In Philadelphia, Wanamaker was the King. And he felt that if he could make it in New York, he could make it anywhere.

—Herbert Ershkowitz, professor, Temple University

On September 29, 1896, John Wanamaker assumed control of New York’s landmark A.T. Stewart store at Broadway and Ninth Streets. The purchase price was rumored to be around $2 million. He was now the head of his hero and mentor’s business. With the acquisition of the Stewart store, Wanamaker was anxious to bring his level of merchandising expertise to New York and to hopefully become a nationally recognized merchant pioneer. He felt he could bring something different to New York City. On November 17, 1896, the New York Wanamaker store officially opened. The company promised that it would “simply keep a good Wanamaker store with no startling innovations.” Wanamaker wanted to replicate the success of the Philadelphia store in New York, so he had his department heads spend three days in Philadelphia and three days in New York until the business became “thoroughly systematized.” Rodman was called home from Paris and put in charge of the New York store.

Also in 1896, Wanamaker inaugurated the John Wanamaker Commercial Institute. Cadets came to both the Philadelphia and New York stores to attend classes and to learn the retail trade. In addition, they played in bands and sang in choirs. Ray Biswanger, head of the Friends of the Wanamaker Organ, felt that Wanamaker had other intentions for these Cadets. “John Wanamaker would use every holiday to have a public ceremony, and he would use these kids [in the ceremonies]. It was for the benefit of tourism. This helped make Wanamaker’s different,” stated Biswanger. Being a Wanamaker Cadet was also a symbol of prestige for young men and women in Philadelphia and New York.

Former Drexel University professor Mercia Grassi remembered her aunt telling stories about Wanamaker’s program.

My aunt became a member of Wanamakers’ Cadet Corps right after World War I. Wanamaker picked the most elegant ladies of Philadelphia. He trained the ladies and sent them to be the sales associates at the aisle-end counters that faced the motor entrance where all of the pizzazzy men of Philadelphia came in to go to lunch. The object was’ to attract these men through these very elegant ladies so that they would want to buy for their families.

Every summer, the Cadets spent two weeks at a camp in Island Heights, New Jersey. In addition to recreational activities, the Cadets engaged in a military-style training program. Many young men graduated from the John Wanamaker Commercial Institute and became prominent citizens of Philadelphia and New York.

Unlike the Philadelphia operation, the New York Wanamaker store faced an uphill battle. An early Wanamaker publication stated “The first year’s progress was difficult because an entirely new organization had to be made and perfected.”11 Unable to gain a loyal following even from the beginning, the new store was considered too far downtown to effectively compete with stores such as Gimbels and Macy’s.

Gimbels’s new store on Herald Square offered extremely competitive prices and enjoyed the resulting strong sales.12

Wanamaker felt the competition from Gimbel Brothers in Philadelphia as well. Gimbels’s new store on Market Street made Wanamakers’ renovated depot look worn. Wanamaker worried about the safety of his Philadelphia store, wondering if it had the potential to become a firetrap. Wanamaker wanted to replace the Philadelphia store building and he wanted to add on to the New York store. He bought property around the Philadelphia site, thus eliminating any nearby competition. In 1902, Wanamaker met with famed Chicago architect, Daniel Burnham. Burnham’s legacy includes Chicago’s Marshall Field and Boston’s Filene stores. Burnham was eventually engaged to design both new stores for Wanamaker. It was decided that the Philadelphia store would be rebuilt in three stages so that the store could continue to conduct business during its renovation.

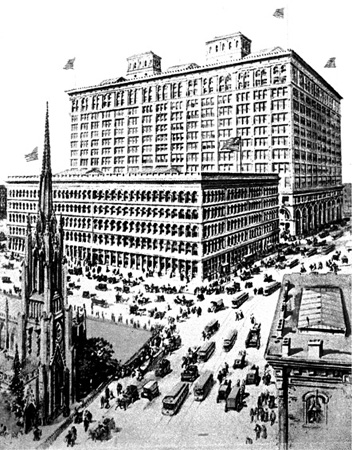

The Wanamaker’s Stores at Broadway and Eighth Street in New York City. The former A.T. Stewart building is in the foreground.Courtesy of the author.

A view of the Market Street side of the Grand Depot in Philadelphia from 1902. City Hall is in the background. Courtesy of PhillyHistory.org, a project of the Philadelphia Department of Records.

A matchbook image of the Bridge of Progress that connected the two Wanamaker’s stores. Courtesy of the author.

Burnham designed a grand addition to the New York store. The two buildings were to be connected by a Bridge of Progress. Problems with finances and zoning permits caused lengthy construction delays for the two construction projects. However, John Wanamaker New York opened with great fanfare on October 1, 1907, two years after its original projected date of completion. Over 200,000 people visited Wanamaker’s during its first three days. In addition to the new modern addition, the former A.T. Stewart store now featured a magnificent rotunda and staircase. This newly completed structure contained thirty-two acres of floor space and employed 6,000 workers. John’s son, Rodman, helped outfit the store with works of art. A Wanamaker publication proudly announced that the new addition contained “eight spacious floors loaded with the best makes of reliable merchandise selected especially for New York sales.”13

In spite of the initial success of the New York opening, John Wanamaker entered a very critical time. In February 1907, Wanamaker’s “magnificent summer residence,” Lindenhurst, was destroyed in a massive fire. Lindenhurst was filled with some of Wanamaker’s most prized pieces of art. As the building burned, firemen and neighbors tried desperately to save many of the priceless artifacts. Over eight hundred pieces of art were quickly removed from the burning structure. Some paintings were cut from their frames. The fire attracted many spectators and unfortunately many of the paintings were hastily thrown into the snow and trampled on by those watching the flames.14 The fire at Lindenhurst destroyed many of Wanamaker’s prized antiques and tapestries. Also destroyed in the fire was a sentimental gift that John had given to his son Rodman—a small pipe organ.

The Philadelphia store was only half built when the financial panic of 1907 hit. In March 1908, John lost his oldest son, Tom. He relied on his son, Rodman, to see him through this hard time. Rodman, who was in charge of the New York store, was summoned to Philadelphia. The panic hurt sales at both stores. Construction delays continued at the Philadelphia store, as some bills went unpaid. But John and Rodman were able to weather the financial storm and the two Wanamakers soon opened one of America’s greatest department store buildings.