Wanamakers had the history of allowing people not to be solicited and hustled in order to make a sale. The store invited people to come in, browse, and just enjoy a walk around the store.

—Christopher Kellogg, Wanamaker family member

The Wanamaker family was not as interested in being merchants as they were interested in getting a good return on the business. They had seats on the Board of Trustees of the Rodman Wanamaker Trust and they received salaries for serving in this manner. “The family pushed them [the management of the store] to limit the expenditures that were required for the continuance or the further expansion of the business,” says Wanamaker historian William Zulker.35

The Philadelphia Wanamaker’s continued to dominate the Market Street business district. It was home to the Crystal Tea Room, Philadelphia’s largest dining room. Known formally as the Great Crystal Tea Room, the restaurant could serve fourteen hundred guests at a time. It was modeled after the tearoom in the home of Robert Morris, a financier of the American Revolution. The Crystal Tea Room was famous for oak floors and oak columns in Circassian brown finish as well as its signature crystal chandeliers. This famous restaurant covered twenty-two thousand square feet on the store’s eighth floor. It had the capacity to cook seventy-five turkeys at one time. Jan Whitaker, author of Tea at the Blue Lantern Inn and Service & Style—How the American Department Store Fashioned the Middle Class says, “a tea room in a department store was a place unlike the average restaurant. It had a degree of luxury but it was quiet, not showy.”

A menu cover from Wanamaker’s famous Crystal Tea Room. Courtesy of the author.

In regard to the Wanamaker’s Crystal Tea Room, Whitaker says:

From the day the Crystal Tea Room opened, its aim was to surround diners with comfort andfirst-rate quality of the sort enjoyed by the solid middle-class citizens of Philadelphia. Tables were set with French china, hand-hemmed damask napkins, and Colonial reproduction silverware. Crystal chandeliers lit the room brilliantly, no doubt in striking contrast to many customers’ homes still using gaslight before World War I. A 1950 menu signals patrons’ simple tastes. Still among the city’s largest and best eating places even then, the tea room offered humble items alongside more elaborate dishes. Fans of the deluxe could order shrimp salad or lobster thermidor but there was also plain Swiss cheese sandwiches, gelatin salads, and stewed prunes, all served with elegance. Whether homely fare or not, meals in the Crystal Tea Room remained stamped in memory as special occasions.36

The Crystal Tea Room was not the only restaurant on the eighth floor of Wanamaker’s. Adjoining the Crystal Tea Room was the moderately priced restaurant La Fontaine and the Men’s Grille.

The Philadelphia store contained the Wanamaker’s Tribout Shop. The shop “was purchased bodily in Paris by Rodman Wanamaker in 1924.”37 Located at 20 Rue des Pyramides in Paris, Tribout was an elegant salon that sold clothing for women and infants, men’s furnishings and “golf goods.” Promotional information referred to the Tribout Shop as “a shop whose like you may never again know.” Its distinctive merchandise for women combined the offerings of leading French and American designers “all with the unmistakable Tribout individuality and superiority.” The Philadelphia store was also home to the Coty “Paris” Salon. The Coty Salon was located on the Main floor on the Chestnut Street side of the building. Stocked with the Coty’s signature beauty products, the salon was “dedicated to the women of Philadelphia and devoted to the arts of beauty and charm,” according to a company pamphlet. In addition to the Tribout Shop and the Coty “Paris” Salon, the Camee Candy Shop, the Jewelers’ and Silversmiths’ Hall, the famous Morgan Apothecary and one of the world’s largest bookstores were located right in the store’s Grand Court. “The Philadelphia store was the forerunner to the modern-day mall. The store carried ‘everything from everywhere for everybody.’ The only two things that they did not sell were food and fuel,” says Wanamaker historian William Zulker.38

During every Lenten season, Wanamaker’s proudly displayed two of John and Rodman’s most influential works of art. The two paintings are by Hungarian painter Michael de Munkacsy and date from 1882: Christ Before Pilate and Christ on Calvary. These two massive works of art were cut from their frames and saved during the Lindenhurst mansion fire of 1907. The Munkacsy paintings were exhibited in the Grand Court to provide artistic and spiritual inspiration to the Wanamaker customer.

Wanamaker’s returned to its menswear heritage and opened a separate eight-story Men’s Store in the Lincoln-Liberty Building located directly adjacent to the Main Store in September 1932. This store had been planned for years. Its merchandise included the most inexpensive lines of clothing for men to the most costly imported goods. Broad and Chestnut Street was the perfect address for this “climax of a dream” that helped bring London menswear sophistication to the American audience.

A promotional guide to the store proclaimed the following information about the new Men’s Store:

Crowds gather in the Grand Court to view the two Michael de Munkacsy paintings. Wanamaker’s displayed the paintings during Lent as a means of giving spiritual inspiration to its customers. Seen here is Munkacsy’s painting Christ Before Pilate. Courtesy of Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

John Wanamaker himself selected the location during his lifetime in the belief that William Penn was right when he declared Broad and Chestnut Streets as “ye center of ye city.” The opening of the store will mark one of the most powerful expressions of firm faith in the future of Philadelphia39

The Founder’s Bell was moved from its temporary home on the roof of the Wanamaker store to the top of the Lincoln-Liberty Building. The two Wanamaker buildings in Philadelphia secured Wanamaker’s place as the premiere department store in the city.

The situation in New York was quite different. The New York store was “anything but prosperous.” It was located far from the city’s retail hub and its old-fashioned business techniques were seen as “too provincial” for the New York audience. What worked in Philadelphia did not always work in New York. The store was never truly successful. “[When he was alive] John Wanamaker knew that the New York store was a mistake but he put large amounts of money into it,” says Professor Herbert Ershkowitz. Even though the store was admired for its soft-spoken salespeople and its air of quiet gentility, many New York shoppers didn’t feel it was worth their time to make a special trip to its off-the-beaten-path location at Broadway and Ninth Street.

A bird’s-eye view of Wanamaker’s Men’s Store in the Lincoln-Liberty Building. Courtesy of Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

A postcard view of the New York Wanamaker’s stores from the 1930s. Courtesy of the author.

A photograph of the ornate rotunda located in the former A.T. Stewart store from December 1930. Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

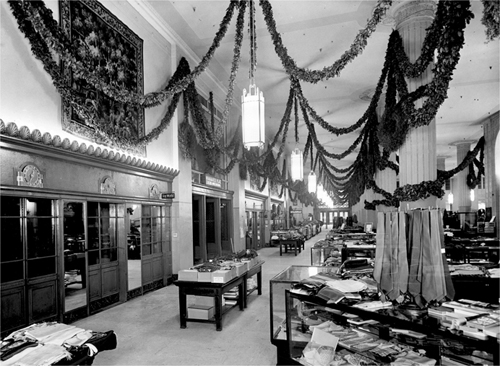

An interior view of the Wanamaker’s new building from December 1931. Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

In the mid-1930s, Wanamaker hired advertising legend Bernice Fitz-Gibbon to help draw people into the New York store. After a successful stint at Macy’s, Fitz-Gibbon was shocked when she went to work at the New York Wanamaker’s. She saw a store “with empty, cavernous aisles.”40 Because business had dropped off so significantly, the store had cut back drastically on its advertising budget. It was up to Fitz-Gibbon to find a way to “lure crowds into that lovely old deserted building too far downtown.” With her gift of prose, Fitz-Gibbon transformed Wanamaker’s advertising. Her soft-sell style of advertising had customers eager to once again step foot in Wanamaker’s. When she advertised that the New York store restaurant served lemon pie that “trembles as it’s placed on the table,” customers flocked to the store to try the special lemon pie. When Fitz-Gibbon had no money to put on a fashion show, she brought in dancing instructors from Arthur Murray, dressed them up as models, and advertised the event as “Waltz me around again, Arthur.” This revolutionary style of promotion began to draw crowds to the New York store but it also drew concern from the Board of Directors in Philadelphia.

In her book, Macy’s, Gimbels, and Me, Fitz-Gibbon writes:

I had to spend too much time and energy struggling with the heavy hand of the heavy institution, Wanamaker’s Philadelphia. The Philadelphia top brass resented my throwing out the “Sayings of the Founder,” which had been displayed for decades across the top of every Wanamaker page. They were pontifical, boresome, musty, and fusty. I am certain that old John Wanamaker himself, if he had been around, would have tossed them out. It was he who said, “I am sure I could cut out half my advertising and save money. Trouble is, I don’t know which half.”41

One of Fitz-Gibbon’s greatest successes at the New York Wanamaker’s was her promotion of the renovated Home Store. On March 31, 1937, Wanamaker’s boldly advertised “11-1/2 hours of entertainment and instruction in the new Home Store.” The new Home Store occupied four floors in the 1907 building, and Fitz-Gibbon brought musicians such as Guy Lombardo and Tommy Dorsey to serenade the crowds. Theater organist Hans Henke performed a recital on the store’s new electric Orgatron, an electric organ “that sounds almost like a pipe organ.” Sportsmen showed off the latest techniques in marksmanship and badminton in the Wanamaker Country Club on the store’s second floor. The celebration brought in hoards of shoppers and was all under the direction of Fitz-Gibbon. However, in 1940, frustrated with the Wanamaker leadership, Fitz-Gibbon left her job at Wanamaker’s and went to work transforming Gimbels.

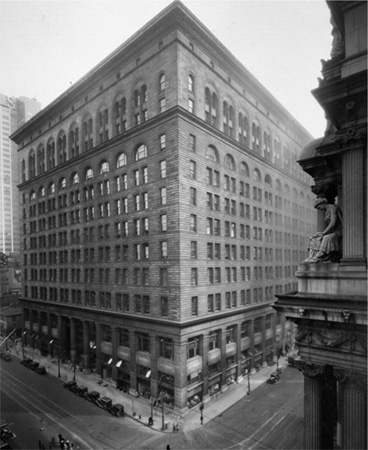

A stately view of the Philadelphia Wanamaker’s store as seen from City Hall. The photograph was taken on September 5, 1932. Courtesy of PhillyHistory.org, a project of the Philadelphia Department of Records.

Wanamaker’s missed some golden opportunities for expansion in New York City. In 1932, the Rockefellers gave Wanamaker’s an opportunity to buy a city block just off of Rockefeller Center. This would finally give Wanamaker’s the uptown presence that they so desperately needed. The board refused the offer. “They turned it down unfortunately and it was a big mistake,” says Wanamaker family member Christopher Kellogg. Some people say that that decision was the biggest mistake the company ever made.

When Metropolitan Life was building in 1940 its mixed-use development in the Bronx called Parkchester, they had reserved space for a branch department store. Metropolitan Life was anxious to have Wanamaker’s join the complex but Wanamaker’s rejected the offer as they were still looking at “other possibilities that might present themselves.” In 1944, Stevenson Newhall of the New York Board of Directors announced that the New York store had come to a crossroads and “the store must decide whether it should stand still or expand.” He cited the other lost opportunities and presented a plan: Wanamaker’s would locate a seventy-thousand-square-foot store at Forty-seventh Street and Madison Avenue. The seven-story store would offer women’s and infants’ apparel and would provide “good taste, proper prices, courteous salesmanship and service” and “would not try to imitate all of the uptown shops.”42 The board debated the proposal for almost two years but then abandoned the idea. Another golden opportunity for Wanamaker’s in New York was lost.

On November 29, 1946, Wanamaker’s opened its Liberty Street store in New York City. The store was a miniature department store without home furnishings. The three-level building carried men’s and women’s clothing, cosmetics, accessories and china. “The store was successful and profitable because it was in a financial district which didn’t have any stores,” says Wanamaker family member Christopher Kellogg. The store had a receiving window that measured four feet square. If the merchandise couldn’t fit through the window, the store didn’t carry it.43 The Liberty Street store proved to be Wanamaker’s most successful business decision in New York City.

Back in Philadelphia, Wanamaker’s continued to play the role of business and civic leader. In 1942, a War Bond Post opened right in the store’s Grand Court. When the post opened, city and state leaders gathered to show united support for the war and a rousing rendition of the Star-Spangled Banner was sung with the accompaniment of the famous Wanamaker organ.44 However, absent from the ceremony was the Cadet Corps of the John Wanamaker Commercial Institute. Wanamaker’s abandoned the institute in 1941, citing advances in public education that made the program unnecessary. In 1942, Wanamaker’s launched a Tin Can Campaign that promoted “an arsenal in their own kitchen” for Philadelphia housewives. Advertisements educated housewives how to prepare used cans for salvage. “Because the Japs control 92 percent of the world’s supply of new tin, housewives are informed, every ounce of tin now in the country must be reclaimed and re-used,” said one Wanamaker’s advertisement.45 The company contributed annually to the United War Chest Victory Campaign, donating $65,000 in 1946 alone.

A scene of the empty Philadelphia store during a practice air raid drill. Courtesy of Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The Philadelphia store quickly reopens and fills with customers after an air raid drill. Courtesy of Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Wanamaker’s was content with its business in Philadelphia. Through its art displays, musical presentations, rose shows and merchandise offerings that were geared toward any budget, the store was stable and successful. But Wanamaker’s couldn’t just sit back. There were many other large Philadelphia retailers that were all too ready to take a piece of the Wanamaker’s market share.