There was this great feeling of quality when you entered the store. Even the name of the store inspired confidence.

—Pat Ciarrocchi, news anchor, KYW-TV

By the late 1940s, most large American department stores either began opening branch stores or began planning branch stores. After the war, many Americans left cities in exchange for life in the suburbs. Retailers had to follow their customers, and the age of the suburban department store began. Layout convenience and free parking provided unlimited possibilities for department store branches. It was time for Wanamaker’s to look ahead and search out potential locations for suburban growth. Wanamaker’s set its sights on Wilmington, Delaware.

Wilmington was a fast-growing city that was grossly underserved by large department stores. The city was home to small stores such as Crosby & Hill, Kennard-Pyle, H. Braunstein and famous discounter Wilmington Dry Goods. Crosby & Hill dated from 1878 and operated its department store at Sixth and Market Streets. It abruptly closed its doors due to “financial strain” in March 1960. Kennard’s was one of Delaware’s oldest retailers and was founded in 1846. Headquartered at Seventh and Market Streets, Kennard’s eventually became a chain of six department stores. Its last store, the flagship store on the Market Street Mall, closed in March 1986. Braunstein’s, Delaware’s Fashion Capital, opened its Market Street store in 1917. It opened branches in locations such as Price’s Corner, Dover and Rehoboth Beach and eventually ceased operations in 1985. The Dry Goods was a popular, no-frills retailer that was founded on Market Street in 1924. The store began adding suburban Wilmington stores but the antiquated Wilmington flagship store was shut in 1974. The rest of the company grew to eight locations throughout the Delaware Valley until most stores were sold to Value City in May 1989.

In September 1947, Wanamaker’s unveiled architectural plans for its first branch store. Located on the Augustine Cut-Off, Wanamaker’s Wilmington was to be an eighty-thousand-square-foot building with a “country club atmosphere.” The store planned to open in 1950 and would be located in a mostly suburban area. Wanamaker’s searched for other sites closer to the inner-city Wilmington core but it chose this noncommercial address. Built of fieldstone and white brick, the store would be “surrounded by broad lawns, formal gardens, terraced walks, and have two parking areas concealed from public view by landscaping.”49 After the company completed a house-to-house survey of the Wilmington area, Wanamaker’s decided to double the size of the store in order to meet the potential demand.

On November 15, 1950, the $6 million Wanamaker’s Wilmington store opened its doors. Five hundred employees helped serve the thirty thousand people that came to shop at the store. The local newspaper spoke of the famous Wanamaker’s traditions that were carried through to the Wilmington location.

The graceful Wilmington, Delaware, John Wanamaker store, pictured here in 1991. Courtesy of the author.

Trucks deliver merchandise in preparation of the Wilmington store’s opening in November 1950. Courtesy of Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The Wanamaker eagle and organ, familiar to thousands of Delawareans who have shopped in the Philadelphia store, will be part of the fixtures of the new retail outlet. They are located on a platform midway between the first and second floors, just off the main stairway at the front of the store. Chairs have been furnished so that shoppers who tell their friends to meet them “at the eagle” will be able to wait in comfort. The chairs and mezzanine have been decorated with flowers for the opening.50

Customers were able to enjoy “superb food in quiet, relaxed, pleasant surroundings” in the store’s Ivy Tea Room.

The Wanamaker’s Wilmington store was very successful. Wanamaker family member Christopher Kellogg recalls that there was a different merchandise mix in Wilmington than in the other stores. “Wilmington had some funny quirks about it. I remember that Wilmington carried a quilted jacket for women. They were disgusting looking things that gave you no figure and made you look 20 pounds heavier. There were things that sold in the Wilmington store and nowhere else,” says Kellogg. CBS3 news anchor Pat Ciarrocchi grew up in Kennett Square and spent her youth shopping at Wanamaker’s in Wilmington.

A rare view of the Wilmington organ and Eagle. Courtesy of Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

I was always attached to the Wanamaker’s store in Wilmington. I could get there with my eyes closed. I can see it with the curved shape and the guy in the window playing the organ. As a kid, I would stand on the balcony and listen to the organ. I remember standing there for the concerts at Christmas. It was always so much fun because that organ had a great sound.51

Ciarrocchi continues to say “if you were to go shopping for school clothes, if you were to go get a special gift, if you were to go have a really great afternoon and have lunch with your mom, you went to Wanamaker’s.”

After Wanamaker’s settled in with their new Wilmington store, the company turned its attention to the New York operation. By the 1950s, the New York store was no longer making any money. “It didn’t know the New York market,” says Kellogg. The New York Wanamaker’s was seen as a very provincial store but was still respected among New York shoppers. Former Philadelphia newscaster Trudy Haynes grew up in Harlem and would go to the New York Wanamaker’s with her aunt.

It was an outing to go to Wanamaker’s. You had to get dressed up. The store had crystal chandeliers and had music floating through the store. It was very soft spoken. It was a very elegant store. We would just float through the store, not that we could afford to shop there.52

Part of the problem with the New York store was its size. “The store was just too big and it had too much merchandise and too much space. It was like two of the Philadelphia stores and it went across the street. It just went on and on,” says Louise Wanamaker.53 In 1951, the company began the process of pulling out of the old A.T. Stewart building and consolidating all business into the South Building dating from 1907. President John E. Raasch defended the consolidation and insisted there were no plans to pull Wanamaker’s out of its downtown location. He said the store was located in an excellent shopping area that was being supported by new housing.

The exterior of the Great Neck, Long Island, Wanamaker’s store from December 1951. Courtesy of the Gottscho-Schleisner Collection of the Library of Congress.

The grand staircase at the Great Neck Wanamaker’s store. The signature Wanamaker Eagle can be seen in the upper left corner. Courtesy of the Gottscho-Schleisner Collection of the Library of Congress.

Wanamaker’s was eager to assure New York shoppers that it was committed to the New York metropolitan area. The company chose a plot of land in Westchester County as a site for another suburban New York store and it opened its Great Neck, Long Island, branch location on May 16, 1951. The Wanamaker’s Great Neck store contained 45,200 square feet; it was roughly one-third of the size of the Wilmington Wanamaker’s. The store was too small and quickly proved to have inadequate selection for shoppers. “I was at Great Neck for the opening but I wasn’t there for the closing, which took place shortly afterwards,” says Christopher Kellogg. “It never worked to begin with. It was a bad location.”54

Richard C. Bond became president of Wanamaker’s in 1952 and was charged with fixing many of Wanamaker’s problems. He stressed the need for Wanamaker’s to be more proactive in suburban growth. One of Bond’s first big decisions was to move the Philadelphia Men’s Store back into the Main Store. The Lincoln-Liberty Building, home of the Men’s Store, was sold to Philadelphia National Bank. PNB intended to convert the building into its new headquarters. The Men’s Store moved to the second floor of the Chestnut Street side of the Wanamaker building. Actor and singer Danny Kaye opened the new Men’s Store on March 2, 1954, and the store proudly advertised that it had “the largest stock of men’s furnishings in the history of Wanamakers.”

The New York Wanamaker’s continued to be a drain on the company, and the headquarters in Philadelphia grew impatient with its performance. “The Philadelphia Board of Directors didn’t care for the New York store. They didn’t like New York in general,” says Christopher Kellogg. The New York store had a ninety-nine-year lease, and the Wanamaker Trustees saw that lease as “an albatross around their neck.” The employees’ union took a more active role in the New York store, which increased tensions with the Philadelphia headquarters.

On October 25, 1954, Wanamaker’s announced that the New York store would close its doors. The company said that its future was in the suburbs and vowed to keep the Great Neck store open. Wanamaker’s also said that they remained committed to the new Yonkers branch, then under construction. The Liberty Street store would also remain open to serve New York customers. Local 9 called the decision “hasty” and noted that eighteen hundred employees would lose their jobs. Campaigns were launched to save the store and Local 9 took charge. In a letter to employees dated November 5, 1954, Local 9 encouraged everyone to “pull together and save that grand old store worth one of the finest names in retailing. In union there is strength—united strength to build, not to liquidate.”55

The Wynnewood Wanamaker’s store as seen in July 1995. Courtesy of the author.

In the meantime, Wanamaker’s opened its third branch on November 15, 1954, in the Main Line Philadelphia community of Wynnewood. Along with Bonwit Teller, the 163,000-square-foot store helped anchor a shopping center. The Wynnewood Wanamaker’s was a success from the start. “It was a great little store,” says Kellogg. The success of Wynnewood helped offset the troubles with the New York store closure.

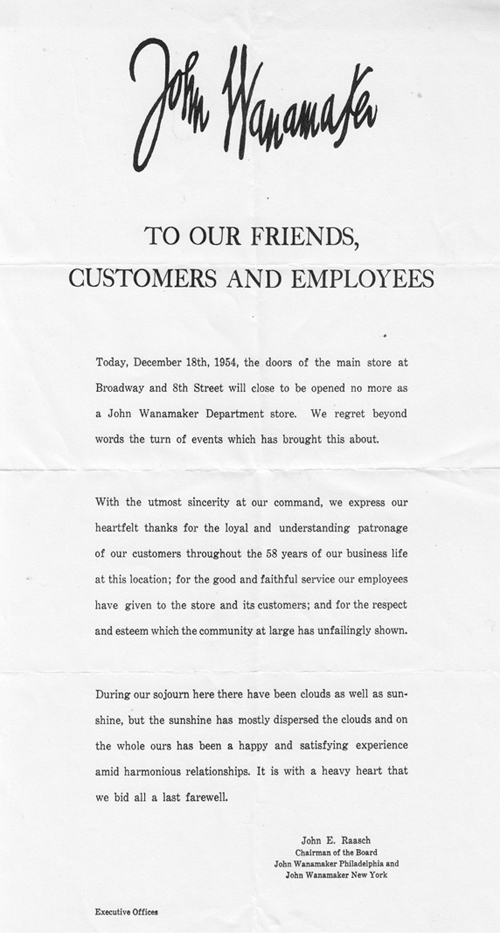

On December 18, 1954, the New York Wanamaker’s ended its run after fifty-eight years. The once quiet and elegant store was the scene of last-minute bargain hunting. It was an undignified ending for a noble store. Employees expressed shock and sadness about the store’s final hours.

One employee told a newspaper reporter:

You’d be amazed at how many people come up to me and say how sorry they are. People who came here for years, not just to buy, but to see their friends. These are the real John Wanamaker customers. The others—the ones who’ve showed up today and yesterday, like going to a funeral—they crawled out from under some rock.56

That same day, the Wanamaker Board of Directors received a letter from furrier Victor Asselin. He attacked the company for closing the store. “For a store with the name of Wanamaker to admit failure in New York is beyond comprehension. If any of you get more than a dollar a year, you are grossly overpaid. All you had to do was move!” said Asselin.57

Wanamaker’s also reversed its future plans for the small Great Neck store. In April 1955, the store’s lease was sold to Stern’s and a liquidation sale began. On May 5, 1955, the 112 employees of the Great Neck store lost their jobs.

Even before it opened, Wanamaker’s tried to sell the lease of its Yonkers branch to Macy’s but an acceptable deal with the shopping center’s landlord could not be reached. The company’s plans went forward and on April 28, 1955, the Cross County Shopping Center store in Yonkers, New York, opened for business. The store proved to be successful and it anchored the center with Gimbels. Wanamaker’s merchandise was a higher level than Gimbels’s but it wasn’t as expensive as Lord & Taylor and B. Altman. The store, and its merchandise, was perfect for Westchester County.

A letter to the New York Wanamaker’s employees and customers on the day of its closing on December 18, 1954. Courtesy of the author.

The entrance to the Yonkers Wanamaker’s store at the Cross County Shopping Center. This photograph was taken in April 1956. Courtesy of the Gottscho-Schleisner Collection of the Library of Congress.

The Yonkers Wanamaker’s was very profitable. Part of the success was due to its location just outside the city limits, thus making it outside the taxing zone. “It was a place where people went to save on their sales tax,” says Christopher Kellogg. For decades to come, it was Wanamaker’s sole department store operation in the New York metropolitan area.

On July 15, 1956, a five-alarm fire broke out at the old A.T. Stewart building at the former New York Wanamaker site. Six hundred firemen battled the city’s worst fire in twenty-one years. During the fire, the Lexington Avenue subway filled with water and the roof of the Astor Place subway station was reported “unsteady and vibrating.” The street around the store was in danger of collapsing. The following day, Meyer Berger wrote a column in the New York Times commenting on the old Wanamaker’s and the fire that devastated the building.

An interior view of the Yonkers John Wanamaker store. The photograph was taken in January 1995. Courtesy of the author.

Its soft spoken salespeople, its suave—but not too suave floorwalkers, its mellow indoor bells, the concerts in the great Wanamaker Auditorium, the air of quiet gentility that always lay, sort of reverent and hustled, over its well-stocked counters. Now it is suddenly gone.58