completely fresh going into a long run. Following the Sunday long run, you will have an easy day of running on Monday and a strength workout Tuesday. This may initially appear to be too much, but because your long run’s pace and mileage are tailored to your ability and experience, less recovery is necessary.

The Physiology of Long Runs

Long runs bring with them a laundry list of psychological and physiological benefits, many of which correlate with the profits of easy running. Mentally, long runs help you gradually build confidence as you increase your mileage from one week to the next. They help you develop the coping skills necessary to complete any endurance event. They also teach you how to persist even when you are not feeling 100 percent. Since you never know what is going to happen on marathon day, this can be a real asset. Most notable, however, are the physiological adaptations that occur as a result of long runs. Improved VO2max, increased capillary growth, and a stronger heart are among the benefits. Long runs also help to train your body to utilize fat as fuel on a cellular level. By training your body to run long, you let it adapt and learn to store more glycogen, thereby allowing it to go farther before becoming exhausted.

In addition to improving the energy stores in your muscles, long runs also increase muscle strength. Although your body first exploits the slow-twitch muscle fibers during a long run, it eventually begins to recruit the fast-twitch fibers as the slow-twitch fibers fatigue. The only way to train those fast-twitch fibers is to run long enough to tire the slow-twitch fibers first. By strengthening all of the fibers, you’ll avoid bonking on race day. By now the majority of these adaptations are probably starting to sound familiar. You can expect many of the same benefits reaped from easier work from long runs too.

Long-Run Guidelines

Advice from renowned running researcher and coach Dr. Jack Daniels provides a basis for our long-run philosophy. He instructs runners never to exceed 25–30 percent of their weekly mileage in a long run, whether they are training for a 5K or a marathon. He adds that a 2:30–3:00-hour time limit should be enforced, suggesting that exceeding those guidelines offers no physiological benefit and may lead to overtraining, injuries, and burnout.

Dr. Dave Martin, running researcher at Georgia State University and a consultant to Team USA, goes one step further, recommending that long runs be between 90 minutes and 2 hours long. While he proposes 18–25-mile long runs for high-level marathoners, one must take into consideration that a runner of this caliber can finish a 25-mile run in under 3:00 hours. This highlights the importance of accounting for a runner’s long-run pace. Dr. Joe Vigil, a Team USA coach and scientist, further supports this notion, advising that long runs be increased gradually until the athlete hits 2:00–3:00 hours. Certainly a 25-mile run completed in less than 3:00 hours by an elite runner will provide different physiological adaptations than a 25-mile run that takes a less experienced runner 3:30 hours or more.

According to legendary South African researcher and author, Dr. Tim Noakes, a continual, easy-to-moderate run at 70–85 percent VO2max that is sustained for 2:00 hours or more will lead to the greatest glycogen depletion. Exercise physiologist Dr. David Costill has also noted that a 2:00-hour bout of running reduces muscle glycogen by as much as 50 percent. While this rate of glycogen depletion is acceptable on race day, it is counterproductive in the middle of a training cycle, as it takes as many as 72 hours to bounce back. When you diminish those energy stores, you can end up benched by fatigue, missing out on important training, or training on tired legs and potentially hurting yourself. Instead of risking diminishing returns and prescribing an arbitrary 20-mile run, the Hansons Marathon Method looks at percentage of mileage and total time spent running. While 16 miles is often the suggested maximum run, we are more concerned with determining your long run based on your weekly total mileage and your pace for that long run. It may sound unconventional, but you’ll find that nothing we suggest is random; it is all firmly based in science with proven results.

Long-Run Mileage: Training to Adapt or Training to Survive?

Recreational marathoners are often told to do 20-plus-mile long runs as a way to prepare themselves mentally. And while I understand that argument, I doubt that it’s worth the possible consequences. In 1985, researchers studied 40 trained males who had just completed a marathon. All had muscular damage in their legs, which was not surprising. What was surprising, however, was the damage to mitochondria and capillaries. After a week, glycogen levels were back to normal, but the damage remained. After eight weeks, there was still evidence of damage. If you are doing several 20-mile runs in preparation, then you are likely doing similar damage to your legs. Mitochondria and capillaries are crucial for performance. If we continually do damage to these components, then are we boosting adaptations or are we simply taking away what we spent the past months building? If we continually take away from this supply, then we end up merely surviving from long run to long run, not to mention greatly increasing our chance for injury. By backing down a little, we get the physiological benefits, and we are training to adapt, not just to survive.

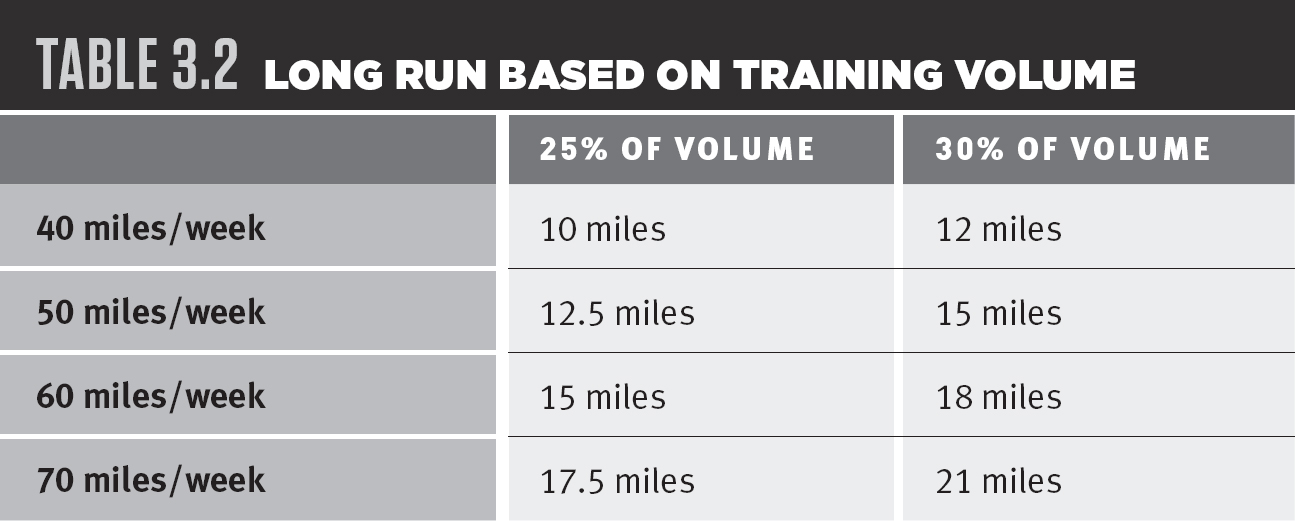

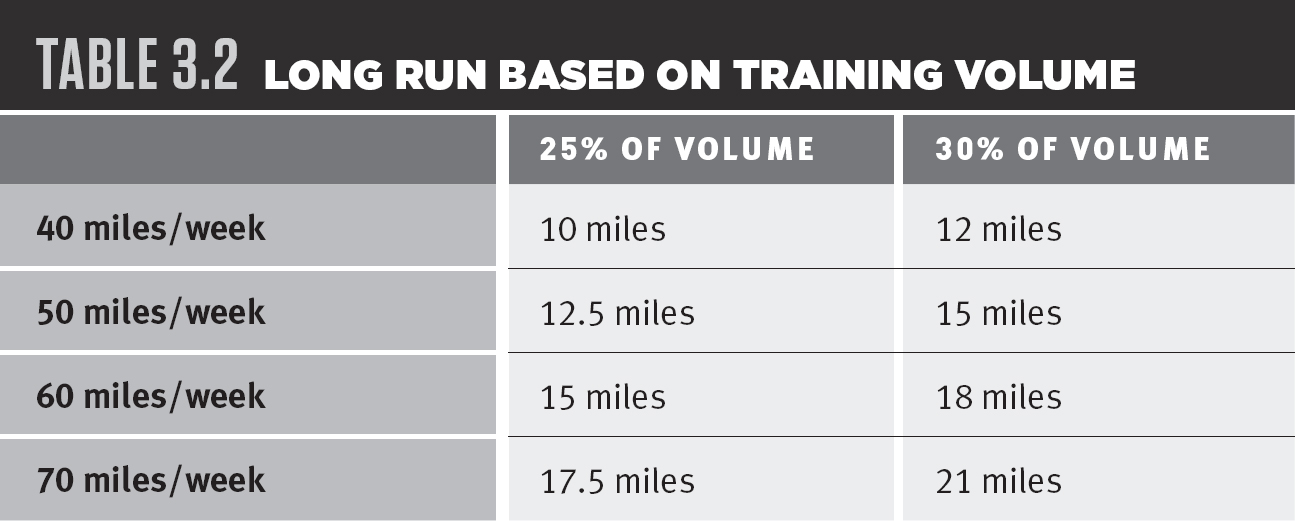

As stipulated by Dr. Noakes, it is widely accepted among coaches that long runs shouldn’t exceed 25–30 percent of weekly mileage. Even so, that guideline manages to get lost in many marathon-training programs in the effort to cram in mileage. For instance, a beginning program that peaks at 40–50 miles per week and recommends a 20-mile long run is violating the cardinal rule. Although the epic journey is usually sandwiched between an easy day and a rest day, there is no getting around the fact that it accounts for around 50 percent of the runner’s weekly mileage. Looking at Table 3.2, you can see how far your long run should be based on your total mileage for the week.

The numbers illustrate that marathon training is a significant undertaking and should not be approached with randomness or bravado. They also make apparent the fact that many training programs miss the mark on the long run. If you are a beginning or low-mileage runner, your long runs must be adjusted accordingly. What is right for an 80-mile-a-week runner is not right for one who puts in 40 miles a week.

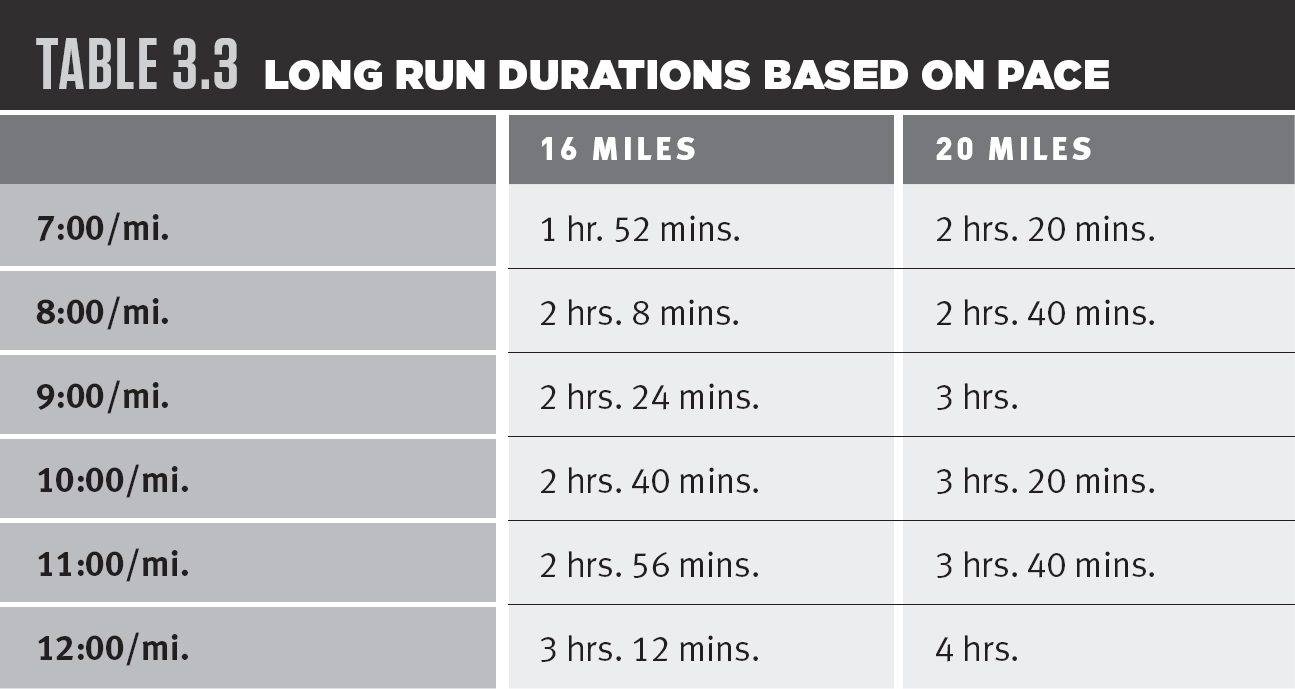

In addition to running the optimal number of miles on each long run, you must also adhere to a certain pace to get the most benefit. Since we don’t all cover the same distance in the same amount of time, it makes sense to adjust a long run depending on how fast you’ll be traveling. The research tells us that 2:00–3:00 hours is the optimal window for development in terms of long runs. Beyond that, muscle breakdown begins to occur. Look at Table 3.3 to see how long it takes to complete the 16- and 20-mile distances based on pace.

The table demonstrates that a runner covering 16 miles at a 7:00-minute pace will finish in just under 2:00 hours, while a runner traveling at an 11:00-minute pace will take nearly 3:00 hours to finish that same distance. It then becomes clear that anyone planning on running slower than a 9:00-minute pace should avoid the 20-mile trek. This is where the number 16 comes into play. Based on the mileage from the Hansons marathon programs, the 16-mile long run fits the bill on both percentage of weekly mileage and long-run total time.

ASK THE COACH

At what pace should I do my long run?

We generally coach runners to hold an easy-to-moderate pace throughout a long run. Instead of viewing your long run as a high-volume easy day, think of it as a long workout. If you are new to marathoning, err on the easy side of pacing as you become accustomed to the longer distances. More advanced runners should maintain a moderate pace as their muscles have adapted to the stress of such feats of endurance. Refer to the pace chart for exact paces. In the long run (literally and figuratively), when you avoid overdoing these lengthy workouts, you reap more benefits and avoid the potential downfalls of overtraining.

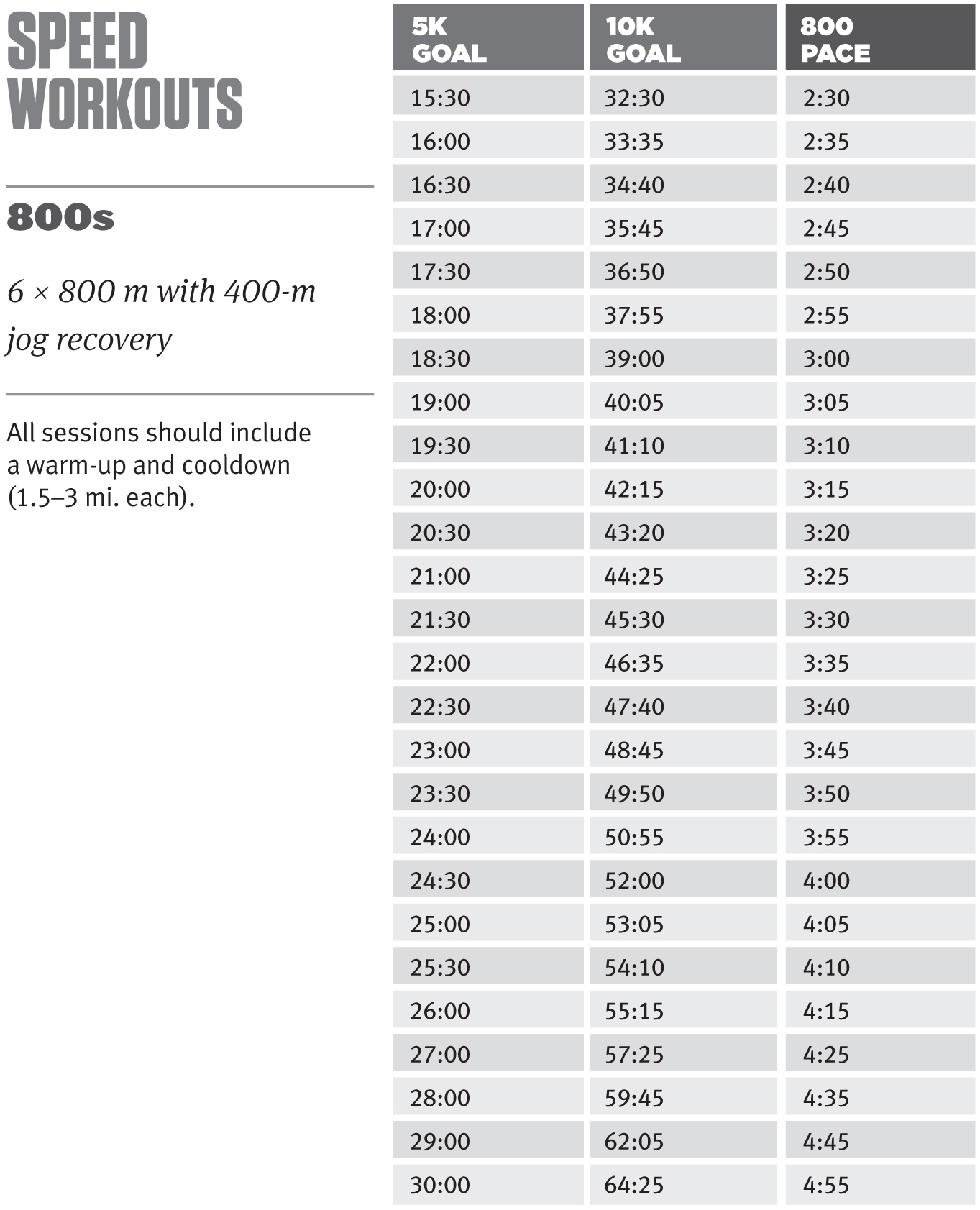

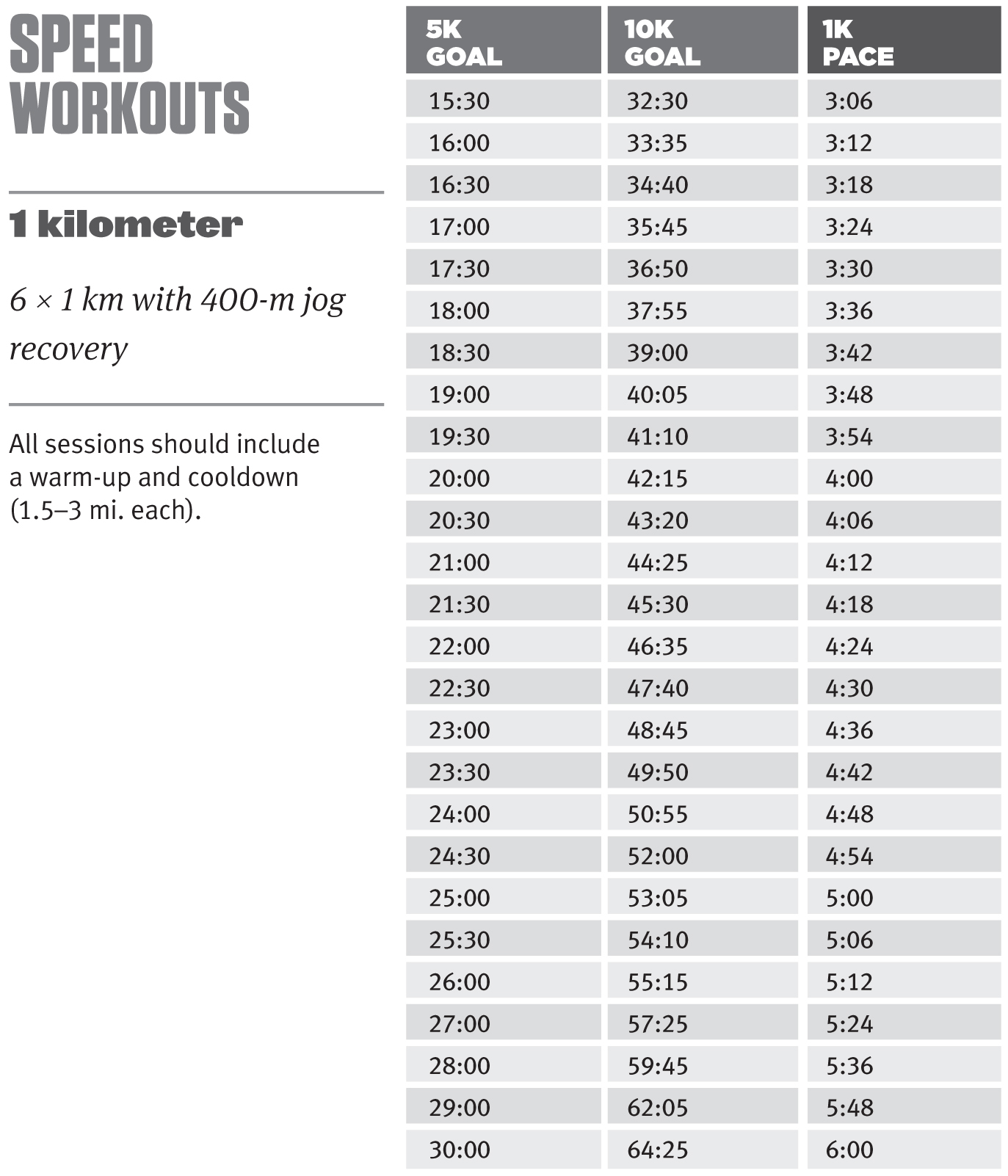

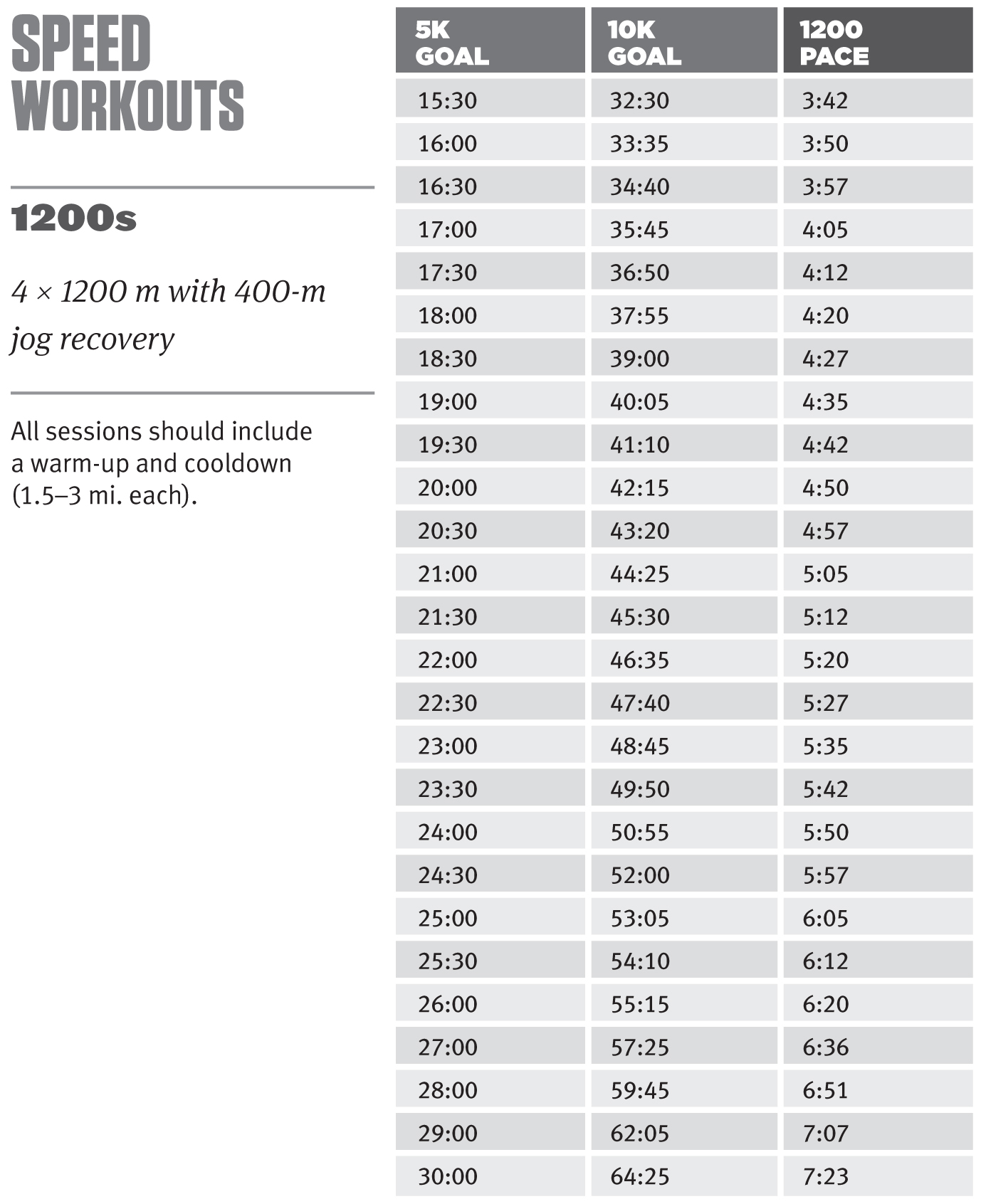

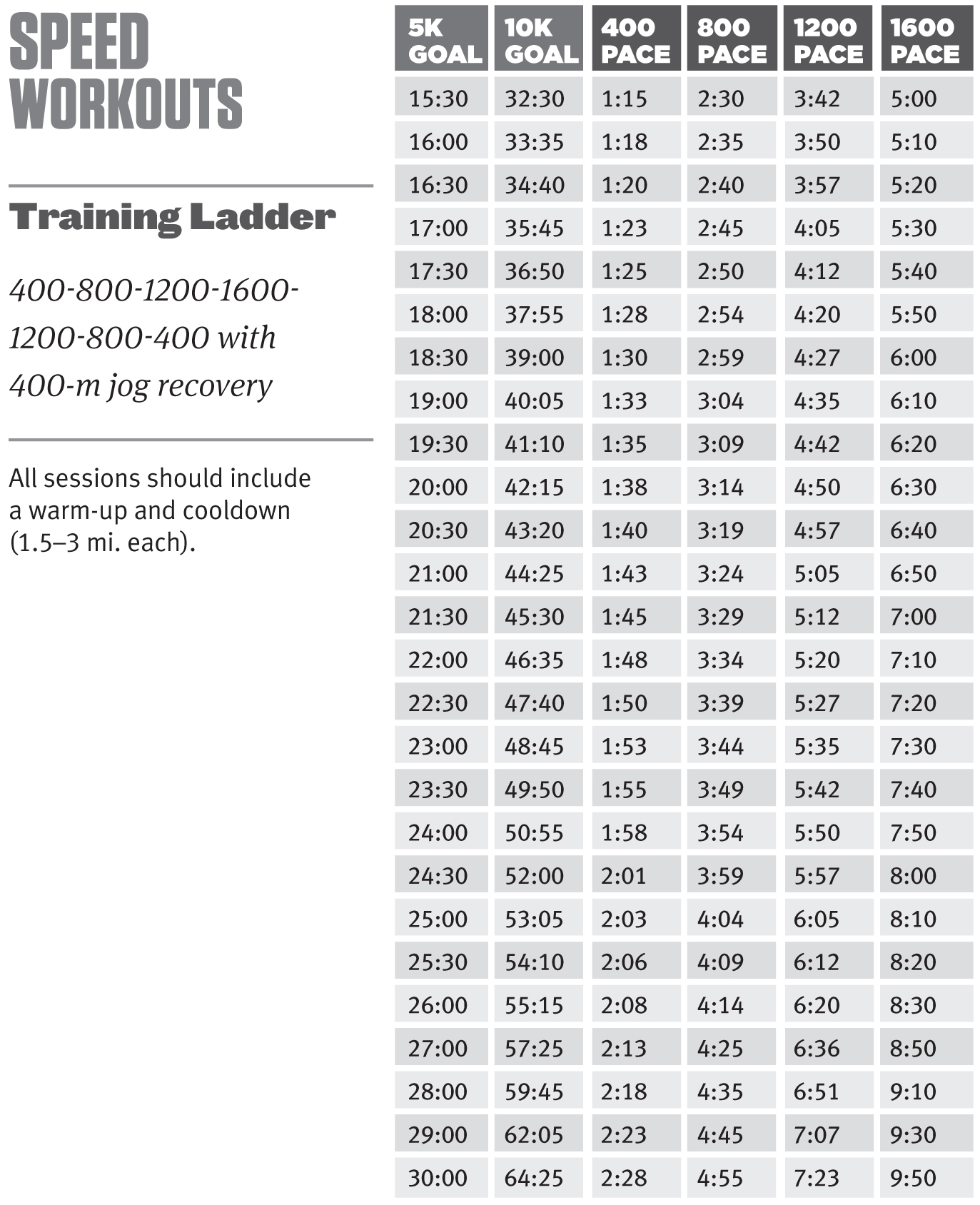

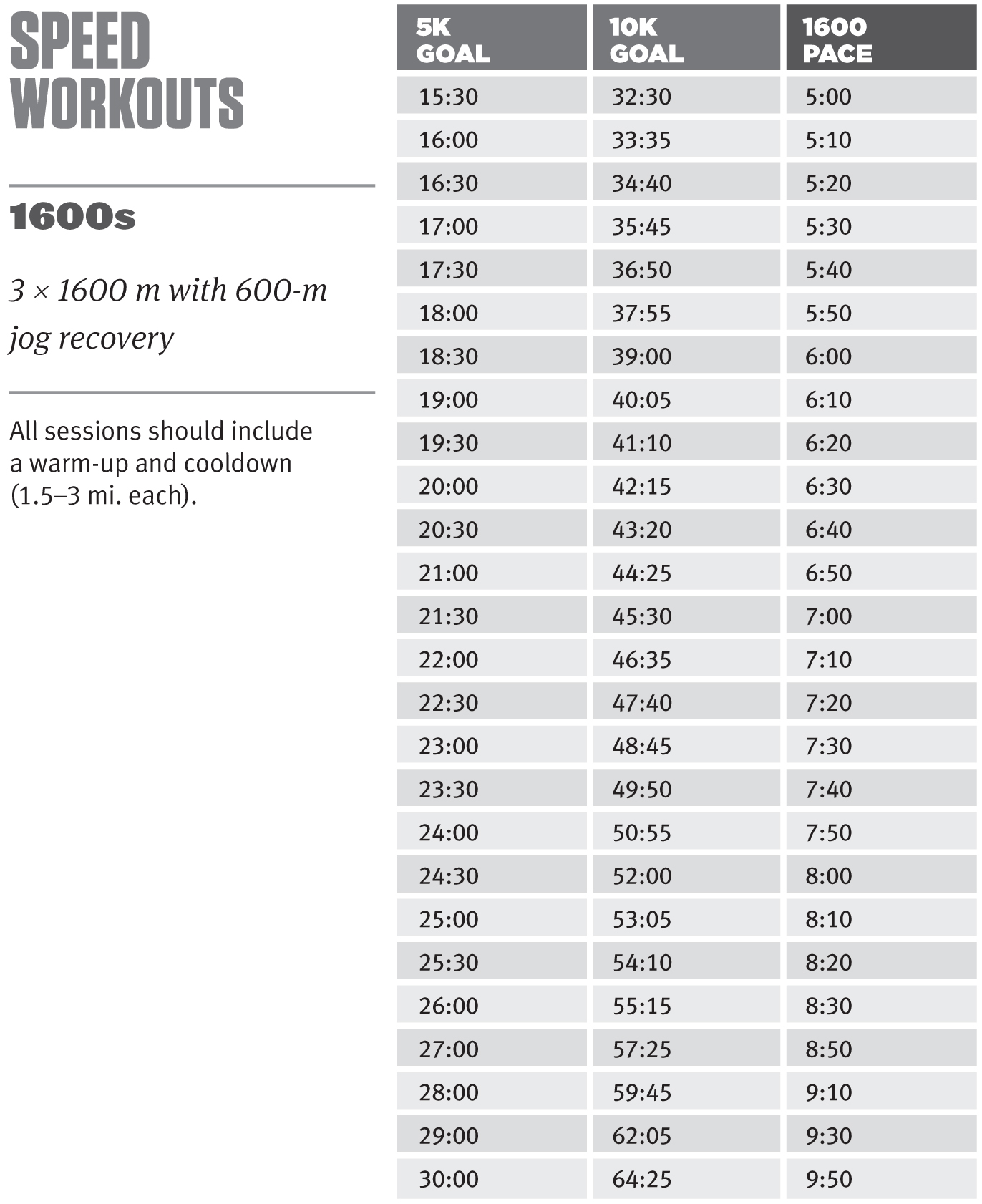

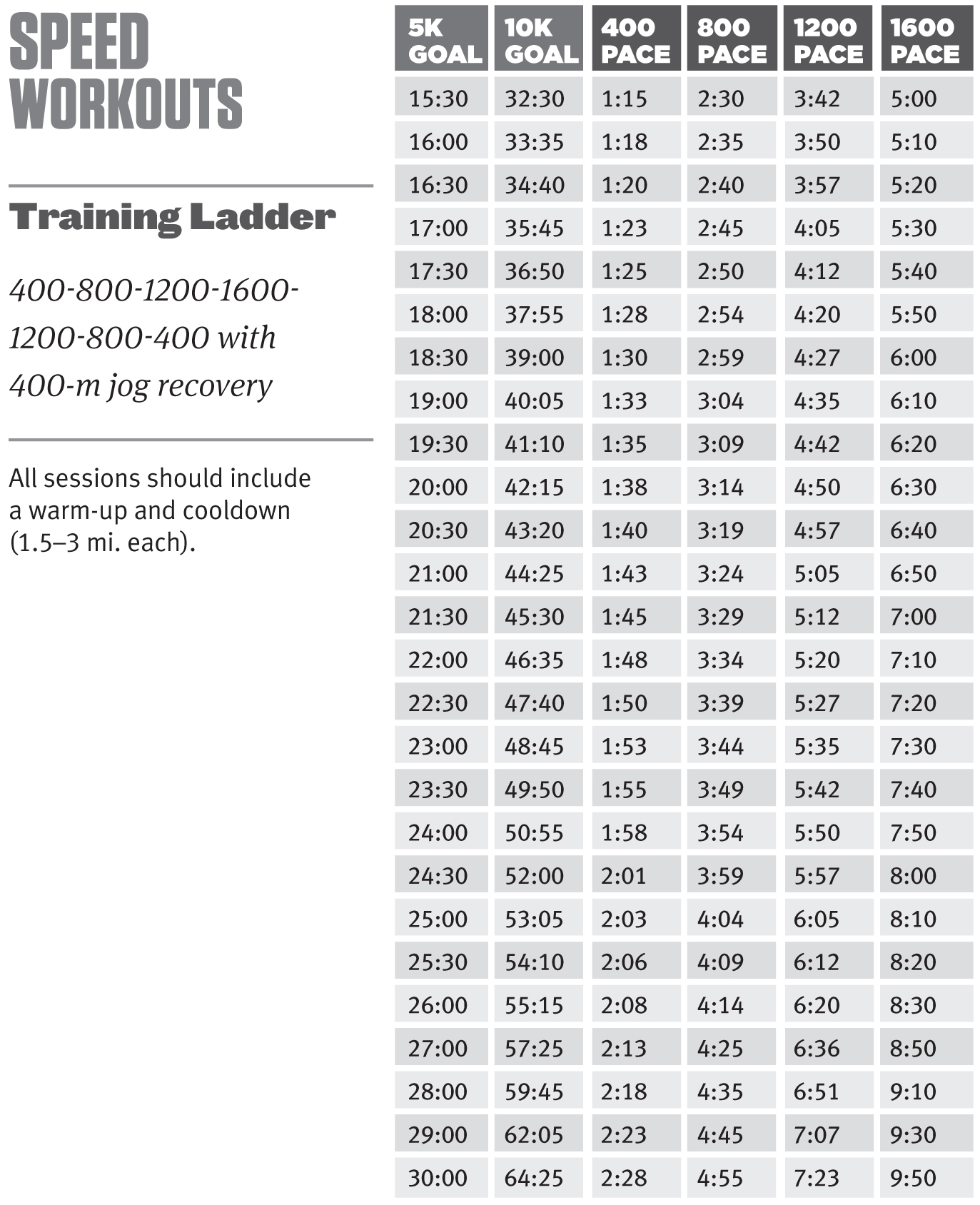

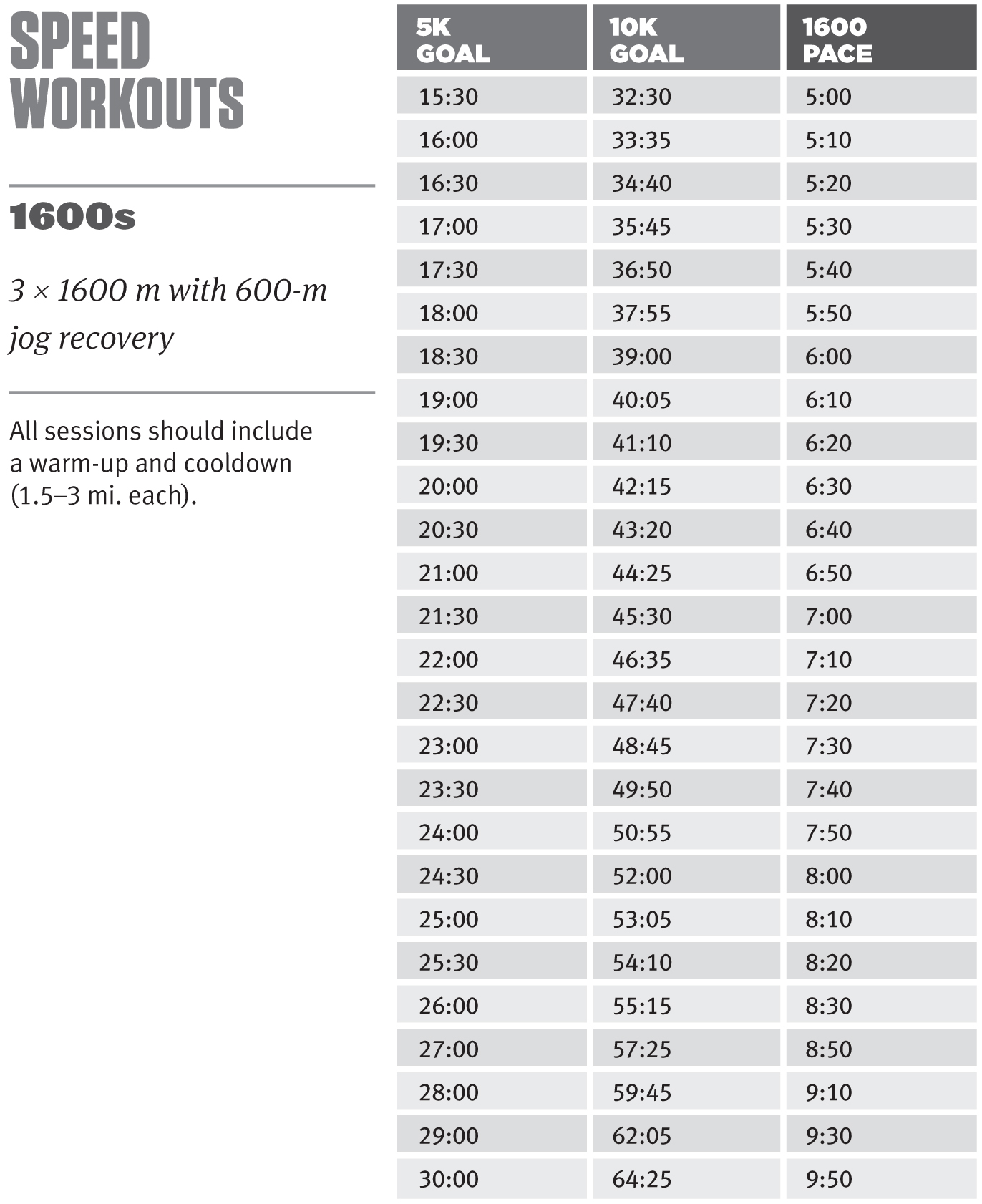

SPEED WORKOUTS

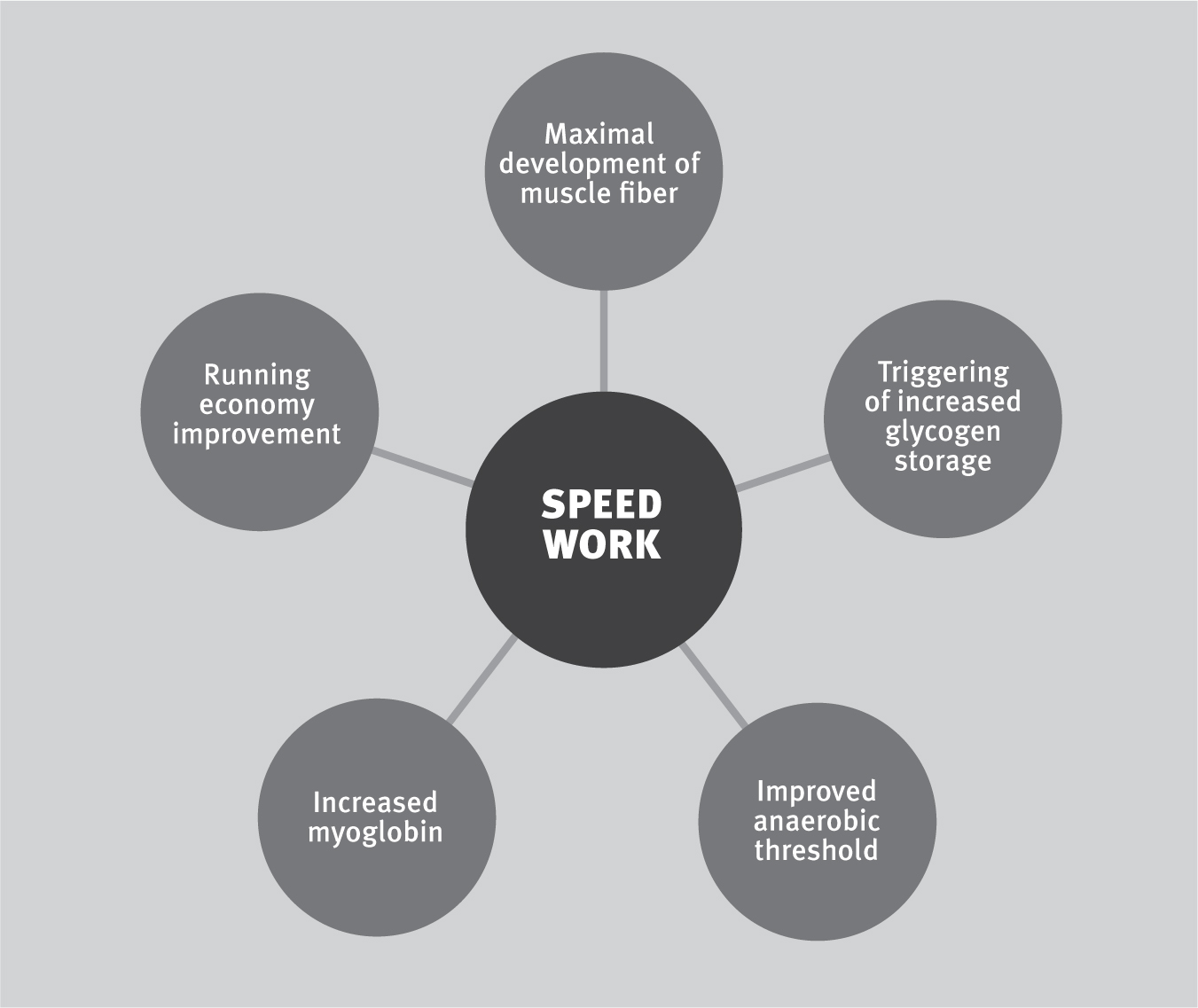

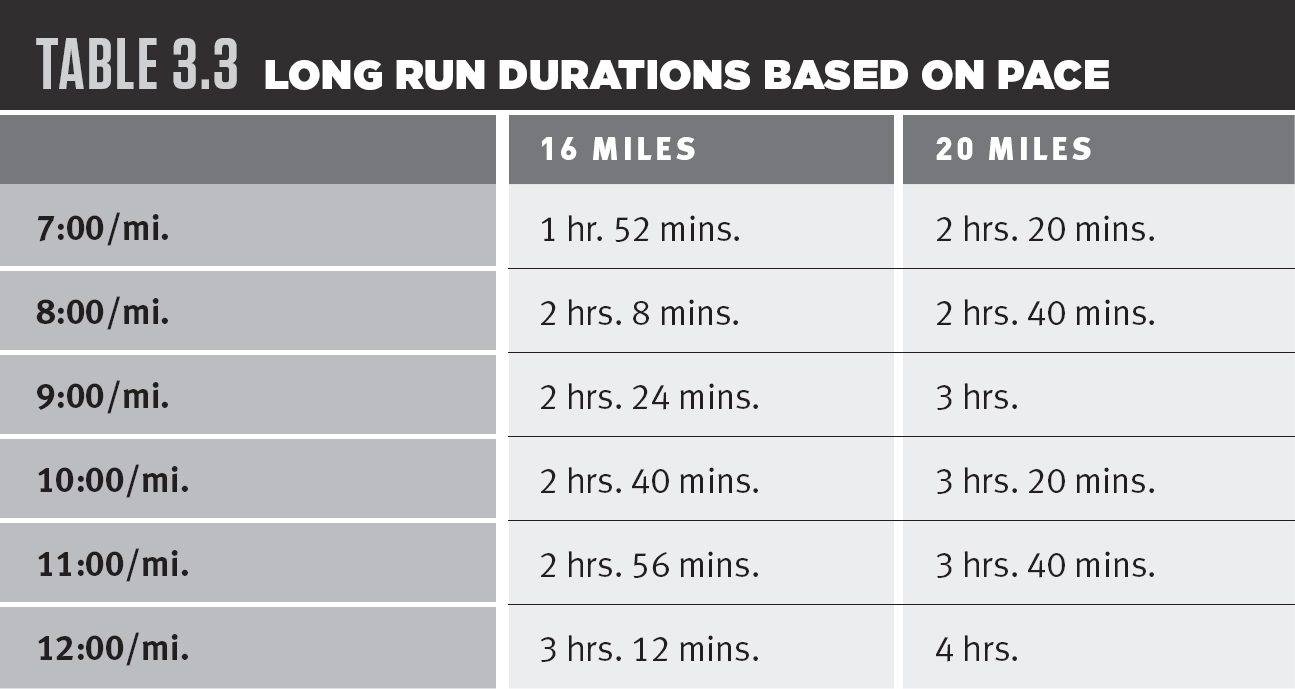

With speed workouts, marathon training begins to get more interesting. When we refer to speed training, we are talking about interval sessions, also called repeat workouts. Speed workouts require you to run multiple bouts of certain distances at high intensities with recovery between each. Not only does this type of training play a role in prompting some of the important physiological changes we already discussed, it also teaches your mind to handle harder work. While easy days are typically low pressure, speed workouts require you to put your game face on and come ready to push hard. Discipline is one of many benefits (see Figure 3.5). While you may be able to complete an easy run the morning following a late night out on the town, if you want to get the most out of your speed work you’re going to need to eat a hearty dinner and hit the hay at a decent hour. Whatever you give up to execute these workouts, optimally, the training will give back to you tenfold. Every speed workout you complete is like money in the bank when it comes to resources on which you can draw during the most difficult moments of the marathon.

FIGURE 3.5 SPEED WORK BENEFITS

Some marathoners have done little or no speed workouts in the form of repeats or intervals. If you are new to marathoning and your past speed workouts have consisted of simply running some days slightly faster than others, you are in the majority. Luckily, the speed workouts in our plans provide an introductory course on how to implement harder workouts, no matter what distance for which you are training. As you learn how to properly implement speed workouts, your training will be transformed from a somewhat aimless approach to fitness to a guided plan of attack. Speed workouts can also help you predict what you are capable of in the marathon. By implementing speed work, you can successfully race a shorter race, such as a 5K or 10K, and then plug that time into a race equivalency chart to determine your potential marathon time. (See Table 6.1.) Additionally, this can help to highlight weak areas so you can address them early on.

Surprisingly, advanced runners sometimes make the same mistakes that novices do in terms of speed training; namely, they neglect it. For instance, we have had runners come to us feeling stale after running two to three marathons in a year. Along with a flat workout tends to come stagnated finishing times. Digging into these runners’ histories, we often find that they are running so many marathons that they have completely forgone speed training, spending all their time on long runs, tempo runs, and recovery. That’s where we set them straight by guiding them through the Hansons Marathon Method. As with the other types of workouts, speed training is an important part of constantly keeping your system on its toes, requiring it to adapt to changing workouts that vary in intensity and distance.

Physiology of Speed Workouts

The greatest beneficiaries of speed training are the working muscles. With speed sessions, not only do the slow-twitch fibers become maximally activated to provide aerobic energy, so too do the intermediate fibers. This forces the slow-twitch fibers to maximize their aerobic capacities, but when they fatigue, it also trains the intermediate fibers to step in. As a result of better muscle coordination, running economy also improves. Stimulated by everything from speed workouts to easy running, running economy is all about how efficiently your body utilizes oxygen at a certain pace. Remember, running economy is a better predictor of race performance than VO2max, so improvements can have a great influence on marathon performance.

Another adaptation that occurs through speed work is the increased production of myoglobin. In fact, research tells us that the best way to develop myoglobin is through higher intensity running (above 80 percent VO2max). Similar to the way hemoglobin carries oxygen to the blood, myoglobin helps transport oxygen to the muscles and then to the mitochondria. With its help, the increased demand for oxygen is met to match capillary delivery and the needs of the mitochondria.

Exercise at higher intensities can also increase anaerobic threshold. In short, the speed intervals provide a two-for-one ticket by developing the anaerobic threshold and VO2max during the same workout. Finally, since speed sessions include high-intensity running near 100 percent VO2max (but not over), glycogen stores are rapidly depleted. In fact, during these workouts glycogen is providing upward of 90 percent of the energy. This, in turn, forces the muscles to adapt and store more glycogen to be used later in workouts.

Speed Guidelines

You’ll notice that the speed segments of our training plans are located toward the beginning of the training block, while later portions are devoted to more marathon-specific workouts. When you consider our contentions about building fitness from the bottom up, this may seem counterintuitive. However, if speed workouts are executed at the right speeds, it makes sense to include them closer to the beginning of your training cycle. As in other workouts, correct pacing is essential. When many coaches discuss speed training, they are referring to work that is done at 100 percent VO2max. In reality, when you run at 100 percent VO2max pace, it can only be maintained for 3–8 minutes. If you are a beginner, 3 minutes is likely more realistic, while an elite miler may be able to continue for close to 8 minutes. Running your speed workouts at or above 100 percent VO2max causes the structural muscles to begin to break down and forces your system to rely largely on anaerobic sources. Not only does this overstress the anaerobic system, it doesn’t allow for the positive aerobic adaptations you need to run a good marathon. Our marathon programs base speed work on 5K and 10K goal times and these races both last much longer than 3–8 minutes. Rather than being at 100 percent VO2max, you’re probably between 80 and 95 percent VO2max when running these distances. At these intensities, you aren’t running fast enough to create an onset of severe acidosis (a condition when the muscles have a low pH brought on by high levels of blood lactate). Unlike other plans, we instruct you to complete speed workouts at slightly less than 100 percent VO2max pace to spur maximum physiological adaptations. If you go faster, gains are nullified and injuries probable.

ASK THE COACH

Why is speed positioned early in the program?

Your most race-specific work should be done close to the race. For that reason, if you are preparing for a 5K, then yes, speed should be closer to your race. But in the case of marathon preparation, there is little purpose in doing fast repeats on a track to prepare for the feeling of being at 22 miles with more than 4 to go.

Also, putting speed work early in the program allows a runner to do some shorter races before transitioning into full-blown marathon-training mode. The speed is relative to the distance being raced. I typically prescribe 10K pace, which would be slower than in a traditional 5K or 10K training schedule. That said, at this pace, it is not as strenuous as speed work would be for an all-out assault on a 5K PR.

In addition to pace, duration of the speed intervals is important. Optimal duration lies between 2 and 8 minutes. If the duration is too short, the amount of time spent at optimal intensity is minimized and precious workout time wasted. However, if the duration is too long, lactic acid builds up and you are too tired to complete the workout at the desired pace. As a result, the duration of speed intervals should be adjusted to your ability and experience levels. For example, a 400-meter repeat workout, with each interval lasting around 2 minutes, may be the perfect fit for a beginner. Conversely, the same workout may take an advanced runner 25 percent less time to complete each 400-meter repeat, therefore resulting in fewer benefits.

ASK THE COACH

Should I adjust my speed workouts to stay within the optimal 2–8-minute range?

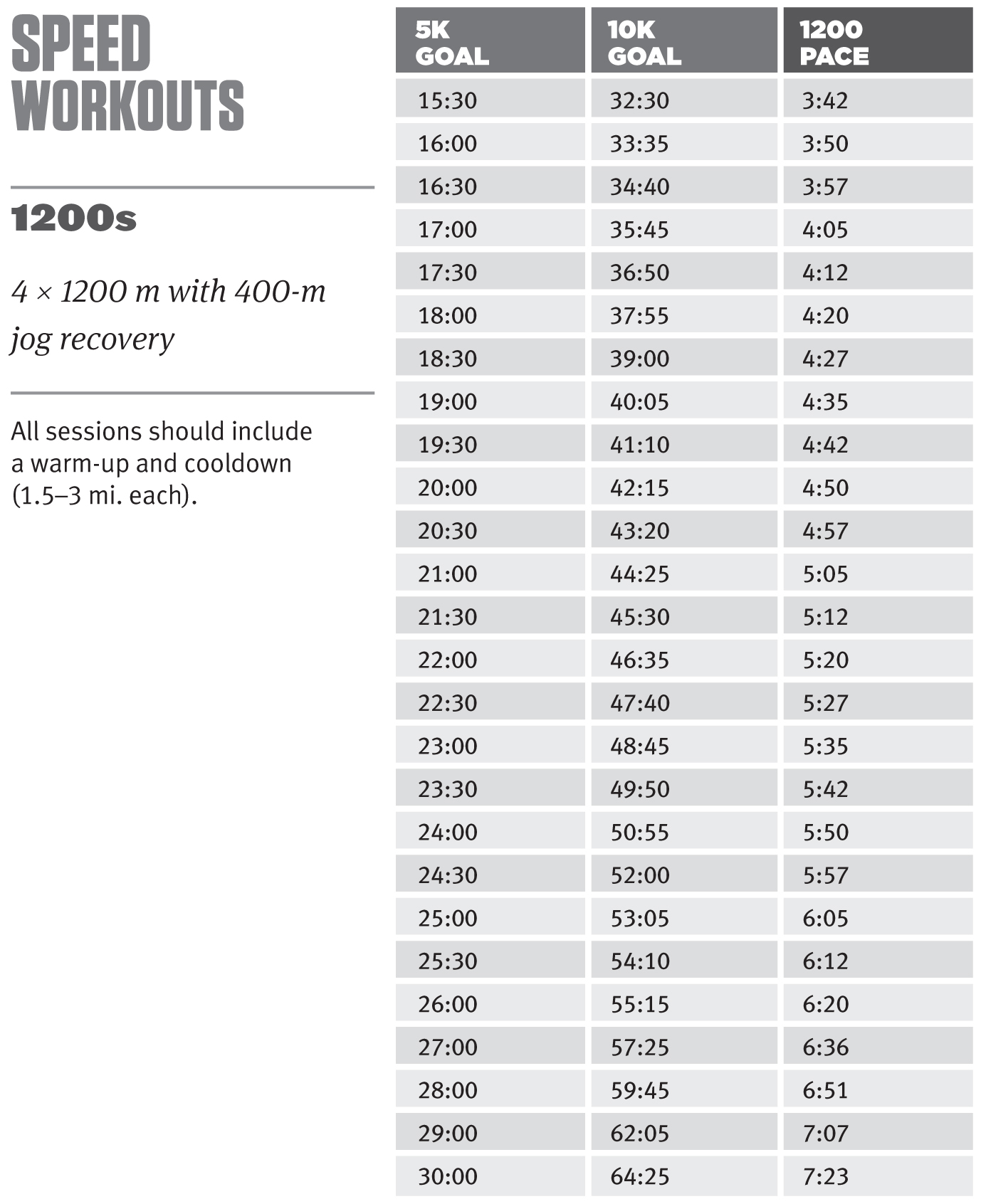

Probably not. For those using the Beginner Program, the repeats from 400 meters to 1 kilometer should not present an issue. The line becomes blurred for the 1200-meter and 1600-meter repeats. Here you may be conflating a speed workout with a strength workout. However, that’s OK because it will help you transition from the speed workouts and the upcoming strength workouts. If, on the other hand, you are using the Advanced Program, then time will likely not be an issue because you’ll probably be running the workouts under that 8-minute-per-repeat ceiling.

Recovery is another important part of speed sessions, allowing you the rest you need to complete another interval. Guidelines for recovery generally state that rest should be between 50 and 100 percent of the repeat duration time. For instance, if the repeat is 2 minutes in duration, the recovery should be between 1 and 2 minutes. However, we tend to give beginners longer recovery time at the beginning of the speed sessions to sustain them through the entire workout. With further training, recovery time is shortened as an athlete is able to handle more work. When it comes to recovery, Kevin and Keith always say: “If you are too tired to jog the recovery interval, then you’re running too hard!” It’s a good rule of thumb. The session is designed to focus on accumulating time within the desired intensity range. If you run your repeats so hard that you aren’t able to jog during your recovery time, you are unlikely to be able to run the next interval at the desired pace. In the end, these speed sessions should total 3 miles of running at that faster intensity, in addition to the warm-up, cooldown, and recovery periods. If you can’t get through the intervals to hit 3 miles total, you’re running too hard for your abilities and thereby missing out on developing the specific adaptations discussed.

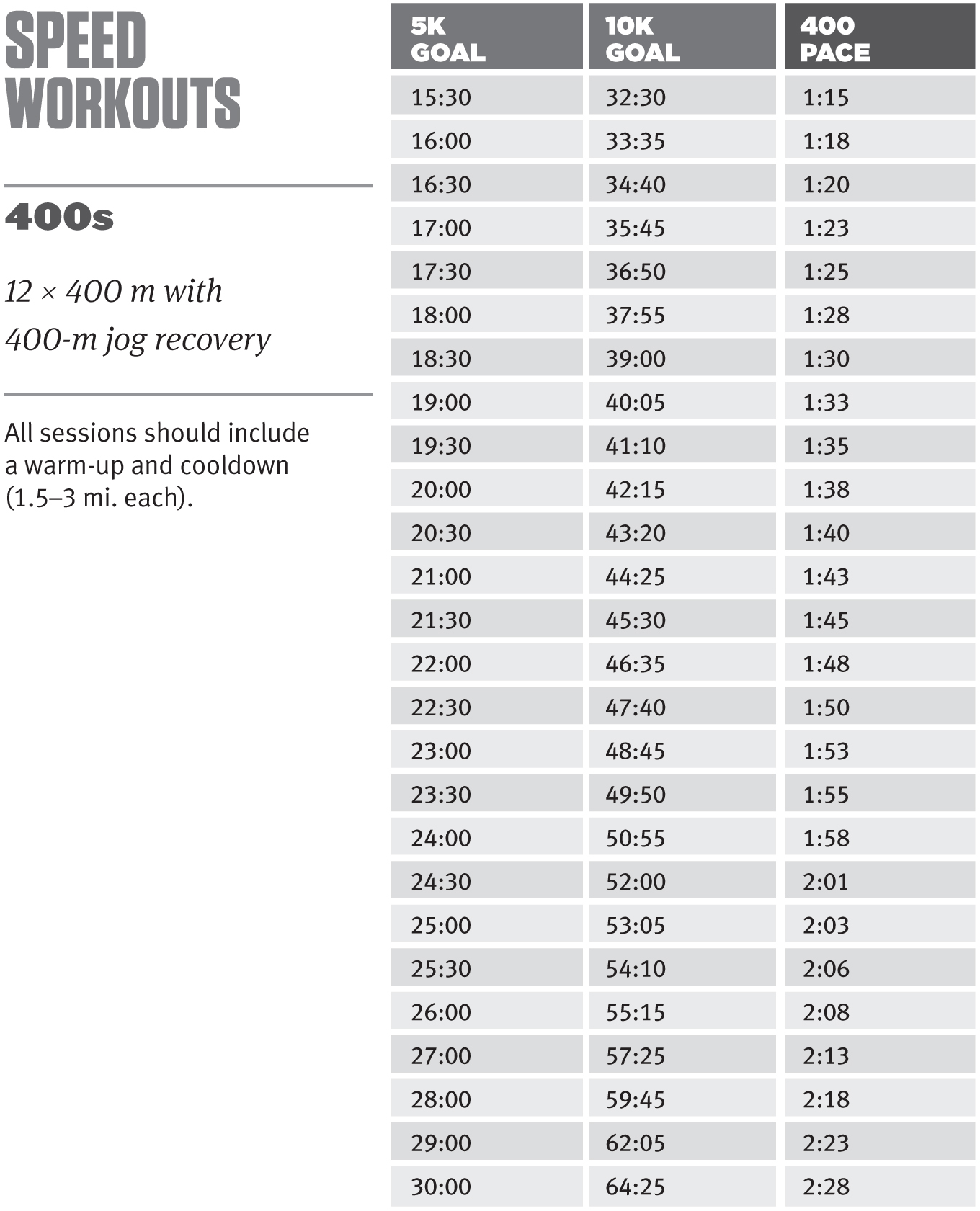

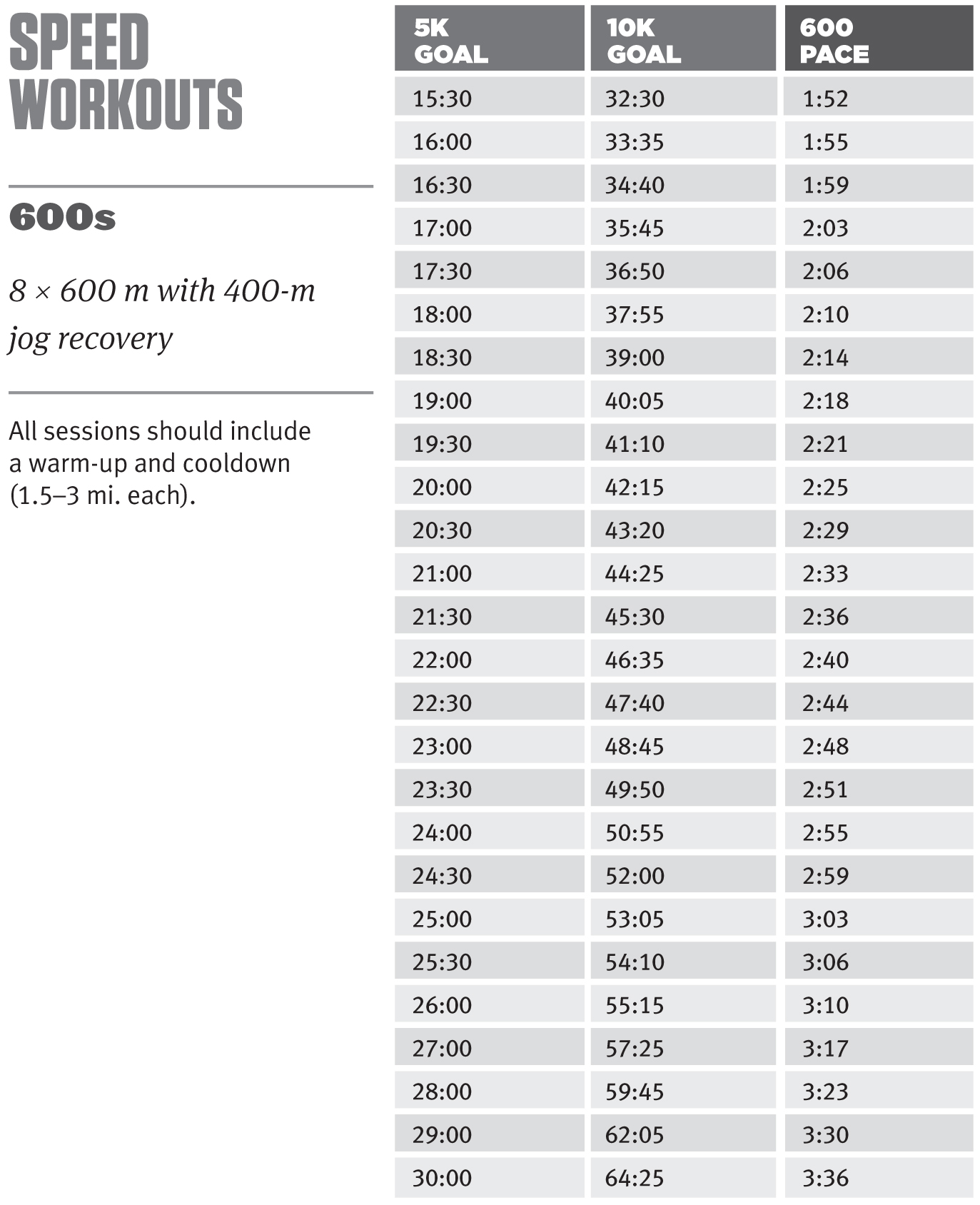

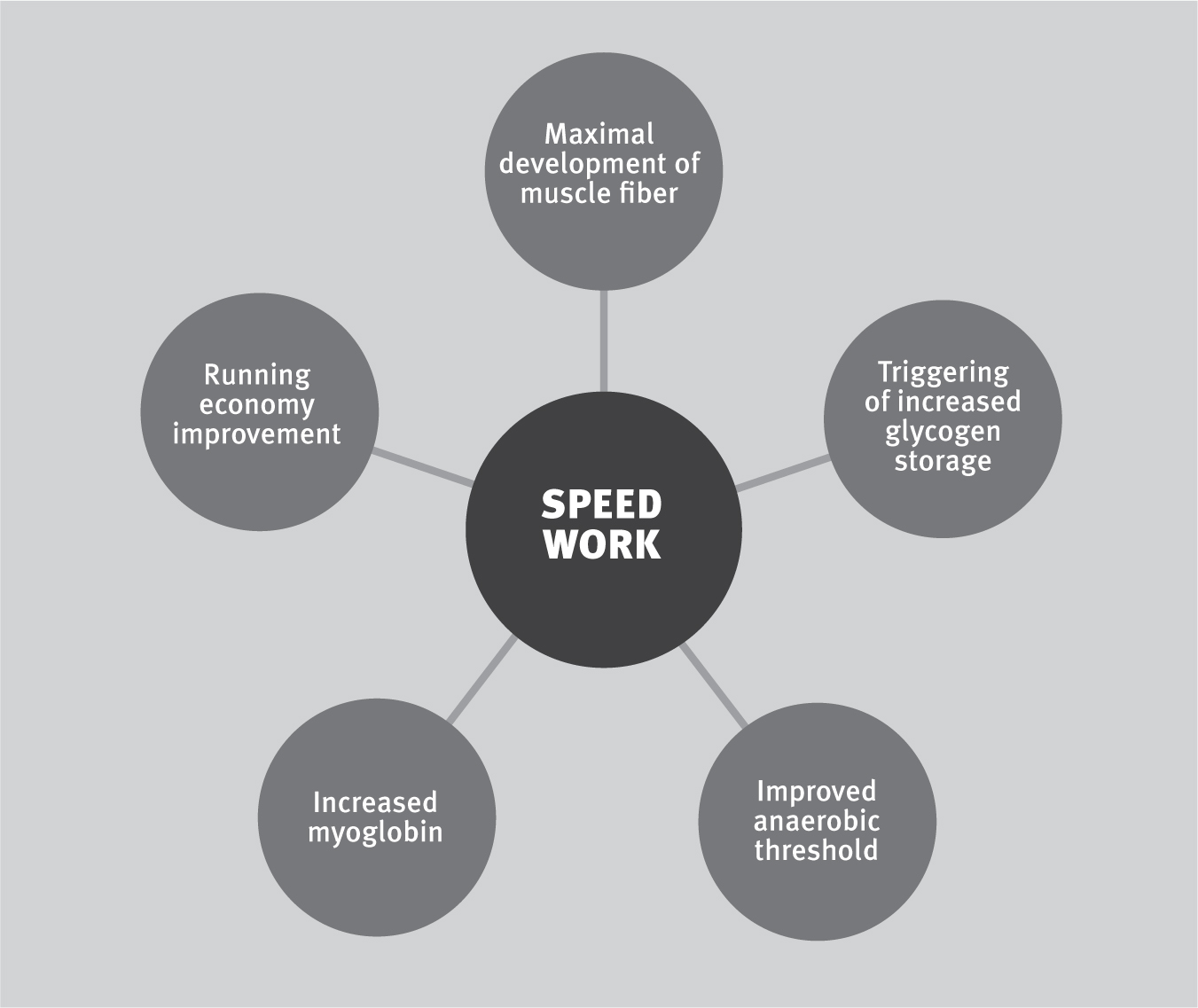

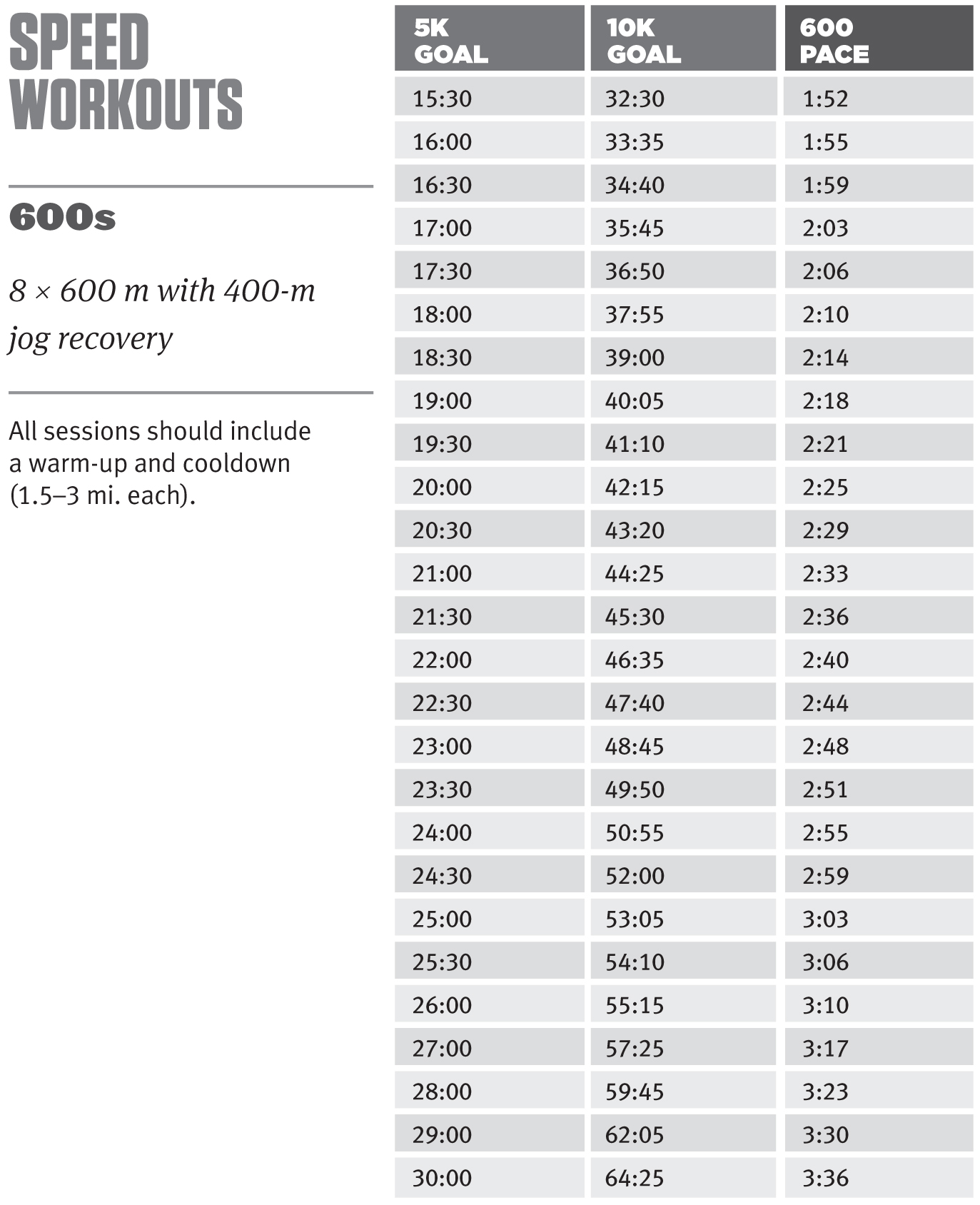

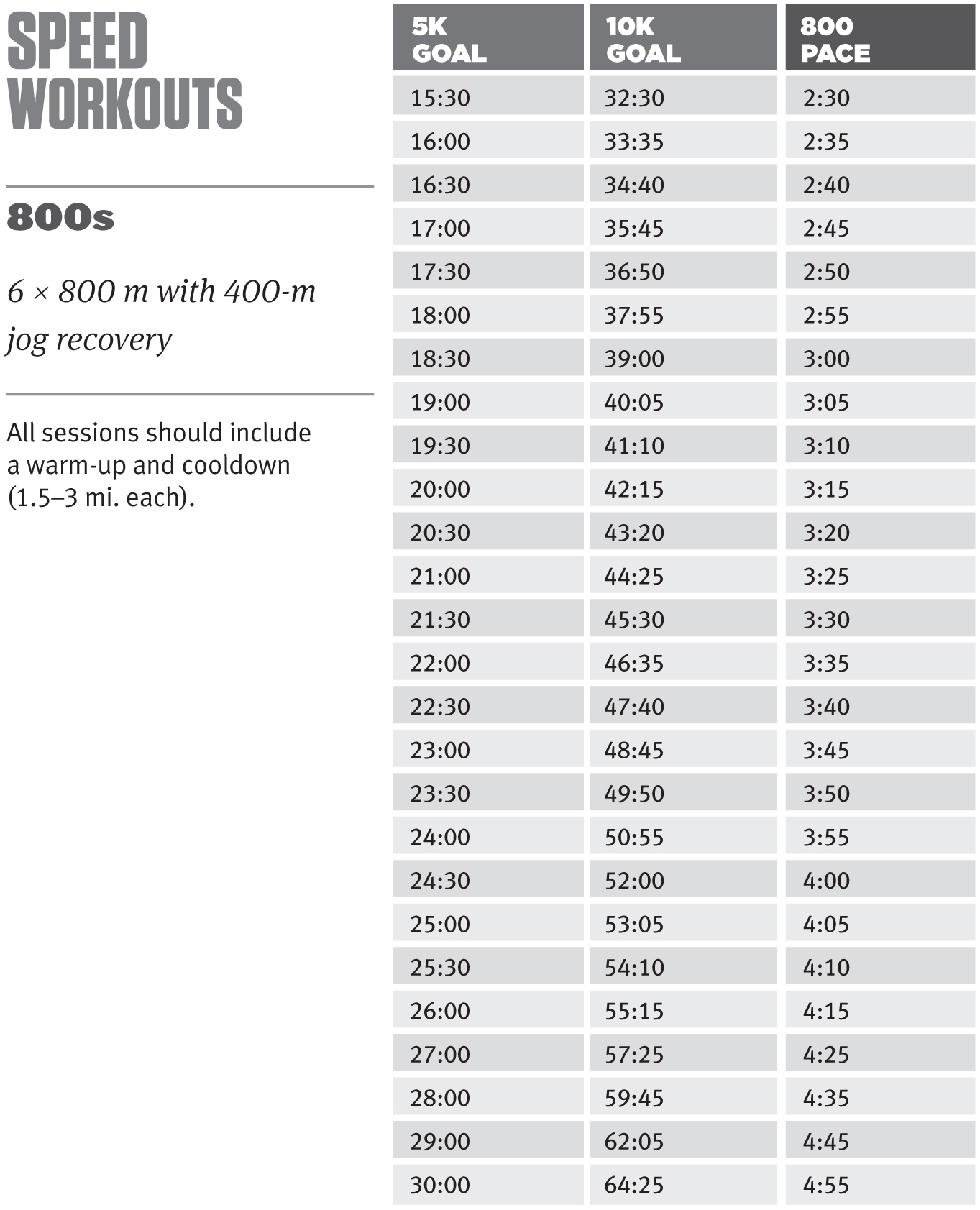

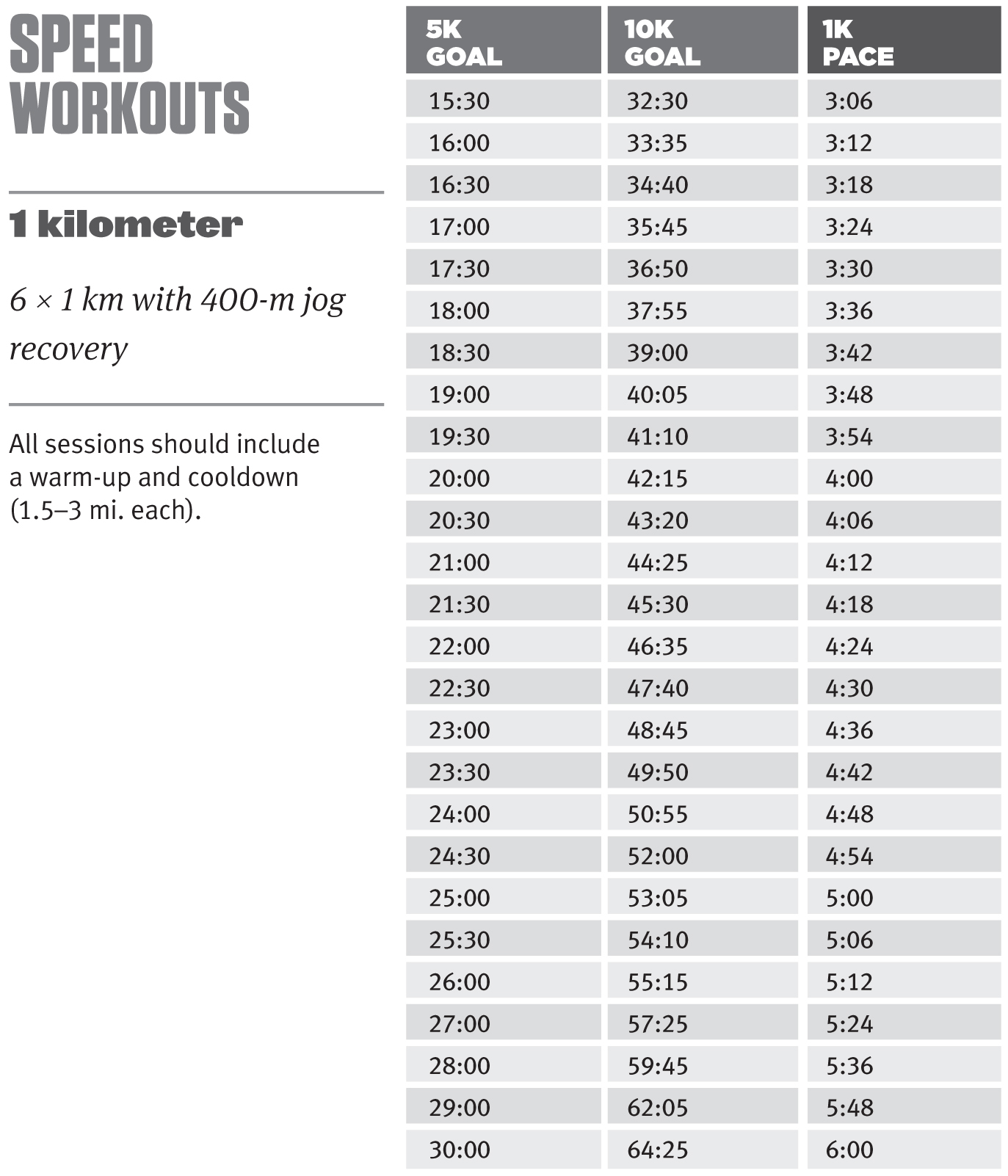

The speed sessions that are utilized throughout the Hansons Marathon Method are provided in tables below. Typically, the schedules start with the lower-duration repeats (10–12 × 400 meters) and work up to the longer-duration repeats (4 × 1200 meters and 3 × 1600 meters). Once the top of the ladder is reached (from the shortest- to the longest-duration workouts) you are then free to do the workouts that fit best for your optimal development.

If you’re new to speed work, we strongly encourage you to join a local running group. Coaches and more experienced runners can take the guesswork and intimidation out of those first speed workouts by showing you the ropes. Additionally, a local track will be your best friend during this phase, as it is marked, consistent, and flat.

Below is an outline of how speed workouts build on one other in the Advanced Program (the Beginner Program is similar but has fewer speed sessions, and the Just Finish Program does not have speed workouts). To determine the correct pace for your speed workout, use the pace charts that follow. Find your goal pace for 5K or 10K and run the designated interval as close to that pace as possible. Remember: Each session should include a 1.5–3-mile warm-up and cooldown.

Week 1: 400s

Week 2: 600s

Week 3: 800s

Week 4: 1 kilometer

Week 5: 1200s

Week 6: Ladder

Week 7: 1600s

Week 8/9: Repeats sessions of 800–1600 meters.

Decoding Speed Workouts

2-mile WU

6 × 800 m @ 5K pace with 400-m jog recovery

2-mile CD

Veterans of the sport and those who ran high school or college track might understand this workout immediately. For those who have never done interval workouts, it may appear to be a foreign language. Let’s break it down:

2-mile WU: 2 continuous miles of easy running to warm up the body and prepare it for the hard workout.

6 × 800 m @ 5K pace with 400-m jog recovery: You will run 800 m (roughly a half mile) at your 5K goal pace, then, without stopping or walking, run 400 m (roughly a quarter mile) at an easy recovery jog. After the recovery jog, you’ll run another 800 m at 5K pace, followed by another 400-m jog recovery. Repeat until you’ve run six 800-m segments at 5K pace.

2-mile CD: 2 continuous miles of easy running to cool down and shake out the legs after the hard workout.

Note: Warm up/cool down 1.5–3 miles each.

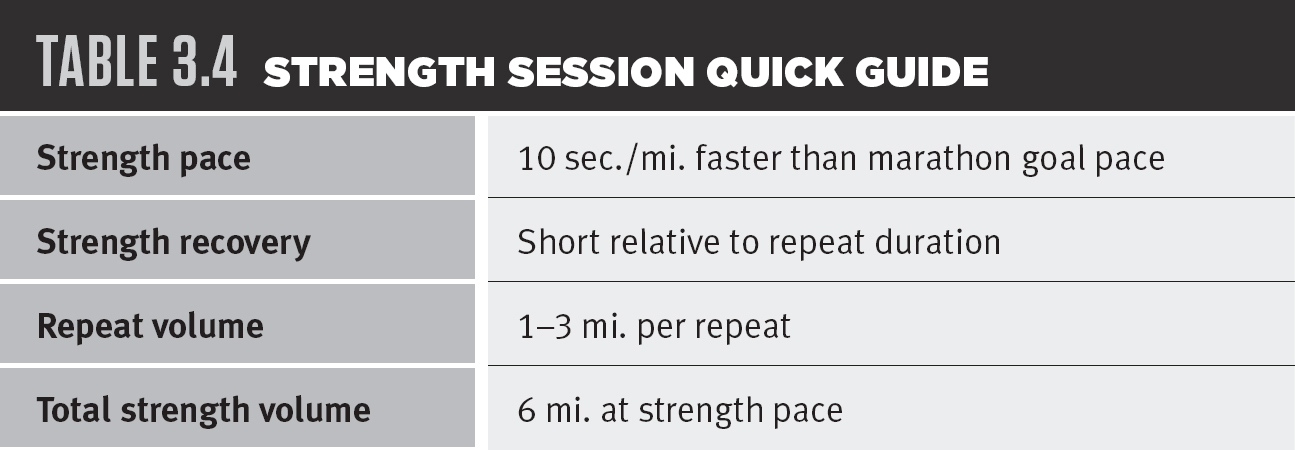

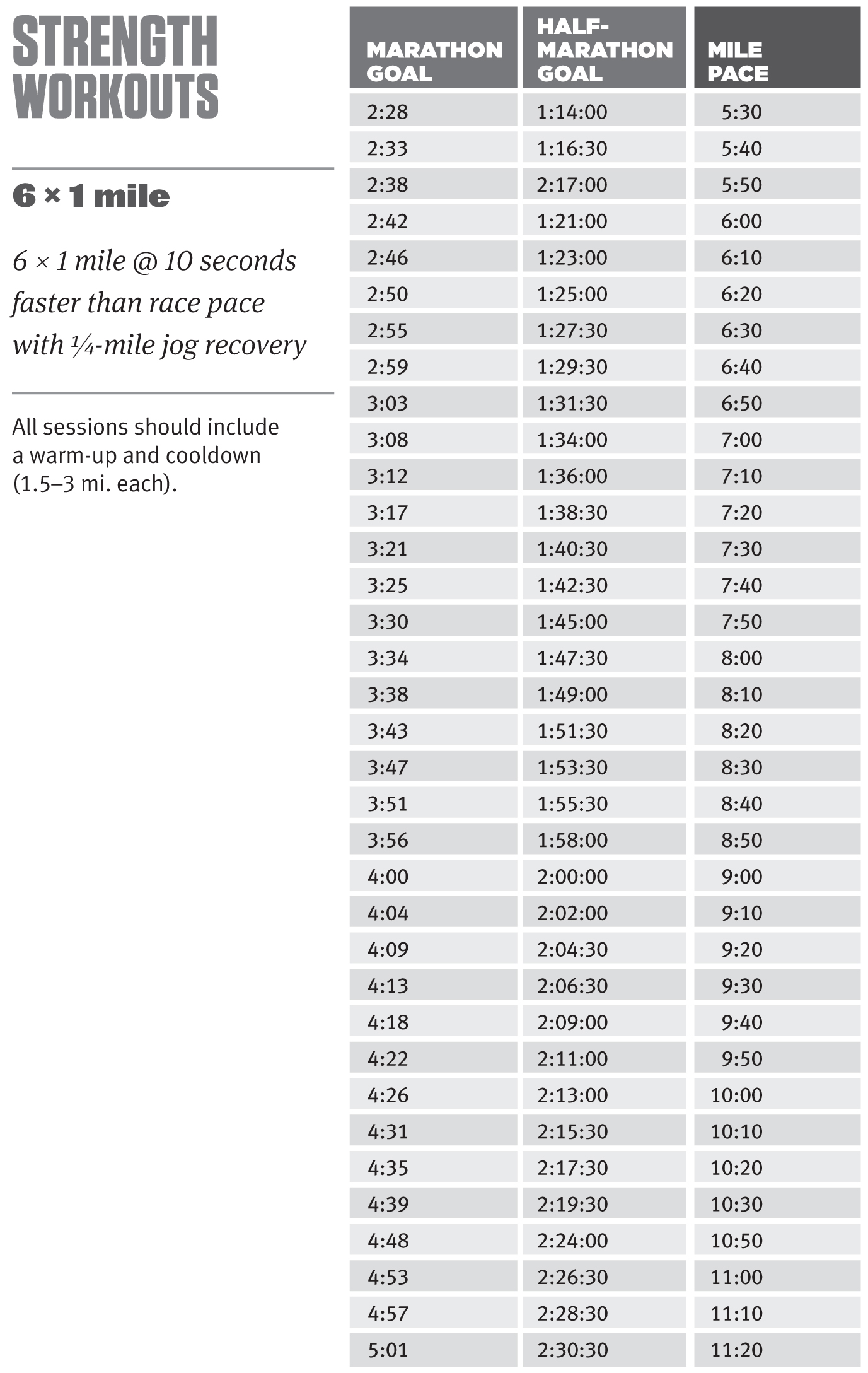

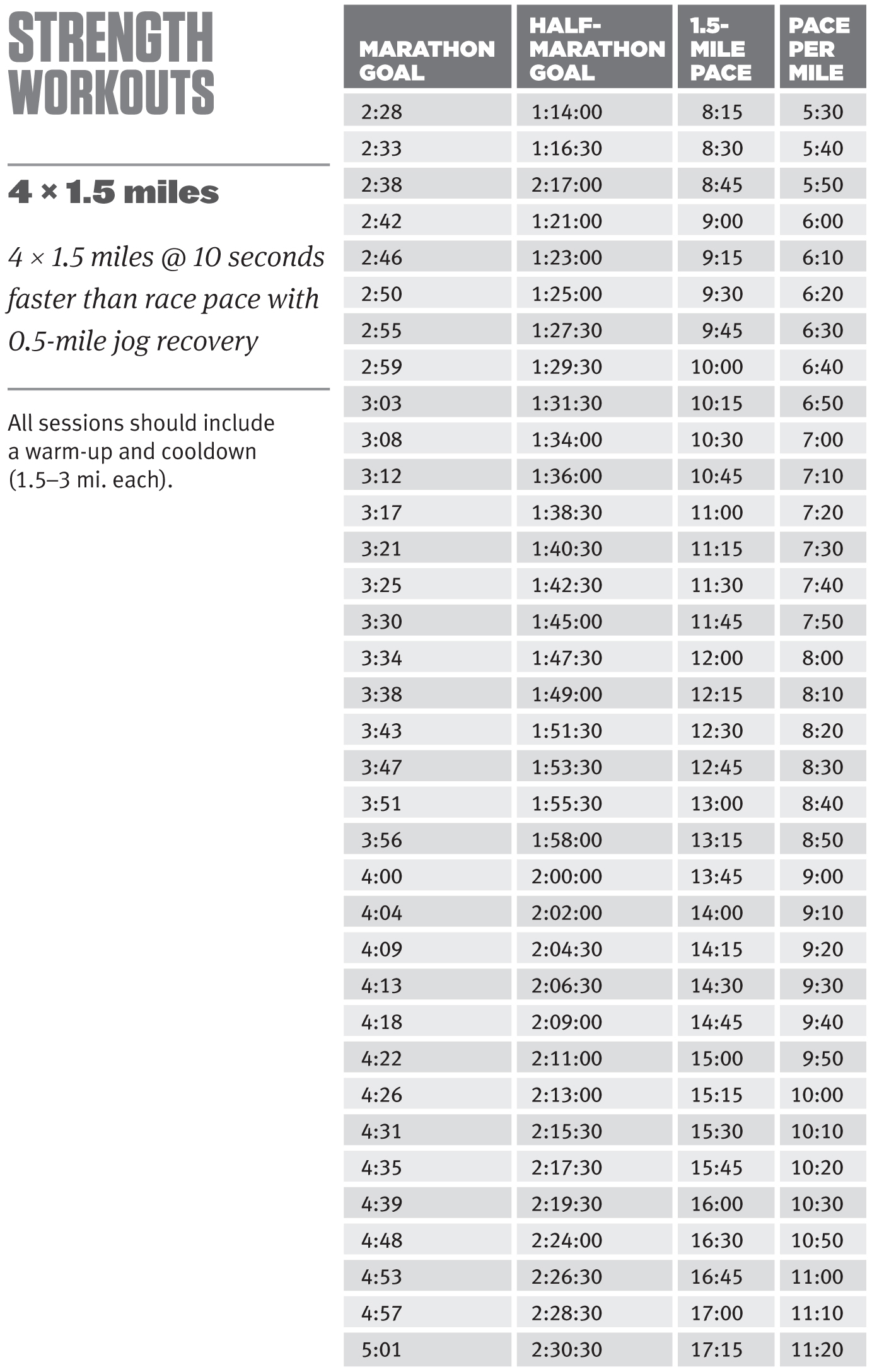

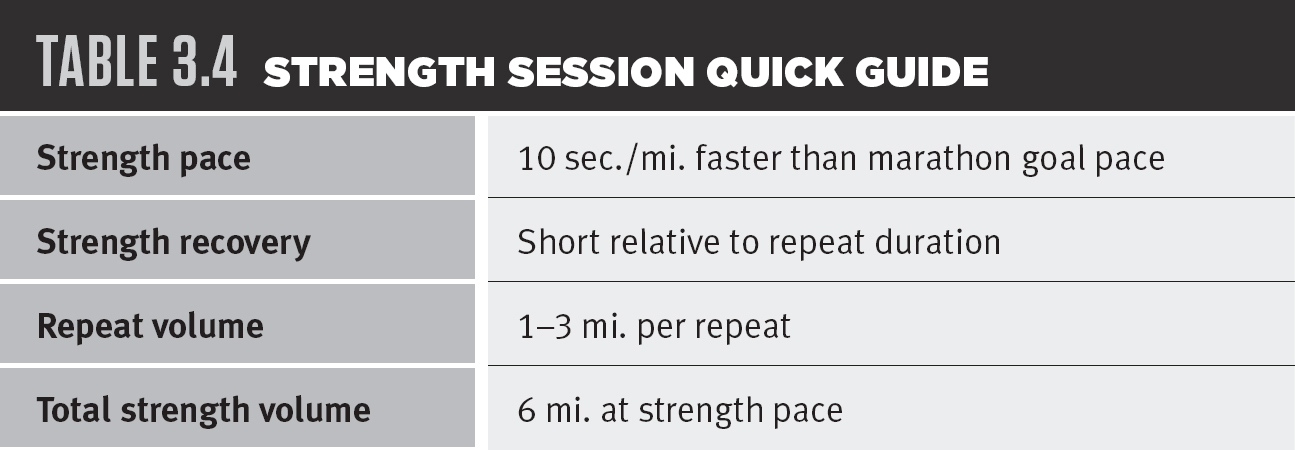

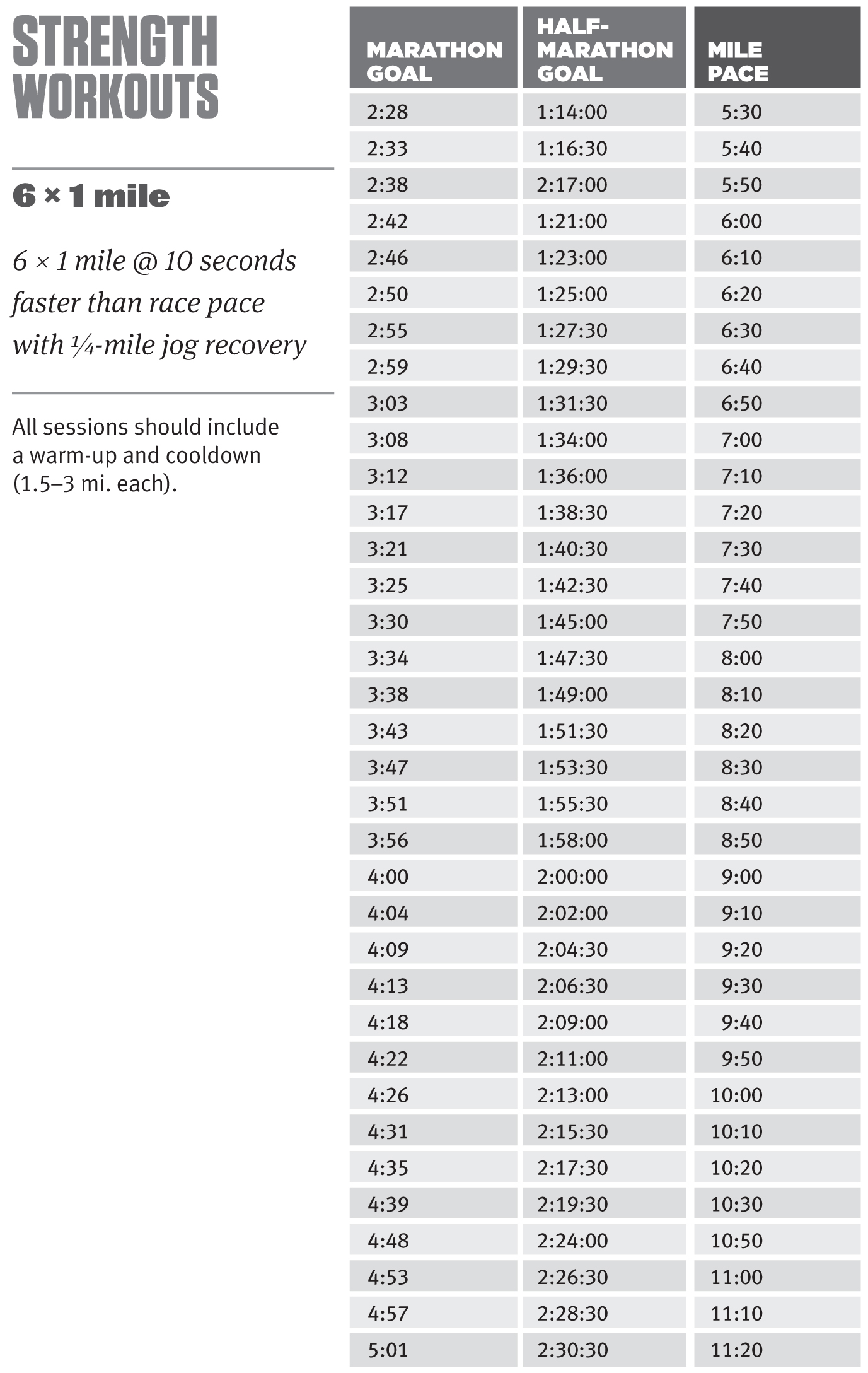

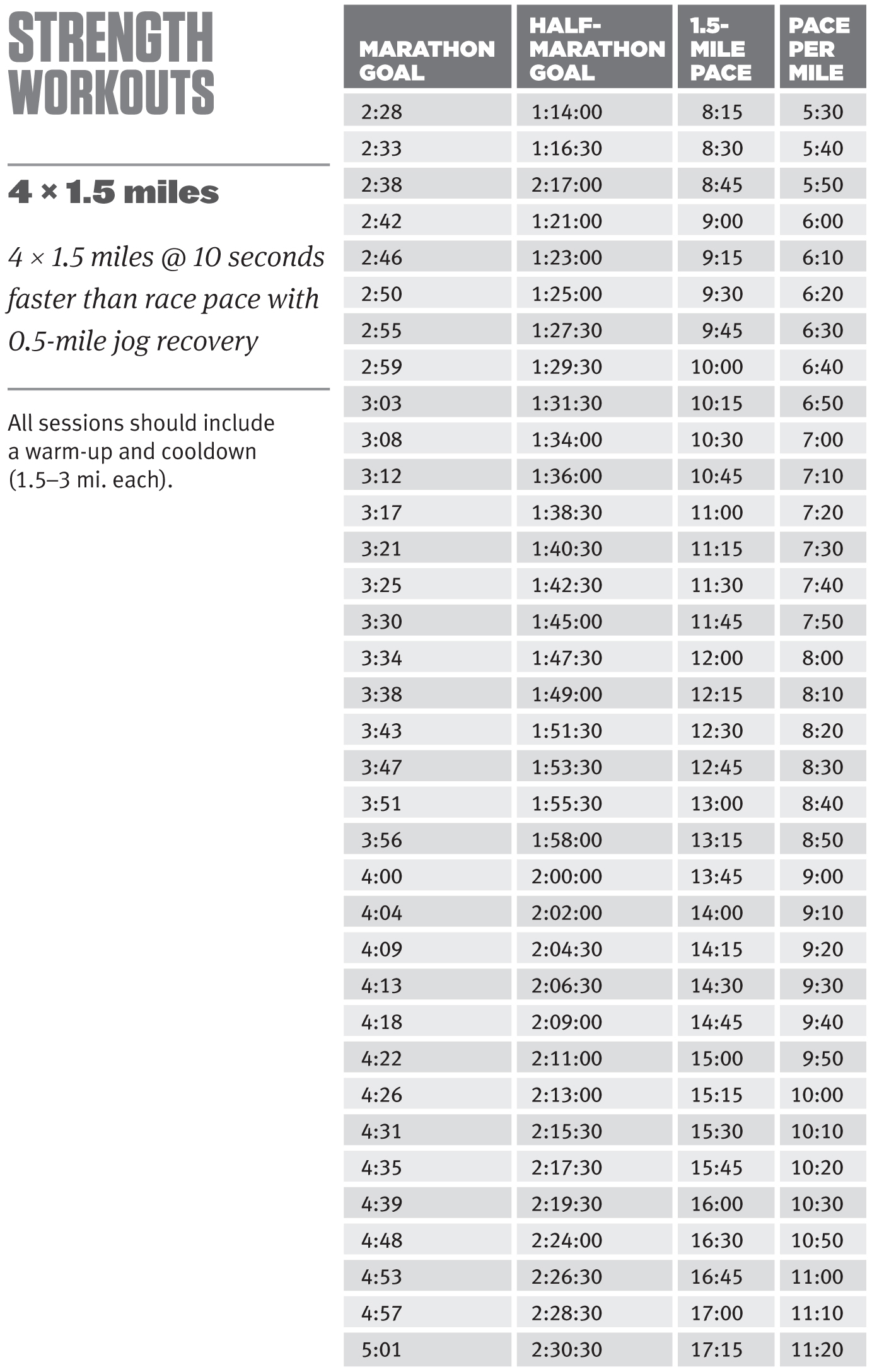

STRENGTH WORKOUTS

After you’ve spent a number of weeks performing periodic speed sessions, your muscle fibers and physiological systems have adapted quite well and are now ready for more marathon-specific adaptations. When strength workouts are added to the schedule, the goal of training shifts from improving the VO2max (along with anaerobic threshold) to maintaining the VO2max and preparing the body to handle the fatigue associated with marathon running (Figure 3.6). You’ll notice that at the same time the strength segment begins, the tempo runs and the long runs become more significant. At this point, everything the runner is doing is solely focused on marathon preparation.

FIGURE 3.6 STRENGTH WORKOUT BENEFITS

When we talk about strength workouts, we aren’t referring to intense sessions in the weight room, pumping iron and flexing muscles. Strength workouts are runs that emphasize intensity, rather than volume, with the goal of stressing the aerobic system at a high level. While the speed sessions are designed to be short enough to avoid lactate accumulation, the strength sessions are meant to force the runner to adapt to running longer distances with moderate amounts of lactate accumulation.

The Physiology of Strength Workouts

Over time, strength sessions improve anaerobic capacities, which will allow your body to tolerate higher levels of lactic acid and produce less of it at higher intensities. While your body may have shut down in response to the lactic acid buildup at the beginning of training, strength sessions help your muscles learn to work through the discomfort of lactic acid accumulation. Additionally, strength sessions help train your exercising muscles to get better at removing lactic acid, as well as contributing to improving your running economy and allowing you to use less oxygen at the same effort. Strength workouts also spur development of something called fractional utilization of maximal capacity. In practical terms, this allows a person to run at a higher pace for a longer period of time, which leads to an increase in anaerobic threshold. For the marathon, this means that glycogen will be conserved, optimal marathon pace held longer, and fatigue delayed.

These adaptations all begin with an increase in the heart’s ventricle chamber size. During a strength workout, the heart is required to pump faster and with more force than during easier runs. While it is not being worked quite as hard as during a speed session, it works at a fairly high intensity for significantly longer. The end result is a stronger heart muscle with a larger chamber area, which means an increased stroke volume. (The stroke volume is the amount of blood pumped from the left ventricle per beat.) The benefit of this is that more blood is sent to the exercising muscles, and more oxygen is delivered. In addition, strength workouts help to involve the intermediate muscle fibers, increasing their oxidative capacities. Within the muscles, less lactate ends up being produced at faster speeds, and the lactate that is produced is recycled back into usable fuel. The practical purpose of all this is that running faster paces, especially near anaerobic threshold, begins to feel easier, you become more economical, and your stamina increases.

Strength Guidelines

For most runners, the strength repeats will fall somewhere between 60 and 80 percent of VO2max, which will be slower than the speed sessions. However, while the speed sessions are relatively short (3 × 1600 m) with moderate recovery, the strength sessions are double the volume (e.g., 6 miles of higher-intensity running) with much shorter relative recovery. Strength workouts are designed to be run 10 seconds per mile slower than goal marathon pace. If your goal marathon pace is 8:00 minutes per mile, then your strength pace will be 7:50 per mile. The faster the runner, the closer this corresponds to half-marathon pace, but for the novice, this pace is between goal marathon pace and half-marathon ability. Although this may not seem like a big increase in pace, take a look at overall marathon times and you’ll see that it makes a significant difference. For example, if your goal pace is 8:00 minutes per mile, you will finish around 3:30. However, if you run 7:50 per mile, just 10 seconds faster per mile, you will finish in 3:25. This faster overall time brings along with it a large increase in lactic acid. Even though the strength workout may not feel hard from an intensity standpoint, the volume, coupled with short recovery periods, is enough to stimulate lactic acid accumulation and make way for positive adaptations. Refer to Table 3.4 for a quick guide to strength sessions.

Recovery is key to the success of your strength sessions. In order to maintain a certain level of lactic acid, the recovery is kept to a fraction of the repeat duration. For instance, the 6 × 1-mile strength workout calls for a recovery jog of a quarter mile. If the repeats are to be done at 8-minute pace, the quarter-mile jog will end up being between 2:30 and 3:00 minutes, less than 50 percent of the duration of the intervals. Since these are less intense intervals, you may be tempted to exceed the prescribed pace, but keep in mind that the adaptations you’re looking for specifically occur at that speed, no faster.

Strength workouts cover a lot of ground. When gearing up for these sessions, consider finding a marked bike path or loop to execute them. While a track can be used, the workouts can get monotonous and injury is more likely. Remember to always include 1.5 to 3 miles of warm-up and cooldown.

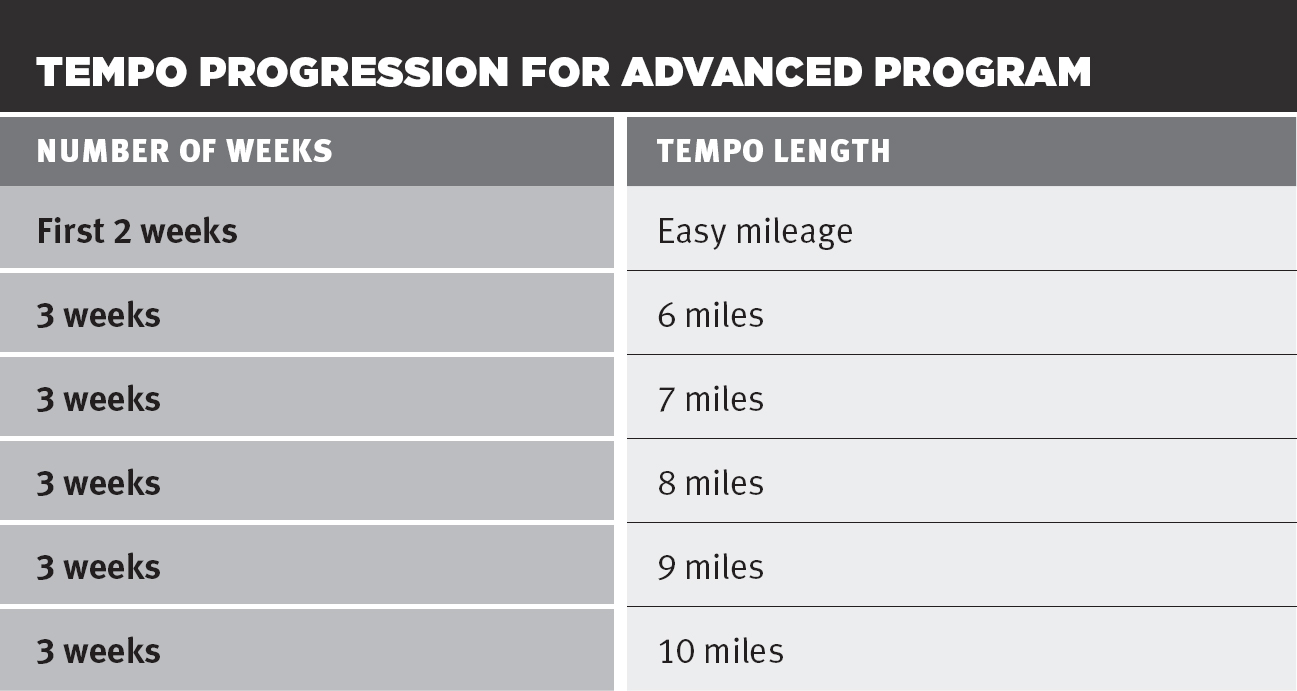

TEMPO WORKOUTS

The majority of runners who have trained for a distance race have encountered tempo workouts. They are a staple of all endurance training plans. Tempo runs have been defined numerous ways, but in the Hansons Marathon Method, a tempo run is a marathon-pace run. These runs will help you get a feel for what it is like to run race pace through a variety of conditions. Over the course of training, your tempo runs will span a number of months, requiring you to maintain race pace through an assortment of challenges and circumstances.

Internalizing pace is one of the most difficult components of training. If you feel great at the start line and go out 30 seconds per mile faster than you planned, you’ll likely hit the halfway point ready to throw in the towel. No significant marathon records have been set via a positive split (running the second half slower than the first). Put simply, if you want to have a successful marathon, you are better off maintaining a steady pace throughout the entire race, rather than following the “fly and die” method. Tempo runs teach an important skill: control. Even when the pace feels easy, tempo workouts train you to hold back and maintain. Tempo runs also provide a great staging ground for experimenting with fluids, gels, and other nutrition. Since you’ll be running at marathon pace, you will get a good idea of what your body can and cannot handle. The same goes for your gear. Use the tempo runs as dress rehearsals to try various shoes and outfits to determine what is most comfortable. Regardless of training, these things can make or break your race; tempo runs provide perfect opportunities to fine-tune your race-day plans.

FIGURE 3.7 TEMPO WORKOUT BENEFITS

The Physiology of Tempo Workouts

In the same way that easy and long runs improve endurance, so do tempo workouts. Although tempo days are faster than easy days, they are well under anaerobic threshold and thus provide many of the same adaptations. The longer tempo runs also mimic the benefits of long runs since the aerobic system is worked in similar ways. Specifically, from a physiological standpoint, the tempo run has a great impact on running economy at your goal race pace. One of the most visible benefits of this is increased endurance throughout a long race.

The tempo run has many of the same benefits as the strength workout, minus those that come from recovery between sets. Also, since it is slower than a strength workout, it elicits more aerobic benefits, similar to the long run. With tempo runs, the ability to burn fat is very specific to the workouts. The intensity is just enough that the aerobic system is challenged to keep up, but it’s slow enough that the mitochondria and supporting fibers can barely keep up.

Over time it is the tempo run that will dictate whether or not you have selected the right marathon goal. With speed and strength sessions, you can in one sense “fake” your way through as a result of the relatively short repeats and ensuing breaks in between. However, with a tempo run, there is no break and if you are struggling to hit the correct pace for long tempo runs, then there may be a question as to whether you can hold that pace for an entire marathon.

Perhaps the greatest benefit that tempo runs offer is the opportunity to thoroughly learn your desired race pace through repetition. With time, your body figures out a way to internalize how that pace feels in heat, cold, rain, snow, and wind, which is incredibly valuable on race day. When runners cannot tell if they are on pace or not, then the tendency is to be off pace (usually too fast), setting their race up for unavoidable doom. Learning your pace and the feel of that pace can make the difference between a good race and a bad race.

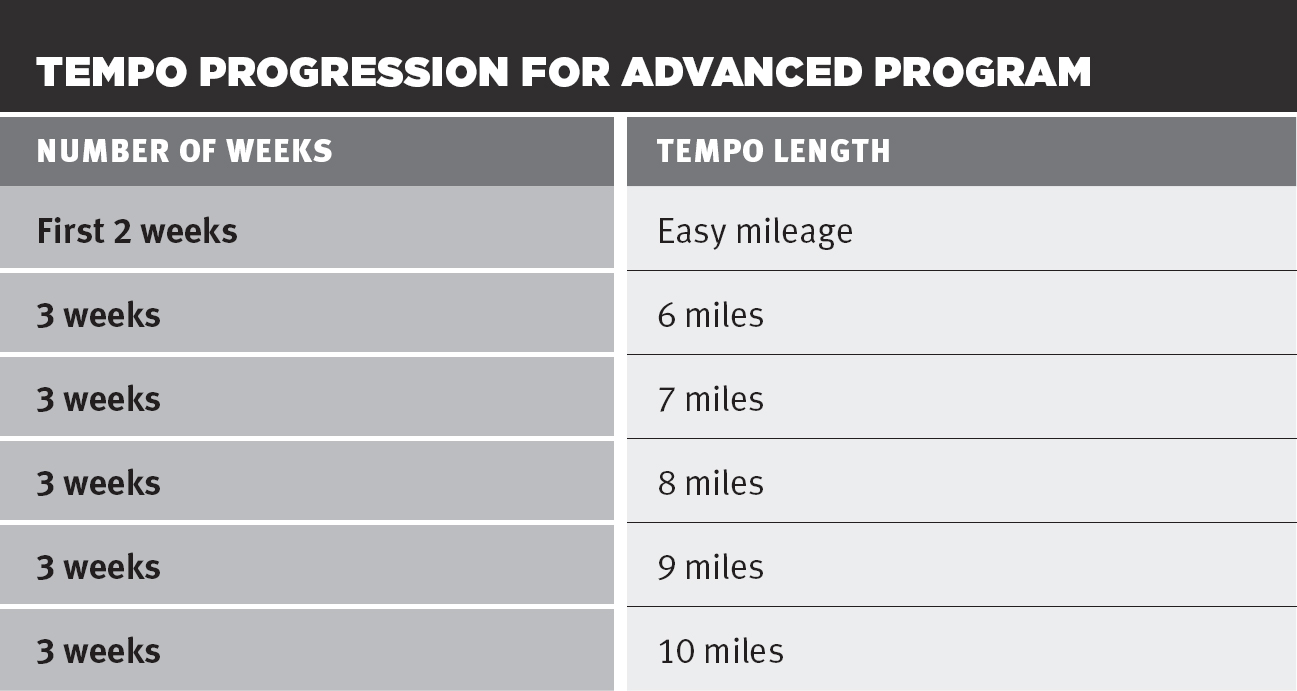

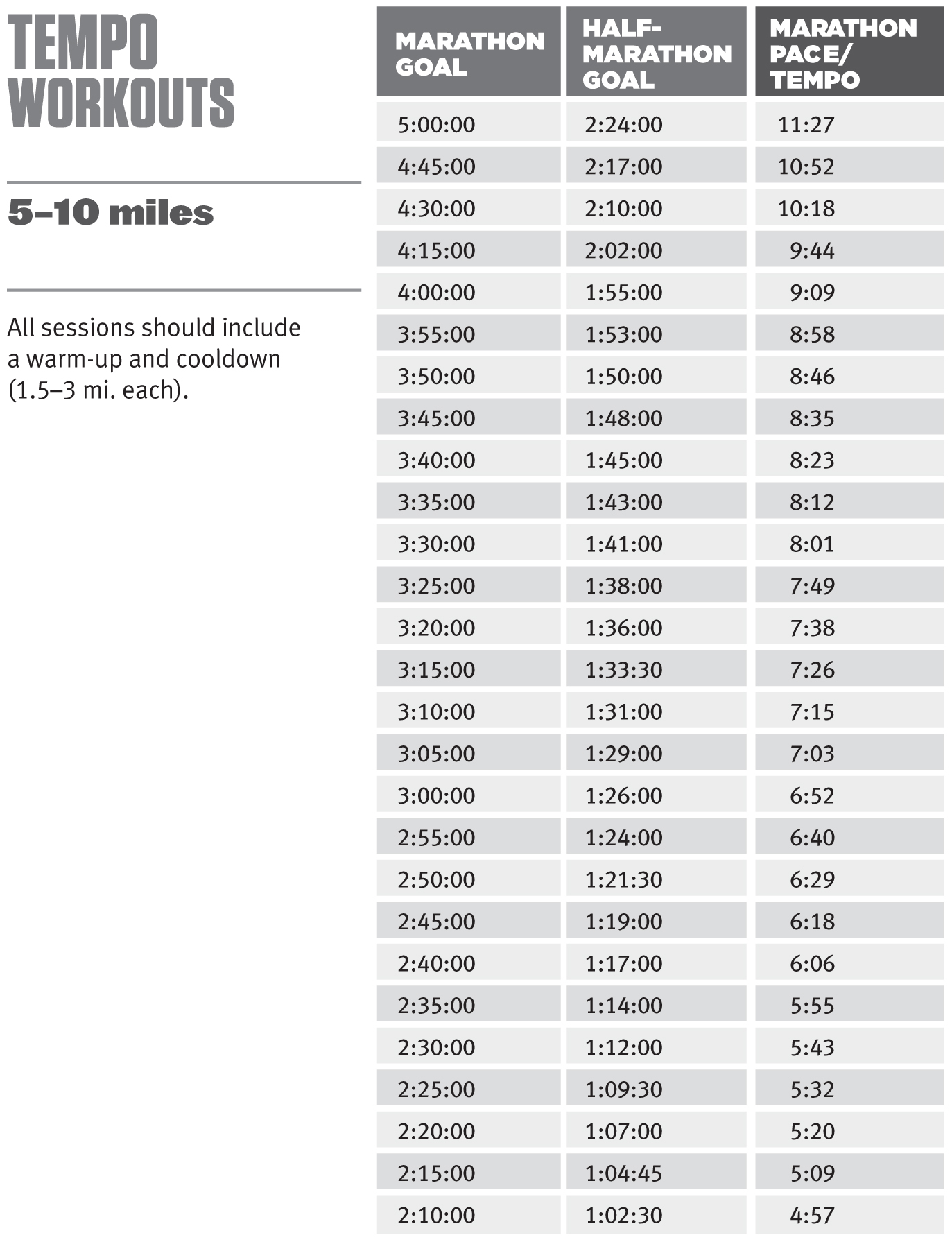

Tempo-Workout Guidelines

In the Hansons Marathon Method, the tempo run is completed at goal marathon pace. For many other coaches, a tempo run is much shorter at paces closer to strength pace, but for our purposes, tempo and marathon pace are interchangeable. The pace should remain at goal pace. Never hammer a tempo run because it feels “easy.” Not only are you compromising physiological gains, but you’re also not learning to be patient and internalizing pace. It will take a good number of tempo workouts before you fully internalize the pace and can regulate your runs based on feel. What does change throughout training is the distance of these workouts. Tempo runs are progressive in length, adjusting every few weeks, increasing from 4 miles for a beginner and 5 miles for an advanced runner to 10 miles over the last few weeks of training. As an advanced runner begins to reach the heaviest mileage, the total volume of a tempo run, with a warm-up and cooldown, can tally 12–14 miles and approach 90 minutes in length (see tables below).

With the long run looming after a tempo run, that 16-miler might look a lot tougher than it did initially. This is a prime example of how the Hansons Marathon Method employs cumulative fatigue. Rather than sending you into the long run feeling fresh, we try to simulate the last 16 miles of the marathon, and there’s nothing like a tempo run to put fatigue in your legs.

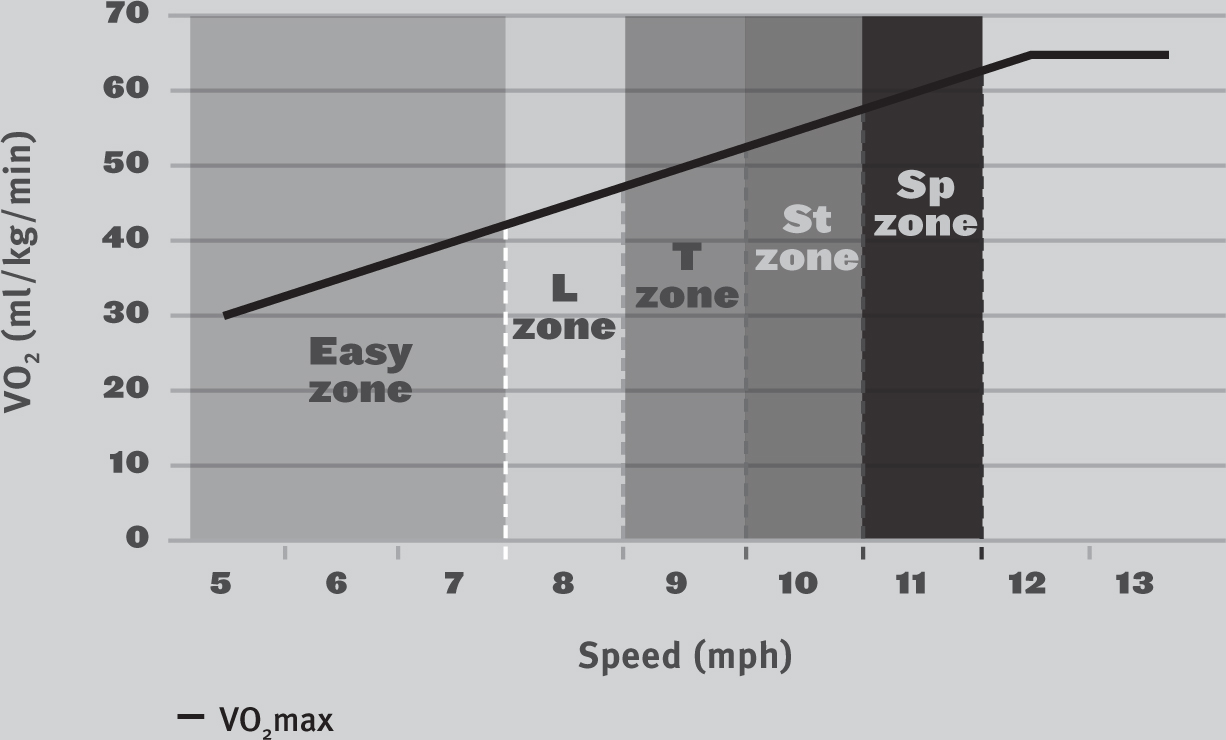

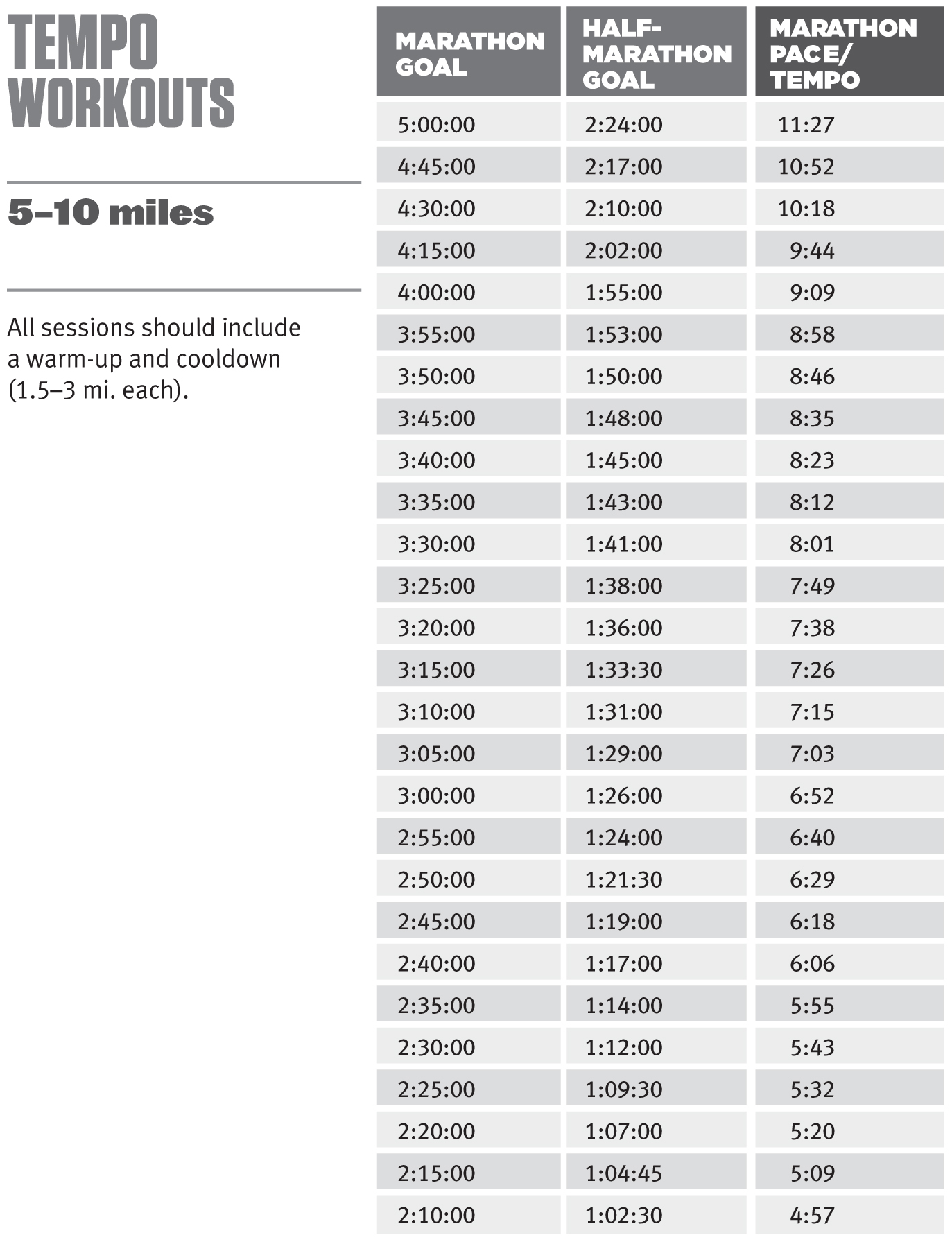

How to Pace Workouts

To help you better understand the intensity at which you should be running during the various components of the training plan, check out Figure 3.8. The diagonal line represents a sample VO2max of a runner. The first line (Easy) on the left is for the easy running days and represents everything under the aerobic threshold. It is the largest, but also the slowest area. The next zone (L) is the long run and represents the fastest paces a person should run for the long run, but could also represent the fastest of easy days for beginners. The middle zone (T) denotes ideal tempo pace, and therefore, marathon goal pace. It is above aerobic threshold, but below anaerobic threshold. The strength zone (St) represents the high end of the “lactate” section, as strength runs should fall just below anaerobic threshold. Finally, there is the speed zone (Sp) that represents where speed workouts should fall, which is just below VO2max for optimal development.

FIGURE 3.8 PACE VERSUS INTENSITY

The speed at which you are running dictates which zone you are in.

With this continuum in mind, it becomes clear why running faster than you’re instructed to run compromises development. Not only do you miss out on the benefits the workout was meant to provide when you go too fast, but you also increase fatigue. The essential point is this: Paces are there for a specific reason, and while some runners feel that paces sometimes hold them back, in reality proper pacing is what will propel you forward in the end. Fight the temptation to buy into the “if some is good, more is better” mentality and keep in mind the specific goal of that particular workout.

The Taper

Although we aren’t generally in the business of telling folks to run less, cutting mileage and intensity is actually an integral part of marathon training when scheduled at the right times. For instance, while you may feel tired from the increased training two months into the program, avoid taking a day off and cutting your mileage that week. That is the wrong time, as it interferes with the foundational element of cumulative fatigue. However, when you reach the final stretch of training, your goal is to recover from all that work you put in, while also maintaining the improvements you made over the past few months. This is the right time to taper, or reduce your training volume, and it’s one of the key steps in good marathoning.

The mistake many runners make with their tapering period is that they cut everything from training, including mileage, workouts, intensity, and easy days. In the same way we instruct you not to add these components too soon, we also suggest not abruptly cutting them out. When runners subtract too much training too quickly, they often feel sluggish and even more fatigued than they did when they were in their peak training days. There’s nothing worse than going into an important race feeling more tired than you did during training, and a proper taper is the key to avoiding this. By cutting the training back in a gradual manner, you’ll feel fresh and ready to race.

An SOS workout takes about 10 days to demonstrate any physiological improvement. That’s right, it takes more than a week before you reap any benefits from a hard run. If you look at the training plans in the Hansons Marathon Method, you’ll notice that the last SOS workout is done 10 days prior to the marathon, because after that point, SOS workouts will do nothing but make you tired for the big day. We also implement roughly a 55 percent reduction in overall volume the last seven days of the program. You will still run the same number of days per week, but with daily mileage reduced. Why the same number of days? Kevin and Keith liken it to being used to getting six hours of sleep every night and then suddenly getting 12 hours. You will feel pretty groggy the next day, even though you’re well rested. The same can be said for being accustomed to running six days a week and then abruptly going down to only three or four days. It’s a shock to the body. By continuing to run fewer miles, but still running every day, you reduce the number of variables that are adjusted. Instead of reducing frequency, volume, and intensity, you are tinkering only with the last two. Many other marathon training plans not only cut too much out of the schedule, but they also prescribe a taper of two to four weeks, causing a runner to lose some of those hard-earned fitness gains. By reducing the taper to just a 10-day period, you cut down on the risk of losing any of those gains, while still allowing adequate time for rest and recovery.

From a physiological standpoint, the taper fits well with the principle of cumulative fatigue, as the training program does not allow you to completely recover until you reach those final 10 days. Over the last couple months of the program, some of the good hormones, enzymes and functions in your body have been suppressed through incomplete recovery, while the by-products of fatigue have simultaneously been building. With reduced intensity and volume during the taper, these good functions flourish. Meanwhile, the by-products are allowed to completely break down and the body is left in a state of readiness for your best performance. We always warn runners not to underestimate the power of the taper. If you are worried about your ability to run a complete marathon at the pace of your tempo runs, consider this: The taper can elicit improvements of up to 3 percent. That is the difference between a 4:00 marathon and a 3:53 marathon. I don’t know about you, but I’d be happy with a 7:00-minute improvement on my personal best.

Training Intensity Chart

To be utilized in determining how fast to run your workouts, Table 3.5 demonstrates pace per mile based on various goal marathon times. For easy runs, refer to the Easy Aerobic A and Easy Aerobic B columns. The faster end of the long-run spectrum is indicated in the Moderate Aerobic column. The Marathon Pace is the speed at which your tempo runs should be run. The Strength column will be your reference for strength workouts, and the 10K and 5K columns for your speed workouts. Keep in mind that actual 5K and 10K race times are going to be more accurate than this chart. If you have raced those distances, use your finishing times to guide your speed workouts. Our goal here is to provide you with guidance in your workouts, to help keep you focused and make the correct physiological adaptations throughout training.

Thoughts on Heart Rate Training

We don’t prescribe by heart rate. We’re not against heart rate (HR); rather we are in favor of treating all methods, from GPS devices to strength training to heart rate to shoes, as mere tools. Focusing too much on any one tool can throw off the balance in your training. Yes, heart rate training can have a place in your Hansons Marathon Method training—just not a primary one on your speed, strength, tempo, and possibly your long runs. There, pacing calls the shots.

With our training, pace, not heart rate, is key. Why? Because the entire system is based on a goal and/or race pace. In our system, easy runs are based on an amount of time slower than goal marathon pace. Tempo runs are based on that goal pace, and strength is a set amount faster than that goal pace. The majority of runners we coach have a time goal in mind. It may be a Boston Qualifier, a sub-2:30 or sub-4:00, or an Olympic Trials qualifier. To run the pace required to meet your time goal becomes incredibly important. If you can’t run those paces, then you can’t reach your goals. So is it more important that you know you’ve kept your heart rate at 75 percent or that you have run the 8:00-minute-per-mile pace you need to run your BQ? Let me just say, I haven’t heard too many people cry out in joy at the finish line, “Yes! I kept my heart rate under 150!”

If you feel HR training is the way to go, then here are a couple of tips.

Be certain what your max heart rate is. Have it tested (a VO2max test), and also get the HR ranges for your thresholds. The old standby equation to find HRmax (220 minus your age) is sufficient when looking at a large sample of people, but its individual accuracy can be questionable. Testing eliminates some of the guesswork.

Don’t focus solely on HR; use all your tools. For example, GPS watches with HR monitors make this easy. Consider your tempo run. If you plan to run 8:00-minute miles, then it is helpful to know what your heart rate tends to be for those runs. If you see that heart rate trend climbing, take note. Are you feeling sick? Maybe it’s something; maybe it’s not. Use all the tools you have at hand—including your instincts—to know if you are training too hard. By relying on only one piece of data, you are at the risk of all kinds of variables. Better to look at the whole picture.

The main reasons we use heart rate are to gauge intensity and to monitor overtraining. In these regards, does it provide useful information? Potentially, but more in terms of tracking trends than in day-to-day numbers. If you use it, consider using it as an add-on to monitor your paces and give you an idea if you are getting fit enough to race what you want to. Should you wear a monitor every day? I don’t recommend that. But nor do I recommend wearing a GPS every day. For those starting out, we know there are a lot of unknowns: Am I too fast? Too slow? What exactly is too fast or slow? Am I improving? These are legitimate questions. Having something to measure and provide feedback is great. However don’t let that reliance keep you from learning to listen to what your body is telling you.

![]()