I was very taken with such things as the organ and the Christmas show and the feeling that people had for Wanamaker’s. But it turned out that it was more difficult to have it translate into “I’m going to shop there.”

—Richard P. Hauser, former president, Wanamaker’s

Carter Hawley Hale’s purchase of Wanamaker’s ended local control of the retail business. It ended the control by the seven-member board of trustees. The company lost business to stores like Bamberger’s and Strawbridge’s, and its stores desperately needed upgrading. Even Gimbels, with its new glitzy store in Center City, began to make a dent in its sales figures.

Carter Hawley Hale’s first order of business was to upgrade the stores. The company prepared to spend $30 million over the next five years on renovations. “Everyone at Carter Hawley Hale knew that there had not been a lot of capital spent on the stores up to date and it was something we were going to have to do,” says former president Richard P. Hauser. At the time, company officials stated, “In five years, we want to make it the best department store chain in the area.”86 Wanamaker’s decided to concentrate its initial improvement efforts on the Center City store.

By the early 1980s, more out-of-town department stores took root in Philadelphia. Bloomingdales and Abraham and Straus opened stores in new retail centers in King of Prussia and Willow Grove. Even B. Altman added a second Philadelphia area store in Willow Grove. The major retailers from New York that came to Philadelphia seemed better at retailing than either Wanamaker’s or Strawbridge & Clothier. Former president Richard P. Hauser says “my effort was to bring Wanamaker’s into the late twentieth century. It was hard to do because the customers were entranced by Bamberger’s, Saks Fifth Avenue, Bloomingdale’s and Lord & Taylor.” Wanamaker’s was not a money-maker when Hauser arrived. It was profitable but “it was not up to the standards that a good retail company expected.” When he arrived, Hauser was puzzled that Wanamaker’s did not seem to have its branch stores in the destination malls. “I wondered why Strawbridge branches were in better malls than Wanamaker branches,” says Hauser. “I was told that Wanamaker’s didn’t want to be in the same malls as Strawbridge & Clothier. We ended up in secondary malls, which made it very difficult.”87

Waiting at the Eagle in May 1978. Courtesy of the Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The Munkacsy paintings continued to be displayed during Lent 1979. Courtesy of the Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Wanamaker’s began upgrading the merchandise offerings, especially in the Center City store. The Tribout shop, the store’s elegant salon, received a full makeover. “The Tribout Shop didn’t have any rivals in the Philadelphia area,” says Professor Mercia Grassi. “Nan Duskin was its closest competitor.” Wanamaker’s also began to promote new in-store designer salons, featuring names such as Cartier and Gucci. Even as the store introduced higher end merchandise, Wanamaker’s continued to offer its traditional line of Rittenhouse Sportswear and Wanalyn dresses and coats.

Wanamaker’s signature Tribout Shop in 1981. Courtesy of the author.

Last-minute shopping at the Center City Wanamaker’s on Christmas Eve 1981. Courtesy of the Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The Crystal Tea Room, Wanamaker’s signature dining room, began to serve new food selections, from frittatas to snow pea pods at the restaurant’s salad buffet. But it continued to serve tea sandwiches to “ubiquitous, frosty haired ladies” that made lunch at Wanamaker’s a daily, social ritual. In a 1982 interview, Wanamaker’s vice president of food services, John O’Donnell, said, “I think if I took tea sandwiches off the menu they’d hang me by Billy Penn’s hat.”88 Wanamaker’s could not afford to alienate its traditional customer. The restaurant turned an extremely modest profit. “It’s very difficult to make money at a restaurant that serves one meal a day and no booze,” says Richard P. Hauser. The store prided itself on its traditional Philadelphia merchant reputation, and the Crystal Tea Room was one of Wanamaker’s many signature traditions.

In March 1983, family member Francis Kellogg purchased the remaining 50 percent ownership of the New York Liberty Street Wanamaker’s from Carter Hawley Hale. Carter Hawley Hale never paid much attention to the store. Kellogg said that since the Liberty Street operation was so small compared with the other Wanamaker’s branches, Carter Hawley Hale management referred to it as a “twig” in the sixteen-store chain.89 After he purchased Carter Hawley Hale’s 50 percent ownership, Kellogg was allowed to still call the store John Wanamaker Liberty Street. Within a few months, however, a rent increase made it impossible for the business to continue. Kellogg began to liquidate the Liberty Street store in August 1983. The move terminated one hundred jobs and ended almost eighty years of trade for the Wanamaker name in Manhattan.

A view of the Crystal Room in 1981. Courtesy of the Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Down Market Street, the privately held Strawbridge & Clothier battled a hostile takeover attempt. Members of the Strawbridge and Clothier families were the stockholders of the business. In 1983, New York investor Ronald Baron courted one Strawbridge family member’s stock interest. Over the next few years, Baron tried to acquire Strawbridge & Clothier while devoted family members urged their relatives not to sell. Baron never gained control of Strawbridge’s but it tested the loyalty of one of America’s last family-run department stores.

Strawbridge & Clothier became Philadelphia’s leading department store while Wanamaker’s desperately tried to find its footing. Hauser upgraded the store’s merchandise and image but it happened too quickly for its loyal shoppers and employees.

An article in the April 1989 issue of Philadelphia Magazine stated:

The message meant trouble from the tradition-bound staff, especially the buyers and merchandisers who didn’t like to be told what to do. Like most old-time department stores, Wanamakers had always been a middle-of-the-road kind of place—never so declasse as to scare away the carriage trade. For more than a century, Wanamakers had made its money, and its reputation, by being everything to everyone.90

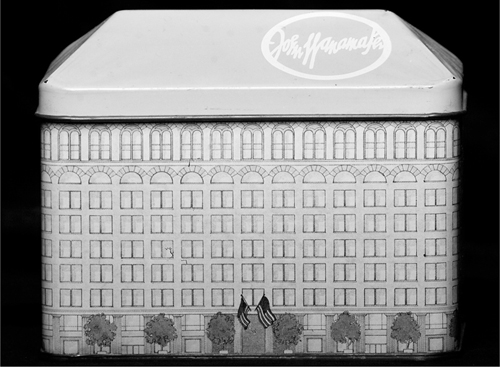

A souvenir tin of the John Wanamaker Center City store from 1986. Photo by Christian Colberg. Courtesy of the author.

Turning Wanamaker’s around proved more difficult than Carter Hawley Hale originally thought. The upper management of Carter Hawley Hale grew frustrated with Wanamaker’s. The stores urgently needed renovations. The merchandise mix confused the customers, and its market share continued to slide.

Like Strawbridge & Clothier, Carter Hawley Hale was the victim of a hostile takeover attempt. Owners of the Limited tried to purchase large quantities of Carter Hawley Hale’s undervalued stock. Carter Hawley Hale was a publicly traded company and attempts were made to block the sale. Carter Hawley Hale tried to raise the value of its stock. The company consolidated many of the operational functions at each of its divisions. Professor Mercia Grassi says, “In order to save money, they began central buying. But Carter Hawley Hale had no idea what the East Coast’s customers wanted.” Cutting costs at Carter Hawley Hale was simply not enough to raise the value of the company. Carter Hawley Hale had to shed some of its liabilities and the first place the company looked was Wanamaker’s. At the time, Carter Hawley Hale vice president for corporate affairs Bill Dombrowski said, “We did not need a division of the company that was not paying its way. The Limited made their offer and our world changed. Wanamakers was obviously going to require a lot more capital. And frankly, we didn’t have the capital.”91